Beyond Tuskegee: How a 40-Year Study Transformed Informed Consent and Research Ethics

This article examines the profound and enduring impact of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study on the ethics of informed consent in biomedical research.

Beyond Tuskegee: How a 40-Year Study Transformed Informed Consent and Research Ethics

Abstract

This article examines the profound and enduring impact of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study on the ethics of informed consent in biomedical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the study's historical context and ethical failures, traces the subsequent development of foundational ethical frameworks like the Belmont Report, analyzes persistent challenges in obtaining meaningful consent, and evaluates modern mechanisms for protecting human subjects. The analysis synthesizes how this pivotal case led to the institutionalization of ethical safeguards, including Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and mandated informed consent processes, and discusses their ongoing evolution in contemporary research.

The Tuskegee Study: A Foundational Failure in Research Ethics

Historical Context and Design of the USPHS Syphilis Study

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, conducted from 1932 to 1972, stands as a pivotal case in the history of research ethics. This whitepaper examines the study's historical context, methodological design, and procedural timeline, with particular emphasis on its role as a catalyst for the formalization of informed consent and ethical oversight in biomedical research. The analysis details how the study's 40-year progression—characterized by deliberate non-treatment and participant deception—directly influenced the creation of the Belmont Report, the establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), and contemporary regulatory frameworks governing human subject research. This review serves to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals about the critical importance of ethical foundations in clinical research.

The USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee was initiated in 1932 in Macon County, Alabama, against a backdrop of scientific inquiry into the natural progression of syphilis and pervasive racialized medical theories. The study was designed to document the pathology of untreated syphilis throughout the lifetime of subjects, ostensibly to complement a prior retrospective study conducted in Oslo, Norway, that had involved white males [1] [2]. A key impetus for the study was the prevailing, yet unproven, medical belief that syphilis manifested differently in African American individuals, allegedly affecting the cardiovascular system more prominently than the central nervous system, which was thought to be more characteristic of the disease in white populations [1] [2].

The study exploited the existing public health landscape of the rural South. A previous public health initiative funded by the Julius Rosenwald Fund had demonstrated a shockingly high syphilis prevalence rate of 36% within the Macon County African American community [1]. When the Great Depression led to the withdrawal of this funding, USPHS officials repurposed the established infrastructure and community connections to initiate a prospective study of untreated syphilis, fundamentally shifting the goal from treatment to observation [3].

Study Design and Methodological Framework

The Tuskegee Study's design and methodology were defined by the systematic selection of a vulnerable population, sustained deception, and the intentional withholding of effective treatment, all of which represented a profound failure of research ethics.

Participant Recruitment and Cohort Formation

Investigators enrolled a total of 600 African American sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama [4] [2]. The cohort was divided into two groups: 399 men diagnosed with latent syphilis formed the study group, while 201 men without the disease were designated as controls [4]. Recruitment strategies targeted a medically underserved and socioeconomically disadvantaged population, leveraging the trust associated with a local institution, the Tuskegee Institute [4] [5].

Table 1: Study Cohort Composition and Deception Tactics

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Total Participants | 600 African American men [2] |

| Syphilitic Group | 399 men with latent syphilis [4] |

| Control Group | 201 men without syphilis [4] |

| Recruitment Promise | Free treatment for "bad blood," free meals, burial insurance [2] [5] |

| Informed Consent | Not obtained; nature and risks of study deliberately withheld [4] |

| Key Deception | Told study was for "bad blood"; disguised placebos and diagnostic tests presented as "treatment" [2] |

Participants were deliberately misinformed about the study's purpose. The term "bad blood," a local colloquialism for various ailments including anemia and fatigue, was used to obscure the fact that the study focused on syphilis [2]. They were not told they were in a research study, nor were they informed of their syphilis diagnosis. Procedures like diagnostic spinal taps were misrepresented as "special free treatment" [2].

Withholding of Treatment and Active Prevention of Care

A defining and ethically catastrophic feature of the study was the persistent denial of effective treatment, which continued long after proven therapies became available.

- Initial Withholding (1930s): Even at the study's outset, some treatment was the standard of care. While participants were given ineffective minerals and topical ointments, effective, though toxic, arsenic-based drugs (e.g., Salvarsan) were withheld [6] [2].

- Withholding of Penicillin (Post-1947): After penicillin was established as the standard, safe, and effective cure for syphilis in the mid-1940s, researchers systematically prevented participants from accessing it [4] [2]. The USPHS went so far as to intervene with the military during World War II to ensure that 256 study subjects who had been diagnosed with syphilis at draft induction centers were not treated [2]. They also actively prevented participants from enrolling in other public health "rapid treatment centers" established to eradicate the disease [2] [5].

The study continued under these conditions for 40 years, based on repeated internal reviews that prioritized the collection of autopsy data over the lives and health of the participants [5].

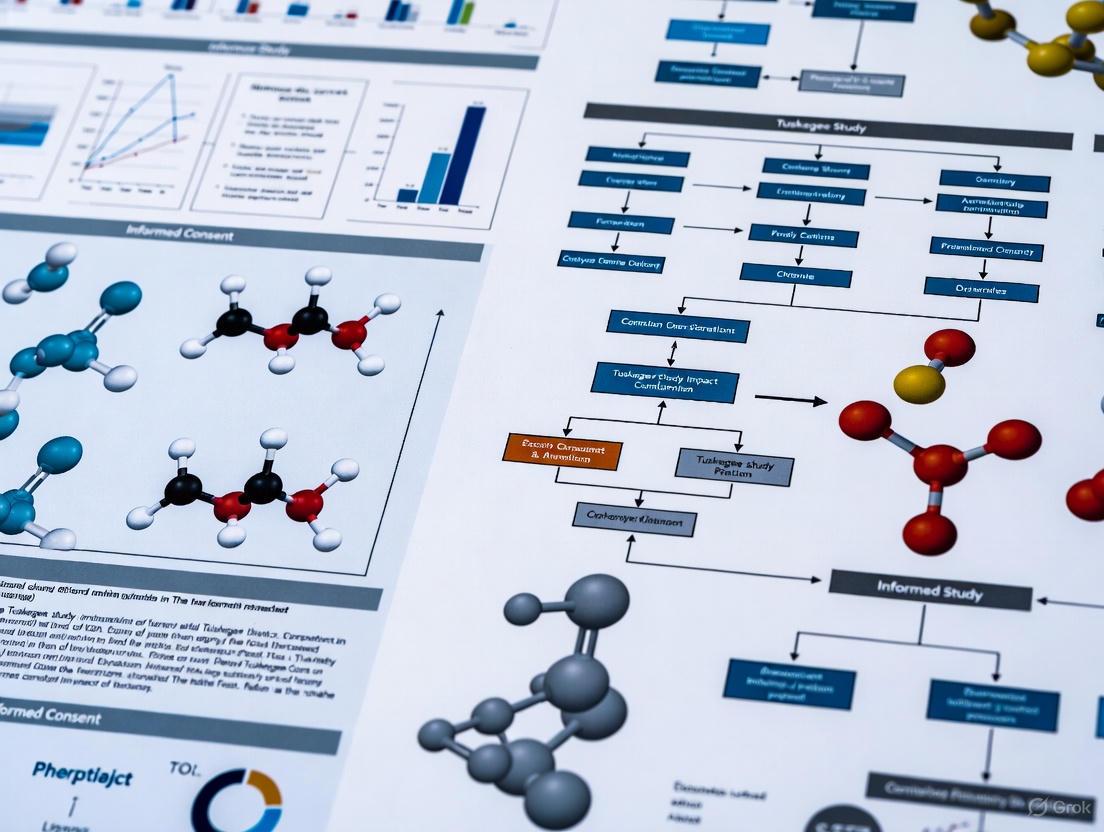

Visualizing the Study Timeline and Ethical Failures

The following diagram maps the key milestones and major ethical breaches that defined the 40-year duration of the USPHS Syphilis Study.

Diagram 1: Chronology of the USPHS Syphilis Study and its aftermath.

Research Reagents and Methodological Components

While the Tuskegee Study was an observational clinical study rather than a laboratory experiment, its "methodology" relied on several key components and deceptive practices.

Table 2: Key Methodological Components and Their Function in the Study

| Component | Function in the Study Context |

|---|---|

| Diagnostic Serological Tests | Used to identify and confirm syphilis infection during enrollment and to monitor disease progression throughout the study [2]. |

| Placebo (Disguised) | Inert substances (e.g., pink pills) given to participants to maintain the illusion of treatment, fostering continued participation under false pretenses [2]. |

| Spinal Tap (Lumbar Puncture) | A diagnostic procedure presented to participants as a "special free treatment," used to gather data on neurological involvement of syphilis [2]. |

| Patient Tracking System | Detailed records and local coordination (notably by Nurse Eunice Rivers) were used to monitor participants and actively prevent them from receiving syphilis treatment elsewhere [1] [5]. |

| Autopsy Protocol | A central objective of the study; researchers offered burial stipends to secure permission for autopsies, aiming to collect pathological data on the effects of untreated syphilis at death [1] [2]. |

Impact on Research Ethics and Informed Consent

The public exposure of the Tuskegee Study in 1972 triggered immediate outrage and led to direct congressional action [5]. This catalyzed a fundamental restructuring of the oversight system for research involving human subjects, formalizing the principles of informed consent and ethical review.

The Belmont Report and Its Ethical Principles

In 1974, the National Research Act established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [7] [3]. This commission produced the Belmont Report in 1979, which articulates three core ethical principles that now govern all federally funded research in the United States [7] [3]:

- Respect for Persons: This principle mandates that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and that persons with diminished autonomy (e.g., due to illness, poverty, or education) are entitled to protection. It is operationalized through the process of informed consent, requiring that participants voluntarily agree to research participation based on a clear understanding of the risks, benefits, and procedures involved [1] [3].

- Beneficence: This principle imposes an obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize potential harms. In practice, this requires a systematic risk-benefit assessment to ensure that the risks to subjects are justified by the anticipated benefits [3].

- Justice: This principle requires the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research. It demands that vulnerable populations, such as those targeted in the Tuskegee Study, not be disproportionately selected for research due to their availability or compromised position, but rather that the populations that bear the burdens of research should also be the ones to enjoy its benefits [3].

Institutionalization of Oversight: IRBs and Regulations

The Belmont Report provided the ethical foundation for concrete regulatory changes. A key outcome was the mandatory creation and use of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) [7] [5]. Federal law now requires that all research involving human subjects conducted or funded by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) be reviewed and approved by an IRB to ensure that it meets ethical standards, including the adequacy of the informed consent process [7]. The Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (the "Common Rule") was subsequently adopted by multiple federal agencies, creating a unified framework for human subject protection [7].

The USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee provides a stark, historical lesson on the catastrophic consequences of divorcing scientific inquiry from fundamental ethical principles. Its 40-year history of deception, racial targeting, and deliberate non-treatment represents an extreme failure of researcher responsibility and government oversight. For contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the study is not a mere historical footnote but a foundational case that underscores the non-negotiable necessity of ethical rigor. The modern infrastructure of informed consent, IRB review, and the guiding principles of the Belmont Report are the direct legacy of this study, serving as critical safeguards to ensure that scientific pursuit never again comes at the cost of human dignity and rights.

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, universally known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, represents one of the most egregious violations of research ethics in modern history. Conducted from 1932 to 1972 in Macon County, Alabama, this 40-year study fundamentally breached the physician-researcher covenant through systematic deception, withheld treatment, and lack of consent from its 600 African American participants (399 with syphilis, 201 without) [4] [1]. The study's exposure in 1972 triggered profound ethical reckoning, culminating in the Belmont Report of 1979, which established foundational principles for human subjects research [3] [1]. For contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these core violations remains essential for maintaining ethical integrity in clinical trials and biomedical research. This analysis examines the specific methodological failures of Tuskegee within the context of their lasting impact on modern research governance, providing both historical perspective and contemporary application frameworks.

Experimental Background and Methodological Framework

Original Study Design and Objectives

The Tuskegee Study originated with the purported scientific aim of documenting the natural progression of untreated latent syphilis in African American males, based on the hypothesis that the disease manifested differently in Black individuals [6] [1]. The study design was observational rather than interventional, with researchers deliberately withholding established treatments to observe the disease's pathological course until death and autopsy [4].

Table 1: Tuskegee Study Participant Groups and Research Objectives

| Participant Group | Number Enrolled | Research Objective | Long-term Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syphilitic Group | 399 men with latent syphilis | Document natural progression of untreated syphilis | Development of severe complications including blindness, insanity, death |

| Control Group | 201 men without syphilis | Provide comparative baseline data | Risk of infection from untreated participants in community |

The study was conducted with the cooperation of the Tuskegee Institute and used the hospital's medical facilities, lending an air of legitimacy that facilitated the deception of participants [1]. The research protocol deliberately violated standard medical practice even in 1932, as effective treatments using arsenic and bismuth compounds (metal therapy) were available, though potentially toxic, and were known to substantially reduce the risk of tertiary syphilis [6].

Methodological Flaws and Ethical Breaches

The Tuskegee Study's methodology contained fundamental flaws that transformed a scientific investigation into systematic exploitation. Participants were recruited through deception, being told they were receiving treatment for "bad blood" – a local term encompassing various ailments – rather than being enrolled in a study observing untreated syphilis [4] [1]. The research team, including nurse Eunice Rivers who served as a trusted authority figure, actively prevented participants from accessing treatment, including directing other healthcare providers to deny penicillin to study subjects after it became the standard of care in 1947 [1]. This methodology persisted despite the 1964 publication of results from the first 30 years of observation and internal complaints from USPHS staff [6].

Diagram 1: Ethical Violation Pathways in the Tuskegee Study. This diagram illustrates how core ethical violations were implemented and their consequent impacts on participants and research systems.

Core Ethical Violations: Analytical Assessment

Systematic Deception and Coercion

The Tuskegee Study employed multilayered deception throughout its 40-year duration. Participants were deliberately misinformed about their medical condition, being told they were being treated for "bad blood" rather than being observed for untreated syphilis [4] [1]. This deception extended to procedures, with painful diagnostic interventions like spinal taps described as "special free treatment" [1]. The researchers created a comprehensive illusion of therapeutic care by providing non-specific medications, vitamins, and transportation to the study site, reinforcing participant trust while actively denying actual treatment [8].

The study further employed systematic coercion by leveraging the economic vulnerability of the participant population. During the Great Depression and subsequent decades, the offer of "free medical care," burial insurance, and other indirect benefits represented significant economic inducements that compromised voluntary participation [6] [8]. This was particularly problematic given that the men were primarily poor, uneducated sharecroppers with limited access to healthcare and limited literacy, creating a power imbalance that precluded meaningful dissent [6].

Withheld Treatment and Therapeutic Abandonment

The most medically grievous violation occurred through the deliberate withholding of established treatments. Even when penicillin became widely available as a safe, effective cure for syphilis in the mid-1940s, researchers actively prevented participants from receiving it [4] [9]. This decision continued for 25 years despite the known devastating progression of untreated syphilis, which includes cardiovascular complications, neurological deterioration, blindness, and premature death [6].

Table 2: Timeline of Withheld Treatment in Tuskegee Study

| Year | Medical Context | Study Action | Ethical Breach |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | Arsenic/bismuth treatments available | Treatment withheld despite known efficacy | Denial of standard care |

| 1945 | Penicillin established as effective cure | Penicillin deliberately withheld from participants | Therapeutic abandonment |

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code establishes informed consent | Study continues without protocol changes | Disregard for emerging ethical standards |

| 1969 | CDC review acknowledges lack of benefit | Study permitted to continue | Institutional complicity |

| 1972 | Public exposure forces study termination | Remaining participants finally treated | 40 years of preventable harm |

The researchers justified continued nontreatment through scientific rationalization, arguing that the study population would likely have remained untreated due to poverty and limited healthcare access regardless of the study [6]. This reasoning ignored the active role researchers played in preventing treatment, including intercepting participants who sought care through other channels and collaborating with local physicians to deny penicillin [1]. The harm extended beyond participants to their families, with documentation of wives contracting syphilis and children born with congenital syphilis [4].

Absence of Informed Consent

The Tuskegee Study was conducted without any meaningful informed consent process. Participants were never informed about their syphilis diagnosis, the study's true purpose, or the risks of nontreatment [4]. This fundamental violation was compounded by researchers' deliberate use of misleading terminology and failure to explain procedures' actual nature [1]. The consent process entirely lacked comprehension and voluntariness – two essential components of ethical research participation [3].

This violation persisted despite the establishment of formal informed consent requirements in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and the U.S. adoption of these standards in subsequent years [3]. Internal critiques, such as the 1965 objection from Dr. Irwin Schatz, were dismissed without substantive review of the consent issue [1]. When the study was reviewed by a PHS panel in 1969, the complete absence of informed consent was noted but deemed insufficient to terminate the research [6].

Modern Research Ethics: Post-Tuskegee Framework

Regulatory and Policy Responses

The exposure of the Tuskegee Study directly catalyzed the development of modern research ethics governance. The National Research Act of 1974 established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which produced the landmark Belmont Report in 1979 [3] [1]. This foundational document articulated three core principles that continue to govern human subjects research:

- Respect for Persons: Recognition of individual autonomy and protection for persons with diminished autonomy, operationalized through informed consent [3]

- Beneficence: The obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harms, implemented through systematic risk-benefit assessment [10]

- Justice: Equitable distribution of research benefits and burdens, ensuring vulnerable populations are not disproportionately targeted [1]

The Belmont Report's principles were codified into federal regulations (45 CFR 46), establishing Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) as mandatory oversight bodies for human subjects research [3]. These regulations established specific requirements for informed consent documentation, including the purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives to participation [10].

Contemporary Ethical Protocols and Implementation

Modern clinical research operates within a comprehensive ethical framework that directly addresses Tuskegee's violations through procedural safeguards and oversight mechanisms.

Table 3: Modern Safeguards Against Tuskegee Violations

| Tuskegee Violation | Modern Research Safeguard | Implementation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Informed Consent | Comprehensive Consent Process | Detailed consent forms, comprehension assessment, witness verification |

| Withheld Treatment | Favorable Risk-Benefit Ratio | IRB review, ongoing safety monitoring, data safety monitoring boards |

| Deception | Limited/Justified Deception | Debriefing requirements, scientific justification, IRB approval |

| Vulnerability Exploitation | Additional Protections | Special population regulations, community consultation |

| Unethical Continuation | Independent Oversight | IRB continuing review, stopping rules, interim analysis |

For drug development professionals, these safeguards translate into specific methodological requirements. Clinical trial protocols must now include detailed informed consent documents, data safety monitoring plans, predefined stopping rules, and fair subject selection procedures [10]. The informed consent process requires researchers to provide information in understandable language, assess participant comprehension, and document consent without coercion [3]. Contemporary ethics also emphasize post-trial responsibilities, including providing effective treatments to placebo groups after trial completion – a direct response to Tuskegee's therapeutic abandonment [11].

Diagram 2: Modern Research Ethics Framework. This diagram illustrates the application of Belmont Report principles through specific applications and implementation mechanisms in contemporary research.

Research Reagent Solutions: Ethical Framework Components

For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, maintaining ethical integrity requires specific "reagents" in their methodological toolkit. These components function as essential resources for designing and conducting ethically sound research.

Table 4: Essential Ethical Framework Components for Clinical Research

| Toolkit Component | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent Templates | Standardize disclosure of study purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives | Ensure comprehensive information transfer and documentation |

| IRB Submission Protocols | Facilitate ethical review of study design, participant selection, and risk mitigation | Provide independent oversight and accountability |

| Data Safety Monitoring Plans | Establish procedures for ongoing risk assessment and unblinding criteria | Protect participant welfare during trial conduct |

| Vulnerability Assessment Tools | Identify potentially coercive factors in participant population | Implement additional safeguards for vulnerable groups |

| Community Engagement Frameworks | Facilitate consultation with representative stakeholders | Enhance cultural sensitivity and equitable participation |

These toolkit components operationalize the ethical principles established in response to Tuskegee, providing practical implementation of theoretical frameworks [10]. For example, modern informed consent processes must address not only study procedures but also potential conflicts of interest, compensation for injury, and withdrawal procedures – elements conspicuously absent from Tuskegee [12]. Similarly, contemporary protocols require scientific justification for any deception and mandatory debriefing procedures when deception is methodologically necessary [10].

Contemporary Challenges and Evolving Applications

Despite comprehensive ethical frameworks, modern research faces ongoing challenges that echo Tuskegee's legacy. Recent analyses of early-phase clinical trials reveal persistent ethical concerns, including evidence that participants frequently misunderstand the primarily safety-focused nature of Phase I studies and therapeutic misconceptions remain prevalent [8]. Contemporary studies also document how abrupt trial termination, particularly when driven by funding constraints rather than scientific considerations, can violate ethical principles by negating the value of participant contributions and breaking trust [13].

The legacy of mistrust engendered by Tuskegee continues to impact medical research participation, particularly among African American communities. Research published by Stanford University demonstrates that disclosure of the Tuskegee Study in 1972 correlated with a 1.4-year decline in life expectancy among African American men, potentially accounting for approximately 35% of the 1980 life expectancy gap between black and white men [9]. This underscores the real-world consequences of ethical violations and the continued importance of building trustworthy research practices.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study remains a pivotal case study in research ethics precisely because its core violations – deception, withheld treatment, and lack of consent – represent fundamental breaches of the researcher-participant covenant. For contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these violations provides essential guidance for ethical decision-making in increasingly complex research environments. The regulatory frameworks established in response to Tuskegee, particularly the Belmont Principles and IRB oversight system, provide critical protections but require ongoing vigilance and contextual application. Modern challenges including ensuring diverse participation, maintaining trust, and adapting to technological advancements continue to test our ethical commitments. By integrating the lessons of Tuskegee into both institutional policies and individual practice, the research community honors its fundamental obligation to protect human dignity while advancing scientific knowledge.

The Role of Scientific Racism and Vulnerable Populations

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male stands as a profound illustration of how scientific racism enables the systematic exploitation of vulnerable populations in medical research. Conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972, this 40-year study deliberately withheld effective treatment from 399 African American men with syphilis to observe the natural progression of the disease, despite the 1940s availability of penicillin as a proven cure [4] [14]. The study's enduring significance lies not only in its ethical violations but in its explicit connection to a longer historical tradition of scientific racism—the co-opting of scientific authority to justify racial inequality and biological determinism [15]. This whitepaper examines the Tuskegee Study within this broader context, analyzing its impact on the development of contemporary informed consent ethics and research protections for vulnerable populations. We further explore how the legacy of such abuses continues to influence medical mistrust and participation in clinical research today, providing researchers and drug development professionals with critical insights for conducting ethical research with diverse populations.

Historical Context: Scientific Racism and Medical Research

Scientific racism provides the essential ideological foundation that made studies like Tuskegee possible. This framework involves using pseudoscientific methods to "prove" white biological superiority and justify racial inequality [15]. Its historical manifestations include:

- Polygenism: The 19th-century theory, promoted by figures like Harvard's Louis Agassiz, that human races were distinct species, supported by pseudoscientific methods like craniometry [15].

- Eugenics Movements: The application of Darwinian concepts to social hierarchy, claiming that social inequalities reflected natural biological superiority [16].

- Flawed Social Science: Studies using biased methodologies that attributed high imprisonment rates or intelligence test results to innate racial characteristics while ignoring social, economic, and political factors [15].

This historical context normalized the exploitation of vulnerable populations by providing supposed scientific justification for their differential treatment. The Tuskegee Study emerged directly from this tradition, operating on the unproven assumption that "different races experienced diseases differently" [3]. Researchers believed they could observe the "ravages of untreated syphilis in Black populations" as a distinct biological phenomenon, separate from the social and economic conditions that created health disparities [3].

Table 1: Historical Examples of Scientific Racism in Research

| Time Period | Practice/Theory | Key Proponents | Impact on Research Ethics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19th Century | Polygenism | Louis Agassiz, Samuel Morton | Established hierarchy of human races as biological fact |

| Early 20th Century | Eugenics | Francis Galton | Justified experimentation on "inferior" populations |

| 1932-1972 | Tuskegee Syphilis Study | U.S. Public Health Service | Demonstrated consequences of unchecked scientific racism |

| 1990s | Genetic Behavior Studies | Various academic institutions | Continued exploitation of vulnerable minorities [17] |

The Tuskegee Study: Experimental Protocol and Ethical Violations

Study Design and Methodology

The Tuskegee Study's experimental protocol reflects systematic ethical failures grounded in scientific racism:

Subject Recruitment: Researchers recruited 600 African American men—399 with latent syphilis and 201 without—from Macon County, Alabama, targeting a vulnerable population of poor, predominantly uneducated sharecroppers [4] [14]. Participants were deceived about the study's purpose, being told they were being treated for "bad blood," a colloquial term encompassing various ailments [14].

Data Collection Methods: The study employed multiple deceptive practices to maintain participant involvement and gather data:

- Lumbar Punctures: Performed under the guise of "special free treatment" rather than as diagnostic procedures [14].

- Autopsy Collection: Researchers promised burial stipends to secure autopsy permissions, understanding that "every darkey will leave Macon County" if they knew autopsies were required [14].

Withholding Treatment: The most egregious ethical violation occurred when researchers deliberately withheld known effective treatments:

- Penicillin: After penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis in 1947, researchers actively prevented participants from accessing it [4] [14].

- Active Intervention: Public Health Service staff instructed local physicians not to treat study participants and intervened with the military to prevent drafted subjects from receiving treatment [14].

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Elements in the Tuskegee Study

| Research Element | Function in Study | Ethical Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo Treatments | Vitamin tonics and aspirin administered to maintain deception of therapeutic benefit | Deliberate deception about nature of intervention |

| Diagnostic Lumbar Punctures | Cerebrospinal fluid collection to document neurosyphilis progression | Performed under false pretenses of being "spinal shots" as treatment |

| Penicillin (withheld) | Proven effective treatment available from 1940s onward | Actively withheld despite known efficacy and safety |

| Burial Stipends | Financial incentive to secure autopsy permissions | Exploited economic vulnerability and cultural burial practices |

Diagram 1: Tuskegee Study Methodology Flow

Impact on Research Ethics and Informed Consent

The exposure of the Tuskegee Study in 1972 prompted immediate public outrage and catalyzed fundamental reforms in research ethics, particularly in the domain of informed consent.

The Belmont Report and Ethical Frameworks

In direct response to Tuskegee, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research developed the Belmont Report in 1979, which established three core ethical principles for research [3]:

Respect for Persons: Recognizing the autonomy of individuals and requiring protection for those with diminished autonomy. This principle translates operationally into:

- Informed Consent: Requirements that information is comprehensive and comprehensible, participation is voluntary, and documentation procedures are rigorous [3].

- Special Protections: Additional safeguards for vulnerable populations (children, prisoners, individuals with diminished cognitive capacity).

Beneficence: The obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms, implemented through:

- Systematic Risk-Benefit Assessment: Thorough evaluation of potential risks and benefits before study initiation [3].

- Ongoing Monitoring: Continuous evaluation throughout the study duration.

Justice: The fair distribution of research burdens and benefits across society, addressing the Tuskegee exploitation by ensuring:

- Equitable Subject Selection: Protection against systematically selecting vulnerable populations for high-risk research [3].

- Benefits for Participating Populations: Research should benefit the same communities that bear the research burdens.

Diagram 2: Tuskegee's Impact on Research Ethics Framework

Institutional Oversight Mechanisms

The post-Tuskegee reforms established structural safeguards to prevent future abuses:

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): Required for all federally funded research to provide third-party oversight of study designs, informed consent processes, and risk-benefit analyses [3].

Federal Regulations: Codification of the Belmont Report principles into federal law (45 CFR 46), including specific subparts providing additional protections for vulnerable populations [3].

Contemporary Implications and Quantitative Evidence

Impact on Medical Trust and Health Outcomes

Recent research has quantified the lasting impact of the Tuskegee Study on medical mistrust and health outcomes within African American communities:

Reduced Healthcare Utilization: Following the 1972 disclosure of the study, older black men in geographic and cultural proximity to Tuskegee showed significantly lower utilization of both outpatient and inpatient medical care [18].

Mortality Effects: The disclosure was associated with a 1.4-year decline in life expectancy at age 45 for black men, explaining approximately 35% of the 1980 life expectancy gap between black and white men [18].

Persistent Mistrust: Qualitative studies identify mistrust of the healthcare system as a primary barrier to research participation among African Americans, with historical abuses like Tuskegee reinforcing ongoing systemic inequities [17].

Table 3: Quantitative Findings on Tuskegee's Legacy in Black Male Health

| Metric | Pre-1972 Trend | Post-1972 Change | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life Expectancy (Black men, 45+) | Narrowing racial gap | 1.4-year decrease | Explained 35% of racial mortality gap [18] |

| Medical Care Utilization | Increasing utilization | Significant reduction | Particularly for inpatient/outpatient care [18] |

| Willingness to Participate in Research | Not measured pre-1972 | Increased mistrust but not directly linked to participation [19] | Mistrust persists but doesn't always deter participation [17] [19] |

Complexities in the Trust-Participation Relationship

While mistrust remains significant, recent research reveals nuanced relationships:

Awareness vs. Participation: The Tuskegee Legacy Project found no direct association between awareness/knowledge of the Tuskegee Study and willingness to participate in biomedical research for Blacks or Whites, suggesting mistrust is more multifaceted and influenced by ongoing systemic factors [19].

Broader Historical Context: Mistrust stems from "more than Tuskegee"—including a longer history of medical exploitation and contemporary experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings [17].

Recommendations for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

Based on the historical legacy and contemporary evidence, we recommend these practices for ethical research:

Comprehensive Informed Consent Protocols: Implement truly transparent processes that address potential concerns about historical abuses without minimizing them.

Community-Engaged Research: Partner with community representatives throughout research design, implementation, and dissemination to build authentic trust.

Diversity in Research Teams: Increase representation of underrepresented minorities among investigators and clinical staff to reduce cultural barriers.

Ethical Study Closure Procedures: Develop participant-centered plans for ethical study termination, particularly important given recent concerns about politically motivated clinical trial closures that disproportionately affect marginalized populations [20] [13].

Systemic Reform Acknowledgment: Recognize that single studies like Tuskegee occur within broader systems of scientific racism that require ongoing structural reform.

The Tuskegee Study represents a critical case study in the intersection of scientific racism, vulnerable population research, and ethics reform. Its legacy demonstrates how historical abuses can generate persistent medical mistrust with measurable health consequences, while simultaneously catalyzing essential protections for research participants. For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this history is not merely an academic exercise but a professional imperative. By implementing truly ethical research practices that acknowledge this troubled history, the scientific community can work to rebuild trust and ensure that research advances health equity rather than exacerbating disparities. The principles established in response to Tuskegee—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—remain foundational guides for conducting research that honors the dignity and rights of all participants, particularly those from historically exploited communities.

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) from 1932 to 1972, represents one of the most egregious violations of medical ethics in modern history [2]. The study's objective was to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis in a cohort of 600 African American men—399 with the disease and 201 without [21]. The research was fundamentally flawed by the deliberate decision to withhold both diagnosis and treatment, even after penicillin became the standard of care in 1947 [2]. The study's termination did not result from internal ethical review but from the determined actions of a whistleblower, Peter Buxtun, whose disclosures ultimately exposed the experiment to public scrutiny and catalyzed its termination in 1972 [22]. This case established a critical precedent, demonstrating that sustained internal reporting mechanisms alone may be insufficient to halt unethical research and that public exposure often serves as the essential catalyst for systemic reform. The Tuskegee Study's legacy fundamentally reshaped the ethical landscape of human subjects research, placing informed consent at the center of regulatory frameworks [21] [23].

Experimental Protocol and Design Flaws

Original Study Methodology

The Tuskegee Study was designed as a prospective study to complement the retrospective Oslo Study of Untreated Syphilis [2]. The PHS recruited 600 impoverished African American sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama, under the pretext of providing free medical treatment for "bad blood," a local colloquialism for various ailments including syphilis, anemia, and fatigue [21] [2].

Key Methodological Components:

- Subject Pool: 600 African American males (399 with latent syphilis, 201 controls)

- Duration: 1932-1972 (40 years)

- Data Collection: Annual physical examinations, blood tests, and periodic spinal taps

- Deception: Participants were never informed of their syphilis diagnosis; spinal taps were misrepresented as "special free treatment" [22] [2]

- Incentives: Free medical exams, hot meals, burial insurance [22]

Withholding of Treatment

The most profound ethical failure occurred through the systematic withholding of treatment:

- Initial Phase (1932-1940s): Subjects received ineffective treatments such as aspirin, mineral supplements, and diagnostic procedures disguised as therapeutic interventions [2].

- Penicillin Era (Post-1947): Despite penicillin becoming widely available and established as the standard treatment for syphilis by 1947, researchers actively prevented participants from accessing treatment [2]. This included intervening with draft boards during World War II to prevent subjects who were called for military service from receiving treatment [22] [2].

Table 1: Tuskegee Study Timeline and Key Methodological Failures

| Year | Event | Ethical Violation |

|---|---|---|

| 1932 | Study initiated | Deception about study purpose |

| 1932-1940 | Mercury, arsenic "treatment" provided | Known ineffective treatments administered |

| 1943 | Penicillin recognized as effective treatment | Active withholding of effective treatment begins |

| 1947 | Penicillin becomes standard care | Systematic denial of standard care implemented |

| 1965-1966 | Peter Buxtun's first internal complaints | Institutional dismissal of ethical concerns |

| 1972 | Public media exposure | Study termination forced |

The Whistleblower Protocol: Peter Buxtun's Exposure Strategy

Peter Buxtun, a 27-year-old venereal disease investigator for the PHS in San Francisco, learned about the Tuskegee Study in 1966 and initiated a multi-year disclosure process that followed what would now be recognized as established whistleblower protocols [22] [24].

Internal Reporting Phase (1966-1968)

Buxtun's initial approach followed proper internal channels:

- Evidence Gathering: He conducted independent investigation into the study's procedures and documentation [22].

- Formal Written Complaint: In 1966, he authored a detailed report drawing explicit comparisons between the Tuskegee Study and the Nazi medical experiments prosecuted at Nuremberg, highlighting the violation of the Nuremberg Code [22].

- Chain of Command Engagement: He presented his concerns to PHS supervisors and was subsequently flown to Atlanta to confer with senior PHS doctors overseeing the study [22].

- Persistent Follow-up: After receiving no substantive response, Buxtun submitted a second formal complaint in 1968, emphasizing that subjects were "quite ignorant of the effects of untreated syphilis" and noting the study represented "political dynamite" due to its exclusively African American subject pool [22].

Escalation to External Channels

When internal mechanisms failed, Buxtun escalated his approach:

- Media Engagement: After leaving the PHS and entering law school, Buxtun provided documents to a reporter from the Washington Star in 1972 [22] [24].

- Anonymity Strategy: Initially, Buxtun worked through the journalist while maintaining some degree of confidentiality, though he eventually testified publicly [24].

- Legal Preparation: His legal education equipped him with the framework to understand the regulatory violations and potential liability, strengthening his position when engaging with media and government investigators [24].

Table 2: Whistleblower Strategy Analysis: Internal vs. External Approaches

| Phase | Actions Taken | Institutional Response | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal (1966) | Formal report to PHS supervisors | Report dismissed as "trash"; Buxtun chastised | No action taken; study continues |

| Internal (1968) | Second formal complaint emphasizing racial implications | Blue-ribbon panel convened; votes to continue study | Institutional reinforcement of study |

| External (1972) | Documents provided to Associated Press | Story breaks nationally July 25, 1972 | Public outrage; study terminated within months |

Quantitative Impact Assessment

The consequences of the Tuskegee Study, both in human toll and regulatory impact, can be measured through multiple quantitative dimensions.

Table 3: Documented Harm to Study Participants and Their Families

| Category of Harm | Number Affected | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Death directly from syphilis | 28 | 7.0% of infected |

| Death from related complications | 100 | 25.1% of infected |

| Wives infected | 40 | - |

| Children with congenital syphilis | 19 | - |

| Survivors at study termination (1972) | 74 | 18.5% of original cohort |

The statistical outcomes revealed a 23% higher death rate among the infected men compared to the control group, a finding that the 1968 PHS review panel acknowledged yet still voted to continue the study [22].

The Informed Consent Framework: Post-Tuskegee Reforms

The exposure of the Tuskegee Study directly catalyzed the development of modern informed consent regulations and ethical oversight mechanisms. Contemporary informed consent in clinical research rests on three critical elements, each of which was violated in Tuskegee [23]:

Core Elements of Valid Informed Consent

Voluntarism: The participant's decision must be free from coercion, undue influence, or deception [23]. The Tuskegee participants were coerced through poverty and deceived about their condition.

Information Disclosure: Participants must receive comprehensive information about the study purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives [23]. Tuskegee participants were deliberately misinformed about their diagnosis and the nature of procedures.

Decision-Making Capacity: Participants must possess the cognitive ability to understand the information and make a reasoned decision [23]. The exploited socioeconomic status of the Tuskegee participants compromised this capacity.

Regulatory Transformation

The public exposure of Tuskegee led to concrete regulatory changes:

- Belmont Report (1979): Established ethical principles for human subjects research: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice [2].

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): Mandated review of all federally-funded human subjects research [2] [25].

- Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP): Created within the Department of Health and Human Services to oversee research compliance [2].

Diagram 1: Ethical Framework Development Post-Tuskegee

Modern Research Ethics: Protocols and Compliance

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Contemporary ethical research requires what might be termed "procedural reagents" – essential components that ensure ethical integrity:

Table 4: Essential Ethical Compliance Components in Modern Research

| Component | Function | Regulatory Basis |

|---|---|---|

| IRB Approval | Independent ethical review of study design | Belmont Report, FDA Regulations |

| Informed Consent Documentation | Verifiable proof of participant understanding | 21 CFR 50, ICH GCP |

| Data Safety Monitoring Board | Ongoing safety oversight during trial | NIH Policy, FDA Guidance |

| Adverse Event Reporting System | Timely identification of unforeseen risks | FDA Regulations |

| Confidentiality Safeguards | Protection of participant privacy | HIPAA, Privacy Act |

Valid Informed Consent Workflow

The modern informed consent process represents a systematic approach to ethical participant enrollment:

Diagram 2: Modern Informed Consent Workflow

The termination of the Tuskegee Study through whistleblower action established an enduring legacy in biomedical research ethics. Peter Buxtun's persistence demonstrated that ethical research requires not just formal protocols but also courageous individuals willing to challenge institutional power. The regulatory frameworks established in response to Tuskegee—particularly the emphasis on informed consent as an ongoing process rather than a single signature—continue to shape clinical trial design and implementation [23] [26].

The Tuskegee experience particularly highlighted the vulnerability of marginalized populations in research and led to specific protections for prisoners, children, and other vulnerable groups. Furthermore, the case established whistleblowing as a crucial, though personally risky, mechanism for accountability in scientific research. The continued evolution of ethical standards in human subjects research remains fundamentally informed by the lessons of Tuskegee, ensuring that the sacrifices of the study participants ultimately contributed to stronger protections for all research subjects.

The 1997 Presidential Apology and National Legacy

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) from 1932 to 1972, stands as one of the most infamous examples of unethical research in history. The study, which involved 600 African American men—399 with syphilis and 201 without—aimed to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis [4] [27]. The participants were deliberately misled; they were told they were being treated for "bad blood," a local term for various ailments, but in reality, they received no effective treatment even after penicillin became the standard cure in the 1940s [14] [28]. The study's eventual public exposure in 1972 sparked widespread outrage and led to major reforms in research ethics [4]. On May 16, 1997, President Bill Clinton issued a formal presidential apology, acknowledging the U.S. government's role in this deeply immoral study and marking a critical moment in the national legacy of confronting research abuses [29] [27]. This apology served as a pivotal acknowledgment of past wrongs and a commitment to ensuring such ethical failures would not be repeated, fundamentally shaping the modern framework of informed consent and ethical oversight in research.

The Tuskegee Study: Experimental Design and Ethical Failures

Original Protocol and Methodological Flaws

The initial design of the Tuskegee Study was presented as a "study in nature" to observe the natural history of untreated syphilis in African American men, purportedly because Macon County, Alabama, offered a "natural laboratory" with a high prevalence of the disease [14] [28]. The research was conceived by Dr. Taliaferro Clark of the USPHS Venereal Disease Division and was intended to last 6 to 8 months [6] [14]. The methodology involved enrolling 600 Black men, with and without syphilis, who were subjected to periodic blood tests, x-rays, and spinal taps [28]. A key deceptive practice involved presenting diagnostic procedures as therapeutic interventions; for instance, lumbar punctures were described as "spinal shots" offered as a "special treatment" [14]. The researchers' commitment to obtaining pathological confirmation of the disease process led to a gruesome emphasis on autopsies, with the USPHS offering burial insurance as an incentive for families to consent to postmortem examinations [14].

Table 1: Tuskegee Study Participant Groups and Outcomes

| Category | Number of Participants | Description | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syphilitic Group | 399 | Men with latent or late syphilis at enrollment | By 1969, at least 28-100 men had died directly from syphilis complications [14]. |

| Control Group | 201 | Men without syphilis at enrollment | Served as a comparison group; some were transferred to the syphilitic group if they later developed the disease [28]. |

| Survivors (1972) | 74 | Men alive when the study ended | Only 74 of the original 600 participants were still alive when the study was terminated in 1972 [28]. |

| Secondary Victims | At least 59 | Wives and children infected as a consequence | 40 wives were infected, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis [28]. |

Active Withholding of Treatment and Escalation of Harm

The study's most profound ethical breach was the systematic withholding of effective treatment. When penicillin became the standard of care for syphilis in the mid-1940s, the researchers actively prevented participants from accessing it [14] [28]. This involved specific interventions to maintain the untreated status of the cohort. The USPHS provided lists of participants to local physicians and the Alabama Health Department with instructions not to treat them [28]. During World War II, when some men were drafted and diagnosed with syphilis through military medical exams, the researchers intervened to have them removed from the army rather than allow them to be treated [30] [28]. A key figure in ensuring participant retention and non-treatment was a Black nurse, Eunice Rivers, who was employed to drive participants to appointments, deliver placebos, and even retrieve men who sought treatment elsewhere [30]. These actions transformed the study from a passive observation into an active, harmful intervention that directly caused unnecessary suffering and death.

The Path to Apology: Exposure, Outrage, and Reconciliation

Whistleblower and Public Exposure

The Tuskegee Study was terminated only after a whistleblower, Peter Buxtun, a former venereal disease investigator for the USPHS, leaked information about the unethical experiment to a reporter [14] [27]. The story was published on the front page of the New York Times on July 25, 1972, triggering immediate public outrage and leading to congressional hearings [27]. Buxtun had previously raised ethical concerns internally within the USPHS on multiple occasions, but his complaints were dismissed, and the study was allowed to continue [14]. The subsequent public scandal and political pressure forced the government to convene an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, which ultimately recommended the study be ended immediately [4]. This chain of events highlights the critical role of individual conscience and a free press in uncovering and halting unethical research practices.

Legal Recourse and the 1997 Presidential Apology

The exposure of the study led to a class-action lawsuit filed by attorney Fred Gray on behalf of the participants and their families [4] [27]. In 1974, the U.S. government agreed to an out-of-court settlement totaling $10 million, which was distributed to surviving participants and the heirs of deceased subjects [4]. The settlement also mandated that the government provide lifetime medical benefits to the surviving participants and their infected family members [30]. While the settlement provided some material compensation, the survivors and their families continued to seek moral restitution in the form of a formal apology. This was finally delivered on May 16, 1997, by President Bill Clinton [29]. In a ceremony attended by five of the eight surviving study participants, President Clinton stated, "The United States government did something that was wrong — deeply, profoundly, morally wrong. It was an outrage to our commitment to integrity and equality for all our citizens" [29] [30]. He directly acknowledged the racism inherent in the study, saying, "I am sorry that your federal government orchestrated a study so clearly racist" [29]. The apology was a crucial step in a national process of reconciliation and acknowledgment of a grave historical injustice.

Table 2: Timeline of Key Events from Study Termination to Presidential Apology

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Study exposed by Jean Heller of the Associated Press | Public revelation led to termination of the study and public outrage [4] [27]. |

| 1973 | Report by the Ad Hoc Advisory Panel | Officially condemned the study and led to major policy changes [4]. |

| 1974 | National Research Act passed | Created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects and mandated IRB review [7]. |

| 1974 | $10 million out-of-court settlement | Provided monetary compensation to participants and their families [4]. |

| 1997 | Presidential Apology by Bill Clinton | Formal acknowledgment of government wrongdoing and moral responsibility [29]. |

Impact on Research Ethics and Informed Consent Protocols

Regulatory Framework: From National Research Act to Belmont Report

The Tuskegee Study's exposure directly catalyzed the creation of a formal regulatory system for human subjects research in the United States. The National Research Act of 1974 established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [7]. This commission was tasked with identifying the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of research involving human subjects. In 1979, the commission published the Belmont Report, a foundational document that outlines three core ethical principles [3] [7]:

- Respect for Persons: This principle acknowledges the autonomy of individuals and requires that those with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. It is operationalized through the process of informed consent.

- Beneficence: This principle entails an obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize potential harms to research subjects. It is applied through a systematic assessment of risks and benefits.

- Justice: This principle requires that the benefits and burdens of research be distributed fairly. It addresses the need to avoid exploitation of vulnerable populations, a direct response to the exploitation of poor, African American men in Tuskegee.

The Belmont Report's principles were translated into federal regulations, mandating Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to oversee and approve all research involving human subjects [3] [7]. IRBs are charged with ensuring that research protocols adhere to the ethical standards of informed consent, favorable risk-benefit ratio, and equitable subject selection.

Diagram: The Regulatory Pathway from Tuskegee to Modern Research protections. The exposure of the Tuskegee Study directly led to a series of federal actions that codified core ethical principles into enforceable regulations, including mandatory IRB review and informed consent.

Operationalizing Ethics: The Scientist's Toolkit for Human Subjects Research

The legacy of Tuskegee is embedded in the daily practices of modern researchers. The following toolkit details the essential components, derived from the Belmont Report, that are now mandatory for ethical research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Ethical Research

| Tool | Function | Ethical Principle Applied |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent Document | A comprehensive document that explains the study's purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives in understandable language. Ensures voluntary participation. | Respect for Persons [3]. |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | An independent committee that reviews, approves, and monitors research protocols to ensure ethical standards and regulatory compliance are met. | Beneficence, Justice [3] [7]. |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment | A systematic analysis performed by researchers and reviewed by the IRB to ensure that risks to subjects are minimized and are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits. | Beneficence [3]. |

| Subject Selection Framework | Guidelines for the equitable selection of research subjects to ensure that vulnerable populations are not disproportionately targeted for high-risk research without a compelling scientific reason. | Justice [3]. |

| Data Safety and Monitoring Plan | A protocol for ongoing monitoring of collected data to ensure participant safety and the validity and integrity of the study. | Beneficence [7]. |

Enduring Challenges and the Imperative for Vigilance

Despite these significant reforms, the Tuskegee legacy presents ongoing challenges. The study is frequently cited as a primary driver of medical mistrust, particularly among African Americans, which can hinder participation in clinical research and complicate public health efforts [31] [27]. Research has shown that awareness of the Tuskegee Study is significantly higher among Blacks than Whites, and this awareness can influence perceptions of research participation [31]. Furthermore, modern revisionist accounts have attempted to rationalize the study's unethical conduct, often by exaggerating the uncertainties of available treatments at the time or downplaying the deliberate deception involved [6]. These revisionist arguments underscore the persistent need for rigorous historical accuracy and moral clarity in the scientific community. The central lesson of Tuskegee is the requirement for constant vigilance, the courage to speak out against unethical practices, and the institutional will to act, ensuring that scientific progress never again comes at the cost of fundamental human rights [14].

From Scandal to Safeguards: The Birth of Modern Ethical Frameworks

The National Research Act of 1974 and its Mandate

The U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, conducted from 1932 to 1972, stands as a profound failure in research ethics. This study, which intentionally withheld effective treatment from 400 African American men with syphilis to observe the natural progression of the disease, directly catalyzed the creation of the National Research Act of 1974 [4] [14]. The public revelation of the Tuskegee study in 1972 exposed a critical absence of federal safeguards for human research subjects, generating widespread outrage and prompting immediate congressional action [32] [6]. The National Research Act (NRA), signed into law by President Richard Nixon on July 12, 1974, was the direct legislative response to this ethical breach, establishing a formal system to protect human subjects in biomedical and behavioral research [33]. This legislation marked a pivotal turn in the United States, transitioning research ethics from a matter of professional discretion to a matter of federal law, fundamentally reshaping the relationship between researchers, participants, and the institutions that govern them. The Act's mandate was clear: to ensure that the ethical violations epitomized by the Tuskegee study—including the lack of informed consent, deception of participants, and the withholding of available treatment—would not be repeated [4] [28].

Core Mandates of the National Research Act

The National Research Act established a comprehensive framework for ethical research through two primary mechanisms: the creation of a national commission to define ethical principles and the institutionalization of a review process for federally conducted or funded research.

Establishment of the National Commission

The NRA established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [7] [33]. This multidisciplinary body was tasked with a critical mission: to identify the basic ethical principles that should govern human subjects research and to develop guidelines to ensure that research is conducted in accordance with those principles [32]. The Commission was specifically directed to address several contentious issues, including research involving fetuses, children, prisoners, and individuals with mental disabilities [32]. The most enduring product of this Commission was The Belmont Report, published in 1979, which articulated three fundamental ethical principles:

- Respect for Persons: This principle acknowledges the autonomy of individuals and requires that individuals with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. It is operationalized in the research process through the requirement for informed consent [3].

- Beneficence: This principle entails an obligation to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms. In research, this is applied through a careful assessment of the risks and benefits of a study [3].

- Justice: This principle requires that the benefits and burdens of research be distributed fairly. It demands that vulnerable populations are not selected for research simply because of their availability or manipulability, a direct response to the exploitation of poor, African American sharecroppers in the Tuskegee study [6] [3].

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and Informed Consent

A second key mandate of the NRA was the formalization of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) process [7] [33]. The Act required that any entity applying for a federal grant or contract involving human subjects research must demonstrate that it has an IRB to review and approve the proposed research protocol [32]. The law mandated that researchers obtain voluntary informed consent from all persons taking part in studies done or funded by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW), now the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) [7]. This requirement was a direct countermeasure to the deceit practiced in the Tuskegee study, where participants were misled into believing they were receiving treatment for "bad blood" [4] [28].

Table 1: Core Ethical Principles of The Belmont Report and Their Application

| Ethical Principle | Meaning | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Recognizing the autonomy of individuals and protecting those with diminished autonomy. | Informed Consent Process |

| Beneficence | The obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harms. | Systematic Risk-Benefit Assessment |

| Justice | The fair distribution of the benefits and burdens of research. | Equitable Selection of Subjects |

The diagram below illustrates the structured ethical review process for research protocols mandated by the National Research Act.

Quantitative Impact: Settlement Data and Regulatory Timeline

The quantitative repercussions of the Tuskegee Study are reflected in the legal settlement and the subsequent regulatory milestones it triggered. Following the public exposure of the study, the NAACP launched a class-action lawsuit, which was settled out of court in 1974 for \$10 million [28]. The distribution of these funds to the participants and their families is detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: 1974 Out-of-Court Settlement Distribution for Tuskegee Study Participants [4]

| Category of Recipient | Number of Men | Settlement Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Living syphilitic group participants | 399 (initial) | \$37,500 each |

| Heirs of deceased syphilitic group participants | Not specified | \$15,000 each |

| Living control group participants | 201 (initial) | \$16,000 each |

| Heirs of deceased control group participants | Not specified | \$5,000 each |

The regulatory timeline below charts the key ethical and legislative responses that unfolded in the wake of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, culminating in the National Research Act and its seminal outputs.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Ethical Research

The National Research Act and its progeny provide the foundational elements for the modern system of human research protections. For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, adherence to this framework is non-negotiable. The following table details the key "research reagents" for ethical experimentation.

Table 3: Essential Components for Ethical Research Compliance

| Component | Function | Ethical Principle Served |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | An independent committee that reviews, approves, and monitors research protocols to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects. | Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice [7] [32] |

| Informed Consent Document | A comprehensive written agreement that ensures participants understand the research procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives before agreeing to participate. | Respect for Persons [7] [3] |

| Belmont Report Principles | The three ethical pillars (Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice) that provide the philosophical justification for all federal human subjects regulations. | Foundational Ethical Framework [32] [3] |

| Federal Wide Assurance (FWA) | A binding commitment from an institution to the U.S. government that it will comply with federal regulations for the protection of human subjects. | Systemic Accountability [33] |

| Protocol Risk-Benefit Assessment | A rigorous analysis conducted by the researcher and reviewed by the IRB to ensure that risks to subjects are minimized and are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits. | Beneficence [3] |

Experimental Protocol: A Methodology for Ethical Research Oversight

The following section outlines the standard operational protocol for the ethical review and conduct of human subjects research, as institutionalized by the National Research Act. This methodology is designed to systematically integrate ethical safeguards into every stage of the research lifecycle.

Protocol Development and Submission

The researcher prepares a detailed research protocol. This document must comprehensively describe the study's objectives, methodology, participant population, recruitment procedures, data collection methods, and statistical analysis plans. Crucially, the protocol must include a full section on the protection of human subjects, which details how informed consent will be obtained, how confidentiality will be maintained, and a thorough analysis of potential risks and benefits [32] [3]. This complete submission package is then presented to the registered IRB for review.

IRB Review and Approval Process

The IRB, composed of at least five members with varying backgrounds, including scientific and non-scientific expertise, conducts a formal review of the submitted protocol [32]. The review assesses the study's compliance with ethical principles, focusing on:

- Informed Consent Scrutiny: The IRB verifies that the consent form contains all necessary elements, is written in language understandable to the participant population, and does not include any exculpatory language [3].

- Risk/Benefit Evaluation: The board determines that risks to subjects are minimized and are reasonable in relation to the knowledge gained. The possibility of long-range physical or psychological harm is considered [32] [3].

- Equitable Subject Selection: The IRB assesses the justification for the proposed participant population to ensure that vulnerable groups are not targeted for convenience and that the burdens of research are shared fairly [3]. The IRB can approve, require modifications to, or disapprove the research.

Informed Consent Execution

Once approved, the researcher obtains informed consent from each prospective participant. This process is not merely the signing of a form but a dynamic, ongoing interaction. It involves a discussion that ensures the participant comprehends the study's purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives, and that their participation is entirely voluntary and can be terminated at any time without penalty [3]. For research involving vulnerable populations, additional protections, such as assent from children and permission from parents, are required.

Ongoing Monitoring and Documentation

Following initial approval, the IRB conducts continuing review of the research at intervals appropriate to the level of risk, but at least annually [32]. The researcher is required to submit progress reports and promptly report any adverse events or proposed changes to the protocol. The IRB may conduct audits or inspections to ensure ongoing compliance with the approved plan. Meticulous documentation of the consent process, IRB communications, and all research data is maintained for federal audit and potential future review.

Fifty years after its enactment, the legacy of the National Research Act is profound. It successfully established a permanent infrastructure for research ethics, centering the principles of The Belmont Report and the IRB review process as the cornerstones of human subject protection in the United States [32]. However, contemporary scientific advancements present new challenges that test the boundaries of the original regulatory framework. The rise of artificial intelligence, genomic data banks, and multistate clinical trials has revealed substantive gaps, such as the Common Rule's exclusion of de-identified information and biospecimens from protection, despite modern technology's ability to re-identify individuals [32]. Furthermore, the regulatory system's primary application only to federally funded research creates a patchwork of protections that may not cover all research volunteers [32]. As noted by bioethics scholars, there is a growing need for a standing national bioethics body to address these emerging issues and for continued efforts to assess and improve the quality of IRB reviews [32]. The National Research Act, born from a dark chapter in American medical history, remains a living document, requiring continual reflection and adaptation to ensure it fulfills its enduring mandate: to safeguard the dignity, rights, and welfare of every person who contributes to the advancement of science.

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service between 1932 and 1972, represents a profound failure in research ethics that directly catalyzed the creation of the Belmont Report [4] [14]. This study involved 600 African American men—399 with syphilis and 201 without—who were deliberately deceived about their condition and left untreated even after penicillin became the standard of care in the 1940s [4] [14]. Researchers did not collect informed consent, actively prevented participants from accessing treatment, and deceived them with placebo treatments such as vitamin tonics and aspirin [4] [14]. The study continued for four decades until public exposure in 1972 sparked outrage and led to its termination [4].

In response to the Tuskegee revelation and other ethical breaches, the National Research Act of 1974 established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [34] [35]. This commission spent four years developing ethical guidelines, resulting in the 1979 publication of the Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research [36] [34] [37]. The report provided the ethical foundation for modern human subjects regulations in the United States, creating what some have characterized as "a system like the Bill of Rights for research participants" [35]. This whitepaper deconstructs the Belmont Report's principles and applications, examining their direct relationship to addressing the ethical failures exemplified by Tuskegee and their ongoing relevance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Ethical Principles: Foundation and Tuskegee Violations

The Belmont Report establishes three fundamental ethical principles for human subjects research: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [36] [37] [35]. Each principle directly addresses specific ethical violations uncovered in the Tuskegee study.

Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two ethical convictions: individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [36] [37]. This principle acknowledges the moral requirement to respect individuals' self-determination and to provide additional safeguards for those with limited autonomy [36].

In the Tuskegee study, this principle was egregiously violated through multiple mechanisms. Researchers deliberately deceived participants about their condition and the nature of the study, telling them they were being treated for "bad blood" rather than syphilis [4] [14]. They did not collect informed consent, and actively manipulated participants into procedures by misrepresenting their purpose—for instance, describing lumbar punctures as "special treatment" or "spinal shots" rather than diagnostic procedures [14]. The researchers also exploited the participants' socioeconomic vulnerabilities, offering inducements such as burial insurance that they knew would be particularly compelling for this population [14].

Beneficence

The principle of Beneficence describes an obligation to protect subjects from harm by maximizing possible benefits and minimizing possible harms [36] [35]. This principle is expressed through two complementary rules: "do not harm" and "maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms" [36]. It requires researchers to systematically assess risks and benefits and to ensure that risks are justified by potential benefits [36] [37].

The Tuskegee study violated this principle fundamentally by deliberately withholding effective treatment even after penicillin became widely available and was established as the standard of care for syphilis [4] [14]. Researchers actively prevented participants from accessing treatment by instructing local physicians not to treat them and by intervening with military authorities to prevent treatment of drafted participants [14]. By 1969, at least 28 and perhaps as many as 100 men had died as a direct result of syphilis, yet the study continued [14]. The researchers prioritized their scientific goals over the well-being of their subjects, directly contradicting the ethical obligation of beneficence.

Justice