Empirical Bioethics Methodology: Assessing Rigor, Navigating Standards, and Implementing Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive framework for assessing methodological rigor in empirical bioethics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Empirical Bioethics Methodology: Assessing Rigor, Navigating Standards, and Implementing Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for assessing methodological rigor in empirical bioethics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational challenges and consensus standards defining the field, details practical methodological approaches for integrating empirical and normative analysis, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for interdisciplinary work, and presents validation and comparative techniques for evaluating research quality. By synthesizing current evidence and established guidelines, this guide aims to enhance the design, conduct, and critical appraisal of empirical bioethics research within biomedical and clinical contexts.

Defining Rigor in Empirical Bioethics: Core Concepts and Consensus Standards

A fundamental challenge lies at the heart of empirical bioethics: the is-ought problem. First clearly articulated by the Scottish philosopher David Hume, this problem questions the logical validity of inferring prescriptive statements (about what ought to be) from purely descriptive, factual statements (about what is) [1]. Hume noted that authors of moral systems often make this leap imperceptibly, without explaining how these fundamentally different types of relations connect [1]. This creates a significant methodological challenge for empirical bioethics, a field that explicitly seeks to integrate empirical data from social science with normative ethical analysis to draw practical conclusions [2]. The problem is not merely academic; it strikes at the very validity of the field's conclusions. If normative claims cannot be logically derived from empirical observations, then the entire project of using patient preferences, clinical observations, or sociological data to inform ethical guidelines appears philosophically dubious. This guide compares how different methodological approaches within empirical bioethics attempt to bridge this divide, assessing their rigor and effectiveness in addressing this foundational challenge.

Methodological Frameworks for Integration

Philosophical Foundations and the Scope of the Challenge

The is-ought problem, also referred to as Hume's law or Hume's guillotine, posits that an ethical conclusion cannot be logically deduced from entirely non-ethical premises [1]. In modern research terms, this creates a gap between the empirical data collected about practices, attitudes, or experiences (the is) and the normative recommendations or ethical evaluations that bioethics seeks to produce (the ought). This gap is further complicated by what is known as the fact-value distinction in epistemology [1]. For bioethics researchers, this means that simply gathering robust data on, for example, how clinicians actually behave in difficult situations is not, in itself, sufficient to determine how they should behave. The challenge is to develop methodologies that can traverse this gap in a philosophically sound and methodologically rigorous manner.

Comparative Analysis of Key Methodological Approaches

Bioethics researchers have developed several innovative methodological frameworks to tackle this challenge. The table below provides a structured comparison of three prominent approaches, highlighting their core strategies for integration and their relative strengths and weaknesses.

| Methodological Approach | Core Integration Strategy | Key Strengths | Principal Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Interpretive Synthesis | Empirical data is used to critically interrogate and refine existing ethical concepts and theories, creating a new, empirically informed theoretical framework [2]. | Generates novel theoretical insights; avoids simply mapping data onto pre-existing categories; dynamic and iterative process [2]. | Can be theoretically complex; may be difficult to achieve transparency; requires high-level interpretive skill [2]. |

| Reflective Equilibrium | Seeks coherence between empirical data, ethical principles, and considered moral judgments through a process of continuous adjustment [2]. | Systematizes a process of moral justification familiar from everyday reasoning; allows for revision of principles in light of cases [2]. | Can be circular if not carefully practiced; may privilege certain intuitions; achieving equilibrium can be subjective [2]. |

| Procedure-Based Models | Uses structured deliberative procedures (e.g., expert panels, stakeholder dialogues) to interpret empirical findings and derive normative conclusions [2]. | Enhances legitimacy through participatory processes; makes the normative deliberation transparent and structured [2]. | Conclusions are only as good as the procedure itself; can be resource-intensive; risk of conflating consensus with correctness [2]. |

Experimental Protocols and Analytical Workflows

To ensure methodological rigor, researchers must carefully design their studies from inception to completion. The following workflow, formally outlined in consensus standards for empirical bioethics research, provides a structured pathway for integrating empirical and normative analysis [2]. This process is designed to make the bridging of the is-ought gap explicit, transparent, and systematic.

Detailed Protocol for Integrated Empirical-Normative Research

This protocol operationalizes the workflow above, providing concrete steps for researchers to follow.

Phase 1: Foundational Scoping & Question Formulation

- Step 1: Define an interdisciplinary aim that explicitly requires both empirical and normative components to answer [2]. The aim should explain why a mono-disciplinary approach is insufficient.

- Step 2: Formulate specific, interlinked empirical and normative research questions. Example: Empirical: "What are the lived experiences of patients in prolonged disorder of consciousness?" Normative: "What weight should patient biography, as narrated by families, hold in surrogate decision-making?" [2].

- Step 3: Select and justify a specific methodological framework for integration (e.g., from the comparison table above) that is appropriate for the research questions.

Phase 2: Interdisciplinary Conduct & Analysis

- Step 4: Conduct Empirical Work: Collect and analyze data using methods from social science (e.g., interviews, surveys, ethnography). Researchers must demonstrate methodological competence by adhering to established standards of rigor from the relevant empirical discipline (e.g., qualitative research trustworthiness criteria) [2].

- Step 5: Conduct Normative Analysis: Analyze the ethical issue using tools from moral philosophy (e.g., principle-based analysis, casuistry, virtue ethics). This must involve more than simply applying a pre-determined conclusion; it should be a robust analysis engaging with ethical theory and literature [2].

- Step 6: Integration: This is the crucial bridging phase. Apply the chosen methodological framework (e.g., Reflective Equilibrium, Critical Interpretive Synthesis) to interrelate the empirical findings and the normative analysis. This step must be made transparent, explaining how the data is informing the ethical evaluation and vice-versa [2].

Phase 3: Conclusion & Validation

- Step 7: Draw and articulate the normative conclusion, explicitly acknowledging the role the empirical data played in its formation and any limitations or constraints this places on the conclusion.

- Step 8: Disseminate findings in a way that is accessible to both empirical and normative disciplines and engage in critical reflection on the process itself, contributing to methodological advancement [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Rigorous Research

Successful navigation of the empirical-normative divide requires specific conceptual tools and methodological "reagents." The following table details key components necessary for conducting robust empirical bioethics research, as outlined in consensus standards [2].

| Research 'Reagent' | Function & Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Interdisciplinary Research Question | Forces the research to engage with both empirical and normative domains from the outset, preventing a mere "add-on" of one to the other [2]. | "How do neonatal intensive care unit staff conceptualize 'best interests' (empirical), and how should these conceptions inform a framework for resolving disagreements between staff and parents (normative)?" |

| Explicit Integration Framework | Provides the logical and methodological structure for combining empirical data and normative analysis, making the process transparent and defensible [2]. | Using the procedure of Reflective Equilibrium to adjust one's considered judgments about privacy in light of empirical data on public attitudes toward data sharing. |

| Transparent Normative Foundations | The ethical theories, principles, or concepts used in the analysis. Making them explicit allows for critical evaluation of the normative work [2]. | Stating that the analysis will employ a capabilities approach (as developed by Nussbaum and Sen) to evaluate the ethics of cognitive enhancement technologies. |

| Rigorously Generated Empirical Data | Data collected and analyzed according to the standards of the relevant social science discipline, ensuring the factual 'is' being incorporated is valid and reliable [2]. | Using thematic analysis with double-coding and consensus meetings to analyze interview transcripts about decision-making processes. |

| Deliberative Forum | A structured procedure (physical or virtual) that brings together diverse stakeholders to discuss and interpret the implications of empirical findings for normative questions [2]. | Convening a mixed panel of patients, clinicians, and ethicists to deliberate on the findings of a survey about the acceptability of novel genetic technologies. |

The is-ought gap remains a permanent feature of the philosophical landscape, but it is not an insurmountable barrier for empirical bioethics. As this guide has demonstrated, through the conscious application of rigorous methodological frameworks like Critical Interpretive Synthesis and Reflective Equilibrium, and by adhering to structured experimental protocols, researchers can build credible bridges across the divide. The validity of this interdisciplinary project no longer rests on claiming to have solved Hume's problem, but on transparently demonstrating how carefully gathered empirical evidence can inform and enrich robust normative reasoning. The future methodological rigor of the field depends on its practitioners continuing to refine these approaches, explicitly detailing their integrative strategies, and subjecting them to ongoing critical peer review.

Bioethics, since its emergence as a distinct field of inquiry, has been characterized by a fundamental tension: it addresses profoundly normative questions concerning life, health, and death, yet it does so by drawing upon a diverse array of disciplinary methods, from philosophy and law to sociology and empirical psychology. This inherent interdisciplinarity has fueled a long-standing debate about its very disciplinary status and, crucially, whether it possesses established, internal methodological rules [3]. While some refer to bioethics as a discipline in its own right, others label it a "field," "demi-discipline," or an "interdisciplinary" or "multidisciplinary" endeavor [3]. This terminological disagreement points to a more profound methodological uncertainty. The central challenge is that each discipline bioethics draws from—whether philosophy, medicine, or social science—comes with its own standard of rigor, its own criteria for determining valid and truthful results [3]. When these perspectives converge, as they must in bioethics, what constitutes methodological rigor? This question is not merely academic; it has serious implications for the legitimacy, authority, and practical impact of bioethical scholarship [3].

This article examines the ongoing discipline debate in bioethics by comparing the arguments for methodological plurality against the emerging consensus on standards of practice. It assesses the field's methodological rigor through the lens of a structured, comparative framework, presenting quantitative data on methodological trends and qualitative analysis of established protocols. By framing the discussion as a comparison between traditional philosophical inquiry and the rising paradigm of empirical bioethics, this guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear understanding of the methodological landscape and the tools to navigate it rigorously.

Comparative Analysis of Bioethics Methodological Frameworks

The table below summarizes the core positions in the debate regarding bioethics' methodological identity, highlighting the associated challenges and the evolving responses to them.

Table: Comparative Frameworks in the Bioethics Methodology Debate

| Framework | Core Tenets | Strengths | Weaknesses & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Philosophical Bioethics | Relies on classical philosophical methods: conceptual analysis, normative argumentation, and casuistry [4]. | Provides a strong foundation for normative reasoning and the development of ethical principles like autonomy and justice [4]. | Can be abstract; may lack grounding in the realities of clinical practice and stakeholder perspectives [4]. |

| Empirical Bioethics | Integrates data-driven research from social sciences (e.g., surveys, interviews) with ethical analysis to inform normative conclusions [4] [2]. | Grounds ethical reflection in actual practices, beliefs, and experiences, making it highly relevant to clinicians and patients [4]. | Faces the "is-ought" challenge; requires sophisticated methods for integrating descriptive data with normative reasoning [4] [2]. |

| Experimental Bioethics ("Bioxphi") | A subdiscipline using experiment-based designs from cognitive sciences (psychology, neuroscience) to understand how and why stakeholders make moral judgments [5]. | Offers high internal rigor and can reveal cognitive biases and psychological mechanisms underlying moral intuitions [5]. | Findings may be context-specific; the path from psychological findings to normative conclusions remains complex [5]. |

| The "Consensus" Movement | Seeks to establish agreed-upon Standards of Practice for empirical bioethics to ensure quality and rigor [2]. | Addresses the "quality crisis" directly; provides concrete guidance for researchers, funders, and journals [2]. | May be perceived as overly rigid; consensus is difficult to achieve in a fundamentally interdisciplinary field [2]. |

The Implications of Methodological Pluralism

The lack of a single, unifying methodology has spawned several significant challenges that undermine the field's credibility and effectiveness [3]:

- Theoretical & Epistemological Challenges: There are no clear, universally accepted standards for assessing competing normative conclusions derived from different methodological starting points [3].

- Peer Review Challenges: The criteria for "good scholarship"—originality, quality, validity—are interpreted differently across disciplines, creating inconsistency and confusion in the review process for bioethics journals [3].

- Sociological & Authority Challenges: The absence of agreed-upon standards can undermine the claims to authority, credibility, and legitimacy of bioethics researchers, particularly in the public sphere [3].

- Clinical Decision-Making Challenges: In healthcare settings, the lack of a clear framework for balancing different disciplinary perspectives can hinder effective and justified ethical decision-making [3].

- Institutional & Pedagogical Challenges: Uncertainty about the field's core methods complicates curriculum development, bioethics education, and its place within university structures [3].

Established Methodological Rules: The Emergence of Standards

In response to these challenges, significant efforts have been made to formalize methodological rules, particularly within the domain of empirical bioethics. A key consensus project, which utilized a modified Delphi process with 16 academics from five European countries, successfully established 15 standards of practice for empirical bioethics research. These standards are organized into six domains, providing a concrete framework for assessing methodological rigor [2].

Table: Consensus Standards for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Domain | Description of Standards |

|---|---|

| Aims | Research must clearly articulate its aims and the specific bioethical problem it addresses [2]. |

| Questions | The research questions must be framed to require both empirical and normative analysis for their answer [2]. |

| Integration | The methodology must explicitly describe and justify how the empirical and normative components will be integrated throughout the research process, rather than being merely juxtaposed [2]. |

| Conduct of Empirical Work | The empirical work must be designed, conducted, and reported according to the established quality criteria of the relevant social scientific discipline (e.g., qualitative or quantitative research standards) [2]. |

| Conduct of Normative Work | The normative analysis must be conducted and reported according to recognized standards of philosophical or ethical rigor, with transparent reasoning and engagement with relevant ethical theories and concepts [2]. |

| Training & Expertise | The research team must possess, or have access to, adequate expertise in both the empirical methods and the normative analysis required for the project [2]. |

This consensus represents a major step towards disciplining the field. It provides journals, funders, and researchers with a shared set of expectations, addressing the peer review and legitimacy challenges head-on. The standards emphasize that rigor in empirical bioethics is not just about doing good empirical work or good normative work, but about systematically integrating the two [2].

A Hierarchical Model for Empirical Research

Further structuring the empirical turn, one proposed framework classifies empirical research in bioethics into four hierarchical categories, each building upon the last [4]. This model provides a clear "experimental protocol" for designing and categorizing studies.

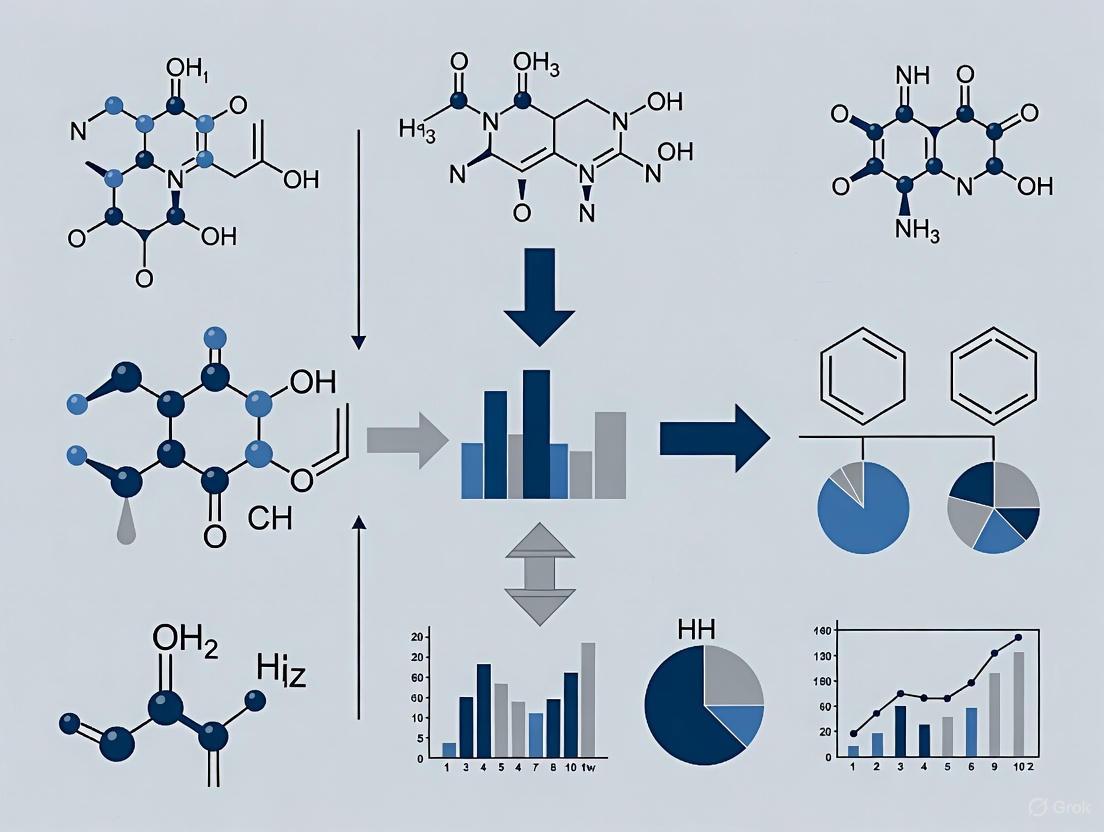

Diagram: The Hierarchical Progression of Empirical Bioethics Research

- Level 1: Lay of the Land - This foundational research describes current practices, opinions, or beliefs. Examples include surveys of what patients want in end-of-life care or studies examining the composition of hospital ethics committees [4].

- Level 2: Ideal Versus Reality - This research starts with an accepted ethical norm (e.g., "informed consent must be comprehended by research subjects") and tests whether reality aligns with this ideal. The vast body of work on racial disparities in healthcare is a prime example of this category [4].

- Level 3: Improving Care - Studies at this level develop and assess interventions to bring clinical practice closer to ethical ideals, such as testing a new communication tool to improve the informed consent process [4].

- Level 4: Changing Ethical Norms - The highest level of work, which synthesizes data from multiple empirical studies to inform, challenge, and potentially revise our ethical norms and principles [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Reagents

For researchers embarking on a bioethics project, the following "reagents"—core methodological components and documents—are essential for ensuring rigor and ethical compliance.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Methodologically Rigorous Bioethics

| Research Reagent | Function & Role in Ensuring Rigor |

|---|---|

| Study Protocol | Serves as the comprehensive blueprint for the study, detailing objectives, design, methodology, and statistical considerations. It is the foundational document for ethical and scientific review [6]. |

| Informed Consent Form (ICF) | The primary tool for upholding the ethical principle of autonomy. It must provide all necessary information in plain language, allowing potential participants to make a fully informed decision [6]. |

| Data Collection Tool (e.g., CRF) | A standardized tool, like a Case Report Form (CRF), ensures consistent, accurate, and unambiguous data collection across all study participants, which is crucial for data integrity [6]. |

| Integration Methodology | The explicit, pre-defined plan for how the empirical (descriptive) and normative (prescriptive) components of the research will be combined to produce coherent, justified conclusions [2]. |

| Ethics Committee (IRB/REC) Approval | Formal approval from a Research Ethics Committee (REC) or Institutional Review Board (IRB) is mandatory. It confirms that the study design respects participant rights, safety, and well-being [7]. |

The Global Ethics Review Landscape

For international research, understanding the variability in ethics review processes is a critical aspect of methodological rigor. A recent 2025 study of 17 countries highlights significant heterogeneity in the timelines and requirements for ethical approval, which can impact the feasibility of collaborative studies [7]. The following workflow visualizes the complex, multi-stage process researchers may face.

Diagram: Workflow for Navigating International Ethical Review

The quantitative data from this study reveals substantial disparities. For example, while some countries require formal ethical approval for all study types, others, like the UK and Slovakia, may waive this for audits or non-interventional studies. Timelines for approval also vary dramatically, from 1-3 months in many regions to over 6 months in countries like Belgium and the UK for interventional studies [7]. This variability underscores the importance of the "Determine Local Ethics Requirements" reagent in the scientist's toolkit.

The debate over whether bioethics has established methodological rules does not yield a simple "yes" or "no" answer. The evidence points to a field that is actively and successfully disciplining itself. While bioethics may never be a monolithic discipline with a single, unified method, the development of consensus standards [2] and the widespread adoption of structured frameworks for empirical research [4] demonstrate a clear trajectory toward methodological maturation.

The core strength of bioethics—its interdisciplinarity—is also the source of its greatest challenge. However, the emergence of explicit standards for integration, rigorous empirical work, and sound normative analysis provides a robust response to critiques about a lack of rigor. For researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development, this means that conducting rigorous bioethics research is entirely possible, provided it is guided by these emerging rules. The methodology is no longer purely aspirational; it is increasingly concrete, demanding, and essential for producing scholarship that can legitimately claim to inform both policy and practice. The discipline debate is thus being resolved not through declaration, but through the progressive, collective establishment of methodological rules that honor the field's complex heritage while ensuring its scientific and ethical credibility.

Assessing Methodological Rigor in Empirical Bioethics Research

Empirical bioethics is an interdisciplinary field that integrates social scientific research with ethical analysis to arrive at normative conclusions. For years, the field has been characterized by a "broad variety of methodologies," which, while innovative, has made it challenging to present, defend, or critically assess the quality of research work [2]. The absence of a clear, agreed-upon standard of rigor poses serious threats to the field, undermining claims to authority, credibility, and legitimacy, and creating challenges for peer review and practical decision-making [3]. In response to these challenges, a group of 16 academics from five European countries convened at the Brocher Foundation in May 2015 with a specific goal: to generate and reach a consensus on standards of practice for empirical bioethics research [2] [8]. Through a modified Delphi process, this group established 15 standards of practice, organized into 6 domains, providing a critical framework for assessing methodological rigor [2]. This guide objectively compares this emerging consensus standard against the prior state of the field, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the tools to implement rigorous empirical bioethics in their work.

The Experimental Protocol: Forging Consensus through a Modified Delphi Method

The development of the 15 standards was itself a rigorous scholarly exercise designed to build consensus among experts with diverse disciplinary backgrounds.

- Research Question: The primary aim was to establish a consensus on the core characteristics of empirical bioethics and to define minimum standards for methodological quality in its design, conduct, and reporting [2].

- Participant Selection: The process involved 16 academics from 5 different European countries, who were purposively selected to represent a range of disciplinary backgrounds and putatively opposing positions within empirical bioethics [2] [8]. This diversity was crucial for ensuring the resulting standards would be robust and widely applicable.

- Consensus Process: The team utilized a modified Delphi approach [2] [8] [9]. The classic Delphi method involves multiple rounds of anonymous questionnaires where panelists reassess their judgments based on summarized group feedback. The modification for this project involved replacing iterative questionnaires with structured group discussions, allowing for immediate clarification of ambiguous or controversial issues—a necessary adaptation given the linguistic and conceptual diversity of the participants [2].

- Outcome Measure: The explicit goal was to generate a set of standards precise enough to provide concrete guidance. Consensus was successfully reached on 15 individual standards, which were then logically grouped into 6 overarching domains of research practice [2].

The following diagram illustrates the structured process used to develop the consensus.

Comparative Analysis: The Brocher Consensus vs. The Pre-Consensus Landscape

The Brocher Consensus can be understood as a direct response to the methodological challenges that plagued the earlier development of empirical bioethics. The table below provides a point-by-point comparison of the research landscape before and after the formulation of these standards.

| Dimension of Comparison | Pre-Consensus Landscape | The Brocher Consensus Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Defining Rigor | No agreed-upon standard of rigor; criteria for truth and validity varied by contributor's home discipline [3]. | Establishes a shared framework for rigor across 6 domains, providing external validation for interdisciplinary work [2]. |

| Methodological Justification | Researchers had to justify every methodological choice "from first principles," a process that was lengthy and difficult [2]. | Provides legitimate starting points and agreed-upon assumptions, streamlining justification for funding and publication [2]. |

| Peer Review | Challenging due to reviewers applying different disciplinary norms; terms like "validity" interpreted inconsistently [3]. | Offers a common benchmark for journals and funders to assess quality, making peer review more consistent and fair [2]. |

| Interdisciplinary Integration | A known challenge with dozens of proposed methodologies, but no consensus on how to validly integrate empirical and normative work [2] [3]. | Makes integration a central domain, requiring researchers to explicitly justify how the empirical and normative parts of their work relate [2]. |

| Training & Expertise | Unclear what skills were essential for a bioethics researcher, leading to potential gaps in training [3]. | Explicitly addresses the need for appropriate training and expertise in both empirical and normative methods [2] [8]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Empirical Bioethics

Executing methodologically rigorous empirical bioethics research requires a suite of conceptual and practical tools. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for this field.

| Tool / Component | Function in Empirical Bioethics Research |

|---|---|

| Modified Delphi Method | A structured communication technique used to achieve consensus among a panel of experts through iterative rounds of discussion and feedback [2]. |

| Explicit Normative Framework | The philosophical or ethical theory (e.g., principlism, consequentialism) that provides the foundation for the normative analysis in the research [2]. |

| Rigorously Designed Empirical Protocol | The detailed methodology for the empirical component (e.g., qualitative interviews, surveys), ensuring social scientific rigor and trustworthiness of the data [2] [4]. |

| Documented Integration Strategy | The clearly articulated procedure for combining empirical findings with normative reasoning, which is the defining core of empirical bioethics [2]. |

| Interdisciplinary Research Team | A collaboration of investigators with complementary expertise in both normative disciplines (e.g., philosophy, law) and empirical disciplines (e.g., sociology, epidemiology) [2] [3]. |

The Empirical-Normative Workflow in Action

A core innovation of the Brocher Consensus is its emphasis on the integration of empirical and normative work. The following diagram maps the logical workflow of a rigorous empirical bioethics project, from its inception to its conclusion, highlighting how these two streams of inquiry interact.

This workflow demonstrates that empirical bioethics is not a simple linear process where data collection merely "informs" ethics. Instead, it is an integrative and often iterative practice where empirical findings and normative analysis are in constant dialogue [2] [4]. The "Integration Process" is the crucial, active component where researchers synthesize the two strands, using methods such as dialectical reflection or case-based reasoning to arrive at justified normative conclusions.

The Brocher Foundation Consensus on 15 standards across 6 domains represents a pivotal achievement in the maturation of empirical bioethics. By moving the field from a state of methodological heterogeneity and contested rigor to one with a shared framework for quality, it directly addresses fundamental challenges related to credibility, peer review, and training [2] [3]. For researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development, engaging with these standards is no longer optional but essential for producing work that can withstand interdisciplinary scrutiny. The consensus is not a final word but an invitation for the community of practice to "develop and evolve further" [2]. The continued adoption and critical engagement with these standards by researchers, funders, and journals will be the ultimate measure of their success in strengthening the methodological rigor of bioethics research.

Empirical bioethics represents an innovative, interdisciplinary field that integrates empirical social scientific research with normative ethical analysis to address complex problems in medicine and the life sciences. This integration aims to ground ethical recommendations in the realities of clinical practice and stakeholder experiences while maintaining philosophical rigor. However, this interdisciplinary nature presents significant methodological challenges, primarily concerning how to establish and maintain rigor when combining descriptive (empirical) and normative (ethical) approaches [3]. The field has been described as both exciting and frustrating—"exciting, because it potentially 'promises a great deal', but also frustrating 'because the emerging field threatens to be so multifarious and vague that making sense of it is a challenge for even the most seasoned researcher'" [10]. This guide objectively compares emerging frameworks and standards designed to enhance methodological rigor in empirical bioethics research, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for conducting and evaluating quality in this complex field.

The fundamental challenge stems from what theorists identify as the "is-ought problem"—the philosophical challenge of deriving normative 'ought' claims from empirical 'is' data [10]. Without clear standards, bioethics research faces five serious practical challenges: (1) no clear standards for answering bioethical questions, (2) problems for peer review processes, (3) undermined claims to authority and legitimacy, (4) difficulties in clinical decision-making, and (5) questions about its proper institutional setting [3]. This comparison guide examines how current methodological frameworks address these challenges through formal, cognitive, and ethical norms.

Comparative Analysis of Quality Criteria Frameworks

Established Standards and Consensus Approaches

A significant development in empirical bioethics methodology emerged from a consensus project involving 16 academics from five European countries using a modified Delphi approach. This project established 15 discrete standards of practice organized into six domains, creating a comprehensive framework for methodological rigor [10].

Table 1: Consensus Standards for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Domain | Number of Standards | Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Aims | Not specified | Clarifying research purposes and interdisciplinary goals |

| Questions | Not specified | Formulating research questions amenable to integration |

| Integration | Not specified | Methodological approaches for combining empirical and normative elements |

| Conduct of Empirical Work | Not specified | Application of appropriate social science methods |

| Conduct of Normative Work | Not specified | Application of appropriate ethical analysis methods |

| Training & Expertise | Not specified | Ensuring researcher competence across disciplines |

The consensus approach argues that establishing agreed-upon standards helps cement empirical bioethics as a distinct 'community of practice' with specific methodological norms, which in turn improves research quality, provides guidance for training, and offers validation for methodological choices during peer review of publications and grant applications [10]. Proponents note that these standards are particularly valuable in an interdisciplinary field where "there is no standard approach to cite, there is no accepted methodology or set of methods to fall back on" [10].

The "Road Map" Framework for Interdisciplinary Research

An alternative but complementary approach has been proposed by Mertz and colleagues, who developed what they term a "road map" for quality criteria in empirical ethics research [11]. This framework organizes criteria into five key domains, presented as reflective questions to guide researchers:

Table 2: Road Map Quality Criteria Framework

| Domain | Key Focus | Sample Reflective Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Research Question | Appropriate scope and interdisciplinary nature | Does the question require both empirical and normative analysis? |

| Theoretical Framework & Methods | Coherent methodological integration | Are empirical methods adequate? Are normative approaches justified? |

| Relevance | Practical significance and impact | Does the research address a pressing ethical problem? |

| Interdisciplinary Research Practice | Collaborative team composition | Does the team have appropriate interdisciplinary expertise? |

| Research Ethics & Scientific Ethos | Ethical conduct of the research itself | Are standard ethical principles for research being followed? |

This framework emphasizes that poor methodology in empirical ethics "results in misleading ethical analyses, evaluations or recommendations" which "not only deprives the study of scientific and social value, but also risks ethical misjudgement" [11]. The road map approach is presented as a heuristic tool to provoke systematic reflection during research planning and composition, positioning quality assurance as an ethical imperative in itself.

Distinguishing Norm Types in Research Practice

Theoretical work on norms provides essential context for understanding different categories of standards applicable to empirical bioethics. Research in cognitive psychology distinguishes between constitutive norms (which define what a practice is) and regulative norms (which guide how the practice should be conducted) [12].

Table 3: Norm Types in Empirical Bioethics Research

| Norm Type | Definition | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Formal Norms | Standards for research writing and dissemination | Reporting standards, publication formats, structural requirements |

| Cognitive Norms | Methodological commitments and analytical approaches | Criteria for valid inference, appropriate methods, analytical rigor |

| Ethical Norms | Moral conduct of research activities | Participant protection, integrity in analysis, responsible reporting |

This distinction helps clarify that methodological rigor in empirical bioethics requires attention to multiple dimensions of quality simultaneously. Formal norms ensure proper research reporting, cognitive norms guarantee the intellectual integrity of the approach, and ethical norms safeguard the moral dimensions of the research process [11]. The psychology of normative cognition suggests that humans develop specialized cognitive mechanisms for learning, complying with, and enforcing norms—a capacity that underpins the methodological standardization now emerging in empirical bioethics [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Implementation

Consensus Development Methodology

The 15-standards framework was developed using a modified Delphi approach that adapted traditional consensus methods to address the conceptual diversity of empirical bioethics [10]. The methodological protocol involved:

- Participant Selection: 16 academics from 5 European countries with diverse disciplinary backgrounds were purposively selected to represent different and potentially opposing positions in empirical bioethics.

- Process Adaptation: Instead of multiple iterative questionnaires typical of Delphi methods, the process used iterative discussion groups with regular feedback sessions.

- Rationale for Adaptation: The modification was justified by "the pressing need to have clear and robust direct verbal communication through discussion that allowed disagreements to be aired and mutually understood" [10].

- Consensus Validation: The process sought to generate standards "precise enough to provide concrete guidance for (a) identifying the core characteristics of empirical bioethics, (b) planning empirical bioethics, (c) conducting empirical bioethics, and (d) reporting empirical bioethics" [10].

This methodological approach recognized that linguistic and conceptual diversity in the field made questionnaire-based approaches problematic, requiring instead a process that allowed immediate clarification of ambiguous or controversial issues.

Implementation Evaluation Methodology

A different methodological approach was used to evaluate how ethical recommendations are translated into practice, employing a cross-sectional mapping study of 400 recent publications from four bioethics journals [14]. The experimental protocol included:

- Sample Identification: The latest 100 publications from each of four bioethics journals (Journal of Medical Ethics, Nursing Ethics, AJOB Empirical Bioethics, BMC Medical Ethics) were identified through PubMed searches.

- Categorization Framework: Publications were categorized as (1) evaluative empirical research (assessing implementation of ethical recommendations), (2) non-evaluative empirical research, or (3) borderline cases using predefined criteria.

- Analysis Method: For evaluative studies, researchers analyzed which types of norms or recommendations were being evaluated, using a framework that distinguished between aspirational norms, specific norms, and best practices.

- Inter-rater Reliability: Screening and categorization were performed independently by two reviewers with disagreements resolved by consensus, and interrater agreement was measured on a random subsample using Cohen's kappa.

This methodology revealed that among recent empirical bioethics publications, 36% (84 of 234 included studies) constituted evaluative empirical research, while 54% were non-evaluative empirical studies, and 10% were borderline cases [14]. This provides quantitative evidence about current research practices and the relative emphasis on different types of empirical approaches in the field.

Visualization of Methodological Integration

The following diagram illustrates the integrated relationship between different norm types and research components in empirical bioethics, showing how quality criteria interact across the research lifecycle:

Diagram 1: Integration of Norm Types in Research

Successful empirical bioethics research requires specific methodological competencies and resources. The following table details essential components of the empirical bioethics research toolkit:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Empirical Bioethics

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Approaches | Function in Research Process |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical Data Collection | Qualitative interviews, focus groups, surveys, observational studies, systematic reviews | Generates robust empirical data about ethical issues in practice |

| Normative Analysis Frameworks | Principlism, casuistry, consequentialist analysis, deontological approaches, virtue ethics | Provides structured methods for ethical analysis and argument development |

| Integration Methodologies | Reflective equilibrium, symbiotic ethics, triangulation approaches, iterative integration | Bridges empirical findings and normative reasoning |

| Interdisciplinary Collaboration Structures | Mixed teams, cross-disciplinary supervision, integrated project designs | Facilitates genuine interdisciplinary exchange and expertise sharing |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Consensus standards, road map criteria, reporting guidelines | Ensures methodological rigor across all research phases |

Each component addresses specific methodological challenges in empirical bioethics. For example, integration methodologies specifically target the fundamental "is-ought" challenge by providing systematic approaches to combining descriptive and normative elements [10] [11]. The toolkit metaphor emphasizes that successful research requires selecting appropriate methodological "reagents" for the specific research question at hand, much as laboratory scientists select appropriate physical reagents for their experiments.

This comparison of frameworks demonstrates significant progress in establishing methodological standards for empirical bioethics research. The consensus-based 15-standards approach and the reflective road map criteria represent complementary strategies for enhancing quality—the former providing specific benchmarks, the latter offering heuristic guidance for research planning and execution. Quantitative evidence shows that evaluative empirical research constitutes a substantial minority (36%) of current empirical bioethics publications, indicating growing attention to how ethical recommendations translate into practice [14].

The distinction between formal, cognitive, and ethical norms provides a valuable conceptual framework for understanding different dimensions of quality in interdisciplinary bioethics research. By adopting these emerging standards and frameworks, researchers can address fundamental challenges to the field's credibility while enhancing the practical impact and scholarly excellence of their work. Future methodological development should focus on validating and refining these criteria across diverse research contexts while maintaining the productive tension between empirical and normative approaches that defines this innovative field.

Empirical bioethics is navigating a critical juncture in its development as a field. Born from the necessity to address complex societal challenges posed by advances in life sciences and biotechnology, bioethics has increasingly embraced interdisciplinary approaches over the past quarter-century [15]. This evolution from traditional single-discipline methodologies toward integrative frameworks represents a fundamental shift in how bioethical inquiry is structured and validated. The growing recognition that ethical decision-making in healthcare requires multiple perspectives has fueled this transformation, moving the field beyond the limitations of traditional disciplinary boundaries [3].

The central challenge facing contemporary bioethics lies in establishing itself as a distinct community of practice while navigating its inherently interdisciplinary nature. Disciplines are characterized partly by their methods and standards of rigor, but when bioethics research draws on diverse methods from philosophy, law, medicine, theology, sociology, and other fields, determining what constitutes rigor becomes complex [3]. This methodological pluralism has led to significant disagreement about bioethics' disciplinary status—variously described as a discipline, applied discipline, multidisciplinary endeavor, interdisciplinary field, or simply a field of study [3]. This terminology debate reflects deeper uncertainties about the methods and standards that should govern bioethical inquiry and how various disciplinary perspectives can be integrated to produce valid, reliable normative conclusions.

Comparative Analysis of Interdisciplinary Approaches

The bioethics landscape encompasses several distinct models of interdisciplinary practice, each with characteristic methodologies, strengths, and limitations. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these primary approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Interdisciplinary Approaches in Bioethics

| Approach | Definition | Key Characteristics | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Interdisciplinarity | Exemplified by the Nuffield Council, focuses on autonomous ethical inquiry and problematizing foundational assumptions [15] | Develops public-facing "non-expert discourse of experts"; emphasizes situated reflection [15] | Challenges disciplinary biases; fosters novel insights | Difficulties deriving positive normative conclusions; challenges generalizing from situated contexts [15] |

| Integrated Empirical Bioethics | Systematic integration of empirical social scientific analysis with ethical analysis to draw normative conclusions [2] | Explicit methodology for combining empirical and normative elements; transparent about integration process [2] | Grounds normative conclusions in empirical reality; enhances practical relevance | Faces "is-ought" challenge; requires sophisticated methodological expertise [2] |

| Multidisciplinary | Multiple disciplines work side-by-side without significant integration [3] | Additive rather than integrative; maintains disciplinary boundaries | Respects disciplinary standards; easier to evaluate by traditional criteria | Limited synthesis; potential for fragmented conclusions [3] |

| Anticipatory Bioethics | Focuses on ethical analysis of emerging technologies before widespread implementation [16] | Future-oriented; attempts to inform technology development proactively [16] | Potential for practical impact before technological lock-in; addresses timing challenges | Risk of speculation; limited empirical evidence for validation [16] |

Methodological Rigor: Protocols and Standards

Consensus Standards for Empirical Bioethics Research

A significant development in establishing methodological rigor is the emergence of consensus standards for empirical bioethics research. Through a modified Delphi process involving 16 academics from five European countries, researchers have identified 15 standards of practice organized into six domains [2]. These standards provide a framework for ensuring quality and rigor in interdisciplinary bioethics research.

Table 2: Domains and Standards for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Domain | Key Standards | Practical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Aims | Clear statement of research aims and purpose of empirical component [2] | Explicit justification for interdisciplinary approach; definition of target outcomes |

| Questions | Formulation of research questions requiring both empirical and normative analysis [2] | Questions that cannot be adequately addressed within single disciplines |

| Integration | Transparent description of how empirical and normative elements are connected [2] | Methodological clarity about integration process; justification for chosen approach |

| Conduct of Empirical Work | Appropriate application of social science methods; reflection on limitations [2] | Rigorous data collection and analysis; awareness of disciplinary norms |

| Conduct of Normative Work | Transparent normative framework; clear justification for normative claims [2] | Philosophical rigor; acknowledgement of value premises |

| Training & Expertise | Research team possesses appropriate combination of empirical and normative expertise [2] | Collaborative teams with complementary skills; interdisciplinary training |

Experimental Protocols for Interdisciplinary Integration

Several specific methodological protocols have been developed to facilitate rigorous integration of disciplinary perspectives in bioethics research:

The Dialogue Method: This approach structures facilitated discussions between stakeholders from different disciplinary backgrounds, creating what has been described as "akin to a philosophy seminar" [2]. The protocol involves: (1) identification of relevant disciplinary perspectives and stakeholders; (2) structured dialogue sessions with explicit methodological rules; (3) iterative development of ethical frameworks; (4) validation through application to specific cases. This method transforms standard data collection techniques like focus groups into more interrogative and challenging forums suitable for ethical analysis.

Systematic Integration Methodology: Developed to address the challenge of deriving normative conclusions from empirical data, this protocol includes: (1) parallel empirical and normative analysis; (2) identification of points of convergence and divergence; (3) development of integrated conclusions through iterative reflection; (4) transparency about limitations in the integration process [2]. This methodology explicitly addresses the "is-ought" challenge that often troubles interdisciplinary bioethics research.

Validation Framework for Anticipatory Bioethics: Specifically designed for analyzing emerging technologies, this protocol involves: (1) explicit clarification of implicit assumptions; (2) validation of assumptions through evidence from interdisciplinary scholarly literature; (3) broad perspective analysis to contextualize findings; (4) systematic assessment of potential impacts and ethical implications [16]. This framework aims to enhance methodological rigor in future-oriented bioethical analysis.

Visualization of Interdisciplinary Processes

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and workflow for interdisciplinary integration in bioethics research, mapping the relationship between different elements and processes:

Successful interdisciplinary work in bioethics requires specific methodological resources and competencies. The table below outlines essential components of the interdisciplinary bioethics toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Methodological Resources for Interdisciplinary Bioethics

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical Methods | Qualitative interviews, focus groups, surveys, ethnographic observation [2] | Generate data about stakeholder perspectives, practices, and contexts |

| Normative Analysis Frameworks | Principle-based approaches, casuistry, virtue ethics, consequentialist analysis [2] | Provide structured methods for ethical analysis and justification |

| Integration Methodologies | Dialogical methods, reflective equilibrium, embedded research models [2] | Facilitate combination of empirical and normative elements |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Consensus standards, peer review protocols, validation frameworks [2] | Ensure methodological rigor and appropriate application of methods |

| Interdisciplinary Communication Aids | Conceptual clarification protocols, terminology guides [17] | Bridge disciplinary language and conceptual differences |

Institutional Models and Global Variations

Exemplary Institutional Approaches

Several institutions have developed distinctive models for fostering interdisciplinary bioethics practice:

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics exemplifies the model of critical interdisciplinarity, emphasizing autonomous ethical inquiry that problematizes foundational assumptions rather than taking them as given [15]. This approach has developed a public-facing "non-expert discourse of experts" that makes complex ethical discussions accessible while maintaining scholarly rigor. The Council's methodology involves situating ethical reflection in specific contexts while grappling with the challenge of deriving positive normative conclusions from this situated approach [15].

Yale Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics adopts a comprehensive approach that extends beyond biomedical ethics to include environmental ethics, animal ethics, scientific research ethics, business ethics, and emerging technologies [18]. Their model combines academic research with practical engagement through institutional review boards and hospital ethics committees, creating bridges between theoretical reflection and practical application.

University of Toronto's Interdisciplinary Bioethics Working Group brings together healthcare practitioners, academic philosophers, clinical ethicists, students, and resident physicians to address fundamental questions about what "doing bioethics" means across different professional contexts [17]. This model explicitly tackles communication gaps between groups with different assumptions about bioethics' purpose and methods.

Global Variations in Ethical Review Processes

The institutionalization of bioethics is reflected in global variations in research ethics review processes. A recent study of 17 countries revealed significant heterogeneity in ethical approval requirements and timelines, illustrating how interdisciplinary bioethics interfaces with regulatory frameworks [7]. For example, while European countries like Belgium and the UK have processes described as particularly arduous (often exceeding six months for interventional studies), countries like Vietnam and Hong Kong have streamlined mechanisms for certain study types [7]. These variations present both challenges and opportunities for interdisciplinary bioethics operating in international contexts.

Challenges and Future Directions

Persistent Methodological Challenges

Despite progress in developing interdisciplinary methodologies, bioethics continues to face several persistent challenges:

The Rigor Challenge: The absence of clear, universally accepted standards for answering bioethical questions remains problematic [3]. With researchers from different disciplinary backgrounds applying different methods and having different goals, determining how to assess normative conclusions is complex. This challenge affects practical decision-making in clinical settings, where integrating various disciplinary perspectives continues to be difficult [3].

The Legitimacy Challenge: The lack of clarity regarding disciplinary status and standards of rigor undermines bioethics researchers' "claims to authority, credibility and legitimacy" [3]. Without agreed-upon criteria for determining valid knowledge, the field's influence on policy and practice may be limited.

The Integration Challenge: Effectively integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives remains methodologically difficult. Each discipline brings its own standards of rigor, methodological approaches, and epistemological assumptions, creating challenges for generating coherent, defensible conclusions [3].

Future Directions for Interdisciplinary Bioethics

The future development of bioethics as a distinct community of practice will likely focus on several key areas:

Methodological Consolidation: There is growing momentum toward developing more precise methodological standards for interdisciplinary work, particularly regarding how empirical and normative elements should be integrated [2]. This includes clearer frameworks for validating interdisciplinary approaches and assessing the quality of resulting research.

Enhanced Training Models: As the field matures, developing more sophisticated training approaches that equip researchers with both empirical and normative competencies becomes increasingly important [2]. This includes creating pathways for developing "dual expertise" or fostering more effective collaborative models.

Global Engagement: Bioethics is increasingly developing frameworks for globally resonant ethics that can guide powerful scientific developments while respecting cultural and contextual variations [15]. This involves navigating tensions between universal ethical principles and culturally situated values.

Anticipatory Methodology: There is growing emphasis on strengthening methodological rigor in anticipatory bioethics to distinguish it from mere speculation while maintaining its future-oriented, proactive character [16]. This includes developing better evidence-based approaches to analyzing emerging technologies.

Interdisciplinarity has transformed bioethics from a theoretical subfield into a distinct community of practice with its own methodological approaches, standards of rigor, and institutional structures. While challenges remain in fully integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives and establishing universally accepted standards of quality, the field has made significant progress in developing frameworks for rigorous interdisciplinary inquiry. The consolidation of methodological standards, exemplified by the consensus around empirical bioethics practices, represents a crucial step in bioethics' maturation as a field capable of addressing complex ethical challenges in healthcare and biotechnology.

As bioethics continues to evolve, its future as a distinct community of practice will depend on maintaining its commitment to methodological rigor while remaining adaptable to new challenges and responsive to the needs of multiple stakeholders. By embracing its interdisciplinary character while continuing to develop its unique methodological identity, bioethics can strengthen its contribution to both scholarly discourse and practical decision-making in increasingly complex biomedical contexts.

Implementing Methodological Frameworks: From Theory to Practice

In the rigorous field of bioethics, the selection of appropriate research methodologies is paramount for generating robust, credible, and actionable knowledge. The scholarly landscape is broadly divided into two methodological paradigms: empirical research, which is grounded in observed and measured phenomena, and non-empirical research, which derives knowledge from theoretical analysis, argumentation, and the synthesis of existing work [19] [20]. Empirical research answers questions about "how the world is" through direct experience, relying on concrete, verifiable evidence gathered via observation or experimentation [19]. Its origins trace back to ancient Greek practitioners who shifted from dogmatic principles to dependence on observed phenomena, with the term "empirical" stemming from the Greek "empeirikos," meaning "experienced" [19].

Conversely, non-empirical research does not involve the firsthand collection of data [20]. Instead, it analyzes and summarizes existing research, theories, and beliefs to advance conceptual understanding, critique ethical frameworks, or develop normative positions. In bioethics, this often takes the form of philosophical inquiry, theoretical essays, and literature reviews. The tension and potential for synergy between these approaches form a central theme in contemporary bioethics, raising critical questions about how the "is" of empirical observation can inform the "ought" of normative ethics [4]. This guide provides a structured comparison of these approaches, offering researchers a framework for assessing methodological rigor and selecting the optimal path for their investigative objectives.

Comparative Analysis: Core Characteristics and Applications

Empirical Research: Measurement and Observation

Empirical research is defined by its exclusive derivation of conclusions from concrete, verifiable evidence [19]. It functions to create new knowledge about the way the world actually works by systematically investigating a particular problem using methodologies rooted in the social or natural sciences [21]. A key hallmark of an empirical study is that it presents a new set of findings from original data collection, and its methodology is described in such detail that the study could be recreated and its results tested [20].

Empirical studies in bioethics have seen a statistically significant increase over recent decades, rising from 5.4% of bioethics publications in 1990 to 15.4% in 2003, a trend that is expected to continue [21]. This growth underscores the field's growing recognition of the value of evidence-based inquiry. Empirical research can be categorized hierarchically by its objectives, ranging from foundational descriptive work to studies that aspire to change ethical norms [4].

Table 1: Hierarchical Categories of Empirical Research in Bioethics

| Category | Primary Objective | Exemplary Research Questions | Bioethics Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lay of the Land | To define current practices, opinions, or beliefs; describes the status quo [4]. | What do physicians think about X? How do patients perceive Y? [4] | Surveying the composition and procedures of hospital ethics committees [4]. |

| Ideal vs. Reality | To assess the extent to which actual clinical practice reflects established ethical ideals [4]. | Does reality match our ethical norms? Where are the gaps? | Investigating disparities in healthcare delivery across racial or socioeconomic groups [4]. |

| Improving Care | To develop and test interventions that bring clinical practice closer to ethical ideals [4]. | How can we improve care to align with ethical norms? | Designing and evaluating a new informed consent process to enhance patient comprehension [4]. |

| Changing Ethical Norms | To synthesize empirical data from multiple studies to inform, refine, or challenge existing ethical principles [4]. | Should our ethical norms change based on accumulated evidence? | Using long-term quality of life data from patients with chronic illnesses to reconceptualize "benefit" in end-of-life decisions [4]. |

Non-Empirical Research: Theory and Synthesis

Non-empirical research serves as the backbone of theoretical and conceptual development in bioethics. It is characterized by the analysis, interpretation, and synthesis of existing knowledge, rather than the generation of new, primary data [20]. This approach is indispensable for clarifying concepts, constructing ethical arguments, critiquing underlying assumptions, and providing comprehensive overviews of a field.

Common outputs of non-empirical research include theoretical articles, conceptual analyses, literature reviews, and position papers. These works are typically structured around logical argumentation and the critical engagement with existing literature and philosophical traditions. A key characteristic is the absence of sections such as "Methods (and Materials)" or "Results," as the author(s) did not conduct original research [20]. Instead, they bring together relevant, useful articles on a general topic to provide a synthesized perspective [20].

In bioethics, non-empirical research addresses fundamental questions of value, principle, and justification that are not always amenable to empirical measurement. It provides the normative framework—the "ought"—that guides ethical deliberation and policy formation.

Direct Comparison of Methodological Features

The choice between empirical and non-empirical methods shapes every aspect of a research project, from its initial design to the nature of its conclusions. The table below provides a point-by-point comparison of their defining features.

Table 2: Feature Comparison of Empirical and Non-Empirical Research

| Feature | Empirical Research | Non-Empirical Research |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Knowledge | Actual experience, observation, and measurement [19] [20] | Theory, belief, and logical analysis [20] |

| Primary Output | New, primary data and findings [20] | Synthesis, critique, or theoretical development based on existing work [20] |

| Data Form | Numerical (quantitative) or textual/visual (qualitative) data collected firsthand [19] | Existing texts, theories, and published literature |

| Common Formats | Journal articles with IMRaD structure; studies using surveys, experiments, interviews [20] | Theoretical articles, literature reviews, essays, critical commentaries [20] |

| Research Question | Often "what," "how many," "how," or "why" (exploratory) questions | Often "should," "what ought," or conceptual "what is the meaning of" questions |

| Role in Bioethics | Describes reality, identifies ethical problems in practice, tests feasibility of norms, informs policy with evidence [22] [4] | Develops and justifies moral principles, provides normative recommendations, clarifies concepts, synthesizes fields [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis in Empirical Research

Qualitative Empirical Methodologies

Qualitative research methods are utilized for gathering non-numerical data to determine underlying reasons, views, or meanings from study participants [19]. This approach is more descriptive and is particularly useful for exploring complex concepts, social interactions, and cultural phenomena [23]. It allows researchers to gain a better understanding of "how" or "why" things occur [23].

- Interview Method: This is a widely used conversational approach where in-depth data is obtained through structured, semi-structured, or unstructured formats [19] [23]. It is exclusively qualitative and allows researchers to obtain precise, relevant information by asking the correct questions. Interviews are commonly used in the social sciences and humanities, such as for interviewing resource persons on bioethical issues [19].

- Focus Groups: A focus group is a thoroughly planned discussion guided by a moderator and designed to derive opinions on a designated topic [19]. This method, essentially a group interview, is valuable for thinking through particular issues or concerns and is widely used to answer "how," "what," and "why" questions [19]. In applied settings, focus groups are frequently employed by consumer product producers for designing and improving products based on user preferences.

- Case Study: This method is used to identify extensive information through an in-depth analysis of existing cases [19]. It is typically used to obtain empirical evidence for investigating complex problems in business studies or bioethics. When conducting case studies, the researcher must carefully perform the empirical analysis, ensuring the variables and parameters in the current case are similar to the case being examined.

- Observational Method: This involves observing and gathering data from study subjects in a personal and time-intensive manner [19]. It is often used in ethnographic studies to obtain empirical evidence and is part of the ethnographic research design. While commonly used for qualitative purposes, observation can also be utilized for quantitative research when observing measurable variables.

Quantitative Empirical Methodologies

Quantitative research methods gather numerical data that can be ranked, measured, or categorized through statistical analysis [19] [23]. This approach is useful for uncovering patterns or relationships, making generalizations, and determining how many, how much, how often, or to what extent a phenomenon occurs [23].

- Survey Research: Survey research is designed to generate statistical data about a target audience and can involve large, medium, or small populations [19]. This quantitative method uses predetermined sets of closed questions that are easy to answer, thus enabling the gathering and analysis of large data sets. While traditionally expensive and time-consuming, advancements in technology have made surveys easier and cheaper to administer through email and social media [19].

- Experimental Research: Experiments involve testing hypotheses in controlled conditions by manipulating variables [23]. This method helps determine cause-and-effect relationships and testing outcomes when variables are altered or removed. Traditionally laboratory-based, experimental research is used to advance knowledge in the physical and life sciences, and increasingly in social sciences [19] [23].

- Causal-Comparative Research: This method leverages the strength of comparison to determine cause-and-effect relationships among variables where manipulation is not possible [19]. For example, a causal-comparative study might measure the productivity of employees in an organization that allows remote work compared to staff in an organization that does not offer work-from-home arrangements.

- Longitudinal Study: A longitudinal method researches the traits or behavior of a subject under observation after repeatedly testing over a certain period [19]. Data collected can be qualitative or quantitative. A prominent example is the British Doctors Study initiated in 1951, which compared smokers and non-smokers and provided undeniable proof of the direct link between smoking and lung cancer by 1956 [19].

Data Analysis Techniques

Data analysis methods vary significantly between qualitative and quantitative research, each requiring specific analytical approaches and tools.

Table 3: Data Analysis Methods in Empirical Research

| Method Type | Data Analysis Approach | Common Tools & Techniques | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Analysis | Statistical analysis of numerical data [23] | Descriptive statistics (mean, median, mode, SD) [24]; Inferential statistics (hypothesis testing) [24] | Statistical significance, p-values, correlations, generalizable findings [23] |

| Qualitative Analysis | Interpretive analysis of non-numerical data [23] | Thematic analysis, textual analysis, coding, searching for patterns [19] [25] | Themes, insights, descriptions of multiple realities, conceptual understanding [25] |

For quantitative data, descriptive statistics summarize or describe the characteristics of a dataset, including measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode) and variability (range, standard deviation) [24]. Inferential statistics are used to test research hypotheses and make inferences or predictions about a population based on sample data, involving objective criteria to decide whether a hypothesis should be accepted or rejected [24].

For qualitative data, analysis tends to be more creative, iterative, and holistic [25]. Techniques like thematic analysis involve searching for recurring themes and patterns across qualitative datasets, while textual analysis involves describing, interpreting, and understanding textual content by connecting it to broader artistic, cultural, political, or social contexts [19].

Empirical Research Methodology Selection and Analysis Pathways

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Conducting rigorous research in bioethics requires both conceptual and practical tools. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" and essential materials used across different methodological approaches.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Interview Protocol | Ensures consistency in qualitative data collection by using predetermined questions [23]. | Qualitative studies seeking in-depth personal perspectives on ethical dilemmas. |

| Validated Survey Instrument | Provides reliable and consistent measurement of constructs across a sample population [25]. | Quantitative studies measuring attitudes, beliefs, or practices regarding bioethical issues. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., SAS, R) | Performs descriptive and inferential statistical analyses on numerical data [21] [24]. | Quantitative empirical research for data management, hypothesis testing, and determining significance. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo) | Facilitates coding, thematic analysis, and management of non-numerical data [25]. | Qualitative studies handling large volumes of interview transcripts, field notes, or documents. |

| Ethics Committee Approval | Provides formal ethical oversight and ensures participant protection in research [26]. | All empirical research involving human subjects, ensuring adherence to autonomy, beneficence, justice. |

| Theoretical Framework | Provides a structured conceptual foundation for analyzing ethical problems [22]. | Non-empirical research developing normative arguments or synthesizing ethical concepts. |

| Systematic Literature Search Protocol | Ensures comprehensive, unbiased identification of relevant existing literature [22]. | Literature reviews and non-empirical research requiring thorough knowledge of existing scholarship. |

The selection between empirical and non-empirical approaches is not a matter of choosing a superior methodology, but rather of aligning research methods with specific investigative goals. As this guide demonstrates, each approach offers distinct strengths and addresses different types of research questions within bioethics.

Empirical methods excel at describing realities, identifying ethical issues in practice, and testing the feasibility and consequences of ethical norms [22] [4]. They provide the essential evidence base for understanding how ethical principles manifest in real-world contexts. Non-empirical methods, particularly philosophical and theoretical analysis, remain crucial for developing and justifying moral principles, providing normative recommendations, and engaging in conceptual clarification [22].

The most contested, yet potentially most fruitful, applications of empirical research in bioethics occur at the intersection of "is" and "ought," where empirical findings inform, and sometimes challenge, existing ethical norms [22] [4]. The hierarchical model presented in this guide—from Lay of the Land to Changing Ethical Norms—provides a framework for understanding the potential scope and ambitions of empirical work [4].

For researchers in bioethics and drug development, methodological rigor requires careful consideration of the research question, appropriate selection from the methodological toolkit, and transparent reporting of methods and limitations. Whether through systematic data collection or rigorous philosophical analysis, the ultimate goal remains the same: to produce knowledge that enhances ethical understanding and improves human health and wellbeing.

The integration of social science methods with ethical analysis, a field often termed empirical bioethics, represents a growing and methodologically innovative area of research. This interdisciplinary approach seeks to ground normative ethical conclusions in robust empirical evidence concerning stakeholder values, lived experiences, and social contexts. However, the combination of these distinct paradigms—the empirical "is" and the normative "ought"—presents significant challenges for establishing methodological rigor [3]. The field has been characterized by a "systematic lack of clarity" regarding its primary methods and standards of rigor, which in turn creates challenges for peer review, undermines claims to authority, and complicates practical decision-making [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of predominant structured integration techniques, assessing their protocols, applications, and methodological rigor to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in this complex interdisciplinary space.

Comparative Analysis of Integration Methodologies

The following structured techniques represent the most clearly articulated approaches to integrating social science with ethical analysis, each offering distinct pathways to methodological rigor.

Table 1: Structured Integration Techniques in Empirical Bioethics

| Methodology | Core Integration Mechanism | Primary Applications | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured Ethics Appendix [27] | A predefined set of prompts guiding ethical reflection throughout research, reported in an appendix. | Social science experiments, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), primary data collection. | Promotes transparency, sparks reflective practice, improves communication of ethical considerations. | Can be treated as a bureaucratic checklist rather than a reflective process; relatively new approach. |