The Belmont Report in Practice: A Guide to Ethical Principles for Research and Drug Development Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the three core ethical principles of the Belmont Report—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—and their critical application in contemporary biomedical and clinical research.

The Belmont Report in Practice: A Guide to Ethical Principles for Research and Drug Development Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the three core ethical principles of the Belmont Report—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—and their critical application in contemporary biomedical and clinical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the historical foundation of these principles, details their methodological implementation in study design and informed consent, addresses common challenges in balancing ethical obligations, and validates their enduring impact on modern regulations and gene therapy trials. The content is structured to equip professionals with a practical framework for navigating complex ethical dilemmas throughout the research lifecycle.

The Bedrock of Research Ethics: Understanding the Belmont Report's History and Core Principles

The Belmont Report, officially titled "Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research," stands as a cornerstone document governing ethical conduct in research involving human subjects. Published in 1979 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, this report emerged from a direct congressional mandate within the National Research Act of 1974 [1] [2]. This legislation was enacted largely in response to growing public outcry over ethical violations in research, most notably the Tuskegee Study, which revealed profound deficiencies in the protection of research participants [2]. The resulting ethical framework provides the foundational principles that continue to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in the design, review, and conduct of clinical research, ensuring that scientific advancement does not come at the cost of human rights or dignity.

Historical Backdrop: Pathway to Regulation

Pre-Belmont Ethical Codes and Their Limitations

Before the Belmont Report, several international codes attempted to establish ethical standards for human subjects research, but each had significant limitations. The Nuremberg Code, decreed in 1947 during the Doctors' Trial, established the absolute necessity of voluntary consent from competent human subjects free from coercion [3]. While it contained elements related to beneficence and justice, its primary focus was on autonomy, and it was drafted in reference to prisoners in concentration camps, limiting its broader applicability [3]. Subsequently, the Declaration of Helsinki, first adopted in 1964 by the World Medical Association (WMA), placed greater emphasis on the ethical principle of Beneficence and entrusted research ethics committees with approving research protocols [3]. A critical limitation of both documents was their inadequate consideration of protecting socially vulnerable groups such as children or adults with diminished decision-making capacity [3].

The Catalysts for U.S. Action and the National Research Act

In the United States, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW), now the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), began developing guidance and regulations to address the participation of vulnerable populations in research [3]. However, the pivotal moment came with public disclosure of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which African American men with syphilis were left untreated for decades without their knowledge to study the natural progression of the disease [2]. The ensuing scandal created immense political pressure, leading Congress to pass the National Research Act of 1974 [2]. This Act created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research and charged it with identifying comprehensive ethical principles for protecting human research subjects [3] [2]. The Commission, meeting at the Belmont Conference Center, developed the report that would carry its name.

Chronology of Key Events

Table 1: Timeline of Key Events Leading to the Belmont Report

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code | Established voluntary consent as essential, but context-limited [3]. |

| 1964 | 1st Declaration of Helsinki | Distinguished therapeutic/non-therapeutic research; emphasized beneficence [3]. |

| 1974 | National Research Act | Congressional response to ethical violations; created National Commission [2]. |

| 1979 | Belmont Report Published | Articulated three core ethical principles for human subjects research [1]. |

| Late 1970s-Early 1980s | Common Rule (45 CFR 46) | HHS codified regulations based on Belmont principles [1]. |

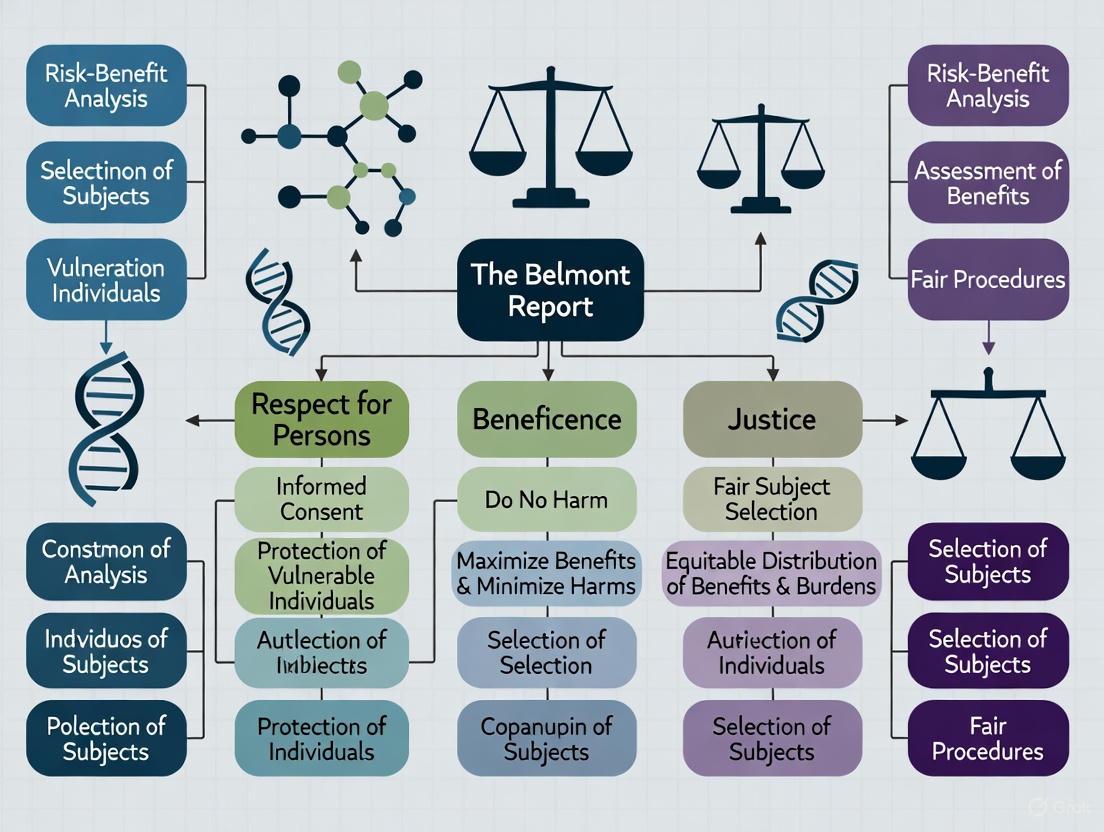

Figure 1: The Regulatory Pathway from Ethical Violations to Federal Rulemaking

Core Ethical Principles of the Belmont Report

The Belmont Report established three fundamental ethical principles that form the bedrock for the protection of human research subjects: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [1] [2]. These principles provide the moral foundation from which specific regulations and procedures are derived.

Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [1]. This principle acknowledges the right of self-determination for individuals capable of deliberating about their personal goals and acting under that direction. Simultaneously, it recognizes that not all individuals are capable of full self-determination due to illness, mental disability, or circumstances that severely restrict liberty [1].

The application of this principle leads to the requirement of informed consent in research. To respect autonomy, investigators must ensure subjects enter research voluntarily with adequate information and comprehension, and that they have the opportunity to ask questions and withdraw from the research at any time without penalty [1]. For populations with diminished autonomy—such as children, prisoners, or individuals with cognitive impairments—additional safeguards must be implemented, which may include exclusion from certain types of research or requiring permission from legally authorized representatives [1].

Beneficence

The principle of Beneficence extends beyond simply refraining from harm to encompass the ethical obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [1] [2]. This principle affirms that persons are treated in an ethical manner not only by respecting their decisions and protecting them from harm, but also by making active efforts to secure their well-being [1].

In practice, beneficence requires a systematic assessment of risks and benefits associated with the research [1] [2]. Investigators and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) must carefully analyze the nature and scope of risks, including physical, psychological, social, and economic harms, and weigh them against the anticipated benefits to the individual subject and/or the broader society [1]. The Belmont Report cautions that the presence of any research risk necessitates the existence of potential benefits, either to the subject or to society at large [1].

Justice

The principle of Justice requires the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [2]. This principle addresses the ethical concern that no single group in society should disproportionately bear the risks of participation in research while another group reaps the benefits [1] [2].

The application of justice in subject selection requires investigators to examine whether they are systematically selecting subjects simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or due to social, racial, sexual, or cultural biases [1]. Historically vulnerable populations, such as prisoners, institutionalized individuals, and economically disadvantaged persons, should not be targeted for risky research simply because they are accessible, nor should they be excluded from potentially beneficial research without sound scientific justification [1]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria should be based on those factors that most effectively and soundly address the research problem, not on convenience or social bias [1].

Table 2: The Three Ethical Principles and Their Practical Applications

| Ethical Principle | Core Meaning | Practical Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Recognition of personal autonomy and protection for those with diminished autonomy. | Informed consent process; additional protections for vulnerable populations. |

| Beneficence | Obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harms. | Systematic assessment of risks and benefits; favorable risk-benefit ratio. |

| Justice | Fairness in distribution of research burdens and benefits. | Equitable selection of research subjects; avoidance of exploiting vulnerable populations. |

The Belmont Report's Enduring Impact on Research Regulation

Influence on Federal Regulations and Institutional Review

The Belmont Report directly influenced the development and revision of federal regulations for human subjects protection, most notably the Common Rule (45 CFR 46), which established uniform policies across multiple federal agencies [1] [3]. The Report also provided the analytical framework for the Institutional Review Board (IRB) system, giving IRBs a structured method to determine whether the risks to research subjects are justified by the potential benefits [1]. According to this method, IRBs systematically gather and assess information about all aspects of proposed research, consider alternatives, and communicate their findings to investigators in a factual and precise manner [1].

Modern Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Research

The principles of the Belmont Report continue to guide contemporary research oversight and practice. Recent FDA guidance documents demonstrate how these ethical foundations evolve to address new challenges while maintaining their core commitments:

- Informed Consent and Respect for Persons: The FDA's 2025 draft guidance, "Evaluation of Sex-Specific and Gender-Specific Data in Medical Device Clinical Studies," encourages science-driven consideration of sex and gender to ensure medical devices are safe and effective for all potential users, reflecting the principle of justice and respect for personhood [4].

- Beneficence in Risk Assessment: The FDA's 2025 final guidance, "Action Levels for Lead in Processed Food Intended for Babies and Young Children," directly applies beneficence by establishing limits to reduce dietary exposure to contaminants in vulnerable populations [4].

- Justice in Subject Selection: Recent FDA initiatives, including the draft guidance "Diversity Action Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Populations in Clinical Studies," directly address the principle of justice by working to ensure clinical trial populations better represent the patients who will ultimately use medical products [4].

Ethical Framework for Emerging Research Technologies

The Belmont principles also provide guidance for navigating ethical challenges in cutting-edge research areas. For instance, the FDA and NIH have issued updated recommendations on human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps) that eliminate previous screening questions specific to men who have sex with men (MSM) and instead recommend assessing donor eligibility using the same individual risk-based questions for every donor, regardless of sex or gender [4]. This policy shift reflects an evolving application of the justice principle, reducing discrimination while maintaining safety.

Similarly, new policies regarding the security of human biospecimens and associated data, including restrictions on distribution to countries of concern, reflect contemporary applications of the beneficence principle by seeking to protect research participants and national interests in an increasingly complex global research environment [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Implementing Belmont Principles

Table 3: Essential Tools for Implementing Ethical Research Practices

| Tool/Component | Function in Ethical Research | Belmont Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent Document | Provides comprehensive information about the study in understandable language; ensures voluntary participation. | Respect for Persons |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocol | Detailed research plan submitted for ethical review, including rationale, methodology, and participant protections. | Beneficence, Justice |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment Matrix | Systematic tool for identifying, quantifying, and weighing potential harms against anticipated benefits. | Beneficence |

| Participant Recruitment Materials | Advertisements, brochures, and scripts designed to enroll subjects without coercion or undue influence. | Respect for Persons, Justice |

| Data Safety Monitoring Plan | Procedures for ongoing review of accumulated data to ensure participant safety and study validity. | Beneficence |

| Vulnerable Population Safeguards | Additional protections (e.g., assent procedures, legal representatives) for those with diminished autonomy. | Respect for Persons, Justice |

| Diversity and Inclusion Plan | Strategy to ensure equitable enrollment across demographic groups relevant to the research question. | Justice |

The journey From the National Research Act to the Belmont Report represents a pivotal transformation in the American research landscape, establishing an enduring ethical framework that continues to guide scientific inquiry. The three principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice provide more than historical guidance; they form a living analytical framework that adapts to new scientific challenges while maintaining fundamental protections for human dignity. For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this historical context and the profound ethical principles embedded in the Belmont Report remains essential for conducting scientifically valid and ethically sound research that advances knowledge while honoring our shared commitment to human rights.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the three foundational ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—as defined by the Belmont Report. Framed within the context of human subjects research regulation, this guide examines the historical imperatives, detailed applications, and ongoing relevance of these principles for contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The document synthesizes original regulatory text with modern interpretations to offer a comprehensive ethical framework supported by structured data tables, procedural workflows, and practical implementation tools designed to ensure rigorous protection of human research participants.

The Belmont Report was designed to identify basic ethical principles and develop guidelines that should govern research involving human subjects, thereby preventing such abuses [1]. It serves as the primary ethical foundation for the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (the "Common Rule") and is cited by institutions like the University of Wisconsin-Madison as the basis for protecting the rights and welfare of research subjects [1]. The report established three core principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—which form the essential pillars for the ethical conduct of research [6].

The Ethical Principles: Conceptual Foundations

Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [1]. This principle acknowledges the personal dignity and liberty of individuals, requiring that researchers acknowledge autonomy and protect those with reduced autonomy, such as children, individuals with cognitive disabilities, or prisoners [6]. The moral requirements here involve acknowledging autonomy and providing protection for the vulnerable.

Beneficence

The principle of Beneficence extends beyond merely refraining from harm to encompassing the obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize potential harms [1] [6]. This principle is often expressed in a two-part formulation: (1) do not harm, and (2) maximize possible benefits while minimizing possible harms [6]. In research practice, this requires a systematic assessment of risks and benefits to ensure the well-being of research subjects is secured.

Justice

The principle of Justice requires the fair distribution of both the burdens and benefits of research [1]. It addresses the ethical obligation to ensure that exploitative research is avoided and that the selection of research subjects is scrutinized to determine whether some classes are being systematically selected simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or social status rather than for reasons directly related to the research problem [6]. This principle guards against the exploitation of vulnerable populations.

Table 1: Core Ethical Principles of the Belmont Report

| Ethical Principle | Core Concept | Moral Imperative | Vulnerable Populations Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Individual autonomy and protection of those with diminished autonomy | Recognize voluntary, informed choice; provide special protection for diminished autonomy | Children, prisoners, individuals with cognitive or psychological impairments [6] |

| Beneficence | Obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harms | Do not harm; maximize possible benefits and minimize possible risks | Requires heightened assessment for all participants, with extra protections for vulnerable groups [6] |

| Justice | Fairness in distribution of research burdens and benefits | Ensure equitable selection of subjects; avoid exploitation of vulnerable populations | Ethnic and racial minorities, economically disadvantaged, the institutionalized [6] |

Practical Application: Translating Principles to Practice

The Belmont Report outlines how its ethical principles should be applied in research practice through three key areas: Informed Consent, Assessment of Risks and Benefits, and Selection of Subjects [3].

Application: Informed Consent

The application of Informed Consent flows directly from the principle of Respect for Persons. To respect individual autonomy, researchers must ensure subjects enter research voluntarily and with adequate information [1].

Table 2: Essential Elements of Valid Informed Consent

| Element Category | Specific Component | Technical Requirement | Ethical Principle Served |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information | Research procedures & purposes | Disclosed in comprehensible language | Respect for Persons |

| Risks & anticipated benefits | Clearly explained, including likelihood | Beneficence | |

| Alternative procedures | Disclosed (where therapy is involved) | Respect for Persons, Beneficence | |

| Comprehension | Subject understanding | Information presented in understandable manner | Respect for Persons |

| Adaptation to subject capacity | Tailored to subject's comprehension level | Respect for Persons | |

| Voluntariness | Absence of coercion | Free power of choice without constraint | Respect for Persons, Justice |

| Right to withdraw | Statement offering subject opportunity to ask questions and withdraw at any time | Respect for Persons |

Application: Assessment of Risks and Benefits

The systematic Assessment of Risks and Benefits is the practical application of the principle of Beneficence. This requires a careful, systematic documentation and analysis of all potential risks and benefits, both to individual subjects and to society at large [1]. Researchers and IRBs must distinguish between the scientific validity of a research design and the assessment of risks and benefits, as a poorly designed study inherently exposes subjects to risk without the potential benefit of valuable knowledge [1]. The assessment process must be rigorous and factual, considering alternative ways to obtain the benefits sought.

Application: Selection of Subjects

The Selection of Subjects is the primary application of the principle of Justice. It requires scrutiny to ensure that the burdens of research are not disproportionately borne by any particular group, especially those vulnerable to exploitation, while the benefits of research are distributed fairly [6]. Research should not systematically select certain groups (e.g., participants receiving public financial assistance, specific ethnic and racial minorities, or the institutionalized) simply because of their easy availability or compromised position [1]. The inclusion and exclusion criteria must be based on factors that most effectively and soundly address the research problem, not social convenience [1].

Diagram 1: Belmont Report Principles to Application Mapping

Methodological Implementation: The Researcher's Toolkit

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocol

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) serves as the primary mechanism for enforcing the ethical principles of the Belmont Report in research practice [6]. Researchers must submit a complete research proposal to the IRB, including specific data collection instruments, research advertisements, and informed consent documentation before initiating any research activities [6]. The IRB review process involves:

- Full Committee Review: Required for research involving more than minimal risk

- Expedited Review: For certain categories of research involving no more than minimal risk

- Exempt Determination: For specific categories of research that qualify for exemption

The IRB composition intentionally includes experts across various disciplines, including ethicists, social workers, physicians, nurses, scientific researchers, and legal experts to provide comprehensive ethical oversight [6].

Research Reagent Solutions: Ethical Implementation Framework

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Ethical Research Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Protocol | Details all research procedures and methodologies for IRB review | Must include specific data collection instruments, advertisements, and consent documentation [6] |

| Informed Consent Documentation | Ensures voluntary participation with adequate information | Must include research procedures, purposes, risks, benefits, alternatives, and right to withdraw [1] [6] |

| Vulnerable Population Safeguards | Provides additional protections for vulnerable groups | Requires special consent procedures, assent for children, and additional oversight [6] |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment Framework | Systematically analyzes potential harms and benefits | Must document all potential risks (physical, psychological, social, economic) and benefits [1] |

| Data Confidentiality Protocols | Protects participant privacy and confidentiality | Includes procedures for data anonymization, secure storage, and confidentiality assurance [6] |

| Subject Selection Justification | Ensures equitable selection of research subjects | Must document that selection is based on scientific requirements, not convenience or vulnerability [1] |

Risk-Benefit Assessment Methodology

The assessment of risks and benefits requires a systematic, analytical approach guided by the following methodological considerations:

- Brutal Data Collection: Gather complete information about all aspects of the research, considering even remote possibilities of harm

- Systematic Consideration of Alternatives: Evaluate whether comparable knowledge could be gained through less-risky methods

- Non-arbitrary Analysis: Ensure the assessment process is rigorous and based on factual evidence rather than intuition

- Ongoing Evaluation: Continue assessment throughout the research lifecycle, not just during initial review

This methodological framework ensures that the analysis of risks and benefits is comprehensive and scientifically valid, fulfilling the ethical obligation of beneficence.

Diagram 2: Ethical Research Protocol Implementation Workflow

Discussion: Contemporary Relevance in Research

The Belmont Report's principles continue to provide the fundamental framework for ethical research conduct, particularly in the evolving landscape of drug development and clinical trials. The principles have been clearly reflected in regulations governing gene therapy clinical trials and policies regarding public review of protocols [3]. For modern researchers and drug development professionals, these principles offer a robust structure for addressing emerging ethical challenges in areas including:

- Precision Medicine: Ensuring equitable access to emerging targeted therapies

- Genetic Research: Protecting privacy and autonomy in the context of complex genetic information

- Global Clinical Trials: Applying justice principles to prevent exploitation in international research settings

- Digital Health Technologies: Assessing risks and benefits in rapidly evolving technological environments

- Vulnerable Population Research: Maintaining rigorous protections while enabling essential research

The three principles provide a comprehensive framework that continues to guide researchers in balancing scientific advancement with rigorous ethical practice, ensuring that the fundamental rights and welfare of human subjects remain protected in an increasingly complex research landscape.

The Belmont Report, formally titled "Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research," was published in 1979 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [3] [1]. This foundational document emerged in response to historical abuses in human subjects research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where uninformed and unaware patients were exposed to disease or subjected to unproven treatments without their consent [6] [7]. The report established three fundamental ethical principles to govern research involving human subjects: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice [8] [9].

The principle of respect for persons serves as the ethical foundation for the treatment of human research participants and incorporates two distinct but related ethical convictions [8] [9]. First, individuals should be treated as autonomous agents capable of making responsible choices and determining their own life course. Second, persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to special protections to safeguard their well-being and rights [1]. This principle divides into two moral requirements: the requirement to acknowledge autonomy through informed consent processes, and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy through additional safeguards [8]. Within the framework of the Belmont Report, respect for persons finds its primary application in the process of informed consent, ensuring that individuals voluntarily choose whether to participate in research after receiving comprehensive information presented in an understandable format [9].

Core Components of Respect for Persons

Autonomy in Research Ethics

The concept of autonomy is central to the principle of respect for persons. An autonomous person is "an individual capable of deliberation about personal goals and acting under the direction of such deliberation" [6]. In research practice, respecting autonomy means acknowledging individuals' right to make their own decisions without coercion or undue influence [10]. Researchers must ensure participants have the right to self-determination, including the right to decide whether to participate voluntarily, to ask questions, and to comprehend the questions asked by the researcher [6].

Cultural considerations significantly influence the practical application of autonomy. Western societies typically emphasize individual autonomy, where decision-making revolves around a single person. In contrast, collectivistic cultures often practice collective autonomy, where decision-making is group-oriented, shared, or designated to specific individuals [11]. For example, research involving South Asian immigrants may require a family-centered approach to decision-making, while working with Indigenous groups may necessitate deference to tribal leaders or community gatekeepers [11]. These cultural variations require researchers to adopt culturally sensitive approaches to autonomy that respect diverse decision-making frameworks while maintaining ethical integrity.

Informed Consent Process

Informed consent represents the practical application of respect for persons in research settings [9]. The Belmont Report analyzes the consent process as containing three essential elements: information, comprehension, and voluntariness [9]. Each element must be adequately addressed to ensure meaningful consent rather than mere ritualistic documentation.

Information: Researchers must provide complete details about the research study, including procedures, purposes, risks and anticipated benefits, alternative procedures (where therapy is involved), and a statement offering subjects the opportunity to ask questions and to withdraw at any time [1]. The information must be presented in language understandable to the participant, avoiding technical jargon that might obscure meaning.

Comprehension: Researchers must ensure that potential participants truly understand the information provided. This requires presenting information in a manner commensurate with the participant's comprehension level and ensuring the communication process is effective [9]. For populations with educational disadvantages or cognitive impairments, researchers may need to employ additional strategies to verify understanding.

Voluntariness: Consent must be given voluntarily without coercion or undue influence [9]. Researchers must avoid threats of penalty (whether explicit or implied) for declining participation and must carefully consider whether excessive rewards might compromise voluntary choice [6]. The environment and power dynamics between researcher and participant can significantly impact voluntariness.

Table 1: Essential Elements of Valid Informed Consent

| Element | Key Requirements | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Information Disclosure | Research procedures, purposes, risks, benefits, alternatives, right to withdraw | Use of technical jargon, overwhelming detail, omission of significant risks |

| Comprehension | Information tailored to participant understanding, verification of understanding | Assuming understanding without assessment, ignoring cultural/language barriers |

| Voluntariness | Absence of coercion or undue influence, freedom to refuse without penalty | Power differentials, excessive incentives, implicit pressure from researchers |

Protecting Persons with Diminished Autonomy

The second ethical conviction within respect for persons recognizes that some individuals have diminished autonomy and require additional protections [8]. The extent of protection should be proportionate to the risk of harm and likelihood of benefit, and the judgment about an individual's autonomy should be periodically reevaluated as it may vary in different situations [1]. Certain populations are specifically identified as vulnerable in federal regulations, while others may exhibit nuanced vulnerability depending on contextual factors [11].

Table 2: Populations with Diminished Autonomy and Protective Considerations

| Population | Nature of Vulnerability | Recommended Protections |

|---|---|---|

| Children | By regulatory definition, persons who have not attained legal age for consent [11] | Parental permission and child assent (for children 7+), justification for inclusion based on research purpose [6] [11] |

| Prisoners | Involuntarily confined individuals with compromised ability to refuse [8] [11] | Prisoner representative on IRB, ensure benefits not overly influential, fair selection procedures [8] [11] |

| Individuals with Impaired Decision-Making Capacity | Wide variety of conditions affecting understanding and weighing of information [11] | Periodic check-ins, assessment of consent capacity, surrogate decision-makers, assent when possible [6] [11] |

| Economically/Eductionally Disadvantaged | Potential vulnerability to undue influence due to limited resources [11] | Additional safeguards against coercion, tailored communication approaches, consideration of alternative consent documentation [11] |

| Culturally Vulnerable Groups | Historical exploitation or different decision-making norms [11] | Cultural humility, community consultation, collective consent approaches when appropriate [11] |

Practical Applications and Methodologies

Implementing Ethical Protocols

Translating the principle of respect for persons into actionable research protocols requires systematic approaches at each stage of the research process. The following workflow illustrates the key stages in implementing ethical protocols for respect for persons:

For research involving vulnerable populations with impaired decision-making capacity, specific methodological approaches are necessary:

Capacity Assessment Protocols: Implement brief, validated tools to assess potential participants' understanding of research elements, including purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives [11]. Document assessment results and capacity determination.

Surrogate Decision-Maker Engagement: Identify legally authorized representatives according to state hierarchy (typically spouse, adult children, parents, siblings) [12]. Provide complete information to surrogates and ensure they understand their role in representing the participant's best interests and known preferences.

Assent Procedures: Even when formal consent comes from a surrogate, seek affirmative agreement from participants with diminished autonomy to the extent of their capabilities [6]. Use age-appropriate or capacity-appropriate materials and periodically re-evaluate willingness to continue participation.

Cultural Consultation: For research involving cultural subgroups, engage cultural consultants or community advisory boards during study design to ensure appropriate consent approaches [11]. This may involve community-level consent before individual consent in some Indigenous populations.

Assessment Tools and Documentation

Robust assessment and documentation are essential for demonstrating adherence to the principle of respect for persons. Researchers should employ multiple methods to verify understanding and maintain comprehensive records of the consent process:

Teach-Back Method: Ask participants to explain the study in their own words to verify comprehension of key elements including purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and voluntary nature [6].

Decisional Capacity Assessments: For populations with potential cognitive impairments, use structured assessments such as the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) to evaluate understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and expression of choice [11].

Vulnerability Mitigation Checklists: Develop population-specific checklists to ensure appropriate safeguards are implemented, such as independent witnesses for consent processes, additional educational materials, or community advocate involvement [11].

Cultural Sensitivity Reviews: Have consent materials and processes reviewed by individuals familiar with the cultural context of the participant population to identify potential barriers or unintended cultural offenses [11].

Table 3: Research Ethics Toolkit for Respect for Persons

| Tool Category | Specific Instruments | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehension Verification | Teach-back method, Quizzes, Open-ended questioning | All research populations, especially with complex protocols or educational limitations |

| Capacity Assessment | MacCAT-CR, UBACC, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | Research involving elderly, cognitively impaired, or psychiatric populations |

| Cultural Adaptation | Community advisory boards, Cultural consultants, Translated materials | Research with ethnic minorities, Indigenous populations, or international sites |

| Documentation Alternatives | Verbal consent with witnesses, Electronic consent with multimedia, Short forms | Populations with literacy challenges, undocumented individuals, low-risk studies |

Institutional Review Board Evaluation Criteria

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) systematically evaluate research protocols to ensure compliance with the principle of respect for persons. Researchers should be prepared to address the following criteria during IRB review [1] [6]:

Consent Process Rigor: The IRB examines the proposed consent process for completeness of information, appropriateness for the participant population, and procedures to ensure comprehension and voluntariness [6]. Boards may require simplified language, visual aids, or independent consent monitors for vulnerable populations.

Vulnerability Assessment: Researchers must justify the inclusion of vulnerable populations and demonstrate appropriate safeguards [6] [11]. The IRB evaluates whether the research could be conducted with less vulnerable populations and whether risks are justified by potential benefits to participants or the vulnerable group.

Cultural Competence: The IRB assesses whether researchers have demonstrated understanding of and appropriate approaches to cultural factors that may impact participant autonomy and decision-making [11]. This includes consideration of collective decision-making norms, language barriers, and historical trauma.

Privacy and Confidentiality: Protocols must include adequate measures to protect participant privacy through data anonymization or confidentiality through secure data handling [6]. The IRB evaluates these measures in relation to the sensitivity of the data collected.

Contemporary Challenges and Evolving Considerations

Nuanced Vulnerabilities in Modern Research

While federal regulations specify certain vulnerable populations, contemporary research recognizes the concept of nuanced vulnerability - groups that may not be listed in regulations but require augmented protections depending on context [11]. These include:

Undocumented Immigrants: Who may fear that signing consent forms could have legal repercussions, requiring alternatives to standard written documentation [11].

Gender-Oppressed Groups: Women in certain cultural contexts whose decision-making may be constrained by familial or religious structures, necessitating consultation with designated family members [11].

Historically Exploited Communities: Such as Native American tribes with historical trauma from previous research exploitation, requiring community engagement and sometimes tribal approval before individual consent [11].

Researchers must practice cultural humility - an ongoing process of self-reflection and self-critique about cultural norms and recognition of power imbalances in researcher-participant relationships [11]. This approach acknowledges that researchers cannot be complete experts on other cultures but must engage in lifelong learning to develop mutually beneficial and respectful research partnerships.

Regulatory Framework and Global Applications

The principles outlined in the Belmont Report continue to influence contemporary regulatory frameworks, including the International Council for Harmonisation's (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R3) [7]. The report's enduring relevance nearly five decades after its publication demonstrates the robustness of its ethical framework while requiring adaptation to evolving research contexts [7].

The Common Rule (45 CFR Part 46) codifies the principles of the Belmont Report into federal regulations governing human subjects research in the United States [12] [7]. Additional FDA regulations (21 CFR Parts 50, 56) provide specific requirements for informed consent and IRB operations in clinical investigations [12]. State statutes may provide additional protections, such as California's requirements for minor assent in experimental drug studies [12].

In global research contexts, the principle of respect for persons requires careful navigation of diverse cultural norms while maintaining ethical essentials. This may involve implementing multi-level consent processes (community, familial, and individual) in collectivist cultures while still ensuring individual participants understand they may decline participation without collective repercussions [11]. The fundamental requirements of understanding, voluntariness, and protection of vulnerable individuals remain constant across cultural contexts, though their implementation may vary appropriately.

The principle of respect for persons, as articulated in the Belmont Report, remains a cornerstone of ethical research involving human subjects nearly five decades after its publication [7]. Its two-fold requirement - to acknowledge autonomy through informed consent processes and to protect those with diminished autonomy through additional safeguards - provides a robust framework for ethical decision-making in research [8] [1]. As research methodologies and participant populations evolve, the enduring relevance of this principle requires researchers to continually adapt its application to new contexts while maintaining fidelity to its ethical foundations. By embracing both the letter and spirit of respect for persons through culturally humble practices, rigorous consent processes, and appropriate protections for vulnerable populations, researchers honor the dignity and worth of every individual who contributes to the advancement of knowledge through research participation.

Within the foundational ethical framework of the Belmont Report, the principle of beneficence imposes a dual obligation upon researchers: to "do no harm" and to "maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms" [1]. This principle extends beyond merely refraining from inflicting injury; it requires an active commitment to securing the well-being of research participants and society at large [1]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, navigating this dual obligation is a complex, continuous process integral to every stage of experimental design and execution. Beneficence ensures that the research enterprise is not only scientifically valid but also ethically defensible, demanding a rigorous and systematic assessment of risks and benefits long before the first participant is enrolled [13]. This guide provides a technical roadmap for applying this critical principle, featuring structured frameworks for risk-benefit analysis, practical methodological checklists, and visualization of ethical decision-making pathways to uphold the highest standards of research integrity.

The Ethical Framework of Beneficence

Historical and Regulatory Context

The Belmont Report, published in 1979, emerged as a direct response to historical ethical failures in research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [7]. It established beneficence as one of three core principles—alongside Respect for Persons and Justice—that would form the bedrock for modern regulations protecting human subjects [1] [3]. This principle was codified into U.S. federal law through the Common Rule (45 CFR 46), which governs nearly all federally funded human subjects research in the United States [14]. The Belmont Report's enduring influence is further evidenced by its alignment with contemporary guidelines, such as the International Council for Harmonisation's (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R3), which is followed by clinical researchers worldwide [7].

The Dual Rules of Beneficence

The principle of beneficence is operationalized through two complementary moral rules [1]:

- Do not harm: This rule, often associated with the Hippocratic tradition, prohibits the intentional infliction of injury or harm on research subjects.

- Maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms: This positive obligation requires researchers to proactively enhance the value of the research while systematically reducing and managing its inherent risks.

In practice, these rules necessitate that any risks to participants must be justified by the anticipated benefits, either to the individual subject or to society through the advancement of knowledge [1] [13]. This favorable risk-benefit ratio is a cornerstone of ethical research and a primary focus for Institutional Review Board (IRB) review [13].

Operationalizing Beneficence: A Methodological Framework

Systematic Risk-Benefit Assessment

A rigorous, non-arbitrary assessment of risks and benefits is the primary methodology for fulfilling the obligation of beneficence. The Belmont Report itself outlines a method for IRBs to use in this determination, which researchers should preemptively apply during study design [1]. The process involves gathering and assessing all available information on the research components and systematically considering alternatives.

Table: Taxonomy of Research Risks and Benefits

| Category | Types & Examples | Assessment Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Risks | Physical: Pain, infection, side effects from an investigational drug [13].Psychological: Stress, anxiety, emotional distress [13].Social: Stigma, breach of confidentiality, impact on employability [13].Economic: Financial costs of participation, travel time, lost wages [13]. | - Probability of occurrence.- Severity (trivial to serious).- Duration (transient to long-term).- Reversibility. |

| Benefits | Direct to Subject: Access to a potentially therapeutic intervention, improved health monitoring, financial compensation [14].Societal: Acquisition of generalizable knowledge to improve future health, development of new diagnostic tools or treatments [1] [14]. | - Likelihood of realization.- Magnitude.- Specificity to the participant population. |

The Risk-Benefit Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic, iterative workflow required for a ethically sound risk-benefit assessment, from initial identification through to final IRB review and ongoing monitoring.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Ethical Research

Upholding beneficence requires more than ethical intent; it relies on specific tools and documents that structure and document the protection of participant welfare.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Practice

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Upholding Beneficence |

|---|---|

| Protocol with Stopping Rules | A pre-defined, detailed research plan that includes clear stopping rules and safety thresholds to prevent undue harm. |

| Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) | An independent committee of experts that reviews accumulated data from a clinical trial at intervals to ensure participant safety and study validity. |

| Informed Consent Document | The primary tool for communicating the research's foreseeable risks, potential benefits, and alternatives to potential participants [1] [13]. |

| Adverse Event (AE) Reporting System | A standardized system for capturing, documenting, and reporting any untoward medical occurrences in a research participant. |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) Application | The formal submission that justifies the research to an independent review panel, demonstrating a favorable risk-benefit ratio and ethical design [13]. |

Navigating Complexities and Conflicts

Balancing Beneficence with Other Ethical Principles

The ethical principles of the Belmont Report do not exist in isolation and can sometimes conflict. A classic example occurs in research involving children. The principle of Respect for Persons requires honoring a child's dissent, while Beneficence might argue for a potential direct therapeutic benefit from participation, and Justice supports including children in research to gain knowledge relevant to their health conditions [14]. Regulatory frameworks provide guidance for resolving these tensions; for instance, in greater-than-minimal risk research offering direct benefit to the child, an IRB may allow a parent's permission to override a child's dissent in the interest of the child's well-being (favoring Beneficence) [14].

The Challenge of Uncertainty

A fundamental challenge in applying beneficence is the inherent uncertainty about the degree of risks and benefits in any clinical research study [13]. By definition, research seeks to answer questions for which the answers are not yet known. This underscores the necessity of the systematic assessment process, ongoing monitoring, and the communication of this uncertainty to participants during the informed consent process [13].

The framework of beneficence remains critically relevant in addressing modern research challenges. The rise of Dual Use Research of Concern (DURC)—research with a legitimate scientific purpose that could be misapplied to pose a significant threat—explicitly engages the principle of beneficence by forcing a consideration of potential harms to public health and security on a broad scale [15]. Similarly, recent federal initiatives like the U.S. Gold Standard Science executive order, which emphasizes reproducibility, transparency, and communication of error, are rooted in the beneficent goal of ensuring reliable and credible science [16].

In conclusion, for the research professional, beneficence is not a passive ideal but an active, methodological practice. It requires a vigilant, systematic, and documented commitment to the dual obligation of avoiding harm and optimizing benefits throughout the research lifecycle. By integrating the structured assessments, workflows, and tools outlined in this guide, researchers can ensure their work not only advances scientific knowledge but also faithfully honors the trust placed in them by participants and society.

The Belmont Report, published in 1978, establishes a foundational ethical framework for research involving human subjects, built upon three core principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice [7] [1]. This guide focuses on the principle of justice, which pertains to the fair distribution of the benefits and burdens of research [17]. In practice, justice requires that the selection of research subjects must be scrutinized to avoid systematic selection based on easy availability, compromised position, or societal manipulability [18]. Instead, subject selection should be based on factors directly related to the research problem, ensuring that no specific group (whether defined by gender, race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status) is unfairly burdened with the risks of research or denied its benefits [18] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, operationalizing this principle is a critical component of ethical study design and regulatory compliance.

The Conceptual Framework of Justice

Historical Context and Ethical Foundations

The emphasis on justice in research ethics arose from a history of exploitative practices where the burdens of research fell disproportionately on vulnerable populations. The Belmont Report itself cites historical examples, including:

- Poor ward patients in the 19th and early 20th centuries who bore the burdens of research while benefits flowed primarily to private patients.

- Unwilling prisoners in Nazi concentration camps who were exploited as research subjects.

- Disadvantaged rural Black men in the Tuskegee syphilis study, who were deprived of effective treatment long after it became available [18].

These injustices highlighted the need for a systematic application of justice to ensure the fair selection of subjects and equitable distribution of research risks and benefits.

Conceptions of Justice in Research

The Belmont Report primarily embodies a conception of distributive justice—the fair allocation of society's benefits and burdens [18]. However, other conceptions are also relevant:

- Distributive Justice: Pertains to the fair allocation of the benefits and burdens of research. It requires that no one group should receive disproportionate benefits or bear disproportionate burdens [18].

- Procedural Justice: Applies to matters where a fair result depends on adherence to well-ordered procedures, such as the requirements of due process in informed consent and Institutional Review Board (IRB) review [18].

- Compensatory Justice: Goes beyond fairness in distribution to remedy or redress past wrongs, such as the monetary payments made to survivors of the Tuskegee syphilis study [18].

A key requirement of justice in research is a "fitting" match: the population from which research subjects are drawn should reflect the population to be served by the results of the research [18].

Regulatory and Guidance Framework

The Common Rule and International Harmonization

The ethical principles of the Belmont Report are codified in the U.S. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, known as the Common Rule (45 CFR 46) [17] [7]. The Common Rule mandates that research conducted or funded by federal agencies must adhere to requirements for informed consent, IRB review, and equitable subject selection [17].

For global drug development, sponsors must navigate both the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines and U.S.-specific regulations [19]. While both frameworks are rooted in the same ethical principles, critical distinctions exist:

Table: Comparison of ICH Guidelines and U.S. Common Rule

| Feature | ICH Guidelines | U.S. Common Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Clinical trials for pharmaceuticals [19] | Broad range of human subjects research [19] |

| Legal Status | Recommendations adopted into national laws [19] | Legally binding regulation in the U.S. [19] |

| IRB Composition | -- | Emphasizes diversity (race, gender, culture, profession) [19] |

| Documentation | -- | Often requires more extensive documentation and financial disclosures [19] |

Contemporary FDA Guidance on Representativeness

Recent FDA draft guidances emphasize the importance of representativeness in clinical trials, particularly for multiregional clinical trials (MRCTs). Key considerations include:

- U.S. Participant Representation: Data submitted for FDA marketing approval should include results from a substantial number of U.S. participants, even if subjects in other regions share similar characteristics [19].

- Standard of Care Evaluation: Differences in standard-of-care treatment at foreign sites compared to the U.S. must be evaluated [19].

- Beyond Demographics: Representativeness should consider Social Determinants of Health (e.g., socioeconomic status, healthcare access, environmental factors) that significantly impact health outcomes and treatment responses, moving beyond mere racial and ethnic categories [19].

Practical Application: Methodologies for Ensuring Justice

Designing Equitable Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The first step in ensuring justice is the formulation of study eligibility criteria that are scientifically justified and non-discriminatory.

- Protocol Development Tool: The following diagram outlines a decision pathway for developing equitable study criteria.

Strategies for Recruiting a Representative Sample

Achieving a representative sample requires proactive, structured strategies. The following experimental protocol provides a methodological framework for recruitment.

Table: Protocol for Recruiting a Representative Sample

| Protocol Step | Detailed Methodology | Tools & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Population Mapping | Analyze disease epidemiology and demographics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, geography) from public health data and electronic health records. | U.S. Census data; CDC databases; institutional data warehouses; ensure data includes social determinants of health [19]. |

| 2. Site Selection | Choose clinical sites based on their patient population's alignment with the mapped epidemiology, including sites that serve diverse and underserved communities. | Community health centers; academic medical centers; VA hospitals; assess site cultural competency [19]. |

| 3. Outreach & Consent | Develop multilingual, culturally appropriate materials and consent forms. Use community-based participatory research principles. | Patient advocacy groups; community advisors; plain language guides; digital and non-digital outreach [18]. |

| 4. Barrier Mitigation | Implement practical support for participants: transportation vouchers, flexible scheduling, compensation for time and travel. | Budget for participant reimbursements; childcare services; virtual visit options where scientifically valid. |

| 5. Monitoring & Reporting | Continuously track enrollment demographics against pre-defined targets. Report progress to the IRB and study leadership. | Centralized tracking system; regular diversity reports; adaptive strategies if targets are not met [19]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit for Equitable Research

Table: Essential Reagents and Solutions for Implementing Justice

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| IRB (Institutional Review Board) | An independent committee that reviews and monitors research to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects. Ensures equitable selection of subjects [17] [1]. |

| Informed Consent Form | A critical document that ensures respect for persons by providing prospective subjects with all necessary information in an understandable format, allowing them to make a voluntary decision about participation [1]. |

| Community Advisory Board | A group of community representatives that provides input on study design, recruitment strategies, and consent materials to ensure cultural and ethical appropriateness. |

| Data Diversity Dashboard | A real-time tracking tool (e.g., table, chart) that monitors enrollment demographics against pre-defined targets to ensure the study population is representative [19]. |

| Centralized IRB | For multi-site trials, a central IRB can help ensure consistent application of ethical standards and equitable subject selection practices across all sites [19]. |

Data Analysis and Presentation for Justice

Summarizing and Comparing Participant Data

A fundamental step in demonstrating justice is the clear presentation of study population characteristics. This allows reviewers to assess the generalizability of findings and the fairness of subject selection [20]. For quantitative data comparing groups, appropriate numerical summaries and graphs are essential [21].

Table: Participant Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Overall (N=85) | Group A (n=26) | Group B (n=59) | Difference (A - B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 40.2 | 45.0 | 38.1 | 6.9 |

| Median Age (years) | 37.0 | 46.5 | 35.0 | -- |

| Std. Deviation (Age) | 13.90 | 14.04 | 13.44 | -- |

| Mean Household Size | 8.4 | 10.5 | 7.5 | 3.0 |

| Median Household Size | 7.0 | 8.5 | 6.0 | -- |

| IQR (Household Size) | 6.00 | 7.75 | -- | -- |

Source: Adapted from example data on household characteristics [21]

Visualizing Distributions for Comparison

Effective data visualization is key to communicating distribution and comparisons. The choice of graph depends on the data type and the story to be told [22] [20].

- Boxplots: Best for comparing distributions across groups, showing medians, quartiles, and potential outliers. They are excellent for visualizing the center and spread of data [21] [20].

- Bar Charts: Ideal for comparing summary statistics (e.g., mean values) between discrete categories [22].

- Histograms: Used to show the frequency distribution of a continuous variable, helping to assess the shape of the data [22].

The following workflow diagram guides the selection of an appropriate comparative visualization based on the data structure and objective, ensuring clear and ethical presentation of study populations and outcomes.

The principle of justice, as articulated in the Belmont Report, remains a vital and dynamic force in shaping ethical research conduct. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, moving beyond mere regulatory compliance to a proactive commitment to justice is imperative. This involves designing studies with equitable inclusion criteria, implementing robust strategies to recruit representative samples, and transparently reporting participant demographics. By rigorously applying these principles and methodologies, the research community can ensure that the benefits and burdens of science are shared fairly, fostering trust and advancing health equity for all.

From Theory to Practice: Applying Belmont Report Principles in Clinical Research and Drug Development

The Belmont Report, formulated in 1979, established an enduring ethical framework for research involving human subjects. Its creation was a direct response to ethical transgressions in studies such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where participants were denied treatment and deceived for decades [23] [24]. The report articulates three fundamental ethical principles: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [2] [25]. Of these, the principle of Respect for Persons forms the foundational imperative for the informed consent process, requiring that individuals are treated as autonomous agents and that those with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [2]. This guide provides a technical roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to operationalize this principle, translating ethical theory into rigorous, respectful, and effective research practice.

The Ethical and Regulatory Foundations of Informed Consent

The Principle of Respect for Persons

The Belmont Report breaks down the principle of Respect for Persons into two key tenets: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [2]. The application of this principle is not merely a regulatory hurdle; it is a critical factor in building and maintaining trust in clinical research [26]. When participants feel respected, they are more likely to engage, remain in studies, and contribute to the integrity of the research data.

Informed consent is the primary mechanism through which respect for persons is realized. It is fundamentally a process—not a single event or a form to be signed—that begins with the initial recruitment and continues throughout the participant's involvement in the study [27]. The Belmont Report specifically defines informed consent as being comprised of three critical elements: information, comprehension, and voluntariness [23]. This framework ensures that consent is not just legally documented but is meaningfully given.

From Belmont to Regulation: The Requirements for Consent

The ethical principles of the Belmont Report are codified in the Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46), which provide the specific elements that must be included in the informed consent process and documentation [25] [24]. The 2018 revision to the Common Rule emphasized the need for a "concise and focused" presentation of key information at the beginning of the consent document to help potential participants understand why they might or might not want to take part [27].

Table: Key Information Elements for Informed Consent as per the Revised Common Rule

| Element Number | Description of Key Information element |

|---|---|

| 1 | A statement that the project is research and that participation is voluntary. |

| 2 | A summary of the research (purpose, duration, and procedures). |

| 3 | A description of reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts. |

| 4 | A description of reasonably expected benefits. |

| 5 | A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any. |

Beyond these key elements, the regulations stipulate additional required elements for full disclosure, such as how confidentiality will be maintained, the availability of compensation for injuries, whom to contact for questions, and the conditions under which participation may be terminated [27].

A Framework for Operationalizing Respect

Moving from regulatory checkboxes to a meaningful consent process requires a deliberate strategy. The following framework, derived from ethical principles and empirical research, outlines this progression.

Element 1: Providing Sufficient Information

The first element requires that subjects are provided with all information material to their decision. This goes beyond simply listing risks and benefits; it involves presenting a complete and honest picture of the research. Researchers must avoid technical jargon and present information in straightforward language that is understandable to the participant population, typically at an 8th-grade reading level [27]. A best practice is to have a colleague or friend read the informed consent document for comprehension before it is submitted for IRB review [27].

Element 2: Ensuring Participant Comprehension

The Belmont Report states that "the manner and context in which information is conveyed is as important as the information itself" [23]. Simply providing information is insufficient if the participant does not understand it. Researchers must actively facilitate comprehension by considering the subject's maturity, capacity for understanding, language, and literacy [23]. This can involve:

- Allowing ample time for the subject to consider the information [23].

- Using comprehension tests or teach-back methods, where participants explain the study in their own words [23].

- Employing multimedia aids or culturally and linguistically appropriate materials.

This is particularly crucial when working with populations that may have diminished autonomy or cognitive impairments, where extra protections and adapted communication strategies are necessary [28] [2].

Element 3: Guaranteeing Voluntariness

An agreement to participate is only valid if it is made voluntarily, free from any form of coercion or undue influence [23] [25]. This means researchers cannot threaten harm or offer an "excessive, unwarranted, inappropriate or improper reward" to obtain compliance [23]. Special care must be taken when enrolling vulnerable individuals who are under the authority of others, such as prisoners, employees, or the very sick [28] [23]. The consent process must make it clear that participation is entirely voluntary and that the participant can withdraw at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which they are otherwise entitled [25] [24].

Practical Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Developing and Assessing a Consent Document

A rigorous, multi-step protocol ensures the consent document is both ethically sound and practically effective.

Table: Protocol for Consent Document Development and Assessment

| Step | Action | Rationale & Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Drafting | Use an institutional template that includes all Common Rule elements [27]. | Ensures regulatory compliance. |

| 2. Tailoring | Adapt language, examples, and reading level to the specific subject population [27]. | Enhances relevance and accessibility. |

| 3. Internal Review | Have a colleague unfamiliar with the study read for comprehension [27]. | Identifies jargon and complex sections. |

| 4. Pilot Testing | Test the document with a small group representative of the study population. | Gathers feedback on clarity and understanding. |

| 5. Revision | Incorporate feedback to simplify and clarify the document. | Improves overall quality and effectiveness. |

| 6. IRB Submission | Submit the final document and process description for ethics review. | Fulfills institutional and federal oversight requirements. |

Methodology for a Patient-Centered Consent Process

Recent research emphasizes moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach. A 2023 modified Delphi study engaged patients to identify what they value most in the consent process [29]. The study found that participants prioritized two key areas:

- The provision of study information to support decision-making.

- Interactions with research staff characterized by kindness, patience, and a lack of judgment [29].

This patient-centered methodology can be integrated into standard practice by:

- Training research staff in empathetic communication and active listening skills.

- Structuring the consent conversation as a two-way dialogue rather than a monologue.

- Creating a comfortable environment where questions are encouraged and answered patiently.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Ethical Consent

Successfully implementing a meaningful consent process requires more than just a form. The following toolkit comprises essential resources for the modern researcher.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for the Informed Consent Process

| Tool or Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| IRB-Approved Consent Template | Pre-formatted document (e.g., from university HRPP office) ensuring all required regulatory elements and institutional language are included [27]. |

| Plain Language Guidelines | Resources (e.g., plainlanguage.gov) to help translate complex scientific and technical terms into language accessible to a lay audience [27]. |

| Readability Analyzer | Software tool (e.g., in Microsoft Word) to objectively assess and target an 8th-grade reading level in the consent document [27]. |

| Multi-Media Aids | Videos, diagrams, and interactive digital platforms to supplement written text and cater to different learning styles. |

| Teach-Back Script | A structured guide for researchers to ask participants to explain the study in their own words, verifying true comprehension [23]. |

| Cultural & Linguistic Resources | Access to certified translation services and cultural consultants to ensure the process is appropriate for diverse populations. |

Addressing Contemporary Challenges and Vulnerabilities

Navigating Vulnerability with an Analytical Approach

While early ethical guidelines often employed a "group-based" or "labeling" approach to vulnerability (e.g., classifying all prisoners or children as vulnerable), modern scholarship advocates for a more nuanced "analytical approach" [28]. This approach focuses on identifying the specific sources of vulnerability in a research context, which often fall into three categories:

- Consent-based accounts: Vulnerability stems from a compromised capacity to provide free and informed consent.

- Harm-based accounts: Vulnerability arises from a higher probability of incurring harm during research.

- Justice-based accounts: Vulnerability is linked to systemic inequalities and unfair distribution of research burdens and benefits [28].

Researchers should conduct a vulnerability analysis for their study population and implement targeted safeguards. For instance, for a participant with low health literacy (a consent-based vulnerability), the use of a teach-back method is an appropriate specific safeguard.

Building Trust through Transparency and Empowerment

Trust is not a static given; it is an emergent property that develops through complex interactions within the research ecosystem [26]. It is cultivated at multiple levels: individual (researcher-participant), team, organizational, and system-wide. Key elements for building trust include transparency, respect, autonomy, and empowerment [26]. This means:

- Being transparent about data use and study results.

- Respecting participants' time, values, and perspectives.

- Protecting their autonomy throughout the study, not just at consent.

- Empowering them with knowledge and confidence.

This is especially critical when engaging with marginalized communities that harbor a historical and justified distrust of research [29] [26]. A meaningful consent process is a powerful first step in rebuilding this trust.

A meaningful informed consent process is the practical embodiment of the Belmont Report's principle of Respect for Persons. It demands that researchers move beyond a regulatory checklist and embrace their ethical duty to ensure participants are truly informed, comprehend the research, and volunteer freely. By adopting the structured frameworks, protocols, and tools outlined in this guide—and by centering the values and perspectives of participants—researchers and drug development professionals can uphold the highest ethical standards. This commitment not only protects participants but also enhances the scientific validity and societal value of the research itself.

The conduct of ethical research is anchored in the systematic assessment of risks and benefits. This process is fundamentally guided by the three core principles established by the Belmont Report: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [1]. This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a technical framework for integrating these principles into their study protocols through a rigorous and transparent risk-benefit assessment. Adherence to this framework is essential for protecting human subjects and ensuring the scientific and ethical integrity of clinical research.

Core Ethical Principles and Their Application to Risk-Benefit Assessment

The Belmont Report's principles provide the ethical justification for risk-benefit assessments. The following table outlines their core tenets and direct application to protocol development.

Table 1: Applying Belmont Report Principles to Risk-Benefit Assessment

| Ethical Principle | Core Tenet | Application in Study Protocol Design |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Recognizing participant autonomy and protecting those with diminished autonomy [1]. | - Obtaining informed consent through a complete disclosure of risks, benefits, and alternatives.- Implementing robust data privacy and confidentiality safeguards. |

| Beneficence | The obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [1]. | - Designing a sound scientific protocol to ensure the research is valid and valuable.- Implementing risk minimization strategies (e.g., safety monitoring, data safety monitoring boards). |

| Justice | The fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [1]. | - Ensuring the selection of subjects is equitable and does not target vulnerable populations without justification.- Defining inclusion/exclusion criteria based on the scientific goals, not administrative convenience. |

A Structured Workflow for Risk-Benefit Assessment

A systematic assessment requires a structured, multi-step process. The diagram below outlines the key sequential steps for which investigators bear primary responsibility, leading to the IRB's ultimate determination.

Quantitative Frameworks for Benefit-Risk Assessment

While a qualitative summary of benefits and risks is common, a shift toward more quantitative approaches is occurring to enhance objectivity, transparency, and reproducibility [30]. A robust quantitative framework should be as quantitative as possible, incorporate the patient's perspective, be transparent, and be applicable throughout the drug's lifecycle [30].

Core Quantitative Metrics and Data Presentation

Systematic reviews and protocols should use an information-preserving approach, reporting absolute risks to allow for the calculation of various metrics [31]. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics used in benefit-risk assessments.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Benefit-Risk Assessment

| Metric | Description | Application & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Risk (AR) | The actual event rate in a population (e.g., events per 1,000 person-years) [31]. | Serves as the foundational data point for calculating other metrics. Must be reported for both treatment and control groups. |

| Risk Difference (RD) | The absolute difference in event rates between two groups. | Provides a direct measure of the intervention's effect size. Calculated from absolute risks. |

| Number Needed to Treat (NNT) | The number of patients needing treatment for one to benefit. NNT = 1 / RD (for benefit). | A clinically intuitive measure for benefits. A lower NNT indicates a more effective intervention. |

| Number Needed to Harm (NNH) | The number of patients needing treatment for one to be harmed. NNH = 1 / RD (for harm). | A clinically intuitive measure for risks. A higher NNH indicates a safer intervention. |

| NNT to NNH Ratio | A simple ratio comparing the metrics for a key benefit and a key harm [31]. | Provides a single quantitative value. A ratio >1 suggests benefits may outweigh the specific harm, but requires context of severity. |

An Advanced Quantitative Framework

A more sophisticated quantitative framework aims to create a true benefit-risk ratio by incorporating the severity of outcomes and the context of the disease. One proposed model uses the following equation [30]:

Benefit-Risk Ratio = (Frequency of Benefit × Severity of Disease) / (Frequency of Adverse Reaction × Severity of Adverse Reaction)