A Comprehensive Guide to Obtaining Valid Informed Consent in Clinical Trials: Principles, Procedures, and Best Practices

This article provides a complete framework for researchers and clinical trial professionals to ethically and effectively obtain valid informed consent.

A Comprehensive Guide to Obtaining Valid Informed Consent in Clinical Trials: Principles, Procedures, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for researchers and clinical trial professionals to ethically and effectively obtain valid informed consent. Covering foundational ethical principles, step-by-step methodological application, solutions for complex scenarios including vulnerable populations, and processes for regulatory validation, this guide synthesizes current regulations and health literacy best practices to ensure participant autonomy and data integrity.

The Ethical and Regulatory Bedrock of Informed Consent

Informed consent serves as a cornerstone of ethical clinical research, representing a fundamental shift from paternalistic practices to respect for participant autonomy. Historically, the concept emerged from landmark legal cases and responses to unethical medical experiments, establishing the principle that patients must agree to medical procedures and research interventions [1]. In our modern ethical conception, informed consent is defined as a process by which "a subject voluntarily confirms his or her willingness to participate in a particular trial, after having been informed of all aspects of the trial that are relevant to the subject's decision to participate" [2]. This definition underscores the dual nature of informed consent as both an ethical imperative and a communicative process.

Contemporary understanding positions informed consent at the intersection of accurate factual information and effective communication [3]. This framework recognizes that merely providing information is insufficient; how that information is conveyed, understood, and processed by potential participants is equally critical. The process begins the moment researchers start soliciting participants and continues until no further use is made of the participant's information or biospecimens [4]. This ongoing nature distinguishes true informed consent from the simplistic act of signing a form, which merely documents the process at one point in time.

Essential Elements: Information and Communication Components

Core Informational Elements

The informational components of informed consent must provide comprehensive details enabling an autonomous decision. Based on regulatory requirements and ethical guidelines, these essential elements include [3] [5]:

- Purpose and Nature: A clear statement that the study involves research, description of the research purpose, expected duration of participation, and study procedures

- Risks and Benefits: Description of any reasonably foreseeable risks, discomforts, and potential benefits to participants or others

- Alternatives and Voluntariness: Disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, and a clear statement that participation is voluntary

- Protections and Contacts: Information about confidentiality protections, compensation for injury, contacts for questions about research and participant rights, and the conditions under which participation may be terminated

The following table summarizes the quantitative findings from studies evaluating how these elements are typically addressed in consent processes:

Table 1: Quantitative Evaluation of Informed Consent Processes

| Evaluation Aspect | Finding | Source/Study |

|---|---|---|

| Documentation of 4 core elements (nature, risks, benefits, alternatives) | Documented only 26.4% of the time on consent forms | Bottrell et al. as cited in [1] |

| Participant satisfaction with consent process | Majority "positive" about their experience (169 participants surveyed) | Study in Trials Journal [6] |

| Research staff confidence in facilitating consent | 74.4% felt "very confident" or "confident" | Same survey of 115 staff [6] |

| Staff concerns about participant understanding | 56% expressed concern about whether participants understood complex information | Same survey [6] |

| Phase I consent quantitative assessment | ~80% of patients received complete information about drug characteristics and treatment modalities | Study of 32 taped conversations [7] |

Essential Communication Elements

Effective communication transcends mere information disclosure. The quality of the interaction significantly influences participant understanding and autonomy. Based on communication models adapted to clinical research, essential communication elements include [3]:

- Building Rapport: Establishing trust and equality in the researcher-participant exchange

- Assessing Understanding: Actively checking for comprehension through techniques like "playback" where participants repeat details in their own words

- Using Accessible Language: Avoiding medical jargon, using easy-to-understand language appropriate to the population

- Encouraging Questions: Creating an environment where participants feel comfortable seeking clarification

- Emotional Responsiveness: Recognizing and addressing indirectly expressed anxieties and emotional concerns

Research evaluating the qualitative aspects of consent discussions has revealed specific patterns in communication effectiveness:

Table 2: Qualitative Assessment of Communication Dimensions in Informed Consent

| Communication Dimension | Performance Assessment | Identified Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Information Dimension | Most items scored ≥3.5 (5-point scale) | Assessment of patient understanding scored <3 in 53% of consultations [7] |

| Emotional Dimension | All items scored >3.5 | Generally well-handled by clinicians [7] |

| Interactive Dimension | Lowest mean scores recorded | Difficulty recognizing indirectly expressed anxieties [7] |

| Overall Successful Consultation | 71% of consultations had all three dimensions scoring >3 and balancing one another | Meerwein's model applied to 32 conversations [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Assessment Methodologies

The Process and Quality of Informed Consent (P-QIC) Tool

The P-QIC instrument was developed specifically to quantitatively measure the quality of informed consent encounters through direct observation. The methodology for developing and validating this tool involved [3]:

Instrument Development Protocol:

- Initial Source: Adapted from an observer checklist developed by the Institutional Review Board at Columbia University Medical Center consisting of 25 items

- Theoretical Framework: Based on the model positioning informed consent at the intersection of factual information and effective communication

- Information Elements: Derived from CIOMS guidelines and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Regulation Title 45

- Communication Elements: Derived from the Kalamazoo Consensus Statement, the Conversation Model of Informed Consent, and Delphi consensus-building methods

Psychometric Testing Protocol:

- Sample: 63 students enrolled in health-related programs participated in psychometric testing; 16 students participated in test-retest reliability; 5 investigator-participant dyads were observed for actual consent encounters

- Stimuli Development: Professionally filmed, simulated consent encounters designed to vary in process and quality

- Testing Procedure: Participants watched and rated videotaped simulations of four consent encounters intentionally varied in process and content

- Reliability Assessment: Test-retest reliability established by raters watching videotaped simulations twice; inter-rater reliability demonstrated by two simultaneous but independent raters observing actual consent encounters

- Setting: Conducted at a major urban teaching hospital in the northeastern United States

Validation Outcomes:

- The initial testing demonstrated reliable and valid psychometric properties in both simulated standardized consent encounters and actual consent encounters in hospital settings

- The tool provides a quick assessment of areas of strength and those needing improvement in consent encounters

- Applications include training new investigators and ongoing quality improvement programs for informed consent

Teach-Back and Comprehension Assessment Protocols

The teach-back method is a critical evidence-based technique for assessing and enhancing participant understanding during consent discussions. The protocol involves [1]:

Implementation Steps:

- Explanation: The researcher explains a concept using plain language

- Assessment Request: The researcher asks the participant to explain the concept in their own words

- Clarification: If the participant demonstrates misunderstanding, the researcher re-explains using alternative wording

- Reassessment: The participant again attempts to explain the concept

- Repetition: This cycle continues until understanding is verified

Effectiveness Data:

- Studies implementing health literacy-based consent forms combined with teach-back techniques demonstrated improved patient-provider communication

- Participants reported increased comfort in asking questions when teach-back was employed

- The method helps both patients and clinicians concentrate on essential aspects of the information

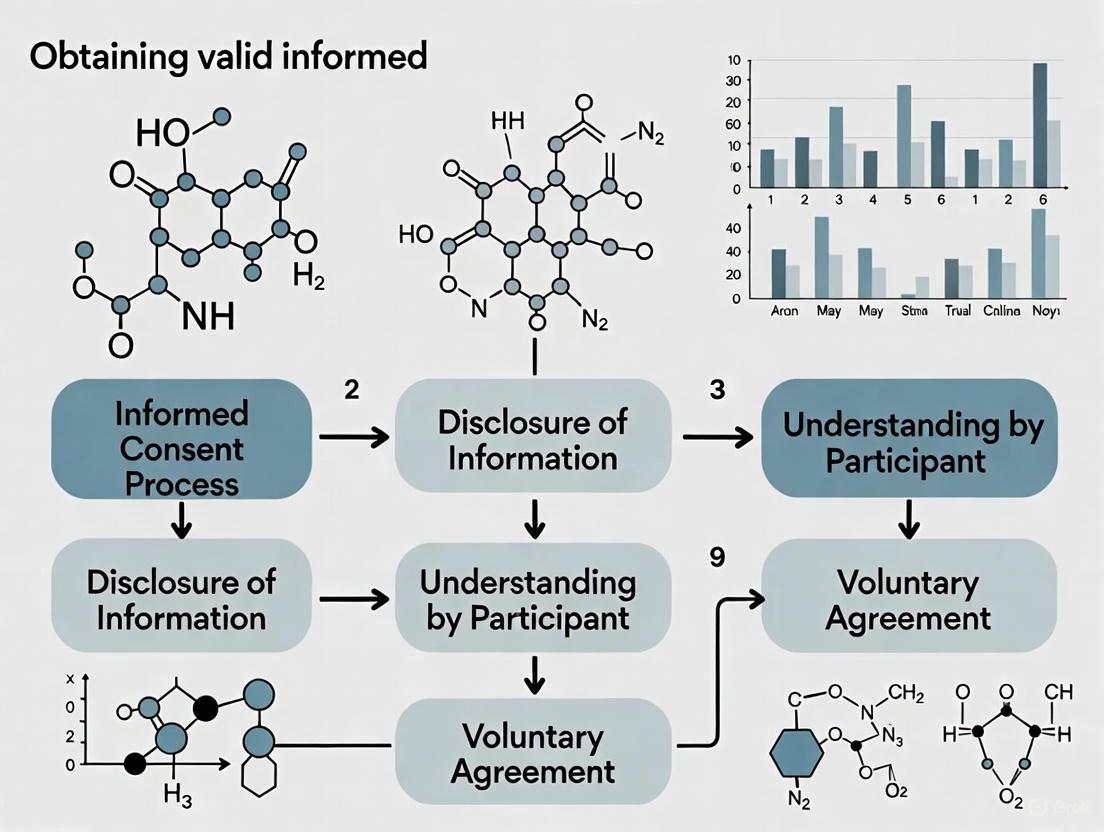

Visualizing the Informed Consent Process

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive nature of informed consent as an ongoing process rather than a single event:

Informed Consent as an Ongoing Process

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Informed Consent Processes

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| P-QIC Instrument | Observational tool measuring process and quality of consent encounters | Training new investigators; quality improvement programs; research on consent effectiveness [3] |

| Teach-Back Method | Verification of participant understanding through playback technique | During consent discussions; assessing comprehension of complex concepts; health literacy adaptation [1] |

| Health Literacy Assessment | Evaluation of readability and comprehension level of consent materials | During consent form development; plain language adaptation; regulatory compliance [4] |

| Essential Elements Checklist | Verification that all required informational components are included | Protocol development; IRB/ethics committee submissions; regulatory compliance [3] [5] |

| Vulnerable Population Protocols | Specialized procedures for participants with diminished autonomy | Research with children, cognitively impaired, prisoners, emergency settings [2] |

Implementation Framework and Procedural Protocols

Structured Consent Discussion Protocol

Based on analysis of successful consent consultations, the following structured protocol is recommended for implementing valid consent processes:

Pre-Consent Preparation Phase:

- Timing and Setting: Schedule dedicated time in a quiet, private setting without interruptions [1]

- Participant Preparation: Provide consent forms in advance, allowing sufficient time for review and consultation with family or advisors [6]

- Support Persons: Encourage participants to bring family members or friends to the discussion when appropriate [6]

- Staff Training: Ensure research staff receive specific training on facilitating informed consent discussions [6]

Consent Discussion Execution:

- Introduction and Rapport: Begin by establishing trust and emphasizing the voluntary nature of participation [3]

- Key Information First: Present a concise and focused presentation of key information most relevant to the participation decision [4]

- Staged Information Delivery: Divide complex information into manageable segments with pauses for questions [7]

- Comprehension Verification: Systematically employ teach-back techniques after explaining critical concepts [1]

- Emotional Awareness: Monitor for indirect expressions of anxiety and address them explicitly [7]

- Documentation: After ensuring understanding, document the consent with appropriate signatures [5]

Post-Consent Continuation:

- Ongoing Availability: Maintain availability for questions throughout the study period [4]

- Reconsent Procedures: Implement procedures for reconsent if new information emerges or study parameters change [1]

- Results Communication: Provide study results to participants in an accessible format after study completion [6]

Special Circumstances Protocol

Vulnerable Populations Adaptation: Research with vulnerable populations requires additional safeguards and adapted procedures [2]:

- Cognitive Impairment: Assess decision-making capacity using standardized tools; involve legally authorized representatives with continued assent from participants when possible

- Emergency Settings: Follow exception from informed consent (EFIC) regulations for emergency research; implement community consultation and public disclosure requirements

- Children: Obtain parental permission with age-appropriate assent from children; tailor information to developmental level

- Language Barriers: Use certified medical interpreters rather than family members; translate consent materials and certify translation accuracy

Waiver of Consent Conditions: Under strict conditions, research without consent may be permissible when [2]:

- Impracticability: Obtaining consent is not feasible due to time, resource, or validity constraints

- Self-Respect: The research does not infringe the principle of self-determination

- Clinical Relevance: The research provides significant clinical relevance justifying the waiver

Valid informed consent represents a sophisticated integration of comprehensive information, effective communication, and ongoing participant engagement. Moving beyond the signed form as an isolated event to conceptualize consent as a dynamic process requires researchers to develop both knowledge and skills in information delivery, interpersonal communication, and comprehension assessment. The experimental protocols and assessment tools detailed in this application note provide evidence-based methodologies for implementing this process-oriented approach. By adopting these structured protocols and utilizing the included researcher toolkit, clinical trial professionals can enhance participant understanding, respect autonomy, and strengthen the ethical foundation of human subjects research.

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing the three core ethical principles of informed consent—voluntariness, information disclosure, and comprehension—in clinical trial research. These principles form the ethical foundation required by international regulations including ICH-GCP, the Declaration of Helsinki, and U.S. FDA guidelines [8] [9]. Robust implementation is critical for protecting participant autonomy, ensuring regulatory compliance, and maintaining the integrity of research data. This guide outlines standardized methodologies for translating ethical theory into verifiable practice, complete with quantitative assessment tools and procedural workflows designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Informed consent is a foundational ethical and legal requirement in clinical research, transforming the participant from a passive subject into an autonomous partner [8] [9]. Its validity rests not on the mere signing of a form but on the successful implementation of a continuous process built on three core principles: information disclosure, comprehension, and voluntariness [9] [10]. These principles are operationalized through the Informed Consent Form (ICF), a document that must balance regulatory completeness with participant understanding [8].

The historical evolution of informed consent, driven by past abuses such as the Nazi experiments and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, underscores its non-negotiable status in modern research [8]. Contemporary regulations, including ICH-GCP E6(R2) and 21 CFR Part 50, enshrine these principles into law, requiring documented evidence that consent was obtained ethically and validly [8] [11]. This document provides the practical framework for meeting these stringent requirements, ensuring that participant welfare and autonomy remain at the center of clinical research.

Quantitative Data on Informed Consent Practices

Empirical studies highlight significant challenges in the practical application of informed consent principles. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings on compliance and readability, which inform the protocols in subsequent sections.

Table 1: Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Compliance of Informed Consent Forms (ICFs) in a Multicenter Analysis [12]

| GCP-Mandated Information Item | Industry Sponsored Studies (% Compliance) | Non-Sponsored Studies (% Compliance) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose of the study | >90% | <50% |

| Risks or discomforts | >90% | <50% |

| Benefits | >90% | <50% |

| Voluntary participation & right to withdraw | >90% | <50% |

| Randomization probability | >90% | <50% |

| Investigator contact information | >90% | <50% |

| Subject rights and responsibilities | 33% | 16% |

| Anticipated out-of-pocket expenses | 24% | <20% |

| Overall GCP Compliance | 79.5% | 55.8% |

Table 2: Readability Analysis of Informed Consent Forms Using Flesch-Kincaid Scale [12]

| Readability Metric | Industry Sponsored Studies (Mean ± SD) | Non-Sponsored Studies (Mean ± SD) | Target Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reading Ease Score | 48.9 ± 4.8 | 38.5 ± 8.0 | >60 [12] [10] |

| Grade Level Score | 9.7 ± 0.7 | 12.2 ± 1.3 | ~8th Grade [10] |

| Categorization (based on Reading Ease) | 51% Difficult, 49% Fairly Difficult | 83% Difficult, 17% Very Confusing | "Standard" or "Fairly Easy" |

Application Notes & Protocols for Core Principles

Principle 1: Information Disclosure

3.1.1 Protocol for Comprehensive Information Disclosure

The goal of this protocol is to ensure all regulatory-required information is completely and accurately disclosed to the prospective participant.

- Step 1: Develop the ICF Draft. Using the current study protocol and Investigator's Brochure, create the ICF. It must include all basic elements stipulated by relevant regulations (e.g., FDA 21 CFR 50.25, ICH-GCP) [10].

- Step 2: Integrate Additional and Specific Elements. Append any additional elements required by the IRB or applicable due to the study's nature. These may include statements on:

- Unforeseeable risks.

- Circumstances for investigator-terminated participation.

- Additional costs to the participant.

- Consequences of withdrawal.

- Disclosure of significant new findings [10].

- Step 3: Cross-Reference and Validate Content. Systematically cross-reference the ICF with the study protocol to ensure all procedures, visits, and experimental interventions are accurately described. Verify that all risks listed in the Investigator's Brochure are included in the ICF's "Risks" section [10].

- Step 4: IRB/EC Submission and Revision. Submit the draft ICF and study protocol to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee (EC) for review. Incorporate all feedback and secure final approval before any participant is consented [8] [11].

3.1.2 The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents for Information Disclosure

| Essential Material | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Approved Study Protocol & Investigator's Brochure | Serves as the source of truth for all study procedures, risks, and investigational product details to be disclosed [10]. |

| Regulatory Checklist (e.g., 21 CFR 50.25 Checklist) | Ensures every mandated basic and additional element of informed consent is included in the ICF draft [10]. |

| IRB/EC Application Package | Formalizes the ethical review process, providing the committee with all necessary documents to assess the adequacy of subject protection [8]. |

Principle 2: Comprehension

3.2.1 Protocol for Assessing and Ensuring Participant Comprehension

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to verify that the disclosed information is understood by the participant, moving beyond mere document delivery to an interactive process.

- Step 1: Pre-Consent Readability Assessment. Before IRB submission, assess the ICF's readability using a validated tool like the Flesch-Kincaid scale. The target is a Reading Ease score >60 and a Grade Level of 8th grade or lower [12] [10]. Use plain language and avoid technical jargon.

- Step 2: The Interactive Consent Discussion. The investigator or a qualified designee must conduct a structured discussion with the potential participant. This is not a passive reading exercise but a two-way dialogue [9].

- Step 3: Comprehension Verification via Teach-Back Method. After explaining a key concept (e.g., randomization, risks, right to withdraw), ask the participant to explain it back in their own words [9]. Document the participant's questions and the investigator's answers. This step is critical for validating understanding.

- Step 4: Assessment and Documentation. Use open-ended questions to gauge understanding (e.g., "Can you tell me what might happen if you decide to leave the study early?"). The investigator must make a professional judgment that the participant has understood the information before proceeding to signature [11]. Document the process, including the use of any translated materials or interpreters.

The following workflow diagrams the comprehensive comprehension verification process.

Principle 3: Voluntariness

3.3.1 Protocol for Ensuring Voluntary Decision-Making

This protocol is designed to create an environment free of coercion and undue influence, allowing for a choice made purely of the participant's own free will.

- Step 1: Environment Setup. Conduct the consent discussion in a private setting, free from distractions and outside pressure. The participant should be given adequate time to consider the information [9] [13].

- Step 2: Explicit Verbal and Written Statements. The investigator must explicitly state, both verbally and within the ICF, that:

- Step 3: Mitigate Perceived Coercion. For participants with whom the investigator has a pre-existing relationship (e.g., patient-physician), explicitly address that their clinical care will not be affected by their decision. Avoid any language that could be perceived as persuasive or incentivizing beyond the disclosed benefits [9].

- Step 4: Facilitate Unpressured Deliberation. Actively encourage the participant to discuss the study with family, friends, or independent advisors. Avoid rushing the decision. For vulnerable populations, ensure additional safeguards are in place, such as the involvement of a neutral third party or legally authorized representative [9] [11].

The logical relationship between environmental factors, investigator actions, and the outcome of a voluntary decision is shown below.

Integrated Workflow and Advanced Considerations

The following diagram synthesizes the protocols for all three principles into a single, integrated workflow for obtaining valid informed consent.

Table 3: Protocol for Special Population Considerations

| Participant Population | Core Consideration | Protocol Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Non-English Speakers | Linguistic comprehension | Use IRB-approved translated ICFs. For unforeseen scenarios, use a short-form consent with an interpreter and a written summary [10]. |

| Minors (Children) | Legal consent & developmental understanding | Obtain permission from parent/guardian. Obtain assent from the child using age-appropriate language and documentation (e.g., simplified forms, stickers) [13]. |

| Incapacitated Adults | Legal consent & diminished autonomy | Obtain consent from a Legally Authorized Representative (LAR). The LAR must be qualified, without conflicts of interest, and familiar with the participant's wishes [13]. |

| Adults with Low Literacy | Comprehension | Rely more heavily on the interactive discussion and verbal teach-back methods. An impartial witness may be required to attest that information was fairly presented [13]. |

The protocols outlined in this document provide a actionable roadmap for embedding the core ethical principles of voluntariness, information disclosure, and comprehension into every stage of the informed consent process. By treating consent as a continuous, interactive dialogue rather than a singular administrative task, researchers can fulfill both the letter and the spirit of international regulations. The quantitative data presented reveals clear areas for improvement, particularly in enhancing the readability of ICFs and ensuring consistent GCP compliance across all study types. The rigorous application of these standardized methodologies is the ultimate safeguard for participant autonomy and the cornerstone of ethically sound and legally defensible clinical research.

Obtaining valid informed consent is a fundamental ethical and regulatory requirement in clinical research. This process is governed by robust frameworks designed to protect participant autonomy, safety, and rights. The Common Rule (45 CFR Part 46) in the United States and the International Council for Harmonisation's Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines are two pivotal regulatory systems that set the standard for this process. While the Common Rule provides the foundational federal policy for the ethical conduct of human subjects research, ICH-GCP offers an internationally recognized quality standard that ensures data credibility and participant protection across global trials. This application note details the specific requirements of these frameworks, provides protocols for their implementation, and situates them within the critical practice of securing valid informed consent.

Regulatory Framework Analysis

The Common Rule: Core Principles and Consent Requirements

The Common Rule outlines the basic provisions for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), informed consent, and the protection of human subjects in research. Its provisions for informed consent are both procedural and substantive, mandating that consent must be informed, comprehensible, and voluntary [1].

- Key Elements: The regulations stipulate specific elements that must be included in the informed consent document and process. These include a clear explanation of the research purpose, procedures, foreseeable risks, potential benefits, alternative procedures, and a statement of confidentiality [14] [1].

- Comprehension: A core tenet of the Common Rule is that the information presented to the potential subject must be in a language and at a level of complexity that is understandable to the subject or their legally authorized representative. The process must facilitate the participant's understanding and voluntary decision-making [14].

- Documentation: Informed consent must be documented by a written form that the participant has signed, unless this requirement is specifically waived by the IRB under narrow circumstances, such as when the signed consent form would be the only record linking the subject to the research and a breach of confidentiality would be the primary risk [1].

ICH-GCP Guidelines: A Global Benchmark

The ICH-GCP guidelines provide an international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting trials that involve the participation of human subjects. The principles of ICH-GCP have been adopted by regulatory authorities in the U.S., the European Union, Japan, and many other countries, making it a cornerstone for global drug development [15].

- Participant Protection: The primary focus of ICH-GCP is to ensure that the rights, safety, and well-being of trial subjects are protected and that the clinical trial data are credible [15].

- Informed Consent Process: ICH-GCP emphasizes that informed consent is a process that begins before a subject's participation and continues throughout the trial. The investigator, not a delegate, has a direct responsibility to ensure that this process is conducted properly and that the subject has ample opportunity to ask questions and receive satisfactory answers [16].

- Ongoing Consent: The guidelines underscore that subjects must be informed of any new information that becomes available during the trial which may be relevant to their willingness to continue participation. Re-consent is required when this new information is significant [16].

The forthcoming E6(R3)* update, announced for September 2025, marks a significant evolution of these guidelines. It incorporates more flexible, risk-based approaches and embraces innovations in trial design and technology, while maintaining a strong focus on participant protection and data reliability [15].

Comparative Analysis of Framework Requirements

The table below summarizes and compares the key informed consent requirements as outlined by the Common Rule and ICH-GCP guidelines.

Table 1: Key Informed Consent Requirements in the Common Rule vs. ICH-GCP

| Feature | The Common Rule | ICH-GCP Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Protection of human subjects in research; ethical principles [1] | Credibility of data and protection of participant rights, safety, and well-being [15] |

| Core Consent Elements | Nature of research, risks, benefits, alternatives, confidentiality, voluntary participation, contact information [14] | Detailed trial information, including trial treatment(s), purpose, procedures, allocation of treatment, and compensation [15] |

| Process Emphasis | Ensuring comprehension and voluntariness; information must be understandable [14] [1] | A continuing process, initiated prior to consent; investigator-responsibility for ensuring understanding [16] |

| Documentation | Typically a signed consent form, with specific waivers possible [1] | A signed and dated written consent form prior to participation [16] |

| Ongoing Consent | Implied through the right to withdraw; specific re-consent for protocol changes is an IRB decision | Explicitly required when new relevant information becomes available [16] |

| Key Update (as of 2025) | - | E6(R3): Promotes flexibility, risk-based approaches, and use of technology [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Valid Informed Consent

Protocol 1: The Pre-Consent Preparation and Assessment Workflow

This protocol ensures all foundational work is complete before approaching a potential participant.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Valid Informed Consent

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Consent Process |

|---|---|

| Protocol Summary (Lay Language) | Serves as the foundation for creating an understandable consent form; explains the study's purpose and procedures simply [14]. |

| IRB-Approved Informed Consent Form (ICF) | The legal document that structures the consent discussion and ensures all regulatory elements are addressed [14] [16]. |

| Visual Aids & Multimedia Tools | Enhances comprehension of complex procedures (e.g., randomization, blinding) and helps communicate risks and benefits effectively [1]. |

| Health Literacy Assessment Tool | Aids in screening for potential barriers to understanding, allowing the research team to tailor their communication approach [1]. |

| Teach-Back Method Script | Provides a structured method for assessing participant understanding by asking them to explain the study in their own words [1]. |

Procedure:

- IRB Submission and Approval: Submit the final clinical trial protocol, the informed consent form (ICF), and all participant-facing materials to the IRB or Ethics Committee for review and approval. Do not proceed until written approval is obtained [14].

- Team Training and Delegation: Train all research staff involved in the consent process on the study protocol, the approved ICF, and principles of health literacy. Document this training. The principal investigator retains ultimate responsibility [1].

- Participant Pre-Screening: Identify potential participants who meet the preliminary eligibility criteria for the study. This assessment should be documented in the study records.

- Environment Preparation: Schedule a dedicated meeting in a private, quiet setting free from distractions to conduct the informed consent discussion. Allow for sufficient time (typically 30-60 minutes).

Protocol 2: The Informed Consent Discussion and Documentation Process

This protocol details the step-by-step procedure for conducting and documenting a valid informed consent discussion.

Procedure:

- Initial Introduction and Purpose: Introduce yourself and your role. Clearly state that the conversation is about a research study and distinguish research from standard clinical care [14] [1].

- Presentation of the ICF: Provide the participant with a copy of the IRB-approved ICF. Use the document as a guide for the discussion, but explain the content using simple, everyday language. Avoid or thoroughly define medical jargon [14].

- Systematic Review of Key Elements:

- Nature and Purpose: Explain the research purpose, duration, and procedures. Describe any experimental procedures clearly [14].

- Risks and Discomforts: Discuss all reasonably foreseeable risks (physical, psychological, social, financial) and the steps taken to minimize them [14] [1].

- Benefits: Describe any potential benefits to the participant or to society. Be clear if there is no direct benefit to the participant [14].

- Alternatives: Explain the alternatives to participation, which may include other treatments or no treatment at all [14] [1].

- Confidentiality: Explain how records will be protected, who will have access (including the possibility of regulatory agency review), and how data will be stored and eventually destroyed [14].

- Voluntary Participation: Explicitly state that participation is voluntary and that refusal or withdrawal will not result in penalty or loss of benefits to which the participant is otherwise entitled. Explain the process for withdrawal and any potential consequences of early withdrawal (e.g., need for a safe taper of investigational product) [14] [16].

- Assessment of Understanding (Teach-Back): Use the teach-back method to confirm comprehension. Ask open-ended questions such as, "Can you tell me in your own words what the main risks of this study are?" or "What would you do if you wanted to stop being in the study?" [1].

- Answering Questions: Encourage and answer all questions the participant or their family members may have. Avoid rushing the process and offer the opportunity to take the ICF home and discuss it with family, friends, or their personal physician [14] [16].

- Documentation of Consent: Once all questions are answered and the participant demonstrates understanding, proceed with signing the ICF. The participant and the individual conducting the consent discussion should sign and date the form. The participant receives a copy of the signed document [16].

Protocol 3: Maintaining Valid Consent Throughout the Trial

Informed consent is a continuous process, not a single event. This protocol ensures consent remains valid for the study's duration.

Procedure:

- Ongoing Communication: Maintain regular, open communication with the participant throughout their involvement in the trial. Check in about their well-being and reinforce that they can withdraw at any time without penalty [16].

- Monitoring for New Information: Monitor for any new safety information or significant changes to the protocol that arise during the trial. This includes new risks identified in other study participants or in the scientific literature.

- Re-Consent Process: If new information is deemed relevant to the participant's willingness to continue in the study, prepare an amended ICF and submit it to the IRB for approval. Once approved, schedule a meeting with the participant to discuss the new information and obtain their re-consent using the same rigorous process as the initial consent. Document the re-consent with a new signed ICF [16].

- Documenting Withdrawal: If a participant decides to withdraw, document the date and reason for withdrawal (if provided). Ensure that any procedures for safe termination of participation are followed (e.g., a final safety assessment) [14].

Visualization of the Informed Consent Process

The following diagram illustrates the complete, continuous workflow for obtaining and maintaining valid informed consent, from preparation through trial completion, as detailed in the experimental protocols.

Diagram 1: The Informed Consent Workflow

Discussion

The process of obtaining valid informed consent is a dynamic and multifaceted responsibility for researchers. The regulatory frameworks of the Common Rule and ICH-GCP provide the essential structure, but the application requires critical thinking, cultural competence, and a genuine commitment to participant partnership.

A significant challenge is ensuring true comprehension, not just a signature. The use of validated health literacy tools and the teach-back method are evidence-based strategies to bridge the comprehension gap [1]. Furthermore, the increasing globalization of clinical trials necessitates sensitivity to cultural and linguistic differences. What constitutes voluntary consent in one culture may not in another, and reliance on professional interpreters is non-negotiable for non-native speakers [1] [17].

The future of informed consent is being shaped by technological innovation and regulatory evolution. The ICH E6(R3) guidelines encourage the use of electronic consent (eConsent) platforms, which can incorporate interactive modules, videos, and embedded comprehension checks to enhance understanding [15]. These tools, aligned with a risk-based approach, allow for a more proportional and efficient consent process, focusing greater resources on higher-risk studies while maintaining rigorous ethical standards.

Valid informed consent is the ethical and legal bedrock of clinical research. The Common Rule and ICH-GCP guidelines provide a comprehensive, complementary set of requirements that, when implemented faithfully through detailed protocols, ensure that participants' autonomy is respected and their welfare is protected. As the clinical trial landscape evolves with new technologies and global collaborations, the principles of clear communication, ongoing dialogue, and participant-centered care remain paramount. By adhering to these frameworks and employing robust methodologies, researchers can build the trust necessary for successful and ethical clinical research.

Informed consent is a foundational ethical and regulatory requirement in clinical research. It is a process by which a subject voluntarily confirms their willingness to participate in a particular trial, after having been informed of all aspects of the trial that are relevant to their decision to participate [2]. This process is documented through a written, signed, and dated informed consent form, which serves as evidence that the consent conversation took place and that the participant agreed to join the study [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise elements required in a consent form is critical not only for regulatory compliance but also for ensuring participant autonomy, safety, and understanding. A properly executed informed consent process respects the participant's right to self-determination and establishes the ethical foundation for the entire clinical investigation.

Regulatory Foundation & Core Components

The content of an informed consent form is not arbitrary; it is strictly defined by national and international regulations. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations at 21 CFR 50.25 and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations at 45 CFR 46.116 delineate the basic and additional elements that must be included to make a consent form legally effective [18] [19]. Furthermore, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines provide an international standard, defining informed consent as the process whereby a subject voluntarily confirms his or her willingness to participate after being informed of all relevant trial aspects [2].

The following workflow outlines the structured process of developing and obtaining a legally valid informed consent, from foundational regulations to participant understanding.

The Eight Basic Required Elements

The following table synthesizes the eight basic elements of informed consent as mandated by FDA regulations (21 CFR 50.25(a)), which must be present in every consent form for clinical research [18] [20] [19].

Table 1: Basic Required Elements of a Legally Valid Informed Consent Form

| Element Number | Element Description | Key Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Statement of Research & Procedures: A statement that the study involves research, an explanation of the purposes, expected duration of participation, a description of procedures, and identification of any experimental procedures [18] [19]. | Clearly distinguish research procedures from standard care. Specify the total number of subjects involved [20]. |

| 2 | Description of Foreseeable Risks: A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject [18] [19]. | Include physical, psychological, social, and economic risks. Describe measures to minimize risks [19]. |

| 3 | Description of Potential Benefits: A description of any benefits to the subject or to others that may reasonably be expected from the research [18] [19]. | Avoid unproven claims. Clearly state if there is no direct benefit to the subject [19]. |

| 4 | Disclosure of Alternatives: A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subject [18] [20]. | Identify the subject's alternatives, including the alternative of not receiving therapy [19]. |

| 5 | Statement on Confidentiality: A statement describing the extent to which confidentiality of records will be maintained, noting that the FDA may inspect the records [18] [20]. | Explain who will have access to the data (e.g., sponsor, IRB, FDA) and the steps taken to ensure confidentiality [19]. |

| 6 | Compensation for Injury: For research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation of whether any compensation and medical treatments are available if injury occurs and, if so, what they consist of [18] [20]. | Provide details on how to obtain further information about research-related injury. Note that consent cannot waive a subject's legal rights [20]. |

| 7 | Contacts for Questions: An explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions about the research and research subjects' rights, and whom to contact in the event of a research-related injury [18] [20]. | Provide the names and contact information of the principal investigator and an independent contact (e.g., IRB) [21]. |

| 8 | Voluntary Participation: A statement that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits, and the subject may discontinue participation at any time [18] [20]. | Emphasize that the decision will not affect the quality of medical care received [2] [22]. |

Additional Elements of Informed Consent

Under certain circumstances, one or more additional elements of information must be provided to the subject. The IRB determines which of these elements are appropriate based on the nature of the research and its context [18] [20].

Table 2: Additional Elements of Informed Consent (as required by the IRB)

| Element | Description | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Unforeseeable Risks | A statement that the treatment or procedure may involve risks to the subject (or embryo/fetus) that are currently unforeseeable [18] [20]. | Early-phase trials, novel interventions. |

| Termination by Investigator | Anticipated circumstances under which the subject's participation may be terminated by the investigator without the subject's consent [18] [19]. | Protocol non-compliance, intercurrent illness. |

| Additional Costs | Any additional costs to the subject that may result from participation in the research [18] [19]. | Procedures not covered by the sponsor or insurance. |

| Consequences of Withdrawal | The consequences of a subject's decision to withdraw and procedures for orderly termination [18] [20]. | Long-term follow-up studies, data handling post-withdrawal. |

| Significant New Findings | A statement that significant new findings developed during the research that may relate to the subject's willingness to continue will be provided [18] [20]. | All clinical trials, especially those of long duration. |

| ClinicalTrials.gov Statement | For applicable clinical trials, a statement that a description of the trial will be available on ClinicalTrials.gov [18]. | FDA-regulated clinical trials. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Legally Valid Consent Process

Protocol for Developing and Obtaining Informed Consent

Objective: To ensure every research participant (or their legally authorized representative) provides legally effective, ethically valid, and voluntary informed consent prior to initiating any study-related procedures.

Materials & Reagents:

- Final IRB/EC-approved informed consent document: The definitive version of the consent form, including all required elements.

- Study protocol and Investigator's Brochure: Reference documents to ensure accurate information is conveyed.

- A private, quiet setting: To facilitate an open discussion without coercion or undue influence.

- eConsent platform or paper forms: For documentation, as approved by the IRB/EC [22].

- Certified translation(s): For non-English speaking participants, ensuring the consent form is in a language understandable to the subject [21].

Methodology:

- Preparation and Documentation:

Information Disclosure Process:

- Conduct a structured discussion with the participant/LAR in a setting that minimizes distractions [2].

- Explain the study using lay language, avoiding technical jargon. Address all basic and applicable additional elements from Tables 1 and 2 [19] [21].

- Specifically highlight key information: the purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, alternatives, voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw [2] [22].

- Encourage and answer all questions thoroughly. Use interactive methods like "teach-back" where the participant explains the study in their own words to verify comprehension [21].

Assessment of Understanding and Voluntariness:

Documentation of Consent:

- Provide the participant/LAR with a copy of the signed and dated consent form [2].

- For paper-based consent, ensure the participant and the person obtaining consent sign and date the form simultaneously. For electronic consent (eConsent), use a system that captures electronic signatures and timestamps and provides a copy to the participant [22].

- Document the entire process in the participant's study record, including the date, time, and any questions raised and answered [21].

Ongoing Consent (Re-consent):

- Monitor the study for significant new findings or protocol changes that might affect a participant's willingness to continue.

- If such events occur, obtain re-consent using an IRB/EC-approved revised consent form or consent addendum [22].

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for the Consent Process

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for the Informed Consent Process

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| IRB/EC-Approved ICF | The legally vetted document containing all required elements and information for the participant. |

| Protocol Summary/Visual Aids | Simplified summaries, diagrams, or videos to enhance participant understanding of complex study designs [21]. |

| eConsent Platform | A digital system for presenting consent information, facilitating electronic signatures, and managing version control [22]. |

| Comprehension Assessment Tool | A short questionnaire or a set of verbal questions to objectively verify the participant's understanding of key study aspects [21]. |

| Certified Translation Services | To provide legally accurate translations of the ICF for participants who do not speak the primary study language [21]. |

| Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) Guidelines | Institutional policies and checklists to guide interactions with LARs for subjects unable to consent for themselves [20]. |

Critical Considerations for Valid Implementation

Ensuring Participant Comprehension

The consent form must be written in language that is easily understood by the subjects [2]. This involves using a second-person writing style (e.g., "you" and "we"), explaining technical terms, and avoiding complex legalistic language [19]. The use of multimedia components in eConsent, such as video and audio, can further break down complex information to ensure true understanding [22].

Prohibited Language and Practices

Informed consent forms must never include exculpatory language, which is any language through which the subject is made to waive their legal rights or that releases the investigator, sponsor, or institution from liability for negligence [20] [19]. Furthermore, consent forms should not contain unproven claims of effectiveness or certainty of benefit, as this can be misleading and constitute undue influence [19].

Special Circumstances and Vulnerable Populations

Research involving vulnerable populations—such as children, incapacitated adults, or prisoners—requires additional safeguards [2]. For children, consent must be obtained from a parent or guardian (LAR), and the child's assent should be sought when appropriate [20]. For adults who lack decision-making capacity, consent must be obtained from a legally authorized representative [2] [20]. The IRB provides specific guidance on consent procedures for these populations.

Informed consent serves as a cornerstone of ethical clinical research, yet under specific low-risk circumstances, regulatory frameworks permit exceptions to the standard requirement for individual written consent. The waiver of informed consent represents a critical ethical and methodological consideration for researchers designing pragmatic clinical trials, quality assurance activities, and comparative effectiveness studies [23]. These research approaches aim to embed clinical investigation within routine healthcare practices to generate generalizable evidence relevant to real-world settings.

The fundamental ethical discordance addressed by consent waivers stems from the observation that while rigorous research requires consent for practice evaluation, routine clinical decision-making often lacks similar formal consent processes for equivalent treatments [23]. This ethical framework recognizes that traditional written informed consent models can create significant barriers to research feasibility and inclusiveness, potentially resulting in study populations that differ substantially from broader patient populations in important characteristics such as age, comorbidity burden, and prognosis [23]. For research evaluating interventions that will affect all patients within a system, waiver of consent models may minimize selection bias and enhance generalizability.

Regulatory Framework and Ethical Justification

International and National Guidelines

Global research organizations have established specific guidelines governing the circumstances under which waiver of consent may be ethically permissible. Our analysis identifies key regulatory frameworks across international and national jurisdictions, summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: International and National Guidelines for Waiver of Consent in Clinical Research

| Governing Organization | Guideline Name | Year | Key Waiver Provisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) | International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans | 2016 | Guideline 10 addresses waiver of consent for health-related research, identifiable data/biological specimens, non-identifiable data, and research involving vulnerable populations [23] |

| US Department of Health & Human Services | Code of Federal Regulations (The Common Rule) | 2019 | IRB waiver or alteration permitted for clinical investigations involving no more than minimal risk [23] |

| Canadian Institutes of Health Research | Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans | 2018 | Articles 3.7A and 3.7B outline waiver conditions for various research types including social sciences and public health research [23] |

| European Parliament and Council | Regulation No 536/2014 On Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use | 2014 | Paragraph 33 and Article 30 specifically address cluster randomized trials where groups rather than individuals are allocated to interventions [23] |

| National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) | National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research | 2018 | Chapter 2.3.10 addresses research using personal information or personal health information [23] |

Ethical Principles and Justification

The ethical justification for waiving informed consent rests on several interconnected principles. Low-risk pragmatic clinical research, such as learning health system research and comparative effectiveness studies, aims to evaluate interventions in real-world settings, often comparing medical treatments already in common use [23]. When the risks inherent in research participation approximate those encountered in routine clinical care, the requirement for individual consent may be ethically modified.

The increasing recognition of healthcare services' impact on clinical outcomes, coupled with digital advancements facilitating previously impossible research, has stimulated interest in appropriate utilization of consent waivers in minimal-risk clinical research [23]. The waiver of consent is particularly relevant for comparative effectiveness studies and health-service interventions designed to affect broad patient populations, where traditional consent models would limit generalizability and introduce selection bias.

Table 2: Core Ethical Criteria for Waiver of Consent

| Criterion | Ethical Rationale | Application in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Risk | Research risks do not exceed those encountered in routine clinical care | Protects participants from harm while facilitating research in real-world settings [23] |

| Practical Impracticability | Obtaining consent would make the research impossible or methodologically invalid | Preserves scientific validity when researching system-level interventions or including representative populations [23] |

| Respect for Persons | Notification processes maintain acknowledgment of participant dignity | Provides information about research participation even when formal consent is waived [24] |

| Social Value | Research addresses important questions that could not be answered without waiver | Ensures that risks to autonomy are proportionate to potential knowledge gains [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Implementing Consent Waivers

Protocol 1: Ethics Review and Approval Process

Objective: To establish a standardized procedure for obtaining institutional review board (IRB) or research ethics committee (REC) approval for waiver of consent in eligible clinical studies.

Materials and Reagents:

- IRB/REC application forms

- Study protocol document

- Risk assessment matrix

- Data management plan

- Participant information materials (for notification when applicable)

Procedure:

- Study Design Phase: Determine whether the research qualifies as minimal risk according to regulatory definitions. Document how risks are not greater than those encountered in routine clinical care [23].

- Feasibility Assessment: Evaluate whether obtaining individual consent would be impracticable due to methodological requirements (e.g., cluster randomization, need for representative population) [23].

- Protocol Documentation: Explicitly describe in the study protocol the justification for consent waiver, including how the research meets regulatory criteria.

- Ethics Submission: Submit complete application to the relevant IRB/REC, highlighting how the research satisfies the following criteria:

- Research involves no more than minimal risk to participants

- Waiver will not adversely affect participant rights and welfare

- Research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver

- Whenever appropriate, participants will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation [23]

- Committee Engagement: Be prepared to address committee questions regarding risk categorization and alternative consent approaches.

- Approval Documentation: Obtain and file formal approval of the consent waiver before initiating any research procedures.

Protocol 2: Participant Notification Procedures

Objective: To implement ethical participant notification processes for studies conducted under waiver of consent, promoting respect for persons and maintaining trust in research institutions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Notification templates (letters, emails, posters)

- Contact information for eligible participants

- Educational materials about the research

- Procedures for addressing participant inquiries

- Opt-out mechanisms (when applicable)

Procedure:

- Notification Design:

- Develop participant-friendly notification materials explaining the research purpose, procedures, and data usage

- Tailor communication methods to the specific population and healthcare context

- Include information about participant rights and contact information for questions [24]

Implementation Strategy:

- Deploy multi-modal notification approaches (e.g., letters, emails, waiting room posters, clinician conversations)

- Sequence notifications to maximize reach while minimizing burden

- For cluster randomized trials, consider presentations at staff meetings and institutional communications [24]

Content Optimization:

- Determine the appropriate amount of information to disclose, ranging from general statements about institutional research to detailed study information

- Balance comprehensiveness with accessibility and readability

- Include information about how to opt out of data use when feasible [24]

Response Management:

- Establish procedures for addressing participant questions and concerns

- Train staff to respond appropriately to inquiries

- Document and address participant objections promptly

Effectiveness Evaluation:

- Monitor reach of notification efforts

- Solicit feedback on notification clarity and comprehensiveness

- Adjust approaches based on participant and stakeholder input

Visualization of Waiver Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for determining when a waiver of informed consent may be appropriate for a clinical study:

Waiver of Consent Decision Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Implementing Consent Waiver Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IRB/REC Application Templates | Standardized documentation for ethics review | Pre-formatted templates specific to waiver requests improve review efficiency and compliance [23] |

| Risk Assessment Matrix | Systematic evaluation of study risks | Visual tool comparing research risks to routine clinical care risks; supports minimal risk determination [23] |

| Participant Notification Materials | Communication of research information | Letters, emails, posters, and educational materials tailored to participant literacy and accessibility needs [24] |

| Data Protection Protocols | Safeguarding of participant data | Encryption, anonymization, and access control measures for research with waived consent [23] |

| Accessibility Resources | Support for diverse participant needs | Adapted materials for participants with communication, hearing, or visual disabilities [25] |

| Opt-Out Mechanism Framework | Respect for participant autonomy | Structured processes allowing participants to exclude their data from research when feasible [24] |

The waiver of informed consent represents a carefully circumscribed exception within clinical research ethics, reserved for specific minimal-risk situations where traditional consent processes would compromise study feasibility or validity. International guidelines demonstrate broad consensus on the core principles governing such waivers, emphasizing minimal risk, practicability, and protection of participant rights [23].

When implemented appropriately with proper ethical oversight, waiver of consent enables important research on healthcare delivery and comparative effectiveness that would otherwise be impossible, ultimately strengthening the evidence base for routine clinical care. Even when formal consent is waived, researchers should default to providing participants with information about the research [24], thereby respecting the ethical principle of respect for persons and maintaining trust in the research enterprise.

This protocol provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a structured framework for evaluating and implementing consent waivers when scientifically and ethically justified, advancing the goal of a learning health system while maintaining rigorous ethical standards.

Executing the Consent Process: A Step-by-Step Operational Blueprint

Within the framework of obtaining valid informed consent in clinical trials, the creation of a comprehensible consent document is not merely an administrative task—it is an ethical imperative. The informed consent form (ICF) serves as the foundational record of the participant's agreement and a reference source throughout the study. Its effectiveness hinges on the participant's ability to read, understand, and reflect upon its content. Regulatory bodies, including the FDA, and ethical principles outlined in the Belmont Report, emphasize that true informed consent depends on comprehension, which is severely compromised if the document is written in complex, technical language [10] [26]. This document outlines the application notes and protocols for developing ICFs that adhere to the recommended 8th-grade reading level, thereby fostering valid informed consent.

The Rationale for Plain Language and Readability

The transition towards participant-centric clinical research has solidified the role of clear communication as a cornerstone of ethical practice.

- Ethical Foundations: The Belmont Report's principle of Respect for Persons requires that subjects be given the opportunity to choose what will or will not happen to them. This autonomy is meaningless if the information provided to facilitate choice is incomprehensible [10].

- Comprehension Gap: Empirical evidence consistently reveals a significant gap between the intended meaning of ICFs and participant understanding. A 2021 survey of research staff found that 56% were concerned about whether participants had understood complex information [27]. Studies evaluating readability have demonstrated that many consent forms are written at a grade level of 10-11 or higher, far exceeding the recommended 8th-grade level and the average reading ability of the public [26] [28].

- Regulatory Guidance: U.S. regulatory agencies explicitly recommend that written ICFs contain "easy-to-read and understandable information so a lay person can make an informed decision about participating in a study" [10]. The Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB, for instance, recommends the ICF reading level be no higher than 8th grade [29].

Quantitative Readability Assessments

To ensure compliance with readability standards, objective metrics should be employed. The following table summarizes the common readability indices and their target values for ICFs.

Table 1: Readability Indices for Informed Consent Form Assessment

| Index | Target for ICFs | Interpretation of Scores | Formula Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flesch Reading Ease (FRES) | 60-70 (Standard) or higher [30] | Scores 0-29: Very Confusing; 30-49: Difficult; 50-59: Fairly Difficult; 60-69: Standard; 70-79: Fairly Easy [30] | Word length and sentence length [26] |

| Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level | ≤ 8th Grade [29] | Translates the FRES into a U.S. school grade level (e.g., 8.0 = 8th grade) [26] | Word length and sentence length [26] |

| Gunning Fog Index | 7 or 8 [26] | The result indicates the years of formal education needed to understand the text on first reading. A score above 12 is too hard for most readers. [26] | Sentence length and complex words (3+ syllables) [26] |

Experimental Protocol: Readability Analysis

Purpose: To objectively determine the reading grade level of a draft informed consent document. Methodology:

- Document Preparation: Compile the complete text of the ICF in a word processing software like Microsoft Word. Omit headers, footers, and page numbers for analysis.

- Software Configuration:

- In Microsoft Word, navigate to: File > Options > Proofing.

- Under "When correcting spelling and grammar in Word," ensure "Check grammar with spelling" is selected.

- Select the "Show readability statistics" check box [29].

- Analysis Execution: Run a full spelling and grammar check on the document. Upon completion, a Readability Statistics dialog box will appear.

- Data Recording: Record the Flesch Reading Ease score and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level.

- Interpretation: Compare the obtained scores to the targets in Table 1. If the grade level exceeds 8.0, iterative revisions are required.

A Protocol for Drafting and Simplifying Consent Documents

Achieving an 8th-grade reading level requires a systematic approach to writing. The following workflow and detailed tips provide a concrete protocol for researchers.

Diagram 1: ICF Plain Language Development Workflow. This diagram outlines the iterative process of drafting, revising, and validating an informed consent form for readability.

Application Notes for Plain Language:

Word Choice:

- Use common, short words (≤ 3 syllables) [29] [30]. For example, use "about" instead of "approximately," "use" instead of "utilize," and "help" instead of "facilitate" [30].

- Replace medical jargon with plain language. Do not provide the jargon and the definition in parentheses; simply use the plain term [30]. For instance, use "high blood pressure" instead of "hypertension."

- Be consistent with terminology (e.g., use "study drug" consistently, not alternating with "investigational medication") [29].

Sentence Structure:

Document Formatting:

- Use a 12-point sans-serif font (e.g., Arial, Calibri) [30].

- Ensure margins are at least 1 inch to provide ample white space [30].

- Use left-justified, right-ragged text alignment to give readers visual cues [30].

- Keep paragraphs short and focused on one idea [29].

- Use bulleted or numbered lists for three or more items [30].

- Highlight critical points using bold or italics, but avoid using ALL CAPS or excessive highlighting, which can reduce readability [29] [30].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Consent Document Development

| Tool / Resource Name | Function / Utility | Specific Application in ICF Development |

|---|---|---|

| Microsoft Word Readability Statistics | Built-in software tool to calculate Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Flesch Reading Ease. | Provides an immediate, quantitative assessment of a draft ICF's reading difficulty [29]. |

| Online Readability Checkers | Web-based platforms (e.g., Automatic Readability Checker) that analyze text passages. | Offers an alternative or verification method for readability scores independent of word processing software [30]. |

| Layperson Reviewer | A non-exist, non-colleague who represents the potential study population. | Performs a "comprehension check" by reading the ICF and explaining the study back in their own words; identifies confusing jargon or concepts [29] [30]. |

| Plain Language Thesaurus/Websites | Online glossaries (e.g., "Everyday Words for Public Health Communication" from CDC) that suggest simple alternatives for complex terms. | Aids in the systematic replacement of scientific and technical jargon with language accessible to a lay audience [29] [30]. |

| "Teach Back" Method | A communication protocol wherein the participant is asked to state what they have learned in their own words. | Used during the consent process (post-document development) to verify and confirm understanding of the study information [27]. |

Advanced Considerations and Protocol Validation

- Comprehension vs. Readability: Readability scores are a measure of reading difficulty, not a direct measure of understanding. A document can be written at a low grade level but still address concepts that are difficult to grasp [28]. Therefore, readability must be paired with techniques that verify conceptual comprehension, such as the Teach Back method [27].

- Electronic Informed Consent (eIC): Digital platforms for consent are increasingly common. Studies show that eIC can support comprehension comparable to paper, enhance the completeness of required fields, and does not impose a significant technology burden on participants [31]. eIC platforms can integrate multimedia elements (videos, interactive quizzes) that may further improve understanding.

- Protocol for Non-English Speaking Participants: For participants who do not speak English, a simple translation of a complex English form is insufficient. The short-form consent process, which involves an interpreter and an impartial witness, can be used for initial enrollment under certain conditions. However, for FDA-regulated studies, a fully translated consent form in the participant's language must be provided promptly after the short form is used [32].

Preparing an informed consent document using plain language at an 8th-grade reading level is a critical and achievable component of obtaining valid informed consent. By adhering to a structured protocol that involves iterative drafting guided by plain language principles, objective readability testing, and validation through layperson review, researchers can create documents that truly honor the ethical principle of respect for persons. This rigorous approach to communication minimizes the gap between disclosure and comprehension, thereby strengthening the integrity of the entire clinical research process.

Obtaining valid informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical clinical research, serving as the primary mechanism for protecting participant autonomy and rights. The process transcends mere regulatory compliance, representing a fundamental ethical commitment to participant understanding and voluntary participation. The complexity of modern clinical trials, however, presents significant challenges to achieving genuine comprehension. The Key Information Section (KIS) has emerged as a critical structured approach to enhancing participant understanding by presenting core information in a clear, concise, and accessible format. This mandate represents a paradigm shift from legalistic documentation to participant-centered communication, requiring systematic implementation within the clinical trial protocol framework.

International guidelines, including the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) principles, emphasize that the investigator's fundamental duty is to ensure the welfare of participants under their care, which inherently includes guaranteeing that consent is properly informed and voluntarily given [33]. The updated SPIRIT 2025 statement, which provides evidence-based guidance for clinical trial protocols, reinforces this ethical foundation through enhanced reporting requirements for participant-facing materials [34]. Within this evolving regulatory landscape, the KIS functions not as another administrative hurdle but as a scientifically-validated tool for improving information retention and promoting meaningful consent.

Regulatory Framework and Core Components

Evolving Regulatory Standards

The mandate for a Key Information Section aligns with global regulatory trends emphasizing transparency and participant engagement. The SPIRIT 2025 statement introduces systematic requirements for protocol content, including explicit attention to how participants will be informed throughout the trial process [34]. This updated guidance consists of a 34-item checklist that serves as a foundational framework for protocol development, emphasizing completeness and transparency in describing trial procedures and participant interactions.

Regulatory authorities recognize that traditional consent documents often exceed reasonable comprehension levels for many participants. The KIS addresses this discrepancy by distilling complex trial information into essential elements that facilitate understanding. According to ICH-GCP perspectives, the sponsor holds ultimate responsibility for trial quality and participant safety, while investigators bear direct responsibility for proper consent acquisition [33]. This shared accountability necessitates careful attention to how key information is structured and presented throughout the consent process.

Essential Elements of the Key Information Section

The Key Information Section must present the most critical information that a prospective participant needs to make an informed decision. Based on regulatory guidance and human factors research, the following core components represent the minimum required elements:

- Purpose Statement: Clear explanation that the activity is research, what the study is designed to investigate, and who is being invited to participate.

- Trial Duration and Commitment: Realistic description of the expected time commitment, including the total study duration, number of study visits, and procedures involved at each visit.

- Foreseeable Risks and Discomforts: Prominent disclosure of the most serious and most frequent risks associated with the investigational product and study procedures.

- Potential Benefits: Balanced presentation of any potential direct benefits to participants, along with a clear statement that there may be no direct benefit.

- Alternative Options: Description of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment that might be advantageous to the participant outside the research context.

- Voluntary Participation and Withdrawal Rights: Explicit statements that participation is voluntary, that refusal to participate involves no penalty or loss of benefits, and that the participant may discontinue participation at any time.

- Compensation and Treatment for Injury: Clear information about whether any compensation or medical treatment is available for research-related injuries.

Quantitative Analysis of KIS Implementation

SPIRIT 2025 Protocol Requirements for Participant Communication

The updated SPIRIT 2025 statement provides specific checklist items relevant to structuring information for participants and obtaining valid consent. The following table summarizes the key protocol requirements:

Table 1: SPIRIT 2025 Checklist Items Relevant to Informed Consent and Participant Communication

| Section | Item No. | Checklist Item Description | Relevance to KIS Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative Information | 1b | Structured summary of trial design and methods | Provides foundation for KIS content development |

| Open Science | 8 | Plans to communicate trial results to participants | Extends transparency beyond initial consent process |

| Introduction | 9a | Scientific background and rationale, including benefits and harms | Informs risk-benefit communication in KIS |

| Methods | 11 | Details of patient or public involvement in design, conduct, and reporting | Supports participant-centered KIS development |

| Ethics and Dissemination | 31 | Plans for seeking informed consent | Requires description of consent process including KIS |

| Ethics and Dissemination | 33 | How and by whom informed consent will be obtained | Ensures proper implementation of KIS in consent process |

Research Reagent Solutions for Consent Comprehension Assessment

Validating the effectiveness of the Key Information Section requires methodological rigor. The following table details essential methodological tools and approaches for developing and testing KIS comprehensibility:

Table 2: Essential Methodological Tools for KIS Development and Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Instrument/Approach | Function in KIS Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Readability Metrics | Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, SMOG Index | Quantifies reading level and identifies complex language requiring simplification |

| Comprehension Assessment | Validated questionnaires, Teach-back method | Measures actual understanding of key trial concepts after KIS review |

| Participant Engagement Tools | eConsent platforms with embedded multimedia | Enhances KIS presentation through interactive elements and visual aids |