Navigating the Methodological Landscape: A Comparative Study of Empirical Bioethics Approaches for Biomedical Research

This article provides a systematic comparison of empirical bioethics methodologies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Navigating the Methodological Landscape: A Comparative Study of Empirical Bioethics Approaches for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of empirical bioethics methodologies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational theories and historical context of the field, details specific methodological approaches for integrating empirical data with normative analysis, addresses common challenges and proposes solutions for rigorous research, and validates findings through established standards and emerging trends. The content synthesizes current scholarly consensus and empirical research to offer a practical guide for designing, implementing, and evaluating robust empirical bioethics studies in biomedical contexts.

Understanding the Empirical Bioethics Terrain: History, Definitions, and Core Debates

The field of bioethics has undergone a significant transformation over recent decades, marked by a pronounced "empirical turn" that integrates social science research methods into traditionally normative inquiry [1]. This shift represents a movement from abstract philosophical reasoning toward engaged research that addresses practical ethical questions in healthcare and medicine [1]. The empirical turn gained momentum due to several factors: dissatisfaction with the abstract nature of theoretical bioethics, increasing engagement with clinical ethics practice, and the growing prominence of evidence-based medicine in the 1990s [1].

Empirical bioethics can be understood as research that "collects and analyses empirical data" to inform bioethical questions [1]. This approach recognizes that ethical analysis must be grounded in the actual experiences, values, and contexts of those affected by biomedical advancements [2]. The fundamental role of empirical research in bioethics resides in its potential to "inform abstract principles into workable practices and its capacity to ensure that bioethicists are in touch with the actual experiences of those affected" [1]. This methodological evolution has created a vibrant interdisciplinary field that combines normative ethical analysis with empirical investigation of real-world ethical practices and challenges.

Quantitative Landscape: Measuring the Empirical Turn

Growth of Empirical Research in Bioethics Journals

The increasing dominance of empirical approaches in bioethics is clearly demonstrated through quantitative analysis of publications in leading journals. A comprehensive review of nine major bioethics journals from 2004 to 2015 provides compelling evidence of this trend [1].

Table 1: Empirical Publications in Bioethics Journals (2004-2015)

| Journal | Total Original Papers | Empirical Papers | Percentage Empirical | Dominant Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Medical Ethics | 2,150 | 540 | 25.1% | Quantitative |

| Nursing Ethics | 1,023 | 360 | 35.2% | Qualitative |

| Bioethics | 587 | 45 | 7.7% | Mixed Methods |

| Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics | 412 | 22 | 5.3% | Mixed Methods |

| Hastings Center Report | 478 | 18 | 3.8% | Qualitative |

| Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics | 392 | 12 | 3.1% | Mixed Methods |

| Journal of Clinical Ethics | 285 | 8 | 2.8% | Qualitative |

| Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal | 140 | 1 | 0.7% | Qualitative |

| Christian Bioethics | 100 | 1 | 1.0% | Qualitative |

| Total/Average | 5,567 | 1,007 | 18.1% | Varies by Journal |

The data reveals that empirical work constituted 18.1% of all original publications across these nine bioethics journals during this period [1]. This represents a significant increase from the 1990-2003 period, when only 10.8% of articles used empirical designs [1]. The growing volume is mainly attributable to two journals: Journal of Medical Ethics and Nursing Ethics, which together accounted for 89.4% of all empirical papers published in these venues [1]. The analysis also reveals distinct methodological preferences, with Journal of Medical Ethics publishing significantly more quantitative papers, while Nursing Ethics favored qualitative approaches [1].

Expanding Scope of Empirical Bioethics

The empirical turn encompasses more than just a quantitative increase in publications; it represents a fundamental expansion of how bioethical inquiry is conducted. Empirical bioethics research now addresses a wide spectrum of objectives, from understanding the context of bioethical issues to developing and justifying moral principles [2]. A qualitative exploration of researchers' views identified a continuum of acceptable objectives for empirical research in bioethics (ERiB), ranging from modest to highly ambitious aims [2].

Table 2: Researcher Perspectives on Acceptable Objectives for Empirical Bioethics

| Objective | Acceptance Level | Key Rationales |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding the context of a bioethical issue | Unanimous agreement | Provides essential grounding for normative analysis |

| Identifying ethical issues in practice | Unanimous agreement | Reveals real-world ethical challenges |

| Describing stakeholder attitudes and behaviors | High agreement | Documents actual moral views and practices |

| Evaluating how ethical recommendations work in practice | High agreement | Tests implementation and practical impact |

| Informing policy development | Moderate agreement | Connects research to practical application |

| Recommending changes to specific ethical norms | Moderate agreement | Uses data to refine specific guidelines |

| Developing and justifying moral principles | Contested | Faces philosophical challenges (e.g., is-ought gap) |

| Using empirical research as a source of morality | Contested | Raises fundamental methodological concerns |

Researchers largely agreed that understanding context and identifying ethical issues in practice were fundamental objectives for empirical bioethics [2]. However, more ambitious goals—particularly using empirical research to develop and justify moral principles—generated significant debate [2]. The is-ought gap was not considered an absolute obstacle to ERiB, but rather "a warning sign to critically reflect on the normative implications of empirical results" [2].

Methodological Approaches: Comparative Analysis

Typology of Empirical Bioethics Methodologies

The field of empirical bioethics has developed diverse methodological approaches to integrate empirical research with normative analysis. These approaches vary in their epistemological foundations, methods of integration, and intended outcomes.

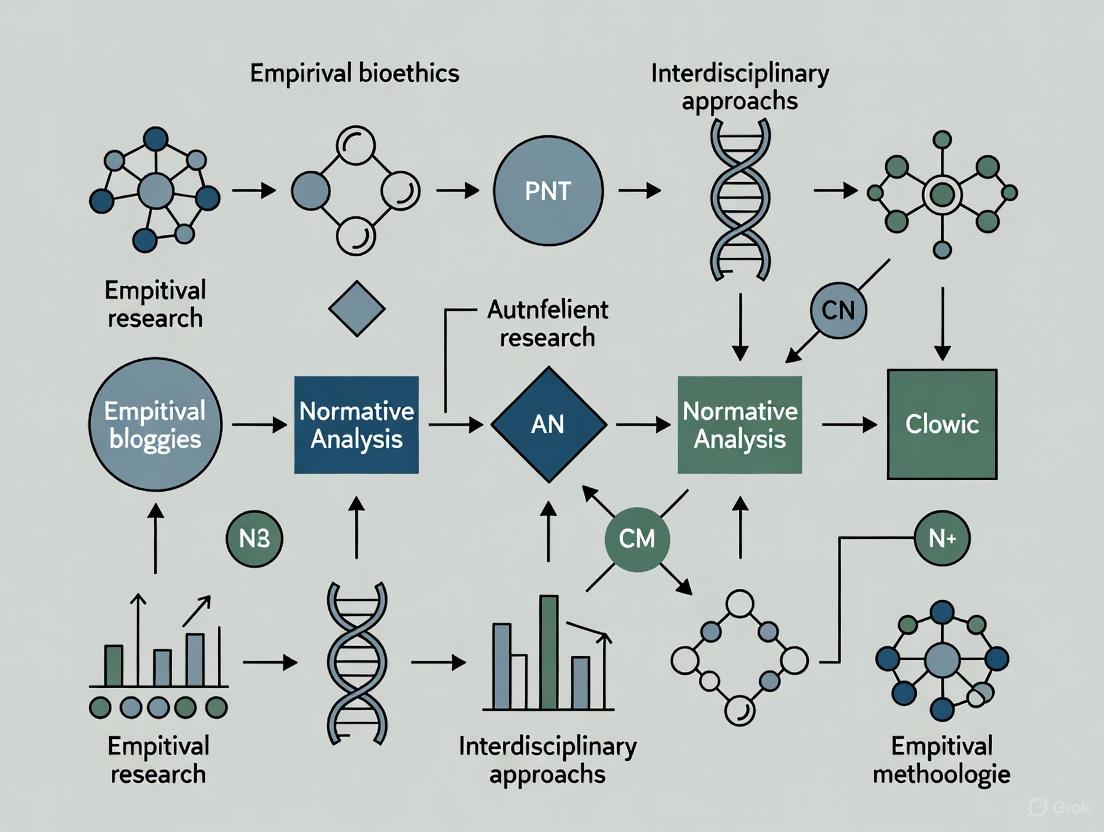

Diagram 1: Empirical Bioethics Methodological Approaches

The Principle-Based Empirically Grounded Roadmap Approach (PERA)

A recent methodological innovation in empirical bioethics is the Principle-Based Empirically Grounded Roadmap Approach (PERA), developed specifically for addressing ethical challenges in digital mental healthcare technologies [3]. PERA represents an advanced integrated methodology that responds to the unique characteristics of technology development contexts where the technological design is largely predetermined and features embedded co-development practices [3].

The PERA methodology involves three core components: (1) mapping principles from ethics literature, (2) conducting a scoping review of moral intuitions among technology developers, and (3) collecting original empirical data on specific use cases [3]. These elements are synthesized using abductive reasoning to produce a tangible output—an ethics roadmap designed to guide future iterations of the technology [3]. This approach advances empirical bioethics methodology by providing both practical tools for ethics researchers in technology projects and a means to generate empirically grounded conceptual contributions [3].

"Big Bioethics" and Large-Scale Approaches

A more recent development in the field is the emergence of "Big Bioethics," which leverages large-scale datasets to examine ethical questions [4]. This approach involves empirical bioethics research—often surveys or retrospective reviews of patient outcomes—that collect and analyze data from very large numbers of people, typically involving several thousand individuals [4]. Such studies have the statistical power to examine subtle differences in psychosocial and behavioral outcomes between subgroups, including historically underrepresented populations [4].

"Big Bioethics" represents a response to the increasing scale of translational research in healthcare and the growing availability of large datasets [4]. This approach enables researchers to identify atypical patient experiences and less common ethical perspectives that might go undetected in smaller qualitative studies [4]. However, the adoption of "Big Bioethics" also raises challenges, including the need for specialized methodological expertise and concerns about maintaining the field's commitment to understanding marginalized perspectives, which has traditionally been associated with qualitative approaches [4].

"Hidden" Empirical Bioethics

An important methodological consideration in empirical bioethics is the recognition that much ethically relevant empirical research remains "hidden" from the view of bioethicists [5]. Studies that provide data directly relevant to bioethical issues often appear in non-ethics journals, are published by professionals who do not identify as ethicists, and lack ethics-related keywords [5]. One analysis found that less than 50% of such articles discussed the ethical implications of their findings, and only a small minority contained keywords clearly related to research ethics [5].

This "hidden" empirical bioethics poses challenges for the field, as valuable data remains inaccessible to ethicists who may not encounter it through conventional literature searches in bioethics venues [5]. Addressing this problem requires encouraging researchers in other fields, editors, and database indexers to add ethics-related keywords when data are highly relevant to ethical debates, and training ethicists to search for relevant data using non-ethics terms [5].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Essential Methodological Tools for Empirical Bioethics

Conducting rigorous empirical bioethics research requires specific methodological approaches and tools. The field draws on diverse disciplinary traditions, each contributing essential research reagents to the interdisciplinary enterprise.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Empirical Bioethics

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Interview Protocols | Elicit detailed stakeholder perspectives | Understanding lived experience of ethical issues |

| Systematic Scoping Reviews | Map existing literature and identify gaps | Preliminary stage of PERA methodology |

| Validated Survey Instruments | Quantify attitudes, beliefs, behaviors | Large-scale "Big Bioethics" studies |

| Mixed-Methods Designs | Integrate qualitative and quantitative approaches | Comprehensive analysis of complex ethical issues |

| Abductive Reasoning Frameworks | Generate best explanations from incomplete data | PERA methodology for developing ethics roadmaps |

| Interdisciplinary Team Structures | Combine normative and empirical expertise | All integrated empirical bioethics research |

| Ethical Framework Analysis | Connect empirical findings to normative principles | Normative analysis of empirical data |

| Large-Scale Dataset Analytics | Identify patterns across diverse populations | "Big Bioethics" approaches with statistical power |

Integrated Research Workflow

The implementation of empirical bioethics research typically follows a structured workflow that integrates normative and empirical components throughout the research process. The following diagram illustrates this integrative approach:

Diagram 2: Empirical Bioethics Research Workflow

Current Debates and Future Directions

Methodological Tensions and Integration Challenges

The empirical turn in bioethics continues to generate important methodological debates regarding how empirical and normative dimensions should relate to one another. A central tension concerns the "is-ought" problem—the philosophical challenge of deriving normative conclusions from empirical facts [2]. While bioethicists generally agree that empirical research can inform ethical analysis, there is less consensus about how directly empirical findings should shape normative conclusions [2].

Researchers have proposed various approaches to integration, but "there is no consensus as to how this integration ought to manifest" [1]. Some scholars advocate for more ambitious integration, where empirical research directly contributes to developing and justifying moral principles [2]. Others maintain a more modest view, seeing empirical research as primarily providing context and identifying practical ethical issues without directly determining normative conclusions [2]. This tension reflects broader debates about the proper goals and methods of bioethics as an interdisciplinary field.

Emerging Trends and Training Initiatives

The field of empirical bioethics continues to evolve, with several emerging trends shaping its future direction. There is growing recognition of the need for "big bioethics" approaches that can keep pace with the scale of contemporary biomedical research [4]. Simultaneously, methodological innovation continues, as exemplified by the development of the PERA framework for digital mental health technologies [3].

Training initiatives have emerged to support the development of empirical bioethics expertise. The Empirical Bioethics Summer School, for instance, provides beginner/intermediate level training for researchers with some familiarity with empirical bioethics [6]. This four-day program covers key topics including: understanding what empirical bioethics is and exploring typologies; designing empirical bioethics research projects; methodological approaches to integration; and addressing challenges in the field [6]. Such training opportunities reflect the ongoing professionalization of empirical bioethics as a distinct subfield with its own methodologies, vocabulary, and standards of excellence.

The field also continues to grapple with practical challenges, including the inconsistent adoption of policies regarding artificial intelligence in bioethics publishing [7] and the need to ensure that empirical bioethics research maintains its commitment to giving voice to marginalized perspectives while embracing new methodological opportunities [4]. As empirical bioethics matures, these debates and innovations will likely continue to shape its development as an interdisciplinary field that bridges the normative and the empirical.

The Social Science Critique: Challenging the Foundations of Traditional Bioethics

The emergence of empirical bioethics in the early 21st century represented a direct response to mounting criticism from social scientists who questioned the foundations and methodology of traditional philosophical bioethics. This critique fundamentally challenged bioethics' self-understanding and its approach to real-world ethical problems.

Social scientists argued that traditional bioethics suffered from several critical limitations. It often privileged idealized, rational thought while tending to exclude or marginalize social and cultural factors, treating them as irrelevant to ethical analysis [8]. This approach resulted in ethical frameworks that were abstract and disconnected from the lived moral experiences of patients, families, and healthcare professionals [8] [9]. Furthermore, traditional bioethics implicitly assumed that social reality divided neatly along the same categories as philosophical theories, failing to recognize the complex, contextual nature of moral problems in healthcare settings [8].

This critique demanded a fundamental reorientation of bioethical inquiry—one that would root ethical analyses in the empirical reality of healthcare practices and moral experiences [8]. The call was for bioethics to become more self-critical, skeptical of claims made by scientists and clinicians, and rigorously engaged with the actual contexts in which ethical dilemmas arise [8]. This foundational critique set the stage for the development of more empirically-grounded approaches to bioethics.

The Empirical Turn: Quantitative Evidence of a Shifting Field

The theoretical critique of traditional bioethics coincided with a measurable shift in publication patterns within leading bioethics journals. Empirical research began to claim an increasingly significant place in bioethical scholarship, marking what came to be known as "the empirical turn" in bioethics [10] [9].

Table 1: Growth of Empirical Research in Bioethics Journals (1990-2003)

| Time Period | Total Publications | Empirical Studies | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990-1996 | 1,857 | 126 | 6.8% |

| 1997-2003 | 2,172 | 309 | 14.2% |

| Overall (1990-2003) | 4,029 | 435 | 10.8% |

Source: Borry et al. (2006) analysis of nine peer-reviewed bioethics journals [10]

This quantitative analysis of nine major bioethics journals revealed a statistically significant increase (χ² = 49.0264, p<.0001) in empirical research publications between 1990 and 2003 [10]. The proportion of empirical studies grew from just 5.4% in 1990 to 15.4% in 2003, demonstrating a clear trend toward empirical approaches [10]. The distribution of this research was uneven across journals, with Nursing Ethics (39.5%), Journal of Medical Ethics (16.8%), and Journal of Clinical Ethics (15.4%) publishing the highest percentages of empirical studies [10].

Methodologically, early empirical bioethics was dominated by quantitative approaches (64.6%), though qualitative methods were also recognized as particularly valuable for understanding values, personal perspectives, and contextual circumstances [10]. The main topics of empirical research reflected pressing clinical concerns, with prolongation of life and euthanasia being the most frequently studied subject [10].

Classifying Empirical Bioethics Research: A Hierarchical Framework

As empirical bioethics developed, scholars proposed various frameworks to categorize and understand the diverse ways in which empirical research could contribute to bioethical inquiry. One influential framework proposed four hierarchical categories that represent increasing levels of normative ambition [11].

Table 2: Hierarchy of Empirical Bioethics Research

| Category | Primary Question | Examples | Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lay of the Land | "What are current practices, opinions, or beliefs?" | Attitudes toward end-of-life care; Ethics committee composition surveys [11] | Quantitative surveys; Qualitative interviews |

| Ideal vs. Reality | "How well does practice match our ethical ideals?" | Racial disparities in healthcare; Informed consent comprehension studies [11] | Comparative analysis; Outcome studies |

| Improving Care | "How can we bring practice closer to ethical ideals?" | Interventions to reduce disparities; Consent process improvements [11] | Intervention studies; Quality improvement research |

| Changing Ethical Norms | "Should our ethical ideals change based on evidence?" | Using multiple empirical studies to question existing norms [11] | Synthesis of multiple empirical studies |

This framework demonstrates how empirical research in bioethics ranges from primarily descriptive studies that map the current ethical landscape to more ambitious normative projects that seek to refine or revise ethical norms based on empirical findings [11]. The hierarchy reflects increasing complexity in the relationship between empirical data and normative conclusions, with the highest level involving the use of cumulative empirical evidence to potentially transform ethical frameworks themselves.

Researcher Perspectives on Appropriate Objectives

A recent qualitative study exploring the views of bioethics researchers themselves reveals how those actively working in the field perceive the appropriate objectives for empirical bioethics research [2]. This research provides crucial insight into how the theoretical debate about empirical bioethics has been internalized and interpreted by practicing scholars.

Researchers expressed strongest agreement with objectives focused on "understanding the context of a bioethical issue" and "identifying ethical issues in practice" [2]. These objectives were seen as relatively uncontroversial and clearly valuable. More ambitious objectives—particularly "striving to draw normative recommendations" and "developing and justifying moral principles"—generated significantly more disagreement and debate among researchers [2].

The classical philosophical problem of the is-ought gap (the challenge of deriving normative conclusions from purely descriptive premises) was not generally seen as an insurmountable barrier to empirical bioethics [2]. Rather, researchers treated it as an important caution—a reason to engage in critical reflection about the normative implications of empirical results [2]. There was recognition that while empirical data alone cannot determine ethical conclusions, it can provide an essential "testing ground" for elements of normative theory [2].

Methodological Approaches: From Multi-Disciplinarity to Interdisciplinarity

The development of empirical bioethics has involved ongoing methodological innovation and reflection. Early approaches often simply combined empirical methods with ethical analysis, but more sophisticated methodologies have emerged that seek to truly integrate empirical and normative approaches [9].

Key Methodological Frameworks

Reflexive Balancing: This approach, proposed by Ives (2014), emphasizes the need for continuous reflection and adjustment between empirical findings and normative frameworks [9]. It acknowledges that both empirical research and ethical analysis require iterative refinement when brought into conversation with each other.

Critical Bioethics: Building on the social science critique, this approach maintains skepticism toward claims made by scientists and clinicians while insisting that ethical analyses must be rooted in empirical research [8]. It aims to produce "rigorous normative analysis of lived moral experience" rather than abstract ethical theorizing [8].

Feminist Epistemologies: These approaches actively resist strict divisions between empirical and normative inquiry, treating them as co-constitutive and intertwined [9]. This perspective has made significant contributions to empirical bioethics theory and methodology by challenging binary thinking about facts and values [9].

Experimental Protocol Template for Empirical Bioethics

Recent methodological development has focused on creating standardized approaches to empirical bioethics research. One team has formalized a protocol template suitable for all types of humanities and social sciences investigations in health, including empirical bioethics [12]. This template adapts and modifies the "Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)" to render it suitable for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method approaches in bioethics [12]. The template helps researchers structure their inquiries to ensure both empirical rigor and normative relevance.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

Conducting rigorous empirical bioethics research requires specific methodological "reagents" – essential approaches and tools that facilitate the integration of empirical and normative analysis.

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Interview Protocols | Explore lived experiences and moral reasoning of stakeholders | Understanding patient experiences in clinical trials as treatment [13] |

| Standardized Protocol Templates | Ensure methodological rigor and comprehensive reporting | Health research protocols template for empirical bioethics [12] |

| Mixed-Method Research Designs | Combine quantitative and qualitative approaches for comprehensive understanding | Studying both prevalence and experiences of ethical issues [10] [2] |

| Reflexive Balancing Framework | Systematically navigate between empirical findings and normative theory | Methodological approach for interdisciplinary bioethics [9] |

| Empirical Bioethics Taxonomy | Classify different types and purposes of empirical bioethics research | Categorizing studies from descriptive to normative [11] |

Signaling Pathways: The Logical Structure of Empirical Bioethics

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway through which the social science critique transformed traditional bioethics and stimulated the development of empirical approaches.

Conceptual Pathway from Critique to Empirical Bioethics

Current Applications and Future Directions

Empirical bioethics continues to evolve and address emerging ethical challenges in healthcare and biotechnology. Its approaches are particularly valuable for navigating novel ethical terrain where traditional ethical frameworks provide limited guidance.

Application to Emerging Technologies

The ongoing development of organ-on-a-chip technology demonstrates how empirical bioethics approaches are applied to emerging biotechnologies [14]. These microdevices that emulate human organs using human cells present novel ethical questions that benefit from empirically-informed analysis. Research in this area examines ethical considerations related to informed consent, community engagement, and personalized medicine models using patient-derived cells [14]. These analyses draw on empirical data about public attitudes, stakeholder perspectives, and actual laboratory practices to develop ethically robust guidance.

Interdisciplinary Integration

The future of empirical bioethics appears to be moving toward deeper interdisciplinary integration rather than simple multidisciplinary cooperation [9]. This involves dissolving the traditional empirical/normative divide and developing approaches that treat facts and values as co-constitutive rather than separate domains [9]. This deeper integration requires researchers to develop collaborative relationships that enable interdisciplinary critique and methodological innovation [9].

The field continues to grapple with challenges of methodological rigor and epistemic authority when working across traditional disciplinary boundaries [9]. However, the continued development of specialized training opportunities, such as the Empirical Bioethics Summer School [6], indicates the ongoing institutionalization and professionalization of this interdisciplinary field.

The emergence and development of empirical bioethics represents a fundamental transformation in how bioethics conceptualizes its subject matter and methodologies. Arising in response to powerful social science critiques of traditional approaches, empirical bioethics has established itself as a rigorous interdisciplinary field that systematically integrates empirical research with normative analysis. While tensions remain between different epistemological approaches and disciplinary orientations, the field has developed sophisticated methodologies and conceptual frameworks for addressing complex ethical problems in healthcare and biotechnology. As novel ethical challenges continue to emerge in biomedical research and clinical practice, empirical bioethics provides essential tools for developing ethically robust, empirically-informed responses.

Empirical bioethics has emerged as a critical interdisciplinary field that bridges philosophical inquiry with social science research methods to address complex ethical questions in healthcare and medicine. This field underwent a significant 'empirical turn' several decades ago in response to critiques that traditional bioethics had failed to adequately account for social context and lived experience [15]. Within this evolved landscape, two distinct methodological approaches have gained prominence: the consultative approach and the dialogical approach. These methodologies represent different poles on a spectrum of how empirical data and ethical analysis are integrated, each with distinct philosophical foundations, research processes, and applications. Understanding this spectrum is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who must navigate methodological choices in addressing ethical challenges in healthcare innovation and clinical practice.

The consultative approach typically treats empirical data as input for ethical analysis conducted primarily by researchers, while the dialogical approach emphasizes mutual understanding and co-construction of knowledge through dialogue between researchers and participants [16]. As the field continues to evolve, some scholars are now advocating for a 'theoretical turn' that encourages more deliberate integration of empirical research with philosophical theory [15]. This comparative guide examines these methodological poles through their theoretical foundations, practical applications, and relative strengths, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for methodological selection in empirical bioethics research.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Consultative Approach

The consultative approach represents a more traditional model of empirical bioethics where researchers primarily maintain control over the ethical analysis while consulting stakeholders for their perspectives and experiences. This method is characterized by a sequential process where data collection precedes ethical analysis, with researchers acting as the primary interpreters of empirical findings. The approach is grounded in the assumption that while stakeholder experiences provide crucial contextual information, the specialized training of ethicists is necessary for rigorous normative analysis.

In consultative methodology, empirical data serves as a testing ground for elements of normative theory [2]. Researchers identify ethical issues in practice and understand the context of bioethical issues through engagement with stakeholders, but retain authority over the final ethical analysis and recommendations. This approach aligns with what some have termed "the handmaiden model," where social science methods serve to document facts that ethicists then use in their normative arguments [2]. The consultative approach is particularly prevalent in research aiming to develop evidence-based policy recommendations or clinical guidelines where researcher expertise drives the normative conclusions.

Dialogical Approach

The dialogical approach represents a more integrated methodology that emphasizes mutual understanding achieved through collaboration rather than shared understanding imposed by researchers [16]. Rooted in dialogical self-theory and narrative approaches, this methodology conceptualizes knowledge as co-created through dialogue between different perspectives [16] [17]. Unlike the consultative approach, dialogical methods treat participants as active collaborators in the ethical analysis rather than merely as sources of data.

The philosophical foundations of the dialogical approach draw from Bakhtinian dialogism, which views knowledge as emerging through genuine dialogue between different voices and perspectives [16] [17]. This approach produces knowledge that is pluralistic and multivocal, intentionally including underrepresented voices that might be silenced in traditional methodologies [16]. In practice, dialogical bioethics involves creating spaces where diverse stakeholders (patients, clinicians, researchers) engage in structured dialogue about ethical questions, with the research outcomes emerging from these interactions rather than being determined solely by researcher analysis.

Table: Theoretical Foundations of Consultative and Dialogical Approaches

| Dimension | Consultative Approach | Dialogical Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Epistemology | Knowledge derived from expert analysis of stakeholder data | Knowledge co-constructed through dialogue between multiple perspectives |

| Researcher Role | Expert analyst who maintains control over ethical reasoning | Facilitator and participant in collaborative meaning-making |

| Participant Role | Sources of empirical data about experiences and values | Active collaborators in ethical reflection and analysis |

| Primary Strength | Clear normative conclusions based on ethical expertise | Inclusion of diverse voices and contextual understanding |

| Integration Method | Sequential: empirical data collection followed by ethical analysis | Concurrent: ethical analysis emerges through dialogical process |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Characteristics

Research Processes and Integration Methods

The consultative and dialogical approaches differ significantly in their research processes, particularly in how they integrate empirical and normative elements. Consultative methodologies typically employ a linear sequence where empirical data collection precedes ethical analysis. For example, researchers might conduct interviews or surveys to gather stakeholder perspectives on an ethical issue, then analyze this data using philosophical frameworks independently of the participants [2]. This separation of data collection from ethical analysis allows for methodological clarity but risks imposing external theoretical frameworks on participant experiences.

Dialogical approaches employ an integrative process where empirical and normative elements interweave throughout the research. These methodologies create spaces for what is termed "therapeutic conversations" that transcend linear intervention models [17]. In practice, this might involve facilitated dialogues where patients, clinicians, and ethicists collaboratively explore ethical questions, with insights emerging through the dialogical process itself. The integration occurs in real-time through what is described as "self-reflexive dialogue" and "dialogue between the researcher and others" including interviewees, supervisors, and collaborators [16]. This process values the unique perspectives each participant brings to understanding complex phenomena.

Applications in Healthcare and Research Contexts

Both methodological approaches have distinct applications across healthcare and research contexts, with each offering particular advantages for different research questions and settings. Consultative approaches have proven valuable in contexts requiring clear normative guidance or policy development, such as establishing guidelines for ethical research protocols [12]. The structured nature of consultative methodology lends itself well to producing actionable recommendations for institutional ethics committees or clinical practice guidelines.

Dialogical approaches excel in contexts requiring deep understanding of diverse perspectives and ethical complexities, such as person-centered care in acute settings [18] or cross-cultural healthcare relationships [19]. These methods have been successfully applied in mental health contexts, where the exploration of patient experiences and values benefits from collaborative meaning-making [17] [19]. The emphasis on mutual understanding makes dialogical approaches particularly suitable for exploring contested ethical terrain where multiple legitimate perspectives exist, such as in cross-cultural research or community engagement initiatives.

Table: Methodological Applications and Outputs

| Research Context | Consultative Approach Applications | Dialogical Approach Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Ethics | Development of clinical guidelines and protocols | Understanding patient experiences of moral dilemmas |

| Research Ethics | Protocol review and compliance assessment | Stakeholder engagement in ethical governance |

| Mental Health | Analysis of ethical issues in treatment practices | Collaborative exploration of therapeutic relationships |

| Cross-Cultural Settings | Identifying cultural variations in ethical attitudes | Facilitating mutual understanding across differences |

| Policy Development | Evidence-based policy recommendations | Inclusive deliberation processes |

Experimental Protocols and Research Designs

Protocol Template for Empirical Bioethics Research

Recent methodological advances have produced formalized protocol templates suitable for various humanities and social sciences investigations in health, including empirical bioethics. These templates build upon the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) but have been adapted to overcome limitations of being restricted to qualitative approaches [12]. The refined template is equally suitable for quantitative, mixed-method, and integrated approaches, serving as a highly adaptable base for empirical bioethics research regardless of methodological orientation.

The standardized protocol includes several key components: (1) clear articulation of the ethical question and its practical significance; (2) methodological approach and justification; (3) data collection procedures; (4) integration strategy for empirical and normative elements; (5) analysis framework; and (6) dissemination plan. For consultative approaches, the protocol typically specifies separate sections for empirical data collection and ethical analysis, while dialogical approaches describe facilitated dialogue processes and collaborative analysis methods [12]. This protocol standardization enhances methodological rigor while allowing flexibility for different epistemological orientations.

Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

The consultative and dialogical approaches employ distinct data collection and analysis procedures reflecting their different epistemological commitments. Consultative methodologies often utilize structured interviews, surveys, or document analysis to gather data about stakeholder experiences and values [2]. Analysis typically involves thematic analysis of empirical data followed by application of ethical frameworks by researcher experts. This separation allows for clear methodological demarcation but risks disconnecting ethical analysis from lived experiences.

Dialogical approaches employ facilitated dialogues, group discussions, or narrative exchanges that simultaneously generate data and facilitate ethical reflection [16] [17]. Analysis focuses on understanding the evolution of perspectives through dialogue and identifying insights that emerge through collaborative exchange. Rather than applying predetermined ethical frameworks, dialogical analysis seeks to identify how ethical understanding develops through multivocal engagement. These procedures have been refined through empirical bioethics training programs that specifically teach dialogical integration methodologies [6] [18].

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Essential Research Solutions for Empirical Bioethics

Conducting rigorous empirical bioethics research requires specific methodological "reagents" and tools that facilitate data collection, analysis, and integration of empirical and normative elements. These tools differ significantly between consultative and dialogical approaches, reflecting their distinct epistemological commitments and research processes.

Table: Essential Methodological Tools for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Tool Category | Consultative Approach Tools | Dialogical Approach Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Instruments | Structured interview protocols; Survey questionnaires; Data extraction forms | Dialogue facilitation guides; Narrative elicitation techniques; Group process protocols | Gather empirical data about ethical issues (consultative) or create conditions for collaborative dialogue (dialogical) |

| Analysis Frameworks | Thematic analysis coding schemes; Ethical framework application tools; Normative analysis templates | Dialogical content analysis; Polyvocal interpretation methods; Position exchange mapping | Analyze empirical data (consultative) or interpret dialogical exchanges (dialogical) |

| Integration Methodologies | Sequential integration protocols; Empirical data mapping to ethical concepts; Normative recommendation development | Reciprocal elucidation processes; Mutual understanding facilitation; Collaborative meaning-making techniques | Connect empirical findings with ethical analysis through researcher mediation (consultative) or stakeholder collaboration (dialogical) |

| Validation Methods | Member checking; Peer debriefing; Theoretical triangulation | Dialogical validation; Stakeholder resonance assessment; Process authenticity verification | Ensure trustworthiness of findings through methodological rigor (consultative) or dialogical authenticity (dialogical) |

Comparative Performance and Outcomes

Empirical Evidence and Research Findings

The comparative performance of consultative and dialogical approaches can be evaluated through their application in various research contexts and the distinct outcomes they generate. Research indicates that consultative approaches are particularly effective for producing clear normative guidance and actionable recommendations for specific ethical dilemmas [2]. Studies using consultative methodologies have successfully identified ethical issues in clinical practice and developed context-sensitive guidelines for complex healthcare scenarios. The strength of these approaches lies in their ability to leverage ethical expertise while being informed by stakeholder experiences.

Dialogical approaches demonstrate particular strength in generating rich contextual understanding and inclusive ethical insights that incorporate diverse perspectives. Studies employing dialogical methods have revealed nuanced understandings of ethical issues in clinical relationships [19] and mental health care [17]. For example, research on online health communities revealed significant cross-cultural differences in how patients express concerns and how professionals respond, with Italian patients using more indirect and polite forms while Polish patients employed a more direct style [19]. These culturally nuanced understandings emerged through dialogical engagement with diverse participant voices.

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

Each methodological approach presents distinct strengths and limitations that make them suitable for different research questions and contexts. Consultative approaches offer methodological clarity, efficiency in analysis, and clear attribution of normative authority. These strengths make them valuable for policy development and time-sensitive ethical analysis. However, they risk imposing external frameworks on participant experiences and may miss important nuances embedded in diverse perspectives [2].

Dialogical approaches excel in including marginalized voices, generating mutual understanding, and revealing unexpected insights through collaborative exchange. These methods are particularly valuable for exploring complex ethical terrain where multiple legitimate perspectives exist. However, they can be methodologically demanding, time-intensive, and may produce less definitive normative guidance [16]. The choice between approaches ultimately depends on research questions, resources, and whether the primary goal is definitive normative guidance or deep understanding of multiple perspectives.

Table: Performance Comparison Across Methodological Criteria

| Evaluation Criteria | Consultative Approach | Dialogical Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Normative Clarity | High - produces clear ethical recommendations | Variable - may generate multiple legitimate perspectives |

| Stakeholder Inclusion | Moderate - includes voices as data sources | High - active collaboration in ethical analysis |

| Methodological Transparency | High - clear separation of empirical and normative elements | Moderate - integrated process can be complex to document |

| Cross-Cultural Sensitivity | Variable - risks imposing dominant ethical frameworks | High - designed to accommodate diverse perspectives |

| Practical Applicability | High - produces actionable recommendations | Variable - insights may require further translation |

The consultative and dialogical approaches represent distinct but complementary poles on the methodological spectrum of empirical bioethics. Rather than positioning these approaches as mutually exclusive, researchers are increasingly recognizing the value of methodological pluralism that selects approaches based on specific research questions, contexts, and goals. The ongoing evolution of empirical bioethics suggests a growing emphasis on deliberate integration of empirical and theoretical elements, with some scholars advocating for a 'theoretical turn' that strengthens engagement with philosophical theory while maintaining robust empirical foundations [15].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this methodological spectrum enables more informed choices about research design. Consultative approaches offer efficiency and normative clarity for contexts requiring definitive guidance, while dialogical approaches provide depth and inclusion for exploring complex ethical terrain. Future methodological development will likely focus on refined integration techniques and hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both poles while mitigating their limitations. As empirical bioethics continues to mature, this methodological sophistication will enhance its contribution to addressing pressing ethical challenges in healthcare innovation and practice.

Empirical bioethics emerged as a response to the perception that purely philosophical approaches were insufficient to address the complexity of real-world bioethical issues [20]. This interdisciplinary field seeks to integrate empirical data about stakeholder values, attitudes, and experiences with normative ethical theorizing [21]. Despite decades of methodological development, fundamental philosophical tensions persist regarding how to bridge the descriptive "is" of empirical research with the normative "ought" of ethical prescriptions [2]. This comparison guide examines the current landscape of empirical bioethics methodologies, their philosophical underpinnings, and their capacity to generate justified normative conclusions.

Comparative Analysis of Empirical Bioethics Approaches

A systematic review of the field identified 32 distinct methodological approaches for integrating empirical research with normative analysis [21]. These can be broadly categorized into three main types based on their structure and philosophical commitments.

Table 1: Typology of Empirical Bioethics Methodologies

| Methodological Category | Philosophical Orientation | Locus of Moral Authority | Key Characteristics | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultative Approaches (e.g., Reflective Equilibrium) | Coherentist epistemology | Researcher as independent thinker | Researcher conducts back-and-forth reflection between empirical data and ethical principles until moral coherence is achieved [20] | Process often described as vague; weight given to empirical data versus theory remains unclear [20] |

| Dialogical Approaches (e.g., Inter-ethics) | Deliberative democratic | Stakeholders in dialogue | Relies on dialogue between researchers and participants to reach shared understanding and normative conclusions [21] [20] | Application of ethical theories may depend on facilitator's subjective judgment [20] |

| Inherent Integration Approaches | Pragmatist | Practice and experience | Normative and empirical dimensions are intertwined from the project's inception rather than combined sequentially [20] | Lack of clear methodological steps may raise questions about justification of conclusions |

Hierarchical Framework for Empirical Research in Bioethics

Beyond methodological typologies, empirical research contributes to bioethics at different levels of normative significance. One framework classifies these contributions into four hierarchical categories, from descriptive to normative.

Table 2: Four-Level Hierarchy of Empirical Research in Bioethics

| Level | Primary Research Question | Example Studies | Normative Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lay of the Land | "What are current practices, opinions, or beliefs?" | Studies of ethics committee composition; surveys of end-of-life care attitudes [11] | Descriptive foundation; informs decision-making without direct normative claims |

| 2. Ideal Versus Reality | "To what extent does practice align with ethical ideals?" | Research on disparities in healthcare delivery; studies of informed consent comprehension [11] | Identifies ethical shortcomings in current practice; demonstrates need for improvement |

| 3. Improving Care | "How can we bring practice closer to ethical ideals?" | Interventions to reduce healthcare disparities; programs to improve informed consent processes [11] | Develops and tests practical strategies to implement ethical norms |

| 4. Changing Ethical Norms | "Should our ethical frameworks evolve based on empirical findings?" | Syntheses of multiple empirical studies to challenge or refine ethical principles [11] | Uses cumulative empirical evidence to propose modifications to ethical theory |

Researcher Perspectives on Methodological Implementation

Recent qualitative research exploring bioethics scholars' experiences reveals both consensus and contention regarding appropriate objectives for empirical bioethics research.

Researcher Consensus and Debate on Objectives

Qualitative exploration with researchers conducting empirical bioethics reveals varying levels of acceptance for different research objectives [2]:

Universally Accepted Objectives:

- Understanding the context of a bioethical issue

- Identifying ethical issues in practice

Contentious Objectives:

- Striving to draw normative recommendations

- Developing and justifying moral principles

The is-ought gap was not considered an insurmountable obstacle by most researchers but rather a warning sign prompting critical reflection on the normative implications of empirical results [2]. The potential of empirical research to be useful for bioethics was mostly based on the reasoning pattern that empirical data can provide a testing ground for elements of normative theory [2].

Methodological Protocols in Empirical Bioethics

Reflective Equilibrium Protocol

The most familiar consultative method, reflective equilibrium, follows this systematic protocol [20]:

- Initial Position Mapping: Identify preliminary moral intuitions about the case

- Theory Examination: Consider relevant ethical principles and theories

- Empirical Data Integration: Incorporate empirical findings about stakeholder experiences, attitudes, or practices

- Coherence Seeking: Engage in iterative reflection to align moral intuitions, principles, and empirical observations

- Equilibrium Achievement: Reach a state of reflective coherence where all elements support a normative position

Dialogical Integration Protocol

Dialogical approaches employ a different methodological structure [21] [20]:

- Stakeholder Identification: Recruit diverse participants with relevant perspectives and experiences

- Structured Deliberation: Facilitate dialogue using established deliberative techniques

- Ethical Framework Introduction: Introduce ethical concepts to enrich discussion without predetermined conclusions

- Shared Understanding Development: Collaboratively develop moral perspectives through exchange

- Normative Conclusion Formulation: Arrive at justified normative positions through collective reasoning

Essential Research Reagents for Empirical Bioethics

Unlike laboratory sciences, empirical bioethics relies on methodological and analytical tools rather than physical reagents.

Table 3: Essential Methodological Reagents for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Examples of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Interview Protocols | Elicit rich, nuanced data about moral experiences and reasoning | Exploring how patients conceptualize autonomy in clinical decision-making [2] |

| Deliberative Dialogue Frameworks | Structure stakeholder discussions to generate morally justified outcomes | Facilitating conversations between clinicians, patients, and policymakers on resource allocation [20] |

| Normative-Analytical Templates | Systematically trace relationships between empirical findings and ethical principles | Mapping how facts about cultural variations in truth-telling inform norms of disclosure [11] |

| Reflective Equilibrium Worksheets | Document the iterative process of achieving coherence between data and theory | Tracking how initial intuitions about disability evolve after engagement with empirical evidence [20] |

| Integration Methodologies | Explicit frameworks for combining empirical and normative analysis (e.g., symbiotic ethics, grounded moral analysis) [20] | Providing structured approaches to ensure empirical data properly informs normative conclusions |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite methodological proliferation, researchers report ongoing challenges with integration, describing their processes with "an air of uncertainty and overall vagueness" [20]. This indeterminacy represents a double-edged sword—allowing flexibility while potentially obscuring insufficient methodological understanding.

The most significant tension remains between researchers who view empirical data as primarily illuminating context and those who advocate for its capacity to directly inform normative recommendations [2]. This divide reflects deeper philosophical disagreements about moral justification that play out within bioethical methodology [21].

Future methodological development must address the need for both conceptual clarity and practical applicability, enabling researchers to navigate the fundamental tension between descriptive and normative claims while producing work that meaningfully contributes to resolving pressing bioethical dilemmas in healthcare and research.

Empirical bioethics is an interdisciplinary field that integrates empirical findings from the social sciences with normative, philosophical analysis to address practical issues in healthcare, medicine, and research [20] [22]. This integration aims to address the complexity of human practices more effectively than purely philosophical approaches alone [20]. Despite general agreement that empirical research is relevant to bioethical argument, significant methodological diversity exists regarding how to classify research aims and integrate empirical data with normative analysis [23] [20] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the predominant typologies used to classify research aims in empirical bioethics, from merely describing attitudes toward the more ambitious goal of changing ethical norms, offering researchers a structured overview of the methodological landscape.

A central challenge in this field is the is-ought gap, a philosophical problem highlighting the difficulty of deriving ethical prescriptions (what "ought" to be) solely from empirical facts (what "is") [24] [2] [25]. Despite this challenge, empirical research is widely recognized as crucial for illuminating the context of ethical issues, testing the practical application of norms, and informing the development of ethical recommendations [2] [11] [25]. The typologies discussed below represent different ways scholars have organized these varied aims into a coherent framework.

Comparative Framework of Research Aims

Kon's Hierarchical Framework of Empirical Research

One influential classification, proposed by Kon, organizes empirical research in bioethics into a four-level hierarchy that increases in normative ambition [11]. This framework is instrumental for understanding how different research questions contribute to the field, with each level building upon the knowledge generated by the previous one.

The table below summarizes this hierarchical model:

Table 1: Kon's Hierarchical Framework of Empirical Research in Bioethics

| Category | Primary Research Question | Example | Normative Ambition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lay of the Land | "What are current practices, opinions, or beliefs?" | Studies surveying the attitudes of physicians, patients, or ethics committee members on a specific issue [11]. | Low |

| Ideal Versus Reality | "To what extent does clinical practice match ethical ideals?" | Research documenting disparities in healthcare provision across different racial or ethnic groups [11]. | Low to Medium |

| Improving Care | "How can we bring practice closer to ethical ideals?" | Interventions or programs designed to improve the process of informed consent for clinical research [11]. | Medium |

| Changing Ethical Norms | "Should our ethical ideals be revised based on empirical data?" | Using aggregated empirical findings to argue for a change in specific ethical norms or guidelines [11]. | High |

Categorical Objectives of Empirical Research

Complementing Kon's hierarchical model, other scholars have proposed a list of distinct objectives for Empirical Research in Bioethics (ERiB). A qualitative study exploring the acceptability of these objectives among bioethics researchers found varying levels of support, revealing a clear preference for more modest aims [2] [25].

The continuum of objectives, from least to most ambitious, along with researcher agreement, is detailed below:

Table 2: Researcher Agreement on Objectives of Empirical Bioethics Research

| Research Objective | Description | Level of Ambition | Researcher Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding Context | Exploring the context and reality of a bioethical issue [2]. | Low | Unanimous agreement [2] [25]. |

| Identifying Ethical Issues | Pinpointing ethical problems as they manifest in practice [2]. | Low | Unanimous agreement [2] [25]. |

| Informing Applied Ethics | Providing data to enrich the application of ethical principles in specific settings [2]. | Medium | Supported, with varying degrees of agreement [2] [25]. |

| Testing Ethical Theory | Examining the validity of concepts, principles, or theories in real-world settings [2]. | Medium | Supported, with varying degrees of agreement [2] [25]. |

| Evaluating Interventions | Assessing how an ethical recommendation or intervention plays out in practice [2] [25]. | Medium | Supported, with varying degrees of agreement [2] [25]. |

| Drawing Normative Recommendations | Using empirical data to suggest changes to specific ethical norms or practices [2]. | High | The most contested objective [2] [25]. |

| Developing/Justifying Moral Principles | Using empirical research to contribute to the development or justification of general moral principles [2]. | High | The most contested objective [2] [25]. |

Methodological Approaches for Integration

A systematic review identified 32 distinct methodologies for integrating empirical research with normative analysis in bioethics, which can be broadly categorized by their underlying philosophical commitments and analytical processes [23]. Understanding these methodologies is crucial for selecting the right approach to match a study's aims.

Dialogical and Consultative Methodologies

The majority of integrative methodologies can be classified as either dialogical or consultative, which represent two different orientations toward how normative conclusions are reached [23].

Table 3: Core Methodological Approaches in Empirical Bioethics

| Methodology | Description | Key Feature | Example Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consultative | The researcher analyzes empirical data independently as an external thinker to develop a normative conclusion [23] [20]. | Researcher-driven analysis | Reflective Equilibrium, Reflexive Balancing [23] [20]. |

| Dialogical | Relies on structured dialogue among stakeholders (e.g., researchers, participants) to reach a shared understanding and normative conclusion [23] [20]. | Collaborative, process-driven analysis | Inter-ethics, Dialogical Empirical Ethics [23] [20]. |

The Reflective Equilibrium Method

One prominent consultative method is Reflective Equilibrium, a process tailored for empirical bioethics projects [20]. It is a two-way dialogue between ethical principles, values, and empirical data (often from the researcher's own study) [20]. The researcher, or "the thinker," moves back and forth between the normative underpinnings and the empirical facts until a state of moral coherence, or "equilibrium," is produced [20]. The workflow of this iterative process is visualized below.

Key Research Reagents for Empirical Bioethics

Executing a rigorous empirical bioethics study requires specific methodological "reagents" or tools. The table below details essential components for designing and implementing such research, explaining the function of each.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Empirical Bioethics Studies

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interviews | To gather rich, qualitative data on participants' experiences, moral reasoning, and views on a bioethical issue. | Exploring how clinicians experience and navigate ethical dilemmas in end-of-life care [20]. |

| Systematic Literature Reviews | To synthesize existing empirical data from a wide range of sources, forming a comprehensive evidence base for normative analysis. | Reviewing clinical evidence on tube feeding outcomes in patients with advanced dementia to inform ethical debates [5]. |

| Dialogical Workshops | To facilitate structured, collaborative discourse among stakeholders, enabling the co-creation of normative insights. | Bringing together patients, researchers, and ethicists to develop guidelines for a contentious clinical practice [23] [20]. |

| Qualitative Coding & Thematic Analysis | To systematically identify, analyze, and report patterns (themes) within qualitative data, linking empirical findings to ethical concepts. | Analyzing interview transcripts to understand key factors that influence volunteers' decision to participate in research [20] [2]. |

| The Wide Reflective Equilibrium Framework | To provide a structured methodological process for integrating empirical findings with ethical principles and considered judgments. | Justifying a normative recommendation by showing its coherence with empirical data on patient preferences and principles of autonomy [20]. |

Discussion: Navigating Methodological Challenges

Researcher Perspectives on Ambitious Aims

Despite the availability of numerous methodologies, the process of integration in practice is often described as vague and indeterminate [20]. Interviews with bioethics scholars reveal an "air of uncertainty" surrounding how to combine the normative and the empirical effectively [20]. This indeterminacy is a double-edged sword: it allows for methodological flexibility but also risks obscuring a lack of understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of empirical bioethics research [20].

This practical uncertainty is reflected in the divergent views researchers hold regarding the objectives of their work. As shown in Table 2, while understanding context and identifying ethical issues receive unanimous support, the more ambitious aims—particularly drawing normative recommendations and developing moral principles—are the most contested [2] [25]. This suggests that the acceptability of an objective is inversely related to its normative ambition. Researchers are generally comfortable using empirical data to inform the normative realm, primarily as a "testing ground for elements of normative theory," but are more cautious about using it to determine normative conclusions [2] [25].

The "Hidden" Nature of Ethically Relevant Data

A significant practical challenge in empirical bioethics is that much ethically relevant empirical research is "hidden" from view [5]. Key studies are often published in non-ethics journals by professionals who do not identify as ethicists, and without ethics-related keywords [5]. For example, a foundational study on tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia was published in JAMA by geriatric physicians, and a study on suicide risk in antidepressant trials was published in a psychiatry journal; both have been extensively cited in ethical debates [5]. This highlights that the value of empirical research for bioethics lies in its scientific rigor and relevance, not in the affiliation of the investigators or the journal it is published in [5] [11]. Researchers must therefore be skilled at searching beyond traditional bioethics sources and collaborating with professionals from other fields to access this critical data [5].

The typologies of research in empirical bioethics, from describing attitudes to changing norms, provide a valuable map for navigating this complex field. Kon's hierarchical framework and the continuum of research objectives offer complementary lenses for classifying research aims and understanding their varying levels of normative ambition. While a diverse toolkit of methodologies exists—from reflective equilibrium to dialogical approaches—successful research requires careful selection of a method that aligns with the study's goals and a clear-eyed view of the challenges, including the is-ought gap and the practical difficulties of integration. For drug development professionals and other researchers, this comparative guide underscores that the most effective empirical bioethics research is often that which thoughtfully matches its methodological approach to the specific research question, whether its aim is to describe a landscape or to help reshape its normative boundaries.

A Practical Guide to Prominent Empirical Bioethics Methods and Their Application

Comparative Analysis of Empirical Bioethics Methodologies

Within the expanding field of empirical bioethics, a critical challenge persists: how to effectively integrate diverse stakeholder perspectives to navigate complex moral questions in healthcare and biomedical research. This guide provides a comparative analysis of prominent empirical bioethics methodologies, with a specific focus on evaluating dialogical approaches that facilitate moral learning through structured stakeholder collaboration. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting an appropriate methodology is paramount for generating ethically robust and practically applicable results. This article objectively compares the performance, data requirements, and outputs of key methodological approaches, supporting the broader thesis that the conscious comparative study of these methods enriches the entire discipline. We present experimental data and detailed protocols to illustrate how these approaches are operationalized in contemporary bioethical research.

Methodological Comparison

Empirical bioethics methodologies vary significantly in their procedures, analytical frameworks, and ultimate objectives. The table below provides a structured comparison of four prominent approaches, highlighting their distinct applications in facilitating stakeholder dialogue.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Empirical Bioethics Methodologies

| Methodology | Primary Procedure | Key Analytical Approach | Typical Output | Illustrative Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Cross-Cultural Analysis [26] | Qualitative data collection (e.g., surveys, interviews) across different cultural or national settings. | Thematic analysis to identify similarities and differences in ethical attitudes and practices. | Evidence base for understanding cultural nuances; informs training and policy. | Comparison of Chinese and Japanese doctors' attitudes toward patient death and error disclosure [26]. |

| Stakeholder Roundtables [27] | Structured, facilitated discussions among diverse stakeholders (e.g., industry, regulators, patients). | Consensus-building and normative argumentation to define metrics and ethical frameworks. | Ethical frameworks, reporting standards, and consensus statements. | Yale/EY roundtable developing metrics for patient centricity and clinical trial transparency in pharma [27]. |

| Media Debate Analysis [28] | Systematic collection and examination of media content (news, social media). | Qualitative content analysis to identify prevailing moral arguments and societal values. | Map of public moral landscape; identification of overlooked or emergent ethical problems. | Analysis of public discourse on AI in healthcare to identify biases and societal concerns [29] [28]. |

| Empirical Qualitative Engagement [26] | In-depth interviews and focus groups with key stakeholders within a specific context. | Grounded theory or descriptive qualitative analysis to unpack granular factors and lived experiences. | Deep, context-specific understanding of a phenomenon and its underlying ethical dimensions. | Study of factors leading to the proliferation and fragmentation of medical clinics in Pakistan [26]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility, this section details the experimental protocols for two key dialogical approaches: the Stakeholder Roundtable and Media Debate Analysis.

Protocol 1: Stakeholder Roundtable for Metric Development

This protocol is modeled on the "Ethics, Trust + Patient Centricity in Pharma" roundtable [27], designed to define success metrics through collaborative dialogue.

- Participant Recruitment and Preparation: Convene a multidisciplinary group of 40-60 stakeholders. This includes pharmaceutical executives, regulatory officials (e.g., from FDA, EMA), patient advocacy leaders (e.g., from Global Genes, NORD), academic bioethicists, and investors [30] [27].

- Structured Agenda Facilitation: Execute a full-day agenda with timed sessions:

- Opening Keynotes (1.5 hours): Set the stage with talks from former FDA commissioners and lead bioethicists on ethical commitments and current performance trends [27].

- Focused Panel Discussions (3 hours): Conduct panels on specific themes, such as clinical trial transparency and demographic representation. Each panel includes brief opening remarks followed by moderated discussion [27].

- Small Group Brainstorming (1 hour): Divide participants into small, facilitated groups of approximately 10 people to brainstorm specific projects, themes, and metrics [27].

- Plenary Synthesis (1.5 hours): Reconvene for a full roundtable discussion to share small-group outputs and define collective next steps [27].

- Data Collection and Analysis: Data consists of audio recordings, transcribed proceedings, and written outputs from brainstorming sessions. Analysis involves thematic synthesis to identify consensus points, contested areas, and concrete, measurable metrics for ethical performance.

- Output Implementation: The synthesized findings are used to shape accountability tools, such as refining the "Good Pharma Scorecard" to advance patient-centric and trustworthy practices in medicines development [27].

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, collaborative workflow of this roundtable protocol.

Protocol 2: Systematic Media Debate Analysis

This protocol, derived from established research in the field, outlines the process for analyzing media debates to understand the public dimension of bioethical issues [28].

- Research Question and Source Definition: Formulate a precise question (e.g., "How are ethical concerns about AI-driven insurance denials framed in public media?"). Define the media corpus, including specific news outlets (legacy media) and public social media platforms, setting a date range and search terms [29] [28].

- Data Collection and Corpus Compilation: Systematically gather all relevant media items using database searches (e.g., LexisNexis) and platform APIs. Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria to create a final corpus for analysis.

- Qualitative Content Analysis: Code the media content in multiple passes. The first pass identifies broad themes (e.g., "bias," "accountability," "efficiency"). Subsequent passes perform a deeper analysis of ethical arguments, rhetorical frames, and the presence or absence of specific stakeholder voices [29] [28].

- Interpretation and Ethical Evaluation: Synthesize the coded data to map the dominant "moral landscape" of the issue. The analysis can identify morally problematic media framings (e.g., age-based stereotypes) and evaluate the quality of public ethical deliberation [28].

The workflow for this analytical method is a sequential, research-driven process, as shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of dialogical bioethics research requires both conceptual and practical tools. The table below details key "research reagents" essential for conducting the experiments and analyses described in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Item | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Map | A visual tool identifying all relevant individuals, groups, and organizations with a stake in the bioethical issue. | Ensuring representative participation in a roundtable on clinical trial demographics, including patients, regulators, and industry scientists [27]. |

| Structured Interview/Focus Group Guides | A pre-defined set of open-ended questions used to ensure consistency and comprehensiveness in qualitative data collection. | Exploring the attitudes of Chinese and Japanese physicians using a uniform hypothetical scenario about patient death [26]. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo, Atlas.ti) | Software designed to facilitate the coding, categorization, and thematic analysis of unstructured text data. | Managing and analyzing large corpora of media reports or interview transcripts to identify emergent ethical themes [28]. |

| Consensus-Building Frameworks (e.g., Delphi method) | Structured communication techniques used to distill the opinions of experts into a cohesive group judgment. | Facilitating small-group brainstorming sessions in a roundtable to define core metrics for patient centricity [27]. |

| Ethical Framework Template | A skeletal structure outlining key ethical principles (e.g., autonomy, justice, beneficence) to guide normative analysis. | Developing a religiously sensitive ethical framework for conducting clinical post-mortem examinations in Saudi Arabia [26]. |

Discussion of Performance and Outcomes

Each methodological approach offers distinct advantages and generates different forms of evidence, making them suited to specific research questions within the drug development and biomedical research landscape.

Stakeholder Roundtables excel in generating normative frameworks and actionable metrics. Their performance is measured by their ability to forge consensus among powerful, often competing, stakeholders. For example, the roundtable involving the FDA, EMA, and pharmaceutical companies directly addresses revising global industry standards for clinical trial transparency [27]. The primary data supporting their efficacy is the adoption of their outputs into policy tools like the Good Pharma Scorecard.

Media Debate Analyses provide critical insights into the societal context in which bioethical decisions are made. Their value lies in identifying public concerns, such as algorithmic bias in AI-driven insurance denials or the erosion of trust in health technologies, which may be overlooked in expert-driven dialogues [29] [28]. The quantitative data from one analysis revealed that only 16% of bioethics journals had a clear AI policy, highlighting a significant gap between a pressing public issue and institutional guidance [7]. This method's outcome is a map of the public moral landscape, which is essential for anticipating implementation challenges and ensuring the social robustness of ethical guidelines.

Comparative Cross-Cultural and Qualitative Studies deliver granular, context-specific understanding that prevents the uncritical transplantation of ethical norms. The experimental data from the China-Japan study revealed that fear of physical reprisals significantly influenced Chinese doctors' communication practices following a medical error—a finding with immediate implications for designing culturally competent ethics training [26]. The performance of this method is validated by its ability to uncover such critical, ground-level nuances that inform effective and localized ethical practice.

In conclusion, the dialogical approaches compared herein are not mutually exclusive but are complementary. A comprehensive empirical bioethics strategy may leverage media analysis to identify a public problem, use qualitative studies to understand its on-the-ground impact, and convene a stakeholder roundtable to develop a consensus-based solution. For professionals in drug development, this multifaceted understanding is crucial for navigating the complex interplay of science, ethics, and society, ultimately fostering moral learning that is both deeply informed and broadly legitimate.