From Principles to Practice: A Practical Guide to Implementing the Belmont Report in IRB Protocols

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying the Belmont Report's ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—to Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols.

From Principles to Practice: A Practical Guide to Implementing the Belmont Report in IRB Protocols

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying the Belmont Report's ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—to Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols. It covers the historical foundation of these principles, details their methodological application in study design and consent processes, offers solutions for common challenges in risk assessment and vulnerable populations, and validates the approach by comparing it with other ethical codes like the Nuremberg Code and Declaration of Helsinki. The guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to develop ethically sound, compliant, and robust research protocols that prioritize human subject protection.

The Bedrock of Research Ethics: Understanding the Belmont Report's Core Principles

The implementation of the Belmont Report's ethical principles in modern Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols cannot be fully understood without examining the critical historical milestones that necessitated their development. The period from the post-World War II era to the 1970s witnessed a profound transformation in the ethics of human subjects research, driven primarily by the exposure of egregious ethical violations in both international and domestic research settings. This document traces the trajectory from the Nuremberg Code, developed in response to Nazi war crimes, through the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, a domestic violation that shocked the American public, to the legislative response of the National Research Act of 1974. This historical context provides the essential foundation for appreciating the moral imperative behind the Belmont Report's principles and their practical application in contemporary research oversight [1] [2].

Historical Ethical Violations and Their Principles

The Nuremberg Code (1947)

Origin and Context

The Nuremberg Code emerged from the 1947 "Doctors' Trial" of Nazi physicians who conducted brutal and deadly experiments on concentration camp prisoners without their consent [3] [4]. During the trial, the defendants argued that no clear international laws differentiated between legal and illegal human experimentation, highlighting a critical regulatory gap [3]. The American judges presiding over the case subsequently articulated a 10-point statement to define the limits of permissible medical experimentation, which became known as the Nuremberg Code [4]. While initially created in response to these specific war crimes, the Code's significance later expanded to provide ethical guidance for human experimentation in broader contexts [3].

Key Principles and Directives

The Nuremberg Code established voluntary consent as its foundational and absolute requirement. This consent must be informed, comprehending, and freely given without any element of coercion [3]. The Code further outlined that experiments should be designed to yield fruitful results for the good of society, based on prior animal testing and knowledge of the disease, and conducted so as to avoid all unnecessary suffering [3] [2]. It introduced the critical concept of a favorable risk-benefit assessment, stating that the degree of risk should never exceed the humanitarian importance of the problem to be solved [3]. Finally, it affirmed the subject's right to terminate participation and the scientist's duty to end the experiment if continuation is likely to result in injury, disability, or death [4].

Table 1: Core Principles of the Nuremberg Code

| Principle Number | Ethical Focus | Key Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Respect for Persons | Voluntary, informed, and comprehending consent is absolutely essential. |

| 2-3 | Beneficence | The experiment must yield socially valuable results, justified by prior knowledge. |

| 4-6 | Risk-Benefit Assessment | Risks must be minimized and proportionate to the humanitarian importance. |

| 9-10 | Subject and Researcher Autonomy | The subject may end participation; the scientist must terminate if risks escalate. |

The U.S. Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee (1932-1972)

Study Design and Ethical Failures

The U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee was a 40-year longitudinal study that began in 1932 with the stated aim of observing the natural history of untreated syphilis in 399 African American men with the disease and 201 without it [5] [6]. The study was fundamentally unethical from its inception. Researchers did not collect informed consent from participants, who were misled into believing they were receiving treatment for "bad blood," a local term encompassing various ailments [5] [6]. Most egregiously, researchers actively withheld effective treatment even after penicillin became the standard cure for syphilis in 1947 [5] [6]. The study continued until 1972 when it was terminated after public exposure by a news report [5].

Impact and Legacy

The Tuskegee study resulted in severe harm to its participants; by the end, 28 men had died directly from syphilis, 100 from related complications, at least 40 spouses had been infected, and the disease had been passed to 19 children at birth [6]. The subsequent public outrage led to Congressional hearings and, in 1974, a $10 million out-of-court settlement for the participants and their heirs [5] [6]. The study’s legacy is a profound and persistent mistrust of public health officials and medical research within African American communities and other marginalized groups [6]. It stands as a stark American example of the failure to adhere to the Nuremberg Code's principles, particularly regarding justice in the selection of subjects, as a vulnerable population was exploited for research [2].

Table 2: Tuskegee Syphilis Study Timeline and Consequences

| Year | Event | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1932 | Study begins | 600 African American men enrolled without informed consent. |

| 1947 | Penicillin becomes standard treatment | Researchers deliberately withhold treatment to continue observation. |

| 1972 | Associated Press exposes study | Public outrage forces the study to end. |

| 1973 | Congressional Hearings | Scrutiny of unethical research practices. |

| 1974 | Out-of-court settlement | $10 million distributed to participants and heirs. |

| 1997 | Presidential Apology | President Bill Clinton formally apologizes on behalf of the U.S. government. |

The Regulatory Response: National Research Act and the Birth of the Belmont Report

The National Research Act of 1974

The National Research Act (NRA) was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on July 12, 1974, as a direct legislative response to the public outcry over the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [7] [2]. The Act was designed to address glaring deficiencies in the oversight of research involving human subjects. Its primary provision was the creation of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [7]. This Commission was tasked with the critical mission of identifying comprehensive ethical principles and developing guidelines for the conduct of human subjects research [1].

The Belmont Report: From History to Application

The work of the National Commission culminated in 1979 with the publication of the Belmont Report [8]. This report synthesized the lessons from past ethical failures into a framework of three core principles to guide the ethical conduct of research:

- Respect for Persons: This principle acknowledges the autonomy of individuals and requires that they be provided the opportunity to make informed choices. It also mandates protection for persons with diminished autonomy [8]. This addresses the failures of both the Nazi experiments and Tuskegee by making informed consent a central requirement.

- Beneficence: This principle extends beyond "do no harm" to an obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [8] [2]. It requires a systematic assessment of risks and benefits, directly responding to the unnecessary suffering and death permitted in prior unethical studies.

- Justice: This principle requires the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [8] [2]. It specifically guards against the exploitation of vulnerable populations, a direct ethical lesson from Tuskegee where a disadvantaged group bore all the risks.

The Belmont Report also operationalized these principles by outlining their applications: Informed Consent (from Respect for Persons), Assessment of Risks and Benefits (from Beneficence), and Selection of Subjects (from Justice) [1].

Implementation Framework: Translating History into IRB Protocol

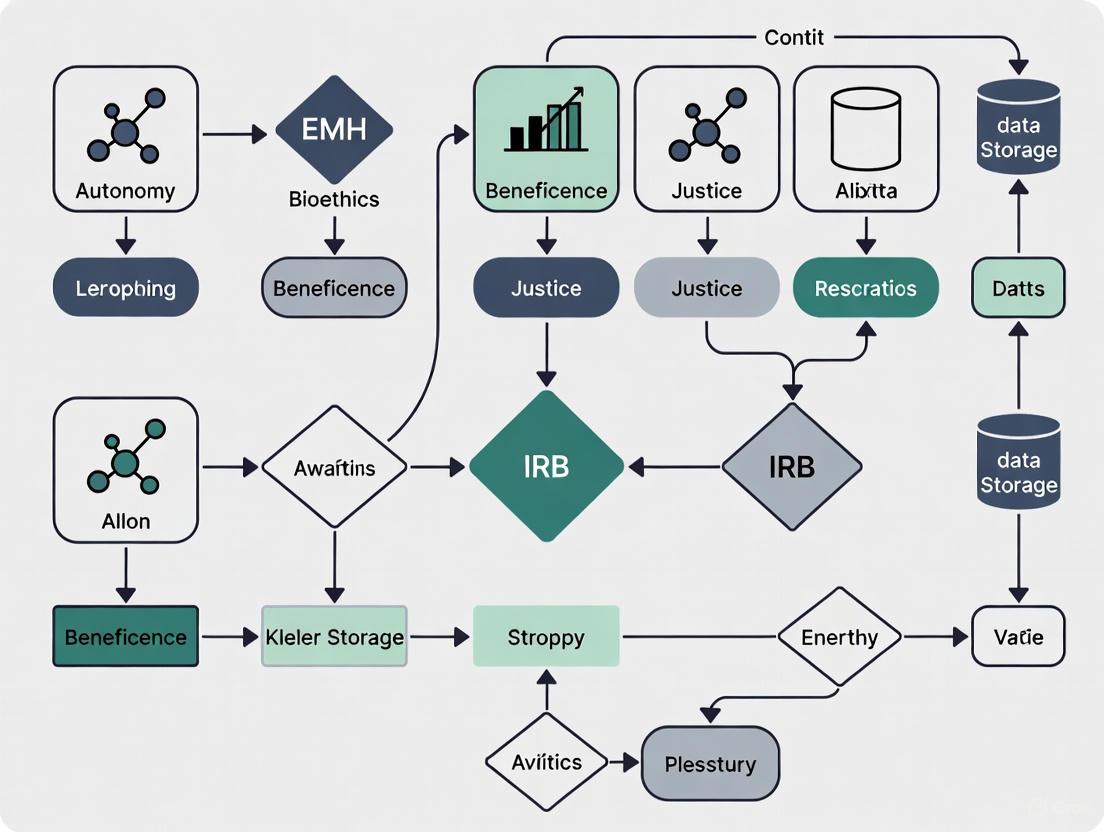

The following diagrams and tools illustrate how the historical lessons and ethical principles are systematically integrated into modern research oversight.

Logical Workflow: From Ethical Violations to Modern IRB Application

IRB Review Protocol: Operationalizing the Belmont Report

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) is the practical embodiment of the regulations stemming from the National Research Act and the ethical framework of the Belmont Report [9] [2]. An IRB is an appropriately constituted group formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects [9]. The following protocol details the application of the Belmont principles during IRB review.

Table 3: IRB Review Checklist Based on Belmont Report Principles

| Belmont Principle | Application | IRB Review Questions | Historical Context Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Informed Consent | - Is the consent process voluntary and free from coercion?- Is the information complete and comprehensible?- Are provisions made for vulnerable populations? | Addresses lack of consent in Nuremberg and Tuskegee. |

| Beneficence | Risk-Benefit Assessment | - Are risks minimized?- Are risks reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits?- Is data safety monitoring planned? | Responds to unnecessary harm in Nazi experiments and Tuskegee. |

| Justice | Subject Selection | - Are selection criteria equitable?- Are vulnerable populations targeted only for compelling scientific reasons?- Are the populations bearing the risks also likely to benefit from the research? | Counters exploitation of prisoners and African American men. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ethical Research

This toolkit outlines the essential components, derived from historical lessons, that every researcher must utilize to conduct ethical human subjects research.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Conduct

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Ethical Research | Historical Justification |

|---|---|---|

| IRB-Approved Protocol | Serves as the formal authorization to proceed with research, confirming ethical and regulatory compliance. | Mandated by the National Research Act of 1974 in response to Tuskegee. |

| Informed Consent Document | Provides the mechanism for ensuring participants understand the research and voluntarily agree to participate. | A direct response to the fundamental violation of the Nuremberg Code and Tuskegee Study. |

| Data Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP) | Outlines procedures for ongoing review of data to ensure participant safety and study integrity. | Embodies the beneficence principle, preventing unnecessary harm as seen in past unethical studies. |

| Vulnerable Population Safeguards | Additional protective procedures for participants with diminished autonomy (e.g., children, prisoners). | Addresses historical exploitation of vulnerable groups in Willowbrook and Tuskegee. |

| Certificate of Confidentiality | Protects identifiable research information from forced disclosure to entities like courts or employers. | Upholds the principle of Respect for Persons by protecting participant privacy. |

The path from the Nuremberg Code and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study to the National Research Act of 1974 and the Belmont Report represents a necessary evolution in the ethical consciousness of the scientific community. These historical events are not mere anecdotes but the foundational pillars upon which modern human research protections are built. The Belmont Report's principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice provide the indispensable ethical compass, while the IRB system, created by the National Research Act, serves as the enforcing mechanism. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of this history is not optional—it is a professional obligation. It ensures that the grave errors of the past inform a more ethical and responsible future for human subjects research.

The Belmont Report, formally published in 1979, established a foundational framework for ethical research involving human subjects in the United States [10]. It was created by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in direct response to egregious ethical violations in historical studies, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [2]. The report articulates three fundamental ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—which serve as the ethical compass for designing, reviewing, and conducting research [8] [11]. These principles are not merely theoretical concepts; they provide the underlying moral foundation for federal regulations, including the Common Rule (45 CFR 46), and form the core of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) evaluation process [11] [2]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to effectively implement these pillars within their IRB protocols and research practices.

The Historical Context and Creation of the Belmont Report

The path to the Belmont Report was paved by a history of ethical transgressions in research. Key documents like the Nuremberg Code (1947) and the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) were early attempts to establish international ethical standards [2]. However, events like the Willowbrook State School study, where children with mental disabilities were deliberately infected with hepatitis, and the Brooklyn Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital study, which involved injecting cancer cells into elderly patients without consent, highlighted the persistent vulnerability of certain populations [2]. The public revelation of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which hundreds of African-American men were left untreated for syphilis for decades without their knowledge, became the catalyst for congressional action [2].

In 1974, the U.S. Congress passed the National Research Act, which led to the creation of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [10]. This commission was tasked with identifying the comprehensive ethical principles that should govern human subjects research. The result of their work was the Belmont Report, a concise document that has endured as the cornerstone of research ethics for over four decades [1] [11].

Deconstructing the Ethical Pillars

The three principles outlined in the Belmont Report are designed to be broad and adaptable, providing a framework for analyzing the ethical considerations of research. The following table summarizes their core components and regulatory translations.

Table 1: The Three Ethical Principles of the Belmont Report

| Ethical Principle | Core Ethical Conviction | Primary Regulatory Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Individuals should be treated as autonomous agents; persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [8]. | Informed Consent; Respect for Privacy [8] [11]. |

| Beneficence | Do not harm; maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [8]. | Assessment of Risks and Benefits; Favorable Risk-Benefit Ratio [12] [8]. |

| Justice | The benefits and burdens of research must be distributed fairly [8]. | Fair Subject Selection; Equitable Recruitment [12] [10]. |

Pillar 1: Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two distinct ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to additional protections [8].

Application to Informed Consent: The primary practical application of this principle is the process of informed consent [8] [11]. This is not merely the act of signing a form, but a dynamic process of information exchange. To be valid, consent must be voluntary, competent, and informed [8]. Researchers must ensure that prospective participants make their own decision about whether to join a study based on a clear understanding of what it involves [12]. The Belmont Report specifies that subjects must be provided with all the information they need to make that decision, including the research procedures, their purposes, any potential risks and anticipated benefits, and alternative procedures [8]. They must also be given the opportunity to ask questions and must understand that they can withdraw from the research at any time without penalty [12] [8].

Protocol for Research with Vulnerable Populations: The second moral requirement of this principle obliges researchers to protect individuals with diminished autonomy. These can include children, prisoners, individuals with intellectual or cognitive disabilities, or educationally or economically disadvantaged persons [11] [2]. The protocol for such groups involves:

- Justification for Inclusion: The research protocol must provide a strong scientific justification for including these populations. It is unethical to select them merely for convenience [12] [2].

- Proxy Consent: For those who cannot provide consent for themselves (e.g., young children or adults with severe dementia), permission must be obtained from a legally authorized representative [11] [2].

- Assent: Even when proxy consent is obtained, the prospective subject's affirmative agreement (assent) should be sought to the extent they are capable. A child's dissent, for example, should generally be respected, though regulations may allow a parent's permission to override it in certain therapeutic contexts [11].

Pillar 2: Beneficence

The principle of Beneficence extends beyond simply "do no harm" to an affirmative obligation to secure the well-being of research participants [8]. This is expressed through two complementary rules: "(1) do not harm and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms" [8].

Application to Systematic Risk-Benefit Assessment: This principle requires a thorough and systematic analysis of the risks and benefits associated with the research [12] [10]. Researchers must scrutinize the study design to identify all foreseeable risks, which can be physical, psychological, social, or economic [12]. Similarly, potential benefits must be identified, which may accrue to the individual subject or to society in the form of generalized knowledge [8]. The IRB's role is to determine that the risks have been minimized to the greatest extent possible and that the remaining risks are justified by the anticipated benefits [12] [2].

Protocol for Ongoing Risk Monitoring: The ethical obligation of beneficence does not end after the initial IRB approval. It requires continuous vigilance throughout the study. The research protocol must include:

- Data and Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP): A clear plan for monitoring collected data to ensure participant safety, especially in clinical trials. This may involve an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) for higher-risk studies.

- Procedures for Adverse Events: Defined procedures for identifying, documenting, reporting, and managing any adverse events or unexpected effects that participants experience [12].

- Dissemination of New Information: A commitment to inform participants of any new information that emerges during the course of the research that might change their assessment of the risks and benefits of participating [12]. If their welfare is compromised, the protocol must ensure appropriate treatment and, when necessary, removal from the study [12].

Pillar 3: Justice

The principle of Justice demands fairness in the distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [8] [10]. It addresses the ethical concern that no single group or class of individuals should be systematically selected to bear the risks of research simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or social standing, while other, more privileged groups reap the benefits [8].

Application to Fair Subject Selection: The primary application of justice is in the recruitment and selection of research subjects [12] [11]. The scientific goals of the study must be the primary basis for recruiting participants, not vulnerability, privilege, or other unrelated factors [12]. Historically, injustices have occurred when dependent populations (e.g., prisoners, racial minorities, institutionalized patients) were selected for risky research because they were convenient or easy to manipulate [2]. Conversely, justice also requires that specific groups (e.g., women or children) should not be excluded from the opportunity to participate in and benefit from research without a sound scientific reason [12].

Protocol for Equitable Recruitment and Inclusion: To uphold justice, a research protocol must demonstrate:

- Inclusion and Exclusion Justification: All criteria for including or excluding potential subjects must be directly related to the research question and not based on race, gender, economic status, or culture alone [12] [10].

- Vulnerable Population Safeguards: If the research includes vulnerable groups, the protocol must detail the additional safeguards in place to protect their rights and welfare [2].

- Benefit Sharing: The protocol should consider whether the populations that are assuming the risks of the research are in a position to enjoy its benefits. Research on a disease that predominantly affects a specific group should, if successful, be made available to that group [12] [10].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Operationalizing the Belmont Principles

Conceptual Framework and Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the Belmont Report's ethical principles and their practical applications in the IRB review process, providing a workflow for researchers.

Belmont Principles to IRB Workflow

Essential Materials and Reagent Solutions for Ethical Research

While ethical research does not rely on physical reagents, it requires a set of conceptual tools and documented plans. The following table details these essential "research reagents" for implementing the Belmont principles.

Table 2: Essential Protocol Components for Ethical Research

| Item | Function & Purpose | Belmont Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent Document (ICD) | A comprehensive, understandable document that provides all key information about the study, allowing a potential subject to make a voluntary, informed decision [13]. | Respect for Persons |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocol | The formal application submitted for ethical review. It details the study's rationale, methodology, and, crucially, plans for subject protection [2]. | All Three Principles |

| Data and Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP) | A proactive plan for monitoring participant safety and data integrity throughout the trial. It may specify stopping rules if risks outweigh benefits [12]. | Beneficence |

| Recruitment Materials & Scripts | All advertisements, flyers, and verbal scripts used to enroll participants. These must be fair, not coercive, and approved by the IRB [12] [13]. | Justice, Respect for Persons |

| Data Anonymization/Pseudonymization Protocol | A method for protecting participant privacy by removing or replacing identifying information with codes, safeguarding confidentiality [13]. | Respect for Persons |

| Adverse Event Reporting Plan | A formal procedure for identifying, documenting, reporting to the IRB, and managing any unplanned or harmful events experienced by a participant [12]. | Beneficence |

Advanced Applications and Protocol Scenarios

Ethical Challenges in Dissemination & Implementation Research

Emerging research fields like Dissemination and Implementation (D&I) research present unique ethical challenges that require careful application of the Belmont principles [14]. These studies, which aim to integrate evidence-based interventions into routine care, often blur the lines between research and clinical practice. Key ethical questions include:

- Is it Human Subjects Research? Determining whether a D&I study qualifies as human subjects research can be complex, as some projects may be classified as quality improvement and exempt from IRB oversight, even when collecting patient-level data [14].

- Who is the Research Participant? In multilevel interventions targeting patients, clinicians, and health systems, it can be challenging to identify all research participants and determine from whom informed consent is required [14].

- Clinical Equipoise: It can be difficult to justify equipoise (genuine uncertainty about the superior intervention) in D&I studies because the intervention itself is already evidence-based. The ethical uncertainty often lies in the implementation strategy, not the intervention's efficacy [14].

Protocol Guidance: Researchers should engage with their IRB early in the design phase of D&I studies. The protocol should explicitly define all groups interacting with the research, justify the level of risk for each group, and detail a tailored consent process (which may include cluster consent or waivers of consent) that is appropriate for the study design and context [14].

Protocol: Resolving Conflicts Between Ethical Principles

The Belmont Principles can sometimes conflict with one another, requiring careful balancing by both the researcher and the IRB [11].

Scenario: Pediatric Research In research involving children, the principle of Respect for Persons (honoring the child's dissent) may conflict with Beneficence (allowing a parent to consent to a potentially beneficial therapy) or Justice (conducting research to gain knowledge for other children with the same condition) [11].

Resolution Protocol:

- Prioritize Consensus: The researcher's first duty is to facilitate a consensus between the child and parent/guardian, respecting the child's developing autonomy [11].

- Risk-Benefit Analysis:

- If the research is greater than minimal risk but offers direct benefit to the child, the IRB may allow the parent's permission to override the child's dissent to obtain that benefit (favoring Beneficence) [11].

- If the research is greater than minimal risk with no direct benefit (only generalizable knowledge for others), the IRB will generally require a higher level of protection, such as permission from both parents, to ensure the risks are reasonable in relation to the knowledge gained (favoring Justice and Beneficence over individual Respect for Persons in this specific context) [11].

The three pillars of the Belmont Report—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—provide a durable and essential framework for ensuring that the pursuit of scientific knowledge does not come at the cost of human rights or dignity. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these principles are not abstract ideals but practical guides that must be meticulously operationalized in every aspect of a study, from its initial design and IRB protocol to its final execution and dissemination of results. By systematically applying these principles through robust informed consent procedures, rigorous risk-benefit analyses, and equitable subject selection, the research community upholds its ethical integrity, maintains public trust, and ensures that scientific progress is made in a morally defensible manner.

The transition from the Belmont Report's ethical principles to the codified requirements of the Common Rule and FDA regulations represents a critical evolution in human research protections. Published in 1979 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, the Belmont Report established three fundamental ethical principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice [8]. This document emerged in direct response to ethical violations in historical studies, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where hundreds of African-American men were left untreated for syphilis without their informed consent [2] [15]. The Belmont Report provided the ethical foundation, but required regulatory force to ensure consistent application across the research landscape.

The regulatory frameworks that followed—the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (Common Rule) and the FDA's human subject regulations—operationalized these ethical principles into specific requirements for researchers, sponsors, and institutions [16] [17]. The Common Rule was first published in 1991 and has been adopted by 15 federal departments and agencies, creating a unified standard for publicly funded research [16]. Simultaneously, the FDA developed its regulations under 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56, governing clinical investigations for products under its jurisdiction [16] [17]. This application note examines how each Belmont principle was translated into specific regulatory requirements and provides practical guidance for implementation within modern Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols.

Operationalizing the Belmont Principles

Principle 1: Respect for Persons

The principle of respect for persons incorporates two ethical convictions: individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [8]. This principle recognizes the personal dignity and autonomy of individuals and requires special protection for those with diminished autonomy [18].

The regulatory frameworks translate this principle primarily through informed consent requirements and special protections for vulnerable populations. The Common Rule and FDA regulations mandate that investigators obtain legally effective informed consent from subjects or their legally authorized representatives before including them in research, with few exceptions [16] [17]. This process must include eight specific elements of information, ensuring subjects enter research voluntarily and with adequate information [8]. For vulnerable populations like children, prisoners, and individuals with diminished decision-making capacity, additional safeguards are required to protect their rights and welfare [8] [2].

Table: Translation of Respect for Persons into Regulatory Requirements

| Ethical Component | Regulatory Manifestation | Key Regulatory Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Participation | Informed consent as a process without coercion | 45 CFR 46.116; 21 CFR 50.20 |

| Adequate Information | Required elements of informed consent | 45 CFR 46.116(a); 21 CFR 50.25(a) |

| Comprehension | Consent information in understandable language | 45 CFR 46.116(a)(4); 21 CFR 50.20 |

| Special Populations | Additional protections for vulnerable groups | 45 CFR 46 Subparts B, C, D; 21 CFR 50.55-56 |

Principle 2: Beneficence

The principle of beneficence obligates researchers to secure the well-being of participants by maximizing possible benefits and minimizing possible harms [8] [2]. This principle extends beyond the medical maxim of "do no harm" to include an obligation to promote the welfare of research participants through a careful risk-benefit analysis [8].

Regulations operationalize beneficence through systematic risk assessment and requiring favorable risk-benefit ratios. IRBs must determine that risks to subjects are minimized by using procedures that are consistent with sound research design and that do not unnecessarily expose subjects to risk [19] [20]. Additionally, IRBs must assess whether risks are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result [2]. This systematic assessment ensures that the research design adequately protects participants' welfare.

Table: Beneficence Implementation in Research Oversight

| Ethical Obligation | Regulatory Implementation | IRB Review Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Assess Risks | Systematic review of all potential harms | Physical, psychological, social, economic risks |

| Maximize Benefits | Design optimization to enhance benefits | Direct benefits to subjects, societal benefits |

| Risk-Benefit Analysis | Justifiable relationship between risks and benefits | Favorable risk-benefit ratio for acceptable research |

| Ongoing Monitoring | Continuing review of approved research | Annual review, adverse event reporting |

Principle 3: Justice

The principle of justice requires that the benefits and burdens of research be distributed fairly [18] [2]. This principle addresses concerns about exploiting vulnerable populations or selectively enrolling subjects based on convenience rather than scientific reasons [8].

The Common Rule and FDA regulations implement justice primarily through equitable subject selection [19]. IRBs must ensure that subject selection is equitable by considering the purposes of the research and the setting in which it will be conducted [19]. The regulations specifically prohibit systematically selecting subjects simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or susceptibility to manipulation [8]. Special populations such as prisoners, children, and other vulnerable groups receive additional protections to prevent exploitation [17].

Regulatory Framework and Implementation

The Common Rule: Structure and Revisions

The Common Rule, formally known as the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, established uniform standards for human subjects research across federal departments and agencies [16]. Originally promulgated in 1991, the Common Rule underwent significant revisions that took effect in 2018 to address changes in the research landscape, including the growth in clinical trials, use of electronic health data, and sophisticated analysis techniques [16]. These revisions modernized the regulations to reduce burden, delay, and ambiguity while maintaining core ethical protections [16].

Key provisions of the revised Common Rule include:

- Streamlined continuing review: Elimination of annual continuing review requirements for certain minimal risk research [16]

- Expanded exemptions: New categories of exempt research based on minimal risk provisions [16]

- Single IRB review: Requirement for use of a single IRB for multi-institutional research in the United States [16] [19]

- Enhanced informed consent: New "key elements" section and rearranged content to facilitate understanding [16]

The revised Common Rule also introduced three "burden-reducing provisions" that institutions could implement early, including the revised definition of "research," allowance for no annual continuing review of certain categories, and elimination of the requirement for IRBs to review grant applications [16].

FDA Human Subject Regulations

The Food and Drug Administration regulations provide parallel but distinct oversight for clinical investigations involving products regulated by the FDA, including drugs, biological products, medical devices, and electronic products [16] [17]. While the FDA regulations share common ethical foundations with the Common Rule, there are important differences that researchers must recognize.

The FDA framework includes:

- Informed consent requirements (21 CFR Part 50): Standards for obtaining and documenting informed consent [17]

- IRB regulations (21 CFR Part 56): Standards for IRB composition, operation, and responsibility for reviewing FDA-regulated research [17]

- Investigational requirements (21 CFR Parts 312 and 812): Procedures governing use of investigational new drugs and devices [17]

Notable differences between FDA and Common Rule regulations include qualifications for exemptions and requirements for waivers of consent [16]. The 21st Century Cures Act mandates harmonization between Common Rule and FDA human subjects regulations, signaling ongoing alignment between these frameworks [16].

Practical Application: IRB Protocols and Procedures

IRB Composition and Function

The Institutional Review Board serves as the primary mechanism for implementing Belmont principles and regulatory requirements at the institutional level [21] [19]. Federal regulations mandate specific composition requirements to ensure comprehensive review capability:

- Minimum of five members with diverse backgrounds [19]

- Scientific and non-scientific representation, including at least one member with scientific and one with non-scientific background [19] [2]

- Community representation through at least one member not affiliated with the institution [19]

- Diversity in gender, race, cultural background, and sensitivity to community attitudes [19]

IRBs maintain written procedures for initial and continuing review, reporting of unanticipated problems, and ensuring prompt reporting of serious or continuing noncompliance [19] [20]. The IRB holds authority to approve, require modifications to, or disapprove research activities based on regulatory and ethical criteria [19].

Levels of IRB Review

Based on risk assessment and regulatory categories, IRBs conduct three levels of review:

- Exempt Review: For specific categories of minimal risk research involving no more than the level of risk encountered in everyday life [19] [15]. Exempt research requires initial IRB determination but not ongoing oversight.

- Expedited Review: For minimal risk research falling within nine specific categories defined by federal regulations [19]. A designated IRB reviewer rather than the full board conducts the review.

- Full Board Review: Required for research greater than minimal risk and studies involving vulnerable populations [19]. These studies require review by a fully convened IRB quorum and annual continuing review.

Table: IRB Review Categories and Criteria

| Review Level | Risk Level | Examples | Consent Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exempt | No more than minimal risk | Retrospective data analysis, educational tests | Often waived for secondary data |

| Expedited | Minimal risk | Prospective data collection, blood sampling | Required unless waiver granted |

| Full Board | Greater than minimal risk | Drug trials, invasive procedures, vulnerable populations | Comprehensive informed consent |

Documentation and Reporting Requirements

Effective implementation of Belmont principles requires robust documentation and reporting systems. Key requirements include:

- Unanticipated Problem Reporting: Investigators must promptly report all unanticipated problems involving risks to subjects or others [20]. These include any incident, experience, or outcome that is unexpected, related or possibly related to research participation, and suggests greater risk of harm than previously known [20].

- Protocol Deviations: Departures from the IRB-approved protocol must be reported, with major deviations (those impacting subject safety or risk-benefit ratio) reported promptly, and minor deviations summarized at continuing review [20].

- Informed Consent Documentation: IRBs must review and approve all informed consent documents to ensure they contain required elements in understandable language [19] [15].

- Continuing Review: Most research requires at least annual review by the IRB, though the revised Common Rule eliminated this requirement for certain minimal risk categories [16] [19].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Ethical Research Implementation

Table: Essential Materials for IRB Protocol Development and Ethical Review

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Implementation Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Belmont Report Framework | Ethical foundation for protocol design | Apply three principles systematically to all study aspects |

| Informed Consent Templates | Standardized consent documentation | Customize for specific population and risk profile |

| Vulnerability Assessment Tool | Identification of special population needs | Implement additional safeguards for vulnerable groups |

| Risk-Benefit Worksheet | Systematic evaluation of study risks/benefits | Document minimization strategies and benefit maximization |

| Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46) | Common Rule compliance reference | Apply to all federally funded human subjects research |

| FDA Regulations (21 CFR 50, 56) | Regulatory standards for clinical investigations | Required for drug, device, and product research |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Belmont Principles in IRB Submissions

Protocol Title: Systematic Integration of Ethical Principles in Human Subjects Research

Purpose: This protocol provides a standardized methodology for integrating Belmont Report principles into human research protocols, ensuring consistent application of ethical standards and regulatory compliance.

Background: The Belmont Report establishes three fundamental principles—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—that form the ethical foundation for human subjects protections in the United States [8] [2]. Federal regulations (Common Rule and FDA) operationalize these principles, but researchers must actively implement them in study design and conduct.

Materials Required:

- Research protocol document

- Informed consent templates

- Vulnerability assessment checklist

- Risk-benefit analysis worksheet

- Regulatory reference materials (45 CFR 46, 21 CFR 50/56)

Procedure:

Step 1: Respect for Persons Implementation

- Develop comprehensive informed consent process with all required elements [8] [17]

- Ensure consent information is presented in language understandable to prospective subjects

- Implement additional protections for persons with diminished autonomy (children, cognitive impairment, prisoners)

- Establish procedures for ongoing consent throughout research participation

Step 2: Beneficence Implementation

- Conduct systematic risk assessment identifying all potential harms (physical, psychological, social, economic)

- Design study to minimize risks through sound methodology and safety monitoring

- Maximize potential benefits through appropriate subject selection and research design

- Document favorable risk-benefit ratio with specific justification

Step 3: Justice Implementation

- Justify subject selection criteria based on scientific objectives, not convenience or vulnerability

- Ensure equitable distribution of research burdens and benefits across participant groups

- Implement additional safeguards for vulnerable populations routinely involved in research

- Assess and address potential for exploitation or undue influence

Step 4: IRB Integration and Documentation

- Submit complete research protocol including ethical integration documentation

- Respond to IRB requests for modification or clarification

- Implement approved protocol with fidelity to ethical commitments

- Report unanticipated problems or protocol deviations promptly

Timeline: The ethical integration process should begin during initial study design and continue through protocol development, IRB review, study implementation, and final reporting.

Quality Control: Implement ongoing monitoring of ethical compliance through regular protocol audits, consent process verification, and adverse event surveillance.

The bridge from the Belmont Report to contemporary regulations represents a dynamic system that continues to evolve with changing research paradigms. Recent developments, including the Revised Common Rule (2018) and emerging guidelines for pervasive data research (2024), demonstrate the ongoing adaptation of ethical principles to new research contexts [16] [22]. The single IRB mandate for multi-site studies and provisions for limited IRB review of certain exempt research reflect continuing efforts to streamline oversight while maintaining ethical rigor [19].

For researchers and IRB professionals, understanding this foundational relationship between ethical principles and regulatory requirements enables more effective protocol design and ethical review. By systematically applying the Belmont principles throughout the research lifecycle—from initial design through implementation and dissemination—the research community can maintain public trust and ensure the ethical conduct of human subjects research in increasingly complex scientific landscapes.

The Belmont Report, formally published in 1979, emerged from the work of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which was created by the National Research Act of 1974 [8] [23]. This foundational document was a direct response to grave ethical failures in research, most notably the Public Health Service (PHS) Tuskegee Study, where participants were deceived and denied effective treatment, and the Nuremberg Trials, which uncovered horrific human experimentation during World War II [23] [24]. The Report established three fundamental ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—to govern all research involving human subjects [8]. Rather than being a static historical document, the Belmont Report provides a durable analytical framework that continues to guide the ethical design, review, and conduct of modern scientific inquiry, ensuring that the well-being and rights of participants are paramount [10].

Core Ethical Principles and Their Regulatory Applications

The Belmont Report's three principles translate into specific regulatory requirements and practices within Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols. The table below summarizes these principles and their practical applications.

Table 1: The Three Ethical Principles of the Belmont Report and Their Applications

| Ethical Principle | Core Meaning | Application in Research & IRB Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Recognition of the autonomy of individuals and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy [8] [10]. | - Informed Consent Process: Providing ample information in an understandable manner, ensuring voluntary participation free from coercion, and offering the right to withdraw [8] [11]. |

| Beneficence | The obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize potential harms [8] [24]. | - Systematic Assessment of Risks and Benefits: A rigorous analysis to ensure that the risks to subjects are justified by the anticipated benefits [8] [1]. |

| Justice | The requirement to distribute the burdens and benefits of research fairly [10] [24]. | - Equitable Selection of Subjects: Ensuring that no racial, sexual, or economic group is systematically selected simply because of its easy availability, compromised position, or societal biases [8] [10]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these principles and their primary applications in research oversight.

Advanced Protocol Implementation: From Principle to Practice

Application Note: Implementing a Valid Informed Consent Process

Objective: To establish a consent process that truly embodies the principle of Respect for Persons, moving beyond a mere signed form to a dynamic, ongoing educational interaction.

Background: Informed consent is the practical application of Respect for Persons, ensuring individuals enter research voluntarily and with adequate information [8]. This is challenged in modern research involving complex biological therapies, big data, and genomic research, where risks may be uncertain or difficult to quantify.

Protocol Methodology:

Comprehension Assessment:

- Procedure: Develop a short, non-leading questionnaire or a "teach-back" method where the prospective subject explains the study's key elements in their own words.

- Documentation: Record the assessment method and outcome in the research record. The IRB should review and approve the tool.

- Rationale: Ensures the information was not only provided but also understood, which is crucial for populations with diminished autonomy or when dealing with highly technical concepts [8].

Documentation of Process:

- Procedure: Beyond the consent form signature, document the process itself. This includes the identity of the person obtaining consent, the date and location, the version of the consent form used, and a note on the overall interaction.

- Rationale: Creates an audit trail that demonstrates a meaningful process was followed, not just a form was signed.

Ongoing Consent for Longitudinal Studies:

- Procedure: For long-term studies, implement a process for re-consent. Triggers for re-consent may include the emergence of new significant risks or benefits, substantial protocol changes, or at pre-specified intervals (e.g., annually).

- Rationale: Respects the autonomous choice of the participant throughout the research relationship, acknowledging that their continued participation should be informed [11].

Application Note: Conducting a Systematic Risk-Benefit Analysis

Objective: To provide IRBs with a rigorous, evidence-based framework for justifying the risks of research by the potential benefits, fulfilling the principle of Beneficence.

Background: The principle of Beneficence requires that researchers and IRBs not only "do no harm" but also "maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms" [8]. This analysis is foundational to IRB approval.

Protocol Methodology:

Risk Identification and Categorization:

- Procedure: Create a comprehensive list of all foreseeable risks, categorizing them by:

- Type: Physical, psychological, social, economic, legal.

- Likelihood: Remote, unlikely, possible, probable, certain.

- Magnitude: Trivial, minor, serious, catastrophic.

- Duration: Transient, prolonged, permanent.

- Procedure: Create a comprehensive list of all foreseeable risks, categorizing them by:

Benefit Identification and Categorization:

- Procedure: List all anticipated benefits, clearly distinguishing:

- Direct benefit to the subject: Therapeutic studies only.

- Indirect benefit to the subject: e.g., access to healthcare, monetary compensation.

- Benefit to society: e.g., generation of new knowledge.

- Procedure: List all anticipated benefits, clearly distinguishing:

Systematic Assessment and Justification:

- Procedure: Weigh the categorized risks against the categorized benefits. The assessment must demonstrate that the risks are minimized and are reasonable in relation to the knowledge gained and/or the potential direct benefit to the subject.

- IRB Deliberation: The IRB must systematically consider alternatives to the proposed procedures and ensure the assessment is non-arbitrary and fact-based [8].

Table 2: Framework for Risk-Benefit Assessment in IRB Protocols

| Component | Assessment Criteria | Evidence for IRB Review |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Minimization | - Are all proposed procedures essential?- Are there safer alternative methods?- Are safety monitoring plans adequate? | - Protocol scientific rationale.- Literature on alternative methods.- Data safety monitoring plan (DSMP). |

| Benefit Maximization | - Is the research design sound and valid?- Will the study generate meaningful knowledge?- Are direct benefits to subjects realistic? | - Biostatistician review.- Preclinical and preliminary data.- Clinical equipoise statement. |

| Risk Justification | - Do the benefits to society/participants outweigh the risks?- Are the risks justified for the participant population? | - Summary of risks vs. benefits.- Justification for participant selection (link to Justice). |

Navigating Ethical Tensions: The Interplay of Principles

The principles of the Belmont Report are not always easily aligned and can come into conflict, requiring careful balancing by researchers and IRBs [11]. For example, in research involving children, the principle of Respect for Persons mandates honoring a child's dissent. However, if the research offers a direct therapeutic benefit (Beneficence) or is vital for generating knowledge for a condition that affects children as a class (Justice), the IRB may permit a parent's permission to override the child's dissent [11]. Another modern tension involves Justice in genomic research; to avoid creating "genetic orphans," efforts must be made to include diverse populations to ensure all groups can benefit from the advances, which itself requires a Respect for Persons through culturally competent consent processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Safeguards in Human Subjects Research

The following institutional and regulatory mechanisms serve as critical tools for implementing the ethical principles of the Belmont Report.

Table 3: Key Institutional Safeguards for Human Subjects Research

| Safeguard / Reagent | Primary Function | Role in Upholding Ethical Principles |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | An independent committee that reviews, approves, and monitors research involving human subjects [24]. | Serves as the primary operational mechanism for ensuring all three principles are applied to every research protocol before initiation and during conduct [8] [23]. |

| Informed Consent Form | The document used to provide key information to potential subjects and to document their voluntary agreement to participate. | The primary tool for fulfilling Respect for Persons, ensuring autonomous, informed, and voluntary participation [8] [11]. |

| Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) | An independent group of experts that monitors patient safety and treatment efficacy data while a clinical trial is ongoing [24]. | A critical component of Beneficence, actively working to protect subjects from harm by recommending trial modification or termination if risks outweigh benefits [24]. |

| Federalwide Assurance (FWA) | A formal commitment by an institution to the U.S. government that it will comply with federal regulations for the protection of human subjects [8]. | The binding agreement that holds an institution accountable for implementing a program guided by the Belmont Report's principles, thereby enforcing Justice and Beneficence at an organizational level [8]. |

| Protocol & Investigator's Brochure | The detailed plan for conducting the research and the compilation of clinical and non-clinical data on the investigational product. | Provides the essential information required for the IRB to perform a systematic Risk-Benefit Assessment (Beneficence) and ensure the scientific validity of the study. |

The workflow for ethical review and oversight, integrating these safeguards, is depicted below.

The Belmont Report has proven to be a remarkably resilient document. Its power lies not in providing specific answers to every ethical dilemma, but in offering a robust analytical framework—a "compass" rather than a checklist—for navigating the complex moral landscape of human subjects research [10]. As new frontiers in science emerge, from advanced gene therapies and artificial intelligence to novel public health crises, the core principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice provide a stable foundation for ethical deliberation. The ongoing relevance of the Belmont Report is a testament to its profound insight. By rigorously applying its principles through detailed protocols and institutional safeguards, the research community can maintain public trust, protect the rights and welfare of research participants, and responsibly pursue the scientific innovations that will benefit all of humanity.

Operationalizing Ethics: A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying Belmont Principles in Your Protocol

The Belmont Report, published in 1979, established Respect for Persons as one of three fundamental ethical principles for protecting human research subjects [25] [8]. This principle acknowledges the autonomy of individuals and requires that subjects with diminished autonomy are entitled to additional protections [8]. The practical application of Respect for Persons is realized through a robust informed consent process—a cornerstone of ethical research conduct that goes far beyond simply obtaining a signature on a document [26]. This protocol provides detailed guidance for researchers, IRB members, and drug development professionals on implementing a truly comprehensive informed consent process that embodies this foundational ethical principle. A well-constructed consent process ensures that participation is voluntary, informed, and ongoing, thereby safeguarding participant dignity and autonomy throughout the research lifecycle.

Core Principles and Regulatory Framework

The Belmont Report's Ethical Foundation

The Belmont Report emerged partly in response to ethical abuses in research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and continues to shape modern research ethics [25] [27]. Its principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two key ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents capable of making their own decisions, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to additional protection [8]. This dual obligation directly informs the requirements for informed consent, requiring researchers to ensure subjects enter research voluntarily with adequate information presented in comprehensible terms [8]. The Report makes specific recommendations about the information that should be conveyed to research subjects, including the research procedures, their purposes, risks and anticipated benefits, alternative procedures, and a statement offering subjects the opportunity to ask questions and withdraw at any time [8].

Regulatory Requirements and Guidelines

The ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report are codified in various federal regulations, primarily the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (the "Common Rule") found in 45 CFR part 46 [25] [17]. These regulations provide the legal framework for informed consent requirements, emphasizing that consent must be legally effective and procured only under circumstances that provide the prospective subject sufficient opportunity to consider whether to participate [26]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has additional informed consent regulations under 21 CFR Part 50 that apply to clinical investigations of drugs, medical devices, and biological products [17]. Recently, regulatory guidance has emphasized the need for a "concise and focused" presentation of key information at the beginning of the consent document to help potential participants understand why they might or might not want to participate in a research study [28] [29]. This reflects an evolving understanding of how to make consent processes more meaningful and effective.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Documents Governing Informed Consent

| Document/Guideline | Year Issued/Revised | Primary Focus | Jurisdiction/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Belmont Report | 1979 | Ethical Principles (Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice) | All NIH-funded human subjects research [8] |

| Nuremberg Code | 1947 | Voluntary consent essential for human experimentation | Foundation for modern consent standards [26] [17] |

| Declaration of Helsinki | 1964 (multiple revisions) | Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects | International biomedical research [17] |

| Common Rule (45 CFR 46) | 2018 (revised) | Basic HHS policy for protection of human research subjects | Federally funded research in the U.S. [25] [28] |

| FDA Regulations (21 CFR 50) | Ongoing | Informed consent requirements for clinical investigations | FDA-regulated clinical trials [29] [17] |

Essential Components of a Valid Informed Consent Process

A comprehensive informed consent process consists of several interdependent components, each requiring careful attention to ensure ethical and regulatory compliance.

Information Disclosure: Key Elements

Federal regulations mandate specific elements of information that must be provided to all prospective research subjects [28]. The 2018 Common Rule revision introduced the requirement that the consent document begin with a "concise and focused" presentation of key information that helps potential participants understand why they might or might not want to participate in the research [28] [29]. Recent guidance suggests this key information summary should include specific elements presented in a structured format.

Table 2: Essential Elements of Informed Consent

| Element Category | Specific Requirements | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Key Information Summary | Statement that project is research; purpose, duration, procedures; risks; benefits; alternatives [28] | Use headings, plain language (6th-8th grade level); present before detailed information [29] |

| Voluntary Participation | Statement that participation is voluntary; no penalty for refusal or withdrawal [26] | Explain process for withdrawal; emphasize no penalty at multiple points in process |

| Risk Disclosure | Reasonably foreseeable risks/discomforts [28] | Categorize by severity and frequency; include physical, psychological, social, economic risks |

| Benefit Description | Reasonably expected benefits to subjects or others [28] | Distinguish between direct and societal benefits; avoid overstating potential benefits |

| Confidentiality | How data will be stored, secured, accessed; who will have access [26] | Describe data protection measures; include certificate of confidentiality if applicable |

| Compensation | Details of any compensation; contact information for questions [26] | Clearly state compensation schedule; proration policy if participant withdraws early |

Comprehension and Voluntariness

Assessment of comprehension is a critical yet often overlooked component of the consent process [26]. Researchers must ensure prospective subjects truly understand the information being presented, which requires more than just providing a document to sign. Effective strategies include teach-back methods (asking participants to explain key concepts in their own words), using plain language at an appropriate reading level (generally 8th grade level or lower), and employing visual aids to explain complex procedures [28] [26]. The consent process must be free of any coercion or undue influence, with special protections for vulnerable populations who may be more susceptible to such pressures [8] [26]. This is particularly important for populations with diminished autonomy, such as children, prisoners, individuals with impaired decision-making capacity, or economically or educationally disadvantaged persons [8].

Documentation and Ongoing Consent

For most non-exempt research, informed consent must be documented with a written consent form signed by the participant or their legally authorized representative [28]. However, the consent process should be viewed as ongoing throughout the research study, not a single event that occurs at enrollment [26]. Researchers should conduct continued check-ins with participants to confirm consistent willingness to participate, provide opportunities for questions and concerns, and update consent when significant new information becomes available or when the study procedures change [26]. For research involving biological specimens, genetic analysis, or higher-risk interventions, additional consent elements and documentation are typically required [28].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Comprehensive Informed Consent Process

Pre-Consent Preparation Phase

Objective: To ensure all materials and processes are properly developed and reviewed before engaging with potential participants.

Materials and Reagents:

- IRB-approved protocol and consent documents

- Visual aids and supplementary materials for explaining complex concepts

- Accessibility resources (e.g., large print, translation services, screen-reader compatible digital formats)

Procedure:

- Protocol Finalization: Ensure the research protocol has received full IRB approval, including all consent-related materials [28].

- Consent Document Development:

- Use institutional templates that incorporate required regulatory elements and recommended language [28] [29].

- Write at an 8th-grade reading level or lower, using the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level formula to verify readability [28] [26].

- Begin with a key information section using the new structured format with specific headings [29]:

- "It is up to you whether you take part in the research"

- "Why are we doing the research, how long will it take, and what will be done?"

- "What are the most common or serious risks?"

- "What are the benefits?"

- "What can you do instead of being in the research?"

- "What if you are injured during the research?"

- "What are the costs or payments?"

- (Optional) "How participating in the research may affect your daily life" [29]

- Researcher Training: Train all study staff on the consent process, including how to explain study procedures, answer common questions, and assess understanding without coercion [26].

- Accessibility Compliance: Ensure all digital consent materials (including online platforms, surveys, and participant portals) conform to WCAG 2.1 AA standards for accessibility by April 2026, as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act [29].

Consent Execution Phase

Objective: To conduct the consent discussion and documentation in a manner that ensures genuine understanding and voluntary participation.

Materials and Reagents:

- IRB-approved consent documents

- Quiet, private space for discussion

- Materials for assessing understanding (e.g., open-ended questions)

Procedure:

- Initial Discussion:

- Comprehension Assessment:

- Verify the participant understands the purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives to participation.

- Confirm they understand their right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

- For complex studies, consider using a comprehension quiz to identify areas needing further explanation.

- Voluntariness Reinforcement:

- Explicitly state that participation is voluntary and refusal will not affect their relationship with the institution or access to standard care.

- Allow sufficient time for decision-making (at least 24 hours for higher-risk studies when feasible).

- Documentation:

- Obtain the participant's signature on the IRB-approved consent form after ensuring comprehension.

- Provide the participant with a copy of the signed document.

- For remote consent, use IRB-approved electronic consent processes with proper identity verification.

Post-Consent Maintenance Phase

Objective: To maintain ongoing communication with participants and ensure consent remains informed and voluntary throughout the study.

Materials and Reagents:

- Updated consent documents (if applicable)

- Communication tools for keeping in touch with participants

Procedure:

- Ongoing Check-ins: At each study visit or contact, briefly confirm the participant's continued willingness to participate and address any new questions or concerns [26].

- Consent Updates: If new information emerges that might affect a participant's willingness to continue (e.g., new risks identified in other study participants), obtain reaffirmed consent using an IRB-approved updated consent document.

- Process Evaluation: Periodically assess the consent process through participant feedback to identify areas for improvement.

- Documentation of Updates: Maintain careful documentation of any consent updates or reaffirmations in the research record.

The above diagram illustrates the comprehensive, multi-phase workflow for implementing a valid informed consent process that truly embodies the principle of Respect for Persons, from initial preparation through ongoing maintenance.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Consent Implementation

Table 3: Essential Resources for Effective Consent Processes

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| IRB-Approved Consent Templates | Provides regulatory-compliant structure with required language and elements [28] | Drafting study-specific consent documents; ensuring all required elements are included |

| Readability Assessment Tools (Flesch-Kincaid) | Measures reading level of consent documents; ensures appropriate comprehension level [26] | Verifying consent materials are at 8th grade level or lower; identifying complex passages |

| Accessibility Validation Tools (WAVE, aXe) | Checks digital compliance with WCAG 2.1 AA standards [29] | Ensuring online consent materials, surveys, and platforms are accessible to people with disabilities |

| Alternative Consent Formats (Video, PowerPoint) | Presents key information in multimedia formats to enhance understanding [29] | Supporting comprehension for low-literacy populations; explaining complex procedures visually |

| Comprehension Assessment Questions | Verifies participant understanding of key study elements [26] | Ensuring genuine informed consent; identifying areas needing further explanation |

| Digital Signature Platforms | Enables remote documentation of consent with identity verification | Obtaining valid consent for decentralized or remote clinical trials |

Discussion: Contemporary Challenges and Innovative Approaches

Implementing truly ethical informed consent processes faces several contemporary challenges. Approximately 20% of participants misunderstand risks, and 15% of studies lack resources for adequate diversity in recruitment [27]. The move toward digital and decentralized trials creates new challenges for ensuring authentic consent in virtual environments. Additionally, the increasing complexity of research, particularly in genetic studies and advanced therapeutics, makes comprehensible explanation of risks and benefits more difficult.

Innovative approaches are emerging to address these challenges. Some researchers are developing multimedia consent tools (videos, interactive modules) that can present key information more effectively than text-alone documents [29]. The FDA and OHRP have encouraged researchers to "develop innovative ways and utilize available technologies to provide key information" and to "consider developing alternate ways to present key information" [29]. Structured comprehension assessment tools are being integrated directly into consent processes to verify understanding before proceeding with enrollment. Furthermore, community engagement approaches are being used in the development of consent materials to ensure they are culturally appropriate and comprehensible to the target population.

A comprehensive informed consent process is the primary practical application of the Belmont Report's principle of Respect for Persons in human subjects research. By moving beyond a signature-focused approach to embrace a truly process-oriented model, researchers honor participant autonomy and build the foundation for ethical research conduct. This requires careful attention to information disclosure, comprehension assessment, and ongoing voluntariness throughout the research relationship. As research methodologies evolve, particularly with increasing digitalization and complexity, the informed consent process must similarly adapt while maintaining its fundamental ethical commitments. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a framework for implementing consent processes that truly respect persons as autonomous agents, thereby fulfilling both the ethical mandate of the Belmont Report and regulatory requirements governing human subjects research.

The principle of beneficence, as articulated in the Belmont Report, forms a cornerstone of ethical research involving human subjects. It encompasses a dual obligation: to maximize anticipated benefits while systematically minimizing potential risks [8]. For Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols, translating this ethical principle into practice requires a structured, transparent, and evidence-based risk-benefit analysis. This process ensures that the welfare of research participants is safeguarded and that the research design is sound and ethically justifiable. A well-executed analysis demonstrates respect for persons and justice by ensuring that the risks to which participants are exposed are warranted by the potential value of the knowledge gained. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing a rigorous risk-benefit assessment framework within IRB submissions, aligning with contemporary regulatory guidance and methodological standards.

Foundational Frameworks and Regulatory Context

The ethical mandate for risk-benefit analysis is embedded within international regulatory standards for human research protection and drug development.

The Belmont Report's Principles

The Belmont Report establishes three core principles. Respect for Persons requires acknowledging autonomy and protecting those with diminished autonomy, typically achieved through informed consent. Beneficence obligates researchers to not only protect participants from harm but also to secure their well-being by maximizing benefits and minimizing harms. Justice requires the fair distribution of both the burdens and benefits of research [8]. The IRB's application of these principles involves a deliberate and systematic review of the research plan to ensure these ethical convictions are upheld.

Contemporary Regulatory Guidance

Recent regulatory documents refine the application of beneficence in drug development. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) emphasizes that a benefit-risk assessment is a "case-specific, multi-disciplinary assessment of science and medicine" [30]. This assessment integrates diverse data sources, including clinical and non-clinical data, patient experience data, and real-world evidence, to form a comprehensive judgment [30]. Similarly, China's Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE) has released draft guidelines encouraging a structured approach, including the integration of multi-regional clinical trial (MRCT) data and real-world evidence (RWE) to strengthen assessments [31]. These guidelines highlight the importance of considering regional differences in disease characteristics and patient demographics, ensuring the analysis is contextually relevant.

Quantitative Data Analysis for Risk-Benefit Assessment

A rigorous analysis moves beyond qualitative description to a quantitative evaluation of potential outcomes. The following data types and analytical methods are critical for an evidence-based assessment.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Data Types for Risk-Benefit Analysis

| Data Category | Specific Data Points | Source in Research Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Benefit Data | Primary efficacy endpoint(s); Secondary efficacy endpoints; Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs); Quality of Life measures | Primary and secondary objectives; Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP); Outcome measures section |

| Risk Data | Incidence of Adverse Events (AEs); Incidence of Serious Adverse Events (SAEs); Laboratory abnormalities; Discontinuation rates due to AEs | Safety monitoring plan; Harms section; Stopping rules |

| Contextual Data | Natural history of disease/condition; Risks and benefits of standard of care or alternative interventions; Unmet medical need | Background and rationale; Choice of comparator |

Advanced Analytical Methods

To synthesize these data, researchers should employ robust quantitative data analysis methods [32]. The choice of method depends on the research question and data type.

- Descriptive Analysis: Serves as the starting point, summarizing what the data shows about benefits and risks (e.g., mean improvement in a symptom score, incidence rate of a specific adverse event).

- Diagnostic Analysis: Helps understand why certain outcomes occurred by examining relationships between variables (e.g., using regression analysis to identify patient subgroups that experience greater benefit or higher risk) [32].

- Predictive Analysis: Uses historical data and statistical modeling to forecast future trends and potential long-term outcomes, which is particularly valuable for chronic conditions [32].

The FDA guidance notes that data may be collected specifically to address benefit-risk questions or come from "routinely collected... real-world-data sources" [30]. Furthermore, sponsors should not wait for periodic reports to communicate "a potentially serious safety concern that could have an impact on a drug’s benefit-risk profile," underscoring the need for proactive, ongoing analysis [30].

Application Notes: A Protocol for IRB Submission

Integrating a rigorous risk-benefit analysis into an IRB protocol requires attention to both content and presentation. The following section provides a detailed, actionable protocol.

Protocol Development and Reporting Standards