Bridging the Divide: Practical Strategies for Overcoming Interdisciplinary Challenges in Bioethics Methodology

This article addresses the critical methodological challenges faced by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals when navigating the interdisciplinary landscape of modern bioethics.

Bridging the Divide: Practical Strategies for Overcoming Interdisciplinary Challenges in Bioethics Methodology

Abstract

This article addresses the critical methodological challenges faced by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals when navigating the interdisciplinary landscape of modern bioethics. As emerging technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI) and biotechnology rapidly transform biomedical research, traditional ethical frameworks are often outpaced. This piece provides a comprehensive guide, moving from foundational concepts like principlism and casuistry to applied methods such as the Embedded Ethics approach. It offers practical solutions for troubleshooting pervasive issues like algorithmic bias and a lack of transparency, and validates these strategies through real-world case studies and comparative analysis of ethical frameworks. The goal is to equip researchers with the tools to integrate robust, interdisciplinary ethical analysis directly into their research and development lifecycle, fostering responsible innovation that aligns with both scientific and societal values.

The Roots of the Rift: Understanding Core Interdisciplinary Tensions in Bioethics

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Interdisciplinary Bioethics Methodology

This technical support center provides "troubleshooting guides" for researchers navigating the complex methodological challenges inherent in interdisciplinary bioethics research. The following FAQs address specific issues you might encounter, framed within the broader thesis of overcoming interdisciplinary barriers to strengthen methodological rigor.

Frequently Asked Questions and Troubleshooting Guides

1. FAQ: How do I resolve conflicting conclusions arising from different disciplinary methods in my bioethics research?

- Issue Description: Your research team includes members from philosophy, law, and sociology. Each applies their own disciplinary methods to a common research question (e.g., the ethics of genomic data sharing) and arrives at different, sometimes conflicting, normative conclusions. There is no agreed-upon standard to evaluate which conclusion is most valid [1].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Diagnose the Root Cause: Acknowledge that this conflict often stems from differing, often implicit, disciplinary standards of "rigor" and "validity" [1]. Philosophy may prioritize logical coherence, law may focus on precedent, and sociology may value empirical data.

- Isolate the Methodological Assumptions: Facilitate a team discussion to explicitly articulate the methodological assumptions and standards of evidence from each discipline. This makes the sources of conflict visible.

- Implement an Interdisciplinary Framework: Move beyond a simple multidisciplinary model (where disciplines work in parallel) towards an interdisciplinary one. Actively work to integrate perspectives, creating a synthesized analytical framework that acknowledges the strengths and limitations of each approach [1] [2]. The goal is not to find one "correct" answer, but to develop a more robust, nuanced understanding that is informed by multiple ways of knowing.

- Preventative Measures for Future Research: Establish a shared methodological framework at the project's inception. This framework should define how different types of evidence will be weighed and integrated to form normative conclusions.

2. FAQ: How can I ensure my interdisciplinary bioethics research is perceived as rigorous and credible during peer review?

- Issue Description: You are submitting a paper to a journal and are concerned that peer reviewers from a single discipline may dismiss your work as lacking rigor because it does not conform to their specific methodological standards [1].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Gather Contextual Information: Proactively identify potential points of methodological criticism by seeking feedback from colleagues representing each of the disciplines involved in your research before submission.

- Reproduce the Issue for Scrutiny: In the manuscript itself, explicitly justify your interdisciplinary approach. Detail the methods used from each discipline and explain how their integration strengthens the research, rather than obscuring it.

- Apply a Cross-Disciplinary Fix: Frame your work's contribution in terms that are recognized across disciplines, such as its "originality, quality, value, and validity," while carefully defining these terms within your interdisciplinary context [1].

- Solution for Widespread Impact: Advocate for and contribute to the development of field-wide standards for interdisciplinary rigor in bioethics. Support journals in recruiting interdisciplinary reviewer panels.

3. FAQ: My research team is struggling to make practical ethical recommendations for our clinical partners. Our theoretical analysis seems disconnected from the realities of the clinic. What is wrong?

- Issue Description: The ethical guidance your team has developed is theoretically sound but is failing to gain traction or provide practical decision-making support in a fast-paced clinical setting [1].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Practice Active Listening: Engage with clinical partners not just as subjects of study, but as collaborators. Spend time in the clinical environment to understand the pressures, constraints, and practical dilemmas they face daily.

- Ask Effective, Targeted Questions: Instead of asking purely theoretical questions, focus on context-specific ones. For example: "What specific information would be most helpful for you at the moment of decision?" or "What are the operational barriers to implementing this guidance?"

- Develop a Practical Workaround: Use empirical methods from the social sciences (e.g., qualitative interviews, ethnographic observation) to ground your normative analysis in the actual experiences and values of stakeholders [2]. This helps minimize biases like exceptionalism and reductionism, creating recommendations that are both ethically robust and practically applicable [2].

- Final Resolution: Co-design clinical ethics tools or guidelines with end-users (clinicians, patients, administrators) to ensure the output of your research is usable and directly addresses a documented need.

Experimental Protocol: An Interdisciplinary Methodology for Empirical Bioethics

This protocol outlines a structured approach for integrating empirical social science data with philosophical analysis to produce ethically robust and contextually relevant outputs.

1. Problem Identification & Team Assembly

- Objective: Define a pressing clinical ethics issue and assemble an interdisciplinary team.

- Materials: Experts from bioethics (philosophical), social science (e.g., sociology, anthropology), and clinical practice (medicine, nursing).

- Methodology:

- Hold a preliminary meeting to define the research question from multiple disciplinary viewpoints.

- Formally document the anticipated contributions and methodological standards from each discipline.

2. Empirical Data Collection & Analysis

- Objective: Gather qualitative data on stakeholder experiences and values.

- Materials: Interview guides, recording equipment, qualitative data analysis software.

- Methodology:

- Conduct semi-structured interviews or focus groups with relevant stakeholders (e.g., patients, clinicians).

- Transcribe interviews and analyze the data using established qualitative methods (e.g., thematic analysis) to identify key themes, values, and practical conflicts.

3. Normative-Philosophical Integration

- Objective: Integrate empirical findings into a structured ethical analysis.

- Materials: Output from Step 2 (empirical themes), philosophical frameworks (e.g., principlism, casuistry, virtue ethics).

- Methodology:

- Interpret the identified empirical themes through relevant philosophical frameworks.

- Critically assess how the lived reality of the clinic challenges, refines, or strengthens abstract ethical principles.

- Formulate ethical recommendations that are both philosophically sound and empirically grounded.

4. Output Co-Design & Dissemination

- Objective: Create and share a usable output.

- Materials: Draft recommendations, workshop materials.

- Methodology:

- Present the draft recommendations to a group of stakeholder representatives.

- Use a workshop format to refine the output based on feedback regarding its clarity, feasibility, and usefulness.

- Disseminate the final product through academic channels and tailored formats for practice (e.g., clinical guidelines, decision-making tools).

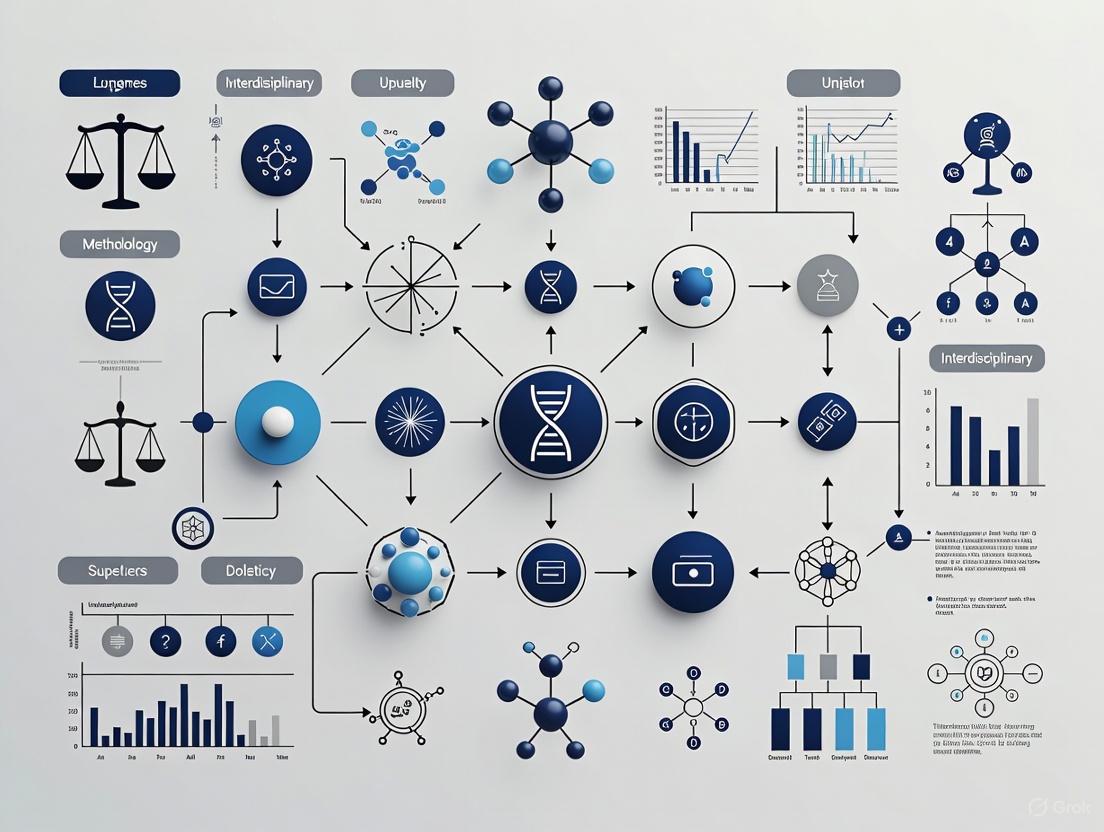

Visualizing the Interdisciplinary Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the empirical bioethics methodology, showing how different disciplinary contributions interact throughout the process.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Interdisciplinary Bioethics

The table below details key conceptual "reagents" and their functions in interdisciplinary bioethics research.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Qualitative Interview Guides | A structured protocol used to gather rich, narrative data on stakeholder experiences, values, and reasoning, grounding ethical analysis in empirical reality [2]. |

| Philosophical Frameworks | Conceptual tools (e.g., Principlism, Virtue Ethics) that provide a structured language and logical system for analyzing moral dilemmas and constructing normative arguments [1]. |

| Legal & Regulatory Analysis | The systematic review of statutes, case law, and policies to understand the existing normative landscape and legal constraints surrounding a bioethical issue [2]. |

| Collaborative Governance Model | A project management structure that explicitly defines roles for all disciplinary experts and stakeholders, ensuring equitable integration of perspectives from start to finish [2]. |

| Bias Mitigation Strategies | Deliberate techniques (e.g., reflexive journaling, devil's advocate) used to identify and challenge disciplinary biases like exceptionalism or reductionism within the research team [2]. |

Bioethics research inherently involves integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives, from philosophy and medicine to law and sociology [1]. This interdisciplinary nature creates methodological challenges, as there is no single, agreed-upon standard of rigor for evaluating ethical questions [1]. Researchers and clinicians must navigate these complexities when addressing moral dilemmas in biomedical contexts. This technical support framework provides structured guidance for applying three foundational ethical theories—Utilitarianism, Deontology, and Virtue Ethics—to practical research scenarios, thereby promoting methodological consistency and rigorous ethical analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Ethical Concepts

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between these three major ethical theories?

- Virtue Ethics focuses on the agent or person, emphasizing character and the pursuit of moral excellence (arete) through virtues. It answers the question, "Who should I be?" [3].

- Deontology focuses on the act itself, concerned with moral duties, rules, and obligations regardless of consequences. It is rooted in principles like Kant's categorical imperative [3] [4].

- Utilitarianism (a form of consequentialism) focuses on the outcome or consequences of an action. It seeks to maximize happiness and minimize pain for the greatest number of people [3] [4].

Q2: How does the principle of justice manifest differently across these theories?

Q3: Can these ethical frameworks be combined in practice? Yes, in practice, these frameworks are often combined. Principlism in bioethics, for example, integrates aspects of these theories into a practical framework built on autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice [4]. The challenge lies in balancing these perspectives, such as weighing deontology's patient-centered duties against utilitarianism's society-centered outcomes during a public health crisis [4].

Ethical Theory Troubleshooting Guide

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common ethical problems in biomedical research.

Problem: A conflict arises between patient welfare and collective public health interests.

| Ethical Theory | Diagnostic Questions | Proposed Resolution Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Utilitarianism | - Which action will produce the best overall consequences?- How can we maximize well-being for the largest number of people?- Does the benefit to the majority outweigh the harm to a minority? | 1. Calculate the potential benefits and harms for all affected parties.2. Choose the course of action that results in the net greatest good. |

| Deontology | - What are my fundamental duties to this patient?- Does this action respect the autonomy and dignity of every individual?- Am I following universally applicable moral rules? | 1. Identify core duties (e.g., to tell the truth, not to harm).2. Uphold these duties, even if doing so leads to suboptimal collective outcomes. |

| Virtue Ethics | - What would a compassionate and just researcher do?- How can this decision reflect the character of a good medical professional?- Which action contributes to my eudaimonia (flourishing) as an ethical person? | 1. Reflect on the virtues essential to your role (e.g., integrity, empathy).2. Act in a way that embodies those virtues. |

Problem: Determining informed consent protocols for vulnerable populations.

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing an Ethical Dilemma

This protocol provides a systematic methodology for analyzing ethical dilemmas in biomedical research, ensuring a structured and interdisciplinary approach.

Materials and Reagents

Table: Essential Materials for Ethical Analysis

| Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Case Description Document | Provides a detailed, factual account of the ethical dilemma for analysis. |

| Stakeholder Map | Identifies all affected individuals, groups, and institutions and their interests. |

| Ethical Frameworks Checklist | A list of core questions from Utilitarian, Deontological, and Virtue Ethics perspectives. |

| Regulatory and Legal Guidelines | Reference materials (e.g., Belmont Report, Declaration of Helsinki) to ensure compliance [4] [5]. |

Methodology

- Case Formulation: Write a precise, neutral description of the case, outlining the facts, context, and the specific ethical conflict.

- Stakeholder Mapping: Identify all parties affected by the decision. For each stakeholder, note their interests, rights, and potential harms/benefits.

- Multi-Theoretical Analysis: Analyze the case sequentially through the lens of each ethical theory using the questions in the troubleshooting guide.

- Resolution Weighing: List potential resolutions. For each resolution, summarize the arguments for and against it based on the three ethical analyses.

- Reflective Equilibrium: Seek a coherent judgment by going back and forth between the case details, the ethical principles, and the proposed resolutions, refining each until a stable, justified outcome is reached.

Workflow Visualization

Conceptual Mapping of Ethical Theories

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and primary focus of each major ethical theory within a biomedical context.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Ethical Theories in Biomedical Contexts

| Feature | Utilitarianism | Deontology | Virtue Ethics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Outcome / Consequence [3] | Act / Duty [3] | Agent / Character [3] |

| Core Question | What action maximizes overall well-being? | What is my duty, regardless of outcome? | What would a virtuous person do? |

| Key Proponents | Bentham, Mill [3] | Kant [3] | Aristotle [3] |

| Central Concept | Greatest Happiness Principle [3] | Categorical Imperative [3] | Eudaimonia (Human Flourishing) [3] |

| Strengths in Biomedicine | Provides a clear calculus for public health policy; aims for objective, collective benefit [4]. | Robustly defends individual rights and autonomy; provides clear rules [4]. | Holistic; integrates motive, action, and outcome; emphasizes professional integrity [3]. |

| Weaknesses in Biomedicine | May justify harming minorities for majority benefit; can be impractical to calculate all consequences [4]. | Can be rigid; may ignore disastrous outcomes of "right" actions [3]. | Can be vague; virtues may be interpreted differently; lacks specific action-guidance [3]. |

| Biomedical Example | Rationing a scarce drug to save the most lives during a pandemic. | Obtaining informed consent from every research participant, without exception. | A researcher displaying compassion when withdrawing a patient from a trial. |

Modern research, particularly in the drug development and biopharmaceutical fields, operates at the intersection of scientific innovation and profound ethical responsibility. Navigating the complex challenges that arise requires a robust and systematic framework. This technical support center is designed to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals identify, analyze, and resolve these interdisciplinary ethical dilemmas by applying the four core principles of bioethics: Autonomy (respect for individuals' right to self-determination), Beneficence (the obligation to do good), Non-maleficence (the duty to avoid harm), and Justice (ensuring fairness and equity) [6]. By framing common operational challenges within this structure, we provide a practical methodology for upholding ethical standards in daily research practice.

Ethical Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Participant Recruitment and Informed Consent

This section addresses common ethical challenges in enrolling research participants and obtaining truly informed consent.

Problem: Inconsistent comprehension during the consent process.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Autonomy. A key component of informed consent is that the participant comprehends the disclosure [6].

- Root Cause: Complex scientific language, inadequate time for discussion, or cultural and health literacy barriers.

- Solution: Implement a multi-stage consent process. Provide consent documents well in advance, use teach-back methods to confirm understanding, and allow for a "cooling-off" period where participants can discuss with family or advisors. Ensure documents are translated and culturally adapted for the target population.

Problem: Selection bias leading to non-representative cohorts.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Justice. This principle demands a fair distribution of the benefits and burdens of research [6] [7].

- Root Cause: Over-reliance on convenient recruitment channels (e.g., single clinic sites) or overly restrictive eligibility criteria that are not scientifically justified.

- Solution: Utilize diverse recruitment strategies, including social media and community outreach, to reach underrepresented groups [7]. Employ randomization techniques to minimize selection bias and critically review eligibility criteria to ensure they are necessary [7].

Problem: Perceived therapeutic misconception.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Autonomy and Non-maleficence. Participants may incorrectly believe that the primary goal of the research is to provide them with therapeutic benefit, potentially leading to harm if they for proven treatments.

- Root Cause: Insufficient clarity in communication that distinguishes research from clinical care.

- Solution: Explicitly and repeatedly state the research nature of the intervention. Clearly explain the difference between diagnostic tests for clinical care and those for research data collection. Document these discussions within the consent form.

Guide 2: Data Integrity, Privacy, and Security

This guide focuses on ethical challenges related to the handling and protection of research data.

Problem: High background noise or non-specific binding in sensitive assays (e.g., ELISA).

- Ethical Principle Affected: Beneficence and Non-maleficence. Inaccurate data can lead to incorrect conclusions, potentially harming future patients who receive an unsafe or ineffective product [7].

- Root Cause: Contamination of kit reagents by concentrated sources of the analyte, improper washing techniques, or use of incompatible equipment [8].

- Solution: Strictly segregate pre- and post-sample analysis workspaces. Clean all surfaces and equipment before use, and employ pipette tips with aerosol filters. Use only the recommended wash buffers and techniques to avoid introducing artifacts [8].

Problem: Inappropriate data interpolation from non-linear assay results.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Beneficence and Non-maleficence. Using an incorrect curve-fitting model (e.g., linear regression for an inherently non-linear immunoassay) introduces inaccuracies, especially at the critical low and high ends of the standard curve [8].

- Root Cause: Reliance on R-squared values without validating the model's accuracy across the analytical range.

- Solution: Use robust curve-fitting routines like Point-to-Point, Cubic Spline, or 4-Parameter logistics. Validate the model by "back-fitting" the standards as unknowns; the model should report their nominal values accurately [8].

Problem: Risk of participant re-identification from shared data.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Autonomy (Confidentiality) and Non-maleficence. Breaching confidentiality violates the trust established in the informed consent process and could cause harm to the participant [6] [7].

- Root Cause: Data sharing without proper de-identification protocols or insufficient data security measures.

- Solution: Store personal identifiers and scientific data separately. Limit data access through role-based controls and establish data use agreements with all external partners. Implement strong cybersecurity measures for electronic data, especially with the rise of wearables and EHRs [7].

Guide 3: Risk-Benefit Analysis and Post-Trial Responsibilities

This section tackles challenges in evaluating risks and benefits and upholding responsibilities after a trial concludes.

Problem: Difficulty quantifying and communicating uncertain risks.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Autonomy and Non-maleficence. Participants cannot make an autonomous decision without a realistic understanding of potential risks.

- Root Cause: Inherent scientific uncertainties in early-phase research and the use of vague, non-quantitative language.

- Solution: Conduct a thorough risk-benefit assessment that considers the severity, frequency, and preventability of adverse reactions [7]. Communicate risks using clear, quantitative terms where possible (e.g., "this side effect was seen in approximately 1 in 10 patients at this dose level") and acknowledge uncertainties explicitly.

Problem: Ensuring continued access to beneficial treatment post-trial.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Justice and Beneficence. It is unjust if only participants in certain regions or from wealthy backgrounds can continue a life-saving treatment after the trial ends [7].

- Root Cause: Lack of pre-trial planning and funding for post-trial access, particularly in globalized trials.

- Solution: Address post-trial access plans during the study design and ethics review phase. Develop transparent policies for providing continued treatment, detailing eligibility and duration. Facilitate a seamless transition for participants back to the standard healthcare system [7].

Problem: Managing incidental findings.

- Ethical Principle Affected: Beneficence and Autonomy. Researchers have an obligation to act on potentially clinically significant findings discovered during research, but must also respect the participant's right not to know.

- Root Cause: Advances in diagnostic technologies that reveal information beyond the primary research objectives.

- Solution: Establish a clear protocol before the study begins. This should define what constitutes a reportable incidental finding, outline the process for clinical confirmation, and detail how participants will be offered the option to receive or decline such information during the consent process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can we apply the principle of autonomy in cultures with a family- or community-centered decision-making model? A1: Respecting autonomy does not necessarily mean imposing a Western individualistic model. The principle can be upheld through relational autonomy, which acknowledges that decisions are often made within a social context [6]. The consent process should involve engaging with the family or community leaders as the patient desires, while still ensuring that the individual participant's values and preferences are respected and that they provide their ultimate agreement [9].

Q2: What are the emerging ethical concerns with using AI and Machine Learning in drug development? A2: The primary concerns revolve around accountability, transparency, and bias [7]. While AI can automate tasks and save time, algorithmic decision-making without human oversight may perpetuate or amplify existing biases in training data, leading to unjust outcomes. There is also a risk of a "black box" effect where the rationale for a decision is unclear, challenging the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. Ensuring human-in-the-loop validation and auditing algorithms for bias are critical steps [7].

Q3: How can a values-based framework, like the TRIP & TIPP model, help in daily R&D decisions? A3: A structured model, such as the one using values (Transparency, Respect, Integrity, Patient Focus) and contextual factors (Timing, Intent, Proportionality, Perception), provides a practical, prospective decision-making tool [10]. It engages employees as moral agents by asking specific framing questions (e.g., "How does this solution put the patient's interests first?" or "Is the solution proportional to the situation?") to assess options against the organization's core values before a decision is finalized, reducing the need for top-down rules [10].

Q4: How does the principle of justice apply to environmental sustainability in pharmaceutical research? A4: Environmental ethics is an increasingly important aspect of justice. It involves the responsible use of resources and minimizing the environmental impact of drug manufacturing [7]. This aligns with global justice, as pollution and climate change disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. Furthermore, justice requires ensuring equitable distribution of treatments for global health emergencies, rather than focusing only on profitable markets [7].

Quantitative Data in Ethical Research

The following table summarizes key quantitative considerations for ensuring ethical compliance in clinical trials, directly supporting the principles of justice and beneficence.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Benchmarks for Ethical Clinical Trial Management

| Aspect | Quantitative Benchmark | Ethical Principle & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent Comprehension | > 80% score on a comprehension questionnaire post-consent discussion. | Autonomy: Ensures participants have adequate understanding to exercise self-determination. |

| Participant Diversity | Recruitment goals should aim to reflect the demographic prevalence of the disease, including racial, ethnic, and gender diversity. | Justice: Ensures fair burden and benefit sharing; data on drug efficacy and safety are representative. |

| Data Quality Control | Spike-and-recovery experiments for sample diluents should yield recoveries of 95% to 105% [8]. | Beneficence/Non-maleficence: Ensures data integrity, which is foundational to making correct conclusions about safety and efficacy. |

| Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) Review | Interim safety reviews triggered by pre-defined thresholds (e.g., specific serious adverse event rates). | Non-maleficence: Protects current participants from undue harm by allowing for early trial termination if risks outweigh benefits. |

| Post-Trial Access Transition | Plan for seamless transition, with a defined timeframe (e.g., supply of investigational product for 30-60 days post-trial). | Justice/Beneficence: Prevents abrupt cessation of care for participants who benefited from the investigational product. |

Experimental Protocol: An Ethics-Based Risk Assessment

This protocol provides a methodology for prospectively evaluating a research study's ethical soundness.

Objective: To systematically identify, assess, and mitigate ethical risks in a research protocol before implementation.

Materials: Research protocol document, multidisciplinary team (e.g., clinical researcher, bioethicist, patient representative, data manager).

Methodology:

- Stakeholder Mapping: Identify all stakeholders (e.g., participants, researchers, sponsors, the community) and how the research impacts them.

- Principle-by-Principle Review:

- Autonomy: Walk through the informed consent process. Is the language accessible? Is there a plan to assess comprehension? How are cultural preferences for decision-making incorporated?

- Beneficence/Non-maleficence: List all potential benefits and harms (physical, psychological, social, economic). Quantify their likelihood and severity. Justify that the potential benefits outweigh the risks.

- Justice: Scrutinize the participant selection criteria. Is the population inclusive of those who will use the drug? Are there groups being excluded without scientific justification?

- Contextual Factor Analysis (TIPP): Evaluate the proposal using the TIPP framework [10]:

- Timing: Is this the right time for this research, considering public health needs and available standard of care?

- Intent: Is the primary aim scientific communication and patient benefit, or are there conflicting commercial or promotional intentions?

- Proportionality: Is the scale of the research (number of participants, resources) proportionate to the question it seeks to answer?

- Perception: How would the research plan be perceived by the public or a skeptical audience? Is it transparent and trustworthy?

- Mitigation Planning: For each identified ethical risk, develop a specific mitigation strategy (e.g., enhanced consent process, revised eligibility criteria, a DMC charter).

Visualizing the Ethical Decision-Making Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the structured, five-step process for applying ethical principles to resolve complex research dilemmas, integrating company values and contextual factors [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Their Ethical Significance

| Item | Function | Ethical Principle Connection |

|---|---|---|

| Validated & De-identified Biobank Samples | Provides biological specimens for research while protecting donor identity. | Autonomy/Respect: Requires proper informed consent for storage and future use. Justice: Promotes equitable resource sharing. |

| Accessible Data Visualization Tools | Software with built-in, colorblind-friendly palettes (e.g., Viridis, Cividis) and perceptually uniform color gradients [11] [12]. | Justice: Ensures scientific information is accessible to all colleagues and the public, regardless of visual ability. Prevents exclusion and misinterpretation. |

| Role-Based Electronic Data Capture (EDC) System | Securely collects and manages clinical trial data with tiered access levels. | Confidentiality (Autonomy): Protects participant privacy. Integrity: Ensures data accuracy and traceability, supporting beneficence and non-maleficence. |

| Contamination-Free Assay Reagents | Highly sensitive ELISA kits and related reagents for accurate impurity detection [8]. | Beneficence/Non-maleficence: Accurate data is fundamental to ensuring product safety and efficacy. Preventing contamination is a technical and ethical imperative. |

| Multilingual Consent Form Templates | Standardized consent documents that can be culturally and linguistically adapted. | Autonomy: Empowers participants by providing information in their native language, facilitating true understanding and voluntary agreement. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our predictive model for patient health risks performs well overall but shows significantly lower accuracy for our minority patient populations. What are the first steps we should take to investigate this?

A1: This pattern suggests potential data bias. Begin your investigation by auditing your training data for representation disparities and label quality across different demographic groups [13]. You should also analyze the model's feature selection process to determine if it is disproportionately relying on proxies for sensitive attributes [14]. Technically, you can employ adversarial de-biasing during training, which involves jointly training your predictor and an adversary that tries to predict the sensitive attribute (e.g., race) from the model's representations. If the adversary fails, it indicates the representation does not encode bias [15].

Q2: We are developing an early warning system for use in a clinical nursing setting. What are the primary ethical risks we should address in our design phase?

A2: The key ethical risks can be categorized into five dimensions [16]:

- Data- and Algorithm-Related Risks: Including data privacy breaches and algorithmic unfairness.

- Professional Role Risks: Ambiguity in responsibility attribution when algorithm-driven decisions lead to errors.

- Patient Rights Risks: Potential dehumanization of care and threats to patient autonomy.

- Governance Risks: Lack of transparency and potential for misuse of the system.

- Accessibility Risks: Barriers to the technology's adoption and social acceptance.

Q3: A fairness audit has revealed that our algorithm exhibits bias. What are some algorithmic techniques we can use to mitigate this bias without scrapping our entire model?

A3: Several technical approaches can be implemented [15]:

- Adversarial De-biasing: As described above, this technique protects sensitive attributes by making it impossible for an adversary to predict them from the model's internal representations.

- Variational Fair Autoencoders (VFAE): This is a semi-supervised method that learns an invariant representation of the data by explicitly separating sensitive attributes (

s) from other latent variables (z). It uses a Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) penalty to ensure the distributions ofzare similar across different groups of the sensitive attribute. - Dynamic Upsampling: This technique involves intelligently upsampling underrepresented groups in the training data based on learned latent representations.

- Distributionally Robust Optimization: This method prevents disparity amplification by optimizing the model for worst-case subgroup performance.

Q4: Our interdisciplinary team, comprising computer scientists, bioethicists, and clinicians, often struggles with aligning on a definition of "fairness." How can we navigate this challenge?

A4: This is a core interdisciplinary challenge. Facilitate a series of workshops to explicitly define and document the operational definition of fairness for your specific project context. You should map technical definitions (e.g., demographic parity, equalized odds) to clinical and ethical outcomes. Furthermore, establish a continuous monitoring framework to assess the chosen fairness metric's real-world impact, acknowledging that definitions may need to evolve [16] [14].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue | Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Disparity | Model accuracy/recall is significantly lower for a specific demographic subgroup [14]. | Non-representative Training Data, Feature Selection Bias, or Temporal Bias where disease patterns have changed [13]. | 1. Audit and rebalance training datasets.2. Apply algorithmic fairness techniques like adversarial de-biasing [15].3. Implement continuous monitoring and model retraining protocols. |

| Feedback Loop | The model's predictions over time reinforce existing biases and reduce accuracy [14]. | Development Bias where the model is trained on data reflecting past human biases, creating a self-reinforcing cycle. | Design feedback mechanisms that collect ground truth data independent of the model's predictions. Regularly audit model outcomes for reinforcing patterns. |

| "Black Box" Distrust | Clinical end-users (e.g., nurses) do not trust the model's recommendations and override them [16]. | Lack of Transparency and Explainability, leading to a conflict with professional autonomy. | Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) techniques to provide rationale for predictions. Involve end-users in the design process and provide digital literacy training [16]. |

| Responsibility Gaps | Uncertainty arises when the model makes an erroneous recommendation; it is unclear who is accountable [16]. | Unclear Governance and Accountability frameworks for shared human-AI decision-making. | Develop clear organizational policies that delineate responsibility between developers, clinicians, and institutions. Establish an ethical review board [16]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Algorithmic Bias

Table 1: Categorization and Prevalence of Bias in Medical AI

| Bias Category | Source / Sub-type | Description | Example in a Medical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Bias | Historical Data Bias | Training data reflects existing societal or health inequities [14]. | An algorithm trained on healthcare expenditure data unfairly allocates care resources because it fails to account for different access patterns among racial groups [14]. |

| Reporting Bias | Certain events or outcomes are reported at different rates across groups. | Under-reporting of symptoms in a specific demographic leads to a model that is less accurate for that group. | |

| Development Bias | Algorithmic Bias | The model's objective function or learning process inadvertently introduces unfairness [13]. | A model optimized for overall accuracy may sacrifice performance on minority subgroups. |

| Feature Selection Bias | Chosen input variables act as proxies for sensitive attributes [13]. | Using "postal code" as a feature, which is highly correlated with race and socioeconomic status. | |

| Interaction Bias | Temporal Bias | Changes in clinical practice, technology, or disease patterns over time render the model obsolete or biased [13]. | A model trained pre-pandemic may be ineffective for post-pandemic patient care. |

| Feedback Loop | Model predictions influence future data collection, reinforcing initial biases [14]. | A predictive policing algorithm leads to over-policing in certain neighborhoods, generating more arrest data that further biases the model [14]. |

Table 2: Governance Pathways for Ethical AI in Healthcare

| Governance Pathway | Concrete Measures | Key Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Technical–Data Governance [16] | Privacy-preserving techniques (e.g., federated learning), bias monitoring dashboards, fairness audits. | To ensure data security and algorithmic fairness through technical safeguards. |

| Clinical Human–Machine Collaboration [16] | Nurse and clinician training in AI literacy, designing transparent interfaces, interdisciplinary co-creation teams. | To foster trust and effective collaboration between healthcare professionals and AI systems. |

| Organizational-Capacity Building [16] | Establishing AI ethics review boards, creating clear accountability frameworks, investing in continuous staff training. | To build institutional structures that support the ethical deployment and use of AI. |

| Institutional–Policy Regulation [16] | Developing and enforcing clinical guidelines for AI use, promoting standardised reporting of model performance and fairness. | To create a regulatory environment that ensures safety, efficacy, and equity. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Adversarial De-biasing for Fair Representation Learning

Objective: To train a predictive model that learns a representation of the input data which is maximally informative for the target task (e.g., predicting patient risk) while being minimally informative about a protected sensitive attribute (e.g., race or gender).

Methodology:

- Model Architecture: Construct a multi-head neural network.

- A shared encoder network,

g(X), that learns a representation of the input data. - A predictor head,

f(g(X)), which is trained to minimize the prediction loss for the target labelY. - An adversary head,

a(g(X)), which is trained to minimize the prediction loss for the sensitive attributeZfrom the shared representationg(X).

- A shared encoder network,

- Training Procedure: The overall optimization is a minimax game with the following objective [15]:

- Minimize the predictor's loss

L_y(f(g(X)), Y). - Maximize (or minimize the negative of) the adversary's loss

L_z(a(g(X)), Z). - This is achieved by using a gradient reversal layer (

J_λ) between the shared encoder and the adversary. During backpropagation, this layer passes gradients to the encoder with a negative factor (-λ), encouraging the encoder to learn features that confuse the adversary.

- Minimize the predictor's loss

- Hyperparameters: The trade-off between prediction accuracy and fairness is controlled by the hyperparameter

λ.

Protocol 2: Bias Audit using Variational Fair Autoencoder (VFAE)

Objective: To learn a latent representation of the data that is invariant to a specified sensitive attribute, and to use this representation for downstream prediction tasks to reduce bias.

Methodology:

- Architecture: Employ a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) framework with a specific structure designed for fairness.

- The model assumes a data generation process where an input

xis generated from a sensitive variablesand a latent variablez1that encodes the remaining, non-sensitive information. - To prevent

z1from becoming degenerate, a second latent variablez2is introduced to capture noise not explained by the labely.

- The model assumes a data generation process where an input

- Loss Function: The model is trained by maximizing a penalized variational lower bound. The key component for fairness is the Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) penalty, which is added to the standard VAE loss [15].

- MMD Penalty: This term explicitly encourages the distributions of the latent representation

z1to be similar across different values of the sensitive attributes(e.g.,q_φ(z1|s=0)andq_φ(z1|s=1)). It measures the distance between the mean embeddings of these two distributions in a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS). - Semi-supervised Application: This architecture can naturally handle both labelled and unlabelled data, making it suitable for real-world clinical settings where labels may be scarce.

Visualizations

Adversarial De-biasing Workflow

VFAE Architecture for Invariant Representations

Five Ethical Risks and Four Governance Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|

| Adversarial De-biasing Framework | A neural network architecture designed to remove dependence on sensitive attributes by using a gradient reversal layer to "confuse" an adversary network [15]. |

| Variational Fair Autoencoder (VFAE) | A semi-supervised generative model that learns an invariant data representation by leveraging a Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) penalty to ensure latent distributions are similar across sensitive groups [15]. |

| AI Fairness 360 (AIF360) Toolkit | An open-source library containing a comprehensive set of metrics for measuring dataset and model bias, and algorithms for mitigating bias throughout the ML pipeline. |

| Fairness Auditing Dashboard | A custom software tool for continuously monitoring model performance and fairness metrics (e.g., demographic parity, equalized odds) across different subgroups in a production environment [16]. |

| Interdisciplinary Review Board (IRB) | A governance structure, not a technical tool, but essential for evaluating the ethical implications of AI systems. It should include bioethicists, clinicians, data scientists, and legal experts [16]. |

Welcome to the Interdisciplinary Support Center

This support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals overcome common interdisciplinary communication challenges in bioethics methodology research. The resources below address specific issues that arise when translating technical jargon across domains.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why do my protocol descriptions frequently get misinterpreted when shared with ethics review boards?

A: This is a common interdisciplinary challenge. Ethics board members may lack the specific technical context you possess. To mitigate this:

- Pre-define all acronyms and technical terms in a shared glossary at the beginning of your document.

- Use analogies that relate complex biological processes to more familiar concepts.

- Structure your methodology using visual workflows (see diagrams below) to make the process flow logically clear, even to non-specialists.

Q: How can I ensure the ethical implications of my technical work are accurately understood by a diverse research team?

A: Foster a shared conceptual framework.

- Develop cross-disciplinary lexicons: Create a living document of key terms with definitions from both technical and ethical perspectives.

- Implement structured communication protocols: Hold kickoff meetings where each discipline explains their core concepts and potential ethical red flags to the others.

- Use scenario-based planning: Walk through the experimental protocol step-by-step as a group to identify and discuss potential ethical decision points.

Q: What is the most effective way to present quantitative data on drug efficacy to an audience that includes bioethicists, scientists, and regulators?

A: Clarity and context are paramount. Present data in clearly structured tables that allow for easy comparison. Always pair quantitative results with a qualitative interpretation that explains the significance of the data from both a scientific and an ethical standpoint. Avoid presenting data without this crucial narrative framing.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Workflow Gaps

Problem: Critical communication breakdowns occur at handoff points between molecular biology teams and clinical research teams.

Solution: Implement the standardized Interdisciplinary Experimental Workflow.

Interdisciplinary Research Workflow

Problem: A key ethical consideration is overlooked in the early stages of experimental design, causing delays and protocol revisions later.

Solution: Utilize the Ethical Risk Assessment Pathway to embed ethics throughout the research lifecycle.

Ethical Risk Assessment Pathway

Data Presentation Standards

| Metric | Molecular Biology Data | Clinical Application Data | Bioethics Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Efficacy Rate | 95% Target Protein Inhibition | 70% Patient Response Rate | Informs risk/benefit analysis for vulnerable populations. |

| Adverse Event Incidence | 5% High-grade in model | 2% Occurrence in Phase II trial | Critical for informed consent documentation clarity. |

| Statistical Significance (p-value) | p < 0.001 | p < 0.01 | Determines threshold for claiming effectiveness versus overstating results. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Disciplinary Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Interdisciplinary Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing System | Precise genomic modification for creating disease models. | Raises ethical questions on genetic alteration boundaries; requires clear explanation for non-specialists. |

| Primary Human Cell Lines | Provides a more physiologically relevant experimental model. | Sourcing and informed consent documentation are paramount for ethics review; provenance must be unambiguous. |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Kits | Amplifies specific DNA sequences for detection and analysis. | Technical "cycle threshold" values must be translated into clinical detectability/likelihood concepts. |

| Informed Consent Form Templates | Legal and ethical requirement for human subjects research. | Language must be translated from legalese into technically accurate yet comprehensible layperson's terms. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Cross-Disciplinary Comprehension

Objective

To quantitatively and qualitatively measure the effectiveness of jargon-translation strategies in conveying a complex experimental methodology to an interdisciplinary audience.

Methodology

- Participant Recruitment: Form three groups: (1) technical specialists, (2) bioethicists, and (3) drug development professionals.

- Material Preparation: Develop two versions of a complex experimental protocol:

- Version A: Uses standard, domain-specific technical language.

- Version B: Incorporates a glossary, visual aids (see workflows above), and translated jargon.

- Procedure: Randomly assign participants to review either Version A or Version B. Following review, all participants complete a standardized assessment measuring:

- Accuracy: Comprehension of the protocol's core steps and objectives.

- Efficiency: Time taken to complete the assessment.

- Perceived Clarity: Self-reported rating of the material's understandability.

- Data Analysis: Compare assessment scores, completion times, and clarity ratings between groups and between the two protocol versions using statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA).

Expected Outcome

It is hypothesized that Version B of the protocol will yield significantly higher comprehension accuracy, faster reading times, and higher perceived clarity across all three professional groups, demonstrating the efficacy of structured communication tools in bridging interdisciplinary gaps.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Integrated Ethical Methodologies

Introducing the Embedded Ethics and Social Science Approach

Core Concepts and Workflow

The Embedded Ethics and Social Science (EESS) approach integrates ethicists and social scientists directly into technology development teams. This interdisciplinary collaboration proactively identifies and addresses ethical and social concerns throughout the research lifecycle, moving beyond after-the-fact analysis to foster responsible, inclusive, and ethically-aware technology innovation in healthcare and beyond [17].

Key Characteristics of the EESS Approach

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Integration | Ethics and social science researchers are embedded within the project team, participating in regular meetings and day-to-day work [17]. |

| Interdisciplinarity | Fosters collaboration between ethicists, social scientists, AI researchers, and domain specialists (e.g., clinicians) from the project's outset [17]. |

| Proactivity | Aims to anticipate ethical and social concerns before they manifest as real-world harm, shaping responsible technology innovation [17]. |

| Contextual Sensitivity | Develops a profound understanding of the project's specific technological details and application context [17]. |

Implementation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the continuous and iterative workflow for implementing the Embedded Ethics approach:

The Researcher's Toolkit: EESS Methodologies

The EESS approach employs a toolbox of empirical and normative methods. The table below details these key methodologies and their primary functions in the research process.

Methodological Toolbox

| Method | Primary Function in EESS |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder Analyses [17] | Identifies all relevant parties affected by the technology to understand the full spectrum of impacts and values. |

| Literature Reviews [17] | Establishes a foundation in existing ethical debates and empirical social science research relevant to the project. |

| Ethnographic Approaches [17] | Provides deep, contextual understanding of the practices and cultures within the development and deployment environments. |

| Peer-to-Peer Interviews [17] | Elicits insider perspectives and unarticulated assumptions within the interdisciplinary project team. |

| Focus Groups [17] | Generates data on collective views and normative stances regarding the technology and its implications. |

| Bias Analyses [17] | Systematically examines datasets and algorithms for potential discriminatory biases or unfair outcomes. |

| Workshops [17] | Facilitates collaborative problem-solving and interdisciplinary inquiry into identified ethical concerns. |

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Challenges

Problem 1: Lack of Team Engagement

The Challenge: The embedded ethics team is not adequately involved in core project meetings or strategic discussions, limiting their understanding and impact.

The Solution:

- Secure leadership buy-in from the outset to mandate participation in regular team meetings [18].

- Clarify roles and responsibilities for all team members, including embedded ethicists, within the project protocol [19].

- Foster a collaborative culture by having the embedded researcher spend time in the team's environment and participate in day-to-day work on a social level [17].

Problem 2: Identifying Relevant Ethical Issues

The Challenge: The project team struggles to anticipate potential ethical and social concerns during the planning and early development stages.

The Solution:

- Conduct a structured ethical walkthrough at the project's start. Use key questions to scope potential issues [18]:

- Perform an initial stakeholder analysis to map all parties affected by the technology and anticipate issues of justice and fairness [17].

Problem 3: Managing Interdisciplinary Communication

The Challenge: Communication barriers between ethicists, social scientists, and technical staff hinder effective collaboration.

The Solution:

- Establish a shared vocabulary and encourage team members to clarify technical details and ethical concepts during meetings [17].

- Use iterative feedback loops. Present initial ethical analyses and refine them based on technical feedback, moving between established debates and specific development problems [17].

- Employ visual aids, such as workflow diagrams, to make complex ethical considerations and project relationships accessible to all disciplines [19].

Problem 4: Integrating Ethics into Technical Workflows

The Challenge: Ethical reflections remain theoretical and are not translated into practical changes in the technology's design or deployment.

The Solution:

- Focus on "bias analyses" as a concrete method to collaborate with technical teams on a well-defined problem, leading to tangible improvements in algorithms or datasets [17].

- Develop a publication policy early on that clarifies how results will be disseminated, which can serve as a concrete framework for discussing responsible communication [19].

- Co-design solutions. The embedded ethicist should not only identify problems but also work directly with developers to advise on and help design ethically-informed technical solutions [17].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

In the context of EESS, "research reagents" are the conceptual tools and frameworks used to conduct the analysis. The table below lists essential items for this methodological approach.

EESS Research Reagents

| Item / Framework | Function in EESS |

|---|---|

| Research Protocol [19] | The master document outlining the project's rationale, objectives, methodology, and ethical considerations. Serves as a common reference. |

| Informed Consent Forms [19] | Ensures that research participants, and potentially other stakeholders, are provided with the information they need to make an autonomous decision. |

| Data Management Plan [19] | Details how research data (both technical and qualitative) will be handled, stored, and analyzed, ensuring integrity and compliance. |

| Stakeholder Map [17] | A visual tool that identifies all individuals, groups, and organizations affected by the technology, used to guide engagement and analysis. |

| Interview & Focus Group Guides [17] | Semi-structured protocols used to collect qualitative data from various stakeholders, ensuring methodological standardization. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This support center provides resources for researchers and scientists to navigate technical and ethical challenges in bioethics methodology research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core function of an "Embedded Ethicist" in a research project? The Embedded Ethicist is not an external auditor but a integrated team member who facilitates ethical reflection throughout the research lifecycle. They move ethics beyond a compliance checklist ("research ethics") to become a substantive research strand ("ethical research") that scrutinizes the moral judgments, values, and potential conflicts inherent in the project's goals and methodologies [20].

Q2: How can I structure a troubleshooting process to be both efficient and thorough? Adopt a logical "repair funnel" approach. Start with the broadest potential causes and systematically narrow down to the root cause [21]. Key areas to isolate initially are:

- Method-related issues: Verify all parameters and procedures.

- Mechanical-related issues: Inspect instrumentation and hardware.

- Operation-related issues: Review human factors and execution.

Q3: Why is it critical to change only one variable at a time during experimental troubleshooting? Changing multiple variables simultaneously causes confusion and delays by making it impossible to determine which change resolved the issue. Always isolate variables and test them one at a time to correctly identify the root cause [22].

Q4: How can our team proactively identify ethical blind spots in our technology development? Utilize structured approaches like the Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (ELSI) framework. This involves integrating ethical analysis right from the project's beginning, rather than as an after-the-fact evaluation. This can include ethics monitoring throughout the project cycle and formulating specific ethical research questions about the underlying values of the technology being developed [20].

Q5: What is the most important feature for a digital help center or knowledge base? Robust search functionality. A prominent, AI-powered search bar is essential for users to find answers quickly. An intuitive search reduces frustration and empowers users to resolve issues independently, which is a core goal of self-service [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Experimental Protocol Failures

This guide outlines a systematic protocol for diagnosing failed experiments.

Required Materials:

| Research Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Positive Control Samples | Verifies the protocol is functioning correctly by using a known positive outcome. |

| Negative Control Samples | Confirms the absence of false positives and validates the assay's specificity. |

| Fresh Reagent Batches | Isolates reagent degradation as a failure source. |

| Lab Notebook | Documents all steps, observations, and deviations for traceability. |

| Equipment Service Records | Provides historical performance data for instrumentation. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Repeat the Experiment: Unless cost or time-prohibitive, repeat the experiment to rule out simple human error [22].

- Validate the Result: Critically assess if the unexpected result constitutes a failure. Revisit the scientific literature—could the result be biologically plausible? A dim signal, for instance, might indicate a protocol problem or low protein expression [22].

- Verify Controls: Ensure you have included appropriate positive and negative controls. A valid positive control helps determine if the problem lies with the protocol itself [22].

- Inspect Equipment & Reagents: Check for improper storage or expired reagents. Visually inspect solutions for cloudiness or precipitation. Confirm compatibility of all components (e.g., primary and secondary antibodies) [22].

- Change Variables Systematically: Generate a list of potential failure points (e.g., concentration, incubation time, temperature). Change only one variable at a time, starting with the easiest to test [22].

- Document Everything: Meticulously record every step, variable changed, and the corresponding outcome in your lab notebook. This creates a valuable reference for your team [21] [22].

The workflow below visualizes this structured troubleshooting process:

Guide 2: Resolving Instrument Performance Issues

Apply the "repair funnel" logic to narrow down instrument problems.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Gather Preliminary Information: Ask: What was the last action before the issue? How frequent is the problem? Check the instrument logbook and software error logs. Establish what "normal" looks like from historical data [21].

- Reproduce the Issue: Can you modify parameters to reliably reproduce the problem? Consistent reproduction is key to understanding the root cause [21].

- Isolate the System:

- Confirm Parameters: Meticulously verify that all method parameters match the intended protocol. Software updates or accidental saves can alter locked-down methods [21].

- Use "Half-Splitting": For modular instruments, isolate whether the problem lies in one major subsystem (e.g., the chromatography side vs. the mass spec side) to focus repair efforts [21].

- Perform the Repair:

- Document and Propose Prevention: Before concluding, fully document the issue and resolution. Include any service records. Propose adjustments to preventative maintenance schedules to avoid recurrence [21].

The following diagram illustrates the isolation and diagnosis process:

Key Performance Indicators for Research Support

Track the following metrics to measure the efficiency of your support structures, whether for technical or ethical guidance [23] [25].

| Support Metric | Definition | Target Goal |

|---|---|---|

| First Contact Resolution | Percentage of issues resolved in the first interaction. | > 70% |

| Average Resolution Time | Mean time taken to fully resolve a reported issue. | Minimize Trend |

| Self-Service Usage Rate | Percentage of users who find answers via knowledge base/FAQs without submitting a ticket. | Increase Trend |

| Customer Satisfaction (CSAT) | User satisfaction score with the support received. | > 90% |

| Ticket Deflection Rate | Percentage of potential tickets prevented by self-service resources. | Increase Trend |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Interdisciplinary Methodology Challenges

This guide addresses frequent methodological problems encountered in interdisciplinary bioethics research, providing practical solutions to ensure rigor and credibility.

1. Problem: How to resolve conflicting conclusions from different disciplinary methods. A philosopher and a sociologist on the same team reach different normative conclusions from the same data.

- Solution: Implement a structured deliberation framework.

- Action: Facilitate a meeting where each researcher explicitly states their research question, methodological approach, key assumptions, and standards of evidence.

- Goal: To map the points of divergence and identify if the conflict is factual (disagreement on data), methodological (disagreement on how to interpret), or foundational (disagreement on core values) [1].

- Outcome: Foster mutual understanding and work towards an integrated conclusion that acknowledges the strengths and limitations of each perspective.

2. Problem: How to establish legitimacy and authority for interdisciplinary bioethics research. Research is criticized for lacking rigor because it doesn't conform to the standards of a single, traditional discipline [1].

- Solution: Proactively define and justify the research framework.

- Action: In publications and proposals, clearly articulate the chosen interdisciplinary model (multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary), the rationale for the selected methods, and the integrated standard of rigor being applied [1].

- Goal: To preempt criticism by demonstrating a self-aware and systematic approach to interdisciplinary work.

- Outcome: Enhance the research's credibility with funders, journals, and peers.

3. Problem: How to conduct a bias audit on a dataset or algorithm. A machine learning model, used to classify historical archival images, is found to perpetuate historical under-representation of certain social groups [26].

- Solution: Implement a multi-stage bias mitigation protocol.

- Action:

- Interdisciplinary Scrutiny: Assemble a team with domain experts (e.g., historians, ethicists) and technical experts (data scientists) to review the data and model outputs [26].

- Technical Interrogation: Use techniques like data augmentation (e.g., balancing dataset representation) and adversarial debiasing to reduce algorithmic unfairness [26].

- Continuous Monitoring: Establish a plan for ongoing auditing and refinement of the model after deployment [26].

- Goal: To identify and mitigate bias at multiple stages, from data selection and annotation to algorithmic design [26].

- Outcome: Develop a more fair, accurate, and ethically sound model.

- Action:

4. Problem: How to integrate diverse stakeholder values into ethical analysis. A clinical ethics consultation struggles to balance the perspectives of hospital administrators, clinicians, patients, and family members.

- Solution: Employ structured stakeholder analysis and ethnographic methods.

- Action:

- Stakeholder Mapping: Identify all relevant parties and their respective interests, influence, and ethical stakes.

- Ethnographic Engagement: Use methods like targeted interviews and direct observation to understand the lived experiences, values, and decision-making processes of these stakeholder groups.

- Goal: To ensure all relevant voices are identified and their values are genuinely understood, not just assumed.

- Outcome: A more robust, inclusive, and practical ethical analysis that is grounded in the real-world context.

- Action:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What constitutes rigor in interdisciplinary bioethics research? Rigor is not about adhering to the standards of a single discipline but about the justified and transparent application of multiple methods to a research question. This involves clearly explaining the choice of methods, how they are integrated, and the criteria used to evaluate the validity of the resulting conclusions [1].

Q2: What are the core challenges of interdisciplinary work in bioethics? Key challenges include: the lack of clear, unified standards for answering bioethical questions; difficulties in the peer-review process due to disciplinary differences; undermined credibility and authority; challenges in practical clinical decision-making; and questions about the field's proper institutional setting [1].

Q3: Why is a bias audit important in bioethics research? Bias audits are crucial because bioethical decisions often rely on data and algorithms that can inherit and amplify existing societal prejudices. Mitigating bias ensures more inclusive, accurate, and ethically sound outcomes, which is a core objective of bioethics [26].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Standards for Text Contrast in Accessible Visual Design This table outlines the minimum contrast ratios required by the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) for Level AAA, which helps ensure diagrams and text are readable for a wider audience, including those with low vision or color deficiencies [27] [28].

| Text Type | Definition | Minimum Contrast Ratio | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Text | Text that is at least 18.66px or 14pt in size, or bold text at least 14px or 10.5pt in size [29]. | 4.5:1 | A large, bolded heading. |

| Standard Text | Text that is smaller than 18.66px and not bold. | 7:1 | The main body text of a paragraph. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Methodological Rigor

| Item | Function in the Research Process |

|---|---|

| Structured Deliberation Framework | A protocol for facilitating discussion between disciplines to map conflicts and work towards integrated conclusions [1]. |

| Stakeholder Mapping Tool | A systematic process for identifying all relevant parties, their interests, and their influence in an ethical issue. |

| Bias Mitigation Techniques | Technical methods (e.g., data augmentation, adversarial debiasing) used to identify and reduce unfair bias in datasets and algorithms [26]. |

| Ethnographic Interview Guide | A semi-structured set of questions used to understand the lived experiences and values of stakeholders in a real-world context. |

Methodological Workflow Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the core process for conducting rigorous, interdisciplinary research in bioethics, integrating the tools discussed in this guide.

Interdisciplinary Research Workflow

This diagram details the specific steps involved in the critical "Bias Audit" phase of the research workflow.

Bias Audit Process

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the core types of research collaboration, and how do they differ?

Research collaboration exists on a spectrum of integration [30]:

| Collaboration Type | Definition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Unidisciplinary | An investigator uses models and methods from a single discipline [30]. | Traditional approach; single perspective. |

| Multidisciplinary | Investigators from different disciplines work on a common problem, but from their own disciplinary perspectives [30]. | Additive approach; work is done in parallel. |

| Interdisciplinary | Investigators from different disciplines develop a shared mental model and blend methods to address a problem in a new way [30]. | Integrative approach; interdependent work. |

| Transdisciplinary | An interdisciplinary collaboration that evolves into a new, hybrid discipline (e.g., neuroscience, bioengineering) [30]. | Creates a new field of study. |

FAQ 2: What are the common phases of an interdisciplinary science team?

Interdisciplinary teams typically progress through four key phases, each with distinct tasks [30]:

- Development: Team assembly, problem definition, and establishing a shared mental model and team identity [30].

- Conceptualization: Defining specific research questions, design, communication practices, and team roles [30].

- Implementation: Executing and coordinating the research plan, managing conflict, and integrating findings [30].

- Translation: Applying the team's knowledge to address the real-world problem, which may include forming partnerships with industry, government, or the public [30].

FAQ 3: What methodological challenges does interdisciplinary bioethics research face?

Bioethics draws on diverse disciplines, each with its own standards of rigor, leading to several challenges [1]:

| Challenge Area | Specific Issue |

|---|---|

| Theoretical Standards | No clear, agreed-upon standards for assessing normative conclusions from different disciplinary perspectives [1]. |

| Peer Review | Difficulty in interpreting criteria like "originality" and "validity" across disciplines, and a lack of awareness of other disciplines' methods [1]. |

| Credibility & Authority | The absence of a unified standard can undermine the perceived legitimacy of the research and researchers [1]. |

| Practical Decision-Making | In clinical settings, effectively integrating diverse disciplinary perspectives for ethical decision-making remains difficult [1]. |

FAQ 4: How can our team effectively manage social interactions and knowledge integration?

Successful teamwork requires managing social transactions to foster knowledge integration [30]. Key practices include:

- Schedule Time for Team Development: Dedicate time to build a shared vision, common goals, and direct communication about the science [30].

- Discuss Credit Early: Have explicit conversations about how recognition and credit will be shared among collaborators [30].

- Build Trust and Psychological Safety: Cultivate an environment of trust, which enables team members to blend their competencies openly [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Experiments or collaborative processes are yielding unexpected or inconsistent results.

This is a common issue in both wet-lab experiments and the "social experiments" of collaboration. A systematic approach to troubleshooting is essential [31] [32].

- Step 1: Define the Problem. Clearly articulate what was expected versus what occurred. For collaborative issues, identify the specific friction point (e.g., "ethicists and scientists disagree on risk assessment criteria") [32].

- Step 2: Analyze the Design. Scrutinize the experimental or team protocol [32]. Key elements to assess are shown in the table below:

| Element to Assess | Key Questions |

|---|---|

| Controls | Were appropriate controls in place? In collaboration, are there agreed-upon guidelines or moderators? [32] |

| Sample & Representation | Was the sample size sufficient? Does the team include all necessary disciplinary and stakeholder perspectives? [32] |

| Methodology & Communication | Was the methodology valid? Are team communication structures and practices effective? [30] |

| "Randomization" & Bias | Were subjects assigned randomly to minimize bias? Have team roles been assigned fairly to avoid disciplinary dominance? [32] |

- Step 3: Identify External Variables. Consider factors outside the immediate design that could be causing the failure, such as environmental conditions, timing, or unaccounted-for stakeholder interests [32].

- Step 4: Implement Changes. Modify the design based on your analysis. This could involve generating detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for experiments or re-establishing team communication practices [32].

- Step 5: Test the Revised Design. Retest the experiment or implement the new collaborative process to validate that the changes have addressed the issues [32].

Problem 2: The team is struggling to integrate knowledge from different disciplines.

This often stems from a lack of a shared mental model [30].

- Action: Facilitate a dedicated session where each discipline explains their core models, methods, and standards of "rigor" using accessible language [1]. Use a facilitator to help the group develop a shared framework for the specific project, acknowledging that a single standard of rigor may need to be negotiated [1].

Problem 3: Disagreements arise over post-trial responsibilities in high-risk clinical research.

This is a complex, real-world bioethical challenge where interdisciplinary input is critical [33].

- Action: Proactively assemble a broad range of stakeholders, including lab researchers, bioethicists, clinicians, participants, insurance experts, and policy makers, to discuss post-trial support before the trial begins [33]. Focus on defining the specific attributes of the irreversible treatment and the corresponding obligations, moving beyond theoretical debates to practical planning [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Interdisciplinary Collaboration

| Tool / Concept | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Shared Mental Model | A unified understanding of the research problem and approach that bridges disciplinary jargon and perspectives, enabling true integration [30]. |

| Field Guide for Collaboration | A living document that outlines the team's shared vision, goals, communication plans, and agreements on credit and authorship [30]. |

| Stakeholder Mapping | A process to identify all relevant parties (scientists, ethicists, community members, policy makers) who are impacted by or can impact the research [30]. |

| Participatory Team Science | An approach that formally engages public stakeholders (community members, patients) as active collaborators on the research team, providing essential lived experience and context [30]. |

Technical Support Center: Embedded Ethics FAQs & Troubleshooting

This guide provides practical solutions for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals implementing embedded ethics in AI-driven healthcare projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is Embedded Ethics and how does it differ from traditional ethics review processes?