Ethical Safeguards: A Comprehensive Guide to the Informed Consent Process for Vulnerable Populations in Clinical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a strategic framework for navigating the ethical and practical complexities of obtaining informed consent from vulnerable populations.

Ethical Safeguards: A Comprehensive Guide to the Informed Consent Process for Vulnerable Populations in Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a strategic framework for navigating the ethical and practical complexities of obtaining informed consent from vulnerable populations. Covering foundational principles from regulatory policy to contemporary analytical models of vulnerability, the guide details adaptable methodologies for diverse groups, proactive solutions for common challenges like comprehension barriers and power dynamics, and validation techniques to ensure process integrity. By synthesizing current guidelines and evidence-based strategies, this resource aims to equip clinical teams to uphold the highest standards of ethical research while promoting equitable participation.

Understanding Vulnerability and Ethical Frameworks in Human Subjects Research

In the context of research ethics, vulnerability represents a multifaceted concept critical to the protection of human subjects. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as "the quality of being susceptible to harm, influence, or attack" [1]. Within healthcare research, vulnerability is often associated with a perceived loss of power relative to others, coupled with heightened exposure to various risks, including physical, psychological, emotional, cultural, and economic threats [1]. This sense of vulnerability intensifies with diminished self-confidence and challenges in navigating unfamiliar health-related situations [1]. For researchers, understanding and properly assessing vulnerability is essential for implementing ethical safeguards, particularly during the informed consent process, ensuring that care and research protocols are tailored to the unique needs of each individual.

The Common Rule, a federal standard of ethics, oversight, and transparency in government-funded research involving human subjects, specifically contains provisions to protect particular vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, human fetuses, prisoners, and children [2]. Historically, vulnerability was often approached through a categorical lens, identifying specific groups considered at risk. However, modern frameworks recognize vulnerability as a dynamic state that requires analytical assessment rather than simple group classification. This shift enables researchers to better protect participants through tailored consent processes and study designs that address their specific circumstances and capacities.

Vulnerability Categories and Assessment Frameworks

Categorical Groups of Vulnerable Populations

Vulnerable populations in clinical research settings refer to groups of people who can be harmed, manipulated, coerced, or deceived by unscrupulous researchers because of their limited decision-making ability, lack of power, or disadvantaged status [3]. These populations include children, prisoners, individuals with impaired decision-making capacity, or those who are economically or educationally disadvantaged [3]. Aday's seminal work highlighted several populations considered particularly vulnerable, including high-risk mothers and infants, the chronically ill and disabled, individuals with AIDS, those with mental illnesses, alcohol or substance abusers, individuals prone to suicide or homicide, abusive families, the homeless, and immigrants and refugees [1].

Table 1: Traditional Categorical Vulnerable Populations in Research

| Population Category | Key Vulnerability Factors | Common Ethical Concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Children | Limited capacity for understanding; legal inability to provide consent | Coercion by authority figures; inability to comprehend risks |

| Prisoners | Restricted autonomy; potential for undue influence | Perceived coercion to participate; limited alternatives |

| Economically Disadvantaged | Financial pressures; limited access to healthcare | Undue inducement; unequal benefits distribution |

| Cognitively Impaired | Diminished decision-making capacity | Challenges assessing understanding; potential for exploitation |

| Seriously Ill Patients | Desperation for treatment; therapeutic misconception | Overestimation of benefits; underestimation of risks |

Analytical Frameworks for Vulnerability Assessment

Moving beyond categorical approaches, modern vulnerability assessment employs multidimensional frameworks that evaluate various contributing factors. Havrilla defines vulnerability as "a state of dynamic openness and opportunity for individuals, groups, communities, or populations to respond to community and individual factors through the use of internal and external resources in a positive (resilient) or negative (risk) manner along a continuum of illness (oppression) to health (growth)" [1]. This conceptualization acknowledges vulnerability as a dynamic state rather than a fixed characteristic, emphasizing the continuum along which individuals may move based on available resources and support systems.

The shift from categorical to analytical frameworks represents a significant evolution in research ethics. Rather than applying predetermined protections based solely on group membership, researchers now assess individual circumstances, contextual factors, and specific research demands. This approach allows for more tailored safeguards that address actual rather than presumed vulnerabilities. Analytical frameworks consider intersecting factors such as decision-making capacity, situational pressures, understanding of research concepts, and power differentials that may affect a participant's ability to provide truly informed consent.

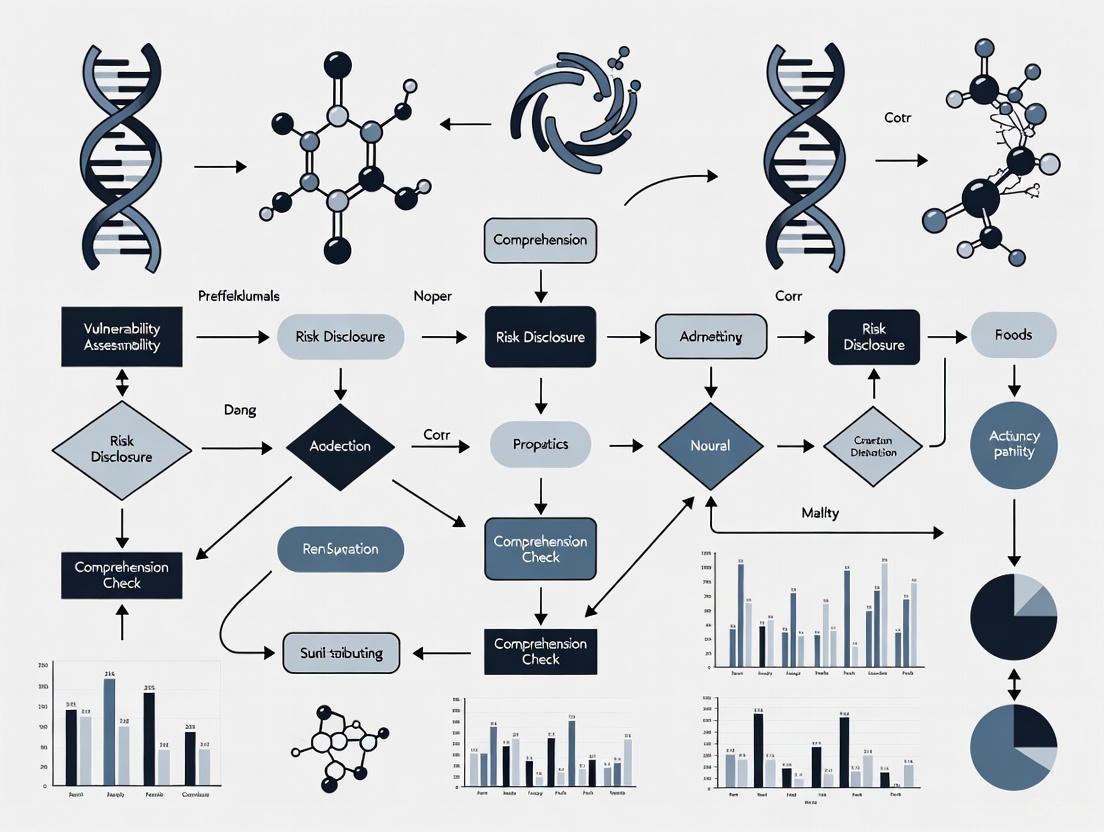

Diagram 1: Analytical Framework for Vulnerability Assessment in Research. This diagram illustrates the multidimensional factors contributing to vulnerability assessment and their relationship to tailored consent processes and ethical research participation.

Application Notes: Vulnerability Assessment Instruments and Protocols

Available Vulnerability Assessment Instruments

A recent scoping review identified 13 distinct instruments used to assess vulnerability at the individual and/or family level in healthcare contexts [1]. These instruments vary widely in terms of dimensions, number of items, target populations, and modes of completion. Some instruments focus on specific aspects such as socioeconomic status, health behaviors, or access to services [1]. The review demonstrates the complexity of the vulnerability concept and the need for instruments adapted to specific determinants/factors, such as environmental, biological, and social factors, as well as the specificities of target populations and contexts of assessment and intervention.

Table 2: Characteristics of Vulnerability Assessment Instruments in Healthcare Research

| Instrument Name | Target Population | Key Assessment Domains | Completion Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerable Elders Survey | Older adults | Functional status, self-rated health, age | Self-report or interviewer-administered |

| Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) | General population | Socioeconomic status, household composition, disability, minority status, housing/transportation | Composite index from existing data |

| Perceived Vulnerability Scale (PVS) | Adults | Subjective perception of vulnerability to health threats | Self-report |

| Vulnerability Scale for the Elderly (VSE) | Older adults | Social support, economic resources, health status, environmental factors | Interviewer-administered |

| HRCA Vulnerability Index | Older adults | Physical health, functional capacity, social resources | Professional assessment |

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive Vulnerability Assessment for Informed Consent

Protocol Objectives and Scope

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for assessing vulnerability factors that may impact the informed consent process in research involving human subjects. The primary objective is to identify individual-specific vulnerability factors that might compromise a potential participant's ability to provide voluntary, informed consent. The assessment follows a multidimensional approach that considers decision-making capacity, situational factors, understanding, and power differentials rather than relying solely on categorical group membership.

The protocol applies to all potential research participants, with particular attention to populations historically classified as vulnerable. The assessment should be conducted by trained research staff familiar with research ethics and vulnerability concepts, ideally during the initial screening process before the formal consent discussion begins. The outcome informs modifications to the consent process to ensure comprehension and voluntariness.

Materials and Equipment

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Vulnerability Assessment

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability Assessment Tool | Standardized instrument to evaluate vulnerability dimensions | Select instrument based on population and research context; ensure cultural appropriateness |

| Decision-Making Capacity Assessment | Structured evaluation of understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and choice | Use validated tools such as MacCAT-CR or UBACC for clinical trials |

| Understanding Assessment Tool | Measure comprehension of research concepts | Develop study-specific quiz with key elements; aim for 100% comprehension |

| Environmental Assessment Checklist | Evaluate context where consent is obtained | Assess privacy, comfort, time pressure, and potential coercive influences |

| Cultural/Linguistic Support Materials | Facilitate communication across language and cultural barriers | Professional interpreters, translated materials at appropriate literacy levels |

Step-by-Step Procedures

Step 1: Pre-Assessment Preparation (Time: 15-20 minutes)

- Review the proposed research protocol to identify potential vulnerability factors specific to the study (e.g., complex procedures, high risk, novel interventions)

- Select appropriate assessment instruments based on the target population and research context

- Prepare the physical environment to ensure privacy and comfort for the assessment

- Arrange for interpretation services or specialized communication assistance if needed

Step 2: Initial Screening (Time: 10-15 minutes)

- Conduct a preliminary assessment of demographic and situational factors

- Identify obvious categorical vulnerabilities (e.g., cognitive impairment, limited English proficiency)

- Determine if additional resources are needed for the full assessment

- Document initial observations in the research record

Step 3: Multidimensional Assessment (Time: 20-30 minutes)

- Administer selected vulnerability assessment instruments using standardized procedures

- Evaluate decision-making capacity using structured tools if indicated

- Assess understanding of basic research concepts through simple explanation and questioning

- Identify situational pressures that might affect participation decisions

- Document all assessment results using standardized forms

Step 4: Analysis and Interpretation (Time: 15-20 minutes)

- Review assessment results to identify specific vulnerability factors

- Determine the magnitude and nature of potential vulnerabilities

- Assess how identified vulnerabilities might impact the consent process

- Develop recommendations for consent process modifications

- Document the analysis and recommendations

Step 5: Consent Process Tailoring (Time: Variable)

- Implement recommended modifications to the consent process

- This may include: simplified consent forms, extended discussion time, use of multimedia materials, involvement of surrogate decision-makers, additional educational sessions

- Ensure all modifications are documented and approved by the IRB if required

Step 6: Ongoing Monitoring (Time: Throughout study participation)

- Continuously assess for emerging vulnerabilities during study participation

- Monitor understanding retention at regular intervals

- Be alert to changes in circumstances that might create new vulnerabilities

- Document and address any new vulnerability concerns promptly

Diagram 2: Vulnerability Assessment Workflow for Informed Consent. This diagram outlines the sequential steps for conducting a comprehensive vulnerability assessment to support ethical informed consent processes in research with human subjects.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Analysis of vulnerability assessment data should focus on identifying specific barriers to informed consent rather than simply categorizing individuals as vulnerable or not. Quantitative data from standardized instruments should be interpreted according to established cutoff scores where available. Qualitative observations should be systematically reviewed for patterns indicating potential vulnerabilities. The overall assessment should result in a vulnerability profile that identifies specific factors requiring accommodation in the consent process.

Key interpretation principles include:

- Consider vulnerabilities as context-specific rather than absolute

- Recognize that multiple minor vulnerabilities may have cumulative effects

- Assess the interaction between different vulnerability factors

- Prioritize vulnerabilities that directly impact decision-making capacity or voluntariness

- Consider compensatory strengths and resources the individual may possess

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common challenges in vulnerability assessment include:

- Resistance from participants who may feel stigmatized by the assessment: Address by normalizing the process and emphasizing its protective purpose

- Discrepancies between different assessment tools: Resolve through clinical judgment and consideration of the specific research context

- Time constraints in busy clinical settings: Optimize by using brief screening tools followed by targeted in-depth assessment when needed

- Cultural or linguistic barriers: Address through use of validated translated instruments and professional interpreters

- Uncertainty in interpretation: Consult with ethics committee or colleagues experienced in vulnerability assessment

Discussion: Implications for Research Ethics and Practice

The evolution from categorical to analytical frameworks for understanding vulnerability has significant implications for research ethics and practice. Modern approaches recognize that vulnerability exists on a continuum and is influenced by multiple interacting factors [1]. This perspective allows for more nuanced and individualized protection of research participants while facilitating appropriate inclusion of potentially vulnerable populations.

Current regulations acknowledge the need for special protections for vulnerable populations. The Common Rule specifically contains provisions to protect particular vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, human fetuses, prisoners, and children [2]. However, an analytical approach complements these categorical protections by requiring researchers to assess individual vulnerability factors regardless of group membership. This is particularly important for individuals who may experience vulnerability due to intersecting factors that don't fit neatly into predefined categories.

The development of validated assessment instruments provides researchers with practical tools to implement analytical vulnerability assessment [1]. These instruments enable systematic evaluation of vulnerability factors rather than reliance on intuition or assumptions. However, instrument selection must be guided by consideration of the specific research context and population, as no single tool is appropriate for all situations.

Engaging vulnerable populations in research requires careful attention to ethical safeguards while avoiding inappropriate exclusion. As noted by Dr. Muhammad Waseem, "While vulnerable populations are considered at higher risk of harm or injustice in research, since they often cannot protect themselves through valid informed consent, they are also underrepresented and underserved in clinical research" [3]. Excluding vulnerable populations from research can perpetuate health disparities by limiting the generalizability of findings and access to potentially beneficial experimental treatments.

The analytical framework presented in this document provides a structured approach to vulnerability assessment that supports ethical inclusion of vulnerable populations through tailored consent processes and ongoing monitoring. This approach respects the principles of justice, beneficence, and respect for persons that form the foundation of research ethics, while advancing scientific validity through appropriate inclusion of diverse populations.

The Belmont Report, published in 1979, established the foundational ethical principles for conducting research involving human subjects in the United States. Its creation was prompted by historical ethical abuses, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and it continues to shape modern research ethics [4]. The Report's principles were later operationalized into federal regulations through the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, commonly known as the Common Rule (45 CFR part 46) [4]. The relationship between these guidelines and evolving international standards is critical for today's researchers, particularly when developing protocols for vulnerable populations who require additional protections. Recent regulatory trends in 2025 show agencies like the FDA and EMA increasing their focus on ensuring these populations are protected with stricter ethical and procedural safeguards [5] [6]. This document outlines application notes and detailed protocols for navigating this complex regulatory environment, with a specific focus on obtaining ethically valid informed consent from vulnerable participants.

Core Ethical Principles and Regulatory Frameworks

The Belmont Report's Three Ethical Pillars

The Belmont Report elucidates three core ethical principles that must govern all human subjects research [4]:

- Respect for Persons: This principle acknowledges the autonomy of individuals and requires protecting those with diminished autonomy. It mandates that subjects enter research voluntarily and with adequate information, forming the bedrock of the informed consent process.

- Beneficence: This principle extends beyond "do no harm" to maximizing possible benefits and minimizing potential risks. It requires a systematic assessment of all research risks and benefits.

- Justice: This principle addresses the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research. It requires that the selection of subjects be scrutinized to avoid systematically recruiting vulnerable populations simply for administrative convenience or due to their compromised position.

The Common Rule: Operationalizing Ethics

The Common Rule translates the ethical principles of Belmont into enforceable regulations for IRBs, sponsors, and investigators [4]. Key revisions that impact research involving vulnerable populations include:

- Informed Consent Revisions: The revised Common Rule requires that consent forms begin with a "concise and focused presentation of key information" to help prospective subjects understand reasons for or against participation. The form must be organized to facilitate comprehension [7].

- Exempt Research Categories: The Rule outlines categories of research that may be exempt from full IRB review. Several categories were modified or added, some of which have specific provisions for collecting identifiable, sensitive information, requiring IRBs to ensure adequate privacy and confidentiality safeguards are in place [7].

- Elimination of Continuing Review: For many minimal-risk studies that have progressed to data analysis or are eligible for expedited review, continuing review is no longer mandated. However, IRBs retain the discretion to require it for studies with specific risk profiles, such as those conducted internationally or where non-compliance is a concern [7].

International Harmonization and 2025 Trends

Globally, regulatory agencies are working to harmonize standards. The International Council for Harmonisation's (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R3) maintains ties to the ethical framework of the Belmont Report [4]. Key 2025 trends include:

- Increased Focus on Vulnerable Populations: Regulatory bodies like the U.S. HHS and FDA are refining guidelines and regulations for protecting children, pregnant women, prisoners, and other vulnerable groups. This drive for harmonization aims to simplify ethical reviews and provide consistent oversight while ensuring the highest protection standards [6].

- Patient-Centricity: The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is prioritizing patient engagement, including integrating patient-reported outcomes in trials and involving patient advocacy groups early in development [8].

- Decentralized Trials and Technology: Following the pandemic, models like decentralized and hybrid clinical trials are being promoted to improve access and convenience. This involves using digital platforms and wearable devices, which must be implemented with careful attention to the digital literacy and access of vulnerable participants [8].

Table 1: Core Ethical Principles and Their Application to Vulnerable Populations

| Ethical Principle (Belmont) | Regulatory Manifestation (Common Rule/ICH) | Application to Vulnerable Populations |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Informed consent process; documentation of voluntary participation [4] [7]. | Requires assessments of decisional capacity; use of legally authorized representatives; and assent procedures for children or adults with impaired capacity. |

| Beneficence | Thorough risk-benefit analysis by IRB; ongoing monitoring of safety data [4]. | Demands stringent justification for including vulnerable individuals in research, ensuring risks are justified by potential benefits to them or their population. |

| Justice | Equitable selection of subjects; scrutiny of recruitment methods [4]. | Protects against the systematic over-use of vulnerable groups for convenience and promotes fair access to the benefits of research. |

Application Notes: Implementing Ethical Protocols for Vulnerable Populations

Implementing the Belmont principles and Common Rule requirements demands careful, practical planning. The following notes address key application areas.

Defining and Identifying Vulnerability

Vulnerability in research arises from a potential for exploitation due to an impaired ability to protect one's own interests. Key populations include [5]:

- Children and minors

- Pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates

- Prisoners and incarcerated persons

- Individuals with cognitive or intellectual disabilities

- Economically or educationally disadvantaged persons

- Patients in emergency settings

Application Note 1.1: Vulnerability is context-specific. A university professor may be vulnerable in a study related to a life-threatening personal illness, while a prisoner may not be vulnerable in a study on social structures if their participation is truly voluntary and anonymous. The protocol must justify the specific population and describe the additional safeguards implemented.

The Enhanced Informed Consent Process

For vulnerable populations, the consent process is an ongoing dialogue, not a single event. Key elements include [5]:

- Capacity Assessment: Implement a brief, validated tool to assess a potential subject's understanding of the study's key elements, especially for populations with fluctuating or questionable capacity.

- Process Consent: For individuals with progressive cognitive disorders, re-evaluate understanding at regular intervals throughout the study.

- Assent and Respect: Even when formal consent is provided by a representative, seek the affirmative agreement (assent) of the individual if they have some level of understanding. Respect any signs of dissent.

- Witnesses and Advocates: Utilize independent, unaffiliated witnesses or patient advocates during the consent discussion to ensure the process is free from coercion and that information is adequately conveyed.

Experimental Protocols: Consent and Oversight Workflows

Protocol: Developing an Informed Consent Plan for a Vulnerable Population

Objective: To create a comprehensive, ethically sound informed consent plan for research involving adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" in Section 5.

Methodology:

Pre-Study Phase

- IRB Consultation: Engage with the IRB early to discuss the population, justification for inclusion, and the proposed consent process. Determine if a waiver of some consent elements is possible or required.

- Consent Form Development: Draft the consent form using plain language at a 6th-grade reading level. Adhere to the revised Common Rule requirement by starting with a concise summary of key information (purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, alternatives). Use large, legible fonts (e.g., 14-point).

- Capacity Assessment Tool Selection: Select and validate a brief capacity assessment tool (e.g., the University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent [UBACC]) to be administered prior to the full consent discussion.

Consent Execution Phase

- Environment Setting: Conduct the consent discussion in a quiet, private, and comfortable environment free from distractions.

- Participant and Representative Presence: The potential participant must be present with their legally authorized representative (LAR).

- Information Disclosure: The investigator explains the study, using the simplified consent form and any auxiliary aids (e.g., pictograms, videos).

- Teach-Back Method: After explaining a key concept (e.g., "randomization"), ask the participant to explain it back in their own words to confirm understanding.

- Capacity Assessment: The study coordinator administers the brief capacity tool.

- Decision and Documentation: Based on the capacity assessment, the primary consent is provided by either the participant (if deemed capable) or the LAR. The participant's assent is sought regardless. All parties present, including the witness, sign and date the consent form.

Ongoing Consent Process

- Re-assessment Triggers: Define criteria for re-assessing consent capacity (e.g., significant decline in clinical status, before a new invasive procedure).

- Continuing Communication: Provide a "Consent Passport" — a wallet-sized card with the study contact information and key facts — to the participant and their caregiver.

The following workflow diagrams the key decision points and procedures in this enhanced consent process.

Protocol: Implementing a Single IRB (sIRB) Model for Multi-Site Research

Objective: To streamline the ethical review process for a multi-site clinical trial involving pregnant women, ensuring consistent application of protections for this vulnerable population.

Materials: sIRB Reliance Agreement templates; Central IRB contact information; Study protocol and consent documents.

Methodology:

- Determination of sIRB of Record: The lead study sponsor, in consultation with site investigators, identifies and selects the sIRB of record. This is often a central, commercial IRB with specific expertise in the relevant therapeutic area and vulnerable population.

- Reliance Agreements: Each participating research site executes a formal reliance agreement with the sIRB of record. This agreement cedes the local IRB's review authority for this study to the sIRB, while the local institution retains responsibility for local context issues (e.g., site investigator qualifications, local resources).

- Single Submission and Review: The study sponsor submits the complete protocol, informed consent documents, and recruitment materials to the sIRB of record for initial review.

- Local Context Review: While the sIRB reviews the overall ethical soundness of the study, the local IRB at each site conducts a "local context review." This includes assessing cultural and linguistic appropriateness of consent forms, feasibility, and local legal or regulatory requirements.

- Communication and Coordination: The sIRB communicates its approval, required modifications, or disapproval to the study sponsor and all relying sites. All subsequent amendments, continuing reviews, and reportable events are submitted to the sIRB, ensuring harmonized oversight.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing studies involving vulnerable populations, the following "reagents" — essential procedural tools and documents — are critical for ensuring ethical integrity and regulatory compliance.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ethical Research with Vulnerable Populations

| Research 'Reagent' (Tool/Document) | Function & Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) | An individual or judicial body authorized under applicable law to provide consent on behalf of a prospective subject. | Provides informed consent for an adult with advanced dementia to participate in a study on nutrition. |

| Simplified Consent Form with Pictograms | A consent document written at a low reading level, using images to explain complex concepts like randomization or risks. | Enhancing comprehension for participants with intellectual disabilities or low literacy. |

| Capacity to Consent Assessment Tool | A validated, brief questionnaire to objectively assess a potential subject's understanding of key study elements. | The UBACC tool is used to determine if an individual with schizophrenia can consent for themselves. |

| Assent Document | A simplified document, written for the comprehension level of the individual, used to seek affirmative agreement from those who cannot give legal consent. | Obtaining agreement from a 10-year-old child to participate in a pediatric trial. |

| Witness to Consent Process | An impartial third party who observes the entire consent discussion and attests that the information was clearly presented and given voluntarily. | Ensuring the integrity of the consent process for non-literate participants or in settings with a perceived power imbalance (e.g., prison). |

| sIRB Reliance Agreement | A formal document that establishes the ceding of IRB review authority from a local IRB to a central sIRB for a specific study. | Standardizing the ethical oversight of a multi-site clinical trial for a rare disease in children. |

| Vulnerability-Specific SOP | A Standard Operating Procedure that details the extra steps and safeguards required for a specific vulnerable group. | An SOP for recruiting economically disadvantaged participants, detailing compensation fairness and transportation assistance. |

Application Notes: Integrating Core Ethical Principles into Research with Vulnerable Populations

The application of the four core ethical principles—autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice—requires careful consideration and additional safeguards when research involves vulnerable populations. These principles provide a framework for ensuring that the informed consent process is both ethically sound and effective.

Table 1: Core Ethical Principles and Their Application to Informed Consent

| Ethical Principle | Definition | Application to Informed Consent for Vulnerable Populations |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | Respect for an individual's right to self-determination and decision-making [9] [10]. | The foundation for informed consent; requires ensuring genuine understanding and voluntary agreement, free from coercion [9] [11]. |

| Beneficence | The obligation to act for the benefit of others, promoting their welfare [9] [12]. | Requires that the research has a favorable risk-benefit ratio and offers a potential benefit to the participant or their community [9]. |

| Non-Maleficence | The duty to avoid or minimize harm [9] [10]. | Mandates the identification and mitigation of all foreseeable physical, psychological, social, and economic risks [9] [12]. |

| Justice | The duty to treat individuals equitably and fairly [9] [12]. | Requires the fair selection of research participants and ensuring that vulnerable groups are not unduly burdened nor unjustly excluded from the benefits of research [9] [13]. |

Engaging vulnerable populations in research necessitates moving beyond a one-size-fits-all consent form. A contextual and analytical approach is now recommended over a purely categorical one, which simply labels certain groups as vulnerable [13]. This involves a tailored assessment of the specific sources of vulnerability in a given research context. Key considerations include:

- Building Trust: In long-term studies, sustained relationships and recognizing participants’ intrinsic value are critical for genuine consent [14].

- Cultural Relevance: In some cultures, collective decision-making is the norm, and written consent may be perceived as a sign of mistrust. Guidelines must be adapted to local contexts [14].

- Comprehension: Language and literacy barriers, along with power imbalances, present significant challenges that can be mitigated by involving community members and trained interpreters, and by using tools like the "Teach Back Method" [11] [14].

Experimental Protocols for Ethical Consent

Protocol for Developing and Testing Culturally Relevant Consent Materials

Objective: To develop and validate informed consent materials that are accessible, understandable, and culturally appropriate for a specific vulnerable population.

Background: Standard consent forms often fail to account for cultural norms, varying health literacy levels, and diverse communication preferences, which can systematically exclude vulnerable groups from research [14]. This protocol uses a Design Thinking and Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework to create participant-centric solutions [14].

Methodology:

- Co-Development Workshop: Convene a panel including community representatives, cultural brokers, ethicists, and researchers to draft initial consent materials in plain language [14].

- Material Preparation: Create two versions of key consent "snippets" (paragraph-length sections):

- Original: An Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved version.

- Modified: A version rewritten to improve readability by reducing character length and using less complex language [15].

- Participant Testing: Recruit eligible participants from the target population (N=79, for example) [15]. Present them with paired snippets and survey them on:

- Preference for original or modified text.

- Perceived clarity and comprehensiveness.

- Any new questions elicited by the content.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantitative: Use statistical tests (e.g., regression analysis) to determine if preferences are significantly influenced by text length, content topic (e.g., risks), or participant demographics (e.g., age, ethnicity) [15].

- Qualitative: Thematically analyze open-ended feedback to identify recurring concerns and information gaps [15] [14].

Expected Outcomes: Data-driven guidelines for consent form structure and wording tailored to the population. For instance, results may show that participants consistently prefer shorter text for explaining study risks and that consent materials effectively elicit informed questions from prospective participants [15].

Protocol for an Analytical Vulnerability Assessment

Objective: To systematically identify and mitigate context-specific vulnerabilities during the study design and consent process.

Background: Vulnerability is not inherent but can arise from individual circumstances or the research context itself [13] [16]. An analytical framework ensures appropriate, preventive, and respectful measures for all participants.

Methodology:

- Structured Assessment: Evaluate the research protocol against eight categories of vulnerability [16]:

- Cognitive/Communicative: Inability to process or understand consent information due to language, literacy, or mental capacity.

- Institutional: Subordination to a formal authority (e.g., prisoners, students).

- Deferential: Informal subordination (e.g., patient to doctor, spouse to spouse).

- Medical: Illness may cloud judgment or create undue influence.

- Economic: Payment may induce undue risk-taking.

- Social: Risk of discrimination based on race, gender, etc.

- Legal: Fear of legal repercussions from participation.

- Study-Induced: Vulnerability created by the study design (e.g., deception).

- Safeguard Implementation: For each identified vulnerability, document specific mitigation strategies in the research protocol. Examples include:

Diagram: Analytical Framework for Vulnerability and Safeguards in Research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ethical Research

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Consent

| Item | Function in Ethical Research Protocol |

|---|---|

| Plain Language Guidelines | Provides rules for writing consent forms at an accessible reading level (e.g., 6th-8th grade), improving comprehension for all participants [15] [11]. |

| Readability Analysis Software | A tool (e.g., online readability calculator) to quantitatively assess and improve the readability of consent materials by analyzing character length, syllable count, and sentence structure [15]. |

| Multimedia Consent Resources | The use of videos, animations, or interactive websites to convey complex study information (e.g., data flows in digital health research), accommodating different learning preferences and literacy levels [14]. |

| Teach-Back Method Protocol | A structured communication technique where researchers ask participants to explain the study in their own words. This assesses and ensures true understanding, rather than mere signature acquisition [11] [14]. |

| Certificate of Confidentiality | A legal document issued by a public health agency (e.g., NIH in the U.S.) to protect participant privacy by shielding research data from forced disclosure in legal proceedings [16]. |

| Trained Interpreter Services | Professional interpreters (including for American Sign Language) are essential to overcome language barriers and ensure non-English speaking or hearing-impaired participants receive complete information [11]. |

The ethical enrollment of vulnerable populations in research necessitates a robust understanding of the foundational normative justifications for their protection and inclusion. The concept of vulnerability in research ethics, first formally introduced by the 1979 Belmont Report, serves as a critical mechanism to identify individuals or groups who require special protections to prevent harm and exploitation [13] [17]. Over time, scholarly and policy discourse has crystallized around three primary accounts that justify why a person is deemed vulnerable: consent-based, harm-based, and justice-based approaches [13].

These accounts are not merely theoretical; they directly inform regulatory guidelines and practical protocols for research involving human subjects. A systematic review of policy documents reveals a tendency to define vulnerability in close relation to the capacity for informed consent [13] [18]. This document synthesizes these normative justifications into structured application notes and experimental protocols, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a framework for ethically sound and methodologically rigorous research involving vulnerable populations.

Theoretical Foundations and Policy Context

The evolution of vulnerability as an independent ethical principle is reflected in major international guidelines. The Declaration of Helsinki, for instance, has significantly refined its stance on vulnerability across its revisions. The 7th revision (2013) characterizes vulnerability as an "increased likelihood of being wronged or of incurring additional harm," a definition that aligns closely with harm-based accounts [19]. The latest 8th revision further emphasizes the context-dependent and dynamic nature of vulnerability, moving beyond static group labels to focus on situational factors [19].

Contemporary thought supports a shift from a "group-based notion" of vulnerability (the "labelling approach") to an "analytical approach" [13]. The former categorizes individuals as vulnerable based on group membership (e.g., children, prisoners), while the latter focuses on identifying the potential sources and conditions that create vulnerability within a specific research context [13]. The three normative accounts provide the analytical framework for this nuanced identification process.

Table 1: Core Accounts of Vulnerability in Research Ethics

| Normative Account | Core Justification for Vulnerability | Primary Ethical Principle | Common Policy Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consent-Based | Compromised capacity to provide free, voluntary, and informed consent due to individual or situational factors [13]. | Respect for Autonomy | Requirements for surrogate decision-makers, enhanced consent processes, and assessment of decisional capacity [20] [21]. |

| Harm-Based | Increased probability of incurring physical, psychological, social, or economic harm during research [13] [19]. | Beneficence / Non-maleficence | Mandated additional safety monitoring, rigorous risk-benefit assessment, and implementation of specific protective measures [17]. |

| Justice-Based | Systemic inequalities and structural injustices that lead to unfair distribution of research burdens or exclusion from research benefits [13]. | Justice | Guidelines promoting equitable selection of participants, inclusion of underrepresented groups, and community engagement [20] [22]. |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Multi-Layered Digital Informed Consent Process

Background: The i-CONSENT guidelines recommend tailoring the informed consent process to improve comprehension and accessibility for diverse populations, including vulnerable groups [23]. This protocol outlines a method for developing and testing electronic informed consent (eIC) materials, a key tool for addressing consent-based vulnerability.

Objective: To create and validate eIC materials that achieve high comprehension and satisfaction rates among vulnerable populations, thereby mitigating consent-based vulnerabilities.

Experimental Workflow:

Methodology:

- Define Target Population: Identify the specific vulnerable population (e.g., minors, pregnant women, adults with cognitive impairments) and the study context (e.g., a vaccine clinical trial) [23].

- Co-creation and Design:

- Convene a multidisciplinary team including clinicians, ethicists, and communication experts.

- Conduct participatory design sessions (e.g., design thinking workshops) with representatives from the target population to gather input on content, format, and usability [23].

- Multi-format Development: Develop eIC materials in multiple, accessible formats to cater to different preferences and cognitive styles. Offer a combination of:

- Layered Web Content: A modular website allowing users to click for more detailed information [23].

- Narrative Videos: Use storytelling or question-and-answer formats to explain key concepts [23].

- Printable Documents: Text-based materials with integrated images and clear formatting [23].

- Customized Infographics: Visual representations of procedures, risks, and rights [23].

- Professional Translation and Cultural Adaptation: For multinational trials, translate materials professionally and adapt content to ensure cultural and contextual appropriateness [23].

- Cross-Cultural Implementation: Deploy the validated materials across different countries and settings, using a secure digital platform.

- Comprehension Assessment:

- Satisfaction Evaluation: Assess participant satisfaction using Likert scales and usability questions, with scores ≥80% considered acceptable [23].

- Data Analysis and Refinement: Use multivariable regression models to identify predictors of comprehension (e.g., gender, education, prior trial experience). Refine materials based on quantitative and qualitative feedback [23].

Key Outcomes: A study implementing this protocol with 1,757 participants across three countries demonstrated high objective comprehension (mean scores >82%) and satisfaction rates (exceeding 97%) among minors, pregnant women, and adults [23].

Protocol 2: Ethical Inclusion of Adults Lacking Decisional Capacity

Background: Adults with cognitive impairments are often excluded from clinical research due to challenges in obtaining informed consent, creating a justice-based vulnerability through underrepresentation and a lack of treatment options for their population [21]. This protocol provides a framework for their ethical inclusion.

Objective: To enroll adults who lack the capacity to provide independent informed consent into clinical trials while upholding ethical principles through robust surrogate decision-making and additional safeguards.

Ethical Enrollment Workflow:

Methodology:

- Protocol Review by IRB/REC: The research protocol must receive approval from an Institutional Review Board or Research Ethics Committee, which must verify that the inclusion of adults lacking capacity is scientifically justified and that all additional safeguards are in place [20] [17].

- Capacity Assessment: Implement a standardized and validated tool to assess the potential participant’s capacity to understand the research information and make an independent decision [21].

- Appoint a Legally Authorized Representative (LAR): If capacity is lacking, identify a surrogate decision-maker (LAR) as defined by local law and regulation to make decisions on the participant's behalf [20] [21].

- Surrogate Informed Consent Process: The investigator must provide the LAR with all relevant study information. The LAR must then provide informed consent based on their knowledge of the participant's preferences and best interests [20].

- Participant Assent: Even if formal consent is provided by the LAR, the potential participant must be included in the process to the greatest extent possible. Their willingness to participate (assent) should be sought, and any objection or sign of distress must be respected [20].

- Ongoing Monitoring and Communication: The consent process is continuous. The research team must maintain communication with both the participant and the LAR throughout the study, providing updates and reaffirming agreement, especially if the participant's condition or the study risks change [24].

- Re-consent if Capacity Returns: If the participant's decisional capacity improves, the researcher must seek direct informed consent from the participant for continued participation [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ethical Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Vulnerability and Consent Studies

| Item/Tool | Function/Brief Explanation | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Adapted QuIC Questionnaire | A validated tool to quantitatively measure objective and subjective comprehension of informed consent information [23]. | Core outcome measure in Protocol 1 to validate the efficacy of eIC materials [23]. |

| Digital Consent Platform | A secure software platform to host and deliver layered eIC materials (videos, text, infographics) and record participant engagement [23]. | Deployment vehicle for multi-format consent materials in multinational trials [23]. |

| Decisional Capacity Assessment Tool | A standardized instrument (e.g., MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research) to evaluate a person's ability to understand, appreciate, and reason about research participation [21]. | Critical for Protocol 2 to determine the need for surrogate decision-making [21]. |

| Community Advisory Board (CAB) | A group of community stakeholders and patient advocates that provides input on trial design, recruitment strategies, and consent materials to ensure cultural and ethical acceptability [20]. | Addresses justice-based vulnerability by ensuring research aligns with community needs and builds trust [20] [22]. |

| IRB/REC Vulnerability Checklist | A checklist derived from policy guidelines to systematically identify potential sources of consent-, harm-, and justice-based vulnerability in a study protocol [13] [17]. | Used by ethics committees and researchers during study design and review to ensure adequate safeguards [13]. |

The consent-based, harm-based, and justice-based accounts of vulnerability provide a complementary, rather than mutually exclusive, framework for protecting and including vulnerable populations in research. The consent-based account directly tackles the challenge of ensuring autonomy when capacity or freedom is compromised, leading to practical solutions like the eIC protocols and surrogate decision-making outlined above [13] [23] [21]. The harm-based account compels researchers and ethics committees to conduct a more nuanced risk-benefit analysis, recognizing that the same research procedure may pose a higher risk to some individuals or groups, thus necessitating additional monitoring and safeguards [13] [19]. Finally, the justice-based account critiques the historical exclusion of vulnerable groups, arguing that it perpetuates health disparities by generating evidence that does not apply to all patients [13] [20]. This justification drives policies that mandate the equitable inclusion of these populations.

A sophisticated understanding of these justifications is crucial for modern drug development professionals. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA encourage the involvement of multiple stakeholders—including patients, industry, and academia—early in clinical trial design to address these very issues [20]. The WHO's guidance on best practices for clinical trials further underscores the global imperative to "ensure ethical standards, particularly regarding informed consent, protection of vulnerable populations, and risk-benefit analysis" [22]. By systematically applying the principles and protocols described in this document, researchers can navigate the complex ethical landscape of vulnerability, advancing scientific knowledge while steadfastly upholding the rights and welfare of all research participants.

Application Note: Policy Landscape and Quantitative Synthesis

Background and Context

The ethical conduct of research with human subjects necessitates special protections for vulnerable populations to ensure equitable participation and prevent exploitation. This application note synthesizes findings from a systematic review of policy documents to elucidate how vulnerability is conceptualized, classified, and operationalized within research ethics frameworks, with particular relevance to the informed consent process [13]. The historical foundation for this discourse was established by The Belmont Report (1979), which first formally identified "vulnerable people" as those in a "dependent state and with a frequently compromised capacity to free consent" [13]. A significant challenge in this domain is balancing the imperative to protect potentially vulnerable individuals from research-related harms with the parallel need to ensure their equitable access to research benefits and participation, thereby preventing their underrepresentation in scientific advancement [13] [25].

Quantitative Synthesis of Policy Document Classifications

Analysis of 79 policy documents included in the 2025 systematic review reveals distinct patterns in the classification of vulnerable groups and the normative justifications provided for these classifications [13] [26]. The following tables synthesize the quantitative findings from this analysis, providing a structured overview for researchers and ethics committees.

Table 1: Prevalence of Vulnerable Group Classifications in Policy Documents (n=79)

| Vulnerable Population Category | Frequency of Identification | Primary Ethical Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Minors/Children | High | Inability to provide legally binding informed consent; reliance on parental permission and assent processes [27] [25]. |

| Individuals with Cognitive/Intellectual Disabilities | High | Diminished capacity to understand research participation and provide informed consent; reliance on legally authorized representatives [13] [25]. |

| Prisoners | High | Compromised free consent due to institutional dependency and potential for undue influence [13]. |

| The Very Sick or Terminally Ill | High | Potential vulnerability due to therapeutic misconception and heightened hope for benefit when no other treatment options exist [13]. |

| Economically or Educationally Disadvantaged | Medium | Potential for undue influence due to perceived financial or other benefits [13]. |

| Pregnant Women | Medium | Complexities involving the welfare of both the woman and the fetus [13]. |

| Elderly with Frailty or Dementia | Medium | Fluctuating or impaired decision-making capacity, requiring tailored consent processes like process consent [25]. |

| Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons | Emerging | Vulnerability due to legal status, language barriers, and potential trauma [25]. |

Table 2: Normative Justifications for Vulnerability in Research Ethics

| Justification Framework | Core Principle | Operational Focus in Policy Documents |

|---|---|---|

| Consent-Based Accounts | Respect for Autonomy | Focuses on a participant's compromised capacity to provide voluntary, informed, and comprehending consent due to internal (e.g., cognitive state) or external (e.g., undue influence) factors [13] [27]. |

| Harm-Based Accounts | Beneficence and Non-Maleficence | Defines vulnerability as a heightened probability of incurring harm or injury during research, necessitating enhanced risk-benefit assessments [13]. |

| Justice-Based Accounts | Justice | Identifies vulnerability as arising from systemic inequalities and social marginalization that create unfair burdens or limit access to research benefits [13]. |

Protocol for Systematic Analysis of Policy Classifications

Experimental Workflow and Methodology

The following protocol outlines a detailed methodology for systematically identifying, analyzing, and synthesizing policy document classifications of vulnerable populations, replicating and extending the approach of the foundational 2025 systematic review [13].

Figure 1: Systematic review workflow for policy analysis.

Reagent and Resource Solutions for Policy Analysis

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Systematic Policy Review

| Item/Tool | Function/Application | Specification/Example |

|---|---|---|

| PRISMA-Ethics Guideline | Provides a structured framework for conducting and reporting systematic reviews in research ethics, ensuring methodological rigor [13]. | Used to define the protocol, search strategy, and reporting standards. |

| QUAGOL Methodology | Guides the qualitative data analysis and synthesis process for policy document content, moving from summarization to conceptual scheme creation [13] [26]. | Applied during data extraction to develop summaries and identify key themes. |

| International Compilation of Human Research Standards | Serves as a primary source list for identifying relevant national and international policy documents for inclusion [13]. | 2024 Edition; ensures comprehensive coverage of global standards. |

| Structured Data Extraction Form | A standardized tool (digital or manual) for capturing consistent data points from each policy document. | Fields for: document name, year, vulnerable groups listed, definition of vulnerability, provisions, and normative justification. |

| Reference Management Software | Essential for organizing identified documents, managing citations, and facilitating the screening process. | Tools like Zotero, EndNote, or Mendeley. |

Conceptual Framework for Analytical Approaches

The systematic review identifies two predominant conceptual approaches to vulnerability that underpin policy document classifications, each with distinct implications for the informed consent process [13] [25].

Figure 2: Conceptual models for vulnerability classification.

Operational Protocol for Consent Process with Vulnerable Populations

Building on the synthesized classifications, this protocol provides actionable steps for integrating vulnerability assessments and appropriate safeguards into the informed consent process for clinical trials and research studies.

Table 4: Operational Protocol for Informed Consent with Vulnerable Populations

| Protocol Step | Detailed Procedure | Rationale & Regulatory Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-Study Vulnerability Assessment | - Identify which, if any, pre-defined vulnerable groups are likely to be enrolled.- Conduct a context-specific analysis of potential sources of vulnerability (e.g., power imbalances, economic dependency, cognitive state) [25]. | Shifts from a purely labels-based to a layers-based approach, ensuring tailored protections. Required by most international guidelines and Ethics Committee (EC) submissions [13] [25]. |

| 2. Protocol & Consent Form Development | - Justify the scientific necessity of including vulnerable participants.- Describe all specific safeguards in the research protocol.- Adapt the Informed Consent Form (ICF) language to be understandable (non-technical) and the process to be accessible [27]. | Adheres to ICH GCP E6 principles and the Declaration of Helsinki. Ensures information is comprehensible to the participant or their legal representative [27]. |

| 3. Ethics Committee Review & Approval | - Submit the full protocol, adapted ICF, and participant information materials.- Obtain explicit EC approval for the inclusion of participants who cannot give personal consent (e.g., for non-therapeutic research) [27]. | Mandatory under ICH GCP. EC must expressly approve this aspect, especially for research with no direct benefit [27]. |

| 4. Participant-Level Consent Process | For capable adults: Conduct the standard informed consent process, ensuring voluntariness and absence of undue influence.For those with limited capacity (e.g., dementia): Implement a "process consent" approach, involving ongoing consent discussions and capacity reassessment throughout the study [25].For minors: Obtain parental/legal representative permission and seek the child's assent (affirmative agreement) appropriate to their developmental stage [27] [25].For illiterate participants: Use an impartial witness during the entire informed consent discussion. The witness attests to the integrity of the process [27]. | Respects the principle of autonomy in a manner proportionate to the individual's capacity. Process consent acknowledges the fluctuating nature of capacity in some conditions. Assent respects the developing autonomy of the child [25]. |

| 5. Documentation & Monitoring | - Ensure the ICF is signed and dated by the participant or their legal representative before any trial procedures.- Provide a copy of the signed ICF to the participant/representative.- Monitor the consent process and participant well-being throughout the trial, re-consenting if new relevant information emerges [27]. | Documentary requirement per ICH GCP E6. Ongoing monitoring ensures continued willingness and upholds the ethical principle of respect for persons. |

This structured application note and protocol set provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a synthesized evidence base and actionable framework for ethically engaging vulnerable populations in research, with a specific focus on implementing a robust and tailored informed consent process.

Adapting Consent Processes: Practical Strategies for Diverse Vulnerable Groups

The process of obtaining genuine informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical research, particularly when working with vulnerable populations. Traditional consent models, often developed within Western paradigms, can be extractive and fail to account for cultural nuances, language barriers, and power dynamics. This creates a significant risk of participation without full comprehension. A shift towards culturally relevant consent is therefore not merely an ethical nicety, but a fundamental requirement for equitable and valid research. This document provides application notes and protocols for integrating these principles into research involving vulnerable populations, drawing on recent empirical studies.

Quantitative Insights: The Impact of Barriers and Interventions

Data underscores systemic deficiencies in standard consent processes for linguistically diverse and vulnerable groups, while also quantifying the benefits of targeted interventions.

Table 1: Language Barriers and Documentation of Informed Consent

| Population Group | Rate of Fully Documented Consent | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| English-Speaking Patients | 53% | 0.003 | Baseline for comparison [28] |

| Patients with Limited English Proficiency (LEP) | 28% | LEP patients were 3.1 times less likely to have fully documented consent, even with on-site interpreters available [28] |

Table 2: Efficacy of an Interpreter Access Intervention

| Metric | Pre-Intervention (LEP Patients) | Post-Intervention (LEP Patients) | English-Speaking Patients (Post) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate Informed Consent Rate | 29% | 54% | 74% |

| 30-Day Hospital Readmission Rate | 17.8% | 13.4% | Increased slightly [29] |

| Intervention | Standard interpreter access | Dual-handset interpreter phones at every bedside with 24/7 access to professional interpreters [29] | Not applicable |

Experimental Protocols for Culturally Relevant Consent

The following protocols provide actionable methodologies for designing and implementing a culturally competent consent process.

Protocol: Co-Developing Consent Materials with Communities

This protocol, based on Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Design Thinking frameworks, ensures consent processes are shaped by the communities they are intended to serve [14].

- Objective: To collaboratively create informed consent guidelines and materials that are culturally relevant, accessible, and trustworthy from the perspective of the target population.

- Materials:

- Recruitment materials co-designed with community gatekeepers.

- Venues that are neutral, accessible, and comfortable for participants.

- Audio recording equipment and secure data storage.

- Materials for participatory activities (e.g., large paper, markers).

- Procedure:

- Establish Partnerships: Identify and engage with Community Advisory Boards (CABs), local leaders, and relevant community-based organizations from the inception of the research [30].

- Participant Recruitment: Purposively sample a diverse group of stakeholders, including former research participants, CAB members, and community members representing different demographics (e.g., age, gender, nationality) and, if applicable, different language groups and literacy levels [14] [30].

- Facilitate Focus Group Discussions (FGDs): Conduct FGDs segregated by factors like age and sex to encourage open dialogue. Use open-ended questions to explore:

- Perceived motivations for and barriers to research participation.

- Experiences with and preferences for communication (oral vs. written).

- Trusted sources of information and entities.

- Understanding of core consent concepts (e.g., voluntary participation, right to withdraw).

- Specific feedback on the language and clarity of draft consent materials [14] [30].

- Iterative Material Design: Use insights from FGDs to create simplified consent forms and alternative aids (e.g., pictorial guides, audio recordings). Present these drafts back to focus groups for further feedback in a continuous cycle of refinement [14].

- Community Validation Workshops: Present the finalized guidelines and materials to a broader group of community stakeholders to confirm their acceptability and relevance [30].

- Data Analysis: Transcribe and analyze data using an inductive thematic approach to identify key barriers and facilitators [14].

The workflow for establishing an effective consent process is outlined below.

Protocol: Implementing the Consent Process with Linguistic Justice

This protocol operationalizes the co-developed materials, focusing on overcoming language and literacy barriers during the actual consent interaction.

- Objective: To ensure that every potential participant genuinely understands the research information, regardless of their language proficiency or literacy level.

- Materials:

- Finalized consent materials in all relevant languages and formats.

- Access to trained professional interpreters (in-person or via dual-handset phones). Do not use ad-hoc interpreters like family members [29].

- Audio-visual aids (e.g., short explanatory videos, diagrams).

- Procedure:

- Pre-Consent Preparation: Identify the participant's primary language and preferred mode of communication ahead of the meeting. Secure a trained interpreter who is also skilled in cultural mediation [14] [30].

- Environment Setting: Conduct the consent conversation in a private, comfortable setting. Allocate sufficient time without rushing. Introduce the interpreter and explain their role to all parties.

- Interactive Information Sharing:

- Assessing Understanding with the Teach-Back Method: After explaining a key concept (e.g., voluntary participation, risks), ask the participant to explain it back in their own words. This is not a test of the participant, but of the researcher's ability to communicate clearly. Correct any misunderstandings and re-explain as needed [14].

- Documenting the Process: For participants with LEP, document in the consent form that the discussion was conducted in their primary language with the assistance of a qualified interpreter. Include the interpreter's name and signature on the form [28].

- Reaffirming Consent: Treat consent as an ongoing process, not a one-time event. Recheck understanding and willingness to continue at key points throughout the research study [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ethical Consent

This table details key resources required to implement a culturally relevant consent process effectively.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Consent

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Community Advisory Board (CAB) | A group of community stakeholders that provides ongoing input on study design, consent materials, and recruitment strategies to ensure cultural and ethical appropriateness [30]. |

| Professional Interpreters | Trained linguists who provide accurate translation and cultural mediation. Essential for ensuring LEP participants receive identical information to English-speaking participants. Dual-handset phones provide immediate access [28] [29]. |

| Multi-Format Consent Tools | Consent information presented in various formats (e.g., short videos, pictorial flowcharts, audio recordings) to accommodate different literacy levels and learning preferences [14]. |

| Plain Language Guides | Documents that replace complex scientific and legal jargon with simple, clear terminology that is easily understood and can be accurately translated into local languages [30]. |

| Teach-Back Method Protocol | A structured method for assessing participant comprehension by asking them to explain the study back to the researcher, ensuring understanding is genuine and not assumed [14]. |

The relationships and workflow between these key tools and the desired outcomes are visualized below.

Electronic informed consent (eConsent) utilizes digital media—such as text, graphics, audio, video, and interactive websites—to convey study information and obtain consent via electronic devices [31]. A systematic review of 35 studies demonstrates that eConsent can significantly improve participant comprehension of clinical trial information, enhance engagement with content, and is rated as more acceptable and usable compared to traditional paper-based consenting [32]. For research involving vulnerable populations, eConsent offers unique opportunities to overcome barriers such as distrust, health literacy challenges, and logistical difficulties in accessing research opportunities [33] [34]. This application note provides detailed protocols and evidence-based recommendations for the effective implementation of eConsent, with a specific focus on enhancing understanding and equity in research participation.

Informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical clinical research. However, traditional paper-based consent processes present significant challenges, particularly for vulnerable and underrepresented populations. These challenges include lengthy and complex forms, difficulties in maintaining understanding, and logistical barriers to participation [33] [32].

eConsent represents a paradigm shift, moving beyond mere digitization of paper forms to a dynamic, participant-centered process. It incorporates multimedia, interactive elements, and accessibility features to make consent information more understandable and engaging [34] [35]. For vulnerable populations—including low-income individuals, racial and ethnic minorities, and those with cognitive or health challenges—eConsent can mitigate known recruitment barriers such as distrust of the research community, lack of awareness about medical research, and concerns over privacy and confidentiality [33].

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of remote and decentralized clinical trial methods, with eConsent playing a pivotal role [31] [36]. Research indicates that compared to paper-based consent, eConsent leads to a better understanding of clinical trial information, greater engagement with content, and higher ratings of acceptability and usability among participants [32]. Furthermore, fully electronic consent collection has been shown to significantly increase the initial validity of consent forms from 67.38% to 99.46%, thereby improving patient inclusion rates and data quality [37].

Quantitative Evidence: Comparative Effectiveness of eConsent

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from comparative studies and systematic reviews on the effectiveness of eConsent versus traditional paper-based methods.

Table 1: Impact of eConsent on Key Participant Outcomes [32]

| Outcome Measure | Number of Assessing Studies | Findings from "High Validity" Studies | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehension | 20 out of 35 (57%) | 6 studies reported significantly better understanding of at least some concepts with eConsent | ( P < .05 ) |

| Acceptability | 8 out of 35 (23%) | 1 study reported statistically significant higher satisfaction scores with eConsent | ( P < .05 ) |

| Usability | 5 out of 35 (14%) | 1 study reported statistically significant higher usability scores with eConsent | ( P < .05 ) |

| Cycle Time | Reported in multiple studies | Increased time spent with eConsent content, reflecting greater participant engagement | Not Significant |

Table 2: Operational and Quality Impacts of eConsent Implementation [37] [38]

| Metric | Paper-Based Consent | Tablet-Based eConsent | Context & Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial CF Validity | 67.38% | 99.46% | Based on a COVID-19 cohort study (n=2,753); higher validity reduces need for re-consenting and data loss [37]. |

| Patient Satisfaction | Baseline | 96% rated video satisfactory; 94% rated quiz satisfactory | Janssen pilot study (n=76); features enhanced understanding and engagement [38]. |

| Site Staff Feedback | Baseline | 77% reported eConsent improved the entire consent process; 69% noted improved patient engagement | Janssen pilot study; staff observed process enhancements despite variable impact on time [38]. |

| Older Adult Adaptation | N/A | High satisfaction and "easy" to "very easy" use, despite low prior tablet experience (27%) | Demonstrates acceptability across age groups and digital literacy levels [38]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Core Protocol for Remote eConsent Implementation

This protocol is adapted from successful implementations at UK Clinical Trials Units using the REDCap platform, which can be applied to studies involving vulnerable populations [31] [36].

Objective: To obtain informed consent from participants remotely using an electronic system, ensuring regulatory compliance, maintaining data integrity, and enhancing participant understanding.

Materials:

- REDCap Software Platform: A secure, web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases. No-cost options are available for academic research [36].

- Communication Tools: Telephone or video conferencing software for initial discussion and identity verification.

- Device with Internet Access: For the participant to access the eConsent system.

Procedure:

- Pre-Consent Discussion and Information Provision:

- A researcher introduces the study to the potential participant via phone or video call.

- The researcher explains the option of eConsent and confirms the participant's interest and access to a suitable device.

- The Participant Information Sheet (PIS) is sent to the participant electronically (e.g., via email) or by post, allowing time for review.

Verbal Consent for Data Processing:

- Before any confidential information is entered into the eConsent system, the researcher obtains verbal consent from the participant for the processing of their personal data as required by data protection regulations (e.g., GDPR) [36].

Identity Verification:

- The researcher verifies the participant's identity. This can be done visually on a video call, by checking basic identifiers (name, date of birth), or in-person at a subsequent visit before any study intervention is administered [36].

System Access and Electronic Consent:

- The researcher sends a unique link to the REDCap eConsent form via email.

- The participant opens the link and reviews the electronic Consent Form (eICF), which may include embedded multimedia (videos, audio clips) and interactive knowledge checks.

- The participant provides their electronic signature. Per regulatory guidance, this can be a simple electronic signature (e.g., a typed name) for many research contexts, provided it is unique to the signer and linked to the record [39].

Documentation and Copy Provision:

- The completed eICF is locked in the system, generating an audit trail.

- A copy of the signed eICF is automatically emailed to the participant for their records.

Workflow Diagram: Remote eConsent Process

The diagram below illustrates the sequential and parallel steps in a standardized remote eConsent process, highlighting the roles of both research staff and participants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for eConsent

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for eConsent Implementation

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose in eConsent | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| eConsent Platform | Core software for creating, delivering, and managing electronic consent forms. | REDCap: A widely used, secure, no-cost platform for academic research with a built-in eConsent module [31] [36]. Commercial platforms also exist. |

| Multimedia Components | To enhance comprehension and engagement by presenting information in multiple formats. | Instructional Videos: Explain key study concepts [38]. Interactive Diagrams: Illustrate study design. Audio Narration: Supports low literacy. |

| Interactive Comprehension Checks | To assess and reinforce participant understanding of key study elements during the consent process. | Embedded Quizzes: Multiple-choice questions on risks, procedures, and rights [38]. Feedback is provided for incorrect answers. |

| Electronic Signature Solution | To capture a legally valid signature electronically. | Platforms like DocuSign or built-in tools in REDCap. Must meet regulatory requirements for intent and attribution [39]. |

| Accessibility Features | To ensure the eConsent process is inclusive for participants with diverse abilities and language preferences. | Screen Reader Compatibility, Variable Font Sizes, Multiple Language Options [34] [36]. |

| Identity Verification Protocol | To confirm the identity of the participant providing remote consent, as per regulator guidance [36]. | Process may involve video call confirmation, checking government-issued ID, or asking security questions (e.g., mother's maiden name) [39] [36]. |

Adaptation for Vulnerable Populations: Tailoring the Protocol

A one-size-fits-all approach is insufficient for vulnerable groups. Tailoring the eConsent process is critical for ethical and effective implementation.