Ethical Research with Vulnerable Populations: Balancing Protection, Participation, and Progress

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the ethical engagement of vulnerable populations in clinical research.

Ethical Research with Vulnerable Populations: Balancing Protection, Participation, and Progress

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the ethical engagement of vulnerable populations in clinical research. It explores the foundational ethical principles and historical context that shape current guidelines, offers methodological frameworks for obtaining genuine informed consent and building trust, addresses common challenges like dual-role conflicts and study termination ethics, and validates approaches against contemporary issues such as globalization and digital health. The content synthesizes the latest systematic reviews and case studies to deliver actionable strategies for conducting rigorous, ethical, and inclusive research.

From Belmont to Today: Defining Vulnerability and Learning from History

The ethical conduct of research is foundational to the integrity of the scientific enterprise and the protection of society. Historical abuses of human subjects, such as those uncovered in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Nazi medical experimentation, highlighted the critical need for a formalized ethical framework [1]. In response, the 1978 Belmont Report established three core principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—which form the cornerstone of modern research ethics regulations and practice [1]. These principles provide a systematic framework for analyzing ethical issues and guiding researcher conduct.

Within the context of a broader thesis on vulnerable populations in research ethics, these principles take on heightened significance. Vulnerability in research is defined as "an identifiably increased likelihood of incurring additional or greater wrongs" due to participation [2]. The Belmont Report itself notes that "persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection," directly linking the ethical principles to the protection of vulnerable subjects [3]. This guide explores the application of these principles specifically within the context of research involving vulnerable populations, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with both the theoretical understanding and practical tools necessary for ethical research conduct.

The Principle of Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two fundamental ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [1]. An autonomous person is "an individual capable of deliberation about personal goals and acting under the direction of such deliberation" [1]. This principle manifests primarily through the requirements for informed consent and additional protections for vulnerable populations.

Informed Consent in Practice

Informed consent is not merely a form to be signed, but rather an ongoing process of communication that ensures a potential subject understands the research and voluntarily agrees to participate [4]. The Belmont Report outlines the key elements necessary for valid informed consent:

- Information: Prospective subjects must be provided with all material information about the research, including its purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives [1].

- Comprehension: The information must be presented in a manner and language that the subject can understand, acknowledging varying capacities for comprehension [1].

- Voluntariness: Agreement to participate must be given without coercion or undue influence, ensuring the decision is free and autonomous [1].

Application to Vulnerable Populations

Vulnerable populations often face challenges that compromise their ability to provide fully autonomous informed consent. Two dominant approaches to understanding vulnerability have emerged in research ethics: the categorical approach and the contextual approach [3].

Table 1: Approaches to Vulnerability in Research Ethics

| Approach | Description | Examples of Vulnerable Groups | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical Approach | Considers certain groups or populations as inherently vulnerable [3]. | Children, prisoners, pregnant women, economically disadvantaged persons, persons with cognitive impairments [3] [1]. | Does not address persons with multiple vulnerabilities or variation within groups; may over-generalize [3]. |

| Contextual Approach | Identifies situations and contexts that render individuals vulnerable [3]. | A capable CEO experiencing chest pain in an ER; a non-native language speaker; a patient in a deferential doctor-patient relationship [3]. | Requires more nuanced assessment by researchers and IRBs; less prescriptive [3] [5]. |

For individuals with compromised capacity, such as those with dementia or cognitive impairments, the consent process requires special adaptations. Process consent is a method in which consent is viewed as ongoing rather than a one-time event, with continuous checks for understanding and willingness to continue [6]. When prospective participants lack capacity, researchers must identify a legally authorized representative (surrogate) to give permission for enrollment, while still finding ways to involve the person with diminished capacity in decision-making to the greatest extent possible [2] [6].

The Principle of Beneficence

The principle of Beneficence entails an obligation to act for the benefit of others by minimizing possible harms and maximizing potential benefits [1]. This principle goes beyond simply "do no harm" (nonmaleficence) to include actively promoting the welfare of research participants [7]. For vulnerable populations, this principle requires a careful and systematic assessment of risks and benefits.

Risk-Benefit Assessment

A favorable risk-benefit ratio is a cornerstone of ethical research [4]. Researchers must meticulously analyze potential risks, which can be physical, psychological, social, or economic, and work to minimize them [4] [1]. Simultaneously, potential benefits to the participant and to society must be identified. The doctrine of double effect is relevant here, where an action with a foreseen but unintended harmful effect (e.g., opioid sedation for pain relief) may be ethically permissible if the intended action is beneficial [7].

Table 2: Risk-Benefit Assessment Framework for Vulnerable Populations

| Assessment Component | Key Considerations for Vulnerable Populations | Protective Safeguards |

|---|---|---|

| Nature & Scope of Risks | Vulnerable groups may be at higher risk for certain physical, psychological, or social harms [5]. Risks must be contextual, not just categorical [3]. | Implement additional monitoring; consult with community representatives; use staged consent processes [3]. |

| Potential Benefits | Ensure benefits are not overstated ("therapeutic misconception"); consider whether the vulnerable group will have access to proven benefits [4]. | Clear communication of uncertainties; post-trial access plans; alignment of research with health needs of the community [4] [8]. |

| Risk Minimization | Requires special consideration of the vulnerable group's specific circumstances and capacities [2]. | Use of plain language; independent participant advocates; data safety monitoring boards [3] [4]. |

Methodological Considerations

The principle of beneficence also demands scientific validity [4]. A study must be designed in a way that will yield reliable and actionable results. It is unethical to expose participants, especially vulnerable ones, to any risk in a study that is so poorly designed that it cannot answer the research question [4]. This requires careful attention to study design, sample size, and statistical analysis to ensure the research is valid and feasible.

The Principle of Justice

The principle of Justice addresses the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [1]. Historically, the burdens of research often fell disproportionately on vulnerable populations, while the benefits flowed primarily to more privileged groups [1]. This principle demands a careful examination of the selection of research subjects.

Fair Subject Selection

The primary basis for recruiting participants should be the scientific goals of the study—not vulnerability, privilege, or ease of availability [4]. Fair subject selection requires that:

- Populations that are likely to benefit from the research should not be excluded without a compelling scientific reason [4].

- Groups should not be targeted for research simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or manipulability [1].

- There should be a fair distribution of the burdens of research across different societal groups, avoiding the systematic selection of any group due to their vulnerability [1].

Vulnerability and Justice

The link between justice and vulnerability is profound. A justice-based account of vulnerability points to unequal conditions and/or opportunities for research subjects as a source of vulnerability [5]. The systematic exclusion of vulnerable groups from research can also be a violation of justice, as it may prevent these populations from benefiting from the knowledge gained through research [5] [2]. The goal is to avoid both the underprotection of vulnerable groups (by exploiting them in research) and their overprotection (by systematically excluding them, thus limiting the generalizability of research findings and their access to potential benefits) [5].

Experimental Protocols and Ethical Safeguards

Institutional Review and Oversight

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) is a primary mechanism for ensuring ethical research conduct. IRBs provide independent review of research proposals to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects [4] [1]. When research involves vulnerable populations, the IRB's role is particularly critical. Researchers must provide the IRB with a detailed plan outlining how they will address the specific vulnerabilities of the participant population, including adequate safeguards and a robust informed consent process [3] [1].

Recent updates to federal regulations, such as the 2024 Public Health Service (PHS) Policies on Research Misconduct, emphasize the importance of institutional responsibilities in maintaining research integrity, including clearer requirements for investigations and extended timelines for inquiries [9]. These regulatory frameworks provide the structure for holding researchers accountable.

Protocol for Research with Cognitively Vulnerable Populations

Research Question: What is the experience of care among individuals living with early-stage dementia?

Ethical Justification: Including persons with dementia in research that affects their treatment and care is essential for developing person-centered interventions. Exclusion challenges ethical practice by silencing their voices [6].

Methodology & Ethical Safeguards:

- Capacity Assessment: Implement a structured, objective capacity assessment prior to enrollment, using tools validated for research consent in dementia [2].

- Process Consent: Adopt a "process consent" model, where consent is reaffirmed throughout the research journey. Before each data collection session, briefly re-explain the study and confirm continued assent [6].

- Surrogate Consent: For participants who lack capacity to provide independent informed consent, obtain permission from a legally authorized representative [2] [6].

- Assent and Dissent: Even when surrogate consent is obtained, respect the participant's ongoing expression of assent (willingness) or dissent (withdrawal). Any sign of distress or opposition should be honored immediately [6].

- Caregiver Involvement: Enroll primary caregivers with their own informed consent, as they may be more involved as the participant's cognitive impairment worsens [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Ethical Research

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Practice

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Ethical Research |

|---|---|

| Validated Capacity Assessment Tools | Provides an objective measure of a potential participant's understanding and decision-making capacity, crucial for research with cognitively impaired populations [2]. |

| Plain-Language Consent Templates | Facilitates true comprehension by presenting information in clear, accessible language, avoiding technical jargon. May require cultural adaptation and translation [3] [4]. |

| Independent Participant Advocate | A third party, unaffiliated with the research team, who can help the participant understand their rights and ensure participation is voluntary, particularly important for institutional or deferential vulnerability [3]. |

| Data Anonymization & Encryption Software | Protects participant confidentiality and privacy, a key aspect of Respect for Persons and Beneficence, by securing data and removing identifiable information [1]. |

| Cultural & Linguistic Consultation Services | Ensures research materials and the consent process are respectful and comprehensible across language and cultural barriers, addressing communicative vulnerability [3] [10]. |

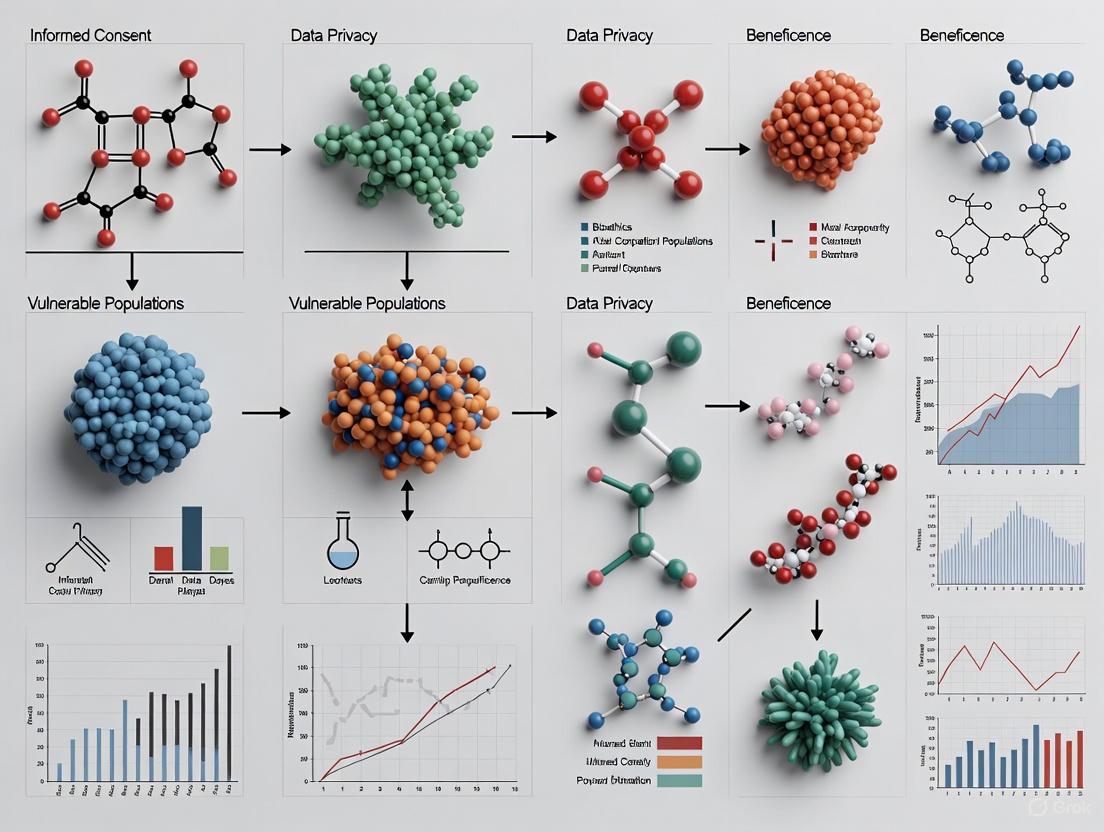

Visualizing the Ethical Framework

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core ethical principles, their practical applications, and the overarching goal of protecting vulnerable populations in research.

The core ethical principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice provide an indispensable framework for conducting research with vulnerable populations. Moving beyond a rigid, categorical view of vulnerability to a more nuanced, contextual understanding allows researchers to identify specific sources of vulnerability and implement proportionate safeguards. This involves robust informed consent processes, meticulous risk-benefit analyses, and a steadfast commitment to fair subject selection. As the research landscape evolves, with new challenges such as those highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic and addressed by frameworks like the PREPARED Code [8], the continued application of these principles ensures that the pursuit of scientific knowledge remains firmly grounded in the protection of human dignity, rights, and welfare. For researchers, this is not merely a regulatory obligation but a fundamental professional responsibility.

The history of clinical research is marked by profound ethical failures that have irrevocably shaped modern regulatory frameworks. The examination of three pivotal cases—the Nazi medical experiments, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and the Willowbrook hepatitis studies—reveals a consistent pattern of exploitation where autonomous decision-making was systematically denied to vulnerable populations. These historical violations directly catalyzed the development of foundational ethical documents, beginning with the Nuremberg Code in 1947, which established the non-negotiable requirement for voluntary informed consent [11] [12]. The legacy of these abuses extends beyond the creation of rules; it instilled a fundamental principle that continues to guide research ethics: the protection of vulnerable populations is paramount to conducting morally justifiable research.

This whitepaper analyzes these historical cases through the lens of vulnerability, examining how systemic power imbalances and compromised consent capacities led to egregious harms. Furthermore, it traces the evolution of ethical thought from the Nuremberg Code through the Belmont Report to contemporary guidelines, which have progressively refined the concept of vulnerability from a simple categorical approach to a more nuanced analytical framework [5] [13]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this history and its enduring legacy is not an academic exercise but a professional imperative. It provides the essential context for the rigorous ethical standards and oversight mechanisms that underpin legitimate clinical research today [12].

Historical Case Studies: Analysis of Ethical Violations

The following cases represent critical benchmarks in the history of research ethics. Each exemplifies unique ethical failures and collectively highlighted the urgent need for formal protections for human participants.

The Nuremberg Code (1947)

Background and Context: The Nuremberg Code was formulated in 1948 in direct response to the atrocities committed by Nazi physicians during World War II [14] [11]. An American military war crimes tribunal prosecuted 23 Nazi physicians and administrators for conducting lethal and traumatic medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners without their consent [11]. These experiments included exposure to extreme temperatures, low air pressures, ionizing radiation, and infectious diseases, as well as wound-healing and surgical studies, including vivisections [14]. The judicial condemnation of these acts resulted in the codification of ten standards for physicians to follow when carrying out experiments on human participants.

Ethical Violations and Core Principles: The Nazi experiments constituted the most fundamental violations of ethical principles. They were characterized by a complete absence of voluntary consent, the infliction of extreme harm and suffering, and the use of a coerced and captive population [14] [12]. The experiments were designed not for the benefit of the participants, but for state interests, such as advancing military medicine. In the subsequent "Doctors' Trial," the defendants argued that no international law differentiated between legal and illegal human experimentation, highlighting a critical regulatory gap [15].

The resulting Nuremberg Code established ten standards, with the first and foremost principle being voluntary consent, which it describes as "absolutely essential" [11]. Other key standards include the right of a participant to withdraw, the requirement that experiments should yield fruitful results for the good of society, and the principle that a study should never be conducted if there is reason to believe death or disabling injury may occur [11]. It placed the responsibility for ensuring ethical conduct squarely on the researcher.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1972)

Background and Context: The U.S. Public Health Service conducted a 40-year observational study titled the "Untreated Syphilis Study in the Negro Male" in Tuskegee, Alabama [16]. The study aimed to document the natural progression of syphilis in 400 African American men who had the disease, alongside a control group of 201 men without it [16] [11]. The participants were primarily poor, rural sharecroppers who were offered incentives such as free medical examinations, free meals, and burial insurance [11]. Crucially, they were not informed of their diagnosis; researchers told them they were being treated for "bad blood" [16] [11].

Ethical Violations and Core Principles: The Tuskegee study is a landmark case of pervasive ethical failure rooted in injustice and deception.

- Lack of Informed Consent: Researchers never collected informed consent from participants and deliberately withheld information about their disease [16].

- Withholding of Treatment: The most egregious violation was the deliberate denial of treatment. Even after penicillin became the standard, effective treatment for syphilis in the 1940s, researchers actively prevented participants from accessing it [16] [11] [12].

- Injustice and Vulnerability: The study targeted a socially and economically vulnerable population—disadvantaged African American men [11]. The risks and burdens of the research were placed entirely on this group, while the potential benefits of understanding the disease were for society at large, a clear violation of the principle of justice [11].

- The study ended in 1972 only after a news story alerted the public and Congress to its ethical problems [14] [16]. A subsequent advisory panel concluded the study was ethically unjustified. In 1997, President Bill Clinton issued a formal presidential apology on behalf of the U.S. government [16] [11].

The Willowbrook Hepatitis Study (1956-1970)

Background and Context: From 1956 to 1970, researchers conducted studies at the Willowbrook State School, a New York institution for "mentally handicapped" children [11] [12]. The research aimed to study the course of viral hepatitis and the effectiveness of an immunoglobulin for inoculating against it [11]. Willowbrook was severely overcrowded, housing over 6,000 residents in a facility designed for 4,000, and conditions were deplorable, with insufficient food, attendants, or sanitation [17].

Ethical Violations and Core Principles: The ethical breaches at Willowbrook involved the exploitation of a highly vulnerable population and a coercive consent process.

- Intentional Infection of Children: Researchers deliberately infected children with the hepatitis virus [11]. They administered the virus to newly admitted children, often disguised within a "vaccination" protocol [11].

- Coerced Parental Consent: While some form of consent was obtained from parents, the context was highly coercive. The school was overcrowded, and there is evidence that the institution only admitted children whose parents gave permission for them to be in the study, holding admission hostage to recruitment [17] [11] [12]. This represents a profound undue influence.

- Exploitation of the Vulnerable: The participants were children with intellectual disabilities, a group with diminished autonomy and a high degree of vulnerability. They were institutionalized and could not advocate for themselves, making them easy subjects for exploitation [12].

- Public Exposure and Legacy: The horrific conditions at Willowbrook were exposed to the public in 1972 by journalist Geraldo Rivera, whose footage showed children "rotting" in their own waste [17]. This exposé fueled public outrage and a class-action lawsuit, which culminated in a 1975 consent decree mandating improved conditions and the deinstitutionalization of residents [17].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Ethical Violations in Human Subjects Research

| Case Study | Dates | Vulnerable Population | Key Ethical Violations | Primary Ethical Principle Violated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nazi Experiments | 1939-1945 | Concentration camp prisoners [14] | - Non-consensual, fatal experiments- Intentional infliction of harm [12] | Respect for Persons, Beneficence |

| Tuskegee Syphilis Study | 1932-1972 | African American men [16] | - Lack of informed consent- Withholding of known treatment (penicillin) [16] [11] | Justice, Respect for Persons |

| Willowbrook Hepatitis Study | 1956-1970 | Children with intellectual disabilities [11] [12] | - Intentional infection with pathogen- Coerced parental consent [11] | Respect for Persons, Beneficence |

The Evolution of Ethical Protections and Conceptualizing Vulnerability

The historical violations detailed above served as catalysts for the development of increasingly sophisticated ethical frameworks and regulations designed to protect human research participants.

From Nuremberg to Belmont: A Timeline of Ethical Guidance

The progression of ethical thought can be traced through several key documents that built upon the lessons of past abuses:

- The Nuremberg Code (1947): Established the absolute necessity of voluntary consent and laid down nine other standards for ethical research, shifting responsibility to the investigator [11].

- The Declaration of Helsinki (1964): Adopted by the World Medical Association, this declaration addressed research on patient populations and explicitly stated that the interests of the individual patient must take precedence over the interests of society [11]. It has been revised multiple times to address emerging ethical challenges.

- The Belmont Report (1979): This seminal report, created in direct response to the Tuskegee scandal, identified three core ethical principles that should guide research involving human subjects [5] [11]:

- Respect for Persons: Recognizing the autonomy of individuals and protecting those with diminished autonomy. This principle is operationalized through the process of informed consent.

- Beneficence: The obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms. This is applied through a systematic assessment of risks and benefits.

- Justice: The requirement to ensure the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research. This addresses the selection of subjects to avoid exploiting vulnerable populations [11].

The following diagram illustrates the causal relationship between historical abuses and the development of these major ethical codes:

Conceptualizing Vulnerability in Research Ethics

The notion of vulnerability was formally introduced into research ethics through The Belmont Report, which defined vulnerable people as those in a "dependent state and with a frequently compromised capacity for free consent," citing examples such as racial minorities, the very sick, and the institutionalized [5] [13]. Since then, policy documents and guidelines have struggled to operationalize this concept. A systematic review of research ethics policy documents reveals two primary approaches to conceptualizing vulnerability [5] [13]:

The Group-Based (or Categorical) Approach: This traditional approach identifies specific groups as inherently vulnerable. Common categories include children, prisoners, pregnant women, individuals with intellectual or mental disabilities, and economically or educationally disadvantaged persons [5]. This approach is pragmatically simple for ethics committees but can be over-inclusive and stigmatizing.

The Analytical Approach: This more recent and nuanced approach focuses on the potential sources or contexts that create vulnerability, rather than predefined groups. It includes three main accounts:

- Consent-based accounts: Vulnerability stems from a compromised capacity to provide voluntary, informed consent due to undue influence, coercion, or reduced autonomy.

- Harm-based accounts: Vulnerability is defined as a higher probability of incurring harm or exploitation during research.

- Justice-based accounts: Vulnerability arises from systemic, social, or economic inequalities that lead to unfair distribution of research burdens and benefits [5] [13].

Table 2: Analytical Framework for Sources of Vulnerability in Research

| Source of Vulnerability | Definition | Historical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Consent-Based | Compromised capacity for autonomous, informed decision-making due to coercion, undue influence, or diminished mental capacity. | Willowbrook parents coerced into consenting for their child's admission [17] [11]. |

| Harm-Based | Increased susceptibility to physical, psychological, social, or economic harm as a result of research participation. | Nazi experiment subjects and Tuskegee participants who suffered death and disability [14] [12]. |

| Justice-Based | Systemic inequities leading to the unfair selection of and burden placed on particular populations. | Selection of exclusively African American men for the Tuskegee study [16] [11]. |

The following diagram maps the relationship between historical cases, the vulnerable groups involved, and the primary sources of their vulnerability:

The Modern Legacy: Applications and Contemporary Challenges

The legacy of historical violations is deeply embedded in the everyday practice of clinical research, from protocol design to regulatory oversight. The ethical frameworks born from past failures provide guidance for navigating modern complexities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for Ethical Research

The following table details key components derived from ethical guidelines that are now non-negotiable for conducting research with human participants.

Table 3: Essential Components for Ethical Clinical Research

| Component | Function in Upholding Ethics | Originating Principle/Document |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent Form | Documents the process of providing full information and obtaining voluntary, comprehending agreement from a participant. | Nuremberg Code [11], Respect for Persons (Belmont) [11] |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee | An independent committee that reviews research protocols to ensure ethical soundness and the protection of participants' rights and welfare. | Declaration of Helsinki [12], The Belmont Report [12] |

| Protocol-Benefit/Risk Analysis | A systematic assessment within the research protocol to justify the risks posed to participants by the potential benefits of the knowledge gained. | Beneficence (Belmont) [11], Declaration of Helsinki [11] |

| Vulnerability Assessment | A proactive evaluation to identify potential sources of vulnerability among the proposed participant population and to outline additional safeguards. | The Belmont Report [11], CIOMS/ICH-GCP Guidelines [5] |

| Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) | An independent group of experts that monitors participant safety and treatment efficacy data while a clinical trial is ongoing. | Beneficence (Belmont), post-Tuskegee regulatory refinement [12] |

Contemporary Ethical Challenges

While modern regulations are robust, new ethical challenges continuously emerge, requiring researchers to apply foundational principles in novel contexts [12]:

- Globalization of Clinical Trials: Conducting research in low- and middle-income countries raises concerns about informed consent in different cultural contexts, the standard of care provided to control groups, and the potential for exploitation of economically disadvantaged populations [12]. The principle of justice demands that host communities have access to the fruits of the research.

- Inclusion vs. Protection of Vulnerable Populations: There is a necessary tension between protecting vulnerable groups from potential harm and ensuring their equitable representation in research. Over-protection can lead to a lack of data on how treatments work in these populations, perpetuating health inequities [5] [12]. The modern trend is toward carefully managed inclusion with additional safeguards, rather than blanket exclusion.

- Emerging Technologies: The use of artificial intelligence, genomic data, and digital health tools poses new challenges regarding informed consent for data re-use, data privacy, and algorithmic fairness [12]. These technologies can also create new vulnerable groups, such as those marginalized by algorithmic bias.

The historical violations of Tuskegee, Willowbrook, and the Nazi era are not merely dark chapters in a closed book. They are living history whose lessons are codified in the very fabric of modern clinical research ethics. These cases unequivocally demonstrate that without rigorous ethical frameworks and constant vigilance, scientific curiosity can override human dignity, particularly for the most vulnerable among us.

The evolution from the Nuremberg Code to the analytical approach to vulnerability represents a maturation of ethical thought—from a reactive set of rules to a proactive, principle-based system. For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this legacy imposes a solemn responsibility. It is not enough to simply comply with regulations. True ethical conduct requires a deep-seated commitment to the principles of respect, beneficence, and justice, and a critical self-awareness that acknowledges the potential for vulnerability in all research contexts. By embedding these principles into every stage of research—from design and recruitment to publication and post-trial access—the scientific community can honor the victims of past abuses by ensuring that their legacy is the unwavering protection of every human participant.

What Makes a Population Vulnerable? Moving Beyond Labels to an Analytical Approach

The protection of vulnerable populations is a cornerstone of modern research ethics, yet the operationalization of this concept often relies on outdated categorical models. Historically, guidelines have used a "labeling approach," identifying vulnerability based solely on an individual's membership in a predefined group, such as children, prisoners, or the economically disadvantaged [13]. This method, while pragmatically simple for research ethics committees, risks being both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. It may fail to identify vulnerable individuals outside standard categories while also applying unnecessary protections to group members not actually experiencing vulnerability in a specific research context [13] [5].

Contemporary ethical discourse now champions a shift toward an "analytical approach" that focuses on the specific sources and contexts that create vulnerability [13] [5]. This framework moves beyond mere categorization to diagnose the underlying conditions that compromise free and informed consent, increase risk of harm, or perpetuate injustice. This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the conceptual tools and practical methodologies to implement this analytical approach, ensuring both ethical rigor and equitable participation in research.

Core Analytical Frameworks: Deconstructing Vulnerability

The analytical approach to vulnerability dissects the concept into three primary normative accounts, each focusing on a distinct source of compromised ethical standing in research settings. The following diagram illustrates the structure of this analytical framework.

Consent-Based Accounts

This framework locates vulnerability primarily in impairments to the capacity for providing free and informed consent [13] [5]. Vulnerability arises when potential participants have a compromised ability to understand the research, appreciate its consequences, or voluntarily decide without undue influence. This can stem from intrinsic factors (e.g., cognitive impairments, developmental stage) or extrinsic factors (e.g., coercive pressures in hierarchical relationships) [18]. For instance, a prisoner's consent may be considered vulnerable not merely due to their status as an inmate, but because the institutional context creates a potential for coercion or undue inducement that must be specifically assessed and mitigated [13].

Harm-Based Accounts

This perspective defines vulnerability in relation to a heightened probability of incurring physical, psychological, social, or economic harm during research [13] [5]. The focus is on the participant's relative inability to absorb or recover from research-related risks. For example, a patient with a terminal illness may be vulnerable not simply because of their diagnosis, but because their compromised physical state makes them more susceptible to the side effects of an experimental therapy or less able to cope with additional burdens. This account requires a contextual analysis of the specific research interventions in relation to the participant's resilience and resources [18].

Justice-Based Accounts

Justice-based accounts point to unequal conditions and opportunities as the source of vulnerability [13] [5]. This framework emphasizes distributive justice, focusing on populations that have been historically underrepresented in research or unfairly burdened by it. Vulnerability arises from systemic factors that limit access to the benefits of research participation or disproportionately expose groups to risks. This includes populations experiencing health disparities due to social determinants of health, such as poverty, discrimination, or lack of access to care [19]. The core ethical imperative here is to ensure fair inclusion and address health inequities through research.

Operationalizing the Analytical Framework: Assessment and Application

The table below translates traditional vulnerable population categories into their potential vulnerability sources according to the analytical framework, demonstrating that single groups often face multiple, overlapping sources of vulnerability that require distinct safeguards.

Table 1: Analytical Mapping of Traditionally Vulnerable Populations

| Population Category | Primary Vulnerability Sources | Contextual Factors Modifying Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Children & Minors [18] | Consent-Based (developing decision-making capacity) [13] | Age, maturity, psychological state, family dynamics [18] |

| Pregnant Women [18] | Harm-Based (risk to fetus and mother) [18] | Stage of pregnancy, availability of pre-clinical toxicity data [18] |

| Prisoners [13] | Consent-Based (institutional coercion) [13] | Prison conditions, nature of the research, potential for parole |

| Economically/Educationally Disadvantaged [13] | Justice-Based (unfair access) & Consent-Based (undue inducement) [13] [5] | Level of disadvantage, social context, research topic |

| Cognitively Impaired [18] | Consent-Based (impaired comprehension/capacity) [13] [18] | Fluctuation in capacity, availability of LARs, study complexity [18] |

| Terminally Ill [18] | Harm-Based (increased susceptibility) & Consent-Based (therapeutic misconception) [13] | Prognosis, availability of standard treatment, level of pain/distress |

Methodologies for Contextual Vulnerability Assessment

Implementing the analytical approach requires structured methodologies to replace categorical checklists.

Systematic Review Protocol for Policy Analysis: A rigorous methodology for analyzing how vulnerability is conceptualized involves systematic reviews of policy documents following PRISMA-Ethics guidance [13] [5]. The process includes:

- Search Strategy: Comprehensive searching of policy sources (e.g., International Compilation of Human Research Standards), databases (PubMed, Web of Science), and grey literature (Google Scholar) using structured search strings [5].

- Screening & Data Extraction: Independent screening of documents against eligibility criteria, followed by extraction of data pertaining to definitions, listed populations, justifications, and provisions [13] [5].

- Qualitative Analysis: Using frameworks like the QUAGOL methodology to analyze and synthesize findings, identifying recurring patterns and conceptual gaps in policy guidance [5].

Staged Review Process for Research Ethics Committees (RECs): A practical protocol for RECs and researchers to apply the analytical approach involves:

- Protocol-Driven Identification: Requiring researchers to justify not only if vulnerable populations are included, but to analyze why they might be vulnerable in the specific study context.

- Source-Specific Safeguard Matching: Mandating that proposed safeguards (e.g., independent consent monitors, data safety monitoring boards) are directly linked to the identified sources of vulnerability (consent, harm, justice) rather than applying generic protections [18] [19].

- Ongoing Monitoring: Implementing continued ethics review to assess if vulnerability profiles change during the research, requiring re-consent or additional safeguards [18].

Effectively engaging with vulnerable populations requires specialized tools and resources to translate ethical principles into practice.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Vulnerable Populations Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bilingual Research Assistants [19] | Overcome language barriers; ensure accurate translation of consent materials and data collection; build trust with non-English speaking participants. | Recruiting and conducting informed consent and interviews with Spanish-speaking participants in their native language [19]. |

| Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) Protocols [18] | Provide a structured mechanism for obtaining informed consent on behalf of potential participants who lack decision-making capacity. | Outlining in the study protocol the conditions for seeking surrogate consent for individuals with fluctuating cognitive impairment [18]. |

| Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) [18] | Provide independent oversight of study data and participant safety, particularly crucial when risks are uncertain or participants have diminished resilience. | A DSMB conducts interim analyses to recommend trial continuation, modification, or termination based on emerging benefit-risk data for a vulnerable group [18]. |

| Trauma-Informed Interview Guides [19] | Semi-structured guides developed with clinical expertise (e.g., from Licensed Clinical Social Workers) to minimize re-traumatization during data collection. | An LCSW reviews and refines an interview guide for survivors of violence to ensure questions are phrased sensitively and avoid psychological harm [19]. |

| Community Advisory Board (CAB) [19] | Integrate community perspectives into research design and conduct; ensure cultural appropriateness; build mutual trust and respect. | A CAB comprising community members provides feedback on recruitment strategies and consent form readability for a study involving homeless individuals [19]. |

The movement from a label-based to an analytical approach in identifying vulnerable populations represents a critical evolution in research ethics. This framework provides researchers and ethics committees with a more precise, contextual, and ethically robust methodology for safeguarding participant rights and well-being. By systematically analyzing the sources of vulnerability—whether rooted in consent, harm, or justice—and deploying tailored safeguards, the research community can better fulfill its dual imperative: to protect participants from harm while ensuring their equitable inclusion in the benefits of scientific research. This nuanced practice is fundamental to conducting ethically sound and socially responsible science.

Within research ethics, vulnerability serves as a crucial regulatory category, signaling to researchers and ethics committees that some participants may be at an increased risk of harm or wrong [20]. Since its formal introduction in the 1979 Belmont Report, the concept has been central to safeguarding participants, yet its conceptualization and application have been subjects of ongoing debate [5] [21] [20]. A significant advancement in this discourse is the emergence of an analytical approach to vulnerability, which moves beyond merely listing vulnerable groups to examining the underlying sources and contexts that create vulnerability [5] [21]. This approach is structured around three primary normative justifications: consent-based, harm-based, and justice-based accounts [5]. Understanding these distinct yet sometimes overlapping justifications is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to design and conduct ethically sound research that adequately protects all participants.

Theoretical Foundations of the Three Accounts

The analytical approach to vulnerability seeks to identify the specific conditions and sources that render a potential research participant vulnerable. The following table summarizes the core principles, sources, and implications of the three primary accounts.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Normative Justifications for Vulnerability

| Account of Vulnerability | Core Ethical Principle | Source of Vulnerability | Key Question for Researchers | Protective Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent-Based | Respect for Persons / Autonomy [5] [20] | Compromised capacity for autonomous decision-making and informed consent due to cognitive impairment, undue influence, or coercion [5] [21]. | Is the participant's consent truly informed, comprehended, and free from coercion? [10] | Use of surrogate decision-makers, enhanced consent processes, independent consent monitors, continuous assessment of willingness to participate [5] [22]. |

| Harm-Based | Beneficence / Non-maleficence [20] | Increased likelihood of incurring additional or greater physical, psychological, social, or economic harm [13] [21] [20]. | What are the specific risks to this participant, and are they greater than those faced by a "standard" participant? | Robust risk-benefit analysis, protocol modifications to minimize risks, close monitoring, provision of counseling and medical support, clear plans for managing adverse events. |

| Justice-Based | Justice / Equity [5] [20] | Systemic, social, or economic inequalities that lead to unfair distribution of research burdens or exclusion from research benefits [5] [21]. | Is the recruitment fair, and will the research perpetuate or alleviate existing health disparities? [21] | Fair selection of participants, inclusive recruitment strategies, community engagement, ensuring research addresses the needs of the group, post-trial access to benefits. |

The Evolution from Group-Based to Analytical Approaches

Historically, research ethics guidelines employed a "group-based" or "labelling" approach, identifying vulnerability through membership in predefined categories such as children, prisoners, or the economically disadvantaged [5] [21]. While pragmatically simple, this approach has been criticized for being both over-inclusive and under-inclusive, potentially stereotyping individuals and overlooking context-specific vulnerabilities [21] [20].

The analytical framework addresses these shortcomings by reframing vulnerability as a dynamic and relational state, rather than a fixed property of an individual or group [21] [20]. As articulated in the 8th revision of the Declaration of Helsinki (2024), individuals or groups may find themselves in "a situation of more vulnerability" due to a combination of fixed, contextual, or dynamic factors [21]. This nuanced view recognizes that a participant's vulnerability can change over the course of a study and can arise from the research design itself, not just from pre-existing participant characteristics [5].

Operationalizing the Frameworks: A Research Lifecycle Workflow

Effectively addressing vulnerability requires a proactive and integrated strategy throughout the entire research process. The following diagram maps the application of the three normative accounts onto key stages of study design, review, and conduct.

Diagram 1: Integrating Vulnerability Assessments into the Research Workflow. LARs = Legally Authorized Representatives.

Experimental and Methodological Implications

Translating the theoretical accounts into actionable research practices requires specific methodological considerations. For instance, a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach is a powerful method for addressing justice-based vulnerabilities. It engages community members as equal partners in designing, implementing, and disseminating research, thereby ensuring the study addresses community priorities and avoids harm [22]. To manage consent-based vulnerabilities, researchers might employ validated competency assessment tools or design multi-stage, simplified consent processes with ongoing comprehension checks [10] [22]. For harm-based vulnerabilities, Data and Safety Monitoring Boards (DSMBs) provide independent oversight, particularly for high-risk studies, to review accumulating data for unexpected adverse events [20].

Essential Toolkit for Ethical Research with Vulnerable Participants

Navigating the ethical landscape of vulnerability requires a set of conceptual and practical tools. The following table functions as a "scientist's toolkit," detailing key resources and their applications grounded in the three normative accounts.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Engagement with Vulnerability

| Tool / Framework | Primary Ethical Account | Function in Research Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Belmont Report Principles [5] [20] | Foundational | Provides the three foundational ethical principles (Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice) that underpin all modern research ethics and the specific accounts of vulnerability. |

| Analytical Vulnerability Framework [5] [21] | All (Consent, Harm, Justice) | Shifts the focus from labelling groups to analyzing situational and contextual sources of vulnerability, enabling more precise and respectful protections. |

| Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) [22] | Justice-Based | A collaborative approach to research that equitably involves community partners in the process to build trust, ensure relevance, and share power. |

| Enhanced Consent Protocols [5] [10] | Consent-Based | Procedures beyond standard consent, such as using independent consent monitors, surrogate decision-makers, and culturally/linguistically adapted materials. |

| Stakeholder Engagement Process [20] | Justice-Based | A structured process for involving patients, advocates, and community representatives in protocol development and review to identify and mitigate potential injustices and harms. |

| Dynamic Risk Assessment [21] | Harm-Based | A continuous process of evaluating potential harms that considers how a participant's vulnerability may change during the study, requiring adaptable safeguards. |

The consent-based, harm-based, and justice-based accounts of vulnerability provide a sophisticated and necessary framework for contemporary research ethics. Moving beyond static checklists of vulnerable groups, this analytical approach demands that researchers, scientists, and regulators critically assess the specific reasons why an individual or population might be at elevated risk within a given research context [5] [21] [20]. The ultimate goal is not to exclude vulnerable populations from research—which can perpetuate injustice and health disparities—but to include them with appropriate, carefully considered protections in place [21]. By systematically applying these normative justifications throughout the research lifecycle, from initial design to final dissemination, the scientific community can uphold its ethical obligations while advancing knowledge that is both robust and equitable.

This technical guide examines the profound and enduring influence of the Belmont Report on modern research ethics guidelines, with particular focus on the protection of vulnerable populations. Through systematic analysis of current literature and regulatory frameworks, we trace the evolution of ethical principles from their foundational expression in 1979 to their contemporary operationalization in global research standards. The analysis demonstrates how the Report's three ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—have fundamentally reshaped regulatory approaches to vulnerability, transitioning from rigid categorical protections toward more nuanced, context-sensitive frameworks. Current systematic reviews of policy documents reveal ongoing challenges in consistently defining and protecting vulnerable populations, while emerging regulatory trends for 2025 indicate continued refinement of these Belmont-inspired protections. This whitepaper provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with both theoretical understanding and practical methodologies for implementing these ethical frameworks in contemporary clinical research environments.

The Belmont Report, formally titled "Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research," was published in 1979 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [23]. This landmark document emerged against a backdrop of historical ethical abuses in research and was designed to identify comprehensive ethical principles for human subjects research [24]. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now Health and Human Services) subsequently incorporated the Report's principles into federal regulations, forming the core of what became known as the Common Rule (45 CFR 46) [23].

The Report's enduring significance lies in its articulation of three fundamental ethical principles that continue to govern human subjects research: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [23]. These principles established a coherent framework that has demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability to evolving research paradigms over more than four decades. The Report's conceptualization of vulnerable populations as those in a "dependent state and with a frequently compromised capacity to free consent" established the foundation for all subsequent ethical guidelines addressing research with vulnerable groups [5].

Table: Historical Context of the Belmont Report

| Timeline | Document/Event | Significance for Vulnerable Populations |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code | Emphasized voluntary consent but lacked provisions for vulnerable groups unable to provide consent |

| 1964 | Declaration of Helsinki (1st version) | Distinguished therapeutic/non-therapeutic research but provided limited protection frameworks |

| 1974 | National Research Act | Established National Commission that would draft the Belmont Report |

| 1979 | Belmont Report | First comprehensive ethical framework explicitly addressing vulnerable populations |

| 1980s-1990s | Common Rule Implementation | Codified Belmont principles with specific subparts for vulnerable populations |

The Belmont Report's Ethical Framework and Vulnerable Populations

The Belmont Report's treatment of vulnerable populations represents a sophisticated balance between protection and inclusion, establishing guiding principles that remain relevant to contemporary research ethics.

The Three Ethical Principles

The Report established three fundamental principles that collectively address the ethical dimensions of research with vulnerable populations:

Respect for Persons: This principle incorporates two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [23]. The Report acknowledges that autonomy is not absolute and that some individuals require extensive protection, potentially even to the point of excluding them from harmful research [23]. This principle recognizes that vulnerability often stems from compromised autonomy and establishes corresponding protections.

Beneficence: Going beyond simply avoiding harm, this principle requires researchers to make positive efforts to secure participants' well-being [23]. The complementary expressions of this principle—"(1) do not harm and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms"—create affirmative obligations toward all research subjects, with special significance for vulnerable populations who may bear disproportionate risks [23].

Justice: This principle addresses the fair distribution of research burdens and benefits, requiring that subject selection be equitable and not systematically directed toward vulnerable groups simply because of their availability or compromised position [23]. The Report explicitly connects justice to vulnerability by prohibiting the selection of subjects due to "easy availability, compromised position, or racial, sexual, economic, or cultural biases" [23].

Conceptualizing Vulnerability

The Belmont Report introduced a nuanced understanding of vulnerability that acknowledged both inherent and situational factors. The Report defined "vulnerable people" as those in a "dependent state and with a frequently compromised capacity to free consent," specifically mentioning racial minorities, economically disadvantaged people, the very sick, and the institutionalized as examples [5]. This conceptualization acknowledged that vulnerability could arise from various sources while recognizing that the "extent of protection afforded should depend upon the risk of harm and the likelihood of benefit" [23].

Evolution from Belmont to Contemporary Regulatory Frameworks

The transition from the Belmont Report's principlism to contemporary regulatory frameworks reveals both continuity and evolution in the protection of vulnerable populations, with significant developments in how vulnerability is conceptualized and operationalized.

Regulatory Codification: The Common Rule

The Belmont principles were codified into federal regulations through the Common Rule (45 CFR 46), which implemented specific subparts providing additional protections for vulnerable populations:

- Subpart B: Additional protections for pregnant women, human fetuses, and neonates

- Subpart C: Additional protections for prisoners

- Subpart D: Additional protections for children

This regulatory structure reflected what contemporary scholars term the "category" or "group-based notion" of vulnerability, also known as the "labelling approach" [5]. This approach identifies vulnerability based on membership in predetermined groups (e.g., children, prisoners, pregnant women) and establishes specific protections for each category [5]. While pragmatically simpler for research ethics committees, this approach has been criticized for its potential to be both over-inclusive and under-inclusive in identifying vulnerability [5].

The Analytical Approach to Vulnerability

Contemporary research ethics has witnessed the emergence of an analytical approach that shifts focus from categorical labels to the underlying sources and conditions of vulnerability [5]. This approach provides three main accounts of vulnerability:

- Consent-based accounts: Vulnerability stems primarily from compromised capacity to provide free and informed consent due to conditions such as undue influence, limited decision-making capacity, or situational pressures [5].

- Harm-based accounts: Vulnerability is conceptualized as an increased probability of incurring harm during research, requiring enhanced safeguards regardless of categorical group membership [5].

- Justice-based accounts: Vulnerability arises from unequal conditions and opportunities that create disparities in research participation or benefit distribution [5].

Table: Comparative Approaches to Vulnerability in Research Ethics

| Aspect | Categorical (Group-Based) Approach | Analytical Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Identifies vulnerability based on group membership | Identifies vulnerability based on individual and contextual factors |

| Examples | Children, prisoners, pregnant women, cognitively impaired | Those with compromised consent capacity, elevated risk of harm, or subject to unjust distribution of risks/benefits |

| Regulatory Preference | Historically dominant, simpler to implement | Increasingly favored in theoretical literature |

| Practical Implementation | Clearer boundaries but potentially rigid | More nuanced but operationally challenging |

| Coverage | May miss vulnerable individuals outside predefined categories | Potentially more comprehensive but less predictable |

Current Landscape: Systematic Analysis of Policy Guidelines

Recent comprehensive analysis of policy documents reveals how vulnerability is conceptualized and operationalized in contemporary research ethics frameworks. A 2025 systematic review of policy documents published in PLOS ONE analyzed 79 policy guidelines to provide a comprehensive overview of vulnerability in research ethics [5] [13].

Key Findings from the Systematic Review

The systematic review identified several recurring patterns in how policy documents address vulnerability:

Definitional Tendencies: Most policy documents demonstrate a preference for identifying and defining specific vulnerable groups rather than providing a general definition of vulnerability itself [5] [13]. This reflects the persistent influence of the categorical approach despite theoretical preference for analytical frameworks.

Informed Consent Focus: Policy documents frequently define vulnerability in relation to informed consent capacity, echoing the Belmont Report's emphasis on persons with diminished autonomy [5] [13]. This consent-based account remains dominant in operational definitions.

Protection-Participation Tension: The review identified ongoing tension between protecting vulnerable populations from harm and ensuring their appropriate participation in research [5]. Historically, strict protectionist approaches sometimes resulted in exclusion from research and its potential benefits, perpetuating injustices [5].

Emerging Regulatory Trends for 2025

Analysis of forthcoming regulatory changes indicates continued evolution in the protection of vulnerable populations:

Enhanced Focus on Diverse Enrollment: Regulatory agencies are increasing emphasis on diverse participant enrollment, including vulnerable populations, to ensure treatments are effective across patient demographics [25]. This represents a practical application of the justice principle.

Single IRB Review for Multicenter Studies: Implementation of single IRB review for multicenter studies aims to streamline ethical review while maintaining protection standards [25]. This structural change may promote more consistent application of vulnerability assessments across research sites.

ICH E6(R3) Updates: New international standards for clinical trials emphasize data integrity and traceability, with implications for the ethical conduct of research involving vulnerable populations [25].

Methodological Framework: Implementing Ethical Principles in Research with Vulnerable Populations

Translating ethical principles into practical research methodologies requires systematic approaches to identifying and addressing vulnerability. The following section provides researchers with concrete frameworks for implementing Belmont-inspired ethics in contemporary studies.

Experimental Protocol for Vulnerability Assessment

Protocol Title: Comprehensive Vulnerability Assessment and Mitigation Framework for Human Subjects Research

Objective: To provide a systematic methodology for identifying, assessing, and addressing vulnerabilities in research participants throughout the study lifecycle.

Materials and Equipment:

- Vulnerability assessment checklist (context-specific)

- Informed consent evaluation toolkit

- Risk-benefit assessment matrix

- Cultural and linguistic appropriate communication resources

- Data protection and confidentiality protocols

Procedure:

Pre-Study Vulnerability Mapping

- Conduct stakeholder engagement with community representatives from potentially vulnerable groups

- Identify contextual factors that may create or exacerbate vulnerability in the specific research setting

- Document potential vulnerabilities in research protocol

Participant-Level Assessment

- Implement individualized evaluation of consent capacity using validated assessment tools

- Identify situational factors that may compromise voluntary participation (e.g., power differentials, economic pressures)

- Assess understanding of research concepts through teach-back methods

Continuous Monitoring and Reassessment

- Establish mechanisms for ongoing evaluation of participant vulnerability throughout study participation

- Implement procedures for dynamic consent where understanding may fluctuate

- Document and address emerging vulnerabilities through protocol modifications

Post-Study Evaluation

- Assess distribution of risks and benefits across participant subgroups

- Evaluate whether vulnerability protections resulted in equitable participation

- Incorporate lessons learned into future study designs

Validation: This protocol draws from systematic analysis of 79 policy documents [5] [13] and incorporates best practices identified in recent literature on engaging vulnerable populations in research [26]. The framework balances categorical and analytical approaches to vulnerability, acknowledging the regulatory requirement to address specific protected groups while remaining responsive to individual and contextual factors.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Ethical Research with Vulnerable Populations

Table: Essential Resources for Ethical Research with Vulnerable Populations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Components | Function in Protecting Vulnerable Populations |

|---|---|---|

| Consent Enhancement Tools | Simplified consent forms, Multimedia consent materials, Teach-back assessment protocols, Witness verification procedures | Enhance comprehension and ensure genuine informed consent for those with cognitive, educational, or linguistic vulnerabilities |

| Capacity Assessment Instruments | MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool, UBACC, SICIATRI | Objectively evaluate decision-making capacity and identify need for additional protections or proxy consent |

| Cultural and Linguistic Resources | Certified translators, Culturally validated assessment tools, Community navigators | Address vulnerabilities arising from language barriers or cultural differences |

| Data Protection Systems | Secure encrypted databases, Limited access protocols, Anonymization techniques | Protect vulnerable participants from privacy breaches and associated harms |

| Community Engagement Frameworks | Community Advisory Boards, Participatory research designs, Benefit-sharing agreements | Address justice-based vulnerabilities through meaningful community involvement |

Visualization of Ethical Framework Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the systematic application of Belmont Report principles to the protection of vulnerable populations in research, mapping the relationship between core ethical principles, their applications, and resulting protections.

Diagram: Ethical Framework for Vulnerable Population Protection. This visualization maps the evolution from Belmont Report principles to contemporary approaches for protecting vulnerable research populations, demonstrating the relationship between core ethical principles and their practical applications.

Discussion: Contemporary Challenges and Future Directions

The enduring influence of the Belmont Report presents both strengths and challenges for modern research ethics. The tension between categorical and analytical approaches to vulnerability reflects deeper philosophical questions about how best to operationalize ethical principles in diverse research contexts.

Implementation Challenges

Research ethics committees frequently maintain preference for the categorical approach to vulnerability as a "pragmatically simpler solution" despite theoretical recognition that the analytical approach is more nuanced and context-sensitive [5]. This creates practical challenges for researchers who must navigate sometimes inconsistent interpretations of vulnerability across different review boards.

Furthermore, the systematic review of policy documents reveals that research ethics committees often require statements about vulnerable population enrollment without providing specific guidance on implementation, potentially resulting in "differential treatment of vulnerable research subjects with potentially inequitable outcomes" [5]. This guidance gap may lead researchers to exclude traditionally vulnerable groups due to management difficulties rather than ethical considerations [5].

Balancing Protection and Participation

Contemporary ethical frameworks increasingly recognize that both exclusion and exploitation of vulnerable populations can constitute ethical failures [26]. As noted by experts in the field, "excluding the vulnerable is biased and unethical," yet inclusion requires sophisticated approaches to distinguish "between coercion and fair compensation while respecting the principles of informed consent" [26].

The evolution toward appropriate inclusion reflects a maturation beyond the protectionist paradigm that initially followed the Belmont Report. Where early implementations often emphasized restrictions on vulnerable population enrollment, modern approaches recognize that "individuals from all these populations may legitimately participate in clinical trials under ethical and well-managed conditions" [26].

Regulatory Innovation and Future Trends

Emerging regulatory trends for 2025 suggest continued refinement of vulnerability protections, with emphasis on diverse enrollment, streamlined ethical review processes, and enhanced data integrity requirements [25]. These developments represent practical implementations of the justice principle, ensuring equitable distribution of research benefits and burdens while maintaining appropriate safeguards.

Future directions likely include greater integration of community engagement in vulnerability assessment, development of more sophisticated consent models for fluctuating capacity, and increased attention to structural vulnerabilities arising from social determinants of health. The ongoing revision of international guidelines such as ICH E6(R3) indicates continued global convergence toward ethically robust yet practical frameworks for vulnerable population research [25].

The Belmont Report's enduring influence on modern research guidelines demonstrates the remarkable resilience of its ethical framework. Its three principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—have successfully guided research ethics for over four decades while adapting to evolving understandings of vulnerability and protection. The contemporary landscape reflects a maturation from rigid categorical protections toward more nuanced, context-sensitive approaches that balance safeguarding against exploitation with appropriate inclusion.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this regulatory evolution is essential for designing ethically sound studies that both protect and appropriately include vulnerable populations. The systematic methodologies and frameworks presented in this whitepaper provide practical tools for implementing these ethical principles in current research environments. As regulatory standards continue to evolve, the Belmont Report's foundational principles remain remarkably relevant for addressing emerging ethical challenges in human subjects research.

Practical Protocols: Implementing Ethical Safeguards in Study Design and Conduct

In life science research and development, including diverse populations is critical for ensuring scientific rigor and generalizability of research findings. Historically, this has not been accomplished for many reasons, including racial and gender biases, differential access to medical care, and varied enrollment in clinical trials across different populations, geographical regions, and countries. For vulnerable populations specifically, these barriers compound existing health disparities, creating ethical challenges that demand systematic solutions. The scientific imperative is equally compelling; without adequate representation, research findings may lack external validity and fail to account for biological, genetic, and social factors that influence disease presentation and treatment response across different populations.

Advancing inclusive research (AIR) requires frameworks and metrics for assessing real-world data and measuring population science. Because different factors drive health inequities and variables in measuring population science, relying on one metric for measuring progress may have limitations. This technical guide presents a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing inclusive research protocols that ensure equitable participation and benefit distribution, with particular attention to vulnerable populations within research ethics. The principles and methodologies outlined herein address both the ethical obligations to ensure equitable access to research benefits and the methodological necessities for producing scientifically valid, generalizable results.

Theoretical Framework: Foundational Principles for Inclusive Research

The 5Ps Framework for Advancing Inclusive Research

The 5 Principles (5Ps) framework provides a conceptual foundation designed to ensure a study is representative to the extent possible—based on data availability, operational constraints, and regulatory requirements—and adheres to biomedical ethical principles. These five principles form the basis for a data-informed framework to measure and systematically define inclusive research to ensure rigor and benchmarking within organizations and across the broader sector [27].

The framework standardizes processes by which inclusive research and clinical trials can be conducted in an organization, allowing for benchmarking, performance assessments, and integration of health equity and inclusive research at a population level. For vulnerable populations, this systematic approach is particularly crucial as it provides measurable accountability for inclusion that has historically been neglected.

Table 1: The 5Ps Framework for Advancing Inclusive Research

| Principle | Core Focus | Key Considerations for Vulnerable Populations |

|---|---|---|

| Population Science | Biological, genetic, and demographic considerations | Responsible use of population descriptors; understanding social determinants of health; addressing underrepresentation in baseline data |

| Data-Informed Site Placement | Geographical distribution of research sites | Ensuring site locations align with disease burden in vulnerable communities; geographical proportionality in trial enrollment |

| Inclusive Trial Design | End-to-end inclusive protocol development | Removing unnecessary exclusion criteria; addressing practical barriers to participation; incorporating community feedback |

| Patient-Reported Data Standards | Integration of patient perspectives | Ensuring complete and consistent data collection across diverse populations; culturally appropriate measurement tools |

| Trial Access Enablement | Practical support for participation | Addressing financial, logistical, and trust barriers; patient navigation assistance; demonstrating trustworthiness to communities |

Measuring Representativeness: The Participation-to-Prevalence Ratio

A critical metric for assessing inclusion is the participation-to-prevalence ratio (PPR), calculated by dividing the percentage of a particular population among the study participants by the percentage of that population in the disease population. A range of 80–120% has been suggested as adequate representation, where each study should aim for zero error between these proportions [27]. For example, if women constitute 40% of a disease population but only 20% of a trial's participants, the PPR would be 50% (20/40), indicating significant underrepresentation.

This metric is particularly valuable for vulnerable populations as it provides a quantitative benchmark for evaluating inclusion and identifying disparities in enrollment. When applied systematically across multiple studies, it enables performance tracking and accountability in addressing historical underrepresentation.

Methodological Implementation: Protocols for Inclusive Research Design

Population Science Considerations in Protocol Development

The first principle anchors on the "Who," i.e., who is most affected by the disease or condition? Collecting diverse biological, genetic, and demographic data is essential for understanding patient outcomes, disease risk, and enrollment rates. Race and ethnicity are social constructs, with different interpretations that have led to the exclusion of certain populations in clinical research. Genetic ancestry is often oversimplified to broad continental categories, undermining scientific objectivity and potentially perpetuating harmful stereotypes linked to racial genetic determination [27].

For vulnerable populations, appropriate use of population descriptors is essential. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) recommends the appropriate use of population descriptors in genetics and genomics research. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has updated guidelines to standardize race and ethnicity data collection in clinical studies. These initiatives may enhance the understanding and enrollment of the diverse patient populations in clinical trials [27].

Experimental Protocol: Disease Area Population Analysis

Literature Review Implementation: Conduct a comprehensive literature review of the therapy area to summarize the epidemiology, risk factors, disparities in diagnosis, disease characteristics and progression, genetics, biomarkers, treatment patterns and outcomes, and quality of care in global patient populations with a focus on health equity.

Quality Assessment: Grade studies that meet the criteria using a quality assessment tool for the strength of evidence. Searches and summaries can be done manually or with natural language processing or augmented intelligence tools, keeping biases and limitations in mind.

Disease Burden Measurement: Measure disease burden using demographic-specific variables with standardized metrics, identifying demographic groups with granularity in geographical areas to enable precise benchmarking, while recognizing that most existing sources of data on disease prevalence are biased in the same direction as the problem.

Data-Informed Country and Site Placement Methodology

Once the patient population (biology, genetics, demographics) with the disease is understood, Principle 2 anchors on "Where" these patients are. The FDA issued draft guidance for the creation of Diversity Action Plans (DAPs) by sponsors of pivotal studies to increase enrollment of historically underrepresented populations to improve the strength of the evidence for the intended-use population [27].

Experimental Protocol: Geographical Site Selection

Epidemiological Data Identification: Identify preferred sources, such as the US Cancer Statistics (USCS) and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Global Burden of Disease study, based on data quality, representativeness, and disease area coverage to provide epidemiology estimates at the indication or disease area level.