Plain Language in Informed Consent: A Strategic Guide for Clinical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing plain language in informed consent forms (ICFs).

Plain Language in Informed Consent: A Strategic Guide for Clinical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing plain language in informed consent forms (ICFs). It covers the ethical and regulatory foundations, outlines a step-by-step methodology for creating clear and accessible documents, offers solutions for common challenges, and reviews evidence validating the impact of these practices on participant comprehension and study integrity. The guidance is aligned with current regulations, including the Revised Common Rule's requirement for a concise key information section, and is designed to improve the ethical conduct and operational efficiency of clinical research.

The Why: Ethical and Regulatory Imperatives for Plain Language Consent

Informed consent serves as a cornerstone of ethical clinical research, embodying two distinct but interrelated components: the informed consent conversation (ICC) and the informed consent document (ICD) [1]. While the completed form provides essential documentation, the underlying process constitutes a comprehensive dialogue between researchers and potential participants. This process begins at the initial solicitation and continues throughout the research relationship, ending only when the participant's information or biospecimens are no longer used in research [2]. The ethical foundation rests on three core principles derived from the Belmont Report: information provision, comprehension assurance, and voluntariness of participation [3]. Effective implementation requires that consent materials be written in plain language appropriate to the subject population, typically at an 8th grade reading level or lower, to facilitate true understanding [4].

Quantitative Evidence: Document Versus Conversation

A prospective multi-site study analyzing consent processes for pediatric phase I oncology trials provides compelling quantitative evidence of the disparities between consent documents and conversations. The study transcribed and analyzed 69 unique physician-protocol pairs, comparing the word count, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL), and Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRES) of informed consent conversations against their corresponding documents [1].

Table 1: Linguistic Complexity Comparison Between Consent Documents and Conversations

| Parameter | Informed Consent Documents (ICD) | Informed Consent Conversations (ICC) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word Count | 6,364 | 4,677 | 0.0016 |

| Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) | 9.7 | 6.0 | <0.0001 |

| Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRES) | 56.7 | 77.8 | <0.0001 |

Table 2: Coverage of Critical Consent Elements During Conversations [1]

| Critical Consent Element | Percentage Discussed During ICC |

|---|---|

| Potential Side Effects | 91% |

| Study Purpose | 86% |

| Safety Mechanisms | 87% |

| Withdrawal Rights | 58% |

| Explanation of Voluntariness | 55% |

| Dosing Cohorts | 44% |

| Dose Escalation | 52% |

| Dose Limiting Toxicities | 26% |

Despite using significantly more understandable language, conversations consistently omitted elements critical to fully informed consent [1]. Investigator experience did not correlate with better coverage of these elements, suggesting that systematic approaches rather than reliance on clinical experience are needed to improve the process.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Consent Process Research

Protocol: Readability Analysis of Consent Components

This methodology details the approach used to generate the quantitative data presented in Section 2, enabling researchers to replicate similar studies in different clinical contexts [1].

Objective: To determine whether length and reading levels of transcribed Informed Consent Conversations (ICCs) are lower than their corresponding Informed Consent Documents (ICDs), and to assess whether investigator experience affects use of simpler language and comprehensiveness.

Materials and Equipment:

- Audio recording equipment

- Transcription software or services

- Microsoft Word 2010 or equivalent software with grammar check functionality

- Readability analysis tools (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Flesch Reading Ease Score)

Procedural Steps:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit families considering participation in clinical trials at multiple research centers.

- Audio Recording: Audio-record consent conversations between investigators and parents/patients eligible for studies.

- Verification: Transcribe conversations according to a predetermined transcription guide and verify by a second study team member.

- Data Segregation: Isolate investigator-spoken words, excluding questions or words spoken by patients or family members.

- Readability Analysis: Analyze transcribed conversations using grammar check software to collect: (1) word count; (2) Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL); and (3) Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRES).

- Document Analysis: Apply identical software analysis to the corresponding IRB-approved informed consent documents.

- Element Coverage Assessment: Code transcripts for coverage of 8 pre-specified critical consent elements through qualitative content analysis.

- Experience Correlation: Correlate years of investigator experience with readability scores and element coverage using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., spearman correlation coefficients, logistic regression).

Validation Method: Use paired-sign test to compare length and readability of transcribed conversations with their corresponding documents.

Protocol: Stakeholder Perception Assessment

This protocol outlines a survey-based methodology for quantifying how clinical research participants and staff experience the informed consent process, with emphasis on contextual factors [5].

Objective: To describe how participants and research staff experience the informed consent process and the contextual factors that contribute to their satisfaction.

Materials and Equipment:

- Anonymous surveys (paper and electronic versions for participants, electronic version for staff)

- Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) or equivalent data management tool

- Social media platforms and professional networks for distribution

Procedural Steps:

- Survey Design: Develop separate surveys for research participants (14 multiple choice questions) and research staff (16 multiple choice questions), each with one optional open-ended question.

- Piloting: Pilot surveys among six members of target groups and adjust wording for clarity.

- Participant Recruitment: Distribute surveys to research participants (>18 years old who have taken part in research) via clinical/research teams during routine visits and through digital marketing/social media.

- Staff Recruitment: Distribute staff surveys to those who facilitate informed consent discussions with adult participants via professional networks, newsletters, and social media.

- Data Collection: Collect responses between September 2020 and February 2021.

- Data Management: Input responses into REDCap, with manual verification of data entry accuracy for a random 20% of paper surveys.

- Analysis: Use descriptive statistics for multiple-choice questions and thematic analysis for open-ended responses.

Validation Method: Mitigate acquiescence bias through Likert scales, neutral questions, and "I can't remember" options; minimize social desirability bias by ensuring participants return surveys by post rather than to healthcare teams.

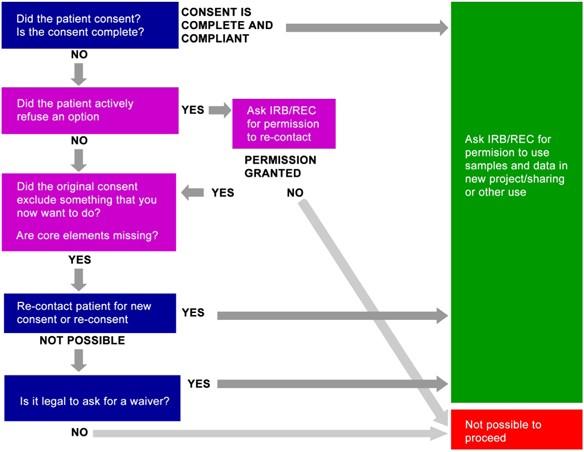

Visualizing the Informed Consent Process

The informed consent process is a multi-stage journey rather than a single event. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and their interrelationships:

This process continues throughout the research relationship, with particular importance placed on providing adequate time for the consent discussion and using techniques like Teach-Back to confirm understanding [5] [2]. Research indicates that consent forms should "begin with a concise and focused presentation of the key information" most likely to assist prospective participants in understanding reasons for or against participation [2] [3].

Research Reagent Solutions: Tools for Effective Consent Processes

Table 3: Essential Resources for Optimizing Informed Consent Processes

| Tool Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Readability Assessment | Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) | Quantifies educational grade level required to understand text [1] |

| Readability Assessment | Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRES) | Measures ease of reading (higher scores reflect easier readability) [1] |

| Regulatory Guidance | 2018 Common Rule §46.116 | Outlines federal requirements for informed consent elements [4] [6] |

| Template Resources | IRB-HSBS Informed Consent Templates | Provides standardized formats including required consent elements [4] |

| Plain Language Tools | PlainLanguage.gov | Offers guidelines for creating clear, understandable consent materials [3] |

| Process Enhancement | Teach-Back Technique | Validates participant understanding through demonstration of knowledge [2] |

| Risk Communication | NCCN Informed Consent Language Database | Provides standardized lay language descriptions of risks [6] |

| Multi-Format Platforms | Electronic Consent (eConsent) | Incorporates dictionaries, animation, videos for different learning styles [7] |

Discussion: Integrating Components for Ethical Practice

The empirical evidence demonstrates that while consent conversations use simpler language than their corresponding documents, they often omit critical elements necessary for fully informed consent [1]. This gap highlights the need for structured approaches that optimize both components of the consent process. Research staff have expressed concerns about participants' understanding of complex information, with 56% of staff worried about comprehension and 63% noting that information leaflets are too long and/or complicated [5].

Successful implementation requires allocating adequate time for consent discussions and considering contextual factors such as setting and timing [5]. The process should be recognized as beginning when potential participants are first educated about the study and continuing through the provision of study results [5] [2]. By integrating plain language principles, appropriate readability tools, and comprehension validation techniques like Teach-Back, researchers can transform informed consent from a bureaucratic hurdle into a meaningful ethical practice that truly respects participant autonomy and promotes understanding.

Application Notes: Integrating Ethical Principles into Practice

Respect for persons is a foundational ethical principle that requires acknowledging the autonomy of individuals and protecting those with diminished autonomy. In practical research terms, this principle is operationalized primarily through the informed consent process, which is more than just a signature on a document—it is a comprehensive process built on trust and respect that continues throughout the study [8] [9].

Foundational Ethical Framework

The National Institutes of Health outlines seven main principles to guide ethical research, several of which directly support respect for persons and autonomous decision-making [8]. These provide a framework for developing application notes that researchers can implement in practice.

Table: Core Ethical Principles Supporting Respect for Persons

| Ethical Principle | Definition | Application to Respect for Persons |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent | Potential participants make their own decision about participation based on comprehensive information [8]. | Cornerstone of autonomy; ensures individuals are active agents in the decision to volunteer. |

| Respect for Potential and Enrolled Subjects | Individuals treated with respect from initial approach through study completion, including respecting privacy and right to withdraw [8]. | Acknowledges ongoing autonomy throughout research participation. |

| Favorable Risk-Benefit Ratio | Everything done to minimize risks and maximize benefits for participants [8]. | Demonstrates respect for persons by protecting their well-being. |

| Fair Subject Selection | Recruitment based on scientific goals, not vulnerability or privilege [8]. | Prevents exploitation and promotes equitable respect for all persons. |

Legal and Ethical Foundations of Consent

The legal and ethical validity of consent is rooted in foundational documents including the Nuremberg Code and the Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46.116) [9]. Principle I of the Nuremberg Code states that "the voluntary consent of the human subject is essential," emphasizing that individuals must have sufficient knowledge and comprehension to make an understanding and enlightened decision [9].

For consent to be ethically and legally valid, it must meet three core requirements [9]:

- Information disclosure: Comprehensive explanation of the study purpose, activities, risks, and benefits

- Assessment of competency: Evaluation of the participant's capacity to understand and make a decision

- Voluntariness: Emphasis on the voluntary nature of the decision, free from coercion

Experimental Protocols: Validating Plain Language in Informed Consent

This protocol provides a methodology for empirically testing the effectiveness of plain language requirements in informed consent forms. The study design evaluates comprehension, autonomy perception, and satisfaction across different consent form formats.

Table: Key Variables and Measurement Instruments

| Variable Category | Specific Variables | Measurement Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Consent Form Type: Standard vs. Plain Language (8th grade) | Flesch-Kincaid Readability Score [9] |

| Dependent Variables | Comprehension Score | Study-Specific Knowledge Assessment (20 items) |

| Autonomy Perception | Modified Autonomy Preference Index (API) | |

| Decision Satisfaction | Decision Satisfaction Scale (DSS) | |

| Completion Rate | Participation Tracking Log | |

| Demographic Variables | Education level, Health literacy, Age, Prior research experience | Demographic Questionnaire |

Detailed Methodology

Phase 1: Consent Form Development

Ensure both versions contain all required consent elements [9]:

- Purpose of the study

- Study procedures, duration, and tasks

- Reasonably foreseeable risks and discomforts

- Reasonably expected benefits

- Alternative procedures available

- Confidentiality provisions

- Compensation information (if applicable)

- Contact information for questions

- Voluntary participation statement

Validate readability using Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Reading Ease formula to confirm the plain language version achieves the target 8th grade reading level [9].

Phase 2: Participant Recruitment and Randomization

- Recruit participants representing the target research population (N=400) with diverse educational backgrounds and health literacy levels.

- Randomly assign participants to one of two experimental conditions:

- Group A: Standard consent form (n=200)

- Group B: Plain language consent form (n=200)

- Obtain preliminary consent for participation in the validation study.

Phase 3: Data Collection

- Administer consent forms to respective groups in controlled settings.

- Allow sufficient time for review (minimum 30 minutes) and provide opportunity for questions.

- Administer assessment battery in the following sequence:

- Comprehension assessment (immediately after consent review)

- Autonomy Perception Index

- Decision Satisfaction Scale

- Demographic questionnaire

Phase 4: Data Analysis

- Compare mean comprehension scores between groups using independent samples t-test.

- Analyze autonomy and satisfaction scores using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA).

- Examine moderating effects of demographic variables using regression analysis.

- Calculate effect sizes for all significant differences.

Diagram: Experimental Protocol for Validating Plain Language Consent Forms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Ethical Consent Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Flesch-Kincaid Readability Formula | Quantitatively assesses reading level of consent documents; targets 8th grade level [9]. | Built into Microsoft Word; evaluates sentence length and syllable count. |

| Plain Language Templates | Pre-formatted consent templates with required ethical and regulatory elements [4]. | IRB-HSBS templates include 2018 Common Rule key information elements. |

| Short Form Consent Process | Structured approach for participants with language barriers or limited literacy [10]. | Uses interpreter, witness, and translated documents for non-English speakers. |

| Comprehension Assessment Tools | Validated instruments to measure participant understanding of consent information. | Multiple-choice questions testing key study aspects: procedures, risks, voluntary nature. |

| Informed Consent Guidelines (45 CFR 46.116) | Regulatory framework specifying required consent elements [4] [9]. | Ensures all legally mandated components are included in consent documents. |

Advanced Considerations for Vulnerable Populations

Supporting Autonomous Decision-Making in Vulnerable Groups

Research with vulnerable populations, including people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), requires additional ethical considerations. The standard approach to respecting autonomous decisions must be enhanced with demonstrated trustworthiness from healthcare providers and researchers [11].

Protocol Modifications for IDD Populations:

- Trustworthiness demonstration: Researchers must proactively establish trustworthiness before assuming capacity for autonomous decisions [11]

- Supported decision-making: Implement frameworks that acknowledge relational autonomy and provide appropriate support

- Dignity of risk: Recognize that the right to make potentially risky decisions is part of personal autonomy and self-determination [11]

Diagram: Supporting Autonomous Decision-Making in IDD Populations

Regulatory Framework and Future Directions

Evolving Standards for Protocol Development

The recently updated SPIRIT 2025 statement provides evidence-based guidance for clinical trial protocols, reflecting methodological advances and emphasizing patient-centered approaches [12]. Key updates include:

- New open science section: Enhancing transparency through trial registration, data sharing, and protocol accessibility [12]

- Patient and public involvement: Explicit requirement describing how patients will be involved in trial design, conduct, and reporting [12]

- Enhanced harm reporting: Additional emphasis on assessment and description of harms [12]

- Expanded checklist: 34 minimum items to address in trial protocols with accompanying explanation and elaboration document [12]

Implementation in Drug Development Context

For professionals in pharmaceutical development, ethical principles must be integrated throughout the clinical trial process. The abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) process demonstrates how ethical considerations are embedded in regulatory frameworks, requiring demonstration of bioequivalence while maintaining ethical standards for human subjects [13].

The evolving landscape of research ethics continues to emphasize the central importance of respect for persons through improved consent processes, enhanced transparency, and meaningful participant engagement. Implementation of these protocols and application notes will strengthen both the ethical conduct and scientific validity of research involving human subjects.

The Revised Common Rule, which took effect in 2019, represents the first significant modernization of the U.S. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects in nearly three decades [14]. These revisions aim to enhance protections for research participants while reducing unnecessary administrative burdens on investigators [15] [16]. A cornerstone of these changes involves substantial modifications to the informed consent process, with a particular emphasis on improving participant comprehension through new structural and content requirements [17].

The revisions respond to a research environment that has evolved considerably since the original Common Rule's implementation, characterized by an expansion in clinical trial types, increased use of electronic health data, and more sophisticated analytic techniques for studying biospecimens [14]. A key driver for change was documented evidence that consent forms had become excessively lengthy and complex, with one review finding that fewer than one-third of participants adequately understood critical study aspects such as goals, risks, benefits, and randomization procedures [15]. The updated regulations seek to rebalance this dynamic by making consent forms more effective tools for facilitating genuine understanding and autonomous decision-making [18] [17].

Key Regulatory Changes to the Informed Consent Process

Foundational Requirements: The "Reasonable Person" Standard and Key Information

The Revised Common Rule introduced two pivotal general requirements that fundamentally reshape how consent information must be presented to potential research participants:

The Reasonable Person Standard (45 CFR 46.116(a)(4)): Investigators must provide participants with "the information that a reasonable person would want to have in order to make an informed decision about whether to participate, and [an] opportunity to discuss that information" [16]. This standard moves beyond mere technical compliance toward a more participant-centric approach to information disclosure [17].

The Key Information Mandate (45 CFR 46.116(a)(5)): Consent must "begin with a concise and focused presentation of the key information that is most likely to assist a prospective subject or legally authorized representative in understanding the reasons why one might or might not want to participate in the research" [15] [2] [16]. This section must be organized to facilitate comprehension, representing a significant departure from the traditional approach of presenting consent information as a comprehensive list of isolated facts [17].

New and Modified Consent Form Elements

The Revised Common Rule expanded both the basic and additional elements required in informed consent documentation. These changes address evolving ethical concerns in modern research, particularly regarding biological specimens and data usage [15].

Table 1: New Consent Form Elements in the Revised Common Rule

| Element Type | Applicability | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Element | Required when research involves collection of identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens | A statement indicating whether identifiers may be removed and if the deidentified information/biospecimens may or may not be used or shared for future research [15] [16] | Addresses historical lack of transparency about secondary research uses, as exemplified by the Henrietta Lacks case [15] |

| Additional Element | Required if applicable | Statement on whether biospecimens may be used for commercial profit and if the subject will share in that profit [15] [16] | Discloses potential commercial interests that might otherwise be unknown to participants [17] |

| Additional Element | Required if applicable | Statement on whether clinically relevant research results will be returned to subjects and under what conditions [15] [16] | Clarifies distinction between clinical care and research participation [17] |

| Additional Element | Required if applicable | For research involving biospecimens, statement on whether the research will or might include whole genome sequencing [15] [16] | Informs participants about specific genetic analyses that may raise unique privacy or psychological concerns [15] |

Practical Application: Implementing the Key Information Mandate

Determining What Constitutes "Key Information"

Regulatory guidance suggests that key information should include elements most relevant to a participant's decision-making process. The Secretary's Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP) provides conceptual guidance through key questions investigators should consider when developing this critical section [2]:

Table 2: SACHRP Questions for Determining Key Information

| Question Category | Representative Questions |

|---|---|

| Participation Motivators | What are the main reasons a subject will/will not want to join this study? |

| Study Fundamentals | What research question is the study trying to answer? Why is it relevant to the subject? |

| Participant Experience | What types of activities will subjects do in the research? How will participation impact the subject outside of the research? |

| Novel Aspects | What aspects of participation are likely to be unfamiliar or diverge from expectations? |

While the regulations specify that key information "may include" elements such as voluntary participation, purpose, duration, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives, the determination ultimately requires careful consideration of what a reasonable person would need to know to make an informed decision within the specific study context [2].

Protocol for Developing Compliant Consent Forms

Objective: To create an informed consent form that complies with Revised Common Rule requirements while genuinely enhancing participant understanding.

Materials: Study protocol document, regulatory requirements checklist, plain language resources, readability assessment tools.

Procedure:

Preparatory Phase:

Content Outline Development:

Drafting Key Information Section:

- Begin with a concise statement that the activity involves research and participation is voluntary [15].

- Present purpose, expected duration, and procedures in plain language [2].

- Describe reasonably foreseeable risks and discomforts [2].

- Describe any potential benefits to participants or others [2].

- Note appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment that might be advantageous [2].

- Limit this section to approximately 1-2 pages using bullet points and white space to enhance readability.

Document Refinement:

- Apply plain language principles throughout the entire document [2] [9].

- Assess reading level using tools like Flesch-Kincaid, aiming for 8th-grade level or lower [9].

- Conduct usability testing with individuals representative of the study population [2].

- Implement teach-back methods where participants explain study elements back to research staff to confirm understanding [2].

Research Reagent Solutions for Consent Development

Table 3: Essential Resources for Developing Compliant Consent Forms

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Checklist | Tracks required consent elements under Revised Common Rule | Customize based on study type (e.g., biospecimen research requires additional elements) [15] [16] |

| Readability Software | Assesses reading level using Flesch-Kincaid or similar metrics | Target 8th-grade level or lower; check sentence length and word difficulty [9] |

| Plain Language Thesaurus | Provides alternative common words for complex medical/scientific terms | Replace "antecubital venipuncture" with "blood draw from arm" [2] |

| Usability Testing Protocol | Gathers feedback from individuals representative of study population | Identify confusing sections and improve comprehension before IRB submission [2] |

| Teach-Back Guide | Provides structured approach for research staff to confirm participant understanding | Participants explain key concepts back to staff to verify comprehension [2] |

Discussion: Implications for Research Practice

The Revised Common Rule's emphasis on key information and the reasonable person standard represents a significant shift in the ethical and regulatory approach to informed consent. Rather than treating consent as a static event focused on signature collection, the revised framework conceptualizes consent as an ongoing process centered on participant understanding [17] [9]. This approach acknowledges that merely providing information is insufficient if that information is not comprehended by those making participation decisions [17].

For researchers, these changes require more than simple template modifications. Successful implementation demands a fundamental rethinking of how consent information is structured and presented. The key information section should function as a decision aid rather than a comprehensive study description, emphasizing the most salient points that would influence a person's choice to participate [15] [2]. This approach helps address the problem of information overload, where excessive detail in traditional consent forms often obscured rather than clarified important considerations [18].

The new requirements also present ongoing implementation challenges. The "reasonable person" standard provides limited specific guidance, requiring researchers and IRBs to develop context-dependent interpretations [17]. Similarly, determining what constitutes sufficiently "key" information involves subjective judgment that may vary across study types and populations. These areas will likely evolve through regulatory guidance and practical experience as institutions share their approaches and consent forms become publicly available for certain clinical trials [17].

The Revised Common Rule's key information mandates represent a significant advancement in the ethical conduct of human subjects research. By requiring that consent forms begin with a concise, focused presentation of the most decision-critical information, the regulations aim to make informed consent more meaningful and participant-centered. Successful implementation requires researchers to thoughtfully identify and clearly communicate the factors most relevant to participation decisions, presenting this information in language and formats that facilitate genuine comprehension. When properly executed, these changes have the potential to strengthen the partnership between researchers and participants, enhancing both the ethical integrity of research and public trust in the research enterprise.

The ethical conduct of clinical research is fundamentally grounded in the principle of respect for persons, which is operationalized through the informed consent process [9]. A valid informed consent requires that participants have sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the subject matter to enable an understanding and enlightened decision [9]. However, the effectiveness of this process is critically dependent on one often-overlooked factor: health literacy. Health literacy encompasses the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions. When research informed consent forms (ICFs) are developed without health literacy principles, they can become a barrier to comprehension rather than a tool for enlightenment. This article explores the critical link between health literacy and comprehension in clinical research, providing data-driven insights and practical protocols for creating accessible informed consent materials.

Quantitative Assessment of Current Consent Form Readability

Recent empirical evidence demonstrates a significant disconnect between the language used in research ICFs and the health literacy levels of potential participants. A 2025 retrospective cross-sectional study assessed the readability of 266 health research ICFs approved by the National Health Research Ethics Committee (NatHREC) in Tanzania, providing crucial quantitative benchmarks for the field [19].

Table 1: Readability Assessment of Health Research Informed Consent Forms (n=266)

| Assessment Metric | Results | Recommended Benchmark | Compliance Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Page Count | 65.4% had recommended page numbers | ≤3 pages | Moderate |

| Sentence Length | 81.6% had longer sentences | ≤15 words per sentence | Poor |

| Readability (Flesch Reading Ease) | 80.5% were difficult to read | Score of 60-70 (Standard) | Poor |

| Reading Grade Level | Required US Grade 10 (Form Four in Tanzania) | ≤US Grade 8 | Poor |

The study employed two validated readability formulas: Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) and Flesch-Kincaid Readability Grade Level (FKRGL) [19]. Statistical analysis revealed that sentence length showed a significant correlation with difficult reading levels (p-values < 0.001 at 95% confidence level), indicating that verbose sentence construction is a primary contributor to poor comprehension [19]. These findings align with challenges observed in diverse global contexts, including Iran, the USA, Ireland, and several African nations [19].

Experimental Protocols for Readability Assessment and Improvement

Protocol 1: Readability Testing for Informed Consent Forms

Purpose: To quantitatively and qualitatively assess the readability of research ICFs using standardized metrics and human feedback.

Materials:

- ICF in editable digital format (Microsoft Word)

- Flesch-Kincaid readability software (built into Microsoft Word)

- Participant recruitment from target population

- Assessment checklist

- Structured interview guide

Methodology:

- Document Preparation: Convert ICF to Microsoft Word format. Remove all identifying information (investigator names, institutional logos) to prevent bias [19].

- Automated Readability Analysis: a. Open the document in Microsoft Word b. Navigate to File > Options > Proofing c. Select "Show readability statistics" d. Run spelling and grammar check to trigger readability report e. Record FRE and FKRGL scores, word count, and sentence length [19]

- Human Comprehension Assessment: a. Recruit 5-10 participants representative of the target research population b. Present the ICF using the planned consent process c. Administer a comprehension assessment using the teach-back method d. Conduct structured interviews to identify problematic phrases and concepts

- Data Synthesis: Combine quantitative readability scores with qualitative feedback to identify specific areas for improvement.

Validation: Compare final readability scores against benchmark of ≤8th grade reading level and FRE score of 60-70 [4] [9].

Protocol 2: Plain Language Revision of Informed Consent Forms

Purpose: To systematically transform technically complex ICFs into plain language documents that maintain regulatory compliance while enhancing comprehension.

Materials:

- Source ICF with readability assessment data

- Plain Language Checklist [20]

- Regulatory requirements checklist [2]

- Multidisciplinary team (investigator, plain language expert, community representative)

Methodology:

- Requirement Mapping: a. Create a table of all legally required consent elements per 45 CFR 46.116 [2] [4] b. Identify state-specific and industry-specific additional requirements c. Categorize elements as "key information" versus "additional information"

- Key Information Section Development:

a. Begin with a concise presentation of key information as required by the Revised Common Rule [2]

b. Structure key information using SACHRP guiding questions [2]:

- What are the main reasons a subject will want to join this study?

- What are the main reasons a subject will not want to join this study?

- How will the subject's experience differ from standard treatment?

- Plain Language Implementation: a. Apply the "Everyday Words for Public Health Communication" principles [20] b. Reduce sentence length to average 15-20 words [21] c. Use active voice and second person ("you") throughout [4] d. Organize content into logical chunks with descriptive headings [20] e. Replace technical jargon with common, everyday alternatives f. Incorporate visual elements, bullet points, and white space to improve readability

- Validation and Refinement: a. Conduct usability testing with the target population b. Use teach-back methods to verify comprehension [2] c. Obtain IRB/EC review and approval

Quality Control: Apply the Plain Language Checklist to ensure all principles have been implemented [20].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Health Literacy Implementation

| Tool Name | Source | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flesch-Kincaid Readability Formulas | Microsoft Word | Quantifies reading grade level and ease of reading | Automated initial assessment of ICF readability [19] [9] |

| Plain Language Checklist | CDC | Provides criteria for clear communication | Guiding document revision and quality assurance [20] |

| Everyday Words for Public Health Communication | CDC | Thesaurus for simplifying technical terms | Replacing jargon with common alternatives [20] |

| Informed Consent Templates | Institutional Review Boards | Regulatory-compliant ICF structure | Ensuring all required elements are included [4] |

| Teach-Back Method | Health Literacy Tools | Verbal verification of understanding | Assessing participant comprehension during consent process [2] |

The Three Pillars of Effective Consent: A Framework for Implementation

The development of literacy-appropriate consent forms requires addressing three foundational pillars: Purpose, Audience, and Process [2]. This framework ensures both regulatory compliance and genuine participant understanding.

Purpose-Driven Consent Design

Informed consent serves multiple purposes beyond regulatory compliance. Effective ICFs must simultaneously function as decision-making aids for potential participants, educational tools for research staff, ethical frameworks for IRB reviewers, and reference documents for enrolled participants [2]. This multidimensional purpose necessitates careful consideration of what information to include and how to present it clearly. The fundamental goal remains facilitating understanding to support autonomous decision-making about research participation [2].

Audience-Centered Communication Strategies

Understanding the target audience is critical for developing effective consent materials. This requires consideration of demographic factors, cultural backgrounds, medical contexts, and literacy levels [2]. Best practices include involving people from the study population during protocol and consent form development to ensure materials meet their informational needs and are designed for a study they would want to join [2]. For multicultural contexts, translation into relevant languages and adaptation of cultural references may be necessary [22].

Process-Oriented Consent Implementation

Consent is an ongoing process rather than a single form-signing event [9]. This process begins with initial study education and continues throughout the research participation period [2]. Key considerations include determining when and how participants will receive consent forms, how long they will have to review them, who will be available to answer questions, and how the consent process will support ongoing questioning and discussion [2]. The most effective processes incorporate interactive elements, particularly the evidence-based teach-back method where participants demonstrate understanding by explaining concepts in their own words [2].

Regulatory Framework and Key Information Requirements

The Revised Common Rule (2018) mandates that consent forms "begin with a concise and focused presentation of the key information that is most likely to assist a prospective subject or legally authorized representative in understanding the reasons why one might or might not want to participate in the research" [2] [4]. This regulatory requirement emphasizes the importance of foregrounding the most critical elements for decision-making.

Table 3: Key Information Elements for Informed Consent Forms

| Element Number | Required Element | Application Notes | Regulatory Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Statement that project is research and participation is voluntary | Must be explicit and prominent | 45 CFR 46.116 [4] |

| 2 | Summary of research (purpose, duration, procedures) | Focus on what participants will experience | 45 CFR 46.116 [4] |

| 3 | Reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts | Describe in specific, understandable terms | 45 CFR 46.116 [4] |

| 4 | Reasonably expected benefits | Distinguish between direct and societal benefits | 45 CFR 46.116 [4] |

| 5 | Alternative procedures or course of treatment | Primarily for clinical research | 45 CFR 46.116 [4] |

The Secretary's Advisory Committee on Human Research Protection (SACHRP) provides guiding questions to help determine what constitutes key information for specific studies, including: "What are the main reasons a subject will want to join this study?" and "What are the main reasons a subject will not want to join this study?" [2]. This approach ensures that the key information section addresses the most salient considerations for potential participants.

The critical link between health literacy and comprehension in clinical research demands systematic attention throughout the informed consent development process. Quantitative evidence demonstrates that most current consent forms exceed recommended readability levels, creating barriers to understanding [19]. By implementing structured protocols for readability assessment, applying plain language principles grounded in regulatory requirements, and adopting a comprehensive framework addressing purpose, audience, and process, researchers can develop consent materials that truly support autonomous decision-making. These approaches not only fulfill ethical obligations but also enhance research quality by ensuring participants genuinely understand what their involvement entails.

A valid informed consent process is a cornerstone of clinical research, essential for preserving respect for participant autonomy and dignity [23]. However, in specific and narrowly defined research contexts, such as emergency care and certain pragmatic trials, obtaining prospective informed consent is not always possible. For patients presenting with emergent, life-threatening conditions, the acuity of their illness and time-sensitive need for intervention often render them incapable of providing meaningful prospective consent [24] [25]. Similarly, some pragmatic trials embedded within routine healthcare systems encounter practical obstacles that make individual consent for data use or intervention impractical.

To address these challenges, regulations permitting an exception from informed consent (EFIC) or a waiver of informed consent (WIC) were established. These frameworks create a narrow pathway for ethically conducting vital research that would otherwise be impossible, while implementing robust alternative protections for participants [24] [25]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the ethical application of EFIC and WIC, framed within a broader thesis on informed consent and the critical role of plain language.

Regulatory Frameworks and Quantitative Review

The foundational regulations for EFIC and WIC were developed in 1996. EFIC is detailed in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation 21 CFR 50.24, while WIC is described in the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) regulation 45 CFR 46.101 [24] [25]. These are not interchangeable; EFIC applies specifically to FDA-regulated emergency research, whereas WIC applies to a broader category of minimal-risk research under the Common Rule.

A 20-year review of the use of these regulations provides critical quantitative insight into their application, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Twenty-Year Review of EFIC/WIC Study Characteristics (28 Completed Studies) [24] [25]

| Review Category | Findings | Frequency (n, %) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Consent Used | Exception from Informed Consent (EFIC) | 24 (86%) |

| Waiver of Informed Consent (WIC) | 4 (14%) | |

| Common Pathologies Studied | Cardiac Arrest | 10 |

| Hemorrhagic Shock | 6 | |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 5 | |

| Reported Pre-Study Requirements | FDA IND/IDE Application | 14 (50%) |

| Community Consultation | 13 (46%) | |

| Public Disclosure | 10 (36%) | |

| IRB-Requested Opt-Out Procedures | 7 (25%) |

This review highlights that while these regulations have enabled progress in treating devastating conditions, reporting of key ethical safeguards is inconsistent. Just 46% of publications explicitly justified the need for using EFIC/WIC, indicating a significant area for improvement in transparent reporting [24] [25].

Ethical Foundations and Tensions

The use of EFIC/WIC creates an inherent ethical tension between competing moral imperatives. This tension lies between the duty to respect participant autonomy and the compelling societal need to generate evidence to improve outcomes for populations with acute, life-threatening conditions [23]. In emergency obstetric and newborn care in low-resource settings, for example, this tension is acute; prohibiting research denies a vulnerable population access to potential research benefits, while enrolling without consent risks violating autonomy [23].

The ethical justification for these exceptions rests on a balance of principles:

- Beneficence: The potential to provide life-saving therapies and advance knowledge for future patients.

- Non-maleficence: The requirement to minimize risks and protect participants from harm.

- Justice: The fair inclusion of populations who suffer from acute conditions, ensuring they are not denied the benefits of research participation [23].

The diagram below illustrates the logical pathway and ethical balancing test that must be satisfied to justify a waiver or exception of consent.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing the key ethical and regulatory requirements for EFIC research.

Protocol for Community Consultation and Public Disclosure

Community consultation and public disclosure are not merely regulatory checkboxes but are fundamental processes for respecting the autonomy of the community from which participants will be enrolled.

Table 2: Protocol for Community Consultation and Public Disclosure

| Component | Objective | Detailed Methodology | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Mapping | Identify groups representing the community at risk for the medical condition. | - Review epidemiological data for the condition.- Identify patient advocacy groups, community leaders, and clinicians in the field.- Include past patients and their families. | A list of relevant organizations and leaders to engage. |

| Consultation Methods | Gather diverse perspectives on the research study's acceptability. | - Conduct public meetings/webinars.- Organize focus groups.- Deploy structured surveys (online, telephone, in-clinic).- Present the study's purpose, risks, benefits, and why EFIC is necessary. | Qualitative feedback and quantitative survey data on the perceived acceptability of the study. |

| Public Disclosure | Inform the broader community about the research. | - Issue press releases to local media.- Publish information on hospital/clinic websites and social media.- Display informational posters in relevant clinical areas (e.g., ED, ICUs). | Documentation of the methods used, materials distributed, and the reach of the disclosure. |

| Reporting to IRB/FDA | Demonstrate compliance and incorporate feedback. | - Summarize the consultation process, feedback received, and how the protocol was modified in response.- Provide copies of all disclosure materials. | A final report submitted to the overseeing IRB and, if applicable, the FDA. |

Protocol for Implementing Opt-Out Procedures

The opt-out mechanism is a critical safeguard that provides a direct avenue for individuals to refuse potential enrollment in advance, thereby preserving a element of individual choice.

Experimental Workflow:

- Opt-Out Mechanism Design: The IRB-approved mechanism must be accessible and understandable. This typically involves a dedicated 24/7 website and a toll-free telephone number. All public disclosure materials must clearly display these opt-out channels.

- Data Management System: Establish a secure, encrypted database to record individuals who opt out. The system must capture the individual's name and contact information, the date of opt-out, and a unique identifier.

- Integration with Enrollment Process: Prior to enrolling any patient under EFIC, the research team must check this secure database. The check must be documented in the study records.

- Respecting Opt-Out: If an individual is found in the database, they must not be enrolled in the study under any circumstances, even if they otherwise meet all inclusion criteria. Their clinical care will proceed with the local standard of care.

The workflow for checking and respecting an opt-out request during a potential enrollment scenario is detailed below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing and conducting trials under EFIC/WIC, the following "reagents" are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for EFIC/WIC Trials

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Specific Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FDA Guidance Document on EFIC | Provides the definitive regulatory framework for designing EFIC studies. | Used to ensure all pre-study requirements (community consultation, public disclosure, IRB oversight) are met. Essential for protocol development. |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | Provides independent ethical oversight and approval. | The IRB must be specially constituted and familiar with EFIC regulations. They review and approve the entire plan for community consultation, opt-out procedures, and the study protocol itself. |

| Community Consultation Toolkit | A structured set of materials and methods for engaging the community. | Includes survey templates, focus group guides, and presentation slides. Its function is to operationalize the ethical principle of community respect and gather meaningful feedback. |

| Secure Opt-Out Database | A dedicated, secure IT system for managing opt-out requests. | This system is critical for implementing the key safeguard of individual refusal. It must be HIPAA-compliant, accessible 24/7, and integrated into the enrollment workflow. |

| Plain Language Summary Template | A tool for creating accessible public disclosure and participant-facing materials. | Based on WHO templates that recommend a 6th-8th grade reading level [26]. Its purpose is to ensure that information about the trial is truly understandable to the public, aligning with core principles of informed consent even when consent is waived. |

Integration with Plain Language Principles

Even in research where consent is waived, the ethical obligation to communicate clearly and transparently remains paramount. The 2018 revision to the Common Rule mandates that informed consent forms begin with a "concise and focused presentation of key information" to facilitate comprehension [27]. This principle must extend to all public-facing documents in an EFIC/WIC study, including community consultation materials and public disclosure notices.

Best Practices for Plain Language in EFIC Contexts:

- Readability: Use tools like the Flesch-Kincaid test to ensure materials are written at a 6th to 8th-grade reading level [26] [28]. The World Health Organization recommends this level for participant materials [26].

- Clarity and Structure: Avoid jargon and technical terms. Use active voice, short sentences, and visual aids like timelines and flowcharts to explain study procedures [28].

- Actionability: Ensure that information about how to opt-out is presented clearly and prominently, allowing individuals to easily understand and act upon their right to refuse participation.

Emerging technologies, including Large Language Models (LLMs), show promise in automating the generation of more readable and actionable consent-related documents. One recent study demonstrated that LLM-generated consent forms significantly improved readability, understandability, and actionability scores compared to human-generated forms, without sacrificing accuracy [27]. This suggests a future where plain language is more scalably achieved, even in complex trial settings.

The regulations for exception from and waiver of informed consent provide a vital, ethically defensible pathway for conducting research in emergency and pragmatic settings where traditional consent is not feasible. The successful and ethical application of these regulations hinges on a steadfast commitment to their foundational safeguards: meaningful community consultation, transparent public disclosure, and functional opt-out mechanisms. Furthermore, integrating the principles of plain language into all public communications is not optional but a core ethical requirement, ensuring that the spirit of informed consent—respect for persons and their autonomy—is upheld even when the formal consent process is waived. As research methodologies and technologies evolve, so too must our commitment to these protective practices, ensuring that the pursuit of life-saving knowledge never outstrips our duty to protect the individuals and communities we serve.

The How: A Step-by-Step Framework for Writing and Designing Accessible Forms

A well-defined preparatory phase is the cornerstone of a valid and ethical informed consent process in clinical research. This initial step ensures that the consent is not merely a regulatory formality but a meaningful, ongoing dialogue that respects participant autonomy. For research to be ethical, participants must willingly volunteer, having been adequately informed about the study [4]. This protocol outlines the critical preparatory actions—defining the study's purpose, understanding the target audience, and designing the consent process—within the context of evolving global standards, including the ICH E6(R3) guidelines effective in 2025, which emphasize a principles-based and risk-proportionate approach [29]. Adherence to these protocols is essential for protecting participant rights, ensuring regulatory compliance, and generating reliable scientific data.

Defining the Research Purpose and Key Information

The first preparatory action is to articulate a clear and concise summary of the research that can be easily communicated to a potential participant. This involves distilling complex scientific objectives into key information that facilitates understanding and supports a decision about participation.

Regulatory Framework for Key Information

The revised Common Rule (2018) and harmonizing FDA guidance mandate that informed consent documents begin with a "concise and focused" presentation of key information [4] [30]. This section must help potential participants understand why they might or might not want to be part of a research study. The ICH E6(R3) guideline further reinforces the need for clear communication as part of its core ethical principles [29].

The Five Key Information Elements

Investigators must prepare a summary that addresses the following five core elements, which form the basis of the key information section [4]:

Table 1: Core Elements of Key Information in Informed Consent

| Element Number | Element Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A statement that the project is research and participation is voluntary. | A foundational declaration of the activity's nature and the individual's right to choose. |

| 2 | A summary of the research, including: purpose, duration, and list of procedures. | Provides a high-level overview of what the study entails and the participant's commitment. |

| 3 | Reasonable, foreseeable risks or discomforts. | Critical for a realistic understanding of potential physical, psychological, or social harms. |

| 4 | Reasonable, expected benefits. | Must clearly distinguish direct benefits to participants from benefits to society; compensation is not a benefit. |

| 5 | Alternative procedures or course of treatment, if any. | Primarily applies to clinical trials of therapeutic interventions. |

The logical flow from establishing the research context to outlining participant-specific implications can be visualized in the following workflow:

Identifying and Analyzing the Target Audience

A one-size-fits-all approach to consent is ineffective. The consent process and documents must be tailored to the specific subject population to ensure comprehension and genuine informed consent.

Audience Analysis and Plain Language

Informed consent documents must be written in plain language at a level appropriate to the subject population, generally at an 8th-grade reading level [4] [9] [31]. This requires avoiding technical jargon and using straightforward, understandable language. The use of complex scientific and medical terms should be avoided in favor of explanations the general public can understand [31]. Tools like the Hemingway Readability Checker or the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level formula can help assess the reading level of consent materials [9] [31].

Considerations for Vulnerable Populations

Certain populations are deemed vulnerable and require additional safeguards during the consent process. Researchers must identify if their study involves such groups and plan for enhanced protections [4] [9].

Table 2: Audience Analysis and Protections Planning

| Audience Category | Key Considerations | Required Protections & Adaptations |

|---|---|---|

| General Adult Population | Aim for ≤8th grade reading level; use second-person ("you") language [4] [32]. | Standard plain language principles; use of visuals/infographics to aid understanding [31]. |

| Children | Legal capacity to consent is absent; assent is required. | Must first obtain permission of parents in addition to the consent of the children [4]. |

| Cognitively Impaired Individuals | Assessment of capacity to understand and consent is needed [9]. | Consent from a legally authorized representative; assessment of capacity to consent may be required [31]. |

| Non-English Speaking Populations | Consent documents and process must be linguistically accessible. | Use of translated consent forms or a short-form consent process with an interpreter [31]. |

| Other Vulnerable Groups (e.g., prisoners, employees) | Potential for coercion or undue influence [9]. | IRB review of additional parameters for recruitment and consent to minimize perceived coercion [31]. |

The process for assessing the target audience and implementing appropriate consent strategies is outlined below:

Designing the Informed Consent Process

Informed consent is a process, not a single event centered on a signature [9]. It is built on trust and respect, spread throughout a study, beginning before data collection and continuing through the participant's involvement.

The Consent Process Workflow

The process typically involves a structured conversation, followed by documentation and ongoing engagement.

- Pre-Consent Preparation: The research team must confidently know and understand the study activities and prepare for common questions. They should allocate sufficient time for the consent conversation and be prepared to explain complex concepts in simple, culturally sensitive terms [9].

- The Initial Conversation: This is an open communication exchange free of coercion and bias. It involves discussing the key information and all required elements of consent, allowing the prospective participant ample time to ask questions [9] [31].

- Assessment of Comprehension: Researchers should check in with participants throughout the process to ensure understanding, particularly regarding risks and benefits. Techniques like the "teach-back" method, where participants explain the information back in their own words, can be highly effective [31].

- Documentation: After the conversation and once all questions are answered, the participant signs the consent form. This documentation can be a traditional written signature or an eConsent via an approved digital platform, a practice explicitly supported by the media-neutral language of ICH E6(R3) [31] [29].

- Ongoing Consent: The process continues by providing new information that arises during the trial, re-consenting participants if necessary, and continually affirming the participant's willingness to continue [9].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the Teach-Back Method

The teach-back method is a validated technique to ensure participant comprehension during the consent conversation.

- Objective: To verify the participant's understanding of key study elements, such as purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and the voluntary nature of participation.

- Materials: Informed Consent Form, protocol summary.

- Methodology:

- After explaining a key concept (e.g., the main procedures of the study), the investigator asks the participant to explain it back in their own words. Example: "To make sure I explained everything clearly, could you please tell me in your own words what you'll be asked to do during the study?"

- The investigator listens carefully for accuracy and completeness.

- If the understanding is incorrect or incomplete, the investigator re-explains the information using different, clearer language.

- Steps 1-3 are repeated until the participant demonstrates a clear understanding of the concept.

- This process is applied to all critical aspects of the study, particularly those relating to risks and the rights of a volunteer.

- Documentation: The use of the teach-back method and the general assessment of participant understanding should be noted in the study records.

Preparing a robust consent process requires leveraging specific tools and resources to ensure clarity, compliance, and participant understanding.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Consent Process Development

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Consent Template (e.g., IRB-HSBS template) | Provides a pre-formatted structure containing all required regulatory and institutional consent elements [4]. | Ensures new consent documents comply with 2018 Common Rule and institutional policy, preventing omission of critical clauses. |

| Readability Analyzer (e.g., Hemingway App, Flesch-Kincaid) | Quantitatively assesses the reading grade level of written text [9] [31]. | Used to revise and simplify consent form language to achieve the target ≤8th-grade reading level. |

| Plain Language Thesaurus (e.g., MRCT Center Toolkit) | Provides simpler, lay-language alternatives for complex scientific and medical terms [31] [6]. | Replaces jargon like "hypotension" with "low blood pressure" to improve participant comprehension. |

| Digital Health Technology (DHT) & eConsent Framework | Guides the integration of digital tools for remote consenting and data collection, as per ICH E6(R3) [31] [29] [6]. | Implmenting a REDCap eConsent framework with embedded multimedia (videos, infographics) to explain complex procedures. |

| Informed Consent Language (ICL) Database (e.g., from NCCN) | Offers standardized lay-language descriptions of risks and events common in clinical research [6]. | Drafting clear, consistent descriptions of chemotherapy side effects in an oncology trial consent form. |

Regulatory and Ethical Framework

The preparatory phase is conducted within a strict regulatory landscape. Key U.S. regulations include the HHS (45 CFR 46) and FDA (21 CFR 50) rules [4] [33] [32]. A significant development for 2025 is the harmonization between FDA and OHRP (Office for Human Research Protections) guidance on the requirement for a "key information" section, which aligns standards for federally funded and drug/device trials [30]. Ethically, the process is grounded in the Belmont Report principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice, requiring researchers to ensure participation is voluntary and informed, without exculpatory language [9] [32]. The upcoming ICH E6(R3) guideline reinforces these principles, promoting a flexible, quality-focused approach adaptable to diverse trial designs and technologies [29].

Regulatory Framework and Essential Elements

Informed consent is a foundational ethical and regulatory requirement in human subjects research. The process involves providing potential participants with key information about a study to enable a voluntary decision on whether to participate [34]. The following table summarizes the core elements required by major U.S. regulatory bodies.

Table 1: Essential Elements of Informed Consent per U.S. Regulations

| Element Description | Common Rule (45 CFR 46) [35] | FDA Regulations (21 CFR 50) [35] | Plain Language Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statement that study involves research | Required | Required | Clearly state "This is a research study." |

| Explanation of study purpose | Required | Required | Explain why the research is being done in 1-2 sentences. |

| Description of procedures | Required | Required | List all procedures in order, using common terms. |

| Description of foreseeable risks | Required | Required | Group risks by likelihood and severity; use descriptive scales. |

| Description of any benefits | Required | Required | Differentiate between direct benefits to participants and societal benefits. |

| Disclosure of alternative procedures | Required | Required | List standard treatments available outside the study. |

| Description of confidentiality | Required | Required | Explain who will see the information and how it will be protected. |

| Explanation of compensation | Required for > Minimal Risk | Required for > Minimal Risk | State clearly if no compensation is provided for injury. |

| Contact information for questions | Required | Required | Provide names and phone numbers of key contacts. |

| Statement that participation is voluntary | Required | Required | Use explicit language: "Your participation in this study is completely voluntary." |

Experimental Protocol for Informed Consent Document Development

Protocol: Systematic Development of a Plain Language Consent Form

Objective: To create a legally compliant informed consent document that is understandable to participants at an 8th-grade reading level.

Materials:

- Regulatory templates (e.g., from institutional IRB library) [34]

- Word processing software with Flesch-Kincaid readability tool

- 12-point Arial or Times New Roman font

Methodology:

- Template Selection: Obtain and utilize the most current IRB-approved consent form template from your institution's repository to ensure all structural elements are present [34].

- Content Drafting: Insert study-specific information into the template using complete sentences. Adhere to the following guidelines:

- Use short, simple, and direct sentences.

- Spell out all abbreviations and acronyms upon first use.

- Avoid technical jargon and scientific terms. If necessary, define them in simple language [34].

- Readability Assessment: Utilize the Flesch-Kincaid readability tool within your word processor to measure the document's grade level. Refine the language until an 8th-grade reading level is achieved [34].

- Formatting and Layout:

- Maintain a 12-point or larger font size.

- Ensure adequate white space and clear section headings.

- Use line numbers during the review process, which should be removed after IRB approval [34].

- Regulatory Review and Approval: Submit the drafted consent document to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for review and approval before use in any participant enrollment [35].

Experimental Protocol for Consent Process Assessment and Validation

Protocol: Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment of Consent Comprehension

Objective: To evaluate participant understanding of the informed consent document and process through mixed-methods analysis.

Materials:

- Approved informed consent document

- Digital data collection platform (e.g., survey host)

- Consent comprehension questionnaire

- Secure data storage system

Methodology:

- Participant Enrollment: Recruit participants according to the study's IRB-approved protocol.

- Consent Process: Conduct the informed consent process as approved by the IRB.

- Data Collection:

- Quantitative Data: Administer a structured comprehension questionnaire post-consent. The questionnaire should use multiple-choice and true/false questions to assess understanding of key study elements (e.g., purpose, procedures, risks, rights) [36].

- Qualitative Data: For a subset of participants, conduct brief, semi-structured interviews or solicit open-ended feedback to gather in-depth context on the clarity of the consent document and identify any persistent areas of confusion [36].

- Data Analysis:

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate cumulative comprehension scores and item-specific correct response rates. Summarize data using descriptive statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations, percentages) [36].

- Qualitative Analysis: Transcribe and code interview responses. Identify common themes and specific phrases or concepts that participants found unclear [36].

- Iterative Refinement: Use the combined quantitative and qualitative findings to revise and improve the consent document and process, submitting changes to the IRB for approval as necessary.

Table 2: Data Collection and Analysis Matrix for Consent Comprehension

| Data Type | Collection Method | Metric | Analysis Technique | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Comprehension Questionnaire | Correct Response Rate (%) | Descriptive Statistics (Mean, SD) | Identifies gaps in understanding of key facts [36]. |

| Quantitative | Comprehension Questionnaire | Total Comprehension Score | Descriptive Statistics (Mean, SD) | Provides an overall measure of document effectiveness [36]. |

| Qualitative | Semi-structured Interviews | Participant Quotes & Feedback | Thematic Analysis & Coding | Reveals reasons behind misunderstandings and context for numerical data [36]. |

| Integrated | Combined Quantitative & Qualitative | Points of Convergence/Divergence | Comparative Analysis | Creates a unified report for actionable revisions, telling the complete story of comprehension [36]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Informed Consent Process and Documentation

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| IRB-Approved Consent Template | Provides a pre-formatted structure that includes all required regulatory elements, streamlining document creation and ensuring compliance [34]. |

| Readability Assessment Software | Objectively measures the grade level of written text to enforce plain language standards (e.g., targeting an 8th-grade reading level) [34]. |

| Electronic Signature System | Enables remote consenting and provides a legally valid method for obtaining and documenting participant consent electronically [34]. |

| Debriefing Script Template | Provides a standardized framework for explaining any deception or incomplete disclosure used in the study and for informing participants of their data rights post-study [34]. |

| Data Anonymization Toolset | Software or procedures used to remove or code personal identifiers from research data, fulfilling confidentiality promises made in the consent document [35]. |

Visualization of Informed Consent Development Workflow

The use of plain language in informed consent forms (ICFs) is an ethical and practical imperative in clinical research. Effective communication ensures that participants fully comprehend the nature of the research, potential risks and benefits, and their rights, thereby enabling truly informed decision-making. Jargon—specialized technical language familiar only to experts—creates a significant barrier to understanding for research participants. Federal guidelines stipulate that language in ICFs should be comprehensible to subjects at the 8th-grade reading level [37]. This application note provides a structured framework for researchers to systematically identify and replace jargon with simple, clear alternatives, enhancing participant understanding and upholding the ethical standards of the informed consent process. Studies demonstrate that improving the readability of ICFs significantly increases participant comprehension and satisfaction [38].

Quantitative Data Presentation: Jargon and Plain Language Equivalents

The following tables provide a structured reference for replacing common jargon terms with their plain language equivalents, categorized for easy application.

Table 1: General Medical and Procedural Jargon

| Jargon Term | Plain Language Alternative | Rationale for Replacement |

|---|---|---|

| Abrasion | Scraped skin/area where skin is scraped away [37] | Uses concrete, familiar words. |

| Acute | New, recent, or sudden [37] | Avoids clinical ambiguity. |

| Adverse Effect | Unwanted effect [37] | Simpler, more direct terminology. |

| Analgesic | Drug used to control pain [37] | Defines the term by its function. |

| Benign | Not cancer, usually without serious consequences [37] | Provides context and reassurance. |

| Bilateral | On both sides of the body [37] | Clear anatomical description. |

| Biopsy | Removing a small piece of tissue for lab testing [37] | Describes the action and purpose. |

| Chronic | Lasting a long time [37] | Contrasts clearly with "acute." |

| Contusion | Bruise [37] | Uses a common, everyday word. |

| Edema | Swelling from fluid build-up [37] | Describes the visible condition. |

Table 2: Research-Specific and Statistical Jargon

| Jargon Term | Plain Language Alternative | Rationale for Replacement |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial | A research study with patients [37] | Clarifies the nature of the activity. |

| Control | A standard treatment or procedure used for comparison [37] | Explains the concept of comparison. |

| Contraindications | Medical reasons that prevent you from using a certain drug [37] | Focuses on patient applicability. |

| Double-blind trial | A study where neither you nor the research staff know which treatment you are receiving [37] | Explains the mechanism simply. |

| Efficacy | How well something works [37] | A succinct, clear alternative. |

| Randomization | You will be put into a study group by chance, like flipping a coin [37] | Uses a familiar analogy. |

| Informed Consent | A process to learn about the study and agree to take part [38] | Defines the process in active terms. |

Experimental Protocol: Readability Assessment and Jargon Replacement Workflow

This protocol outlines a systematic, step-by-step methodology for evaluating and revising an informed consent form to improve its readability by removing jargon and simplifying language.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Readability Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Original Informed Consent Form | The document to be analyzed and revised. |

| Digital Text File (.docx, .txt) | For software-based readability analysis. |

| Readability Assessment Software | Automated tools to calculate readability scores and identify complex language. |

| Validated Plain Language Glossary | A reference for replacing jargon with simple terms [37]. |

| Style Guide | A guide for using active voice and short sentences. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initial Readability Assessment:

- Create a digital copy of the ICF text, removing any personal identifiers.

- Input the text into readability analysis software.

- Record the initial readability scores, including Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, sentence length, and syllable count. The initial analysis of a sample form may indicate it is suitable only for persons with a university degree [38].

Jargon Identification and Replacement:

- Perform a manual review of the ICF, highlighting all technical and medical jargon.

- Cross-reference each identified jargon term with a validated plain language glossary [37].

- Systematically replace each jargon term with its plain language equivalent, as detailed in Table 1 and Table 2.

Structural and Syntactic Simplification:

- Break down long, complex sentences into shorter ones (aim for ≤ 15 words).

- Change passive voice constructions to active voice (e.g., "You will be given..." instead of "The drug will be administered to you...").

- Use second-person pronouns ("you") to address the participant directly [38].

- Ensure the document uses a logical flow with clear headings and bullet points.

Post-Revision Readability Assessment: