The National Research Act and Belmont Report: A 50-Year Legacy of Ethical Research and Modern Challenges

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the National Research Act of 1974 and the ensuing Belmont Report, foundational pillars of modern research ethics.

The National Research Act and Belmont Report: A 50-Year Legacy of Ethical Research and Modern Challenges

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the National Research Act of 1974 and the ensuing Belmont Report, foundational pillars of modern research ethics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the historical context that prompted this legislation, details the three core ethical principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice, and explains their practical application through Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and the Common Rule. The article further examines contemporary challenges in the ethical oversight system, including gaps in privacy protection and conflicts of interest, and offers a forward-looking perspective on adapting this framework for emerging technologies like AI and gene therapy.

The Genesis of Modern Research Ethics: From Tuskegee to the National Research Act

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male at Tuskegee (1932-1972) stands as a seminal crisis in research ethics. This article analyzes the study's methodologies, the profound ethical failures inherent in its protocols, and the subsequent public outcry that directly catalyzed the creation of the National Research Act of 1974 and the Belmont Report. Framed within the context of modern research regulation, this analysis provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a historical framework for understanding the foundational principles of human subject protection—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—that underpin contemporary ethical research conduct.

The USPHS Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee was a 40-year observational study designed to document the natural progression of untreated syphilis in 399 African American men in Macon County, Alabama [1] [2]. A control group of 201 men without syphilis was also enrolled. The study was initiated in 1932, a time when effective treatments for syphilis were limited and toxic; however, the research continued for decades after penicillin became the standard, curative treatment for the disease in 1947 [3] [2]. The study was justified by its investigators based on a prior retrospective study of untreated syphilis in white males conducted in Oslo, Norway, with the explicit aim of comparing the pathological manifestations of the disease between racial groups [2] [4]. The prevailing, and erroneous, medical belief at the time was that syphilis affected the cardiovascular system of Black people more frequently, while targeting the nervous system of white people [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The methodology employed in the Tuskegee Study was marked by systematic deception and the withholding of treatment, resulting in significant harm to its participants.

Participant Recruitment and Retention

Investigators recruited 600 impoverished African American sharecroppers through the promise of free medical care, a powerful incentive for a population with limited access to healthcare [3] [2]. The men were told they were being treated for "bad blood," a local colloquialism for various ailments including anemia and fatigue, but were never informed of their syphilis diagnosis [1] [2]. To ensure participation in painful and non-therapeutic diagnostic procedures like lumbar punctures (presented as "special free treatment"), researchers sent deceptive letters titled "Last Chance for Special Free Treatment" [2]. To secure the ultimate research data—autopsy results—investigators offered to cover burial expenses, a significant inducement within the local cultural context [4].

Withholding of Treatment and Deceptive Practices

The core protocol of the study was the intentional observation of untreated syphilis. Key methodological failures included:

- Placebo Administration: Participants were given disguised placebos, such as aspirin and mineral supplements, while being led to believe they were receiving therapeutic treatment [3] [2].

- Active Prevention of Treatment: When penicillin became widely available in the mid-1940s, researchers actively prevented participants from accessing treatment. During World War II, PHS researchers intervened to prevent the treatment of 256 study subjects who had been diagnosed with syphilis at military induction centers [2]. Later, PHS staff directed local physicians and mobile treatment units to deny therapy to the enrolled men [4].

- Withholding Information: Researchers never informed the participants that penicillin was a safe and effective cure for their disease [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Study Duration | 1932 - 1972 (40 years) [1] |

| Funding Agency | U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) [2] |

| Participant Cohort | 600 African American men (399 with latent syphilis, 201 without as controls) [1] [2] |

| Key Deception | Told they were being treated for "bad blood"; not informed of syphilis diagnosis [1] |

| Penicillin Withheld | From 1947, when it became standard treatment [3] |

| Documented Harm | 28 deaths directly from syphilis; 100 from related complications; 40 wives infected; 19 children with congenital syphilis [3] [2] |

| 1974 Settlement | $10 million out-of-court settlement to participants and heirs [1] |

Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Diagnostic Tools in the Tuskegee Study

| Item / Procedure | Stated or Implied Function to Participants | Actual Function in Study Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin & Mineral Supplements | Treatment for "bad blood" [3] | Placebo to maintain participant compliance without providing therapeutic benefit [3] [2] |

| Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap) | "Special free treatment" or "spinal shots" [4] | Diagnostic procedure to collect cerebrospinal fluid for neurosyphilis analysis; non-therapeutic [4] |

| Blood Tests | Part of free health care [1] | To monitor syphilis progression (e.g., Wassermann test) and maintain study data [1] |

| Burial Insurance | Benefit for participation [2] | Incentive to secure permission for autopsy to obtain pathological confirmation of disease progression [4] |

The Public Outcry and Study Termination

For decades, the study continued without significant internal challenge from the medical community, despite the publication of numerous articles detailing its findings [2]. The crisis was catalyzed by Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal disease investigator in San Francisco, who learned of the study in the mid-1960s [3]. After repeatedly raising ethical concerns with his superiors to no avail, Buxtun leaked information to a reporter, Jean Heller of the Associated Press [3]. Heller broke the story on July 25, 1972, triggering immediate and widespread public outrage [5] [4]. The subsequent media scrutiny and public condemnation forced the government to convene an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, which found the study to be ethically unjustified. The panel recommended its immediate termination, which occurred on November 16, 1972 [1] [2].

Catalyzing Regulatory Reform: The Path to the National Research Act and Belmont Report

The public outcry over Tuskegee directly led to concrete legislative and ethical actions aimed at preventing future abuses.

The National Research Act of 1974

In direct response to the Tuskegee revelations, the U.S. Congress passed the National Research Act (NRA) in 1974 [5]. This landmark legislation had three primary components:

- It established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [5].

- It mandated the creation of a comprehensive set of ethical guidelines for human subjects research.

- It formally required that all entities receiving federal grants for research involving human subjects must have an Institutional Review Board (IRB) to review and approve the research protocols [5].

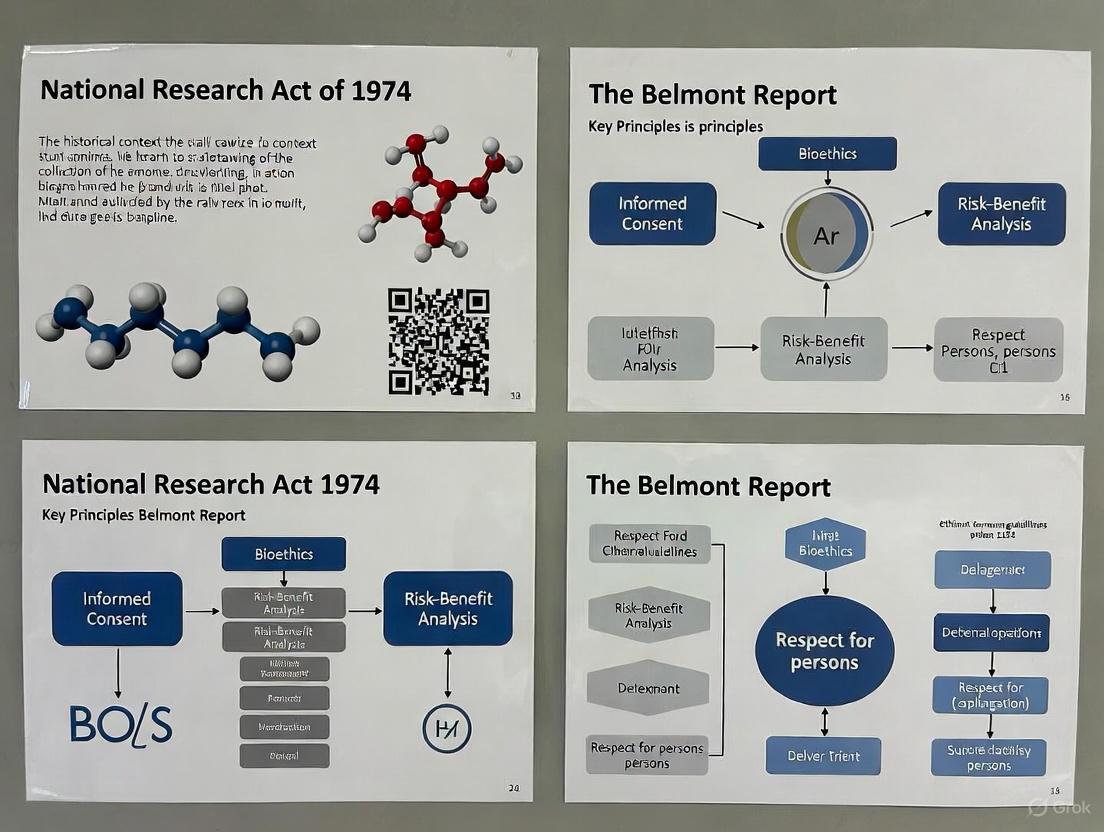

The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Applications

The National Commission, established by the NRA, produced the Belmont Report in 1979 [6]. This document identified three core ethical principles that should govern all research involving human subjects and provided a framework for their application [7]. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the ethical failures of Tuskegee, the principles established by the Belmont Report, and the resulting regulatory applications that define modern ethical research.

Table 3: The Core Ethical Principles of the Belmont Report and Their Applications

| Ethical Principle | Definition | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Recognition of the personal autonomy of individuals and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy [6] [7]. | Informed Consent: Subjects must be given all relevant information and voluntarily agree to participate without coercion [6]. |

| Beneficence | The obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [6] [7]. | Systematic Assessment of Risks and Benefits: The research must be justified by a favorable risk-benefit ratio, which is rigorously analyzed [6]. |

| Justice | The requirement for fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [6] [7]. | Equitable Selection of Subjects: No single group (e.g., based on race, class, etc.) should bear disproportionate risks or be unfairly excluded from benefits [6]. |

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study serves as a permanent cautionary tale about the perils of unregulated research and the ethical compromises that can occur when scientific inquiry is divorced from fundamental human rights. The public outcry it generated was not an endpoint but a catalyst, forcing a national reckoning that produced the National Research Act of 1974 and the ethical framework of the Belmont Report. For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this history is not merely academic. The principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice form the bedrock of the Common Rule regulations that govern their work daily, from IRB submissions and informed consent documents to the equitable design of clinical trials [5] [7]. Understanding this direct lineage from a profound ethical failure to a structured system of protection is essential for fostering a sustained culture of ethical vigilance and maintaining the fragile trust between the research community and the public it serves.

The National Research Act (NRA) of 1974 represents a foundational legislative response to serious ethical breaches in human subjects research that culminated in a remarkable bipartisan consensus. Enacted on July 12, 1974, by President Richard Nixon, this legislation emerged directly from congressional hearings directed by Senator Edward Kennedy that exposed egregious research abuses, most notably the Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee [8] [5]. The Tuskegee study, which persisted for four decades, involved monitoring 600 African-American men without their informed consent and deliberately withholding effective treatment even after penicillin became the standard cure [9] [10]. This scandal, publicized in 1972, created a political environment ripe for legislative action, leading to the creation of a comprehensive framework for protecting human research subjects [5] [9].

The legislative process demonstrated overwhelming bipartisan support. The bill (H.R. 7724) was introduced by Democratic Representative Paul G. Rogers of Florida and garnered 10 cosponsors from both political parties [11]. It passed the House on May 31, 1973, by an overwhelming 354-9 margin, and later passed the Senate on June 27, 1974, by a 72-14 vote, indicating strong cross-party consensus on the need for research ethics reform [8] [5]. This extraordinary bipartisan support ensured the Act's passage despite President Nixon's political preoccupation with the Watergate scandal during the same period [5].

Core Legislative Provisions and Mechanisms

The National Research Act established three primary mechanisms to protect human research subjects, creating a multi-tiered system of ethical guidance, institutional review, and federal regulation that continues to form the backbone of U.S. research protections.

Establishment of the National Commission

The Act created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, an expert body tasked with identifying "the basic ethical principles which should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects" [5]. The Commission was specifically directed to examine contentious issues including fetal research, psychosurgery, and protections for vulnerable populations such as children, prisoners, and institutionalized mentally ill persons [5]. Originally envisioned as a permanent entity, the Commission was authorized for less than three years as a legislative compromise but produced extraordinarily influential work products during its brief existence [5].

Institutional Review Board (IRB) System

The NRA formalized and expanded the existing model of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), requiring that all entities applying for federal grants involving human subjects research demonstrate they have established such boards to protect research participants' rights [8] [5]. This system leveraged local institutional knowledge while implementing federal standards, creating a decentralized but regulated oversight mechanism. According to a Government Accountability Office study cited in the search results, approximately 2,300 IRBs now operate in the United States, based at universities, healthcare institutions, and independent for-profit entities [5].

Regulatory Framework and Common Rule Foundation

The Act directed the Secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) to promulgate regulations governing human subjects research, leading to the establishment of Title 45, Part 46 of the Code of Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46) [8]. This regulatory foundation eventually evolved into the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects ("Common Rule"), formally adopted by 15 federal departments and agencies in 1991 [5] [10]. The Common Rule established consistent standards across most federal agencies conducting or funding human subjects research, creating the unified framework that researchers follow today [10].

Table 1: Key Legislative Components of the National Research Act

| Component | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| National Commission for Human Subject Protection | Identify ethical principles and develop guidelines for research conduct | Produced Belmont Report and specific reports on vulnerable populations |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) System | Local review of research protocols to protect participant rights | Required for all federally funded research; approximately 2,300 IRBs currently operating |

| Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46) | Establish legally binding requirements for human subjects research | Evolved into the "Common Rule" adopted by 15 federal agencies in 1991 |

The Belmont Report: Ethical Framework and Principles

The Commission's most enduring contribution, the Belmont Report, was published in 1979 and articulated three fundamental ethical principles that should govern research with human subjects: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice [6] [10]. These principles were developed through an extensive deliberative process that included consultation with philosophers Tom L. Beauchamp and James F. Childress, who would later expand these concepts in their landmark text Principles of Biomedical Ethics [12] [5]. The Commission initially identified seven ethical principles before distilling them to the three that would become the foundation for research ethics [5].

The principle of respect for persons recognizes the autonomy of individuals and requires that persons with diminished autonomy receive additional protections. This principle finds practical application in the requirement for informed consent, ensuring that potential research subjects receive adequate information, comprehend it, and volunteer participation without coercion [6] [10]. Beneficence requires that researchers maximize potential benefits while minimizing possible harms, implemented through systematic assessment of risks and benefits [6] [10]. Finally, justice addresses the fair distribution of research burdens and benefits across society, preventing exploitation of vulnerable populations and ensuring equitable selection of subjects [6] [10].

Table 2: Belmont Report Ethical Principles and Applications

| Ethical Principle | Definition | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Recognition of personal autonomy and protection for individuals with diminished autonomy | Informed consent process requiring information, comprehension, and voluntariness |

| Beneficence | Obligation to minimize potential harms and maximize benefits | Systematic assessment of risks and benefits in research design |

| Justice | Fair distribution of research burdens and benefits across society | Equitable selection of subjects to avoid exploiting vulnerable populations |

Implementation and Regulatory Evolution

The regulatory framework established by the National Research Act has evolved significantly since its initial implementation, with the Belmont Report serving as the ethical foundation for federal regulations governing human subjects research.

Development of the Common Rule

In 1981, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS, formerly DHEW) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued regulations based directly on the Belmont Report principles [10]. The DHHS promulgated 45 CFR Part 46 (Protection of Human Subjects), while the FDA issued 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56 governing human subjects protection and IRBs [10]. These parallel regulatory tracks established congruent but distinct requirements for federally funded research versus research involving FDA-regulated products.

A significant harmonization occurred in 1991 with the formal adoption of the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, known as the "Common Rule," by 17 federal departments and agencies [5] [10]. This created consistent standards across most federal entities conducting or sponsoring human subjects research, addressing previous fragmentation in regulatory requirements. The Common Rule established standardized procedures for IRB composition and function, informed consent documentation, and additional protections for vulnerable populations including pregnant women, prisoners, and children [10].

Modernization and Contemporary Challenges

Recent revisions to the Common Rule have attempted to address emerging challenges in research ethics, including the mandate for single IRB review for multi-site research to eliminate duplicative reviews and expedite the approval process [5]. However, significant limitations persist in the current regulatory framework. The Common Rule's exclusion of deidentified information and biospecimens from protection has become increasingly problematic as advanced reidentification technologies emerge [5]. Additionally, the regulation explicitly prohibits IRBs from considering "possible long-range effects of applying knowledge gained in the research" or broader societal implications, focusing solely on direct effects on research participants [5].

Impact on Research Practice and Protocol Development

Institutional Review Board Operations

The NRA's establishment of the local IRB model fundamentally reshaped research implementation, creating standardized procedures for protocol review and approval. IRBs must have at least five members with varying expertise, including scientific and non-scientific representatives, and must include at least one member not affiliated with the institution [5]. The review process evaluates studies based on specific criteria including risk minimization, reasonable risk-benefit ratio, equitable subject selection, informed consent documentation, data monitoring provisions, and privacy protections [5].

Quality assessment and improvement mechanisms for IRBs have evolved through organizations like Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research (PRIM&R), founded in 1974, which provides educational services and certification for IRB professionals [5]. The Association for Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs (AAHRPP), established in 2013, offers voluntary accreditation that approximately 60% of U.S. research-intensive institutions have pursued [5]. Federal oversight occurs through the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) and FDA inspections, though only a small fraction of IRBs undergo formal inspection annually [5].

The Researcher's Compliance Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Components for Human Subjects Research Compliance

| Component | Function | Regulatory Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Documentation | Detailed research plan describing objectives, methodology, and protection measures | 45 CFR 46.111; 21 CFR 56.111 |

| Informed Consent Forms | Documents ensuring subjects receive required information in comprehensible format | 45 CFR 46.116; 21 CFR 50.25 |

| IRB Approval Documentation | Formal certification of institutional review and approval | 45 CFR 46.109; 21 CFR 56.109 |

| Vulnerable Population Safeguards | Additional protections for children, prisoners, pregnant women | 45 CFR 46 Subparts B, C, D |

| Conflict of Interest Management | Procedures to identify and mitigate financial and professional conflicts | Institutional policies implementing PHS regulations |

| Data Safety Monitoring Plan | Procedures for ongoing risk-benefit assessment during research | 45 CFR 46.111(a)(6); NIH policy |

Critical Analysis and Contemporary Relevance

Enduring Strengths and Identified Limitations

The National Research Act's framework has demonstrated remarkable durability over five decades, with the Belmont Report's principles maintaining their central position in research ethics education and practice [12] [5]. The localized IRB review system has allowed context-specific ethical analysis while maintaining federal standards, and the Common Rule's harmonization created consistency across most federal research agencies [5].

However, significant limitations have emerged. The framework primarily applies only to federally funded research, creating protection gaps for privately funded studies unless institutions voluntarily apply Common Rule standards [5]. The IRB model faces inherent conflicts of interest, as institutional financial and professional interests in research approval may compete with participant protection mandates [5]. The proliferation of for-profit IRBs introduces additional concerns about potential conflicts when review decisions impact commercial relationships [5].

Future Directions and Modern Challenges

Contemporary research landscapes present challenges unanticipated in 1974, including genomic research, big data analytics, artificial intelligence applications, and innovative trial designs [5]. The absence of a standing national bioethics commission since 2017 creates a policy vacuum for addressing emerging issues like gene editing, xenotransplantation, and neurotechnology [5]. Sophisticated reidentification technologies undermine the regulatory distinction between identifiable and non-identifiable data, necessitating updated approaches to information privacy [5].

The single IRB mandate for multi-site research represents a significant operational shift aimed at efficiency but introduces new challenges regarding community engagement and local context integration [5]. International research collaborations highlight tensions between U.S. regulations and varying international standards, particularly regarding community oversight and societal implications consideration [5].

The National Research Act of 1974 represents a landmark bipartisan achievement that established America's foundational framework for research ethics oversight. Its creation emerged from specific ethical failures but resulted in a comprehensive system of ethical principles, institutional review mechanisms, and federal regulations that have guided research conduct for half a century. The enduring legacy of the NRA and its cornerstone Belmont Report continues to shape how researchers, institutions, and regulators balance scientific advancement with fundamental ethical obligations to research participants.

While the framework has demonstrated remarkable resilience, contemporary research environments present unprecedented challenges that will require ongoing refinement of these foundational principles. The continued relevance of this legislative achievement depends on maintaining its core ethical commitments while adapting its applications to evolving research paradigms, ensuring that the protection of human subjects remains paramount in the dynamic landscape of scientific investigation.

Historical Context and Legislative Origin

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was created by the National Research Act of 1974, signed into law by President Richard M. Nixon on July 12, 1974 [5] [13]. This legislative action was a direct response to public exposure of egregious ethical violations in research, most notably the U.S. Public Health Service's Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee [5] [14] [9]. The Tuskegee Study, which ran from 1932-1972, involved monitoring 600 African-American men with syphilis without informing them of their diagnosis and deliberately denying them effective treatment even after penicillin became available [13] [14]. The subsequent political embarrassment and public outcry forced the government to confront systemic failures in research oversight [13] [9].

Congressional hearings following these disclosures revealed multiple research abuses, generating bipartisan support for regulatory intervention [5]. The National Research Act passed with veto-proof margins (72-14 in the Senate and 311-10 in the House) [5]. The Act established a comprehensive framework with three main elements: (1) creation of a national commission to develop ethical guidance; (2) formalization of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) model; and (3) establishment of federal research regulations applicable to researchers receiving federal funding [5]. The Commission was originally proposed as a permanent entity but was authorized for less than three years as part of a legislative compromise [5].

Commission Mandate and Scope

The National Commission was specifically tasked with identifying "the basic ethical principles which should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects" and developing guidelines to ensure research would be "conducted in accordance with such principles" [5] [15]. The Commission's mandate extended to several contentious research areas that remained significant ethical concerns, including [5]:

- Fetal research

- Psychosurgery

- Boundaries between medical research and medical practice

- Criteria for assessing risks and benefits for research participants

- Informed consent for research involving vulnerable populations: children, prisoners, and individuals in psychiatric institutions

The 11-member Commission brought together multidisciplinary experts who were extraordinarily productive during their limited tenure [5]. Their work products, particularly the Belmont Report, have proven to be highly influential despite the Commission's temporary status [5] [15]. The Commission's reports on research with children and prisoners figured prominently in subsequent federal regulations [5].

Development of the Belmont Report

Philosophical Foundations and Ethical Principles

The National Commission published the Belmont Report in 1979, naming it after the Belmont Conference Center where they drafted the document [16] [14]. In developing this foundational framework, the Commission worked in subcommittees and consulted with prominent bioethicists Tom L. Beauchamp and James F. Childress to identify principles that would reflect the shared values of a diverse population [5]. The Commission initially identified seven ethical principles, which were later refined to the three now-familiar principles [5]:

Respect for Persons: Incorporates at least two ethical convictions: individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [6] [16] [7]. This principle divides into two moral requirements: acknowledging autonomy and protecting those with diminished autonomy [16].

Beneficence: Extends beyond merely refraining from harm to an obligation to secure the well-being of research participants [16]. This principle finds expression in two complementary rules: (1) do not harm, and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [6] [16].

Justice: Addresses the fair distribution of research burdens and benefits [6] [16]. This principle requires that subjects be selected fairly and that no age, race, class, gender, or ethnicity should disproportionately bear the risks or reap the benefits of research [6] [17].

The Commission's approach became known as "common morality principlism" [5]. This framework was designed to provide an "analytical framework" for ethical analysis rather than a rigid checklist or formula [6].

Operationalization of Principles

The Belmont Report systematically connected each ethical principle to concrete research applications, creating a practical bridge between theory and practice [6]:

Table: Operationalization of Belmont Report Principles

| Ethical Principle | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Informed Consent | Information, Comprehension, Voluntariness [13] |

| Beneficence | Assessment of Risks and Benefits | Systematic analysis of risks and benefits [6] [13] |

| Justice | Selection of Subjects | Fair procedures and outcomes in subject selection [13] |

The Report cautioned that these principles could conflict in practice and would require careful balancing in specific research contexts [7]. For example, research involving children creates tension between respecting a child's dissent (Respect for Persons) and a parent's permission for potentially beneficial research (Beneficence) [7].

Regulatory Impact and Implementation

Transformation into Federal Regulations

The Belmont Report provided the ethical foundation for subsequent federal regulations governing human subjects research [6] [7]. In 1981, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued regulations based on the Belmont Report [13]. The DHHS issued the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 45 (public welfare), Part 46 (protection of human subjects), while the FDA issued CFR Title 21 (food and drugs), Parts 50 (protection of human subjects) and 56 (Institutional Review Boards) [13] [17].

A significant regulatory milestone occurred in 1991 when the core DHHS regulations (45 CFR Part 46, Subpart A) were formally adopted by 15 other federal departments and agencies as the "Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects," commonly known as the Common Rule [5] [13]. This harmonization created a unified regulatory framework for most federally conducted or funded research involving human subjects [13].

Institutional Review Board System

The National Research Act formalized and expanded the Institutional Review Board (IRB) system by mandating that entities applying for grants or contracts involving human subjects research demonstrate they had established an IRB to "protect the rights of the human subjects of such research" [5]. While many research institutions already had local IRBs by 1974, the Act made them a universal requirement for federally funded research [5]. According to a Government Accountability Office study cited in the search results, as of 2023 there were approximately 2,300 IRBs in the United States, most affiliated with universities or healthcare institutions, with a growing number of independent, primarily for-profit IRBs [5].

The diagram below illustrates the regulatory framework and oversight system established by the National Research Act and operationalized through the Belmont Report:

Assessment of Regulatory Impact

Assessments of the Belmont Report's actual effect on federal regulations are divided, even among its creators [12]. Some commissioners and staff philosophers recognized the report's significant influence on regulations, particularly for gene therapy clinical trials [12]. In contrast, others indicated the report was intended to provide only a general moral framework rather than specific regulatory guidance [12]. Contemporary analysis suggests that while the Belmont Report's principles did not affect the basic sections of federal regulations for ethical reviews that were made uniform in 1981, they are clearly reflected in regulations on gene therapy clinical trials and policies regarding public review of protocols [12].

Methodological Framework for Ethical Review

IRB Review Methodology

The Belmont Report outlines a systematic methodology that IRB members should use to determine whether research risks are justified by potential benefits [16]. This methodological approach requires that:

- Those conducting the review gather and assess information about all aspects of the research [16]

- Alternatives be considered systematically and in a non-arbitrary way [16]

- The assessment process be rigorous and evidence-based [16]

- Communication between the IRB and investigator be factual and precise rather than ambiguous [16]

This framework ensures that ethical review is not merely a procedural hurdle but a substantive evaluation of research protocols through the lens of established ethical principles [16].

Essential Documentation and Regulatory Tools

Table: Essential Research Ethics Documentation and Tools

| Document/Tool | Function | Regulatory Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Belmont Report | Provides foundational ethical principles (Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice) | National Research Act of 1974 [6] [7] |

| Informed Consent Documents | Ensures participants receive all relevant information and voluntarily consent | 45 CFR 46.116 [13] [17] |

| IRB Protocol Application | Systematically assesses risks/benefits, subject selection, and consent processes | 45 CFR 46.109 [17] |

| Common Rule (45 CFR 46) | Establishes uniform requirements for federally funded human subjects research | Adopted by 15 federal departments/agencies [13] |

| FDA Regulations (21 CFR 50, 56) | Provides protections for human subjects in research involving FDA-regulated products | Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [13] [17] |

Contemporary Challenges and Legacy

Fifty years after its establishment, the system created by the National Research Act faces ongoing challenges [5]. These include the limitation that IRB review and Common Rule compliance are mandatory only for federally funded research, creating a patchwork of voluntary compliance and state laws that may be inadequate for modern research environments [5]. Additional challenges include the exclusion of deidentified information and biospecimens from protection despite advancing reidentification technologies, and the Common Rule's prohibition on IRBs considering "possible long-range effects of applying knowledge gained in the research" [5].

The National Commission established a model of expert bioethics advisory bodies that has continued through subsequent presidential commissions, including the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1978-83), the National Bioethics Advisory Commission (1996-2001), the President's Council on Bioethics (2001-2009), and the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues (established in 2009) [15]. However, since 2017, there has not been a comparable standing body to address emerging bioethical issues [5].

The Belmont Report's principles have endured for nearly 50 years and continue to provide the fundamental ethical framework for human subjects research in the United States [5] [6]. The universal appeal of this principlist approach is illustrated by its prominent place in U.S. regulations and international research ethics, with continued reliance on these principles as valuable guideposts for research ethics analysis by researchers, bioethics scholars, and the public [5].

Operationalizing Ethics: Implementing Belmont through IRBs and the Common Rule

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the three ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—articulated in the 1979 Belmont Report. Framed within the context of the National Research Act of 1974, this guide examines the philosophical foundations, regulatory operationalization, and contemporary applications of these principles for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The document includes structured data presentations, experimental protocols, and visualizations to support the practical implementation of this ethical framework in biomedical and behavioral research. By deconstructing these pillars, we aim to equip research professionals with the analytical tools necessary to navigate complex ethical landscapes in modern scientific inquiry.

Historical Context and Legislative Foundation

The National Research Act of 1974 (Public Law 93-348) was a direct legislative response to public disclosure of egregious ethical violations in human subjects research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [5] [18]. This study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service, tracked the natural progression of untreated syphilis in African American men without their informed consent and continued even after effective treatment with penicillin became available. The Act established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [12] [6], which was charged with identifying the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of human subjects research.

The Commission's deliberations culminated in the Belmont Report, published in 1979 [16]. The report derived its name from the Belmont Conference Center where the commission met to draft the document. The Belmont Report's primary achievement was the articulation of three fundamental ethical principles: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [16] [7]. These principles were intended to provide an "analytical framework" to guide researchers, institutional review boards (IRBs), and policymakers in resolving ethical problems arising from research with human subjects [6]. The framework was subsequently codified into federal regulations through the Common Rule (45 CFR 46) in 1991, which was adopted by 15 federal departments and agencies and continues to provide the regulatory foundation for human subjects protections in the United States [5] [19].

Table 1: Historical Progression of Human Subjects Protections

| Year | Document/Event | Primary Ethical Contribution | Limitations Addressed by Belmont Report |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code | Established requirement for voluntary consent | Focused primarily on autonomy; limited application to vulnerable populations [12] |

| 1964 | Declaration of Helsinki | Distinguished therapeutic vs. non-therapeutic research; emphasized beneficence [12] | Framework for protecting socially vulnerable groups remained vague [12] |

| 1974 | National Research Act | Created National Commission; mandated IRB review [5] [6] | Responded to specific abuses without comprehensive ethical framework [5] |

| 1979 | Belmont Report | Articulated three principles: Respect, Beneficence, Justice [16] | Provided systematic framework applicable to all research contexts [6] |

| 1991 | Common Rule | Codified Belmont principles into federal regulations [19] | Created uniform standards across federal agencies [19] |

The Ethical Framework: Principles and Applications

Principle 1: Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two distinct ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to additional protections [16]. This principle acknowledges the right of self-determining individuals to make their own decisions and live by their own choices, while simultaneously recognizing that not all individuals possess the capacity for full self-determination due to age, illness, disability, or other circumstances that restrict liberty [16] [7].

The primary application of Respect for Persons occurs through the process of informed consent, which the Belmont Report breaks down into three fundamental elements [18]:

- Information: Prospective subjects must be provided with all relevant information about the research, including procedures, purposes, risks, benefits, and alternatives. The Belmont Report makes specific recommendations about the information that should be conveyed, including the research procedure, purposes, risks and anticipated benefits, alternative procedures, and an offer to answer questions and allow withdrawal at any time [16].

- Comprehension: The manner and context in which information is conveyed must ensure that prospective subjects adequately understand the provided information. The report emphasizes the responsibility of researchers to present information in understandable, non-technical language appropriate to the subject's capabilities [18].

- Voluntariness: Consent must be given voluntarily, free from coercion, undue influence, or other forms of constraint or manipulation. The research context itself can create implicit coercion, particularly when researchers are in positions of authority over potential subjects [16].

For persons with diminished autonomy, such as children, prisoners, individuals with cognitive impairments, or those in subordinate social positions, additional safeguards are necessary. The Belmont Report notes that the extent of protection should be commensurate with the risk of harm and likelihood of benefit, and that judgments about diminished autonomy should be periodically reevaluated [16].

Principle 2: Beneficence

The principle of Beneficence extends beyond the non-maleficence precept of "do no harm" to encompass an affirmative obligation to secure well-being for research participants [16] [20]. This principle is expressed through two complementary rules: (1) do not harm, and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [16]. In research ethics, beneficence requires researchers to design studies that not only avoid unnecessary risks but also actively promote the welfare of participants and society [16] [7].

The application of beneficence occurs primarily through the systematic assessment of risks and benefits [16]. This process requires:

- Identification of Risks: Researchers must thoroughly identify and document all possible physical, psychological, social, and economic risks associated with the research procedures. These include not only immediate harms but also long-term consequences and potential impacts on participants' social relationships and economic status.

- Assessment of Benefits: Researchers must similarly identify and document potential benefits to participants and to society in the form of new knowledge, improved therapies, or enhanced social welfare.

- Risk-Benefit Analysis: The IRB must determine whether the risks to subjects are justified by the anticipated benefits to the subjects and society, and whether the research design minimizes risks while maximizing benefits [16].

The Belmont Report outlines a methodological approach for IRBs to systematically gather and assess information about all aspects of the research and consider alternatives in a non-arbitrary way, aiming to make the assessment process more rigorous and communication between the IRB and investigator less ambiguous [16].

Principle 3: Justice

The principle of Justice addresses the equitable distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [16] [6]. This principle requires that the selection of research subjects be scrutinized to avoid systematically recruiting subjects simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or social, racial, sexual, or economic status [16]. The historical exploitation of vulnerable populations in research, such as prisoners, institutionalized children, and racial minorities, exemplifies violations of this principle [12] [5].

The application of justice occurs primarily through the selection of subjects [16]. Ethical subject selection requires that:

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria are based on scientific requirements directly related to the research problem rather than convenience, privilege, or vulnerability [16].

- Vulnerable Populations receive special protection to ensure they are not selected for research due to their easy availability or manipulability rather than scientific necessity [5].

- Research Benefits are distributed equitably, ensuring that populations that bear the risks of research are not excluded from its potential benefits [7].

The Belmont Report emphasizes that the principle of justice raises questions about social equity, particularly when research offers potential benefits that might not be equally available to all groups in society [6]. This has particular relevance for drug development professionals conducting clinical trials in international settings or with underserved populations.

Figure 1: Ethical Framework of the Belmont Report

Operationalizing the Principles: Regulatory Implementation

The ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report were operationalized through federal regulations, primarily the Common Rule (45 CFR 46) and FDA regulations (21 CFR 50 and 56) [19]. These regulations translate the abstract ethical principles into concrete requirements for research conduct, IRB review, and informed consent procedures.

Table 2: Regulatory Implementation of Belmont Principles

| Ethical Principle | Regulatory Requirement | IRB Review Criteria | Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Informed consent process and documentation [7] | Assurance that informed consent will be sought from each subject or legally authorized representative [5] | Signed consent forms; consent documentation waivers [21] |

| Beneficence | Risk-benefit assessment; minimization of risks [16] | Risks to subjects are minimized and reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits [16] | Research protocol; data safety monitoring plans; adverse event reports |

| Justice | Equitable selection of subjects [16] [7] | Selection of subjects is equitable based on research objectives [16] | Recruitment materials; inclusion/exclusion criteria documentation |

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) serves as the primary mechanism for implementing these principles at the local level [5]. The National Research Act formalized and expanded IRB reviews by mandating them for all federally conducted or funded research [5]. According to a Government Accountability Office study cited in the search results, as of 2023 there were approximately 2,300 IRBs in the United States, most affiliated with universities or healthcare institutions, though for-profit IRBs have seen significant growth [5].

The 2018 revisions to the Common Rule introduced several modifications to modernize human subjects protections, including [19]:

- No longer requiring continuing review for some minimal-risk research

- Requiring informed consent to incorporate "key information" at the beginning of the consent form

- Requiring a single IRB of record for multisite studies

Contemporary Applications and Challenges in Research

Application in Drug Development and Clinical Trials

The principles of the Belmont Report present particular challenges and considerations in clinical trials and drug development. The principle of justice requires careful consideration of inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure equitable access to investigational therapies while protecting vulnerable populations [20]. The principle of beneficence necessitates rigorous risk-benefit assessments, especially in early-phase trials where potential benefits may be uncertain [16].

Emergency research presents unique challenges to the principle of respect for persons, as potential subjects may be unable to provide informed consent due to their medical condition. FDA regulations provide a narrow exception to informed consent requirements for emergency research under strictly defined circumstances [21]. To utilize this exception, investigators must satisfy eight specific conditions, including that the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver, and that additional protections such as community consultation and public disclosure are implemented [21].

Ethical Challenges in Specific Research Contexts

Addiction Research

Research with drug-using populations illustrates the complex application of Belmont principles in context. Participants in addiction research often face multiple vulnerabilities, including poverty, comorbid health conditions, illegal behaviors, and psychological characteristics such as cravings and impulsivity [20]. These vulnerabilities create ethical challenges for which federal regulations do not provide easy answers.

A study examining moral principles that street drug users apply to research ethical dilemmas found that participants employed a wide range of contextually sensitive moral precepts, including respect, beneficence, justice, relationality, professional obligations, rules, and pragmatic self-interest [20]. This suggests that ethical decision-making in addiction research requires careful consideration of participant perspectives and values, aligning with the Belmont Report's recommendation that ethical principles be applied in a contextually sensitive manner [20].

Figure 2: Ethical Challenges in Addiction Research Contexts

Digital and Online Research

Emerging research methodologies, particularly online field experiments, present novel challenges for applying Belmont principles. The 2014 Facebook emotional contagion study highlighted tensions between the principle of beneficence (maximizing benefits while minimizing harms) and respect for persons (adequate informed consent) in digital environments [18]. The scale and nature of digital research often make traditional consent procedures impractical, requiring new approaches to implementing ethical principles.

Limitations and Contemporary Critiques

Despite its enduring influence, the Belmont Report and its regulatory implementations face several contemporary challenges:

- Regulatory Gaps: The Common Rule applies only to federally funded research, creating a patchwork of protections that may not cover all research participants [5].

- Societal Implications: The Common Rule explicitly prohibits IRBs from considering "possible long-range effects of applying knowledge gained in the research" in assessing research risks, limiting their ability to address broader societal implications [5].

- Evolving Technologies: Emerging research areas such as gene therapy, artificial intelligence, xenotransplants, and brain-computer interfaces raise ethical questions not fully addressed by the current framework [5] [19].

- Principles Conflict: The Belmont principles are not rank-ordered and often conflict in practice, requiring case-by-case balancing that can lead to inconsistent applications [7] [5].

Table 3: Research Ethics Reagent Solutions

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Framework | Belmont Report Principles [16] | Provides foundational ethical principles for research design and review | All human subjects research |

| Regulatory Guidance | Common Rule (45 CFR 46) [19]; FDA Regulations (21 CFR 50, 56) [21] | Details specific regulatory requirements for human subjects protection | Federally funded research; FDA-regulated clinical trials |

| Review Mechanisms | Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) [5] | Provides independent ethical review and oversight of research protocols | All human subjects research |

| Informed Consent | Consent forms; Comprehension assessments [16] | Ensures voluntary participation based on adequate understanding of research | All research involving direct interaction with subjects |

| Risk Assessment | Data Safety Monitoring Boards (DSMBs); Adverse event reporting systems | Monitors participant safety and research integrity during study conduct | Clinical trials, especially those involving significant risks |

| Educational Resources | CITI Training; PRIM&R Conferences [5] | Provides researcher education on ethical principles and regulatory requirements | Research institutions; investigator training |

The three pillars of the Belmont Report—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—continue to provide an essential framework for ethical decision-making in human subjects research nearly five decades after their formal articulation. While scientific methodologies and technological capabilities have advanced dramatically since 1979, these fundamental principles have demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability across diverse research contexts.

For contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding both the philosophical foundations and practical applications of these principles remains critical to conducting ethically sound science. The framework encourages ongoing ethical reflection rather than rote compliance, recognizing that ethical challenges often involve balancing competing principles in specific contexts. As new ethical dilemmas emerge in areas such as digital research, artificial intelligence, and genetic engineering, the Belmont principles provide a stable foundation upon which to build responsive ethical analyses and protections.

The continuing evolution of research ethics, including recent updates to the Common Rule and ongoing debates about single IRB review and centralized oversight, demonstrates the dynamic nature of ethical oversight in scientific research. By deconstructing these three pillars, research professionals can better navigate this evolving landscape while maintaining the fundamental ethical commitments that protect research participants and preserve public trust in science.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) system serves as the cornerstone of ethical oversight for human subjects research in the United States, operating within a framework established by pivotal historical events and foundational ethical principles. The modern IRB system emerged directly from the National Research Act of 1974, a legislative response to public outrage over ethical abuses in research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [22] [14]. This act created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which was charged with identifying the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of research involving human subjects [14].

The Commission's work culminated in the 1979 Belmont Report, which articulates three core ethical principles essential to the protection of human research participants [6] [22]. These principles provide the philosophical foundation for all subsequent federal regulations and IRB operations:

- Respect for Persons: This principle acknowledges the autonomy of individuals and requires that subjects with diminished autonomy, such as children or those with cognitive impairments, are entitled to additional protections. In practice, this principle is implemented through the informed consent process [6].

- Beneficence: This principle obligates researchers to maximize possible benefits and minimize potential harms to participants. It requires a systematic analysis of risks and benefits [6] [22].

- Justice: This principle requires the equitable distribution of both the burdens and benefits of research. It demands that no single population (based on race, class, gender, etc.) disproportionately bears the risks of research or is unfairly excluded from its potential benefits [6] [22].

The Belmont Report's principles are not merely abstract concepts but provide the "compass" for the application of federal regulations governing human subjects research [6]. The IRB system represents the practical institutionalization of these principles, creating a formal process to ensure that research protocols adhere to these ethical standards before and during their execution.

IRB Composition and Membership Requirements

The effectiveness of an Institutional Review Board hinges on its composition, which is carefully regulated to ensure diverse expertise and perspectives. Federal regulations mandate specific membership requirements designed to promote thorough and balanced review of research protocols [23] [24].

Regulatory Requirements for Membership

An IRB must have at least five voting members, with a composition structured to provide comprehensive review capabilities [22] [24]. The membership must include both scientific and non-scientific representatives to ensure that both the methodological rigor and the humanistic implications of research are adequately evaluated [23] [24]. Furthermore, each IRB must include at least one member who is not otherwise affiliated with the institution and who is not part of the immediate family of a person who is affiliated with the institution [24]. This "unaffiliated" member represents the perspective of the community and helps safeguard the rights and welfare of research participants from outside the institutional context [23].

The diversity of an IRB extends beyond these basic regulatory categories. As stated in Lehigh University's policy, the IRB "shall be sufficiently qualified through the experience, expertise, and diversity of its members, including race, gender, and cultural backgrounds and sensitivity to such issues as community attitudes, to promote respect for its advice and counsel in safeguarding the rights and welfare of human subjects" [24]. This commitment to diversity helps ensure that the IRB is sensitive to community attitudes and capable of reviewing research protocols with appropriate cultural competence.

Member Roles and Responsibilities

IRB members assume significant responsibilities in protecting human research participants. Their primary duty is to consistently apply the ethical principles of the Belmont Report and federal regulations governing human research protections [24]. Members are expected to maintain knowledge of current regulations and ethical standards through ongoing education and training [24].

Specific roles within the IRB structure include:

- IRB Co-Chairs: Typically faculty with previous committee experience, co-chairs are responsible for ensuring proper review, approval, and disapproval of research protocols. They manage the efficient conduct of IRB meetings and respond to member concerns [24].

- Alternate Members: These are formally appointed members who may substitute for primary members when necessary. The IRB's written procedures must describe the appointment and function of alternate members, and the IRB roster should identify which primary member each alternate may replace [23].

- Consultants: The IRB may invite individuals with special expertise to assist in reviewing issues beyond the committee's available knowledge. These consultants provide information but do not vote on protocols [23] [24].

Members with conflicts of interest are prohibited from participating in the initial or continuing review of projects in which they have a conflicting interest, except to provide information requested by the IRB [23] [24]. This safeguard helps maintain the integrity of the review process.

Table: Required Composition of an Institutional Review Board

| Member Type | Minimum Requirement | Role and Qualifications |

|---|---|---|

| Total Voting Members | At least 5 [22] [24] | Sufficiently qualified through experience and expertise to review research conducted by the institution [24] |

| Scientist Members | At least 1 [23] [24] | Possess knowledge in scientific areas (e.g., physicians, PhD scientists) to evaluate methodological rigor [23] |

| Non-Scientist Members | At least 1 [23] [24] | Primary concerns in non-scientific areas (e.g., ethics, law, philosophy) to assess societal and ethical implications [23] |

| Unaffiliated Members | At least 1 [23] [24] | Not otherwise affiliated with the institution; represents community perspectives and interests [23] [24] |

IRB Review Procedures and Approval Criteria

The IRB review process is a systematic evaluation designed to ensure that research protocols meet stringent ethical and regulatory standards before human subjects are enrolled. This process varies in intensity based on the level of risk the research presents to participants, with different procedures for exempt, expedited, and full board review [25].

Types of IRB Review

The level of IRB review required for a research protocol is determined by specific criteria related to the risk level and nature of the research:

Exempt Review: Applies to research activities involving no more than minimal risk that fall into one or more specific categories defined by federal regulations (45 CFR 46.104) [25]. Although called "exempt," these studies still require formal submission and determination by the IRB before research begins. Examples include research involving educational tests, surveys, interviews, or observation of public behavior. Studies receiving an exempt determination are not subject to continuing review but still require researchers to uphold ethical obligations to participants as articulated in the Belmont Report [25].

Expedited Review: Authorized for research involving no more than minimal risk that fits one of the categories published by the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) [25] [26]. Expedited review may also be used for minor changes to already approved research. This review is conducted by a designated experienced IRB reviewer rather than the full committee, though the reviewer may refer any submission to the full board if necessary [25]. Most studies qualifying for expedited review do not require annual continuing review [25].

Full Board Review: Required for research involving more than minimal risk, or that does not meet the criteria for exempt or expedited review [25]. The University of Michigan's HRPP notes that full board review may also be required for research involving vulnerable populations (particularly prisoners), sensitive topics, genetic analyses, or complex research designs requiring multiple experts for evaluation [25]. This review occurs at a convened meeting with a quorum of IRB members present [24].

IRB Approval Criteria

For research to receive IRB approval, it must satisfy specific regulatory criteria designed to protect research participants. According to federal regulations and institutional policies, the IRB must ensure that:

- Risks to subjects are minimized by using procedures consistent with sound research design that do not unnecessarily expose subjects to risk, and whenever appropriate, by using procedures already being performed on the subjects for diagnostic or treatment purposes [25].

- Risks are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result [25].

- Selection of subjects is equitable, taking into account the purposes of the research and the setting in which it will be conducted [25].

- Informed consent will be sought from each prospective subject or the subject's legally authorized representative, and will be appropriately documented [25].

- The research plan makes adequate provision for monitoring data collection to ensure the safety of subjects [25].

- Adequate provisions are made to protect the privacy of subjects and to maintain the confidentiality of data [25].

- Additional safeguards are included for subjects likely to be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence [25].

The review process includes evaluation of all study materials, including protocols, investigator credentials, informed consent documents, and recruitment materials [26]. The IRB has the authority to approve, require modifications to secure approval, or disapprove research [23].

Table: IRB Review Types and Characteristics

| Review Type | Risk Level | Reviewer | Common Examples | Typical Turnaround |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exempt Review [25] | No more than minimal risk | IRB Chair, expedited reviewers, or qualified staff [25] | Educational tests, surveys, interviews, observation of public behavior [25] | <1 week [25] |

| Expedited Review [25] [26] | No more than minimal risk | Experienced IRB member (expediting reviewer) [25] | Certain blood sampling, prospective data collection, voice/video recording [25] | 2-4 weeks [25] |

| Full Board Review [25] | More than minimal risk | Convened meeting of IRB members [25] | Clinical trials, research with vulnerable populations, genetic studies [25] | 4-8 weeks [25] |

IRB Review Determination Outcomes

Following review, the IRB may issue several types of determinations:

- Approved: The application is approved as submitted. The approval date is the date of the IRB review [25].

- Approved with Contingencies: The application is approved, contingent on submission of specified changes to the protocol, informed consent documents, and/or other supporting materials. Final approval is granted when the IRB has reviewed and approved all requested changes [25].

- Changes Requested (Expedited Review): Substantial changes to the application and/or materials are required before the expediting reviewer can approve the study [25].

- Action Deferred: The IRB needs additional information from the investigator before making all determinations necessary to approve the study [25].

- Disapproved: The protocol does not provide adequate protection to human participants, and it is unlikely that it can be modified to provide such protection. The IRB provides a statement of reasons for its decision [25].

IRB Review Process Workflow: This diagram illustrates the systematic pathway for IRB review, from initial submission through various review types to final determination.

Local IRB Operations and Single IRB Models

The implementation of IRB oversight occurs through both local institutional IRBs and, increasingly, through single IRB (sIRB) models for multi-site research. Understanding the operations and distinctions between these models is essential for contemporary research administration.

Local IRB Operations and Institutional Responsibilities

Local IRBs are typically established within academic institutions, medical centers, and other organizations that conduct human subjects research. While these IRBs apply the same regulatory criteria for approval as central IRBs, they have often expanded their roles to encompass broader institutional responsibilities [27]. These expanded functions may include:

- Ancillary reviews such as institutional biosafety committee (IBC) review, radiation safety review, and conflicts of interest (COI) reviews [27].

- Gatekeeping activities including review of contract language for participant protections [27].

- Ensuring institutional compliance with state and local laws, institutional policies, and specific requirements of funding agencies [28].

These additional responsibilities have resulted in comprehensive Human Research Protection Programs (HRPPs) that vary widely across institutions [27]. The local IRB operates as a central component of these broader protection programs, which work to ensure research is not initiated until all organizational requirements are met [27].

Single IRB (sIRB) Model for Multi-site Research

In response to inefficiencies and inconsistencies in multiple IRB reviews for the same multi-site study, U.S. federal agencies implemented policies requiring the use of a single IRB for domestic, federally funded, non-exempt multi-site research [28]. The Revised Common Rule [45 CFR 46.114(b)] Cooperative Research Policy and the National Institute of Health (NIH) Policy on the Use of a Single Institutional Review Board mandate this approach to streamline ethical review without compromising participant protections [28].

The sIRB model designates one IRB as the "IRB of record" for all participating sites, eliminating duplicative reviews while maintaining rigorous ethical oversight [28]. However, this model does not eliminate all local responsibilities. Each participating institution remains responsible for:

- Researcher training and qualifications [28]

- Conflict of interest disclosures and management [28]

- Compliance with HIPAA and other privacy regulations [28]

- Conducting ancillary reviews such as IBC or radiation safety [28]

- Ensuring compliant research conduct according to state and local laws [28]

The successful implementation of the sIRB model requires clear documentation of the arrangement, typically through a reliance agreement that formally outlines the division of responsibilities between the reviewing IRB and the relying institution [28].

Table: Comparison of Local IRB vs. Single IRB (sIRB) Models

| Aspect | Local IRB Model | Single IRB (sIRB) Model |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Review | Reviews research conducted primarily within a single institution [27] | Serves as IRB of record for multiple sites in a collaborative study [28] |

| Primary Advantage | Deep understanding of local context and institutional policies [27] | Streamlined process, consistent review, eliminated duplication for multi-site trials [28] |

| Institutional Responsibilities | Comprehensive: IRB review plus ancillary reviews, training, contract review [27] | Limited to non-IRB functions: local training, COI, ancillary reviews, state/local law compliance [28] |

| Regulatory Mandate | Traditional model for single-site research | Required for most federally-funded, domestic, non-exempt multi-site research [28] |

| Operational Impact | Manages all aspects of human research protections for institutional studies [27] | Requires coordination with central IRB and maintenance of local oversight responsibilities [28] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for IRB Submissions

Successful navigation of the IRB review process requires careful preparation and comprehensive documentation. Researchers must submit a complete application package that addresses both regulatory requirements and the ethical principles of the Belmont Report. The following components are essential for most IRB submissions.

Table: Essential Components for IRB Submissions and Protocol Development

| Component | Function and Purpose | Regulatory/Ethical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Research Protocol | Detailed study plan describing objectives, design, methodology, statistical considerations, and organization [25] | Systematic investigation designed to contribute to generalizable knowledge [25] |

| Informed Consent Documents | Provides prospective subjects with information needed to make voluntary decision about participation [23] [22] | Respect for Persons principle (Belmont Report) and FDA regulations 21 CFR 50.25 [23] [6] |

| Recruitment Materials | All advertisements, scripts, letters, and emails used to identify and enroll subjects [28] | Equitable selection of subjects (Justice principle) and minimization of coercive influence [6] |

| Data Collection Instruments | Surveys, interview guides, case report forms, and data abstraction tools [25] | Assessment of risks and benefits (Beneficence principle) and privacy protections [6] |

| Investigator CV/Biosketch | Documentation of researcher qualifications and training in human subjects protection [26] | FDA regulations 21 CFR 56.107 requiring scientifically qualified investigators [23] |

| Local Context Information | For sIRB review: information about local laws, facilities, and resources at performing sites [28] | OHRP requirement for sIRB to consider local context in review process [28] |

| Conflict of Interest Disclosures | Identification and management of financial or other interests that may affect research [28] | Institutional responsibility to ensure objectivity in research [28] |

Belmont Report to IRB Application: This diagram illustrates how the ethical principles established in the Belmont Report translate into specific IRB application components and review considerations.

The IRB system represents the practical implementation of ethical principles established in response to historical abuses in human subjects research. From its foundation in the National Research Act of 1974 and the ethical framework of the Belmont Report, the system has evolved to provide comprehensive oversight of research involving human participants [6] [22] [14]. The composition of IRBs, with mandated diversity of expertise and perspective, ensures that research protocols receive balanced review from both scientific and ethical standpoints [23] [24].

The contemporary IRB system continues to adapt to changing research paradigms, particularly with the implementation of the single IRB (sIRB) model for multi-site research [28]. While this model streamlines review processes, it maintains rigorous protection standards while recognizing that local institutions retain important responsibilities for researcher training, conflict of interest management, and compliance with local laws and policies [28].

For researchers, understanding the IRB system—its historical context, regulatory requirements, and operational procedures—is essential for designing ethically sound research and successfully navigating the review process. The system's ultimate goal remains the protection of human subjects while facilitating valuable research that contributes to generalizable knowledge, maintaining the delicate balance between scientific progress and ethical responsibility that was envisioned by the creators of the Belmont Report.

The Common Rule stands as the cornerstone of ethical standards for human subjects research in the United States. Formally known as the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, this regulation was established to create a uniform framework across federal departments and agencies following the ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report [29] [30]. The Belmont Report, a pivotal document developed in response to the National Research Act of 1974, established three fundamental ethical principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The Common Rule operationalizes these principles into specific regulatory requirements that govern the conduct of human subjects research today [29].

The term "Common Rule" refers specifically to U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) policy 45 CFR 46, which defines what constitutes "research" and "human subject" and codifies the ethical principles of the Belmont Report into administrative law [29]. What makes this policy "common" is that it has been adopted by 17 federal departments and agencies, creating consistent expectations for researchers and institutions regardless of which federal agency is supporting the research [31]. This harmonized approach ensures that human subjects receive the same fundamental protections across the federal government.

Core Regulatory Framework and Key Provisions

Scope and Definitions

The Common Rule applies to all research involving human subjects that is conducted or supported by any federal department or agency that has adopted the policy [32] [30]. Each agency publishes an identical version of the Common Rule in its own regulations, creating consistency while maintaining individual agency enforcement capabilities [33].

The regulations establish precise definitions for key terms:

Research: A systematic investigation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge [32]. This includes research development, testing, and evaluation.

Human Subject: A living individual about whom an investigator obtains (1) data through intervention or interaction with the individual, or (2) identifiable private information [32].

IRB (Institutional Review Board): A board formally designated by an institution to review, approve, and conduct periodic review of research involving human subjects, with the primary purpose of assuring the protection of human subjects' rights and welfare [32].

Exemptions and Excluded Activities

The Common Rule identifies categories of research that may be exempt from IRB review based on their minimal risk nature. The 2018 revisions expanded and clarified these categories to reduce unnecessary regulatory burden [34] [35]. Some activities are specifically identified as "not human research" and do not require IRB review, including:

- Scholarly and journalistic activities focusing directly on specific individuals

- Public health surveillance authorized by public health authorities

- Criminal justice activities for investigative purposes

- National security operational activities [35]

Table: Categories of Research Activities Not Requiring IRB Review Under the Common Rule

| Activity Category | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Scholarly Activities | Focus directly on specific individuals | Oral history, journalism, biography, literary criticism, legal research, historical scholarship |