Evaluating Quality Criteria for Empirical Ethics Research: Standards, Methods, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating quality criteria in empirical ethics research, addressing a critical gap in methodological standards.

Evaluating Quality Criteria for Empirical Ethics Research: Standards, Methods, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating quality criteria in empirical ethics research, addressing a critical gap in methodological standards. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational concepts of research ethics board composition and expertise, examines emerging methodological standards including rapid evaluation approaches, addresses common implementation challenges and optimization strategies, and discusses validation frameworks for assessing research quality. By synthesizing recent empirical evidence and international guidelines, this resource offers practical guidance for enhancing rigor, transparency, and ethical integrity in empirical ethics studies across biomedical and clinical research contexts.

Understanding Empirical Ethics Research: Core Principles and Current Landscape

Defining Empirical Ethics Research and Its Role in Evidence-Based Ethics

Empirical ethics research represents a significant methodological shift in bioethics, integrating socio-empirical research methods with normative ethical analysis to address concrete moral questions in medicine and science [1]. This approach has evolved from purely theoretical philosophical discourse to a multidisciplinary field that systematically investigates ethical issues using data collected from real-world contexts [2]. The emergence of what has been termed the "empirical turn" in bioethics over the past two decades reflects growing recognition that ethical decision-making must be informed by actual practices, experiences, and values of stakeholders rather than relying exclusively on abstract principles [3]. This comparative guide examines the fundamental characteristics of empirical ethics research, its relationship with evidence-based ethics, and the quality criteria essential for conducting rigorous studies in this evolving field.

Conceptual Definitions and Key Distinctions

What is Empirical Ethics Research?

Empirical ethics research utilizes methods from social sciences—such as anthropology, psychology, and sociology—to directly examine issues in bioethics [4]. This methodology investigates how moral values and ethical norms operate in real-world contexts, contrasting with purely theoretical ethics by grounding moral inquiry in observable human behavior and societal practices [5]. By employing techniques including surveys, interviews, ethnographic observations, and case studies, empirical ethics research provides data on actual moral decision-making processes, offering evidence about what people actually think, want, feel, and believe about ethical dilemmas [3].

What is Evidence-Based Ethics?

Modeled after evidence-based medicine, evidence-based ethics has been defined as "the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the conduct of research" [4]. A non-trivial interpretation of this concept distinguishes between "evidence" as high-quality empirical information that has survived critical appraisal versus lower-quality empirical information [6]. This approach demands that ethical decisions integrate individual expertise with the best available external evidence from systematic research, with particular attention to the quality and validity of the empirical information being utilized [6].

Comparative Relationship

The relationship between empirical ethics and evidence-based ethics represents a continuum of methodological rigor. While all evidence-based ethics incorporates empirical elements, not all empirical ethics research meets the stringent criteria to be considered "evidence-based." The key distinction lies in the systematic critical appraisal of evidence quality and the explicit process for integrating this evidence with ethical reasoning [6]. Empirical ethics provides the methodological toolkit for gathering data about ethical phenomena, while evidence-based ethics provides a framework for evaluating and applying that data in ethical decision-making [2] [6].

Quantitative Growth and Methodological Distribution

The evolution of empirical ethics research can be tracked quantitatively through its representation in leading bioethics journals. A comprehensive analysis of nine peer-reviewed journals in bioethics and medical ethics between 1990 and 2003 revealed significant trends in methodological approaches and publication patterns.

Table 1: Prevalence of Empirical Research in Bioethics Journals (1990-2003)

| Journal | Total Publications | Empirical Studies | Percentage Empirical |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing Ethics | 367 | 145 | 39.5% |

| Journal of Medical Ethics | 761 | 128 | 16.8% |

| Journal of Clinical Ethics | 604 | 93 | 15.4% |

| Bioethics | 332 | 22 | 6.6% |

| Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics | 332 | 18 | 5.4% |

| Hastings Center Report | 565 | 13 | 2.3% |

| Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics | 315 | 9 | 2.9% |

| Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal | 264 | 5 | 1.9% |

| Christian Bioethics | 194 | 2 | 1.0% |

| Overall | 4029 | 435 | 10.8% |

Table 2: Methodological Approaches in Empirical Bioethics Research (1990-2003)

| Research Paradigm | Number of Studies | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Methods | 281 | 64.6% |

| Qualitative Methods | 154 | 35.4% |

| Total | 435 | 100% |

The data reveal several important trends. First, the proportion of empirical research in bioethics journals increased steadily from 5.4% in 1990 to 15.4% in 2003 [7]. Second, the distribution of empirical research varies significantly across journals, with clinically-oriented publications (Nursing Ethics, Journal of Medical Ethics, and Journal of Clinical Ethics) containing the highest percentage of empirical studies [7]. Third, quantitative methodologies dominated the empirical landscape during this period, representing nearly two-thirds of all empirical studies [7].

Methodological Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

Research Designs in Empirical Ethics

Empirical ethics research employs diverse methodological approaches, each with distinct protocols for data collection and analysis:

Survey Research: Utilizes structured questionnaires to quantify attitudes, beliefs, and experiences of relevant stakeholders. For example, research on stored biological samples has employed survey methods to determine that most research participants prefer simple binary choices regarding future research use of their samples rather than detailed checklists of specific diseases [8]. Standard protocols include validated instruments, probability sampling where possible, and statistical analysis of responses.

Semi-structured Interviews: Collects rich qualitative data through guided conversations that allow participants to express nuanced perspectives in their own words. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring complex moral reasoning and contextual factors influencing ethical decisions [3]. Protocols typically include interview guides, audio recording, transcription, and thematic analysis using coding frameworks.

Ethnographic Observation: Involves extended engagement in natural settings to understand ethical practices as they occur in context. This method is especially useful for identifying discrepancies between formally stated ethical policies and actual behaviors [3]. Standard protocols include field notes, participant observation, and iterative analysis moving between data and theoretical frameworks.

Experimental Designs: Employ controlled conditions to test ethical interventions or measure their effectiveness. For instance, randomized controlled trials have been used to evaluate different approaches to improving research participants' understanding of informed consent documents [8]. Protocols follow standard experimental procedures with manipulation of independent variables and measurement of dependent variables.

Table 3: Methodological Framework for Empirical Ethics Research

| Research Category | Definition | Primary Methods | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | Assessing what "is" - current practices, beliefs, or attitudes | Surveys, interviews, observational studies | Documenting how ethics committees make decisions [4] |

| Comparative | Comparing the "is" to the "ought" | Normative analysis of empirical data | Identifying gaps between ethical guidelines and actual practices [4] |

| Intervention | Testing approaches to reconcile "is" and "ought" | Experimental trials, policy pilots | Evaluating ethics education programs [4] |

| Consensus | Analysis of multiple lines of evidence to establish norms | Delphi methods, systematic reviews | Developing guidelines for research ethics board composition [4] |

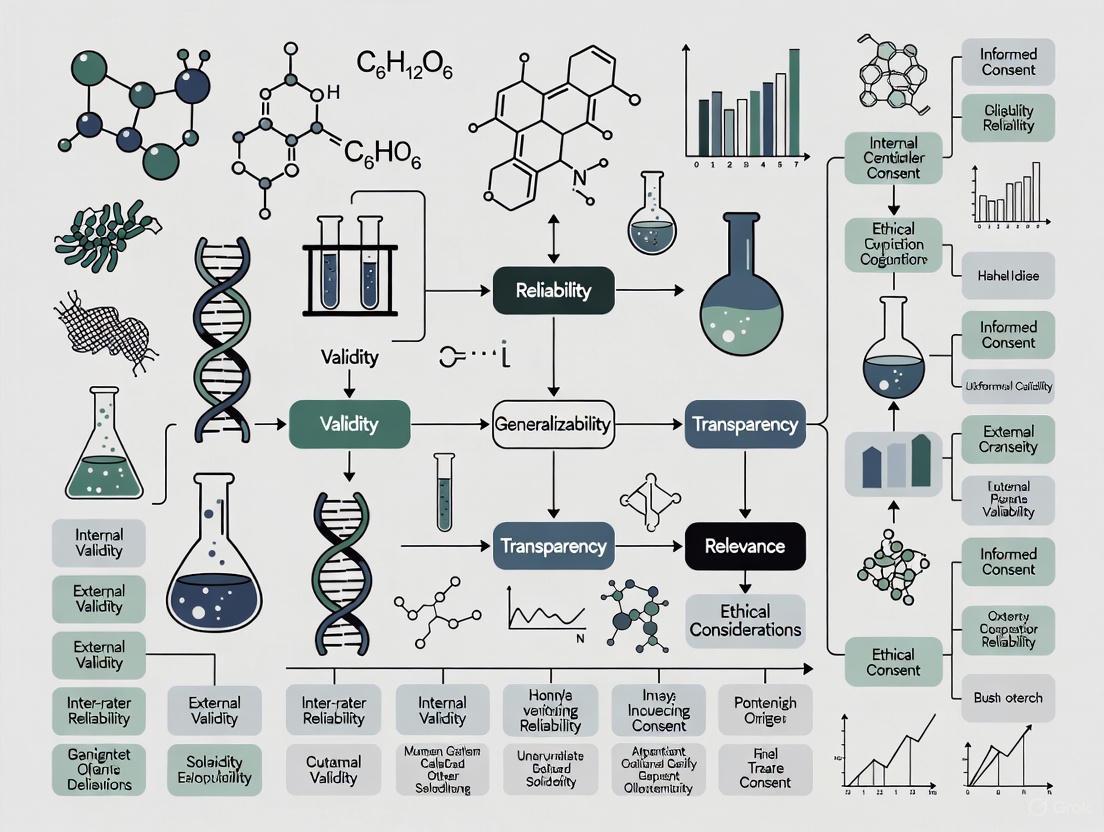

Conceptual Workflow for Empirical Ethics Research

The following diagram illustrates the integrated methodology that characterizes empirical ethics research, showing how normative and empirical approaches combine to produce ethically justified outcomes:

Quality Assessment Framework for Empirical Ethics Research

Evaluating the quality of empirical ethics research requires assessing both normative and empirical dimensions. The following criteria provide a framework for critical appraisal:

Normative Quality Criteria

Theoretical Adequacy: The ethical theory or framework selected must be adequate for addressing the specific issue at stake [1]. Different theoretical approaches (consequentialist, deontological, virtue ethics, etc.) may yield divergent normative evaluations, making the justification for theory selection essential [1].

Transparency: Researchers should explicitly state and justify their normative presuppositions and the ethical framework guiding the analysis [1]. This includes acknowledging values and biases that might influence research design or interpretation [6].

Reasoned Application: The process of applying normative frameworks to empirical findings should follow a systematic, well-reasoned approach rather than ad hoc justification [1]. This includes careful consideration of how empirical data informs, modifies, or challenges ethical principles.

Empirical Quality Criteria

Methodological Rigor: Research design, data collection, and analysis should meet established standards for empirical research in the relevant social scientific discipline [6]. This includes appropriate sampling strategies, valid measurement instruments, and proper analytical techniques.

Contextual Sensitivity: The research design should account for how contextual factors—organizational structures, cultural norms, power dynamics—influence ethical practices and perceptions [3]. This enhances the validity of findings by acknowledging the situated nature of ethical decision-making.

Reflexivity: Researchers should critically examine how their own positions, assumptions, and interactions might influence the research process and findings [3]. This includes considering how research questions are framed and whose perspectives are included or excluded.

Integrative Quality Criteria

Procedural Justification: The process of integrating empirical findings with normative analysis should be explicitly described and justified [1] [6]. Researchers should explain how facts inform values without committing naturalistic fallacies (deriving "ought" directly from "is").

Practical Applicability: The research should produce findings that can inform real-world ethical decisions, policies, or practices [3]. This includes consideration of implementability and potential consequences of applying the research findings.

Conducting rigorous empirical ethics research requires familiarity with diverse methodological approaches and tools. The following table outlines key resources and their applications:

Table 4: Essential Methodological Resources for Empirical Ethics Research

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Primary Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Approaches | Surveys, questionnaires, structured observations | Measuring prevalence of attitudes, testing hypotheses about ethical behaviors | Requires validated instruments, appropriate sampling strategies, statistical expertise |

| Qualitative Approaches | In-depth interviews, focus groups, ethnographic observation | Exploring moral reasoning, understanding ethical dilemmas in context | Demands researcher reflexivity, careful attention to power dynamics in data collection |

| Mixed Methods | Sequential or concurrent quantitative and qualitative data collection | Providing comprehensive understanding of complex ethical issues | Requires careful integration of different data types, may involve larger research teams |

| Systematic Review Methods | Meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, scoping reviews | Synthesizing existing empirical research on specific ethical questions | Essential for evidence-based ethics; must address quality appraisal of included studies [9] |

Comparative Analysis: Evidence-Based Ethics in Practice

The application of evidence-based approaches to ethics presents both opportunities and challenges. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual structure and procedural flow of evidence-based ethics:

Practical Applications and Limitations

Evidence-based ethics finds application across multiple domains:

Research Ethics Committees: Empirical research on REB composition and functioning informs evidence-based approaches to improving ethical review processes [9]. Studies have examined how different forms of expertise (scientific, ethical, legal, community perspectives) influence review quality and outcomes [9].

Clinical Ethics Consultation: Evidence-based approaches can improve the quality and consistency of ethics consultation services by systematically evaluating consultation outcomes and methods [8].

Policy Development: Evidence-based ethics supports the development of ethically sound policies by integrating empirical data about stakeholder values, preferences, and experiences with normative analysis [3].

However, evidence-based ethics faces significant limitations. The approach risks privileging quantifiable data over important qualitative ethical considerations and may implicitly favor certain values through its methodological choices [2] [6]. There remains ongoing debate about appropriate quality criteria for empirical research in ethics and how to differentiate between high and low-quality information [6].

Empirical ethics research represents an essential methodology for addressing complex ethical challenges in healthcare, research, and emerging technologies. By systematically integrating robust empirical data with thoughtful normative analysis, this approach grounds ethical reflection in the actual experiences, values, and practices of relevant stakeholders. The evidence-based ethics movement further strengthens this approach by emphasizing critical appraisal of empirical evidence and transparent procedures for integrating evidence with ethical decision-making.

As the field continues to develop, researchers should prioritize methodological rigor, theoretical transparency, and practical applicability. Quality empirical ethics research must meet standards for both empirical social science and normative ethics while developing integrative frameworks that respect the distinctive contributions of each approach. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding these methodologies enables critical appraisal of empirical ethics literature and contributes to more ethically informed practices and policies.

Essential Components of Effective Research Ethics Boards (REBs)

Research Ethics Boards (REBs), also known as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Research Ethics Committees (RECs), serve as independent committees tasked with reviewing, approving, and monitoring biomedical and behavioral research involving human participants [10] [11]. Their fundamental mission is to protect the rights, safety, and welfare of individuals who volunteer to take part in research studies [11] [12]. This protective role emerged from a history of research misconduct and abuse, leading to the development of national and international regulations [13] [12]. Effective REBs operate as more than just bureaucratic hurdles; they are vital partners in the research enterprise, ensuring that the search for scientific knowledge does not come at the cost of human dignity or well-being. By upholding rigorous ethical standards, they foster public trust in scientific research and ensure that the benefits of research are realized responsibly [11].

This guide evaluates the essential components that contribute to an REB's effectiveness, framed within a broader thesis on quality criteria for empirical ethics research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these components is crucial for navigating the ethics review process successfully and for appreciating the structural and operational elements that underpin robust ethical oversight.

Foundational Ethical Principles and History

The operation of all REBs is guided by a set of core ethical principles, primarily derived from key historical documents that emerged in response to ethical breaches in research.

Historical Context and Governing Principles

The need for ethical oversight became glaringly apparent after the atrocities of World War II, leading to the Nuremberg Code in 1947, which established the absolute necessity of voluntary consent [12]. This was followed by the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964, which further solidified guidelines for clinical research [12] [14]. In the United States, the public exposure of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study prompted the National Research Act of 1974, which formally created IRBs [10] [12]. The subsequent Belmont Report articulated three fundamental principles that continue to provide the ethical framework for human subjects research [12] [14]:

- Respect for Persons: Recognizing the autonomy of individuals and protecting those with diminished autonomy, often operationalized through the informed consent process [11] [12].

- Beneficence: The obligation to maximize benefits and minimize possible harms to research participants [11] [12].

- Justice: Ensuring the fair distribution of the benefits and burdens of research, so that no particular group is unfairly burdened or excluded [11] [12].

In Canada, the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS2) is the prevailing national standard, providing a comprehensive framework for the ethical conduct of research involving humans [13] [15] [14].

Table 1: Historical Foundations of Research Ethics

| Document/Event | Year | Key Contribution | Impact on REB Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuremberg Code | 1947 | Established the requirement for voluntary informed consent | Foundation for modern consent standards and the right to withdraw without penalty [12]. |

| Declaration of Helsinki | 1964 | Stressed physician-investigators' responsibilities to their patients | Emphasized the well-being of the subject over the interests of science and society [12]. |

| Tuskegee Syphilis Study | Revealed 1972 | Long-term study withholding treatment from Black men with syphilis | Catalyzed the National Research Act and formal creation of IRBs in the U.S. [12]. |

| The Belmont Report | 1979 | Articulated three core principles: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice | Provides the primary ethical framework for REB review and federal regulations [12] [14]. |

| Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS2) | Current | Canadian policy for ethical conduct of research involving humans | Mandatory standard for all research funded by Canada's three federal research agencies [13] [14]. |

Core Structural Components of an Effective REB

The effectiveness of an REB is contingent upon its foundational structure, which ensures its independence, competence, and capacity to conduct thorough reviews.

Diverse and Qualified Membership

A multidisciplinary composition is critical for a competent and comprehensive review of research proposals. Regulations typically mandate a minimum of five members [12], but effective boards often include a diverse group with varied expertise and perspectives [15] [11]. The membership should include:

- Scientific Members: Individuals with expertise in the specific research disciplines and methodologies commonly reviewed (e.g., medicine, psychology, social sciences) [15] [12].

- Non-Scientific Members: Members from diverse backgrounds, including law, ethics, and community representatives, to provide non-specialist perspectives [15] [10] [12].

- Legal and Ethical Expertise: At least one member knowledgeable in law and one in ethics to guide complex legal and ethical considerations [15].

- Community Representation: Members recruited from the general population and specific communities (e.g., Indigenous communities) to safeguard community values and participant interests [15]. This diversity helps ensure that the REB can adequately assess the scientific validity, potential risks and benefits, and community acceptability of the research [11].

Operational Independence and Institutional Support

For an REB to function effectively, it must be independent from undue influence. The REB must have the authority to approve, require modifications in, or disapprove research, and its decisions should be free from coercion or interference from institutional or sponsor interests [10] [16]. As noted by Health Canada, institutions are required to provide "necessary and sufficient ongoing financial and administrative resources" to support the REB's functioning [13]. This includes:

- Adequate Administrative Support: Sufficient staff to manage the workflow, from application intake to communication with researchers [13].

- Protected Time for Members: REB membership requires a significant time commitment for reviewing materials and attending meetings, which must be recognized and supported by the institution [15].

- Clear Reporting Lines: While administratively supported by the institution, the REB should report to a high level (e.g., to a deputy minister or president) to preserve its independent voice [15].

Operational and Procedural Components

Beyond its structure, the REB's day-to-day processes are fundamental to its efficiency and effectiveness.

Systematic Review Workflow

The ethics review process is often perceived as a "black box," but effective REBs operate through a well-defined, multi-stakeholder workflow [13]. Inefficiencies often arise from applications stalling or moving backward in the process due to incomplete submissions or poor communication.

Diagram 1: REB Review Workflow and Stakeholders

This workflow illustrates the critical roles and potential backflows that cause delays. The model shows that researchers, administrators, and REB members all share accountability for the timely movement of an application [13].

Comprehensive Documentation and Review Criteria

The review process is anchored in a set of essential documents that form the backbone of any clinical trial or research study [17]. These documents ensure compliance, protect participants, and provide an audit trail [17]. The core documents required for review typically include:

- Research Protocol: The comprehensive blueprint for the study, detailing objectives, design, methodology, and statistical considerations [17].

- Informed Consent Form (ICF): The document ensuring participants are provided all necessary information in plain language to make a voluntary decision [17].

- Investigator's Brochure (IB): A compilation of all clinical and non-clinical data on the investigational product [17].

- Case Report Form (CRF): The tool for standardized data collection from each participant [17].

- Clinical Study Report (CSR): The comprehensive summary of the entire clinical trial upon completion [17].

The REB then evaluates these documents against a set of rigorous criteria [14]:

- Scientific Soundness & Methodology: The research must be scientifically valid and justified [14].

- Risk-Benefit Analysis: Potential benefits must significantly outweigh potential harms [14].

- Informed Consent Process: The process for obtaining voluntary, informed consent must be adequate [14].

- Privacy & Confidentiality: Robust measures must be in place to protect participant data [14].

- Selection & Recruitment: The selection of participants must be fair and just [14].

Performance Metrics and Global Comparison

A key challenge for REBs is balancing thoroughness with efficiency. Lengthy review times are a consistent complaint within the research community and can have serious consequences, including the loss of research resources and delays in patient access to new therapies [13].

Quantitative Review Timelines Across Countries

A global comparison of ethical review protocols reveals significant heterogeneity in review timelines, which can impact international research collaboration [18]. The table below summarizes the typical approval timelines for different study types across a selection of countries.

Table 2: International Comparison of Ethical Approval Timelines

| Country / Region | Audit / Routine Review | Observational Study | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Key Regulatory Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | Local audit registration | 1-3 months [18] | >6 months [18] | Decision-making tool to classify studies; arduous process for interventional studies [18]. |

| Belgium | >3-6 months [18] | >3-6 months [18] | 1-3 months [18] | Lengthy process for audits/observational studies; written consent mandatory for all research [18]. |

| India & Ethiopia | >3-6 months [18] | >3-6 months [18] | 1-3 months [18] | Protracted review for lower-risk studies; local or national-level review [18]. |

| Hong Kong & Vietnam | Audit registration / Waiver review [18] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Shorter lead times for audits; initial review to assess need for formal process [18]. |

| General Timeline | Varies widely | 1-3 months [18] | 1-6+ months [18] | Centralized review for multisite trials enhances efficiency [13] [18]. |

Strategies for Improving Efficiency

To address delays, stakeholders can adopt targeted best practices [13]:

- Researchers: Develop scientifically sound proposals and ensure applications are thorough and complete from the outset. Understand and apply research ethics standards before submission [13].

- REB Members: Understand and consistently apply ethics standards, respect review timelines, and participate in ongoing education [13].

- Institutions: Provide necessary administrative support responsive to workload variations and promote a culture of respect for the ethics review process [13].

- Systemic Improvements: Moving toward regionalized or centralized ethics review for multi-site research can dramatically improve efficiency by eliminating redundant reviews at each center [13] [18].

For researchers preparing an ethics application, understanding the required materials and their function is crucial. The following table details the "research reagent solutions" – the essential documents and resources needed for a successful REB submission.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for REB Submission

| Item / Document | Category | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Protocol | Pre-trial Document | Serves as the study's blueprint, detailing objectives, design, methodology, and statistical plan [17]. | Must be scientifically rigorous and feasible; basis for regulatory oversight [17]. |

| Informed Consent Form (ICF) | Pre-/During-trial Document | Ensures participant autonomy by providing all necessary information in plain language for a voluntary decision [17]. | Requires REB approval; must outline risks, benefits, confidentiality, and right to withdraw [17]. |

| Investigator's Brochure (IB) | Pre-trial Document | Compiles all relevant clinical/non-clinical data on the investigational product for investigator safety assessment [17]. | Must be regularly updated as new safety information emerges [17]. |

| Case Report Form (CRF) | During-trial Document | Standardized tool (paper/electronic) for collecting data from each participant to ensure consistency [17]. | Design should align with the protocol and minimize data entry errors [17]. |

| Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS 2) | Guidance Document | The prevailing Canadian standard for ethical research; guides REB evaluation criteria [15] [14]. | Researchers should be familiar with its principles before designing studies and submitting applications [13]. |

| REB Application Checklist | Administrative Document | Institutional-specific list to ensure all components of the application are complete upon submission [13]. | Consulting this and the REB in advance of submission prevents delays [13]. |

Effective Research Ethics Boards are not defined by a single component but by a synergistic integration of multiple elements. They are built upon a foundation of core ethical principles, operationalized through a diverse and independent structure, and maintained via systematic and transparent procedures. The efficiency of their operation, measured through metrics like review timelines, is as critical as their adherence to ethical rigor. As the landscape of research becomes increasingly global and complex, the continued evolution and standardization of REB processes—while preserving their fundamental protective role—will be essential. For the research community, engaging with the REB as a partner from the earliest stages of study design, armed with a clear understanding of these essential components, is the most effective strategy for ensuring that valuable research can proceed ethically and without unnecessary delay.

Empirical ethics research (EER) represents an important and innovative development in bioethics, directly integrating socio-empirical research with normative-ethical analysis to produce knowledge that would not be possible using either approach alone [19]. This interdisciplinary field uses methodologies from descriptive disciplines like sociology, anthropology, and psychology—including surveys, interviews, and observation—but maintains a strong normative objective aimed at developing ethical analyses, evaluations, or recommendations [19]. The fundamental challenge, and the core thesis of this evaluation, is that poor methodology in EER does not merely render a study scientifically unsatisfactory; it risks generating misleading ethical analyses that deprive the work of scientific and social value and can lead to substantive ethical misjudgments [19]. Therefore, establishing robust quality criteria is not merely an academic exercise but an ethical necessity in itself. This guide evaluates these criteria across three critical domains: scientific rigor, ethical integrity, and participant perspective, providing a framework for researchers to assess and improve their empirical ethics work.

Domain Comparison: Scientific, Ethical, and Participant Perspectives

The quality of EER depends on meeting interdependent criteria across three foundational domains. The table below synthesizes these core components, their quality benchmarks, and the consequences of their neglect.

| Domain | Core Components | Key Quality Criteria | Consequences of Poor Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Perspective [19] [20] [21] | - Primary Research Question- Theoretical Framework- Methodology & Data Analysis | - Clarity and focus of the primary research question.- Appropriate and justified methodological choice (qualitative/quantitative).- Rigorous experimental design (e.g., randomization, control groups, blinding) to establish causation.- Accurate and transparent data presentation. | - Inability to establish cause-and-effect (causation).- Results confounded by lurking variables.- Misleading findings and wasted resources.- Undermines scientific validity and ethical analysis. |

| Ethical Perspective [19] [20] [21] | - Research Ethics & Scientific Ethos- Interdisciplinary Integration- Normative Reflection | - Approval by an Institutional Review Board (IRB).- Informed consent from participants.- Data privacy and confidentiality.- Minimization of risks.- Explicit integration of empirical findings with normative argumentation. | - Direct harm or exploitation of research subjects.- Violation of legal and professional standards.- "Crypto-normative" conclusions where evaluations are implicit and unexamined.- Study fails to achieve its normative purpose. |

| Participant Perspective [19] [20] [21] | - Participant Safety & Autonomy- Mitigation of Bias- Transparency | - Participant well-being is prioritized over research goals.- Use of placebos and blinding to counter power of suggestion (e.g., placebo effect).- Procedures are clearly explained, and participation is voluntary. | - Physical or psychological harm to participants.- Coercion and erosion of trust in research.- Biased results due to participant or researcher expectations (e.g., in non-blinded studies). |

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Causation

A core requirement from the scientific perspective is the ability to design experiments that can reliably test hypotheses and support causal inferences. The following protocols are fundamental.

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

The RCT is the gold standard experimental design for isolating the effect of a treatment and establishing cause-and-effect relationships [20] [21].

Detailed Methodology:

- Definition of Variables: Identify the explanatory variable (the treatment or intervention being tested) and the response variable (the outcome being measured) [21].

- Recruitment and Random Assignment: Recruit a sample of participants from the target population. Randomly assign these participants to either a treatment group (which receives the active intervention) or a control group (which receives a placebo or standard treatment) [20]. Randomization ensures that all potential lurking variables are spread equally among the groups, making the treatment the only systematic difference [21].

- Blinding: Implement a double-blind procedure where neither the participants nor the researchers interacting with them know which group is receiving the active treatment. This prevents biases in reporting and interpretation due to the power of suggestion or expectation [21].

- Execution and Data Collection: Administer the treatments for a predefined period under controlled conditions. Measure the resulting changes in the response variable for all participants [20].

- Analysis: Compare the outcomes of the treatment and control groups using appropriate statistical tests. A statistically significant difference in the response variable can be attributed to the explanatory variable due to the random assignment [21].

Example: Investigating Aspirin and Heart Attacks

- Population: Men aged 50 to 84 [21].

- Sample & Experimental Units: 400 men recruited for the study [21].

- Explanatory Variable: Oral medication (aspirin vs. placebo) [21].

- Treatments: Aspirin and a placebo [21].

- Response Variable: Whether a subject had a heart attack [21].

Observational Study and Its Limitations

In contrast to experiments, observational studies are based on observations or measurements without manipulating the explanatory variable [21].

Detailed Methodology:

- Identification of Cohort: Identify a group of subjects to be studied.

- Measurement: Record data on variables of interest for these subjects. This can be done prospectively (following subjects forward in time) or retrospectively (using historical data).

- Analysis: Look for apparent associations or correlations between the explanatory and response variables.

Key Limitation: An observational study can only identify an association between two variables; it cannot prove causation [20] [21]. This is because of potential confounding (lurking) variables—other unmeasured factors that could be the true cause of the observed effect [21].

Example: Vitamin E and Health An observational study might find that people who take vitamin E are healthier. However, this does not prove vitamin E is the cause. The improved health could be due to lurking variables, such as the fact that vitamin E users may also exercise more, eat a better diet, or avoid smoking [21].

Visualizing Workflows in Empirical Ethics Research

Effective data visualization is crucial for communicating complex research designs and findings. The following diagrams, created with DOT language and adhering to specified color and contrast rules, illustrate key workflows.

Empirical Ethics Research Workflow

Experimental vs. Observational Study Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of EER requires both conceptual and practical tools. The following table details key "reagents" and their functions in the research process.

| Item / Solution | Function in Empirical Ethics Research |

|---|---|

| Theoretical Framework [19] | Provides the underlying philosophical and social science concepts that guide the research question, methodology, and interpretation of findings. |

| Validated Data Collection Instruments [19] | Ensures the reliability and validity of collected data. Includes pre-tested survey questionnaires, structured interview guides, and standardized observation protocols. |

| Interdisciplinary Research Team [19] | A collaborative group with expertise in both normative ethics and empirical social science methods. Crucial for overcoming methodological biases and achieving genuine integration. |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocol [20] [21] | A formal research plan submitted for approval to an ethics board. It details how the study will minimize risks, obtain informed consent, and protect participant privacy. |

| Blinding Materials (Placebos) [20] [21] | Inactive substances or fake treatments that are indistinguishable from the real intervention. They are essential for controlling for the placebo effect in experimental designs. |

| Data Visualization Software [22] [23] | Tools (e.g., Tableau, R/ggplot2, Datawrapper) used to create effective charts and graphs that accurately and clearly communicate data patterns and relationships. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software | Software (e.g., NVivo, MAXQDA) that aids in the systematic coding, analysis, and interpretation of non-numerical data from interviews, focus groups, or documents. |

| Informed Consent Documents [20] [21] | Legally and ethically required forms that clearly explain the study's purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits to participants, ensuring their voluntary agreement is based on understanding. |

Data Visualization Principles for Accessible Communication

Presenting data effectively is a key component of scientific rigor. Adhering to established principles ensures that visuals are accurate, informative, and accessible to all readers, including those with color vision deficiencies [24].

- Diagram First: Prioritize the information and message before engaging with software. Focus on the core story (e.g., a comparison, trend, or distribution) rather than defaulting to a specific chart type [22].

- Use an Effective Geometry: Select the chart type that best represents your data. Avoid misuse of geometries; for example, bar plots are for amounts and counts, but should not be used to show group means with distributional information [22]. Use scatterplots for relationships, box plots or violin plots for distributions, and line charts for trends over time [22] [25].

- Use Color Strategically: Color should enhance readability, not overwhelm. Use it to highlight key data points or to distinguish categories [25] [23]. Ensure sufficient color contrast; for normal text, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) AA standard requires a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 [26] [27].

- Keep it Simple (Avoid Chartjunk): Eliminate unnecessary elements like excessive gridlines, decorations, or 3D effects that distract from the data. Maximize the data-ink ratio, which is the amount of ink used for data versus the total ink in the figure [22] [25].

- Provide Context with Labels: Always include clear titles, axis labels, and legends where necessary. This ensures viewers can understand what the data represents without confusion [23].

Current Gaps in Empirical Research on Ethics Review Quality

The quality of ethics review is a cornerstone of ethical research involving human subjects. Research Ethics Boards (REBs), also known as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Ethics Review Committees (ERCs), carry the critical responsibility of protecting participant rights and welfare. While international guidelines outline membership composition and procedural standards, a significant disconnect exists between these normative frameworks and the empirical evidence supporting specific configurations for optimal performance. This analysis identifies and systematizes the current empirical research gaps concerning ethics review quality, providing researchers with a roadmap for future investigative priorities.

Major Identified Research Gaps

A 2025 scoping review of empirical research on REB membership and expertise highlights a "small and disparate body of literature" and explicitly concludes that "little evidence exists as to what composition of membership expertise and training creates the conditions for a board to be most effective" [9]. The table below summarizes the core empirical gaps clustered into four central themes.

Table 1: Core Empirical Gaps in Ethics Review Research

| Thematic Area | Specific Empirical Gap | Key Question Lacking Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| REB Membership & Expertise | Optimal composition of scientific expertise [9] | What specific mix of scientific expertise enables most effective review of diverse protocols? |

| Effectiveness of ethical, legal, and regulatory training [9] | Which training modalities most improve review quality and decision-making? | |

| Impact of identity and perspective diversity [9] | How does demographic/professional diversity concretely affect review outcomes and participant protection? | |

| Informing Policy & Guidelines | Evidence-based updates to ethics guidelines [28] | How can empirical data on gaps directly inform and improve official ethics guidelines? |

| Guidance for novel trial designs (e.g., Stepped-Wedge CRTs) [28] | What specific ethical frameworks are needed for complex modern trial designs? | |

| Oversight of Evolving Methodologies | Purview over big data and AI research [29] | How can REBs effectively oversee research with novel risks (privacy, algorithmic discrimination)? |

| Functional capacity for data-intensive review [29] | Do REBs possess necessary technical expertise and procedures for big data/AI protocol review? | |

| System Efficiency & International Collaboration | Quality and efficiency metrics for review models [30] | What metrics best measure the quality and efficiency of ethics review systems? |

| Practical implementation of mutual recognition models [30] | How can reciprocity, delegation, and federation models be operationalized effectively across borders? |

Unexplored Dimensions of REB Membership and Training

The composition and training of REBs represent a foundational gap. Despite clear guidelines recommending multidisciplinary membership, the empirical evidence demonstrating which specific combinations of expertise lead to more effective human subject protection is notably absent [9]. Furthermore, while some training is standard, research has not established which formats—online modules, workshops, or other methods—most significantly improve committee members' review capabilities [9]. The inclusion of community members is intended to represent participant perspectives, but empirical studies have not robustly measured the causal impact of this diversity on the ethical quality of review decisions [9].

The Challenge of Novel Research Methodologies

The rapid evolution of research methodologies has created a significant lag in ethical oversight. The emergence of big data research exposes "purview weaknesses," where studies can evade review entirely, and "functional weaknesses," where REBs lack the specialized expertise to evaluate risks like privacy breaches and algorithmic discrimination [29]. Similarly, in clinical trial design, the adoption of cluster randomized trials (CRTs) and stepped-wedge designs has outpaced the development of specific ethics guidance. A 2025 citation analysis identified 24 distinct gaps in the seminal Ottawa Statement guidelines for CRTs, highlighting a pressing need for evidence-based guidance updates [28].

System-Level Inefficiencies and the Need for New Metrics

At a systemic level, the prevailing model of replicated, local ethics review for multi-site and international research is often inefficient without clear evidence of improved participant protection [30]. While alternative models like reciprocity, delegation, and federation have been proposed, empirical research is needed to define the metrics for evaluating their quality and efficiency [30]. Without this evidence, the implementation of these streamlined models remains challenging.

Experimental Protocols for Gap Investigation

To address these gaps, researchers can employ several empirical methodologies. The following diagram outlines a sequential mixed-methods approach to investigate a specific research gap, combining qualitative and quantitative data for a comprehensive analysis.

Figure 1: A sequential mixed-methods protocol for investigating ethics review gaps.

Detailed Methodology:

- Scoping and Systematic Reviews: As demonstrated in the 2025 review on REB membership, this method is essential for mapping the existing literature and precisely identifying where evidence is lacking. The process involves identifying research questions, selecting relevant studies, and systematically charting the data to summarize findings [9].

- Qualitative Inquiry: Semi-structured interviews and focus groups with key stakeholders—including REB chairs, members, researchers, and research participants—are critical. This approach explores complex phenomena, such as how REBs deliberate on big data risks or how community members perceive their role, providing rich, contextual insights that surveys alone cannot capture [9].

- Quantitative Surveys: Following qualitative analysis, surveys can test hypotheses and measure the prevalence of certain views or practices across a larger population. For example, a survey could quantify the percentage of REBs that have specific training modules on AI ethics or measure the correlation between certain membership characteristics and perceived review quality [31].

- Citation and Document Analysis: This method involves systematically analyzing publications, guidelines, and policy documents. The 2025 gap analysis of the Ottawa Statement used this to great effect, reviewing 53 articles that cited the guideline to identify 24 specific areas where guidance was missing or inadequate [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Methodological Tools for Empirical Ethics Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Investigation |

|---|---|

| Systematic Review Protocol | Provides a structured, replicable plan for comprehensively identifying, selecting, and synthesizing all relevant literature on a specific ethics topic [9]. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Guide | Ensures consistent coverage of key topics (e.g., training experiences, challenges with big data) while allowing flexibility to explore novel participant responses [9]. |

| Stakeholder-Specific Survey Instrument | Quantifies attitudes, experiences, and practices across a large sample of a target group (e.g., REB members, researchers) to generate generalizable data [31]. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo) | Aids in the efficient organization, coding, and thematic analysis of large volumes of textual data from interviews or documents [28]. |

| Citation Tracking & Analysis Matrix | Enables systematic identification and review of publications that have engaged with a key guideline or paper to catalog critiques and identified gaps [28]. |

| Data Anonymization Framework | Protects participant confidentiality by providing a secure protocol for removing or encrypting identifiable information from collected data, which is crucial when studying ethics professionals [32]. |

The empirical foundation for ensuring high-quality ethics review is characterized by significant, evidence-based gaps. Critical questions about the optimal composition and training of REBs, effective oversight of big data and AI research, and the implementation of efficient international review models remain largely unanswered. Addressing these gaps requires a concerted effort from the research community, employing rigorous mixed-methods approaches, including scoping reviews, qualitative studies, and quantitative surveys. Filling these empirical voids is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for building a more robust, effective, and trustworthy system for protecting human research participants in an evolving scientific landscape.

International Guidelines and Regulatory Frameworks (CIOMS, Common Rule)

The global landscape of health-related research is governed by a complex framework of ethical guidelines and regulatory requirements designed to protect human participants. Two of the most influential frameworks are the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans developed by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and the Common Rule (45 CFR Part 46) codified in United States regulations. While both share the fundamental goal of ethical research conduct, they differ significantly in their origin, scope, structure, and application. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these frameworks, focusing on their practical implications for research ethics boards (REBs), also known as institutional review boards (IRBs), and researchers operating in an international context. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for designing and implementing quality empirical ethics research that meets international standards [9] [33].

Framework Origins and Philosophical Underpinnings

The CIOMS guidelines and the U.S. Common Rule emerged from distinct historical contexts and philosophical traditions, shaping their fundamental approaches to research ethics.

CIOMS Guidelines: Developed collaboratively through the World Health Organization and UNESCO, CIOMS provides internationally applicable guidelines that are aspirational and principle-based. They are designed to be adapted across diverse cultural, economic, and legal environments, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The guidelines build upon the Declaration of Helsinki and emphasize global health justice and contextual application. A key philosophical commitment is their focus on vulnerability and the need for community engagement, reflecting a global perspective on research ethics that seeks to be relevant beyond well-resourced settings [9] [33].

The Common Rule: As a U.S. federal regulation, the Common Rule is a legally binding, prescriptive framework primarily governing federally funded or supported research within the United States. It operationalizes the ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—into specific regulatory requirements. Its philosophical basis is rooted in a rights-based approach within a specific regulatory culture, emphasizing procedural compliance and standardized protections across all institutions subject to its authority. The Common Rule's revisions aim to reduce administrative burden while maintaining rigorous participant protections, reflecting a focus on regulatory efficiency within a specific national context [33] [34].

Table 1: Foundational Characteristics of CIOMS and the Common Rule

| Characteristic | CIOMS Guidelines | U.S. Common Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Document | International ethical guidelines | U.S. federal regulation |

| Legal Status | Non-binding, aspirational | Legally binding for covered research |

| Primary Scope | Global; health-related research | U.S.; federally conducted/supported research |

| Philosophical Basis | Declaration of Helsinki; global health justice | Belmont Report; regulatory compliance |

| Regulatory Authority | None (advisory) | OHRP, FDA (for FDA-regulated research) |

| Key Revision Drivers | International expert consensus | Federal rulemaking process |

Structural Comparison and Key Provisions

A detailed analysis of structural elements reveals how each framework organizes its ethical requirements, with significant implications for research implementation and oversight.

Research Ethics Board (REB) Composition and Function

The requirements for ethics committee composition and operation highlight fundamental differences in approach between the two frameworks.

CIOMS REB Composition: CIOMS Guideline 23 mandates multidisciplinary membership with clearly specified categories of expertise. Required members include physicians, scientists, other professionals (nurses, lawyers, ethicists, coordinators), and community members or patient representatives who can represent participants' cultural and moral values. A distinctive feature is the recommendation to include members with personal experience as study participants. The guidelines explicitly state that committees must include both men and women and should invite representatives of relevant advocacy groups when reviewing research involving vulnerable populations. This framework emphasizes the collective competency and diverse perspective of the REB as essential for ethical review [9].

Common Rule IRB Composition: The Common Rule (45 CFR §46.107) specifies that an IRB must have at least five members with varying backgrounds. The composition must include at least one scientist, one non-scientist, and one member who is not otherwise affiliated with the institution. The regulation emphasizes that no IRB may consist entirely of men or women, and it must include representatives from diverse racial and cultural backgrounds. It also requires the IRB to be sufficiently qualified through the experience and expertise of its members to promote respect for its advice and counsel. The requirements are more focused on structural composition and conflict of interest avoidance rather than specific experiential backgrounds [9] [34].

Scope and Applicability

The domains of research covered by each framework differ substantially, reflecting their distinct purposes.

CIOMS Scope: The guidelines apply broadly to "health-related research involving humans," a comprehensive category that encompasses clinical, biomedical, and health-related socio-behavioral research. Their applicability is universal in intent, designed to provide guidance for any country seeking to establish or strengthen ethical review standards, with particular relevance for resource-limited settings [9] [33].

Common Rule Scope: The Common Rule applies specifically to "human subjects research" that is conducted or supported by any U.S. federal department or agency that has adopted the policy. It also applies to research that is submitted to the FDA as part of a marketing application for drugs or biological products, regardless of funding source. The definition of "human subject" focuses on a living individual about whom an investigator obtains data through intervention or interaction, or identifiable private information. This creates a more legally circumscribed domain of application [34].

Analytical Framework for Empirical Ethics Research

Evaluating the practical implementation of these frameworks requires robust empirical ethics research methodologies. The "road map" of quality criteria for empirical ethics provides a structured approach for such comparative analysis [19].

Quality Criteria for Empirical Ethics Research

Empirical ethics research integrates descriptive empirical methodologies with normative ethical analysis, requiring specific quality standards to ensure methodological rigor and ethical relevance.

- Primary Research Question: The research question must clearly bridge empirical inquiry and normative analysis, specifying how data collection will inform ethical evaluation of the frameworks.

- Theoretical Framework and Methods: The study must employ a sound empirical methodology (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) appropriate for the research question, while also making explicit the normative ethical framework (e.g., principism, capabilities approach) used for analysis.

- Relevance: The research must demonstrate practical significance for REB/IRB operations, regulatory policy, or the protection of research participants, moving beyond purely theoretical discussion.

- Interdisciplinary Research Practice: The research process should facilitate genuine integration between empirical and normative dimensions, avoiding the mere juxtaposition of descriptive findings with ethical conclusions.

- Research Ethics and Scientific Ethos: The empirical investigation itself must adhere to rigorous ethical standards, including appropriate review, informed consent, confidentiality, and reflexivity about researcher positionality [19].

Experimental Protocol for Framework Comparison

The following protocol provides a methodological template for conducting empirical comparisons of ethical frameworks in practice.

Objective: To systematically compare the implementation of CIOMS guidelines and Common Rule requirements in REB/IRB review processes and outcomes.

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Identify multiple REBs/IRBs operating under each framework in comparable research institutions.

- Data Collection:

- Document Analysis: Systematically review REB/IRB standard operating procedures, membership rosters, and training materials.

- Structured Observation: Observe REB/IRB meetings reviewing identical simulated research protocols.

- Surveys and Interviews: Administer validated questionnaires and conduct semi-structured interviews with REB/IRB members and researchers.

- Variables Measured:

- REB/IRB Composition: Demographic diversity, expertise domains, member experience.

- Review Process Characteristics: Time to approval, number of revisions requested, specific concerns raised.

- Decision-Making Patterns: Emphasis on scientific, ethical, or regulatory considerations in deliberations.

- Participant Perspective Integration: Frequency and nature of community member contributions.

Analysis:

- Quantitative: Compare composition metrics and review outcomes using statistical methods (e.g., t-tests, chi-square).

- Qualitative: Employ thematic analysis to identify patterns in deliberation content and decision-making rationales.

- Integration: Synthesize quantitative and qualitative findings to evaluate how framework differences manifest in practical outcomes.

Conceptual Workflow for Empirical Ethics Research

The diagram below illustrates the integrated process for conducting empirical ethics research comparing ethical frameworks.

Comparative Analysis of Key Provisions

Direct comparison of specific provisions reveals how each framework addresses core ethical requirements, with implications for research implementation and participant protection.

Table 2: Detailed Comparison of Key Ethical Provisions

| Ethical Requirement | CIOMS Guidelines | U.S. Common Rule | Practical Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent | Emphasizes contextual adaptation and cultural appropriateness; requires understanding assessment. | Standardized required elements; specific regulatory language; waiver provisions under certain conditions. | CIOMS offers flexibility for diverse settings; Common Rule ensures consistency but may lack cultural nuance. |

| Vulnerable Populations | Explicit recognition of context-dependent vulnerability; requires special protections and representation. | Specifically enumerates vulnerable categories (pregnant women, prisoners, children); subparts B-D provide additional regulations. | CIOMS approach is more fluid and inclusive; Common Rule provides specific but potentially limited categorization. |

| Community Engagement | Strong emphasis on community consultation and participation in research design and review. | Limited requirements for community representation in IRB composition; no mandatory community consultation. | CIOMS promotes deeper stakeholder involvement; Common Rule focuses primarily on procedural representation. |

| Post-Trial Obligations | Explicitly addresses post-trial access to beneficial interventions; global fairness focus. | No specific requirement for post-trial access provision; focuses primarily on trial period protections. | CIOMS promotes greater responsibility for research sustainability; Common Rule limits obligations to study duration. |

| Training Requirements | Emphasizes continuous education and knowledge updating for all REB members. | Requires education on regulatory requirements but less emphasis on ongoing ethical training. | CIOMS supports deeper ethical deliberation capacity; Common Rule ensures regulatory compliance knowledge. |

Researchers conducting empirical studies on ethical frameworks require specific conceptual and methodological tools. The following table outlines key resources for rigorous investigation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Empirical Ethics Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in Empirical Ethics Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Survey Instruments | Quantitatively measure REB/IRB member attitudes, perceptions, and experiences with ethical frameworks. | Assessing member confidence in reviewing specific protocol types across different regulatory environments. |

| Structured Observation Protocols | Systematically document REB/IRB deliberation dynamics, communication patterns, and decision-making processes. | Comparing how scientific vs. ethical considerations are weighted in deliberations under different frameworks. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | Explore in-depth perspectives on implementation challenges, interpretive differences, and practical impacts. | Understanding how REB/IRB chairs navigate ambiguities in ethical guidelines when reviewing complex protocols. |

| Simulated Research Protocols | Standardized research scenarios used to evaluate consistency of review outcomes across different REBs/IRBs. | Testing how identical research proposals are evaluated under CIOMS-guided vs. Common Rule-guided review. |

| Document Analysis Frameworks | Systematically code and analyze REB/IRB policies, minutes, and correspondence for comparative assessment. | Identifying differences in required consent form elements and review procedures across regulatory frameworks. |

| Normative Analysis Frameworks | Provide structured approaches for evaluating the ethical implications of empirical findings. | Applying ethical principles to assess the practical implementation differences identified through empirical research. |

The comparative analysis reveals that CIOMS guidelines and the Common Rule represent complementary but distinct approaches to research ethics governance. CIOMS offers a flexible, principle-based framework with strong emphasis on contextual adaptation, community engagement, and global applicability, making it particularly valuable for international research and resource-limited settings. In contrast, the Common Rule provides a detailed, legally binding regulatory framework that ensures standardized protections and procedural compliance within the U.S. research context.

For researchers and ethics committee members operating in a globalized research environment, understanding these distinctions is essential for designing ethically sound studies that satisfy multiple regulatory standards. The optimal approach often involves applying the universal principles of CIOMS within the specific regulatory requirements of the Common Rule where applicable. Future empirical research should continue to examine how these frameworks interact in practice, particularly as international collaborative research increases and regulatory systems continue to evolve. The quality criteria for empirical ethics research provide a robust methodology for conducting these important comparative investigations [19].

Implementing Rigorous Methods: Standards and Reporting Frameworks

Empirical ethics research provides critical insights into complex healthcare dilemmas, bridging descriptive evidence and normative reflection [19]. This interdisciplinary field, which integrates methodologies from social sciences with philosophical analysis, has seen substantial growth; one quantitative analysis of nine bioethics journals revealed a statistically significant increase in empirical research publications from 1990 to 2003 [7]. However, this expansion has surfaced persistent methodological concerns, particularly regarding how to maintain scientific rigor while responding to urgent ethical questions in real-time.

The emergence of rapid evaluation approaches addresses the critical factor of timeliness in influencing the utility of research findings, especially in contexts like humanitarian crises, evolving health services, or global health emergencies [35]. These approaches are characterized by their short duration, use of multiple data collection methods, team-based research structures, and formative designs that provide actionable findings to policymakers and practitioners [35]. Despite their potential, rapid methods face significant challenges including questions about validity, reliability, and representativeness due to compressed timeframes, potentially leading to unfounded interpretations and conclusions [35].

To address these challenges, the STREAM (Standards for Rapid Evaluation and Appraisal Methods) framework was developed through a rigorous consensus process [35]. This framework establishes methodological standards specifically designed for rapid research contexts, providing guidance for improving transparency, completeness of reporting, and overall quality of rapid studies [36]. For empirical ethics researchers, STREAM offers a structured approach to navigating the tension between methodological rigor and practical urgency, ensuring that rapid findings maintain scientific integrity while remaining responsive to pressing ethical dilemmas.

Understanding the STREAM Framework

Development and Structure

The STREAM framework was developed through a meticulous four-stage consensus process designed to incorporate diverse expert perspectives [35]. The development methodology began with a steering group consultation, followed by a three-stage e-Delphi study involving stakeholders with experience in conducting, commissioning, or participating in rapid evaluations [35]. This process culminated in a stakeholder consensus workshop and a piloting exercise to refine the standards for practical application [35]. The e-Delphi study employed strict consensus thresholds, requiring 70% or more of participants to rate an item as relevant with 15% or less rating it as irrelevant for inclusion [35].

Through this rigorous process, 38 distinct standards were established, organized to guide the entire research lifecycle from initial design through implementation and reporting [35]. These standards address fundamental concerns in rapid research methodology, including transparency in reporting, maintaining methodological rigor, ensuring ethical practice, and enhancing the validity and utility of findings produced within compressed timeframes [35]. The framework is designed to be flexible enough to accommodate various rapid evaluation approaches while establishing clear benchmarks for quality.

Scope and Application

STREAM is intentionally designed for broad application across multiple research contexts and methodologies [36]. The framework applies to observational studies, qualitative research, mixed-methods approaches, and service quality improvement studies—essentially any research形式 utilizing rapid evaluation approaches [36]. This breadth of application makes it particularly valuable for empirical ethics research, which often employs diverse methodological approaches to address complex normative questions.

The framework serves three primary functions for researchers: (1) as guidelines for designing and implementing rapid evaluations and appraisals; (2) as reporting templates to ensure complete and transparent documentation of methods; and (3) as a quality assessment tool for evaluating existing rapid studies [36]. This multi-function approach addresses the critical need for standardized reporting in rapid research, where adaptations and methodological shortcuts can sometimes obscure important limitations or methodological decisions [35].

For empirical ethics researchers operating in time-sensitive contexts, STREAM provides a structured approach to maintaining scientific integrity while delivering timely findings. The framework helps researchers navigate common challenges in rapid research, such as balancing breadth and depth of data collection, managing team-based variability in data interpretation, and ensuring representative sampling despite shorter fieldwork periods [35].

Comparative Analysis: STREAM Versus Alternative Approaches

Methodological Comparison

When evaluated against other methodological standards, STREAM demonstrates distinct characteristics tailored specifically to the challenges of rapid research. Unlike broader empirical ethics quality criteria, which provide a "road map" of reflective questions across categories like primary research question, theoretical framework, relevance, and interdisciplinary practice [19], STREAM offers concrete, actionable standards for maintaining rigor within time-constrained environments.

The following table compares STREAM's key characteristics with general quality criteria for empirical ethics research and traditional non-rapid methodological standards:

Table 1: Comparison of STREAM with Alternative Methodological Approaches

| Aspect | STREAM Framework | General Empirical Ethics Quality Criteria [19] | Traditional Non-Rapid Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Consideration | Explicitly designed for compressed timelines | Time-neutral | Assumes extended timeframes |

| Methodological Flexibility | High flexibility with transparency requirements | Methodology-dependent | Often methodology-specific |

| Integration of Empirical & Normative | Implicit in design for ethics contexts | Explicit focus on integration | Often separate processes |

| Transparency Emphasis | High focus on reporting adaptations | Moderate focus on transparency | Standardized reporting |

| Primary Application | Rapid evaluations, appraisals, assessments | Broad empirical ethics research | Discipline-specific research |

| Development Process | Formal Delphi study & consensus workshop [35] | Theoretical analysis & working group [19] | Various development methods |

STREAM's development process represents a significant strength, employing rigorous consensus-building methods that incorporated diverse stakeholder perspectives [35]. The framework addresses a critical gap in methodological standards, as no previously published guidelines specifically focused on rapid evaluations and appraisals existed before STREAM's development [35].

Application in Empirical Ethics

For empirical ethics research, STREAM addresses specific methodological challenges that distinguish it from other approaches. While general quality criteria for empirical ethics emphasize the integration of descriptive and normative statements and the importance of interdisciplinary team work [19], STREAM provides practical guidance on maintaining this integration under time constraints.

A key advantage of STREAM for empirical ethics is its explicit attention to validity threats unique to rapid methodologies. These include short-term data collection periods that may miss evolving ethical perspectives, reliance on easily accessible participants potentially lacking diversity of viewpoints, compressed analysis periods allowing limited critical reflection, and variability in team-based data interpretation [35]. By addressing these threats through standardized practices, STREAM helps empirical ethics researchers produce findings with greater methodological integrity.

Unlike discipline-specific guidelines, STREAM's broad applicability makes it particularly valuable for the inherently interdisciplinary nature of empirical ethics, which combines methodologies from social sciences with normative analysis [19]. The framework facilitates the "analytical distinction between descriptive and normative statements" that is essential for evaluating their validity in empirical ethics research [19], while providing guidance on maintaining this distinction when working within compressed timeframes.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

STREAM Development Methodology

The experimental protocol for developing the STREAM framework was characterized by rigorous, systematic consensus-building. The process began with a comprehensive systematic review to identify methods used to ensure rigor, transparency, and validity in rapid evaluation approaches [35] [37]. This review informed the initial list of items for the e-Delphi study, which was further refined through steering group consultation [35].

The e-Delphi study implemented a structured three-round survey process using the Welphi platform, with invitations extended to 283 potential participants identified through purposive sampling [35]. The participant selection criteria specifically included stakeholders with experience in "conducting, participating, reviewing or using findings from rapid studies" [35], ensuring that the resulting standards were grounded in practical expertise. The target sample size of 50-80 participants accounted for anticipated attrition across rounds [35].

Following the Delphi process, a stakeholder consensus workshop was conducted in June 2023 to refine the clarity and practical application of the standards [35]. The final validation stage involved a piloting exercise to understand STREAM's validity in practice [35]. This multi-stage development methodology aligns with established protocols for reporting guideline development, including registration on the EQUATOR network and publication of a protocol on the Open Science Framework [35].

Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential development and implementation process for the STREAM framework:

Validation Outcomes

The validation process for STREAM demonstrated its practical utility across multiple dimensions. The e-Delphi study achieved consensus on 38 standards through its structured ranking process, where participants rated each statement's relevance on a 4-point Likert scale [35]. The piloted implementation of STREAM allowed researchers to assess the framework's viability in actual research settings, leading to refinements that enhanced its practical application [35].

Unlike earlier approaches to empirical ethics quality that provided primarily theoretical guidance [19], STREAM's development incorporated empirical testing and iterative refinement. The framework addresses specific methodological shortcomings identified in prior research, including the lack of transparency in rapid study methods and adaptations made throughout the research process [35]. This empirical grounding in both development and validation distinguishes STREAM from more theoretically-derived quality criteria.

Essential Research Toolkit for Implementation

Implementing the STREAM framework effectively requires utilizing specific methodological tools and approaches. The following research reagent solutions provide the essential components for applying STREAM standards to rapid evaluation projects in empirical ethics research:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for STREAM Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in STREAM Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Consensus Building Tools | e-Delphi Platform (e.g., Welphi) | Facilitates structured expert consensus on methodological standards [35] |

| Reporting Guidelines | EQUATOR Network Standards | Enhances transparency and completeness of reporting [35] |

| Protocol Registries | Open Science Framework (OSF) | Provides public study registration and protocol documentation [35] |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Consensus Workshops | Enables collaborative refinement of standards [35] |

| Piloting Frameworks | Field Testing Protocols | Validates practical application of standards in diverse contexts [35] |

| Systematic Review Methods | PRISMA-guided Reviews | Identifies methodological gaps and best practices [37] |

These research reagents collectively address the core challenges in rapid evaluation methodologies. The consensus-building tools enable the development of standardized approaches that maintain flexibility for different research contexts. Reporting guidelines and protocol registries directly address the transparency issues that have plagued rapid research, where methodological adaptations often go unreported [35]. Stakeholder engagement mechanisms ensure that the resulting standards remain grounded in practical research realities rather than theoretical ideals.