Bridging the Gap: A Practical Framework for Integrating Normative and Empirical Approaches in Bioethics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating normative and empirical methodologies in bioethics.

Bridging the Gap: A Practical Framework for Integrating Normative and Empirical Approaches in Bioethics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating normative and empirical methodologies in bioethics. It explores the foundational principles of this interdisciplinary field, critiques prevalent methodological challenges like the 'vagueness' of integration, and presents actionable strategies for selecting ethical frameworks and designing robust studies. By addressing key hurdles and offering comparative analysis of different approaches, the content aims to equip scientists with the tools to conduct ethically sound, methodologically rigorous, and socially relevant research in the biopharmaceutical sector and beyond.

The Foundations of Empirical Bioethics: Defining the Normative-Empirical Nexus

Empirical bioethics is an interdisciplinary research field that seeks to integrate empirical findings from the social sciences with normative philosophical analysis to address bioethical issues [1]. The growth of this field is largely attributed to a dissatisfaction with purely philosophical approaches, which were perceived as insufficient to address the complex reality of human practices in healthcare and biomedical research [1]. This integrative discipline fundamentally grapples with a central philosophical challenge: how can descriptive facts about the world (the "is") inform prescriptive ethical recommendations (the "ought")? [2] [3]. Empirical bioethics does not claim that empirical data alone can determine what is right or wrong, but rather that such data provides essential context, identifies practical challenges, and tests the feasibility of ethical ideals, thereby enriching normative analysis [4] [3].

Defining the Terrain: What Constitutes Empirical Bioethics?

Core Characteristics and Aims

Empirical bioethics is characterized by its commitment to interdisciplinary work. It centers on the integration of empirical research—which can be qualitative or quantitative—with ethical argument to arrive at normative conclusions [1]. The ultimate aim of this endeavor is not empirical research for its own sake, but to produce knowledge that can inform and improve real-world practices and policies [2] [5].

A key insight from the field is that ethically relevant empirical data are ubiquitous, often appearing in publications outside traditional ethics journals. Seminal studies that have influenced bioethical norms, such as analyses of tube feeding in advanced dementia or placebo use in antidepressant trials, were frequently conducted by researchers who do not identify as bioethicists and published in clinical journals without ethics-specific keywords [4]. This underscores the importance for bioethicists to engage with literature beyond their immediate discipline.

A Framework for Empirical Bioethics Research

One influential framework conceptualizes empirical bioethics research as comprising three hierarchical phases, conveyed through the metaphor of landscaping [5]:

Table 1: The Mapping-Framing-Shaping Framework for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Phase | Primary Aim | Typical Activities | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mapping | Survey the existing terrain | Literature reviews; analysis of previous scholarship and data | Understanding of the "state of the art" and identification of knowledge gaps |

| Framing | Explore specific areas in depth | Qualitative or quantitative research with stakeholders to understand lived experiences | Fine-grained understanding of how issues are experienced and perceived |

| Shaping | Propose normative recommendations | Integrative analysis using a bridging methodology | Ethically robust recommendations for practice or policy |

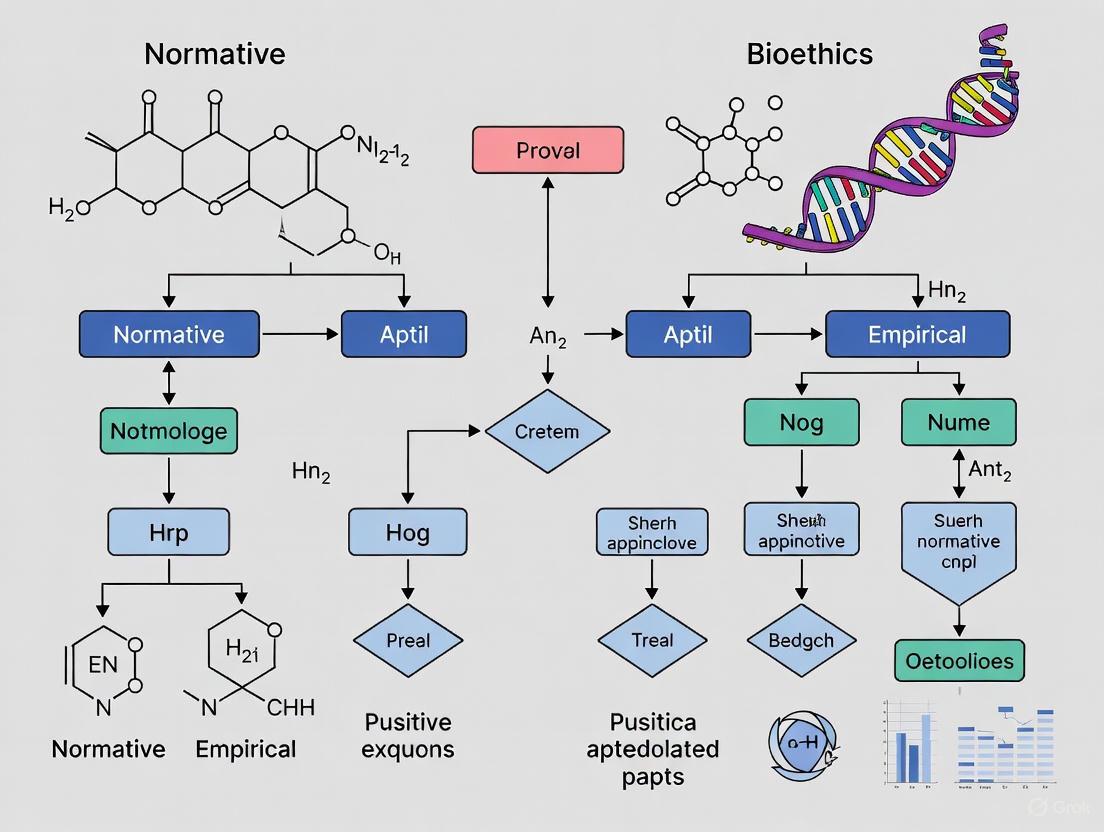

Figure 1: The three-phase empirical bioethics research workflow, highlighting integration as the definitive step.

The critical element that distinguishes empirical bioethics from merely conducting empirical research on an ethics-adjacent topic is the integration step, where methodology is explicitly used to bridge the empirical findings with normative analysis [5]. This integration is what allows the researcher to move from description to prescription.

Methodological Approaches and Integration Strategies

Classifying Empirical Research in Bioethics

Empirical research can inform bioethics at different levels. One prominent classification system identifies four hierarchical categories, from descriptive to normative [2]:

Table 2: A Hierarchical Classification of Empirical Research in Bioethics

| Category | Primary Question | Example | Normative Ambition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lay of the Land | What are current practices, opinions, or beliefs? | Surveys of end-of-life care preferences among patients and providers [2] | Descriptive; sets the stage for further inquiry |

| Ideal vs. Reality | To what extent does practice match ethical ideals? | Studies documenting racial disparities in healthcare delivery [2] | Identifies ethical failures in practice |

| Improving Care | How can we bring practice closer to ethical ideals? | Interventions to improve informed consent comprehension [3] | Develops and tests practical interventions |

| Changing Ethical Norms | Should our ethical norms evolve based on evidence? | Using data on outcomes of tube feeding in dementia to reconsider norms [4] | Aims to refine or revise ethical norms |

Methodologies for Integration

A systematic review has identified at least 32 distinct methodologies for integrating empirical research with normative analysis [1]. These can be broadly categorized into three approaches:

Consultative Approaches: The researcher acts as an external thinker who independently analyzes empirical data and ethical theory to develop a normative conclusion. The most prominent example is reflective equilibrium (or "wide reflective equilibrium"), a process where the researcher moves back-and-forth between ethical principles, considered moral judgments, and empirical facts until a state of coherence ("equilibrium") is reached [1].

Dialogical Approaches: These methods rely on structured dialogue between stakeholders (including researchers, participants, and other relevant actors) to reach a shared understanding and normative conclusion. In these approaches, the ethicist often acts as a facilitator rather than the sole arbiter of the ethical analysis [1].

Combined Approaches: Some methodologies blend elements of both consultative and dialogical approaches, such as hermeneutical methods that interpret the meaning of practices through both engagement and reflection [1].

Despite this diversity, researchers in the field often report that the integration process remains somewhat vague in practice, representing both a strength (flexibility) and a weakness (potential obscurity) [1].

Experimental Protocols in Empirical Bioethics

A Generic Protocol for Qualitative Framing Studies

Objective: To explore and understand how a specific bioethical issue is experienced and framed by relevant stakeholders.

Methodology: This protocol employs a qualitative exploratory design, typically using semi-structured interviews or focus groups [6].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Qualitative Framing Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Research Process |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Recruitment | Systematic sampling from clinical populations; purposive sampling of experts | Ensures the inclusion of relevant perspectives and experiences |

| Data Collection Tools | Semi-structured interview guide; audio recording equipment; secure storage | Facilitates consistent, in-depth data collection while protecting participant confidentiality |

| Data Management | Qualitative data analysis software (e.g., MAXQDA, NVivo); transcription services | Enables systematic organization, coding, and analysis of complex qualitative data |

| Analytical Framework | Thematic analysis guide (e.g., Braun & Clarke, 2006) [1]; codebook | Provides a structured yet flexible method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within the data |

Procedure:

- Ethics Approval: Obtain approval from an accredited Research Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board.

- Sampling: Identify and recruit a purposive sample of participants who have direct experience with the bioethical issue under investigation. Sample size is typically determined by the principle of saturation, where new data no longer yields new thematic insights [6].

- Data Collection: Conduct individual interviews or focus groups using a semi-structured guide. All sessions should be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to ensure accuracy.

- Data Analysis: Employ thematic analysis, which involves (a) familiarization with the data, (b) generating initial codes, (c) searching for themes, (d) reviewing themes, (e) defining and naming themes, and (f) producing the report [1] [7].

- Integration: The empirical findings (themes) are then integrated with normative analysis using a chosen methodology (e.g., reflective equilibrium) to develop ethical recommendations.

A Protocol for a "Changing Ethical Norms" Study

Objective: To use a body of empirical evidence to form the basis of an argument for refining or changing an established ethical norm.

Methodology: This approach involves a comprehensive evidence synthesis and normative analysis, often building on multiple existing studies rather than a single primary investigation [2] [8].

Procedure:

- Evidence Mapping: Conduct a systematic review of the literature to gather all relevant empirical data related to the ethical norm in question (e.g., clinical outcomes, patient experiences, stakeholder perspectives).

- Critical Appraisal: Assess the quality, consistency, and applicability of the gathered evidence. A single study is rarely sufficient to warrant a change in ethical norms; a body of credible evidence is required [8].

- Identify Normative Implications: Analyze how the empirical evidence challenges, supports, or complicates the assumptions underlying the current ethical norm. This involves testing whether what is "ought" is, in fact, possible ("ought implies can") [9] or examining the consequences of adhering to a norm in practice [3].

- Construct a Normative Argument: Develop a reasoned argument for how the ethical norm should be refined, contextualized, or changed in light of the evidence. This is not a direct derivation from facts to values, but a structured justification that gives appropriate weight to both empirical findings and ethical principles [2] [8].

- Propose Refined Norms or Applications: Articulate the proposed change to the norm or its application in specific contexts, clearly outlining the ethical reasoning that bridges the empirical evidence and the normative conclusion.

Current Trends and Digital Innovations

The field of empirical bioethics is increasingly embracing digital methods, giving rise to "digital bioethics." This involves using online and digital technologies to collect and analyze research data, such as analyzing discussions on social media platforms to understand public perspectives on emerging ethical issues [10].

These novel approaches leverage computational capabilities, including natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning, to handle large datasets. However, they also introduce a dependence on technical skills not typically part of a bioethicist's training. In response, platform prototypes are being developed to empower researchers without advanced programming expertise to leverage these digital methods, for instance, by providing modular components for data collection, filtering, and analysis that can be configured through a graphical interface [10]. This innovation aims to make digital bioethics more accessible and to foster methodological development.

Empirical bioethics represents a vital maturation of bioethical inquiry, moving beyond abstract theorizing to engage seriously with the realities of clinical practice and human experience. Its core contribution lies in its integrative imperative—the insistence that robust ethical analysis requires both empirical vigilance and normative sophistication. By systematically mapping the terrain, framing issues through the perspectives of those most affected, and leveraging methodological rigor to shape recommendations, empirical bioethics provides a powerful framework for addressing the most pressing challenges in healthcare and biomedical research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, engaging with this approach is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for developing ethically sound and practically feasible policies and practices.

Integrating normative and empirical approaches represents a significant methodological frontier in contemporary bioethics research. This integration, however, is often characterized by substantial vagueness and a lack of clarity in practical execution. This article provides structured application notes and protocols to guide researchers in systematically disentangling and then purposefully reintegrating empirical data with normative analysis. By synthesizing established methodologies such as symbiotic empirical ethics, reflective equilibrium, and dialogical empirical ethics, we present a structured framework to enhance methodological rigor. The protocols include detailed workflows, reagent solutions for interdisciplinary research, and visualization tools designed to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate the complexities of empirical bioethics research, ultimately leading to more transparent and defensible normative conclusions.

Empirical bioethics is an interdisciplinary field that centers on the integration of empirical findings with normative, philosophical analysis [1]. The growth of this field is largely attributed to a dissatisfaction with purely philosophical approaches, which are often perceived as insufficient for addressing the complex, real-world nuances of bioethical issues [1]. An empirically informed bioethics is better suited to deal with the complexity of human practices. Despite a consensus on the relevance of empirical research to bioethical argument, the process of integration remains challenging [1]. A systematic review has identified at least thirty-two distinct methodologies for integration, revealing a field rich with innovation but also struggling with uncertainty about the particular aims, content, and domain of application for these methods [1]. Many existing methodologies risk being "frustratingly vague and insufficiently determinate in practical contexts" [1]. This article aims to address this vagueness by providing clear, actionable protocols and tools for researchers seeking to untangle and then meaningfully weave together the normative and empirical threads of their work.

Core Methodologies in Empirical Bioethics

The first step in untangling normative and empirical components is to understand the primary methodological frameworks available. The choice of framework dictates how empirical data and ethical analysis will interact throughout the research process.

Table 1: Core Methodologies for Integrating Normative and Empirical Analysis

| Methodology | Key Feature | Process of Integration | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective Equilibrium [1] | A back-and-forth, coherence-seeking method performed by the researcher. | The researcher ("the thinker") iteratively revises ethical principles, empirical data, and considered judgements until moral coherence ("equilibrium") is achieved. | Consultative research where the researcher acts as an external analyst. |

| Symbiotic Empirical Ethics [11] | A naturalist approach viewing ethical theory and practice as symbiotically related. | A structured five-step process moving from empirical data to the refinement of ethical theory, ensuring practice informs theory and vice-versa. | Research aiming to develop or refine ethical theory based on concrete practical findings. |

| Dialogical Empirical Ethics [1] | Relies on stakeholder dialogue to reach a shared, normative understanding. | Collaboration and discourse between researchers, participants, and other stakeholders are the primary mechanism for developing normative conclusions. | Participatory action research and contexts where stakeholder buy-in is critical. |

| Ground Moral Analysis [1] | Integrates empirical data collection with normative analysis from the outset. | The normative and empirical are intertwined from the start of the research project, often using a grounded theory approach. | Exploratory research where ethical concepts are expected to emerge from the data. |

Application Protocol: Symbiotic Empirical Ethics

The symbiotic empirical ethics methodology, as developed by Frith, provides a structured, five-step protocol for moving from empirical findings to normative suggestions [11]. This approach is particularly valuable for making explicit the process of developing ethical theory based on practical data.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Objective: To generate normative ethical solutions or theory refinements grounded in empirical qualitative data concerning a specific ethical challenge in healthcare or research settings.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Identify a Practice-Based Problem: Begin with a concrete ethical problem or challenge observed in clinical or research practice. For example, the Reset Ethics project began with the problem of how to ethically integrate Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures into routine maternity and paediatric services during the COVID-19 pandemic [11].

- Gather Qualitative Empirical Data: Collect rich, contextual data on the identified problem. This typically involves qualitative methods such as:

- Semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders (e.g., healthcare professionals, patients, administrators).

- Focus group discussions to explore shared and divergent experiences.

- The data should capture the lived experiences and ethical challenges of those directly involved.

- Conduct Thematic Analysis: Analyze the qualitative data using standard thematic analysis techniques. This involves:

- Transcribing interviews and focus groups verbatim.

- Systematically coding the data to identify recurring patterns and themes.

- Developing overarching themes that capture the core ethical tensions or insights present in the data. In the Reset project, a key theme was that IPC measures were experienced as "harmful barriers to the experience of receiving and offering care" [11].

- Analyze Themes Using Ethical Theory: This is the core integrative step. Take the emergent empirical themes and analyze them using the concepts and frameworks of relevant ethical theories. The Reset project, for instance, used relational ethical theory to analyze its findings, contrasting the relational reality of care with the atomistic, individual-patient focus of some clinical ethics frameworks [11].

- Refine/Develop Ethical Theory and Generate Normative Suggestions: Based on the analysis, refine the existing ethical theory or develop new normative suggestions that are informed by the empirical data. The conclusion of the Reset project was the normative suggestion that "clinical ethics should explicitly attend to the importance of relationships in clinical practice" and that organizational decision-making should account for the moral significance of caring relationships [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

In empirical bioethics, the "research reagents" are the conceptual tools and frameworks that enable the integration of data and theory.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Empirical Bioethics

| Research 'Reagent' | Function/Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | To collect rich, contextual qualitative data on lived experiences of ethical dilemmas while ensuring key topics are covered. | Exploring healthcare professionals' challenges in balancing visitor restrictions with family-centered care in paediatrics [11]. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., MAXQDA) | To assist in the systematic management, coding, and thematic analysis of qualitative data (interview/focus group transcripts) [1]. | Identifying recurring themes and patterns across a large dataset of interviews, such as the theme of "relational care as an ethical imperative." |

| Established Ethical Frameworks (e.g., Principlism) | To provide the initial normative concepts and vocabulary for analyzing the empirical data. | Using the four principles (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice) as a lens to code ethical conflicts described by participants. |

| Relational Ethical Theory | A theoretical framework that posits individuals are constituted by their networks of relationships, shifting the ethical focus from the atomistic individual [11]. | Arguing for a shift in clinical ethics to acknowledge the "patient-in-relationships" based on data showing the importance of relational interactions in care. |

| Reflective Equilibrium Framework | A methodological tool for testing and achieving coherence between ethical principles, empirical facts, and considered moral judgements [1]. | Revising one's initial normative position on visitor policies after being confronted with empirical data on the negative impacts of isolation. |

Data Presentation and Analysis Protocols

Clear data presentation is crucial for demonstrating the validity of the integration process. This involves both summarizing quantitative or categorical data and transparently outlining the analytical steps for qualitative data.

Table 3: Template for Research Protocol Sections as per Adapted SRQR Guidelines for Empirical Bioethics [12]

| Protocol Section | Key Content to Include | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Title and Abstract | Clearly describe the nature of the study and its empirical-normative approach. | Allows readers to immediately identify the methodological approach of the paper. |

| Problem Studied | Explain the importance of the problem and summarize the most significant existing literature. | Positions the research within the existing scholarly conversation and justifies its necessity. |

| Research Paradigm | Explicitly state and justify the methodological framework (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, mixed) and the theoretical framework (e.g., principlism, relational ethics) for integration [12]. | Provides critical transparency about the epistemological and normative foundations of the study. |

| Data Collection & Instruments | Detail the procedures and instruments used (e.g., interview guides, questionnaires). | Ensures the reliability and allows for the replication of the empirical component. |

| Data Analysis | For qualitative data, specify in sufficient detail how the data will be analyzed (e.g., thematic analysis). For normative analysis, describe the ethical framework applied. | Demonstrates methodological rigor in both the empirical and normative wings of the research. |

| Integration Method | Clearly articulate the chosen method for integration (e.g., symbiotic, reflective equilibrium) and justify its selection. Explain how the method was operationalized. | Addresses the core challenge of vagueness by making the integration process transparent and accountable. |

Untangling normative analysis from empirical data is not an end in itself; rather, it is a necessary step towards their more robust and transparent reintegration. By moving away from vague methodological descriptions and adopting structured protocols like the one detailed herein, researchers in bioethics, science, and drug development can significantly enhance the credibility, impact, and practical utility of their work. The explicit use of frameworks such as symbiotic empirical ethics, coupled with clear data presentation and a well-defined "toolkit" of research reagents, provides a roadmap for navigating the complexities of interdisciplinary research. This structured approach ensures that the resulting normative conclusions are not only philosophically sound but also deeply grounded in the empirical realities of practice.

The growing complexity of modern bioethical challenges, particularly in fast-evolving fields like healthcare artificial intelligence (AI) and drug development, has revealed the limitations of isolated research approaches. Purely philosophical methods risk becoming disconnected from the practical realities and complexities of clinical practice, while merely descriptive empirical approaches often fail to deliver the normative guidance needed for ethical decision-making [13] [7]. This protocol outlines the rationale and methodological framework for integrating normative and empirical approaches within bioethics research, providing researchers with structured pathways to produce findings that are both philosophically robust and empirically grounded.

The impetus for integration stems from recognition that ethical principles must be informed by the actual experiences, values, and constraints of stakeholders—including patients, researchers, clinicians, and drug development professionals [14]. Empirical bioethics has emerged precisely from "a dissatisfaction with a purely philosophical approach, perceived as being insufficient to address bioethical issues" and a belief that "an empirically informed bioethics is better suited to deal with the complexity of human practices" [7]. By systematically bridging these traditionally separate domains, researchers can develop ethical frameworks that are simultaneously conceptually sound, practically applicable, and contextually responsive.

Theoretical Foundations and Integration Rationale

Epistemological Underpinnings

Integrated empirical bioethics operates on the premise that ethical analysis gains validity and practical relevance when informed by systematic observation of real-world contexts, practices, and stakeholder perspectives [7]. This approach acknowledges that ethical dilemmas occur within specific socio-technical environments—such as clinical trials, research laboratories, or healthcare delivery systems—where organizational structures, professional norms, and resource constraints significantly shape moral decision-making.

The integration of normative and empirical components follows two primary epistemological pathways:

- Empirically-Informed Normativity: Empirical data about stakeholder experiences, values, and practices informs and shapes the development of ethical principles and recommendations.

- Normatively-Framed Empiricism: Ethical theories and frameworks guide the collection and interpretation of empirical data, ensuring research addresses morally significant questions.

This bidirectional relationship ensures that ethical analysis remains grounded in actual practices while empirical research addresses normatively significant questions [7]. As one study notes, "empirical research in empirical ethics is not an end in itself, but a required step towards a normative conclusion or statement with regard to empirical analysis, leading to a combination of empirical research with ethical analysis and argument" [7].

Comparative Advantages of Integrated Approaches

Table 1: Comparing Research Approaches in Bioethics

| Approach | Key Characteristics | Strengths | Limitations | Suitable Research Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purely Philosophical | Deductive reasoning from ethical principles; conceptual analysis; limited empirical data | Conceptual clarity; logical consistency; identifies fundamental principles | May overlook practical constraints; potential disconnect from real-world contexts | Foundational ethical principles; conceptual clarification |

| Purely Descriptive | Observation and description of ethical phenomena; quantitative or qualitative data | Identifies actual practices and attitudes; contextual understanding | Limited normative guidance; descriptive rather than prescriptive | Mapping stakeholder perspectives; describing ethical practices |

| Integrated Empirical-Normative | Combines empirical data with ethical analysis; iterative processes | Contextually sensitive ethical guidance; pragmatic relevance; theoretically informed | Methodological complexity; requires interdisciplinary expertise | Developing practice-grounded ethical guidelines; policy formulation |

Methodological Framework and Integration Protocols

Core Integration Methodologies

Based on analysis of current practices in empirical bioethics, three prominent methodological approaches for integration have emerged, each with distinct procedures and applications [7].

Reflective Equilibrium Protocol

The reflective equilibrium approach, particularly in its "wide" form, involves an iterative process of adjustment between ethical principles, empirical findings, and considered moral judgments [7].

Protocol Steps:

- Initial Positioning: Clearly articulate relevant ethical theories, principles, and preliminary moral intuitions regarding the research question.

- Empirical Data Collection: Gather systematic data through methods appropriate to the research context (e.g., interviews, surveys, observational studies).

- Comparative Analysis: Identify points of coherence and tension between ethical principles, empirical findings, and considered moral judgments.

- Iterative Adjustment: Systematically adjust elements to achieve greater coherence, which may involve:

- Revising ethical principles to better account for empirical realities

- Reinterpreting empirical data through different theoretical lenses

- Modifying initial moral judgments in light of conflicting evidence

- Equilibrium Achievement: Establish a reflective equilibrium where principles, data, and judgments achieve maximal coherence.

- Normative Output: Formulate ethical guidance or recommendations based on the achieved equilibrium.

Application Context: Particularly suitable for research questions where established ethical principles require contextual refinement or when empirical findings challenge conventional moral wisdom.

Embedded Ethics Protocol

The Embedded Ethics approach involves integrating ethicists and social scientists directly into research and development teams, particularly in technology-driven domains like healthcare AI and drug development [14].

Protocol Steps:

- Integration Planning: Identify integration points in the research or development lifecycle where ethical input will be most valuable.

- Team Embedding: Position ethicists/social scientists within research teams with access to meetings, documentation, and decision-making processes.

- Continuous Monitoring: Employ ongoing observation and engagement to identify emerging ethical issues during technology development or research progression.

- Iterative Intervention: Introduce ethical analysis at multiple stages rather than solely as a pre- or post-development evaluation.

- Collaborative Deliberation: Facilitate structured discussions between technical experts and ethics researchers to co-develop solutions.

- Documentation and Reflexivity: Maintain detailed records of ethical issues identified, discussions held, and resolutions reached.

Application Context: Particularly valuable in interdisciplinary health research consortia, AI development projects, and innovative drug development where ethical implications emerge throughout the research process [14].

Dialogical Empirical Ethics Protocol

This approach emphasizes stakeholder engagement and dialogue as the primary mechanism for integrating empirical and normative dimensions [7].

Protocol Steps:

- Stakeholder Mapping: Identify all relevant stakeholders for the ethical issue under investigation.

- Empirical Data Collection: Gather initial data on stakeholder perspectives, experiences, and values through interviews, surveys, or observations.

- Structured Dialogue Facilitation: Organize and facilitate deliberative forums where stakeholders engage with ethical principles and empirical findings.

- Iterative Sense-Making: Support participants in collaboratively working through ethical dilemmas and developing shared understandings.

- Normative Refinement: Translate dialogical outcomes into ethical recommendations or frameworks.

- Validation and Feedback: Circulate findings back to stakeholders for confirmation and further refinement.

Application Context: Particularly appropriate for research questions involving diverse value perspectives, policy development, or community-engaged research.

Methodological Toolbox for Integration

Table 2: Empirical Methods for Integrated Bioethics Research

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Data Generated | Integration Function | Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Engagement | Interviews, focus groups, peer-to-peer interviews [14] | Perspectives, values, experiences | Informs ethical analysis with stakeholder viewpoints | Moderate time commitment; ethical approval needed |

| Observational Approaches | Ethnography, participant observation [14] | Contextual practices, organizational cultures | Grounds ethical analysis in actual practices | Significant time investment; researcher training needed |

| Deliberative Methods | Structured workshops, stakeholder dialogues [14] | Reflective judgments, negotiated outcomes | Generates ethical consensus through democratic processes | Facilitation expertise; diverse stakeholder recruitment |

| Analytical Methods | Bias analyses, literature reviews [14] | Systematic identification of ethical issues | Structures ethical assessment using conceptual frameworks | Research expertise; access to literature databases |

Practical Implementation and Research Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Integrated Bioethics Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Integration Application | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Data Analysis | MAXQDA, NVivo [15] | Coding and analysis of textual, audio, visual data | Systematic analysis of interviews, focus groups, documents | Commercial licenses; training required |

| Quantitative Analysis | SPSS, Stata, R [15] [16] | Statistical analysis of numerical data | Analysis of survey data; descriptive and inferential statistics | Various licensing models; R is open-source |

| Mixed Methods Support | MAXQDA 2024 [15] | Integration of qualitative and quantitative data | Combined analysis of diverse data types for richer insights | Commercial license; specialized functionality |

| Data Collection | Qualtrics, LimeSurvey [16] | Survey design and distribution | Efficient gathering of empirical data from multiple participants | Various pricing tiers; cloud-based access |

Integration Workflow Protocol

Application Contexts and Adaptability

The integrated approaches outlined in this protocol have demonstrated particular utility in several bioethics research domains relevant to drug development professionals and health researchers:

Early-Phase Clinical Trials in Oncology

Integrated approaches enable researchers to examine ethical issues surrounding patient participation, informed consent processes, and risk-benefit assessments through combined analysis of stakeholder experiences (empirical) and ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice (normative) [13].

Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

The Embedded Ethics approach has proven valuable in identifying and addressing ethical challenges during the development of AI technologies for healthcare, including issues of algorithmic bias, transparency, and accountability [14]. This enables proactive ethical integration rather than post-hoc analysis.

Genomic Research and Polygenic Risk Scores

Integrated methodologies facilitate examination of ethical implications of genetic risk prediction, including issues of privacy, psychological impact, and justice in access to emerging genomic technologies [14].

Implementation Considerations and Limitations

While integrated empirical-normative approaches offer significant advantages, researchers should acknowledge several implementation challenges:

Methodological Competence

Successful integration requires research teams to possess or develop competence in both empirical research methods and ethical analysis. This often necessitates interdisciplinary collaboration or additional training [7].

Resource Allocation

Integrated approaches typically require more time and resources than single-method studies, particularly for processes like reflective equilibrium that involve iterative analysis or Embedded Ethics requiring long-term engagement [14].

Theoretical and Methodological Transparency

Researchers must clearly articulate and justify their chosen integration methodology, as "the indeterminacy of integration methods is a double-edged sword. It allows for flexibility but also risks obscuring a lack of understanding of the theoretical-methodological underpinnings" [7].

Despite these challenges, the rigorous integration of empirical and normative approaches represents a scientifically robust and ethically responsive pathway for addressing complex bioethical challenges in contemporary health research and drug development.

The application of the four cornerstone principles of bioethics—autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice—is undergoing a significant transformation. Contemporary scholarship emphasizes the necessity of integrating traditional normative analysis with empirical research methodologies to address complex challenges in healthcare and biotechnology [17] [12]. This integrated approach strengthens the foundation for ethical decision-making by grounding theoretical principles in observable data concerning human behaviors, values, and systemic interactions. The burgeoning field of empirical bioethics reflects this synthesis, utilizing methods from social sciences to investigate ethical questions within medical practice and research [18] [12]. This document provides application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in operationalizing the four principles within this integrated framework, with particular attention to emerging technologies and cross-cultural contexts.

Core Principles and Their Operationalization

The Principle of Autonomy

Theoretical Foundation: The principle of autonomy recognizes the intrinsic right of individuals to self-determination and to make decisions about their own lives and bodies without external coercion [19]. This principle provides the ethical foundation for informed consent, truth-telling, and confidentiality in clinical practice and research [19]. Its philosophical roots are often traced to Kant and Mill, emphasizing the unconditional worth of individuals and their capacity for rational decision-making [19].

Applied Contexts and Challenges:

- Informed Consent Protocols: Valid consent requires that the patient or research subject is competent, receives full disclosure, comprehends the information, acts voluntarily, and provides consent [19]. These requirements, while foundational in Western bioethics, may encounter resistance or require adaptation in non-Western cultures that emphasize family-centered or community-centered decision-making [19] [20].

- Relational Autonomy: Critics of a strictly individualistic interpretation of autonomy propose a broader concept of "relational autonomy," acknowledging that decisions are shaped by social relationships, culture, gender, and ethnicity [19].

- Emerging Technology Interface: The digital transformation of healthcare introduces new dimensions to autonomy, involving consent for the use of digital tools, data sharing, and AI-supported care [17]. Empirical studies are crucial for understanding patient preferences and comprehension in these novel contexts.

The Principles of Beneficence and Nonmaleficence

Theoretical Foundation: The principles of beneficence (the obligation to act for the benefit of others) and nonmaleficence (the obligation not to inflict harm, primum non nocere) are among the oldest in medical ethics, traceable to the Hippocratic Oath [19]. Beneficence supports moral rules to protect rights, prevent harm, and help persons with disabilities, while nonmaleficence supports rules against killing, causing pain, or incapacitating others [19].

Applied Contexts and Challenges:

- Risk-Benefit Analysis in Drug Development: A practical application of these principles involves the careful weighing of the benefits of an intervention against its potential burdens and risks [19]. This is central to the design of clinical trials and therapeutic regimens.

- End-of-Life Care: These principles guide difficult decisions regarding withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, medically administered nutrition and hydration, and pain management, where the doctrine of double effect may be applied [19].

- Digital Health and AI: In digital health, beneficence involves using technology to improve health outcomes, while nonmaleficence requires addressing risks like data breaches, algorithmic errors, or the amplification of health disparities [17]. Algorithmic bias represents a significant potential maleficence that requires empirical investigation and mitigation.

The Principle of Justice

Theoretical Foundation: The principle of justice demands fairness in the distribution of benefits, risks, and costs [19]. Philosopher John Rawls's theory, which argues for principles of justice chosen behind a "veil of ignorance," is highly influential in contemporary bioethics [17]. It is crucial to distinguish between equality (treating everyone the same), equity (allocating resources based on circumstance to achieve fair outcomes), and justice (addressing the root causes of inequality and removing structural barriers) [17].

Applied Contexts and Challenges:

- Distributive Justice in Healthcare Access: This concerns the fair allocation of scarce healthcare resources and access to innovative therapies. The failure of "trickle-down equity" in healthcare highlights the need for proactive justice-oriented approaches from the outset of technology development [21].

- Translational Justice: This emerging framework proposes "procedural and outcomes-based attention to how clinical technologies move from bench to bedside in a manner that equitably addresses the values and practical needs of affected community members" [21]. It argues that equity must be integrated from the basic science stage, not as an afterthought.

- Digital Determinants of Health (DDH): Factors such as access to digital infrastructure, digital literacy, and algorithmic bias are increasingly recognized as determinants of health outcomes. Justice requires actively reducing this digital divide through inclusive design and policy [17].

- Global and Cross-Cultural Frameworks: There is a growing movement to augment and enrich the bioethics canon with scholarly work on global frameworks of justice that reach beyond Eurocentric perspectives, particularly for emerging biotechnologies [22] [20].

Quantitative Landscape of Empirical Bioethics Research

Empirical research in bioethics has seen significant growth, providing a data-driven foundation for integrating normative and empirical approaches. The following table summarizes key trends in empirical bioethics publications based on a retrospective study of nine leading journals.

Table 1: Prevalence and Nature of Empirical Research in Bioethics (1990-2003)

| Aspect of Empirical Research | Findings | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Prevalence | 435 of 4,029 articles (10.8%) used an empirical design [18]. | N/A |

| Temporal Trend | Increase from 5.4% in 1990 to 15.3% in 2003. Period 1997-2003 (n=309) had more empirical studies than 1990-1996 (n=126) [18]. | χ² = 49.0264, p < .0001 [18] |

| Leading Journals (by % of empirical articles) | 1. Nursing Ethics (39.5%)2. Journal of Medical Ethics (16.8%)3. Journal of Clinical Ethics (15.4%) [18] | N/A |

| Methodological Paradigm | 64.6% (n=281) employed a quantitative paradigm [18]. | N/A |

| Geographic Distribution of Bioethics Publications | USA (59.3%), UK (13.5%), Canada (4.0%), and Australia (3.8%) dominated publications [23]. | Significant decrease in U.S. contribution from 1997-2003 (χ² = 90, p < .0001) [23] |

Table 2: Key Research Topics in Empirical Bioethics

| Research Topic | Frequency | Representative Research Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Prolongation of Life and Euthanasia | 68 studies (Most frequent topic) [18] | Patients, healthcare providers |

| Patient Autonomy & Informed Consent | Numerous studies [18] [20] | Patients, surrogates |

| Cross-Cultural Understanding of Principles | Numerous studies [20] | Medical professionals, general public across different countries |

Experimental Protocols for Empirical Bioethics

General Protocol Template for Empirical Bioethics Research

The following protocol template, adapted for humanities and social sciences in health, is suitable for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research in empirical bioethics [12].

Table 3: Core Sections of an Empirical Bioethics Research Protocol

| Section Number | Section Title | Key Content Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Title, short title and acronym | Concisely describe the nature and subject of the study and the methodological approach [12]. |

| 6 | Summary | Summarize the study's context, primary objective, and general method without bibliographic references [12]. |

| 7 | Problem studied | Explain the importance of the problem and summarize the most significant existing works [12]. |

| 8 | Objective(s) of the study | Present the specific research objectives and/or questions [12]. |

| 9 | Disciplinary field | Specify the principal disciplinary field(s) (e.g., empirical bioethics, medical anthropology) [12]. |

| 10 | Research paradigm of the study | Critical Section: Specify the methodological framework (qualitative/quantitative/mixed) and the theoretical normative framework (e.g., principlism, specific theory of justice) used to derive normative conclusions from empirical data [12]. |

| 12 | Characteristics of the investigator(s) | Specify investigator qualifications, experience, and potential relationships to participants that could bias the study [12]. |

| 13 | Characteristics of the participants/populations | Specify the characteristics of the study participants and the sample size justification [12]. |

| 15 | Consent and information | Specify and justify the type of informed consent and information notice used [12]. |

| 16 | Data collection | Present and justify the types of data, procedures, and instruments (e.g., interview guides, questionnaires) [12]. |

| 19 | Data analysis | Present and justify the analytical methods, including techniques for qualitative and/or quantitative data [12]. |

Workflow for an Integrated Normative-Empirical Study

The following diagram illustrates the sequential and iterative workflow for conducting a study that integrates empirical research with normative analysis.

Protocol for Evaluating AI in Medical Ethics Contexts

With the increasing use of artificial intelligence, empirical protocols are needed to evaluate its alignment with bioethical principles. The following methodology is adapted from a study on human-machine agreement in patient autonomy cases [24].

Objective: To evaluate and improve the alignment of Large Language Models (LLMs) with physician consensus on hypothetical cases involving patient autonomy.

Methodology:

- Case Development: Compose a set of hypothetical cases (e.g., 44 cases) covering key areas like capacity to consent, treatment refusal, and confidentiality. No real patient information should be used [24].

- Physician Panel: Establish a panel of board-certified physicians (e.g., 5 physicians) to establish a consensus (majority response) for each case [24].

- Evaluation Phase: Present cases to foundational LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT, LLaMA, Gemini) and compare their yes/no responses to the physician consensus using Cohen's κ statistic [24].

- Improvement Phase: Iteratively use prompt engineering techniques (e.g., chain-of-thought, N-shot prompting, question-refinement) to improve LLM responses. The goal is to achieve statistically significant improvement in agreement with the physician consensus, measured by the McNemar test [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key methodological "reagents" and their functions for designing and implementing robust empirical bioethics research.

Table 4: Essential Methodological Tools for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Tool / Method | Function / Application | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Surveys & Questionnaires | Quantitatively measure attitudes, beliefs, and experiences of stakeholders (patients, providers, public) regarding ethical issues. | Requires rigorous development, validation, and cross-cultural adaptation for international studies [18] [20]. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | Facilitate in-depth, qualitative exploration of lived experiences, values, and ethical reasoning behind decisions. | Guides should be piloted. Interviewers require training to minimize bias [18] [12]. |

| Hypothetical Vignettes | Present standardized ethical scenarios to study decision-making patterns and evaluate interventions (e.g., AI ethics tools) under controlled conditions [24]. | Fidelity and realism of vignettes are critical for ecological validity. |

| Standardized Protocol Template | Provides a structured framework for planning, documenting, and ensuring rigor in humanities and social science health research [12]. | Must be flexible enough to accommodate diverse methodological and epistemological approaches [12]. |

| Cross-Cultural Comparative Framework | Systematically analyze and compare the interpretation and application of ethical principles across different cultural and national contexts [20]. | Must account for linguistic nuances, local norms, and dominant religious/philosophical traditions [20]. |

| Prompt Engineering Techniques (for AI Ethics) | A set of methods (e.g., chain-of-thought, role-playing) to improve the reliability and ethical alignment of LLM responses in bioethics tasks [24]. | Requires human expert oversight and validation against a gold standard (e.g., physician consensus) [24]. |

The integration of normative analysis with empirical research methodologies represents the forefront of modern bioethics. By systematically applying the principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice through the protocols, tools, and frameworks outlined in this document, researchers and drug development professionals can generate robust, actionable evidence to guide ethical practice. This approach is essential for navigating the complex ethical terrain of digital health, biotechnology, and global health inequities, ensuring that advancements in medicine remain firmly rooted in a commitment to human dignity and justice. Future work must continue to broaden the scope of justice frameworks beyond traditional Western canon and refine empirical methods for capturing the nuanced reality of ethical decision-making in diverse contexts.

Application Note: Empirical Data and Normative Analysis in Clinical Research Appraisal

Background and Quantitative Landscape

The integration of empirical data with normative analysis begins with understanding the landscape of scientific commentary in clinical research. Analysis of PubMed data reveals that only 4.65% of published clinical research articles receive post-publication comments, with a total of 171,556 unique comments on 130,629 unique clinical studies [25]. This commentary ecosystem represents a crucial interface where empirical evidence meets interpretive, normative judgment.

Table 1: Characterization of Scientific Commentary on Clinical Research Studies

| Aspect | Overall Data | Editorials | Letters to Editor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Comments | 171,556 | 46,644 | 85,252 |

| Commented Articles | 130,629 | 48,370 | 62,919 |

| Temporal Distribution (2015-2018) | 29,027 comments (16.92%) | 7,442 comments (15.95%) | 12,494 comments (14.66%) |

| Supportive Tone Prevalence | 67% (from sample) | N/A | N/A |

| Top Journal (Frequency) | The New England Journal of Medicine (4.94% of comments) | The New England Journal of Medicine (4.25% of comments) | The New England Journal of Medicine (7.32% of comments) |

Protocol for Evidence Appraisal Integration

Objective: To establish a systematic methodology for integrating empirical clinical research findings with normative ethical analysis through critical commentary assessment.

Materials:

- PubMed/MEDLINE database access

- Citation management software (e.g., EndNote, Zotero)

- Qualitative data analysis tool (e.g., MAXQDA, NVivo)

- Ethical framework selection guide

Procedure:

- Identification: Query PubMed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for clinical studies with comments via "hascommentin" filter [25]

- Metadata Extraction: Collect PubMed IDs, publication types, dates, journal names, and MeSH terms for articles and corresponding comments

- Full-Text Acquisition: Retrieve complete comments through NCBI Entrez Programming Utilities, PMC Open Access, and non-PMC journals with OA policies

- Content Analysis: Apply Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling with Gibbs sampling to identify dominant themes

- Sentiment Coding: Manually classify comments as "generally supportive," "neutral," or "generally critical" with interrater reliability assessment

- Normative Framework Application: Select appropriate ethical theories using adequacy, suitability, and theoretical background criteria [26]

- Integration: Employ reflective equilibrium or dialogical methods to synthesize empirical findings with normative analysis

Deliverables: Critical appraisal report with empirical summary and normative recommendations, thematic analysis of commentary patterns, and ethical guidance for clinical implementation.

Application Note: Normative-Empirical Integration in Biopharmaceutical Policy

Empirical Foundation for Policy Analysis

Biopharmaceutical policy represents a critical application area where empirical data on research and development (R&D) investment must inform normative decisions about drug pricing, innovation incentives, and public health priorities. Current policy models, including those used by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), rely on outdated data that fail to capture complexities of modern drug development [27]. The relationship between financial returns and R&D investment demonstrates that $2.5 billion in additional revenue is needed to invent one new chemical entity, and a 1% increase in potential market size leads to a 4-6% increase in new drugs in that therapeutic area [27].

Table 2: Biopharmaceutical Policy Analysis Framework

| Policy Challenge | Current Data Limitations | Empirical Needs | Normative Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of price-setting | Outdated models; lack of analogs for US market | Updated investment data across therapeutic areas | Balance between immediate savings and future health benefits |

| Therapeutic area disparities | Shift to oncology not fully captured | Therapeutic area-specific impact analyses | Equity in drug development for rare diseases and common conditions |

| Post-market development | Overlooks R&D for existing drugs | Data on new indications and combination therapies | Patient access to improved treatments |

| Emerging modalities | Limited data on cell/gene therapies | Investment patterns in novel technologies | Just allocation of resources for transformative treatments |

| Global implications | US-centric models | International investment flow data | Global health equity and burden-sharing |

Protocol for Policy Impact Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the normative implications of biopharmaceutical policies using empirical data on R&D investment and clinical development outcomes.

Materials:

- Federal and private biopharmaceutical development datasets

- Investment trend analysis software

- Policy modeling tools

- Therapeutic area classification system

Procedure:

- Data Aggregation: Compile data on R&D investment, clinical trial outcomes, and market returns from FDA records, clinical trial registries, and industry reports

- Therapeutic Area Stratification: Analyze investment patterns across oncology, rare diseases, vaccines, and emerging modalities (gene/cell therapies)

- Policy Scenario Modeling: Project impacts of price regulations, intellectual property changes, and reimbursement policies on R&D investment

- Stakeholder Analysis: Identify varying risk tolerance among investors, large pharmaceutical companies, and small biotech firms

- Normative Framework Selection: Apply adequacy criteria to select ethical theories addressing justice, equity, and innovation incentives [26]

- Integration Methodology: Implement reflexive balancing between empirical data and normative principles [1]

- Impact Quantification: Estimate effects on new drug development, patient access, and global health outcomes

Deliverables: Policy impact assessment report, therapeutic area-specific investment recommendations, and ethical framework for balancing innovation incentives with affordability concerns.

Visualization: Integration Methodology for Empirical-Normative Research

Diagram 1: Empirical-Normative Integration Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Empirical-Normative Bioethics Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE Database | Identification of clinical studies and scientific commentary | Evidence base characterization and commentary analysis [25] |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software | Topic modeling and content analysis of textual data | Identifying themes in scientific commentary and policy documents [25] |

| Ethical Framework Selection Guide | Systematic approach to choosing normative theories | Ensuring adequacy, suitability, and theoretical coherence [26] |

| Reflective Equilibrium Methodology | Structured process for normative-empirical integration | Balancing empirical data with ethical principles through iterative reflection [1] |

| Policy Modeling Tools | Projecting impacts of regulatory changes on innovation | Analyzing effects of price-setting on drug development investment [27] |

| Stakeholder Engagement Framework | Incorporating diverse perspectives in analysis | Ensuring inclusive dialogical empirical ethics approaches [1] |

Application Note: Methodological Approaches for Integration

Theoretical Foundations

The integration of empirical and normative approaches requires careful methodological consideration. Empirical bioethics centers around the integration of empirical findings with normative philosophical analysis, but the process often remains unclear despite numerous available methodologies [1]. Three primary methodological approaches have been identified: (1) consultative, where researchers independently analyze data to develop normative conclusions (e.g., reflexive balancing, reflective equilibrium); (2) dialogical, relying on stakeholder dialogue to reach shared understanding (e.g., inter-ethics); and (3) combined approaches that integrate both methods [1].

Protocol for Reflective Equilibrium Integration

Objective: To implement Wide Reflective Equilibrium as a methodology for integrating empirical data with normative analysis.

Materials:

- Empirical research findings

- Documented moral intuitions and principles

- Background ethical theories

- Iterative analysis framework

Procedure:

- Empirical Premise Formation: Collect and analyze relevant empirical data (e.g., clinical research patterns, investment trends)

- Normative Premise Articulation: Identify relevant moral principles, values, and ethical theories for the research question

- Initial Considered Judgments: Document reasoned moral intuitions about specific cases

- Iterative Reconciliation: Systematically move back and forth between empirical data, ethical principles, and considered judgments

- Coherence Assessment: Evaluate whether all elements form a coherent network of beliefs

- Equilibrium Achievement: Reach temporary equilibrium where all elements support one another

- Application: Apply the achieved equilibrium to the specific research question or case

Deliverables: Reflective equilibrium report documenting the iterative process, identified points of tension and resolution, and normative conclusions supported by empirical evidence.

The scope of application from clinical research to biopharmaceutical policy and public health demonstrates the critical importance of integrating empirical data with normative analysis. This integration requires systematic methodologies that make the selection of ethical frameworks transparent and the process of combining empirical findings with normative reasoning explicit. Through structured approaches like reflective equilibrium and dialogical ethics, researchers can develop more robust, justified conclusions that advance both scientific understanding and ethical practice in medicine and health policy.

Methodologies in Action: Selecting Frameworks and Applying Integrative Models

Empirical bioethics is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to integrate empirical findings with normative (philosophical) analysis to draw substantive conclusions about how we ought to act in healthcare and life sciences contexts [7] [28]. This integration is particularly crucial for drug development professionals and researchers who must navigate complex ethical terrain that spans basic science, clinical research, clinical care, and public health [29]. Despite the availability of numerous methodological approaches, the process of integration often remains opaque and challenging, with researchers reporting an "air of uncertainty and overall vagueness" about how to effectively combine empirical data with normative reasoning [7]. This application note provides structured guidance on three prominent methodological approaches, complete with practical protocols and visual frameworks designed for immediate application in research settings.

Methodological Frameworks: Principles and Applications

The table below summarizes three principal methodologies employed in empirical bioethics research, each offering distinct approaches to integrating empirical observations with normative analysis.

Table 1: Core Methodologies in Empirical Bioethics Research

| Methodology | Primary Integration Mechanism | Typical Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective Equilibrium | Back-and-forth adjustment between principles and judgements [7] [30] | Policy development, ethical analysis of clinical guidelines [7] | Researcher-driven deliberation; seeks coherence across beliefs; can be narrow (principles-judgements) or wide (includes background theories) [30] |

| Dialogical Models | Structured stakeholder dialogue [7] | Technology ethics, clinical ethics consultation, guideline development [7] [31] | Collaborative deliberation; ethicist as facilitator; generates shared understanding [7] |

| Grounded Moral Analysis | Systematic analysis of empirical data to identify and refine ethical concepts [7] | Research ethics, emerging technology ethics, clinical practice ethics [7] | Inductive approach; moral concepts emerge from data; iterative data collection and analysis [7] |

Reflective Equilibrium: Protocol and Application

Reflective Equilibrium (RE), particularly in its "wide" form, represents a sophisticated approach to ethical justification that extends beyond mere coherence-seeking to aim for systematic coherence among an interconnected network of commitments [30]. The methodology is characterized by its iterative process of adjustment between considered judgments about particular cases and ethical principles, seeking mutual alignment and support.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Wide Reflective Equilibrium

Research Question Formulation

- Define the specific ethical problem or question requiring normative guidance

- Example: "What ethical framework should guide the use of gamification in digital mental health technologies for adolescents?" [31]

Initial Commitment Elicitation

- Document considered judgments: Gather pre-theoretical ethical intuitions about specific cases or scenarios

- Articulate relevant principles: Identify applicable ethical principles (e.g., autonomy, beneficence, justice)

- Identify background theories: Note relevant philosophical, political, or scientific theories that inform the domain

Process of Equilibration

- Test principles against judgments: Assess whether principles consistently generate the considered judgments in specific cases

- Identify discrepancies: Note where principles and judgments conflict or where judgments are inconsistent

- Revise and refine: Make adjustments to principles, judgments, or background theories to eliminate inconsistencies

- Seek systematic coherence: Aim for relationships of mutual support across the belief network, not mere consistency

Equilibrium Assessment

- Evaluate whether the revised set of commitments provides a defensible, coherent framework that justifies the normative conclusions

- Assess whether the framework satisfies epistemic virtues such as explanatory power, simplicity, and fruitfulness [30]

The following diagram illustrates this iterative process:

Diagram 1: Reflective Equilibrium Iterative Process

Dialogical Models: Protocol and Application

Dialogical empirical ethics relies on structured dialogue between stakeholders to reach a shared understanding of ethical issues and collaboratively develop normative guidance [7]. This approach is particularly valuable in contexts involving multiple perspectives or where ethical analysis benefits from direct engagement with lived experience.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Dialogical Integration

Stakeholder Identification and Recruitment

- Identify all relevant stakeholder groups (patients, clinicians, researchers, industry representatives, etc.)

- Ensure diverse representation within stakeholder groups

- Obtain informed consent for participation, clarifying the normative (not just research) nature of the dialogue

Dialogue Facilitation

- Establish dialogue ground rules emphasizing respect, confidentiality, and open exchange

- Deploy facilitation techniques that ensure equitable participation

- Frame discussion around concrete cases or scenarios to ground abstract principles

- Encourage explicit articulation of values and reasoning

Iterative Dialogue Process

- Initial value exploration: Elicit stakeholder perspectives without imposing theoretical frameworks

- Principle articulation: Collaboratively identify and define relevant ethical principles

- Case-principle testing: Examine how principles apply to specific cases

- Normative refinement: Jointly refine principles and judgments through discussion

Consensus Building

- Identify areas of agreement and disagreement

- Work toward shared normative conclusions when possible

- Document persistent disagreements and their foundations

The following diagram illustrates the collaborative structure of dialogical models:

Diagram 2: Dialogical Model Collaborative Structure

Grounded Moral Analysis: Protocol and Application

Grounded moral analysis employs a systematic, inductive approach to ethical analysis where moral concepts and frameworks emerge from empirical data rather than being imposed upon it [7]. This approach is particularly valuable when investigating novel ethical territories or when seeking to avoid premature theoretical closure.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Grounded Moral Analysis

Data Collection Design

- Employ qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups, observations) appropriate to the research question

- Develop data collection instruments that allow ethical dimensions to emerge naturally

- Include diverse participants to capture a range of moral perspectives

Iterative Data Analysis

- Initial coding: Identify and label morally relevant concepts in the data

- Axial coding: Group initial codes into broader ethical categories and themes

- Theoretical coding: Develop relationships between categories to build a conceptual framework

- Constant comparison: Continuously compare new data with emerging framework

Normative Framework Development

- Refine ethical concepts through iterative data collection and analysis

- Develop substantive ethical positions grounded in the data

- Test emerging framework against new cases or data

Integration and Validation

- Assess coherence and justifiability of the grounded framework

- Examine relationship with existing ethical theories

- Refine framework to address discrepancies or limitations

Standards of Practice in Empirical Bioethics

The consensus on standards of practice in empirical bioethics research provides crucial guidance for ensuring methodological rigor [28]. The table below summarizes key standards across six domains of research practice.

Table 2: Empirical Bioethics Standards of Practice

| Domain | Standard | Application Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Aims | Clearly articulate the aims of the research and its intended contribution | Distinguish between conceptual, instrumental, and symbolic aims; specify intended normative outcomes [28] |

| Questions | Formulate research questions that reflect the interdisciplinary nature of the project | Ensure questions require both empirical and normative analysis; avoid reduction to purely empirical or purely normative questions [28] |

| Integration | Justify the method of integration and demonstrate its execution | Select appropriate integration method (e.g., RE, dialogical, grounded); document how empirical and normative elements interact [7] [28] |

| Empirical Work | Design and conduct empirical work to bioethics standards | Meet quality standards of social science research; ensure methodological appropriateness for normative aims [28] |

| Normative Work | Design and conduct normative work to bioethics standards | Employ rigorous normative methodologies; articulate and justify normative frameworks [28] |

| Training & Expertise | Ensure research team possesses appropriate interdisciplinary expertise | Include both empirical and normative expertise; foster mutual understanding across disciplinary divides [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key methodological "reagents" essential for conducting rigorous empirical bioethics research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Empirical Bioethics

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-structured Interview Guides | Elicit rich qualitative data on moral experiences and reasoning | Include open-ended questions; allow follow-up probes; pilot-test for clarity [7] |

| Case Vignettes | Present concrete scenarios for ethical analysis | Ensure relevance to research question; systematically vary key parameters; maintain realism [7] |

| Deliberative Dialogue Frameworks | Structure stakeholder engagement | Establish ground rules; define facilitator role; create balanced participant mix [7] [28] |

| Coding Manuals | Systematize qualitative data analysis | Define code definitions; establish inclusion/exclusion criteria; ensure intercoder reliability [7] |

| Normative Analysis Frameworks | Structure ethical reasoning and argumentation | Apply established frameworks (e.g., principlism) or develop grounded frameworks; ensure logical rigor [29] [28] |

| Integration Protocols | Guide the combining of empirical and normative elements | Specify sequence and weighting of empirical and normative components; document adjustment processes [7] [28] |

Application Contexts in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The methodological approaches outlined above find specific application across multiple domains of pharmaceutical research and development:

Clinical Trials Ethics

- Application of reflective equilibrium to balance competing ethical principles in trial design

- Dialogical engagement with patients, researchers, and regulators to establish ethically sound protocols

- Grounded analysis of participant experiences to identify previously unrecognized ethical issues [32]

Data Ethics and Digital Health

- Normative framework development for emerging technologies using wide reflective equilibrium

- Stakeholder dialogue addressing ethical tensions in data use, privacy, and benefit-sharing [33]

- Grounded moral analysis of developer perspectives on ethical challenges in digital mental health [31]

Biopharmaceutical Bioethics

- Specification of ethical principles for industry contexts through deliberative processes

- Development of ethics roadmaps for iterative technology development projects [29] [31]

- Ethical analysis spanning research, development, supply, commercialization, and clinical use of healthcare products [29]

The landscape of methods in empirical bioethics offers diverse yet complementary approaches to integrating empirical research with normative analysis. Reflective equilibrium provides a rigorous framework for individual researcher deliberation, dialogical models leverage collective wisdom through structured engagement, and grounded moral analysis ensures ethical frameworks remain connected to lived experience. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering these methodologies enables more nuanced and effective navigation of the complex ethical challenges inherent in pharmaceutical research and development. By adhering to established standards of practice and selecting methodologies appropriate to their specific research questions, bioethics researchers can produce work that is both empirically robust and normatively defensible, ultimately contributing to more ethical healthcare innovation.

The integration of normative ethical analysis with empirical data is a cornerstone of contemporary bioethics research, particularly in fields like healthcare artificial intelligence (AI) and clinical drug development. This interdisciplinary approach, often termed Embedded Ethics or empirical bioethics, relies on the collaboration between ethicists, social scientists, and domain specialists to address ethical and social challenges as they emerge during research and development processes [14]. The core challenge lies in selecting an ethical theory that is both philosophically adequate and contextually suitable, while also being capable of productive interrelation with empirical data to generate normative conclusions. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in this critical selection process, framed within the broader thesis that robust bioethics requires a synergistic, rather than parallel, approach to normative and empirical inquiry.

Foundational Concepts and Selection Criteria

Defining Adequacy and Suitability

The selection of an ethical theory for a bioethics research project should be guided by two principal criteria: adequacy and suitability.

- Adequacy refers to the theory's conceptual robustness and its capacity to address the normative dimensions of the research problem. An adequate theory provides a coherent framework for identifying, analyzing, and justifying moral principles and conclusions [34].

- Suitability concerns the theory's practical fit for the specific research context, including the domain of application (e.g., pragmatic clinical trials, AI in healthcare), the nature of the empirical data to be collected, and the intended outcome of the research (e.g., practical recommendations, conceptual framework) [7].

The interrelation with empirical data is the dynamic process through which the selected ethical theory and the gathered data inform and refine one another. This is not a sequential process but an iterative dialogue, essential for grounding normative analysis in the reality of human practices and experiences [7].

Major Ethical Theories and Their Application

Bioethics research often draws upon several established normative theories. The table below summarizes the key features, strengths, and weaknesses of three major approaches, providing a basis for initial theory selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Ethical Theories in Bioethics Research

| Feature | Utilitarianism | Deontology | Virtue Ethics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Consequences of actions [34] | Duties and rules [34] | Character of the moral agent [34] |

| Key Principle | Greatest happiness principle [34] | Categorical imperative [34] | Cultivation of virtues [34] |

| Notable Philosophers | Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill [34] | Immanuel Kant [34] | Aristotle, Elizabeth Anscombe [34] |