Integrating Theological Bioethics in Clinical Practice: A Framework for Humanized Patient Care and Ethical Drug Development

This article addresses the growing need to validate theological and religious perspectives within secular bioethics, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals navigating complex ethical landscapes.

Integrating Theological Bioethics in Clinical Practice: A Framework for Humanized Patient Care and Ethical Drug Development

Abstract

This article addresses the growing need to validate theological and religious perspectives within secular bioethics, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals navigating complex ethical landscapes. It explores the historical secularization of bioethics and the contemporary gap created by technologically-driven frameworks like transhumanism and AI, which often sideline the spiritual dimensions of personhood. The content provides a methodological framework for integrating theological reasoning into clinical and research ethics, troubleshoots common implementation challenges such as interdisciplinary communication and institutional resistance, and validates the approach through comparative analysis with secular principlism and evidence of improved patient outcomes. By synthesizing foundational concepts, practical applications, and empirical validation, this article argues for the essential role of theological bioethics in fostering holistic, humanized healthcare and responsible scientific innovation.

The Secular Shift and the Case for Theological Re-engagement in Bioethics

The field of bioethics represents a critical intersection of medicine, morality, and philosophy, governing how society approaches complex biological and medical dilemmas. This domain has undergone a significant transformation from its origins in religious tradition to its current predominantly secular character. Understanding this evolution is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who operate within ethical frameworks that often carry implicit philosophical assumptions. The historical transition from theological to secular foundations represents more than merely a shift in vocabulary; it constitutes a fundamental reorientation of the underlying principles, justification mechanisms, and authority structures that inform bioethical decision-making. This guide objectively compares these competing foundations, examining their respective frameworks, applications, and influences on contemporary clinical practice and research.

The secularization of bioethics accelerated particularly during the mid-to-late 20th century, as technological advancements in medicine presented novel ethical questions that seemed to challenge traditional religious frameworks [1]. This process was notably catalyzed by debates surrounding contraception in the 1960s, which prompted an "exodus of scholars" from theological ethics to the burgeoning field of secular bioethics [1]. Yet, as secular approaches have gained dominance, questions about their philosophical completeness and practical adequacy have persisted, leading to renewed examination of theological perspectives within pluralistic ethical discourse [2] [1].

Historical Development: From Religious Roots to Secular Frameworks

Theological Foundations of Medical Ethics

The earliest foundations of Western medical ethics were deeply embedded in religious traditions and frameworks. The Hippocratic School in ancient Greece (c. 430 BCE) produced one of the first formal medical ethical codes, yet even this "secular" development maintained connections to healing deities and cultic practices [3]. Within the Christian tradition, medical ethics initially developed as an "expression of faithfulness," with early Christian physicians like Luke (evangelist and physician) and fourth-century twins Cosmas and Damian demonstrating how scientific medicine could be practiced consistently with religious commitment [3].

The integration of faith and medicine continued through the medieval period, with religious institutions often serving as the primary custodians of medical knowledge and ethical standards. Theological bioethics fundamentally views life as a "precious gift from God" that humans are entrusted to preserve and develop as responsible stewards rather than absolute masters [2]. This perspective establishes a framework where human dignity derives from divine creation in God's image, positioning medical practice within a context of service and responsibility rather than mere technical proficiency [2].

The Secular Turn in Bioethics

The Enlightenment Project marked a pivotal turning point in ethical reasoning, with thinkers seeking foundations for morality that could be discovered through human reason alone, independent of religious authority [4]. This philosophical shift eventually influenced medical ethics, particularly as rapid biomedical advancements in the mid-20th century presented novel ethical dilemmas that seemed to demand universally accessible frameworks [1].

The emergence of bioethics as a distinct field is frequently attributed to Van Rensselaer Potter II, who conceptualized it as a "science for survival" [2]. This secular orientation gained institutional traction through initiatives like the Bioethics Interest Group at the National Institutes of Health, which provides a discussion forum for ethical issues in biomedical research without explicit religious foundation [5]. The secularization process was further advanced through governmental initiatives such as the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, which developed pedagogical materials to support ethics education in diverse professional settings [6].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Bioethical Thought

| Time Period | Dominant Framework | Key Developments | Representative Figures/Texts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Antiquity | Religious/Mystical | Healing tied to priestly activities and ritual practices | Shamanic traditions; Temple healing |

| Classical Era (c. 430 BCE) | Philosophical-Religious Blend | Natural causation emphasized alongside divine acknowledgment | Hippocratic School & Oath; Galenic medicine |

| Medieval Era | Theological Dominance | Medical ethics as expression of religious faithfulness | Cosmas and Damian; Integration of Galenic medicine with Christian theology |

| Enlightenment | Emerging Secularism | Search for reason-based morality independent of religion | Philosophical challenges to religious authority |

| Mid-20th Century | Transition Period | Theological contributions to nascent bioethics field | Paul Ramsey; Early theological bioethicists |

| Late 20th Century | Secular Dominance | Principlism emerges as dominant framework | Beauchamp & Childress; Institutionalization of secular bioethics |

Comparative Analysis: Foundational Frameworks and Principles

Theological Bioethical Frameworks

Theological approaches to bioethics maintain distinct foundational principles that shape their ethical reasoning. Christian bioethics, both Catholic and Orthodox, emphasizes the concepts of love (agape), justice, and the inherent dignity of human life as created in God's image [2]. These traditions maintain that humans are not absolute masters of life but rather "responsible managers" entrusted with stewardship of God's creation [2].

The Catholic bioethical tradition has developed a sophisticated framework emphasizing the hermeneutic key of life as directed by both human and divine purposes [2]. Important documents like Pope John Paul II's encyclical Evangelium Vitae address pressing questions in medical ethics, emphasizing freedom as the foundation of human dignity [2]. Similarly, Orthodox bioethics bases its ethical judgments on Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition, with particular emphasis on the concept of human beings created in God's "image" and with the potential to achieve "likeness" to God through the process of theosis or divinization [2].

A central differentiator of theological bioethics is its teleological perspective – the understanding that human life has a specific purpose and end goal that informs moral reasoning. This stands in sharp contrast to secular approaches that often struggle to establish a coherent foundation for human dignity without reference to transcendent purpose [4].

Secular Bioethical Frameworks

Secular bioethics emerged as a deliberate attempt to develop ethical frameworks accessible to people across diverse religious and philosophical commitments. The dominant approach became principlism, as articulated by Beauchamp and Childress, which organizes ethical analysis around four key principles: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice [1]. This framework was intended to provide a "common moral language" for resolving ethical dilemmas in pluralistic settings.

However, secular bioethics faces significant philosophical challenges in establishing foundations for its moral claims. As Alasdair MacIntyre and others have argued, without a coherent account of human purpose (telos), secular approaches struggle to provide compelling justification for why certain principles should be universally binding [4]. The Enlightenment "failure" to establish a consensus on morality based solely on reason has led to increasing fragmentation in secular ethical theories, with some approaches leaning toward moral relativism or grounding ethics primarily in subjective sentiment [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Foundational Frameworks

| Aspect | Theological Bioethics | Secular Bioethics |

|---|---|---|

| Moral Foundation | Divine revelation, natural law, and religious tradition | Human reason, principles, and consensus |

| View of Human Life | Sacred, possessing inherent dignity as created in God's image | Value determined by human attributes, capacities, or social agreement |

| Primary Motivation | Love of God and neighbor; obedience to divine command | Human flourishing; rights protection; harm prevention |

| Concept of Justice | Based on God's character; includes equitable care for all | Social contract; fair distribution of resources |

| Approach to Dilemmas | Appeal to religious authorities, texts, and traditions | Application of principles; balancing of competing values |

| Teleology | Life has divine purpose and eternal significance | Purpose is individually determined or socially constructed |

Methodological Approaches and Applications

Research Ethics and Clinical Applications

The methodological differences between theological and secular bioethics manifest distinctly in research ethics and clinical applications. Theological approaches often incorporate distinctive methodologies such as the "mind of the Church" in Orthodox tradition or the application of natural law reasoning in Catholic bioethics [2]. These approaches maintain that certain moral truths are discoverable through reason but are fully illuminated by religious revelation.

Secular methodologies dominate contemporary research ethics, particularly through frameworks like principlism, which offers a systematic approach to ethical analysis that can be applied across diverse cultural and religious contexts [1]. This approach has been institutionalized through mechanisms like Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), which primarily operate within secular ethical paradigms [5].

The clinical application of these differing methodologies reveals substantive practical differences. Theological bioethics tends to emphasize the physician-patient relationship as one of "Agape structure of love" where medicine is understood as a mission rather than merely a profession, and patients are regarded as brothers and sisters rather than purely autonomous agents [2]. Secular bioethics, by contrast, typically emphasizes patient autonomy as a primary value, with the physician's role focused on providing information and respecting patient choices within legal and professional boundaries.

Conceptual Mapping of Bioethical Reasoning

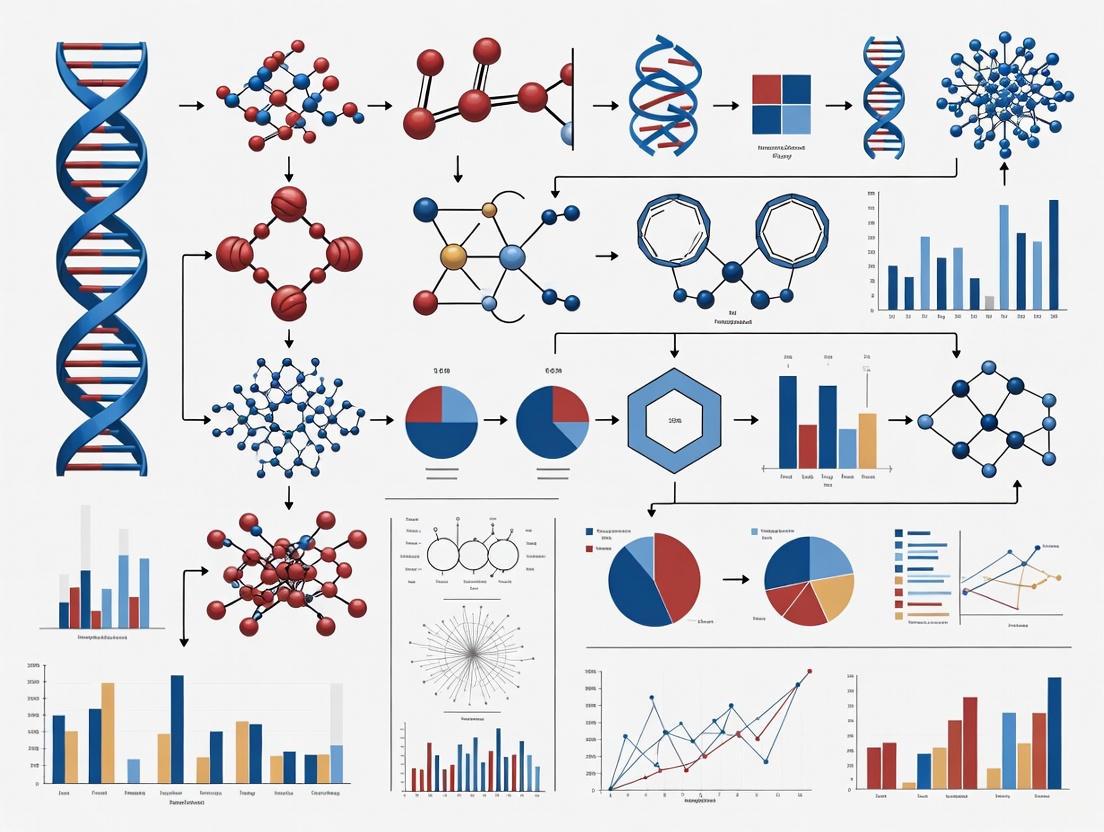

The following diagram illustrates the distinct logical pathways characteristic of theological versus secular approaches to bioethical reasoning:

Experimental Protocols and Research Methodologies

Protocol for Comparative Ethical Analysis

Objective: To systematically compare theological and secular approaches to a specific bioethical dilemma (e.g., genetic engineering, end-of-life decisions, resource allocation) and evaluate their respective reasoning processes, conclusions, and practical implications.

Materials Needed:

- Case study with complex ethical dimensions

- Reference materials from theological traditions

- Reference materials from secular ethical frameworks

- Analysis template for comparing reasoning pathways

Procedure:

- Case Presentation: Select a clinically relevant bioethical case with significant moral dimensions.

- Independent Analysis: Have theological and secular ethicists analyze the case separately using their respective frameworks.

- Reasoning Documentation: Document the step-by-step reasoning process for each approach, including:

- Identification of relevant principles/values

- Consideration of conflicting obligations

- Resolution methodology

- Final recommendation

- Comparative Evaluation: Analyze similarities and differences in:

- Foundational assumptions

- Weighting of competing values

- Practical recommendations

- Perceived strengths/limitations

Validation Metrics:

- Internal consistency of reasoning

- Clarity of foundational premises

- Practical applicability in clinical settings

- Responsiveness to stakeholder concerns

Research Reagent Solutions for Bioethical Inquiry

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Bioethical Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Principlism Framework | Provides four-principle structure for ethical analysis | Secular clinical ethics consultation; research ethics review |

| Natural Law Methodology | Reasons from human nature and purpose to moral norms | Catholic bioethical analysis; theological anthropology applications |

| Narrative Ethics Approach | Focuses on patient and practitioner stories | Complement to principle-based approaches in both traditions |

| Virtue Ethics Framework | Emphasizes character of moral agent | Theological and secular applications; professional formation |

| Casualty Analysis Protocol | Systematically examines consequences of actions | Utilitarian assessments; public policy development |

| Theological Anthropology Resources | Provides understanding of human nature and purpose | Distinctively theological bioethical reasoning |

Current Landscape and Emerging Trends

The Contemporary Resurgence of Theological Voices

Despite the continued dominance of secular frameworks in academic and clinical bioethics, there are signs of renewed engagement with theological perspectives. This resurgence stems partly from recognition of the "impoverished" nature of bioethical discourse that completely excludes religious voices and traditions [1]. The Christian BioWiki, for instance, represents a significant effort to document Christian denominational positions on bioethical issues, providing researchers with comprehensive resources for understanding theological perspectives [7].

There is growing acknowledgment that theological traditions offer robust conceptual resources for addressing novel ethical challenges posed by emerging technologies. The extensive reflection on human nature, purpose, and morality within religious traditions provides valuable frameworks for considering the ethical implications of genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and human enhancement technologies [2] [7].

Integrative Approaches and Future Directions

The current bioethical landscape shows increasing interest in integrative approaches that incorporate insights from both theological and secular perspectives without collapsing their distinctive foundations. Scholars like Jeffrey Bishop and Tristram Engelhardt have modeled approaches that take seriously both the insights of secular philosophy and the wisdom of religious traditions, particularly Orthodox Christianity [2] [1].

The clinical context often demands practical ethical resolutions that can be accepted by stakeholders from diverse philosophical and religious backgrounds. This practical necessity has led to the development of procedural approaches that focus on fair decision-making processes while allowing for substantive disagreement on foundational questions. Nevertheless, researchers and clinicians increasingly recognize that truly comprehensive bioethical analysis requires engagement with the deep philosophical and theological assumptions that underpin different approaches to medicine, health, and human flourishing.

The historical transition from theological foundations to secular dominance in bioethics represents more than an academic curiosity; it has tangible implications for how researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals approach ethical dilemmas in their work. Understanding the comparative strengths and limitations of each framework enables more sophisticated ethical analysis and promotes greater self-awareness about the presuppositions underlying different approaches to bioethical challenges.

The secularization thesis in bioethics, while accurately describing the field's institutional development, may have underestimated the enduring relevance of theological perspectives. Contemporary bioethics appears to be moving toward a more pluralistic model that makes space for both secular and religious voices, recognizing that each offers valuable insights for navigating the complex ethical terrain of modern medicine and biotechnology. For professionals engaged in clinical research and drug development, this historical perspective provides essential context for understanding current ethical frameworks and anticipating future developments in bioethical thought.

The rapid advancement of technological frameworks, particularly transhumanism and artificial intelligence (AI), presents a paradigm shift in how humanity conceptualizes its future. These disciplines, grounded in materialist and computational philosophies, increasingly influence clinical practice and biomedical research. However, a significant gap has emerged: the systematic exclusion of spiritual and theological dimensions from their foundational principles and applications. This exclusion is particularly problematic in bioethics, where questions of human dignity, purpose, and meaning intersect with medical practice [8] [9].

Transhumanism, as articulated by thinkers like Julian Huxley, Max More, and Nick Bostrom, advocates for using technology to transcend human biological limitations, envisioning a future of enhanced capabilities, extended lifespans, and even immortality [8] [10]. This vision is underpinned by technological determinism, the belief that technological progress is the primary, inevitable driver of human evolution [8]. Similarly, dominant AI narratives, influenced by figures like Ray Kurzweil and Yuval Harari, often reduce human beings to complex algorithms and data processing systems, a worldview sometimes termed Dataism [9]. This paper argues that these frameworks operate with a reductive anthropology that neglects essential aspects of human personhood, creating an urgent need for theological bioethics to engage with and validate its principles within clinical research practice.

Analytical Framework: Core Principles and Their Spiritual Contradictions

Table 1: Core Principles of Technological Frameworks vs. Theological Bioethics

| Framework | Core Principle | Anthropological View | Stance on Mortality & Finitude | Primary Ethical Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transhumanism | Human limitations are engineering problems to be solved [8] [10]. | A substrate for enhancement; conditional dignity based on capacities [8] [11]. | A flaw to be eliminated [8] [9]. | Progress, efficiency, and the transcendence of biological constraints. |

| AI Dataism | Human thought and identity are algorithms and data processing [9]. | An information processor; consciousness is an emergent property or illusion [9]. | Irrelevant if information can be preserved (digital immortality) [9]. | Optimization, pattern recognition, and data-driven decision-making. |

| Theological Bioethics | Human life is a gift with inherent dignity [8] [2]. | An integrated unity of body, mind, and spirit, created in the imago Dei [8] [2]. | A natural part of the human condition with potential meaning [8]. | The protection of human dignity, community, and spiritual flourishing. |

The gap between these technological frameworks and spiritual traditions is not merely a matter of different priorities but stems from fundamentally incompatible starting points. Transhumanism and Dataism are rooted in a materialist metaphysics that either dismisses non-material realities like consciousness and spirit or reduces them to epiphenomena of physical processes [9]. Theologian Nathan Mladin describes this as an "ambient ideology," a worldview so pervasive it escapes critical examination [11]. In contrast, theological bioethics—whether Christian, Islamic, or Jewish—begins with the premise that human beings are spiritual entities with a nature and purpose that transcend material composition [2] [9] [7]. This foundational disagreement explains why spiritual dimensions are not merely underemphasized but actively excluded; they are deemed non-existent or irrelevant within the materialist paradigm.

Quantitative Analysis: Documenting the Exclusion in Research

A review of current literature and research trends reveals a significant lack of integration between technological and spiritual perspectives. This gap is quantifiable in research focus, funding, and clinical application.

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence of the Spiritual Gap in Technological Research

| Area of Analysis | Focus of Mainstream Tech/AI Research | Research Integrating Theological Perspectives | Key Indicator of Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Identity | Cognitive enhancement, memory backup, mind uploading as information transfer [9] [10]. | Limited discussion of the soul, relational personhood, and theosis (divinization) [2] [9]. | Absence of non-materialist anthropologies in technical literature. |

| Suffering & Finitude | Elimination of suffering, defeat of aging and death via cryonics, anti-aging therapies [8] [10]. | Theological exploration of suffering's potential meaning and acceptance of natural life cycles [8]. | Dismissal of redemptive suffering as an "antiquated view" [8]. |

| Purpose of Medicine | Enhancement, radical life extension, and optimization of human capabilities [12] [10]. | Healing, wholeness, and care within the context of a finite life [2] [13]. | Marginalization of "healing" as a goal in favor of "augmentation." |

| Ethical Foundations | Principle-based (autonomy, beneficence) and consequence-based utilitarianism [7]. | Virtue ethics, divine command, and the pursuit of holiness and love (Agape) [8] [2]. | Lack of theological voices in AI ethics boards and tech policy design. |

The exclusion is further evidenced by the practical trajectory of technology. For instance, the Swedish transhumanist movement reports tangible progress in NFC microchip implants and human-AI integration, with goals focused entirely on practical enhancement without reference to spiritual impact [12]. Forecasts for transhumanism by 2040 predict legal and social redefinitions of "human" based solely on technological integration, with any backlash categorized as "moral panic" from religious sectors, thereby framing spiritual concerns as irrational obstacles to progress [10].

Experimental Protocol: A Methodology for Investigating the Gap

To systematically validate the exclusion of spiritual dimensions and test the claims of theological bioethics within clinical research, the following experimental protocol is proposed. This methodology is designed to generate empirical data on the impact of technological frameworks on human spirituality and well-being.

Study Design

- Title: A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Neurotechnology-Assisted Meditation and Spiritual Experience.

- Objective: To quantify the qualitative differences in spiritual experiences between traditional contemplative practices and technology-assisted methods (e.g., EEG neurofeedback, AI-guided meditation).

- Hypothesis: Traditional, disciplined contemplative practice will yield significantly different and subjectively "deeper" reports of spiritual experience (e.g., sense of transcendence, connection, love, and awe) compared to technology-assisted shortcuts.

Participant Groups and Intervention

- Group 1 (Traditional): Undergoes training in a established contemplative practice (e.g., Centering Prayer, Hesychasm, mindfulness of breath) for 30 minutes daily over an 8-week period. Guidance will be provided by an experienced practitioner.

- Group 2 (Tech-Assisted): Uses an AI-guided meditation app with integrated neurofeedback (EEG headset) for the same duration and frequency. The AI will optimize the session in real-time to induce states of "calm" or "focus" based on biometric data.

- Control Group: Engages in a period of quiet reading of neutral material for the same duration.

Data Collection and Analysis

- Quantitative Measures: Pre- and post-intervention fMRI scans to map default mode network (DMN) activity; standardized psychological scales for mindfulness (Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire) and self-transcendence (Temperament and Character Inventory).

- Qualitative Measures: In-depth, structured interviews conducted post-intervention focusing on the nature of the participants' experiences, using terms like "connection," "gift," "effort," "love," and "presence." Thematic analysis will be applied to the interview transcripts.

- Statistical Analysis: ANOVA will be used to compare quantitative changes between groups. Qualitative data will be coded and analyzed for emergent themes related to spiritual depth and relationality.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental design:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for investigating technology's impact on spiritual experience.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Investigating Technology-Spirituality Interface

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| 64-Channel EEG System with Neurofeedback Suite | To provide real-time biometric data and enable the technology-assisted intervention for Group 2. Measures brainwave patterns associated with meditative states. |

| AI-Guided Meditation Software | The algorithmic core of the tech-assisted intervention. It adapts audio guidance and feedback based on the user's EEG data to optimize for pre-defined states like "calm." |

| 3T fMRI Scanner | To capture high-resolution images of brain activity pre- and post-intervention. Crucial for comparing neurological correlates of different practices, particularly changes in the Default Mode Network (DMN). |

| Validated Psychometric Scales (e.g., FFMQ, TCI) | To provide quantitative, standardized measures of subjective constructs like mindfulness, self-transcendence, and personality traits. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Protocol | To gather rich, qualitative data on the subjective quality, meaning, and relational aspects of the participants' experiences, which quantitative data alone cannot capture. |

Theological Bioethics as a Corrective Framework

Theological bioethics offers robust conceptual frameworks to address the gaps identified in transhumanism and AI. Its validation in clinical research is not a retreat to obscurantism but a necessary step toward a more holistic and human-centered technological future.

The Concept of the Human Person: Against the transhumanist view of the body as a upgradeable machine, theological bioethics posits a holistic anthropology. Catholic teaching, for example, emphasizes hylomorphism—the body and soul as an integral unity [8]. This view sees the body not as a prison for the soul but as a constitutive part of human identity. Similarly, Orthodox bioethics distinguishes between the "image" of God (the donum of intellect and will) and the "likeness" of God (the potential for theosis, or divinization), affirming a human nature that is both given and with a dynamic potential for growth in holiness [2]. This directly challenges the transhumanist project of self-designed post-humanity.

The Meaning of Suffering and Finitude: Transhumanism identifies suffering and death as unqualified evils to be eradicated. In contrast, theological traditions, while affirming the goodness of healing, also acknowledge the potential redemptive meaning of suffering [8]. Pope John Paul II's Salvifici Doloris teaches that suffering, when united with Christ's passion, can be a site of spiritual growth and communion [8]. This perspective reframes the goal of medicine from the total elimination of suffering to its alleviation and the finding of meaning within it, fostering virtues like compassion, patience, and solidarity [8].

Agape vs. Algorithm as a Foundation for Ethics: The dominant ethical models in AI and technology are utilitarianism and principlism, which lack a robust account of love and self-sacrifice. Theological bioethics centers on disinterested, self-giving love (Agape) [2]. This love is not a mere emotion but a fundamental orientation that sees medicine not just as a profession but as a mission of brotherly and sisterly care [2]. This stands in stark contrast to the "Dataism" described by Harari, which reduces human relationships and values to data patterns and algorithmic optimization [9].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual conflict between these worldviews:

Diagram 2: Logical conflict between technological and theological paradigms.

The investigation reveals a profound and systematic exclusion of spiritual dimensions from the core frameworks of transhumanism and AI. This gap is not accidental but stems from a materialist and reductionist worldview that is incapable of accounting for the full reality of human personhood, including consciousness, qualitative experience, love, and the quest for transcendent meaning [11] [9]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this creates a blind spot, potentially leading to technologies that augment human capacities while eroding the very qualities that make life worth living.

Validating theological bioethics in clinical practice research is therefore an urgent task. It requires moving beyond a dialogue of the deaf and actively designing experiments, like the one proposed here, that can empirically test the claims of spiritual traditions about human nature and flourishing. The goal is not to halt technological progress but to guide it with the wisdom of traditions that have reflected deeply on human dignity, purpose, and destiny for millennia. As Holmes Rolston warned, "the religion that is divorced from science today will leave no offspring tomorrow" [14]. The inverse is equally true: a science and a technological ethos divorced from spiritual wisdom may create a future that is technologically sophisticated but spiritually barren. The integration of these domains is essential for a future that is both advanced and truly human.

The integration of theological anthropology into biomedical ethics provides foundational perspectives on human value, finitude, and reasoning that remain critically relevant to clinical practice and research. This guide compares three core theological concepts—human dignity, vulnerability, and the noetic effects of sin—examining how they contribute to a comprehensive framework for bioethical deliberation. These concepts offer distinct yet complementary resources for addressing perennial challenges in healthcare ethics, from end-of-life decisions to equitable research practices. Rather than presenting competing alternatives, these theological constructs form an integrated analytical toolkit for examining the philosophical underpinnings of clinical practice and research ethics. Their validation emerges through consistent application across diverse biomedical contexts, from inpatient care to research ethics committees, where they provide robust accounts of human value amidst biological fragility and cognitive limitation.

Conceptual Frameworks & Comparative Analysis

Theological Foundations of Human Dignity

Table 1: Conceptualizations of Human Dignity in Theological Bioethics

| Concept Type | Theological Foundation | Key Characteristics | Practical Implications in Healthcare |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Dignity | Imago Dei (creation in God's image); inviolable and unconditional [15] [16] | Universal, inherent, non-contingent on capacities; equal across all persons | Requires respect for every patient regardless of clinical condition or cognitive status |

| Attributed Dignity | Human interpretation of worth based on qualities or achievements [16] | Socially constructed, variable, context-dependent | Recognizes importance of social honor while critiquing its potential biases |

| Inflorescent Dignity | Process of becoming through divine relationship; "likeness" to God [16] | Developmental, flourishing-oriented, dependent on conditions | Supports rehabilitative and palliative approaches that enable personal flourishing |

The theological concept of human dignity presents a robust alternative to autonomy-based ethical frameworks predominant in secular bioethics. Grounded primarily in the concept of imago Dei (creation in God's image), theological approaches understand dignity as an inviolable characteristic that is "donated graciously and creatively to all bearers of imago Dei" [15]. This foundation establishes human dignity as "absolute" and "independent of autonomy, rationality, or capability" [15], providing an ethical warrant for protecting vulnerable populations who might be marginalized in capacity-based ethical systems.

This theological understanding contrasts with secular approaches that frequently equate dignity with autonomy or rational capacity. The Swiss assisted-dying organization Dignitas, for example, employs the language of dignity while operating with an underlying definition that essentially reduces to personal autonomy [15]. Theological frameworks resist this reduction, instead locating human worth in the creative act of God and the incarnation of Christ, which confers dignity unconditionally on all human beings [17] [16]. This perspective proves particularly significant in end-of-life care, dementia care, and disability ethics, where cognitive or physical impairment might otherwise undermine ethical standing.

Vulnerability as Layered and Contextual

Table 2: Approaches to Vulnerability in Bioethics

| Framework | Understanding of Vulnerability | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Approach | Fixed characteristic of specific subpopulations [18] | Clear identification of at-risk groups | Risk of stereotyping; overlooks contextual factors |

| Layered Approach (Luna) | Relational, dynamic, and multi-dimensional [18] | Accounts for complexity; identifies modifiable factors | Requires more nuanced ethical analysis |

| Philosophical Accounts | Universal human condition with physical, emotional, and cognitive dimensions [19] | Comprehensive view of human experience | May overlook specific heightened vulnerabilities |

Contemporary theological bioethics has developed sophisticated approaches to human vulnerability that resist essentializing or stigmatizing interpretations. Florencia Luna's layered approach conceptualizes vulnerability as "relational and dynamic" rather than as a fixed property of certain individuals or groups [18]. This framework identifies vulnerability as emerging through the interaction between internal dispositions and external "trigger conditions" that actualize latent vulnerabilities [18]. This approach helps explain how vulnerabilities can compound through "cascading effects," where one form of vulnerability exacerbates or generates additional vulnerabilities [18].

Theological perspectives enrich this understanding by framing vulnerability as an intrinsic aspect of human finitude and embodiment rather than merely a problem to be eliminated. Philosophical accounts further distinguish between physical, emotional, and cognitive vulnerability, noting that all represent "a state of physical, emotional, and cognitive stability that is in danger of being disturbed or destroyed due to being susceptible to destabilizing influences" [19]. In healthcare contexts, these vulnerabilities become particularly salient as patients confront illness, institutional settings, and complex decision-making [19]. A theological approach acknowledges these vulnerabilities while simultaneously affirming the enduring dignity of the vulnerable person.

Noetic Effects of Sin on Ethical Reasoning

The Reformed theological concept of the "noetic effects of sin" describes how sin distorts human intellectual capacities, including ethical reasoning [20]. The term "noetic" derives from the Greek noētikos ("intellectual"), referring to how sin "sabotages our intellectual lives" [20]. This distortion operates at two levels: it affects both the "object known" (the ethical issue under consideration) and the "personal subject" (the moral reasoner) [20].

This concept explains why even carefully reasoned ethical analyses may systematically exclude or distort morally salient considerations, particularly regarding "core issues at the center of the human condition" [20]. The noetic effects of sin are especially potent in bioethical debates that touch on fundamental anthropological questions about human nature, dignity, and the limits of human agency. These effects manifest through cultural, psychological, economic, and ideological influences that shape ethical deliberation, often in ways that remain opaque to the reasoner themselves [20]. Understanding these dynamics fosters intellectual humility and underscores the value of dialogical approaches to bioethics that incorporate diverse perspectives to mitigate individual and cultural blind spots.

Interrelationship of Core Concepts: Diagrammatic Representation

The diagram above illustrates how these three core concepts interrelate within a comprehensive theological bioethics framework. Human dignity provides the foundational principle that grounds moral consideration, while the recognition of vulnerability identifies specific moral claims and obligations. The noetic effects of sin introduce an essential critical principle that qualifies all ethical reasoning, encouraging intellectual humility and procedural safeguards. Together, these concepts generate bioethical reasoning enhancements that inform specific practical applications in clinical practice and research.

Experimental Protocols & Research Methodologies

Dignity Impact Assessment Protocol

Objective: Systematically evaluate how clinical protocols or research methodologies affect patient dignity across multiple dimensions.

Methodology:

- Instrument Development: Create assessment tools measuring intrinsic, attributed, and inflorescent dignity using validated scales [16].

- Multi-dimensional Mapping: Document how specific clinical interventions affect each dignity dimension through patient interviews, structured observation, and staff surveys.

- Trigger Analysis: Identify specific aspects of clinical environments or procedures that undermine dignity, with particular attention to populations with layered vulnerabilities [18].

- Intervention Design: Develop and test dignity-conserving practices targeting identified vulnerabilities.

Validation Metrics: Pre/post-intervention dignity scale scores; patient satisfaction measures; staff awareness and attitude assessments; analysis of ethical complaints or incidents.

Vulnerability Layering Analysis Framework

Objective: Identify and address layered vulnerabilities in research populations using Luna's framework.

Methodology:

- Contextual Assessment: Document internal and external factors creating vulnerability dispositions in potential research populations [18].

- Trigger Identification: Analyze research protocols for elements that might activate latent vulnerabilities (e.g., complex consent forms, power differentials, economic incentives) [18].

- Cascading Effect Projection: Model how initial vulnerabilities might generate additional vulnerabilities throughout research participation.

- Mitigation Strategy Development: Design targeted protections for identified vulnerability layers, emphasizing autonomy preservation rather than blanket exclusion [18].

Validation Metrics: Successful recruitment of vulnerable populations without exploitation; participant comprehension metrics; protocol adherence rates; post-study participant feedback.

Cognitive Bias Audit for Research Ethics Committees

Objective: Identify and mitigate the noetic effects of sin in ethical review processes.

Methodology:

- Deliberation Analysis: Document ethical review discussions using standardized coding frameworks to identify patterns of unexamined assumptions or systematic blind spots [20].

- Stakeholder Perspective Integration: Incorporate patient, community, and interdisciplinary viewpoints to challenge disciplinary or cultural biases.

- Counterfactual Reasoning: Employ "red team" exercises where members specifically argue against provisional approvals to test robustness of ethical reasoning.

- Reflective Practice Implementation: Introduce structured reflection on how reviewers' own backgrounds, interests, and ideologies might shape ethical evaluations [20].

Validation Metrics: Diversity of perspectives in ethical discussions; documentation of considered counterarguments; tracking of dissenting opinions; post-decision outcome evaluation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents for Theological Bioethics

Table 3: Essential Conceptual Resources for Theological Bioethics Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Imago Dei Framework | Provides foundation for universal human dignity independent of capacity or function [15] [17] | Grounding research ethics; protecting vulnerable populations; resisting quality-of-life determinations |

| Layered Vulnerability Analysis | Identifies contextual and interacting vulnerability factors beyond categorical approaches [18] | Research ethics protocol development; equitable participant selection; clinical trial design |

| Noetic Effects Audit | Critical tool for identifying cognitive biases and systematic blind spots in ethical reasoning [20] | Research ethics committee deliberations; clinical ethics consultation; policy development |

| Dignity Typology Matrix | Distinguishes between intrinsic, attributed, and inflorescent dignity for precise ethical analysis [16] | Patient care quality assessment; evaluating institutional culture; developing dignity-conserving interventions |

| Theological Hermeneutic of Suspicion | Identifies where technological possibilities drive ethical justification rather than ethical reasoning guiding technology [20] [21] | Emerging technology assessment; clinical innovation oversight; policy development for novel interventions |

Comparative Performance & Research Applications

Theological frameworks demonstrate distinctive strengths when applied to complex bioethical challenges in clinical research environments. The concept of intrinsic dignity grounded in imago Dei provides particularly robust protection for vulnerable research populations, including those with cognitive impairment, neonates, and other groups frequently marginalized in capacity-based ethical systems [15] [17]. This approach resists utilitarian calculations that might sacrifice individual protection for collective knowledge advancement.

The layered model of vulnerability enables more nuanced ethical oversight than traditional categorical approaches to vulnerability in research ethics [18]. By recognizing how vulnerabilities interact and cascade in specific contexts, this framework supports more precise safeguards that protect without unjustly excluding populations from research participation and potential benefit [18]. This approach facilitates the ethical inclusion of populations with complex vulnerability profiles rather than invoking blanket exclusion.

The concept of the noetic effects of sin provides a unique critical tool for examining the ethical reasoning process itself [20]. This theological principle anticipates and explains how even sophisticated ethical deliberation can systematically exclude morally salient considerations, particularly when addressing questions with significant anthropological implications. Research ethics committees applying this principle demonstrate enhanced capacity to identify cultural, ideological, and economic biases that might otherwise distort ethical analysis.

These theological resources prove particularly valuable when addressing emerging biotechnologies that challenge traditional ethical categories. By providing stable anthropological foundations while acknowledging human cognitive limitations, this integrated framework supports both principled analysis and appropriate humility in navigating novel ethical challenges across the clinical research continuum.

The contemporary healthcare landscape is marked by a critical tension between technological advancement and the preservation of humane treatment. This analysis objectively examines two competing "products" in healthcare delivery: the dehumanizing care model, characterized by fragmented, impersonal treatment, and the comprehensive care model, which prioritizes holistic, patient-centered approaches. The investigation is framed within an emerging paradigm that validates theological bioethics as a framework for clinical practice research, offering a moral architecture for understanding human dignity in healthcare contexts. Theological bioethics, rooted in the concept that human life possesses inherent dignity as a "precious gift from God" [2], provides critical standards for evaluating these competing approaches. This comparison utilizes empirical data to assess performance metrics including patient outcomes, therapeutic relationships, and systemic efficiency, offering evidence-based insights for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals dedicated to optimizing healthcare delivery systems.

Dehumanization in Healthcare: Mechanisms and Impacts

Dehumanization in healthcare represents a systematic failure to recognize the full humanity of patients, transforming them from persons into cases, diseases, or administrative tasks. Research reveals that dehumanization operates on a spectrum from blatant to subtle forms, with patients implicitly denied fundamental human qualities like rationality, self-control, and complex emotions [22]. This phenomenon is not merely an interpersonal issue but is often structured into healthcare systems through excessive workloads, bureaucratic procedures, and technologically-mediated interactions that reduce patients to their diagnoses.

Functional and Structural Causes of Dehumanization

- Emotional Regulation Strategy: Healthcare professionals may unconsciously dehumanize patients as a coping mechanism to manage the emotional distress of constantly witnessing suffering and pain. This emotional regulation strategy helps providers avoid burnout but at the cost of empathetic connection [23].

- Task-Oriented Focus: Medical training often emphasizes diagnostic efficiency through a narrow focus on specific body parts or diseases, potentially at the expense of viewing the patient as a whole human being. This functional dehumanization may increase diagnostic effectiveness but damages the therapeutic relationship [23].

- Structural and Organizational Factors: Excessive workloads, insufficient staffing, and administrative burdens create environments where professionals are treated as "interchangeable cogs in an industrial machine," leading to cascading dehumanization of patients [22]. The "black-box" nature of increasingly integrated AI systems further risks depersonalizing healthcare by prioritizing data-driven decisions over empathetic, personalized care [24].

Documented Consequences of Dehumanized Care

The impacts of dehumanization extend beyond subjective patient dissatisfaction to measurable clinical outcomes:

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Dehumanization on Patient Outcomes

| Impact Category | Specific Consequences | Affected Populations |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Outcomes | Reduced treatment adherence, relapse in substance use disorder, poorer health outcomes [23] | All patients, particularly those with chronic conditions |

| Therapeutic Relationship | Reduced patient satisfaction with care, poorer communication [23] | All patient demographics |

| Psychological Effects | Increased sadness, shame, self-consciousness, lower self-esteem [23] | Patients with visible stigmas or mental health conditions |

| Self-Perception | Internalized dehumanization (self-dehumanization) associated with self-harm behaviors and reduced social interaction [23] | Patients with severe alcohol use disorders, mental health conditions |

| Decision-Making | Undermined patient autonomy and informed decision-making [23] | All patients, particularly evident in vulnerable populations |

The negative effects of dehumanization are particularly pronounced among patients with mental illness, who face "additive or cumulative dehumanization" that contributes to documented health inequities [23]. These patients are often dehumanized more blatantly than some vilified ethnic or religious minorities, demonstrating how diagnostic labels can trigger profound denial of human attributes [22].

Comprehensive Care Models: Evidence and Outcomes

In contrast to dehumanizing approaches, comprehensive care models explicitly address the whole person through integrated, multidisciplinary interventions. These models operationalize the principles of theological bioethics, which emphasizes that "the principal values of any human activity should always be man and life" [2], and that Christian justice demands "all people are equal whether they are rich or poor, and that they have an equal right to treatment" [2].

Experimental Evidence from Comprehensive Care Implementation

A rigorous observational study conducted at a public tertiary hospital in Mexico evaluated a six-month medium-intensity comprehensive care program for obesity (Programa de Atención para el Paciente con Obesidad, PAPO) that incorporated medical, nutritional, psychological, and psychiatric components [25]. The study design and outcomes offer compelling evidence for the efficacy of comprehensive approaches:

Table 2: Outcomes from Comprehensive Obesity Care Program (n=661 completers)

| Program Metric | Result | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Retention Rate | 65% completed program | N/A |

| Average Visits Attended | 4.9 ± 1.9 visits each | N/A |

| Participants Achieving ≥5% Weight Loss | 40.1% | p < 0.01 |

| Average Weight Decrease | Δ = -4.8 kg | p < 0.01 |

| BMI Reduction | -2.3 kg/m² | p < 0.01 |

| Odds Ratio for ≥5% Weight Loss per Additional Visit | OR 1.90, 95% CI: 1.51-2.38 | p < 0.001 |

| Odds Ratio for ≥10% Weight Loss per Additional Visit | OR 2.45, 95% CI: 1.49-4.02 | p < 0.001 |

The demonstrated dose-response relationship between program engagement and outcomes underscores the importance of sustained therapeutic relationships in comprehensive care models. Each additional visit significantly increased the likelihood of achieving clinically meaningful weight loss targets, with effects becoming statistically significant after attending more than four visits [25].

Protocol for Humanizing Care Intervention

An ongoing observational study protocol in southern Spain examines the implementation of a humanization plan across relational, structural, and organizational dimensions [26]. This multi-year investigation employs a comprehensive methodology:

Study Design: Three-year multiphase approach combining cross-sectional designs, qualitative-quantitative analyses, and psychometric assessments.

Population: Patients admitted to multiple hospitals in southern Spain along with nursing professionals.

Key Dimensions Assessed:

- Relational Dimension: Therapeutic relationships, empathetic communication

- Structural Dimension: Staffing levels, resource allocation, equipment and facilities

- Organizational Dimension: Tailored protocols, clinical pathways, interdisciplinary collaboration

Outcome Measures: Health outcomes including adverse events, readmissions, mortality rates, safety, well-being, staff outcomes including burnout, job satisfaction, and intention to leave [26].

This research hypothesizes that improvement across these three dimensions will positively impact health outcomes while facilitating economic efficiency and user satisfaction - essentially creating a healthcare system that aligns with theological bioethics' emphasis on human dignity and the concept of medicine as "a mission rather than a profession" [2].

Theological Bioethics: A Framework for Integration

Theological bioethics provides a crucial conceptual framework for understanding the moral implications of dehumanization and the validation of comprehensive care models. Grounded in the conviction that human beings are created in God's image with inherent dignity, this perspective offers distinctive insights for clinical practice research.

Core Principles of Theological Bioethics

- Sanctity of Life: Contrary to quality-of-life paradigms that may justify dehumanizing practices, theological bioethics maintains that life itself is "a precious gift from God" which must be "developed and preserved by people, who have never been masters of life but rather its servants" [2].

- Agape Love as Foundation: Christian bioethics centers on self-giving love (agape), framing medicine as a vocation rather than merely a profession. This love "would never cause any discrimination among patients, but would rather care for whole life and life of all" [2], directly countering dehumanizing tendencies.

- Justice and Equity: Theological bioethics emphasizes distributive justice in healthcare, insisting that "all people are equal whether they are rich or poor, and that they have an equal right to treatment" [2]. This principle challenges systemic dehumanization that disproportionately affects marginalized populations.

- Human Freedom and Dignity: Catholic bioethics particularly emphasizes freedom as "the base of man's dignity," recognizing patients as autonomous beings with fundamental rights to participate in healthcare decisions [2].

Orthodox Christian Contributions

Orthodox bioethics offers additional dimensions through its distinction between the "image" and "likeness" of God in human persons. The "image" represents the donum of intellect, emotion, ethical judgment, and self-determination, while the "likeness" constitutes the human potential to become Godlike through ever-expanding perfection [2]. This theological anthropology provides a robust foundation for opposing dehumanization while supporting comprehensive approaches that address the full person.

Comparative Analysis: Dehumanization versus Comprehensive Care

Direct comparison of dehumanizing and comprehensive care models reveals stark contrasts in underlying mechanisms, outcomes, and alignment with ethical frameworks:

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Care Models Across Critical Domains

| Domain | Dehumanizing Care Model | Comprehensive Care Model |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Relationship | Reduced to transactional interactions | Central, continuous, and empathetic |

| Patient View | Fragmented into symptoms or diagnoses | Holistic person with biological, psychological, social dimensions |

| Emotional Approach | Avoidance through detachment | Engagement through empathetic connection |

| Structural Support | Excessive workloads, limited resources | Appropriate staffing, balanced workloads |

| Health Outcomes | Reduced adherence, poorer outcomes, increased disparities | Improved clinical metrics, greater satisfaction, reduced disparities |

| Ethical Foundation | Utilitarian, efficiency-focused | Principle-based, dignity-oriented |

The diagram below illustrates the contrasting pathways and outcomes of these two approaches:

Contrasting Pathways of Dehumanizing versus Comprehensive Care Models

Researchers investigating dehumanization and comprehensive care models require specialized methodological tools and assessment instruments:

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Studying Dehumanization and Comprehensive Care

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Humanization Assessment Tools | Measure relational, structural, and organizational dimensions of humanized care | Evaluating hospital care quality and patient experience [26] |

| Dehumanization Scales | Assess explicit and implicit denial of human attributes to patients | Identifying subtle dehumanization in clinical settings [22] |

| Person-Centered Care Model (McCormack & McCance) | Framework for humanistic care with moral component through relationships | Implementing ideals of humanistic care in organizational structures [26] |

| Fundamentals of Care Framework (Kitson et al.) | Conceptual model acknowledging centrality of nurse-patient relationship | Addressing integration of care and context of care [26] |

| Comprehensive Program Evaluation Metrics | Assess retention, engagement, and clinical outcomes in complex interventions | Evaluating real-world implementation of comprehensive care models [25] |

| Theological Bioethics Frameworks | Provide moral architecture for understanding human dignity in healthcare | Analyzing ethical dimensions of care models and their impact on human dignity [2] [7] |

The comparative analysis between dehumanizing and comprehensive care models demonstrates a clear divergence in clinical outcomes, patient experiences, and ethical alignment. Empirical evidence establishes that comprehensive care approaches yield superior results across critical metrics including treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Meanwhile, dehumanizing practices, whether structural or interpersonal, generate demonstrable harm including reduced adherence, psychological distress, and exacerbated health disparities.

Theological bioethics provides a vital framework for validating comprehensive care models, offering a robust conceptual foundation grounded in human dignity, agape love, and justice. This moral architecture aligns with growing empirical evidence supporting person-centered, holistic approaches to healthcare. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the importance of developing and implementing healthcare interventions that honor the full humanity of patients while achieving superior clinical outcomes.

Future research directions should include more direct assessment of dehumanization in healthcare settings, improved understanding of dehumanization relative to emotion regulation processes, and continued development of comprehensive care models that address the needs of vulnerable populations, particularly those with mental illness and comorbid conditions [23]. Through such investigations, the healthcare community can systematically address dehumanization while advancing care models that truly serve the whole person.

Methodological Frameworks for Integrating Theology into Clinical and Research Ethics

For researchers and scientists in the drug development sector, bioethical dilemmas present unique challenges that demand robust, defensible frameworks for decision-making. Within Christian traditions, the approach often termed "Biblicism"—the direct application of specific biblical injunctions to contemporary moral questions—faces significant limitations when addressing novel technologies and research paradigms that did not exist in biblical times [27]. This methodological weakness becomes particularly acute in biomedical contexts, where issues like germ-line genetic intervention, cryopreservation, or nanotechnology require ethical guidance that biblical texts do not explicitly address [27].

The search for a viable ethical methodology is not merely an academic exercise but a pressing need for professionals navigating complex research environments. When scholars attempt to apply biblical texts directly to issues about which the Bible is silent, they risk either misusing Scripture or importing alien methods and influences to fill the methodological gap [27]. This paper compares the limitations of simplistic Biblicism with more robust theological frameworks that offer greater utility for clinical practice and research contexts, examining their respective capacities to address the unique ethical challenges emerging in the "Biotech Century" [28].

Methodological Frameworks: A Comparative Analysis

The Biblicist Approach: Limitations and Critiques

The Biblicist approach to bioethical dilemmas typically involves seeking direct biblical citations relevant to the issue at hand. This method works sufficiently for many traditional moral questions but reveals profound limitations when confronting novel biotechnologies [27]. Evangelical scholars have noted that this approach becomes problematic when addressing issues such as stem cell research, cloning, cybernetics, gene patenting, and other scientific developments that could not have been addressed in the Bible [27].

When explicit biblical guidance is unavailable, proponents of Biblicism may inadvertently resort to several problematic methodological approaches:

- Dubious textual interpretation: Applying biblical texts that speak only indirectly to the issue at hand [27]

- Methodological incoherence: Importing frameworks from other traditions without proper philosophical, theological, and ecclesiological context [27]

- Non-rational foundations: Basing positions on gut instinct, political loyalties, or self-interest rather than developed ethical reasoning [27]

These methodological weaknesses potentially undermine the credibility of faith-based bioethics in scientific and research contexts, where logical consistency and evidential support are paramount.

Emerging Frameworks: Principles and Theological Motifs

In response to these limitations, more sophisticated methodological approaches have emerged that engage Scripture at the level of theological principles and broad theological motifs rather than seeking direct moral injunctions [27]. This represents a movement from the level of particular moral judgments to deeper structures of moral reasoning encompassing rules, principles, and basic convictions or worldview commitments [27].

Table 1: Levels of Moral Reasoning in Theological Bioethics

| Level of Reasoning | Description | Example in Bioethics |

|---|---|---|

| Particular Moral Judgments | Decisions about specific cases or situations | Whether to participate in a specific stem cell research protocol |

| Moral Rules | Concrete action-guides for relevantly similar cases | "Do not exploit vulnerable populations in research" |

| Moral Principles | Broader, more general norms that ground rules | Respect for persons, justice, beneficence |

| Basic Convictions/Worldview | Fundamental beliefs about ultimate reality and human nature | Doctrines of creation, humanity, sin, and salvation |

This multi-layered approach enables bioethicists to develop frameworks that maintain theological integrity while engaging complex scientific contexts. Rather than looking for what is not in the Bible, scholars are forced back from the moral injunction level to other types of scriptural moral resources [27].

Experimental Philosophical Bioethics: A Bridge Framework

Conceptual Foundations and Methodology

An emerging sub-field known as experimental philosophical bioethics (bioxphi) offers promising methodological approaches for validating theological frameworks in clinical practice and research [29]. This discipline adopts the methods of experimental moral psychology and cognitive science to understand the eliciting factors and underlying cognitive processes that shape people's moral judgments about real-world bioethical concerns [29].

Bioxphi seeks to contribute to three main aims:

- Studying a wider range of stakeholder judgments beyond those of professional philosophers and bioethicists [29]

- Investigating how these judgments function in ecologically valid contexts that resemble clinical or real-life situations [29]

- Developing a richer understanding of the underlying cognitive processes and eliciting factors that shape moral judgments [29]

This methodological approach is particularly valuable for theological bioethics as it provides empirical tools for investigating how religious commitments actually function in moral decision-making across diverse contexts.

Experimental Protocols and Research Design

Bioxphi employs rigorous experimental protocols to investigate moral cognition in bioethical contexts. The following diagram illustrates a typical experimental workflow in this field:

The experimental approach typically employs consultative methods that involve collecting empirical data relating to stakeholder views, attitudes, and experiences, then using these as a basis for drawing normative conclusions [29]. The end goal is often the achievement of coherence between stakeholder data and broader considerations, including background theories, moral principles, expert intuitions, morally relevant facts, and considered judgments—a process termed wide reflective equilibrium [29].

Table 2: Bioxphi Research Strategies for Normative Inference

| Strategy | Description | Application to Theological Bioethics |

|---|---|---|

| Parsimony | Preferring explanations that require fewer ad hoc assumptions | Testing whether theological principles provide more coherent explanations than secular frameworks |

| Debunking | Identifying problematic origins of moral judgments | Examining whether judgments are based on relevant theological principles or extraneous factors |

| Triangulation | Using multiple methods to investigate the same phenomenon | Combining survey, qualitative, and experimental approaches to moral cognition |

| Pluralism | Acknowledging multiple valid perspectives while maintaining normative commitments | Understanding how different theological traditions address common bioethical challenges |

Theological Frameworks for Bioethical Reasoning

Principles for Religious Accommodation in Bioethics

In pluralistic research and clinical environments, frameworks for religious accommodation must balance claims of religious liberty with claims to equal treatment in health care [30]. Several mid-level principles have been proposed to guide such accommodation in biomedical contexts [30]:

- Principle of Respect for Conscience: Protecting the integrity of individual moral convictions

- Principle of Professional Responsibility: Defining the core obligations of healthcare and research professionals

- Principle of Public Reason: Ensuring that policy justifications are accessible to all citizens

- Principle of Civic Hospitality: Creating space for religious expression within civic institutions

These principles function as prima facie guidelines rather than absolute rules, requiring careful interpretation and balancing in specific contexts [30]. For drug development professionals, such frameworks offer resources for navigating conflicts between religious commitments and professional responsibilities in increasingly secular and pluralistic environments [31].

Natural Law and Theological Anthropology

Some Christian bioethicists have turned to natural law theory as a framework for ethical reasoning that maintains theological integrity while engaging pluralistic contexts [31]. Contrary to mischaracterizations, natural law in the Thomistic tradition is not an attempt to construct morality without God but represents "the rational creature's participation in the eternal law" [31].

This approach is complemented by robust theological anthropologies that inform bioethical decision-making. Orthodox Christian bioethics, for example, emphasizes the concept of humans created in God's "image" and "likeness"—where "image" represents the donum of intellect, emotion, ethical judgment, and self-determination, while "likeness" represents the human potential to become Godlike through the process of theosis or divinization [2]. This theological framework provides a foundation for ethical reasoning that acknowledges both human nature as a given and human potential for transformation and growth.

The following diagram illustrates how these theological frameworks structure bioethical reasoning:

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

The empirical investigation of theological bioethical frameworks requires specific methodological tools and approaches. The table below details key "research reagents"—conceptual and methodological resources—for conducting this interdisciplinary work:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Theological Bioethics Investigation

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ecologically Valid Scenarios | Experimental stimuli resembling real-world clinical/research dilemmas | Developing vignettes about genetic engineering decisions that mirror actual research contexts |

| Moral Judgment Measures | Quantitative and qualitative assessment of ethical evaluations | Using Likert scales and open-ended responses to assess permissibility judgments |

| Process Tracing Methods | Identifying cognitive processes underlying moral decisions | Think-aloud protocols or cognitive load manipulations during bioethical decision-making |

| Stakeholder Diversity Sampling | Ensuring representation of relevant perspectives | Including patients, researchers, ethicists, and religious adherents in studies |

| Theological Commitment Measures | Assessing the nature and strength of religious beliefs | Scales measuring doctrinal adherence, religious practice, and spiritual experiences |

| Cross-Traditional Comparison | Investigating patterns across different religious traditions | Comparing Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant responses to the same bioethical dilemma |

The movement from Biblicism to theological principles and doctrines represents a methodological maturation within Christian bioethics that enhances its capacity to contribute to contemporary clinical practice and research contexts. By developing more sophisticated frameworks that maintain theological integrity while engaging scientific complexity, bioethicists can provide resources that are both faithful to religious traditions and relevant to the challenges facing researchers and drug development professionals.

The integration of empirical methods from experimental philosophical bioethics with rich theological frameworks offers promising approaches for validating and refining ethical guidance for the "Biotech Century" [28]. This interdisciplinary approach acknowledges that while theological commitments provide essential foundational perspectives, their application to novel challenges requires careful reasoning, empirical investigation, and dialogue with multiple stakeholders in research and healthcare environments.

For scientists and researchers, these developed theological frameworks offer resources for addressing the profound human questions raised by biotechnological progress while maintaining scientific excellence and ethical integrity. As the field continues to develop, this integrative approach promises to contribute meaningfully to our collective ability to navigate the complex ethical terrain of emerging technologies while honoring the depth of religious traditions and their visions of human flourishing.

The validation of a theological bioethics framework within clinical research requires a structured comparison against prevailing secular models. This guide objectively compares their performance, supporting analysis with principles derived from Christian theology and its application in clinical settings.

Comparative Framework Analysis: Theological vs. Secular Bioethics

The table below summarizes the core principles and clinical performance of a theological framework against common secular approaches.

| Comparative Dimension | Theological Bioethics Framework | Principle-Based Secular Bioethics | Utilitarian/Consequentialist Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundational Basis | Divine revelation (Scripture), Tradition, and Reason [32] [2] | Secular philosophy (e.g., Kantian deontology) [7] | Calculation of optimal outcomes (e.g., maximum benefit) [7] |

| Concept of Human Dignity | Inherent and inviolable, derived from being created in the Imago Dei (Image of God) [32] [2] | Often inherent, but based on autonomy or rational capacity [7] | Contingent, often tied to one's quality of life or utility [2] |

| Primary Ethical Orientation | Agape (Self-giving love) and service; life as a gift to be stewarded [2] | Respect for Autonomy and individual rights [7] | Maximization of Net Benefits (e.g., for the population) [7] |

| Clinical Performance: End-of-Life Decisions | Prioritizes sacredness of life; cautions against hastening death; emphasizes palliative care as an act of love [2] [13] | Heavily influenced by patient autonomy, potentially justifying physician-assisted suicide [2] [13] | May justify withdrawal of treatment or assisted dying for resource reallocation or to end suffering [2] |

| Clinical Performance: Beginning-of-Life Issues | Protects the embryo from conception due to its potential for bearing God's image [2] [7] | Status of the embryo is debated; often tied to developmental stages or personhood theories [7] | May permit selective abortion or embryo research for potential future health benefits [2] |

| Key Strength | Provides a robust, transcendent foundation for human value and moral duties [32] [33] | Provides a common, neutral language for pluralistic settings [7] | Offers a clear, pragmatic method for resource allocation decisions |

| Key Limitation | Requires theological commitment for full acceptance; perceived as less flexible in pluralistic settings [2] | Principlism can become abstract; offers a thin account of the "good life" [7] | Can risk instrumentalizing and violating the rights of minority or vulnerable individuals [2] |

Experimental Protocol for Framework Validation

Validating a theological-ethical framework in clinical research involves assessing its applicability, coherence, and impact. The following methodology outlines a protocol for such empirical and qualitative investigation.

Study Design

- Type: Mixed-methods, multi-center study.

- Objective: To evaluate the applicability, coherence, and impact of the theological-ethical framework in real-world clinical ethical dilemmas.

- Population: Ethics committee members, clinicians, researchers, and patients from diverse institutional settings (secular, Catholic, and other Christian hospitals) [13].

Data Collection & Analysis Phases

Phase 1: Framework Application

- Method: Present identical complex case studies (e.g., involving genetic engineering, end-of-life care, resource allocation) to different ethics committees.

- Intervention: One group uses the standard principilst framework; another uses the proposed theological framework grounded in creation, anthropology, and eschatology [32] [33].

- Data Collected: Document the deliberative process, final recommendations, and reasoning.

Phase 2: Qualitative Assessment

- Method: Conduct structured interviews and focus groups with participants after Phase 1.

- Metrics: Assess perceived Internal Validity (logical coherence of the framework), Construct Validity (whether it accurately addresses the core of the ethical problem), and External Validity (its perceived applicability to broader clinical contexts) [34].

- Sample Questions: "Did the framework provide a satisfying resolution?" "Could its reasoning be explained to a patient?"

Phase 3: Outcome Measurement

- Quantitative Metrics: Track time to resolution, level of consensus among committee members, and longitudinal outcomes of the ethical decisions on patient and family well-being.

- Qualitative Metrics: Analyze interview transcripts for themes of moral distress, professional satisfaction, and the framework's capacity to navigate conflict.

Validation Criteria

The framework will be considered validated if it demonstrates:

- High Internal Validity: Consistent and logical application of core principles across diverse cases [34].

- High Construct Validity: Effectively measures and guides the resolution of the underlying theological-ethical concepts (e.g., dignity, stewardship, hope) [34].

- Meaningful External Validity: Shows adaptability and relevance across different clinical specialties and patient populations [34].

Logical Framework of Theological Bioethics

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and flow of reasoning within the proposed theological-ethical framework, from its foundational doctrines to its clinical application.

For researchers aiming to operationalize and validate this framework, the following tools and resources are essential.

| Tool/Resource | Function & Utility in Research |

|---|---|

| Scriptural & Traditional Sources | Provide the primary data and normative foundation for the framework's principles (e.g., Genesis 1:27 on Imago Dei) [32]. |