Bridging the Is-Ought Gap: Methodologies and Applications in Empirical Bioethics Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for biomedical researchers and professionals on navigating the is-ought gap in empirical bioethics.

Bridging the Is-Ought Gap: Methodologies and Applications in Empirical Bioethics Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for biomedical researchers and professionals on navigating the is-ought gap in empirical bioethics. It explores the foundational debate surrounding Hume's Law, presents practical methodological frameworks for integrating empirical data with normative analysis, addresses common implementation challenges, and validates approaches based on current researcher consensus. By synthesizing theoretical insights with applied strategies, this resource aims to empower interdisciplinary teams in drug development and clinical research to conduct ethically robust and methodologically sound empirical bioethics research.

Demystifying Hume's Law: The Foundation of the Is-Ought Problem in Bioethics

Understanding Hume's Law and its Historical Influence on Bioethics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Hume's Law or the Is-Ought Problem? Hume's Law, also known as the Is-Ought Problem, is the thesis that an ethical or judgmental conclusion (a statement about what ought to be) cannot be logically inferred from purely descriptive, factual statements (statements about what is) [1]. David Hume argued that authors often make this transition imperceptibly and that this new relation of "ought" needs to be observed and explained, as it cannot be a simple deduction from entirely different relations [1].

2. Is Hume's Law a valid argument against empirical bioethics? No, current scholarship argues that Hume's Law is not a definitive argument against empirical bioethics [2] [3]. The interpretation of Hume's Law as creating an unbridgeable logical gulf between facts and morality is dependent on a specific, non-cognitivist meta-ethical stance. Other interpretations are possible, and conflating meta-ethics with applied ethics is problematic [2]. A non-cognitivist interpretation challenges not just empirical bioethics, but all bioethics situated within ethical cognitivism [2].

3. What is the difference between Hume's Law, the fact-value distinction, and the naturalistic fallacy? These are three distinct but often conflated concepts [2]:

- Hume's Law: Concerns the logical relationship between descriptive ("is") and prescriptive ("ought") statements.

- Naturalistic Fallacy: An expression introduced by G.E. Moore to refute ethical naturalism, broadly meaning it is a logical fallacy to define "good" in terms of natural properties [2].

- Fact-Value Distinction: The view that factual statements and value statements are distinct, sometimes extended to the positivist idea that science is value-free [2].

4. How can empirical research be integrated into normative bioethics? Integration is possible through shared meta-ethical postulates. The "bridge postulate" states that a bridge between facts and values is both possible and foundational to bioethics, though its exact nature remains open for discussion. The "ethical cognitivism" postulate states that bioethics generally operates on the assumption that ethical statements are truth-apt and that knowledge is possible in ethics [2].

5. What was the 'empirical turn' in bioethics? The "empirical turn" refers to a shift in the 1990s where social scientists began confidently contributing to bioethics, outlining how sociological and ethnographic perspectives could benefit the field [4]. This shifted bioethics from a field dominated by philosophical application of principles to a "dynamic, changing, multi-sited field" involving multiple disciplines [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Methodological Issues

Problem: Deriving a normative conclusion directly from an empirical dataset.

- Symptoms: A research conclusion states what should be done based solely on descriptive data (e.g., "Our survey found that 80% of clinicians do X, therefore this is the ethical practice.").

- Solution: Explicitly state the normative premise that links your empirical finding to the ethical conclusion. The reasoning should be: (1) Empirical finding: "80% of clinicians do X"; (2) Normative premise: "Clinical practice Y is ethically good because it aligns with the principle of beneficence"; (3) Therefore, the empirical finding is evaluated against an explicit ethical standard.

Problem: Conflating widespread practice (what "is") with ethical justification (what "ought" to be).

- Symptoms: Justifying an action by stating "it's always been done this way," "it's natural," or "everyone else is doing it" without further ethical reasoning [5].

- Solution: Treat common practices as descriptive starting points for ethical reflection, not as normative conclusions. Use empirical data to inform the context and potential consequences of an action, but evaluate those consequences against explicit ethical principles.

Problem: Confusing Hume's Law with the Naturalistic Fallacy.

- Symptoms: Using the terms "Hume's Law" and "Naturalistic Fallacy" interchangeably in research methodology or literature reviews.

- Solution: Differentiate the concepts clearly. Hume's Law deals with the "is-ought" inference, while the Naturalistic Fallacy, in its original Moorean sense, deals with defining "good" in terms of natural properties. Precise terminology strengthens methodological rigor [2].

Research Reagent Solutions: Conceptual Toolkit

| Item | Function in Empirical Bioethics Research |

|---|---|

| Ethical Principles (e.g., Autonomy, Beneficence) | Provide the necessary normative premises for building a bridge from empirical facts ("is") to ethical conclusions ("ought") [4]. |

| Empirical Methods (e.g., surveys, ethnography) | Generate the descriptive, factual data ("is") about human behavior, beliefs, and contexts in healthcare and the life sciences [4]. |

| Bridge Postulate | Serves as the foundational meta-ethical assumption that a connection between facts and values is possible, justifying the entire empirical-normative research enterprise [2]. |

| Ethical Cognitivism Postulate | Provides the underlying assumption that ethical statements can be truth-apt, making rational discourse and knowledge in bioethics possible [2]. |

| Interdisciplinary Dialogue | The methodological framework that allows empirical data and normative analysis to inform and refine each other, creating a coherent justification for conclusions. |

Experimental Protocol: Bridging the Is-Ought Gap

This protocol provides a structured methodology for integrating empirical findings with normative analysis, creating a justified bridge across the is-ought gap.

1. Problem Identification & Literature Review

- Identify a specific ethical dilemma in biomedicine or research (e.g., informed consent for a new genetic therapy).

- Conduct a systematic review of both (a) relevant empirical literature (e.g., studies on patient comprehension of genetic information) and (b) relevant normative literature (e.g., ethical analyses of autonomy and consent).

2. Empirical Data Collection & Analysis

- Objective: To gather robust descriptive data ("is") related to the identified problem.

- Methodology Selection: Choose an appropriate empirical method (e.g., qualitative interviews with stakeholders, quantitative surveys, observational ethnography).

- Execution: Collect and analyze data according to the standards of the chosen methodological discipline (e.g., thematic analysis for interviews, statistical analysis for surveys).

3. Normative Analysis & Premise Articulation

- Objective: To make explicit the ethical values and principles ("ought") relevant to the problem.

- Methodology: Conduct a philosophical analysis to identify and justify the key ethical principles at stake (e.g., respect for persons, justice, well-being). This step involves articulating the normative premises that are often left unstated.

4. Integrative Synthesis

- Objective: To logically connect the empirical findings with the normative framework.

- Methodology: Do not present data and ethics as separate sections. Instead, synthesize them. For example: "Our empirical finding (F) interacts with ethical principle (P) in the following way... Therefore, to uphold principle (P) in light of finding (F), we ought to consider action (A)." This creates a coherent argument where the "ought" is derived from the normative principle, informed and shaped by the empirical facts.

5. Conclusion & Recommendation Formulation

- Formulate specific, actionable recommendations that are logically supported by the integrative synthesis. The conclusion should be a prescriptive statement that is transparently justified by both the empirical evidence and the articulated normative premises.

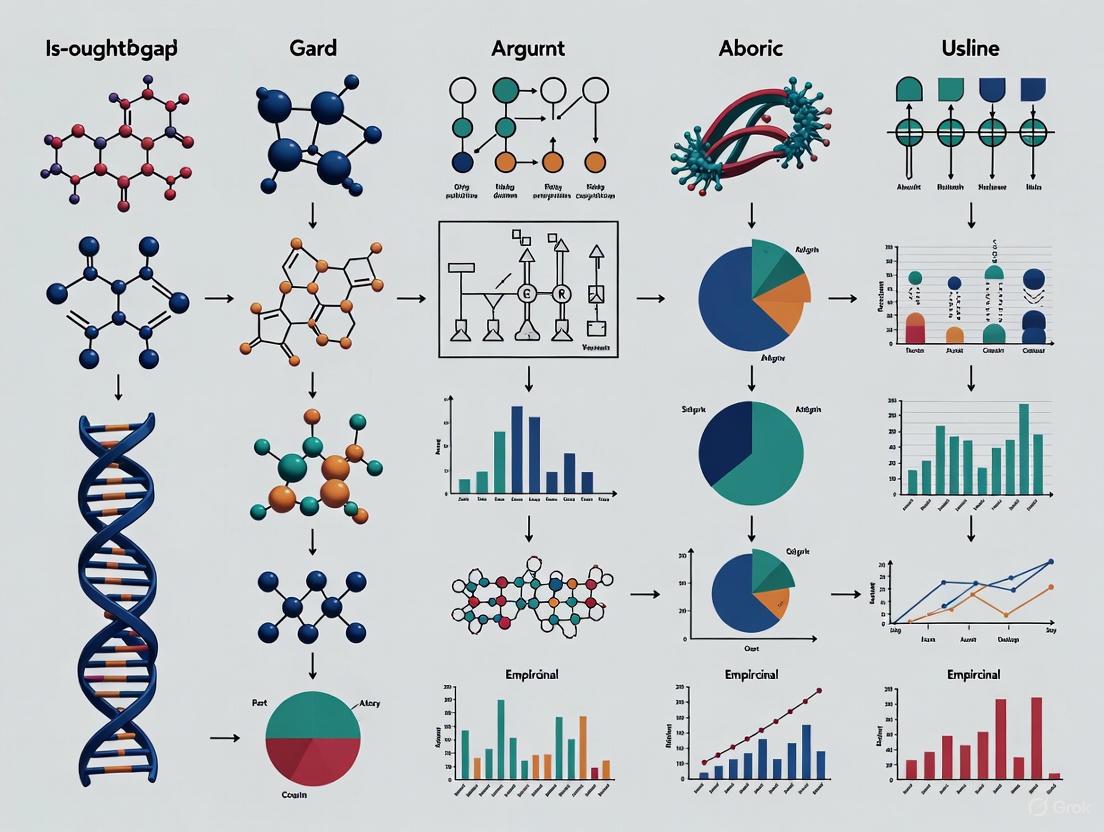

Workflow Diagram

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Meta-Ethical Concepts in Empirical Bioethics

This guide helps researchers navigate common conceptual errors when integrating empirical data with normative reasoning. Correctly distinguishing these ideas is foundational to robust and defensible empirical bioethics research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My empirical data describes what is happening in practice, but reviewers say I cannot conclude what we ought to do.

- Potential Cause: Attempting to directly derive a normative conclusion from purely descriptive premises, which invokes the Is-Ought Problem [1] [2].

- Solution:

- Explicitly state your normative premise. All ethical argumentation requires at least one foundational value judgment [1] [2]. For example: "If a practice causes demonstrable harm to patient well-being (empirical claim), and if we ought to prevent patient harm (normative premise), then we ought to change this practice."

- Use empirical data to test normative assumptions. Data cannot generate an "ought" from nothing, but it can test the feasibility, consequences, and real-world application of existing ethical principles [6] [7].

- Reframe your conclusion. Instead of making a sweeping normative statement, position your finding as identifying an ethical issue, informing the context of a debate, or testing how a known norm functions in practice [6].

Problem: A colleague claims that because a behavior is "natural" or biological, it is therefore ethically justified.

- Potential Cause: Committing the Naturalistic Fallacy, which is the error of defining "good" solely in terms of natural properties or of equating what is natural with what is good [8] [9].

- Solution:

- Challenge the definition. Question whether "natural" is being clearly defined and whether that definition logically entails "good." G.E. Moore's Open-Question Argument is useful here: "Yes, this trait evolved, but is it good?" The very possibility of this question shows the terms are not equivalent [1] [9].

- Provide counterexamples. Identify clear cases where a natural fact (e.g., a disease) is not considered good, or a valued thing (e.g., a vaccine) is not strictly "natural."

- Separate description from evaluation. Clearly differentiate the empirical claim ("This behavior occurs in nature") from the separate, required value judgment ("This behavior is morally desirable") [5].

Problem: My team cannot agree on whether a study finding is an objective fact or a value-laden observation.

- Potential Cause: Confusion around the Fact-Value Distinction, which holds that statements about what is the case (descriptive) are logically different from statements about what ought to be the case (evaluative/prescriptive) [10] [9].

- Solution:

- Perform a language test. Look for value-laden words like "good," "bad," "should," "unjust," or "harmful." Their presence often signals an evaluative claim [9].

- Apply the distinction pragmatically. While some philosophers argue for a strict dichotomy, for practical research purposes, treat it as a warning to be critically aware of when you are reporting data versus when you are interpreting it through a moral framework [2] [10].

- Document the transition. In your research write-up, make a clear and justified connection between the factual evidence you present and the value-based interpretation or recommendation you make [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Are the Is-Ought Problem and the Naturalistic Fallacy the same thing? A1: No, they are distinct but related concepts. The Is-Ought Problem, identified by David Hume, is a broader logical challenge about the validity of inferring prescriptive statements ("ought") from descriptive statements ("is") [1] [2]. The Naturalistic Fallacy, coined by G.E. Moore, is a specific instance of this problem where one incorrectly defines "good" in terms of some natural property (like "pleasurable" or "evolutionarily successful") [2] [8] [9]. All instances of the naturalistic fallacy violate the is-ought rule, but not all is-ought violations are naturalistic fallacies.

Q2: How can the Fact-Value Distinction be a problem for scientific research? A2: A strict interpretation of the distinction suggests that science, which deals in empirical facts, is fundamentally separate from ethics and values [10]. This would seem to invalidate the project of empirical bioethics from the start. However, most contemporary approaches reject a rigid dichotomy. Instead, they recognize that while facts and values are different, they are deeply intertwined in practice. Values influence what research questions we ask, how we interpret data, and what we deem a "good" outcome, while facts are essential for understanding the real-world implications of our values [2] [10] [9].

Q3: If we can't derive an "ought" from an "is," how can empirical research possibly inform bioethics? A3: This is the central challenge for empirical bioethics. The solution is not to attempt a direct, logical derivation but to use empirical data in more nuanced ways. Researchers report that data is most useful for:

- Understanding context and identifying ethical issues in practice [6].

- Testing the feasibility and consequences of ethical norms [6] [7].

- Informing the specification of general principles [7]. The "is-ought gap" thus acts not as a barrier, but as a critical warning to reflect carefully on how we integrate facts with our value judgments [2] [6].

Conceptual Comparison Table

The table below summarizes the core differences and relationships between these three key concepts.

| Concept | Core Definition | Primary Proponent | Key Question | Role in Empirical Bioethics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is-Ought Problem [1] [2] | The logical challenge of deriving prescriptive conclusions ("ought") from purely descriptive premises ("is"). | David Hume | How can a statement about what should be validly inferred from statements about what is? | A foundational logical rule warning against unjustified leaps from data to policy. |

| Fact-Value Distinction [10] [9] | An epistemological distinction between statements of fact (descriptive, based on observation) and statements of value (prescriptive, based on ethics/aesthetics). | Derived from Hume; emphasized by Max Weber | How do claims about the world (facts) differ from claims about what is good or right (values)? | A heuristic to maintain awareness of when a researcher is reporting data versus making a value judgment. |

| Naturalistic Fallacy [8] [9] | The specific error of defining "good" in terms of natural properties or inferring that something is good because it is natural. | G.E. Moore | Can the moral quality "good" be defined without remainder by any set of natural properties? | A common pitfall to avoid, particularly when appealing to biology, evolution, or "human nature" in ethical arguments. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Conceptual Reagents

Just as an experiment requires specific materials, clear reasoning in empirical bioethics requires these conceptual tools.

| Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit Normative Premise | Provides the necessary ethical foundation for an argument, bridging the is-ought gap [1] [2]. | "Given our commitment to justice (normative premise), and data showing this policy disproportionately harms a vulnerable group (empirical fact), we ought to revise the policy." |

| The Open-Question Test | A mental model to detect the naturalistic fallacy by questioning any definition of "good" [9]. | "You say 'good' is 'what is pleasurable.' But is pleasure always good?" The possibility of this question shows the terms are not synonymous. |

| Descriptive/Evaluative Language Filter | A writing and review check to ensure clarity about when a statement is a fact versus a value judgment [9]. | Flagging words like "should," "unjust," or "harmful" in a manuscript and verifying that the shift from descriptive to evaluative is explicitly justified. |

Logical Workflow for Navigating the Is-Ought Gap

The following diagram maps the logical pathway from empirical observation to an ethically robust conclusion, showing where these conceptual distinctions come into play.

Experimental Protocol: Testing a Normative Claim with Empirical Data

This methodology outlines a robust approach for using empirical research to inform, without improperly deriving, ethical conclusions.

Objective: To evaluate how a specific ethical norm (e.g., "patients ought to be fully informed before consent") functions in a real-world clinical context.

Background: The Is-Ought Problem forbids creating a norm from data alone, but data can test a norm's application and consequences [6] [7].

Procedure:

- Normative Specification: Begin with a clear, general ethical principle (e.g., "Respect for persons requires informed consent") [7].

- Operationalization: Define measurable empirical indicators for the norm. For informed consent, this could be:

- Indicator 1: Patient recall of procedural risks.

- Indicator 2: Patient understanding of alternative treatments.

- Indicator 3: Patient perception of coercion.

- Data Collection: Employ mixed methods (e.g., surveys to quantify understanding, in-depth interviews to qualify patient experience) to gather data on these indicators [6].

- Integration & Analysis:

- Compare the empirical findings against the ideal expressed by the norm.

- Identify barriers (e.g., complex medical language, time constraints) that cause the "is" (practice) to diverge from the "ought" (norm) [6] [7].

- Use these findings not to create a new norm, but to specify or refine how the original norm can be better enacted (e.g., "The principle of informed consent necessitates the use of plain-language guides and dedicated consent counselors") [7].

Expected Outcome: The research provides an evidence-based justification for specific practices and policies that uphold a core ethical principle, thereby bridging the "is-ought" gap through specification and application rather than faulty derivation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are Hume's Law and the Is-Ought Problem, and why are they relevant to my empirical bioethics research?

Hume's Law, originating from philosopher David Hume, is the thesis that an ethical or judgmental conclusion (an "ought") cannot be logically inferred from purely descriptive, factual statements (an "is") [1]. This is also known as the Is-Ought Problem. For empirical bioethics, which integrates empirical data with normative analysis, this poses a potential foundational challenge: if "no ought from is," how can bioethics be empirical? [2] However, this is often seen not as an insurmountable barrier, but as a critical warning sign to carefully reflect on the normative implications of empirical results [11].

Q2: Aren't Hume's Law, the fact-value distinction, and the naturalistic fallacy the same thing?

No, this is a common conflation in bioethics literature [2]. They are distinct though interrelated concepts:

- Hume's Law deals with the logical relationship between descriptive ("is") and prescriptive ("ought") statements [2] [1].

- The Naturalistic Fallacy, a term coined by G.E. Moore, is the claim that it is a fallacy to define "good" in terms of natural properties, representing a meta-ethical refutation of ethical naturalism [2].

- The Fact-Value Distinction is the view that facts and values are distinct, sometimes encompassing the idea that science is value-free [2].

Q3: What practical challenges might I face when integrating empirical data with normative analysis?

Researchers often report an "air of uncertainty and overall vagueness" during integration [12]. Key challenges include:

- Methodological Indeterminacy: While many methodologies exist (e.g., reflective equilibrium, dialogical ethics), their practical steps are often unspecific, leading to flexibility but also potential obscurity [12].

- Weighting Evidence: It can be difficult to determine how much weight to give empirical data versus ethical theory during the analytic process [12].

- Ethical Disruption: The research process itself can be disruptive, as it may require participants to critically explore settled moral views, potentially leaving them feeling unsettled or that they are "in the wrong" [13].

Q4: What are the acceptable objectives for conducting empirical research in bioethics?

A qualitative study of bioethics researchers found varying levels of agreement on different objectives [11]. The most and least supported objectives are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Acceptability of Objectives for Empirical Research in Bioethics

| Objective of Empirical Research | Level of Acceptance |

|---|---|

| Understanding the context of a bioethical issue | Unanimous agreement [11]. |

| Identifying ethical issues in practice | Unanimous agreement [11]. |

| Striving to draw normative recommendations | Highly contested [11]. |

| Developing and justifying moral principles | Highly contested [11]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Uncertainty in choosing a methodology for integrating empirical and normative analysis.

Solution: Familiarize yourself with established methodological families. Select a method that aligns with your research question and epistemological stance, and be prepared to justify your choice transparently [12].

Table 2: Methodologies for Integrating Empirical and Normative Analysis

| Methodology | Core Approach | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Reflective Equilibrium [12] | A "back-and-forth" process of adjustment by the researcher. | The researcher ("the thinker") iteratively moves between ethical principles, empirical data, and considered judgments until a state of moral coherence ("equilibrium") is achieved. A consultative model. |

| Dialogical Empirical Ethics [12] | Relies on structured discourse between stakeholders. | Integration occurs through collaboration and dialogue between researchers, participants, and other stakeholders to reach a shared understanding. A dialogical model. |

| Grounded Moral Analysis [12] | Develops normative conclusions directly from empirical data. | The empirical and normative elements are intertwined from the start of the research project, with moral principles being developed or refined through the analysis of data. An inherent integration model. |

Problem: Navigating the Is-Ought gap when deriving normative recommendations from data.

Solution: Do not treat empirical data as a direct source of moral "oughts." Instead, use it to test, refine, and inform the application of normative principles within a specific context [11]. The following workflow, often used in Reflective Equilibrium, visualizes this process.

Problem: My research team has different disciplinary backgrounds, leading to confusion about the role of empirical findings.

Solution: Establish clear objectives and theoretical positioning early in the research process [12]. Use the following chart to clarify how empirical research functions within the broader bioethical inquiry and to identify potential sources of interdisciplinary confusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This toolkit outlines essential conceptual "reagents" for designing and executing a rigorous empirical bioethics study.

Table 3: Essential Conceptual Tools for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Tool Name | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bridge Postulate [2] | Foundational assumption that a connection between facts and values is possible. | A necessary meta-ethical starting point that justifies the entire empirical bioethics endeavor. |

| Ethical Cognitivism Postulate [2] | Assumption that ethical statements can be truth-apt and that ethical knowledge is possible. | Positions your research within a mainstream meta-ethical framework, countering non-cognitivist interpretations of Hume's Law. |

| "Reasonable Person" Standard [14] | A normative benchmark for interpreting empirical data on participant preferences. | Used, for example, to determine what information should be provided during informed consent by referencing what a "reasonable person" would want to know. |

| Transparency in Integration [12] | The practice of explicitly stating and justifying how empirical data and normative analysis are combined. | A crucial standard for methodological rigor. Researchers must clearly explain their chosen method of integration and how it was executed. |

Empirical bioethics faces a fundamental challenge: how can researchers legitimately integrate descriptive statements about what is (facts derived from empirical data) with prescriptive statements about what ought to be (moral values and norms)? This problem, known as the is-ought gap or Hume's Law, presents a significant methodological hurdle [2]. The Bridge Postulate addresses this challenge directly by asserting that a bridge between facts and values is not only possible but foundational to the entire bioethics endeavor [2]. This technical framework provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical methodologies and troubleshooting guidance for implementing this postulate in their experimental research, enabling them to navigate the complex terrain between empirical observation and normative recommendation without committing logical fallacies.

Understanding the Conceptual Framework

Defining the Is-Ought Problem and Its Implications

The is-ought problem, derived from David Hume's philosophical work, highlights the logical distinction between descriptive statements (what "is") and prescriptive statements (what "ought" to be) [2]. In contemporary terminology, this means that no set of purely descriptive statements can entail an evaluative statement without additional evaluative premises [2]. For bioethics researchers, this creates a significant methodological challenge when attempting to derive ethical recommendations from empirical data alone.

Three distinct concepts are often conflated in this discussion but must be carefully distinguished:

- Hume's Law: Concerns the logical relationship between "is" and "ought" statements

- Naturalistic Fallacy: A term introduced by G.E. Moore referring to defining "good" in terms of natural properties

- Fact-Value Distinction: The view that factual statements and value statements have different truth conditions [2]

The Bridge Postulate: Core Principles

The Bridge Postulate rests on two foundational principles that guide empirical bioethics research:

Bridge Possibility Principle: A bridge between facts and values is both possible and foundational to bioethics, though the nature of this bridge remains open to methodological discussion and refinement [2].

Ethical Cognitivism Principle: Unless explicitly stated otherwise, bioethics operates within ethical cognitivism - the view that ethical statements are truth-apt and that knowledge is possible in ethics [2].

These principles enable researchers to proceed with empirical-normative integration while maintaining philosophical rigor, providing a framework for developing methodologies that explicitly address the is-ought challenge rather than ignoring it.

Methodological Framework: Mapping, Framing, Shaping

The Mapping-Framing-Shaping framework provides a structured approach to empirical bioethics research projects, offering a comprehensive methodology for implementing the Bridge Postulate in practice [15].

Phase 1: Mapping the Terrain

The mapping phase involves surveying existing knowledge to understand the current state of research and identify gaps [15].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Literature Mapping

Objective: To comprehensively identify and analyze existing literature, policies, and empirical data relevant to the bioethical issue under investigation.

Methodology:

- Conduct systematic searches across relevant databases (e.g., PubMed, SCOPUS, specialized ethics databases)

- Identify and analyze key concepts, controversies, and consensus positions in the literature

- Map relationships between different stakeholder perspectives and evidence types

- Identify knowledge gaps and methodological limitations in existing research

Technical Requirements:

- Access to comprehensive academic databases

- Reference management software (e.g., EndNote, Zotero)

- Qualitative data analysis software for thematic analysis (e.g., NVivo, Atlas.ti)

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Overwhelming volume of irrelevant literature in search results.

- Solution: Refine search strategy using Boolean operators, field-specific filters, and iterative search techniques.

- Problem: Inconsistent terminology across disciplines.

- Solution: Develop a comprehensive taxonomy of relevant terms and conduct synonym searches.

Phase 2: Framing Stakeholder Perspectives

The framing phase involves in-depth exploration of how stakeholders experience and perceive the ethical issues identified in the mapping phase [15].

Experimental Protocol: Qualitative Stakeholder Framing

Objective: To understand how ethical issues are framed, experienced, and perceived by relevant stakeholders.

Methodology:

- Identify and recruit diverse stakeholders through purposive sampling

- Conduct in-depth interviews, focus groups, or ethnographic observations

- Analyze qualitative data using established techniques (thematic analysis, grounded theory)

- Identify patterns in how stakeholders frame ethical problems and potential solutions

Technical Requirements:

- Interview/focus group guides tailored to different stakeholder groups

- Audio recording equipment and transcription services

- Qualitative data analysis software

- Ethical approval for research involving human participants

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Stakeholders provide socially desirable responses rather than genuine perspectives.

- Solution: Establish rapport, ensure anonymity, use indirect questioning techniques.

- Problem: Conflicting perspectives between different stakeholder groups.

- Solution: Maintain detailed records of contextual factors influencing different perspectives.

Phase 3: Shaping Ethical Recommendations

The shaping phase involves developing normative recommendations informed by the preceding mapping and framing phases [15].

Experimental Protocol: Integrative Ethical Analysis

Objective: To develop ethically justified recommendations that are informed by both empirical evidence and normative analysis.

Methodology:

- Explicitly articulate the method of integration between empirical findings and normative reasoning

- Identify points of convergence and divergence between different evidence sources

- Develop recommendations through reflective equilibrium, balancing principles, evidence, and case judgments

- Specify limitations and conditions for application of recommendations

Technical Requirements:

- Documentation of the entire research process for transparency

- Framework for assessing the strength and quality of different types of evidence

- Method for addressing residual uncertainty and disagreement

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Empirical data appears to conflict with established ethical principles.

- Solution: Re-examine interpretation of data and application of principles; consider mid-level principles to mediate between abstract theory and empirical facts.

- Problem: Difficulty in justifying why certain empirical findings should influence normative conclusions.

- Solution: Explicitly articulate the relevance of specific facts to ethical values through "bridging premises."

The following diagram illustrates the overall workflow and the critical integration points in this methodology:

Research Reagent Solutions: Methodological Tools

Table 1: Essential Methodological Tools for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Techniques | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | Semi-structured interviews | Elicit rich, nuanced stakeholder perspectives | Framing phase: understanding lived experiences |

| Focus groups | Identify group dynamics and shared understandings | Framing phase: exploring collective perspectives | |

| Systematic surveys | Quantify attitudes, beliefs, and preferences | Mapping phase: establishing prevalence of views | |

| Data Analysis | Thematic analysis | Identify, analyze, and report patterns in qualitative data | Framing phase: analyzing interview/focus group data |

| Content analysis | Systematically categorize textual content | Mapping phase: analyzing literature and documents | |

| Ethical matrix | Structure evaluation of options against ethical principles | Shaping phase: comparative ethical analysis | |

| Integration Methods | Reflective equilibrium | Achieve coherence between principles, cases, and judgments | Shaping phase: developing justified recommendations |

| Mid-level principles | Mediate between abstract theory and empirical facts | Shaping phase: bridging theory and practice | |

| Case-based reasoning | Use paradigm cases to inform new situations | Shaping phase: analogical reasoning in ethics |

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Common Challenges

Conceptual and Methodological Challenges

Q: How can we avoid deriving "ought" directly from "is" when making recommendations based on empirical data?

A: The key is to explicitly include normative premises that justify why specific facts are morally relevant. For example, instead of moving directly from "patients prefer X" to "we should do X," include the bridging premise: "patient preferences should be respected in contexts Y and Z, with exceptions A, B, and C." Document these bridging premises transparently in your methodology [2] [11].

Q: What is the difference between doing ethics by opinion poll and legitimate empirical bioethics research?

A: Ethics by opinion poll merely aggregates and reports what people think should be done. Legitimate empirical bioethics uses empirical data to inform ethical analysis by:

- Illuminating the context of ethical decisions

- Testing empirical assumptions in ethical arguments

- Understanding how ethical principles are interpreted and applied in practice

- Identifying unanticipated ethical challenges [11] [16]

Q: How should we handle conflicting values or perspectives identified through empirical research?

A: Value conflicts should not be suppressed or ignored. Instead:

- Map the conflicts systematically using value taxonomy

- Analyze the sources and nature of disagreements

- Explore possibilities for resolution or accommodation

- Develop recommendations that acknowledge persistent disagreements where they exist

- Consider procedural solutions when substantive agreement is impossible [17]

Implementation and Analytical Challenges

Q: What sample sizes are appropriate for qualitative research in empirical bioethics?

A: Sample size in qualitative research is determined by the principle of saturation rather than statistical power. Typically, researchers continue data collection until no new themes or insights are emerging. For interview studies, this often occurs between 15-30 participants per stakeholder group, but can vary based on the diversity of perspectives and complexity of the topic [11].

Q: How can we ensure methodological rigor in qualitative empirical bioethics?

A: Ensure rigor through:

- Transparency about methods and limitations

- Triangulation of data sources and methods

- Member checking (validating interpretations with participants)

- Peer debriefing and independent analysis where possible

- Clear audit trails of analytical decisions [11] [15]

Q: What is the appropriate role of quantitative methods in empirical bioethics?

A: Quantitative methods are valuable for:

- Establishing prevalence of practices, attitudes, or experiences

- Identifying patterns and correlations in large datasets

- Testing hypotheses about factors influencing ethical decision-making

- Generalizing findings from qualitative research to larger populations However, quantitative data still requires normative interpretation and should not be viewed as mechanically determining ethical conclusions [16].

Advanced Integration Techniques and Validation

Digital Methods for Empirical Bioethics

Emerging digital methods offer new approaches for implementing the Bridge Postulate:

Table 2: Digital Methods for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Method | Description | Application Example | Technical Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational text analysis | Automated analysis of large text corpora | Identifying themes in social media discussions of bioethical issues | Natural language processing libraries, programming skills |

| Network analysis | Mapping relationships between concepts or stakeholders | Analyzing policy networks or conceptual relationships in ethics literature | Network analysis software, data visualization tools |

| Sentiment analysis | Automated classification of emotional valence in text | Tracking public sentiment about emerging technologies | Text analysis algorithms, validated dictionaries |

These digital methods can enhance traditional approaches by enabling analysis of larger datasets and identifying patterns that might not be apparent through manual methods alone [18].

Validation Framework for Empirical Bioethics Methods

Robust validation of methodological approaches is essential for ensuring the reliability of empirical bioethics research:

Validation Protocol: Methodological Quality Assessment

Objective: To establish that the chosen methodology reliably produces knowledge relevant to the research questions.

Methodology:

- Preliminary Development: Define method scope, endpoints, and analytical requirements

- Feasibility Testing: Verify that methods can be implemented as designed and produce useful data

- Internal Validation: Establish that methods produce consistent, reliable results within a single research context

- External Validation: Demonstrate that methods can be successfully implemented across different research contexts [19]

Quality Indicators:

- Transparency about methodological choices and limitations

- Appropriate handling of conflicting evidence and perspectives

- Explicit documentation of the integration process between empirical and normative elements

- Critical reflection on researcher positionality and potential biases

The Bridge Postulate provides a foundational principle for empirical bioethics research: while facts alone cannot determine values, and values alone cannot determine facts, a disciplined methodological bridge between them is both possible and essential for addressing complex bioethical challenges. The frameworks, methods, and troubleshooting guides presented here offer researchers practical approaches for implementing this postulate while maintaining philosophical rigor. By transparently documenting their bridging methodologies and critically reflecting on their integrative approaches, researchers can produce work that simultaneously respects the logical distinction between facts and values while building constructive pathways between them. This enables empirical bioethics to fulfill its potential of developing normative recommendations that are both philosophically sound and empirically informed.

Ethical Cognitivism as a Shared Meta-Ethical Postulate in Bioethics

FAQs: Navigating Meta-Ethical Foundations and Research Practice

FAQ 1: What is ethical cognitivism and why is it a foundational postulate in bioethics? Ethical cognitivism is the meta-ethical view that ethical sentences (e.g., "informed consent is obligatory") express propositions and can therefore be true or false (they are truth-apt) [20]. This stands in direct opposition to non-cognitivism, which denies that moral sentences express beliefs that can be true or false, instead viewing them as expressions of emotion, attitudes, or prescriptions [21].

Within bioethics, ethical cognitivism serves as a core shared postulate. This means that unless explicitly stated otherwise, bioethical discourse operates on the assumption that ethical statements are truth-apt and that knowledge is possible in ethics [2]. This foundational stance makes rational deliberation and argument about ethical issues possible, as it allows for the existence of correct and incorrect answers to ethical questions, which is crucial for guiding clinical practice and policy.

FAQ 2: How does cognitivism relate to the classic 'Is-Ought Problem' in empirical bioethics? The 'Is-Ought Problem' (Hume's Law) questions the logical derivation of normative claims ("ought") from descriptive facts ("is") and is often raised as a challenge to empirical bioethics [2]. The force of this challenge, however, is heavily dependent on one's meta-ethical stance.

A non-cognitivist interpretation of Hume's Law establishes a strict logical gulf between facts and values, making the integration of empirical data into normative reasoning particularly problematic [2]. In contrast, a cognitivist framework provides a different landscape. Cognitivism allows for the possibility that ethical propositions can be objectively true, even if not through a direct correspondence with physical entities [20]. This opens the door for more nuanced ways of bridging the "is-ought" gap, such as through coherence theories of truth or by viewing normative reasoning as analogous to other normative domains like mathematics [20]. Therefore, adopting ethical cognitivism as a postulate mitigates the logical threat of Hume's Law and supports the project of integrating empirical research with normative ethics.

FAQ 3: What are the practical implications of adopting a cognitivist stance for a research team? Adopting a cognitivist stance has direct consequences for research design and team discourse:

- Rational Resolution of Disagreements: Team members can operate on the premise that ethical disagreements are subject to rational argument and evidence, rather than being mere clashes of subjective preference. This encourages deliberation aimed at finding the most justified position.

- Clarity in Argumentation: It mandates that normative claims (e.g., "this trial design is unethical") be supported by reasons and evidence that purport to be truth-tracking, rather than being asserted as simple expressions of approval or disapproval.

- Framework for Empirical-Normative Integration: It provides a philosophical foundation for methodologies that seek to use empirical data (e.g., on patient preferences or quality of life) to inform normative conclusions, as it holds that such conclusions can be validly true or false [2].

FAQ 4: Our team is facing a disagreement on an ethical judgment. How can a shared cognitivist postulate guide our deliberation? A shared commitment to cognitivism provides a structured pathway for conflict resolution:

- Articulate Competing Propositions: Frame the disagreement as a conflict between two or more potentially truth-apt propositions (e.g., "Proposition A: Providing treatment X is obligatory" vs. "Proposition B: Providing treatment X is not obligatory").

- Identify Supporting Evidence and Principles: For each proposition, require advocates to present their supporting evidence, including relevant empirical data, ethical principles (e.g., beneficence, autonomy), and analogies to paradigm cases [22].

- Seek a Coherent Conclusion: Deliberate on which proposition forms the most coherent and justified conclusion based on the totality of the evidence and principles, with the goal of identifying the position most likely to be true.

FAQ 5: How can we methodologically bridge the "is-ought" gap when designing empirical bioethics research? The "Ought-Is" problem—translating established norms into practice—can be addressed by integrating principles from implementation science into the ethics research process [7]. The following workflow outlines a structured approach to bridge this gap.

Diagram 1: A framework for translating ethical norms into practice, integrating implementation science principles [7].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Scenarios and Solutions

Scenario 1: Handling Non-Cognitivist Challenges

- Problem: A colleague argues that a specific ethical recommendation is "just your opinion" and not objectively defensible, reflecting a non-cognitivist challenge.

- Diagnosis: This is a fundamental meta-ethical disagreement that can stall productive discussion.

- Solution:

- Re-affirm Shared Goal: Clarify that the team's default operating principle (postulate) is that ethical claims can be more or less justified based on reasons and evidence.

- Shift to Reasons: Ask the colleague to provide reasons why they disagree with the recommendation, thereby implicitly engaging in cognitivist practice.

- Appeal to Paradigm Cases: Reference clear, widely accepted ethical precedents (e.g., "It is wrong to experiment on humans without consent") to demonstrate that not all ethical judgments are merely subjective [22].

- Problem: A researcher is uncertain how to use descriptive data from a survey (an "is") to make a policy recommendation (an "ought").

- Diagnosis: This is a direct encounter with the Is-Ought problem in research practice.

- Solution:

- Make Normative Premises Explicit: The inference from data to recommendation requires at least one implicit normative premise. State it clearly.

- Empirical Finding (Is): 95% of patients in the study desire detailed information about all treatment risks.

- Explicit Normative Premise (Ought): Clinical practices ought to respect the autonomous preferences of patients where possible.

- Normative Conclusion (Ought): Therefore, clinicians ought to provide detailed information about all treatment risks.

- Use a Structured Framework: Employ a structured framework, like the "four boxes" method, to organize the empirical facts and their relationship to key ethical principles [22]. This makes the normative reasoning process transparent and systematic.

- Make Normative Premises Explicit: The inference from data to recommendation requires at least one implicit normative premise. State it clearly.

Scenario 3: Managing Disagreement on Risk-Benefit Analysis

- Problem: The research team is deadlocked over whether the potential benefits of a novel drug outweigh its risks in a clinical trial.

- Diagnosis: Disagreement may stem from different weightings of the same facts or from differing interpretations of incomplete data.

- Solution:

- Deconstruct the Analysis: Break down the risk-benefit judgment into its component propositions using a structured table.

- Systematic Deliberation: Use the table to isolate the precise points of disagreement, focusing deliberation on the evidence for each component.

Table 1: Framework for Deconstructing a Risk-Benefit Disagreement

| Component Proposition | Evidence (Facts/ 'Is') | Conflicting Interpretations / Weightings ('Ought' Judgments) |

|---|---|---|

| Benefit is clinically significant. | Phase II data shows 40% tumor reduction in 30% of participants. | View A: This represents a meaningful therapeutic benefit for a severe condition. View B: The effect is not robust enough to be considered significant. |

| Risks are manageable. | 15% of participants experienced severe but reversible side effects. | View A: The reversibility makes these risks acceptable. View B: A 15% rate of severe events is unacceptably high. |

| The risk-benefit profile is favorable. | Synthesis of the above data. | View A: The potential for significant benefit justifies the known risks. View B: The severity and frequency of risks outweigh the uncertain benefit. |

Table 2: Essential Meta-Ethical and Methodological "Reagents" for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Conceptual Tool | Function in Research | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical Cognitivism [20] [2] | Provides the foundational postulate that ethical statements can be true or false, enabling rational argument and knowledge accumulation in ethics. | Truth-apt, belief-expressing, encompasses both realism and error theory. |

| The Four-Topics Method [22] | A structured clinical ethics tool for case analysis; organizes facts of a case into Medical Indications, Patient Preferences, Quality of Life, and Contextual Features to facilitate ethical decision-making. | Practical, case-based, promotes systematic and comprehensive analysis. |

| Implementation Science Framework [7] | Provides a disciplined approach to translating established ethical norms ("ought") into widespread practice ("is"), addressing the "Ought-Is" problem. | Focused on sustainability, assesses barriers and facilitators (e.g., via CFIR). |

| Aspirational vs. Specific Norms [7] | Distinguishes between broad, inspirational ethical goals and concrete, actionable rules, guiding the development of feasible research interventions. | Aspirational: General, "true North." Specific: Directed, incremental, feasible. |

| Paradigm Case [22] | A clear, precedent-setting case where there is broad agreement on the ethical resolution; used as an analogical reference point for analyzing novel cases. | Provides reference, aids in pattern recognition, and grounds ethical reasoning. |

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Frameworks for Integration

Reflective equilibrium is a state of balance or coherence among a set of beliefs arrived at by a process of deliberative mutual adjustment among general principles and particular judgements [23]. Philosopher John Rawls, who coined the term, proposed this method to address concerns that our moral judgments alone may not justify the moral views they express, as they can be "fraught with idiosyncrasy and vulnerable to vagaries of history and personality" [24]. The method provides a systematic approach to moral reasoning that allows us to generate considered moral judgments from a wide variety of initial beliefs and intuitions [25].

In empirical bioethics research, reflective equilibrium offers a crucial methodological framework for addressing the is-ought gap—the philosophical challenge of deriving normative claims ("ought") from empirical facts ("is") [7]. By providing a structured process for moving between empirical observations and normative principles, reflective equilibrium helps researchers navigate this traditional divide in a principled manner.

The Three Levels of Moral Inquiry

The process of reflective equilibrium involves reflecting on three interconnected levels of moral thinking [25]:

- Level 1: Particular Case Judgments: Intuitive moral responses to specific situations or cases

- Level 2: General Moral Principles: Mid-level rules that guide decision-making across multiple cases

- Level 3: Theoretical Considerations: Broader philosophical theories and background considerations

The Iterative Process

Reaching reflective equilibrium requires continuous adjustment among these three levels [24] [25]. When conflicts arise between different levels—for instance, when a general principle conflicts with multiple considered judgments about particular cases—we must adjust our views at each level until we achieve coherence. This process continues until our principles, judgments, and background theories form a stable, coherent set [23].

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Challenges

FAQ: Frequently Encountered Problems

Q: What should I do when my general principles consistently conflict with my intuitions about specific cases? A: This indicates a need to refine your principles. Don't automatically discard either element—instead, examine whether your principles are overly broad or whether your intuitions might be influenced by bias. Consider formulating exception clauses or intermediate principles that can accommodate the conflicting judgments while maintaining theoretical coherence [24] [25].

Q: How do I handle situations where I have low confidence in my moral judgments? A: Rawls suggests we can "discard those judgments made with hesitation, or in which we have little confidence" [24]. However, an alternative view suggests that lack of confidence alone shouldn't exclude judgments from consideration, as they may represent important but underdeveloped moral commitments that could find support during the reflective process [24].

Q: What happens when background theories from different disciplines provide conflicting guidance? A: This is common in interdisciplinary bioethics research. The solution is to engage in "wide reflective equilibrium," which involves considering all relevant philosophical arguments and scientific evidence, then seeking the most coherent combination of these elements, even if this requires revising initial commitments [24] [23].

Q: How can I address the is-ought gap when applying reflective equilibrium in empirical bioethics? A: Rather than viewing the is-ought gap as an insurmountable barrier, treat it as a warning sign to critically reflect on the normative implications of empirical results [11]. The iterative process of reflective equilibrium allows for normative principles to be tested against empirical reality and empirical observations to be interpreted through normative frameworks.

Common Implementation Errors and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Reflective Equilibrium Implementation Problems

| Problem Scenario | Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistent inability to reach coherence between principles and judgments | Overly rigid adherence to initial principles | Consider "radical" reflective equilibrium allowing comprehensive revision of initial beliefs [24] | Adopt a provisional attitude toward all moral beliefs at the outset |

| Circular justification where principles simply restate judgments | Lack of critical distance from initial intuitions | Introduce new cases or theoretical perspectives to break the circularity | Systematically seek out counterexamples and challenging cases |

| Disregard of relevant empirical evidence | Artificial separation of empirical and normative inquiry | Actively incorporate scientific background theories into wide reflective equilibrium [23] | Form interdisciplinary teams with both empirical and normative expertise |

| Paralysis from constant revision | Lack of provisional fixed points | Identify "considered judgments" that serve as relatively stable reference points [24] | Recognize that reflective equilibrium is always provisional and can be revisited |

Research Protocols for Empirical Bioethics Applications

Protocol 1: Establishing Wide Reflective Equilibrium in Bioethics Research

Purpose: To develop morally coherent positions on bioethical issues through systematic integration of considered judgments, moral principles, and relevant background theories [23].

Methodology:

- Identify Considered Judgments: Collect moral intuitions about specific cases under conditions conducive to moral deliberation (adequate information, emotional calm, impartiality) [24]

- Articulate Candidate Principles: Formulate general principles that potentially explain the considered judgments

- Gather Background Theories: Collect relevant scientific facts, philosophical arguments, and practical constraints

- Test for Coherence: Identify conflicts between judgments, principles, and theories

- Engage in Mutual Adjustment: Revise elements at all levels to achieve greater coherence

- Achieve Equilibrium: Continue process until arriving at a stable, coherent set of beliefs

Validation Measure: The robustness of the resulting position is measured by its ability to withstand challenging counterexamples and explain a wide range of moral judgments [24].

Protocol 2: Bridging the Is-Ought Gap Through Implementation Science

Purpose: To translate ethical norms into practice by integrating implementation science principles with reflective equilibrium [7].

Methodology:

- Develop Aspirational Norms: Formulate broad ethical ideals (e.g., "No one should die of hunger")

- Specify Actionable Norms: Develop specific, implementable norms through reflective equilibrium (e.g., "Physicians should screen for food insecurity")

- Design Interventions: Create practical interventions to enact the specific norms

- Measure Outcomes: Implement interventions and assess their effectiveness

- Refine Through Reflection: Use empirical results to refine norms and principles through reflective equilibrium

Validation Measure: Successful implementation of ethical norms in practice, measured through both ethical coherence and practical effectiveness [7].

Analytical Framework for Assessing Moral Coherence

Quantitative Measures of Reflective Equilibrium

Table 2: Metrics for Evaluating Progress Toward Reflective Equilibrium

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Interpretation Guidelines | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coherence Indicators | Number of unresolved conflicts between principles and judgments | Fewer conflicts indicate progress toward equilibrium | Documentation of reasoning process |

| Scope of cases explained by principle set | Broader explanatory scope indicates more robust equilibrium | Case analysis records | |

| Stability Measures | Frequency of revision required for core principles | Decreasing revision frequency suggests approaching equilibrium | Version control of principle formulations |

| Resilience to new counterexamples | Resistance to disruption by new cases indicates mature equilibrium | Testing with novel cases | |

| Empirical-Normative Integration | Number of empirical facts successfully incorporated into normative framework | Higher integration indicates successful wide reflective equilibrium [23] | Interdisciplinary research documentation |

Key Conceptual Tools for Implementing Reflective Equilibrium

Table 3: Essential Methodological Resources for Reflective Equilibrium Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tool | Function in Research Process | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Judgment Refinement Tools | "Considered judgment" criteria [24] | Identifies which moral intuitions to include in the process | Filtering out judgments made under emotional distress |

| Confidence assessment | Prioritizes judgments based on certainty level | Focusing adjustment efforts on low-confidence areas | |

| Theoretical Integration Tools | Wide reflective equilibrium framework [23] | Incorporates background theories and philosophical arguments | Integrating scientific facts about pain perception into end-of-life ethics |

| Principles-judgments-case triads | Structures the relationship between different belief levels | Mapping connections between autonomy principle and specific consent decisions | |

| Implementation Tools | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [7] | Identifies barriers and facilitators for translating norms to practice | Assessing organizational readiness for new ethical guidelines |

Advanced Application: Addressing the Is-Ought Gap in Bioethics

The method of reflective equilibrium provides a systematic approach to addressing the fundamental is-ought challenge in empirical bioethics research. Rather than attempting to derive normative conclusions directly from empirical facts, reflective equilibrium creates a structured process for mutual adjustment between empirical observations and normative principles [11].

Research with bioethics scholars reveals that the most accepted objectives for empirical research in bioethics include "understanding the context of a bioethical issue" and "identifying ethical issues in practice" [11]. These objectives align well with the reflective equilibrium method, which uses empirical findings to test, refine, and develop moral principles through an iterative process of reflection and adjustment.

The implementation science framework complements this approach by providing a pathway from normative reflection to practical action, creating a complete cycle from empirical observation to normative refinement to practical implementation and back to empirical assessment [7]. This integrated approach acknowledges that "ethical statements that pose as short-term action items but cannot be implemented might foster guilt, cynicism, or despondency and inaction" [7], thus emphasizing the importance of feasible normative guidance.

Frequently Asked Questions

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is the primary goal of Dialogical Empirical Ethics? | To address ethical issues by setting up structured dialogues with stakeholders, using their concrete experiences as a source for moral learning and developing normative conclusions together, rather than the ethicist working in isolation [26]. |

| How can this method help bridge the "is-ought" gap? | It tackles the is-ought problem by treating empirical data not as a direct source of norms, but as a crucial element for reflection within a dialogical process. This process helps test and develop normative stances that are grounded in the reality of practice [12] [6]. |

| What is a common challenge when integrating empirical data with normative analysis? | The process is often experienced as vague or unclear. Methodologies like reflective equilibrium and dialogical approaches can be frustratingly indeterminate in practice, risking a lack of theoretical rigor [12]. |

| What is the role of the ethicist in this process? | The ethicist acts as a facilitator of the dialogical process, guiding the exchange of experiences and reflection among stakeholders to shape normative conclusions, rather than being the sole analyst [26]. |

| Which objectives of empirical research in bioethics are most acceptable to researchers? | Understanding the context of a bioethical issue and identifying ethical issues in practice receive strong support. Objectives like drawing direct normative recommendations or justifying moral principles are more contested [6]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Unclear Methodological Path for Integration

- Symptoms: Uncertainty about how to combine empirical findings (the "is") with ethical analysis (the "ought"); confusion between different methodologies like reflective equilibrium and dialogical ethics.

- Solution:

- Clearly State Theoretical Position: Justify why a particular methodological approach (e.g., dialogical, consultative) was chosen for your project [12].

- Choose a Structured Dialogical Method: Adopt a framework like Responsive Evaluation, which involves eliciting stakeholder stories, exchanging experiences in homogeneous and heterogeneous groups, and collectively drawing normative conclusions [26].

- Document the Process: Be transparent about how the integration was carried out step-by-step to mitigate vagueness [12].

- Symptoms: Criticism that the research is attempting to derive normative claims directly from descriptive data; difficulty in defending the normative weight of the study's outcomes.

- Solution:

- Frame the Gap as a Warning, Not a Barrier: Treat the is-ought gap as a critical signpost to reflect on the limits of your empirical data, not as an insurmountable obstacle [6].

- Use Empirical Data as a Testing Ground: Position your empirical findings as a way to test, challenge, and refine existing elements of normative theory, rather than as the sole foundation for new norms [6].

- Facilitate Normative Dialogue: Do not let stakeholders' experiences be the final word. Use facilitated dialogue to critically reflect on these experiences and co-develop justified normative positions [26].

Problem: Stakeholder Consensus is Elusive

- Symptoms: Dialogues reach an impasse because of conflicting values or perspectives among participants; inability to draw a coherent normative conclusion.

- Solution:

- Shift the Goal from Consensus to Learning: Frame the primary output of the dialogue as mutual moral learning and a deeper understanding of the problem, which can be valuable even without full consensus [26].

- Use Homogeneous Groups: Before bringing all stakeholders together, first facilitate dialogues within homogeneous groups (e.g., patients only, clinicians only) to build confidence and clarify internal perspectives [26].

- The Ethicist's Normative Contribution: As a facilitator, you can enrich the process by carefully introducing ethical concepts and theories to help participants navigate their disagreements and structure their reflections [26] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function in Dialogical Empirical Ethics |

|---|---|

| Structured Dialogue Protocol | A pre-defined format (e.g., from Responsive Evaluation) to guide discussions, ensuring they are productive and systematically capture all relevant experiences and normative reflections [26]. |

| Stakeholder Maps | A visual or descriptive tool identifying all relevant parties (patients, clinicians, policymakers) and their relationships, which is crucial for inclusive and representative sampling [26]. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | A set of open-ended questions used to elicit detailed stories and perspectives from participants, providing the rich, qualitative empirical data for the dialogical process [26]. |

| Ethical Framework Primer | A simplified overview of key ethical principles (e.g., autonomy, beneficence) and theories, used by the facilitating ethicist to inform and enrich stakeholder discussions without imposing conclusions [12]. |

| Integration Methodology Handbook | A reference document detailing methods like Wide Reflective Equilibrium or Hermeneutic analysis, helping researchers navigate the back-and-forth between empirical data and normative reasoning [12]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Dialogical Ethics Study

Objective: To develop and implement normative guidelines for improving the practice concerning coercion and compulsion in psychiatry through stakeholder collaboration [26].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Project Scoping and Stakeholder Mapping

- Identify all key stakeholder groups (e.g., patients with lived experience, psychiatrists, nurses, hospital administrators, family advocates).

- Define the specific ethical issue and the scope of the desired normative guidelines.

Empirical Data Elicitation

- Conduct in-depth, semi-structured interviews with individuals from each stakeholder group.

- Focus on collecting concrete, detailed narratives about their experiences with and perspectives on coercion and compulsion in psychiatric care.

Structured Dialogical Exchange

- Homogeneous Dialogues: Convene separate focus groups for each stakeholder type (e.g., a patient-only group). Present anonymized data and facilitate discussion to develop group-specific insights.

- Heterogeneous Dialogue: Bring representatives from all stakeholder groups together. Facilitate a structured conversation where experiences from the homogeneous dialogues are shared and debated.

Normative Analysis and Conclusion Drawing

- The facilitating ethicist guides the heterogeneous group in a reflective process to identify common values, resolve conflicts, and draft normative guidelines that are informed by the shared dialogue.

- This involves a continuous "back-and-forth" between the collected experiences (empirical data) and ethical principles (normative analysis) [12].

Implementation and Reflexivity

- Present the co-created guidelines back to the broader practice community for feedback.

- Plan for the implementation of the guidelines and establish methods for ongoing monitoring and reflexive evaluation of their impact and ethical soundness in practice.

Methodological Pathways for Empirical Bioethics

The following diagram illustrates the primary methodological approaches for integrating empirical data with normative analysis, as identified in recent research [12].

The Dialogical Empirical Ethics Workflow

This workflow outlines the key phases of a project using dialogical ethics, from initial problem identification to the implementation of co-created normative guidance [26].

Empirical bioethics faces a fundamental challenge: how to integrate descriptive empirical data ("what is") into normative ethical reasoning ("what ought to be") without committing logical fallacies. This dilemma, often referred to as Hume's Law or the is-ought problem, establishes that no set of purely descriptive statements can logically entail an evaluative statement without at least one evaluative premise [2]. Symbiotic empirical ethics offers a practical methodology that addresses this challenge by creating a reciprocal relationship between ethical theory and practice, where each informs and refines the other in an iterative process [27].

This technical support guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical frameworks for implementing symbiotic empirical ethics within their work, enabling them to navigate the is-ought gap while developing ethically robust research practices and interventions.

Theoretical Foundations: Understanding the Is-Ought Problem

Key Concepts and Distinctions

The is-ought problem is frequently conflated with two other distinct concepts in bioethics literature. The table below clarifies these essential distinctions:

Table 1: Key Meta-ethical Concepts in Empirical Bioethics

| Concept | Definition | Primary Proponent | Relevance to Empirical Bioethics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hume's Law (Is-Ought Problem) | No set of descriptive statements alone can entail an evaluative statement without at least one evaluative premise [2] | David Hume | Creates logical limitations for deriving norms directly from empirical data |

| Naturalistic Fallacy | The logical fallacy of defining "good" in terms of natural properties [2] | G.E. Moore | Represents a meta-ethical refutation of ethical naturalism |

| Fact-Value Distinction | The view that factual statements and value statements have different truth-aptness [2] | Various | Suggests science is value-free, though this is contested |

The "Ought-Is" Problem: Implementing Ethical Norms

A complementary challenge to the traditional is-ought problem is the "ought-is" problem: how to implement ethical rules or norms to ensure they fulfill their primary purpose once developed [7]. This implementation challenge requires an "implementation mindset" where ethicists consider whether norms can feasibly be enacted, as ethical statements that cannot be implemented may foster "guilt, cynicism, or despondency and inaction" [7].

The Symbiotic Empirical Ethics Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide

Symbiotic empirical ethics is based on a naturalistic conception of ethical theory that sees practice as informing theory just as theory informs practice [27]. The methodology uses ethical theory both to explore empirical data and to draw normative conclusions through a structured process.

Table 2: The Five-Step Symbiotic Empirical Ethics Process

| Step | Process | Key Activities | Theoretical-Practice Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define Ethical Question & Select Normative Framework | Identify concrete ethical problem; Select appropriate ethical theory based on adequacy for issue and research design [28] | Theoretical foundation guides empirical inquiry |

| 2 | Collect Empirical Data | Qualitative/quantitative data gathering on real-world ethical challenges and stakeholder experiences [29] | Practice generates evidence about actual ethical phenomena |

| 3 | Analyze Data Through Theoretical Lens | Apply selected ethical framework to interpret empirical findings; Identify tensions between theory and practice [27] | Theory provides interpretive structure for understanding practice |

| 4 | Refine Ethical Theory | Modify theoretical framework based on empirical insights; Develop new normative concepts addressing practice gaps [27] | Practice reveals limitations in theory, driving theoretical development |

| 5 | Develop Practical Recommendations | Formulate specific, implementable ethical guidelines and interventions informed by refined theory [29] | Refined theory generates more practically adequate norms |

Workflow Diagram: Symbiotic Ethics Process

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Challenges

Frequently Encountered Problems and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Symbiotic Ethics Implementation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Data to Collect | Solution Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty integrating empirical findings with normative analysis | Conflation of Hume's Law with naturalistic fallacy; Underdeveloped ethical framework [2] | Document precise nature of disjunct between data and theory; Map argumentative structure of inferences | Explicitly articulate evaluative premises; Adopt "bridge postulate" that facts-values connection is possible [2] |

| Ethical recommendations are not implemented in practice | "Ought-is" gap: failure to consider implementation feasibility during norm development [7] | Stakeholder engagement data; Resource constraints; Organizational barriers | Apply implementation science principles during norm development; Develop "specific norms" rather than only "aspirational norms" [7] |

| Stakeholder resistance to ethical recommendations | Theory selection mismatch with practical context; Inadequate attention to relational dimensions [28] [29] | Qualitative data on stakeholder values and concerns; Analysis of relational networks in practice context | Select ethical theory based on adequacy for issue and research design; Foreground relational aspects of ethics [28] [29] |

| Uncertainty about which ethical theory to select | Pluralism of ethical theories; Lack of clear selection criteria [28] | Map specific requirements of research question; Identify theoretical commitments of stakeholders | Apply systematic criteria: adequacy for issue, suitability for research design, alignment with empirical approaches [28] |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

Table 4: Essential Methodological Components for Symbiotic Ethics Research

| Methodological Component | Function | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Data Collection Methods | Gather rich, contextual data on ethical experiences and challenges | Interviews, focus groups with healthcare professionals on resetting services during pandemic [29] |

| Implementation Science Frameworks | Support enactment and sustainability of ethical interventions | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) assessing intervention characteristics, settings [7] |

| Ethical Theory Selection Criteria | Provide systematic approach to choosing appropriate normative framework | Criteria of adequacy, suitability, and empirical alignment [28] |

| Translational Ethics Framework | Guide movement from abstract norms to concrete practices | Sisk et al.'s framework: Aspirational Norms → Specific Norms → Best Practices [7] |

| Mixed Judgment Analysis | Structure integration of normative and empirical propositions | Explicitly tracing normative and descriptive premises in ethical conclusions [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Implementing Symbiotic Ethics

Phase 1: Study Design and Theory Selection

- Define Concrete Ethical Problem: Formulate specific, practice-based ethical question rather than abstract theoretical problem

- Select Ethical Theory: Apply three criteria for theory selection [28]:

- Adequacy: Theory must appropriately address the specific ethical issue

- Suitability: Theory must align with research purposes and design

- Empirical Alignment: Consider interrelation between ethical theory and theoretical backgrounds of socio-empirical research

- Develop Data Collection Protocols: Design empirical methods that will generate data relevant to both theoretical refinement and practical application

Phase 2: Data Collection and Integration

- Gather Empirical Data: Collect qualitative and/or quantitative data on actual ethical practices, challenges, and stakeholder perspectives

- Initial Theoretical Analysis: Apply selected ethical framework as interpretive lens for preliminary data analysis

- Identify Theory-Practice Tensions: Document specific points where empirical findings challenge, extend, or refine existing theoretical framework