The Evolution of Bioethics in the United States: From Historical Foundations to Modern Institutionalization

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the historical emergence and institutionalization of bioethics in the United States, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Evolution of Bioethics in the United States: From Historical Foundations to Modern Institutionalization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the historical emergence and institutionalization of bioethics in the United States, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational scandals and socio-political forces that shaped the field, details the development of key ethical frameworks and regulatory bodies like IRBs, examines persistent challenges in human subject protection and policy, and compares the distinct professionalization of bioethics in the U.S. versus other national contexts. The synthesis offers critical insights for navigating contemporary ethical dilemmas in biomedical research and clinical practice.

Origins and Catalysts: The Historical Forces that Forged American Bioethics

The period between the adoption of the American Medical Association's (AMA) Code of Ethics in 1847 and the promulgation of the Nuremberg Code in 1947 represents a foundational epoch in the history of medical ethics and the emergence of modern bioethics. This two-century span witnessed a profound transformation in the ethical governance of medicine, shifting from a framework of internal professional etiquette toward one encompassing universal human rights and explicit protections for individuals in the context of scientific research. This evolution was driven by unprecedented scientific advances, egregious ethical failures in human experimentation, and significant socio-legal challenges to medical paternalism. This whitepaper traces these key historical precedents, situating them within the broader thesis of bioethics' institutionalization in the United States. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this historical trajectory is crucial for appreciating the ethical underpinnings of contemporary regulatory frameworks governing human subjects research.

The AMA Code of Medical Ethics (1847): Codifying Professional Conduct

The Code of Medical Ethics adopted at the inaugural meeting of the American Medical Association in 1847 marked the first formal attempt to codify medical ethics in the United States [1]. Its creation was a primary objective for the newly formed professional body, reflecting a desire to establish medicine as a self-regulating profession with defined standards of conduct.

Historical Context and Founding Principles

The 1847 Code drew heavily from the work of English physician Thomas Percival, who published his Code of Medical Ethics in 1803 [1]. Percival's work outlined professional duties and ideal behavior, particularly in the context of hospitals and charitable organizations. The AMA, in adopting and adapting this framework, sought to safeguard the public and uphold the honor and dignity of the medical profession. The Code was structured around three core components, a structure that persists in the AMA's ethics governance today:

- The Principles of Medical Ethics: Broad standards defining the essentials of honorable behavior.

- Ethical Opinions of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: Application of the principles to specific professional issues.

- Reports of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: In-depth studies and policy recommendations on emerging ethical questions [1].

This structure allowed for the establishment of foundational norms while creating a mechanism for addressing new challenges in medical practice.

Key Tenets and Limitations

The original 1847 Code and its subsequent revisions emphasized the physician's duty to humanity and the importance of improving medical knowledge and skill [1]. A key feature was its focus on professional self-regulation, urging physicians to "expose, without hesitation, illegal or unethical conduct of fellow members of the profession" [1]. This created a system of ethics that was largely internal to the profession, focusing on the character and conduct of the physician rather than on the rights of the patient. The physician-patient relationship was implicitly hierarchical, grounded in the belief that the physician's knowledge and benevolence warranted patient trust and submission. The Code functioned more as a guide for "honorable behavior" among professionals than as a enforceable set of patient-centric rules [1].

Table 1: Evolution of the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics

| Year of Revision | Key Characteristics and Changes |

|---|---|

| 1847 | Original code, based on Percival's work; focused on professional duties, honor, and self-regulation. |

| 1957 | Major revision to distinguish medical ethics from medical etiquette; contained 10 succinct sections [1]. |

| 1980 | Balanced professional standards with legal requirements; removed language against association with unscientific practitioners; introduced gender-neutral language [1]. |

| 2001 | Added two new principles: patient responsibility as paramount and support for access to medical care for all people [1]. |

The Nuremberg Code (1947): A Response to Atrocity

The Nuremberg Code emerged directly from the aftermath of World War II, during the Doctors' Trial of 1947, where medical professionals were prosecuted for war crimes and crimes against humanity for their participation in brutal human experiments [2]. The Code was articulated by the court as a set of principles for permissible medical experimentation, establishing a new, rights-based foundation for research ethics.

Historical Context and Catalyzing Events

The Nazi medical experiments, which included exposure to freezing temperatures, high altitude, deadly diseases, and other tortures, demonstrated a catastrophic failure of existing medical ethical frameworks [2]. The Code was the judicial response to this failure, an attempt to establish clear, absolute boundaries for scientific research involving human beings. It represented a radical departure from the professional self-regulation model of the AMA Code, introducing universal standards intended to protect the individual's rights and integrity against the power of the state and the scientific enterprise.

Foundational Ethical Principles

The Nuremberg Code consists of ten directives, the first and most fundamental being the requirement for voluntary consent of the human subject [2]. This principle, along with others in the Code, fundamentally reoriented the ethical landscape.

Table 2: Core Directives of the Nuremberg Code (1947)

| Principle | Directive | Impact and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Consent | "The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential." [2] | Establishes the autonomous right of the individual to choose what happens to their own body. |

| Social Value | The experiment should yield "fruitful results for the good of society." [2] | Requires that research have a valuable scientific purpose to justify any risk. |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment | Risks should never exceed humanitarian importance; based on prior animal experimentation. [2] | Introduces the concept of proportionality and scientific rationale. |

| Investigator Responsibility | The scientist must be prepared to terminate the experiment if it is likely to cause injury, disability, or death. [2] | Places ultimate responsibility for the subject's welfare on the lead researcher. |

| Subject Autonomy | The human subject must be "at liberty to bring the experiment to an end." [2] | Affirms the ongoing right of the subject to withdraw consent at any time. |

The Code's emphasis on informed, voluntary consent directly challenged the paternalistic "doctor knows best" model that had previously dominated medicine and research [3] [4]. It positioned the research subject not as a passive recipient of intervention, but as an autonomous agent who must understand the risks and benefits and freely agree to participate.

The Intervening Century: Paving the Way for Bioethics

The century between the AMA Code and the Nuremberg Code was not an ethical vacuum. Scientific progress and societal changes created the conditions for a radical rethinking of medical ethics, culminating in the principles articulated at Nuremberg.

The Rise of Scientific Medicine and its Ethical Challenges

The post-World War II era saw rapid acceleration in medical capabilities, with the development of antibiotics, vaccines, and complex surgeries [3]. This "era of modern medicine" fostered an environment of optimism but also created unprecedented ethical dilemmas. Physicians, armed with new technologies, began to see themselves as "applied scientists" battling disease, sometimes at the cost of viewing the patient as merely "the locus of disease" [3]. This technological imperative, while saving lives, often marginalized the patient's subjective experience and personal preferences, creating a gap between medical capability and humanistic care.

The Influence of Consumer Rights and Legal Doctrine

Beginning in the mid-20th century, social and legal forces began to erode medical paternalism. The 1957 Salgo case introduced the legal doctrine of informed consent, ruling that physicians must provide patients with relevant information about risks and alternatives [3]. The court decreed that it was the patient, not the physician, who should decide how to balance risks and benefits. This legal precedent dovetailed with a growing consumer rights movement. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy outlined four core consumer rights: the right to safety, the right to be informed, the right to choose, and the right to be heard [3]. This rights-based discourse provided a powerful cultural framework for demanding greater patient autonomy and transparency in medicine, directly feeding into the emerging bioethics movement.

Institutionalization of Bioethics: From Principles to Practice

The principles of Nuremberg required institutional mechanisms to be integrated into the everyday practice of research and medicine. This process of institutionalization was a critical step in the history of bioethics.

The Founding of Bioethics Institutions

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the establishment of dedicated institutions that would professionalize and advance the field of bioethics. Key among these were:

- The Hastings Center (1969): Founded to address ethical problems emerging faster than the medical profession could address internally, it helped define the direction, methods, and intellectual standards of the new field of "bioethics" [3].

- The Kennedy Institute of Ethics (1971): Became another central bastion for bioethics scholarship and education [3].

These institutions provided a permanent home for interdisciplinary scholarship, moving beyond the ad-hoc responses of the past and creating a sustained discourse around the ethical dimensions of medicine and the life sciences.

National Commissions and Federal Policy

The U.S. government formalized its engagement with bioethics through a series of presidential and congressional commissions, which translated ethical principles into concrete policy.

- The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects (1974-78): This first national bioethics commission produced the Belmont Report, which distilled the principles of Nuremberg and others into three core ethical principles for research: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [5]. The Belmont Report became the ethical foundation for U.S. federal regulations governing human subjects research.

- Subsequent Bioethics Commissions: Later commissions, such as the Presidential Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and the President's Council on Bioethics, continued this work, issuing influential reports on topics ranging from the definition of death to stem cell research and genetic sequencing [5].

These commissions served as a critical bridge, translating the grand principles of Nuremberg into actionable guidelines and regulations that now govern the work of all researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in the United States.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A critical examination of key experiments cited in the formation of bioethics reveals the methodological and ethical failures that necessitated this historical evolution.

Methodology of the Beecher Study (1966)

Henry Beecher's 1966 article in the New England Journal of Medicine was a watershed moment, documenting 22 examples of unethical research in the post-war period [3]. His methodology was not a controlled experiment but a qualitative, evidence-based exposé.

- Data Collection: Beecher compiled concrete examples from the published medical literature of studies that he argued violated ethical norms.

- Analysis: He identified a common failure: the failure to inform patients of the risks involved in experimental treatments. His examples illustrated that unethical research was not an isolated problem but a systemic one.

- Proposed Safeguard: Beecher's primary conclusion was that the most "reliable safeguard" was "the presence of an intelligent, informed, conscientious, compassionate, responsible investigator" [3]. This reflected a belief in the power of individual professional virtue, a perspective that would soon be supplemented by the systemic, regulatory approach demanded by the Nuremberg Code.

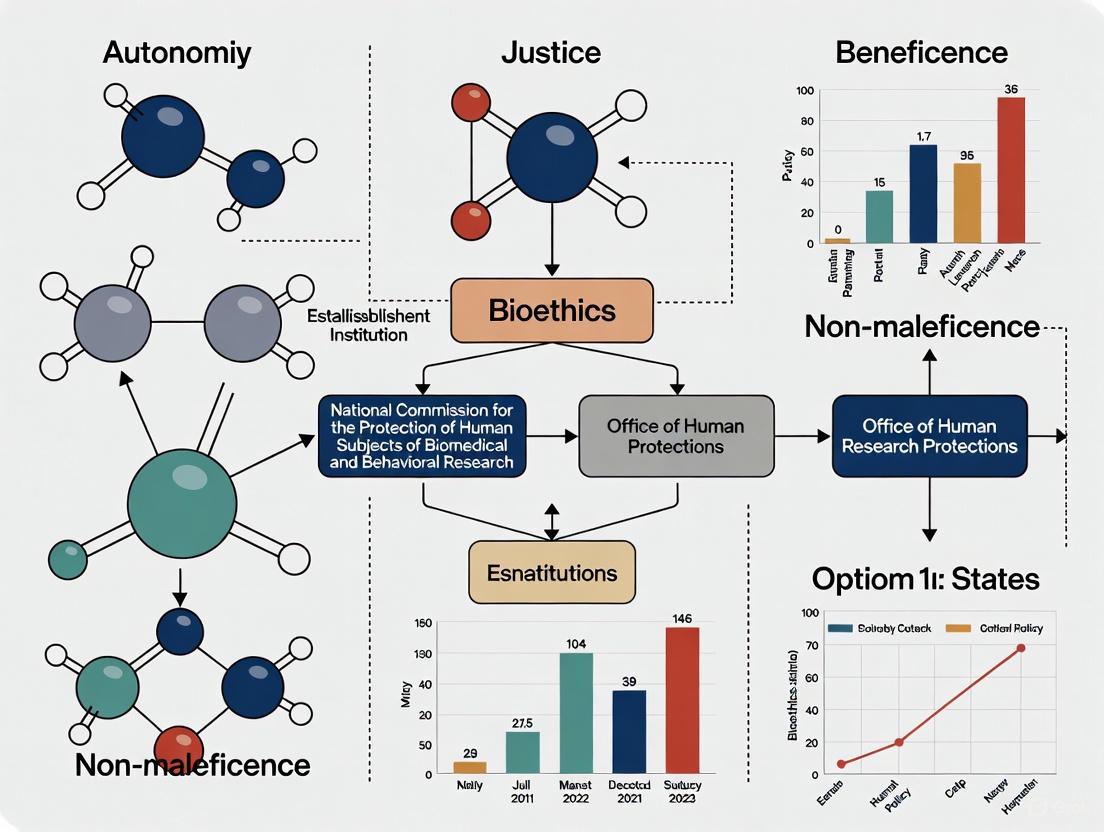

Visualization of the Historical Trajectory

The logical relationships between the key historical precedents, their catalysts, and their outcomes can be visualized in the following flowchart, which maps the evolution from professional ethics to institutionalized bioethics.

Diagram 1: The historical trajectory from the AMA Code to institutionalized bioethics, showing key catalysts (red), contributing factors (blue), and foundational outcomes (green).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key conceptual "reagents" that were essential in the experiments and ethical developments discussed in this whitepaper. For the historical researcher of bioethics, these concepts are the essential materials for analysis.

Table 3: Key Conceptual "Research Reagents" in the History of Bioethics

| Conceptual Item | Function in the Historical Context |

|---|---|

| Informed Consent | The legal and ethical doctrine, crystallized in the Salgo case and the Nuremberg Code, that functions to protect individual autonomy by ensuring a subject's consent is voluntary, competent, and informed [3] [2]. |

| Principle of Voluntary Consent | The foundational "reagent" of the Nuremberg Code, acting as the primary ethical barrier against coercive or non-consensual human experimentation [2]. |

| Professional Self-Regulation | The mechanism, central to the 1847 AMA Code, by which the medical profession internally policed its members' conduct through peer pressure and exposure of misconduct [1]. |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | The structural entity created as a result of the National Commission's work (Belmont Report) to provide independent, external oversight of research protocols to ensure ethical conduct and protect human subjects. |

| The Belmont Principles | A standardized "solution" of three core principles (Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice) used to ethically analyze and guide research involving human subjects [5]. |

The journey from the AMA Code of 1847 to the Nuremberg Code of 1947 illustrates a fundamental shift from an internal, profession-centric model of ethics to an external, rights-based one. This transition was catalyzed by the horrific failures of ethics in the Nazi era, but was also shaped by the growing power of scientific medicine, the rise of consumer rights, and pivotal legal doctrines like informed consent. The subsequent institutionalization of bioethics through dedicated centers and national commissions ensured that the principles articulated at Nuremberg would become embedded in the fabric of American research and clinical practice. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, this history is not merely academic; it is the direct antecedent of the regulatory and ethical environment in which they operate. Understanding these key historical precedents is essential for conducting scientifically sound and ethically rigorous research in the 21st century.

The U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee stands as a defining scandal in biomedical research history. Conducted from 1932 to 1972, this 40-year observational study deliberately withheld effective treatment from 399 African American men with syphilis to document the disease's natural progression [6] [7]. This review examines the study's methodological framework, ethical violations, and its pivotal role in institutionalizing bioethics within United States research policy. The subsequent creation of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research and the Belmont Report established foundational principles—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—that continue to govern human subjects research today [8] [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this legacy is crucial for maintaining ethical integrity in contemporary clinical trials and biomedical innovation.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study emerged within a complex historical context of scientific inquiry and profound social inequality. The early 20th century witnessed unprecedented advances in scientific medicine, including the development of sulfa drugs and penicillin, which created an environment of therapeutic optimism [3]. Simultaneously, the scientific community held racially biased views regarding disease manifestation, with prominent physicians suggesting syphilis presented differently in African Americans than in whites [8]. This conjecture provided partial motivation for the study, building upon previous observational research like the Oslo Study of Untreated Syphilis conducted in Norway [7] [10].

The study was conducted in Macon County, Alabama, where 82% of residents were African Americans living in poverty with limited access to healthcare [8] [7]. Researchers capitalized on these vulnerable socioeconomic conditions to recruit participants. The PHS, in collaboration with the Tuskegee Institute, initiated the study under the guise of providing healthcare, misleading participants by describing the research as "treatment for bad blood"—a local colloquialism for various ailments including syphilis and anemia [6] [10]. What began as a short-term observational study evolved into a decades-long experiment that continued despite the availability of effective treatment, ultimately becoming what is now widely considered "arguably the most infamous biomedical research study in U.S. history" [10].

Study Methodology and Ethical Violations

Experimental Design and Protocols

The Tuskegee Study's methodological framework was designed to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis in African American males, constituting a prospective cohort study that deviated fundamentally from ethical research practices.

Table 1: Tuskegee Study Cohort Composition

| Group | Number of Participants | Condition | Observation Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syphilitic Group | 399 | Latent or late syphilis | 1932-1972 |

| Control Group | 201 | No syphilis | 1932-1972 |

Participants were recruited through deceptive practices, with researchers promising free medical care, meals, and burial insurance as incentives for participation [6] [7]. The study population consisted exclusively of African American men aged 25 years or older, primarily impoverished sharecroppers with limited education and healthcare access [7] [11]. Notably, no women were included in the study, though subsequent investigations revealed that some wives of participants contracted syphilis through transmission [6].

The methodological approach involved periodic monitoring through physical examinations and diagnostic procedures, including lumbar punctures that were deceptively described as "special free treatment" [7]. When penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis in 1947, researchers systematically withheld this therapy and actively prevented participants from accessing treatment through other healthcare providers [10] [12]. This deliberate non-intervention persisted despite the establishment of PHS "rapid treatment centers" across the country aimed at eradicating the disease [7].

Key Ethical Violations

The study violated multiple fundamental ethical principles through systematic deception and harm:

- Informed Consent: Researchers never obtained informed consent from participants and deliberately withheld information about their syphilis diagnosis [6] [7]. Participants were misled into believing they were receiving therapeutic treatment for "bad blood" rather than understanding they were research subjects in an observational study [10].

- Withholding Treatment: The most egregious ethical violation was the deliberate withholding of effective treatment. Even after penicillin became widely available as a safe and effective cure in the mid-1940s, researchers continued to deny treatment to participants [6] [12]. Researchers went so far as to provide local physicians with lists of study participants and requested that they not be treated [7].

- Deception and Coercion: Researchers employed multiple deceptive practices, including describing diagnostic procedures such as lumbar punctures as therapeutic interventions [7]. The promise of burial insurance acted as a coercive inducement, particularly given the economic circumstances of participants [7] [10].

- Harm to Third Parties: The ethical violations extended beyond the study participants to their families. As a result of untreated syphilis, some wives contracted the disease, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis [10] [12].

Diagram 1: Ethical Violation Framework in the Tuskegee Study

The Path to Exposure and Institutional Response

Whistleblowing and Public Exposure

The Tuskegee Study continued for four decades despite internal and external concerns. The first known formal objection from a medical professional came in 1965 when Dr. Irwin Schatz wrote to the PHS condemning the study's morality [8]. The following year, Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal disease investigator, began raising ethical concerns about the study with his superiors [7] [12]. In response, the PHS convened a panel in 1969 to review the study, but the committee—which included neither African Americans nor medical ethicists—recommended continuing the research without significant changes [8].

Frustrated by the lack of institutional response, Buxtun eventually contacted journalist Jean Heller of the Associated Press, who broke the story in July 1972 [7] [12]. The public revelation triggered widespread outrage and led to congressional hearings in 1973 [10] [12]. The subsequent investigation by an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel concluded the study was "ethically unjustified" and ordered its immediate termination in 1972 [6].

Legal Settlement and Presidential Apology

In 1974, the U.S. government reached a $10 million out-of-court settlement in a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of the study participants and their families [6] [12].

Table 2: Distribution of 1974 Settlement Funds

| Recipient Category | Number Qualified | Settlement Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Living syphilitic participants | Not specified | $37,500 |

| Heirs of deceased syphilitic participants | Not specified | $15,000 |

| Living control group participants | Not specified | $16,000 |

| Heirs of deceased control group participants | Not specified | $5,000 |

Twenty-five years after the study's termination, President Bill Clinton issued a formal presidential apology on May 16, 1997, stating, "The United States government did something that was wrong—deeply, profoundly, morally wrong" [12]. The apology ceremony included one of the last surviving study participants and announced the establishment of The National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care at Tuskegee University [6].

Institutionalization of Bioethics: Regulatory Transformations

The Belmont Report and Ethical Frameworks

The exposure of the Tuskegee Study served as a catalyst for the systematic institutionalization of bioethics in the United States. In 1974, Congress passed the National Research Act, which created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [9]. This commission was tasked with identifying the basic ethical principles that should underlie research involving human subjects.

In 1979, the Commission published the Belmont Report, which established three fundamental ethical principles for research involving human subjects [8] [9]:

- Respect for Persons: Recognizing the autonomy of individuals and requiring protection for those with diminished autonomy, implemented through informed consent processes.

- Beneficence: Obligating researchers to maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms, implemented through systematic risk-benefit assessment.

- Justice: Requiring fair distribution of the benefits and burdens of research, preventing the exploitation of vulnerable populations.

The Belmont Report provided the ethical foundation for subsequent regulations and continues to influence research ethics oversight to this day [8].

Regulatory Infrastructure and Oversight

The post-Tuskegee regulatory landscape established systematic oversight mechanisms for human subjects research:

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): The 1974 regulations required that all research supported by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) be reviewed by IRBs to ensure protocols met ethical standards [9]. This system of local institutional oversight has since expanded to encompass nearly all human subjects research regardless of funding source.

- Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects: In 1991, 16 federal departments and agencies adopted the Common Rule (Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects), creating a unified set of regulations for human research protection [9].

- Ongoing Bioethics Oversight: Subsequent advisory bodies have continued to refine research ethics oversight, including the National Bioethics Advisory Commission (1995-2001), the President's Council on Bioethics (2001-2009), and the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues (2009-2017) [9].

Diagram 2: Evolution of U.S. Research Ethics Governance After Tuskegee

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Ethics and Historical Context

Historical Research Methods and Materials

Understanding the historical context of research methods employed in the Tuskegee Study provides crucial insights for contemporary research ethics.

Table 3: Research Methods and Materials in Historical Context

| Method/Material | Historical Application in Tuskegee | Contemporary Ethical Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Recruitment | Deceptive appeal through "bad blood" treatment promises; exploitation of vulnerable population | Transparent informed consent; vulnerability protections; equitable selection |

| Diagnostic Procedures | Lumbar punctures misrepresented as "special treatment" | Full disclosure of diagnostic nature and risks; therapeutic misconception avoidance |

| Placebo Administration | Disguised placebos and ineffective treatments (aspirin, mineral supplements) given without disclosure | Placebo use only with disclosure and when no proven treatment exists |

| Disease Monitoring | Ongoing observation without intervention despite available treatment | Immediate provision of effective treatment when available; study termination when definitive treatment discovered |

| Treatment Withholding | Intentional prevention of penicillin access despite established efficacy | Obligation to provide best proven intervention; independent ethics review |

Lasting Impact on Research Practice

The Tuskegee Study's legacy has profoundly shaped contemporary research practice, particularly in several key areas:

- Informed Consent Processes: Modern research requires comprehensive informed consent procedures that include disclosure of relevant information, participant comprehension, and voluntary participation [8] [9]. This represents a direct response to the deceptive practices employed in Tuskegee.

- Vulnerable Population Protections: Additional safeguards have been implemented for vulnerable populations, including economically disadvantaged individuals, racial minorities, and those with limited autonomy [8] [13]. The principle of justice requires equitable selection of research subjects to prevent exploitation of vulnerable groups.

- Transparency and Accountability: Requirements for data monitoring, interim analysis, and early study termination when benefits or harms become clear have been strengthened to prevent the continuation of unethical research [9].

- Cultural Competence and Community Engagement: The legacy of distrust generated by Tuskegee has emphasized the importance of community engagement and cultural competence in research, particularly when working with historically marginalized populations [14].

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study represents a critical juncture in the history of research ethics, serving as a catalyst for the systematic institutionalization of bioethics in the United States. Its lasting impact continues to resonate through the regulatory infrastructure, ethical frameworks, and professional practices that govern contemporary biomedical research.

For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this history is not merely an academic exercise but an essential component of ethical practice. The study illustrates how scientific curiosity, when divorced from ethical considerations, can cause profound harm. It demonstrates the necessity of robust oversight mechanisms, including IRB review and informed consent processes. Most importantly, it underscores the ethical imperative to protect vulnerable populations and maintain public trust in scientific research.

While empirical studies have shown no direct association between knowledge of Tuskegee and willingness to participate in research [14], the study remains a powerful symbol of research abuse and a reminder of the ongoing need for vigilance in maintaining the highest ethical standards. As we confront new ethical challenges in emerging fields such as genomics, artificial intelligence, and global health research, the lessons of Tuskegee remain profoundly relevant—reminding us that scientific progress must always be guided by unwavering commitment to ethical principles and respect for human dignity.

The 1970s marked the formal institutionalization of bioethics as a distinct field in the United States, emerging from a powerful convergence of social upheaval, technological advancement, and political response. This decade witnessed the transformation of ethical concerns regarding medicine and biology from matters of professional self-regulation into a public discourse characterized by interdisciplinary scholarship and formal government oversight. The emergence of bioethics during this period represented a fundamental shift from the Hippocratic tradition of physician paternalism toward a new framework centered on patient autonomy and informed consent [15]. This article examines the historical context, key developments, and lasting institutional frameworks established during this formative decade, with particular attention to their significance for contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Historical Backdrop: Pre-1970s Medical Ethics and the Catalysts for Change

The Pre-Bioethics Landscape

Prior to the 1970s, medical ethics in the United States operated largely within a Hippocratic framework characterized by physician paternalism, where doctors made treatment decisions based on their judgment of what was best for patients, often without substantive patient consultation [15]. This approach was codified in medical ethics codes, including the American Medical Association's first Code of Medical Ethics in 1847, which emphasized the physician's duty to decide for the patient rather than with the patient [16]. Medical decision-making was largely opaque to patients, with studies as late as 1961 revealing that 88% of physicians did not disclose cancer diagnoses to patients [15].

Table 1: Key Pre-1970s Developments Leading to Bioethics

| Year | Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1847 | AMA Code of Medical Ethics | Formalized physician-centered Hippocratic tradition |

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code | Established informed consent requirement for research |

| 1961 | Home pregnancy test available | Increased patient autonomy in reproductive health |

| 1966 | Henry Beecher's ethical research exposé | Revealed widespread ethical lapses in human subjects research |

The Social and Political Context

The 1960s and 1970s provided a fertile ground for challenges to medical paternalism, coinciding with broader social movements questioning traditional authority structures [16]. The civil rights movement, consumer advocacy, and anti-war protests created an environment receptive to calls for greater individual autonomy and transparency in medicine and research [3]. President John F. Kennedy's 1962 Consumer Bill of Rights articulated principles that would later resonate strongly with bioethics: the right to safety, right to be informed, right to choose, and right to be heard [3]. Simultaneously, political scandals like Watergate fostered public skepticism toward institutional authority and demands for accountability across American society [16].

The Decade of Convergence: Social, Technological, and Political Forces in the 1970s

Technological Advances and Ethical Challenges

The 1970s witnessed unprecedented technological developments that presented novel ethical questions beyond the scope of traditional medical ethics:

- Reproductive technologies: Safe birth control methods, home pregnancy tests, and the first successful in vitro fertilization (resulting in the birth of Louise Brown in 1978) created new ethical dimensions in human reproduction [16].

- Organ transplantation: Improved techniques in solid organ transplantation raised complex questions about resource allocation and patient selection criteria [16].

- Life-sustaining technologies: Advances in critical care medicine forced confrontation with questions about quality of life, medical futility, and the definition of death [17].

- Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM): Widespread adoption despite unproven efficacy, demonstrating persistent paternalism in obstetrics even as bioethics emerged in other areas [15].

Research Scandals and the Crisis of Trust

Several highly publicized research scandals during this period eroded public trust in the medical establishment and created political pressure for reform:

- The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (publicly exposed in 1972): This 40-year study by the U.S. Public Health Service withheld treatment from African American men with syphilis even after penicillin became available [16]. The scandal prompted congressional hearings and "shocked the government and research community" [16].

- Human radiation experiments: Revelations that the government had conducted human radiation experiments without consent further damaged trust [17].

- Other research abuses: Henry Beecher's 1966 landmark article had previously exposed 22 examples of unethical human subjects research, but meaningful reforms awaited the political pressure of the 1970s [3].

These scandals highlighted the insufficiency of professional self-regulation and created an imperative for external oversight and formal ethical frameworks.

The Rise of Patient Autonomy and Informed Consent

The 1970s witnessed the legal formalization of informed consent as a cornerstone of both clinical practice and research ethics. The 1972 case Canterbury v. Spence established the principle that "knowing, informed consent by the patient is a prerequisite to ethical medical care" [16]. This legal doctrine emerged before its widespread acceptance in medical ethics, demonstrating law's role in shaping bioethical practice [16]. The principle of autonomy gained further traction through its incorporation into federal regulations, particularly after the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects embedded respect for persons as a fundamental principle in what would become the Belmont Report [18].

Table 2: Landmark Legal Cases of the 1970s Shaping Bioethics

| Case | Year | Legal Principle | Bioethical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canterbury v. Spence | 1972 | Informed consent prerequisite | Established patient autonomy over physician paternalism |

| Roe v. Wade | 1973 | Constitutional right to privacy | Affirmed reproductive autonomy |

| Tarasoff v. Regents of UC | 1976 | Duty to warn | Balanced confidentiality with public protection |

Institutionalization of Bioethics: Foundations of a New Field

Founding of Bioethics Institutions

The 1970s witnessed the establishment of dedicated institutions that provided bioethics with organizational infrastructure and scholarly legitimacy:

- The Hastings Center (1969): Founded in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, this research institute became instrumental in "setting the direction, methods, and intellectual standards of bioethics" through its journal, the Hastings Center Report [3].

- The Kennedy Institute of Ethics (1971): Established at Georgetown University as an academic center for bioethics scholarship and education [3].

- Interfaculty Program in Bioethics at Harvard University: Exemplified early academic institutionalization of bioethics as an interdisciplinary endeavor [18].

These institutions provided the physical and intellectual space for collaboration among philosophers, theologians, lawyers, physicians, and social scientists, creating the distinctive interdisciplinary character of bioethics [3].

Government Commissions and Formal Policy

The U.S. government played a crucial role in legitimizing bioethics through the creation of official advisory bodies:

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects (1974-1978): Established by the National Research Act of 1974 as the first national bioethics commission [17]. Its creation was a direct response to the Tuskegee scandal and broader concerns about research ethics [19].

- The Belmont Report: Produced by the National Commission in 1979, this document identified three fundamental principles for research ethics—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—which became the foundation for subsequent federal research regulations [18] [17].

- Presidential Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine (1978-1983): Continued the work of the National Commission with an expanded mandate to address broader ethical issues in medicine and research [17].

These commissions represented the formal incorporation of bioethical analysis into democratic governance of science and medicine [19].

Intellectual Frameworks and Methodologies

The intellectual content of bioethics coalesced during the 1970s around several distinctive approaches:

- Principlism: Tom Beauchamp and James Childress's 1979 book Principles of Biomedical Ethics organized the field around four key principles: autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice [18]. This framework became dominant in clinical ethics consultation and research ethics review.

- Interdisciplinarity: Despite the later dominance of philosophical approaches, early bioethics intentionally brought together multiple disciplines, including law, theology, philosophy, and medicine [18].

- Case-based reasoning: Bioethics developed methodologies that moved between theoretical principles and concrete cases, bridging abstract ethical theory and practical clinical dilemmas.

The following diagram illustrates the convergence of factors that led to the institutionalization of bioethics in the 1970s:

Critical Analysis: Tensions and Limitations in the 1970s Bioethics Framework

Philosophical and Disciplinary Tensions

The institutionalization of bioethics during the 1970s was not without internal tensions and critical omissions:

- Dominance of philosophical approaches: Despite early interdisciplinary intentions, philosophers became the "dominant force in the field" by the mid-1970s, marginalizing social scientists and other disciplinary perspectives [18].

- Applied ethics paradigm: Bioethics came to be viewed primarily as "applied ethics," creating what critics called a "cultural myopia" that abstracted ethical questions from their social, economic, and historical contexts [18].

- Individualistic orientation: The focus on autonomy and individual rights reflected American political discourse but sometimes neglected broader considerations of social justice and structural determinants of health [20].

Persistent Paternalism in Medical Practice

Despite the emergence of bioethics, some areas of medicine resisted the shift toward patient autonomy. Most notably, electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) became widespread during the 1970s without informed consent, "epitomizing medical paternalism" despite unproven efficacy and potential harms [15]. This exception demonstrates that the transformation from physician-centered to patient-centered medicine remained incomplete.

The Exclusion of Historical Perspectives

Historians largely remained outside the emerging bioethics discourse, despite early collaborations. By the 1980s, historians criticized bioethics for decontextualizing ethical issues and failing to acknowledge how moral values are "historically constructed and situationally negotiated" [18]. This historical blind spot would limit bioethics' ability to address persistent structural inequities in healthcare.

Research Methodology: Analyzing the Development of Bioethics

Primary Source Analysis

Research into the development of 1970s bioethics relies on several key categories of primary sources:

- Government documents: Congressional hearing records, commission reports (including the Belmont Report), and federal regulations [19] [17].

- Archival materials: Papers of key figures and institutions (e.g., Walter Mondale Papers, Hastings Center archives) [19].

- Legal cases: Court opinions from landmark bioethics cases establishing informed consent and other principles [16].

- Contemporary publications: Early bioethics literature, including articles in the Hastings Center Report and other emerging bioethics journals [3].

Interdisciplinary Synthesis

Methodological approaches must integrate multiple disciplinary perspectives:

- Historical analysis: Tracing the development of ideas, institutions, and policies over time.

- Philosophical analysis: Examining the logical coherence and normative foundations of ethical frameworks.

- Sociological approaches: Understanding bioethics as a professional field with specific social structures and practices.

- Legal analysis: Interpreting the regulatory and judicial frameworks that formalized bioethical principles.

Table 3: Key Methodological Tools for Bioethics Research

| Research Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Archival Research | Historical context development | Tracing legislative history of bioethics commissions |

| Case Analysis | Ethical reasoning refinement | Analyzing Canterbury v. Spence informed consent doctrine |

| Principle-Based Analysis | Framework for ethical evaluation | Applying Belmont Report principles to research protocols |

| Interdisciplinary Dialogue | Integrating multiple perspectives | Combining philosophical, legal, and clinical viewpoints |

The institutionalization of bioethics during the 1970s established enduring frameworks that continue to shape research and drug development. The principle-based approach formalized in the Belmont Report provides the foundation for contemporary Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and research oversight mechanisms [18] [17]. The emphasis on informed consent remains central to both clinical practice and human subjects research [16]. The interdisciplinary model of bioethics, despite its limitations, established a precedent for bringing diverse expertise to bear on complex ethical questions in medicine and biotechnology.

For contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this historical context is essential for several reasons. First, it reveals the ethical foundations underlying current regulatory requirements. Second, it provides insight into persistent tensions between scientific progress and ethical constraints. Third, it offers lessons for addressing emerging ethical challenges in areas such as genetics, artificial intelligence, and human enhancement, where—as in the 1970s—technological capabilities continue to outpace ethical frameworks.

The bioethics that emerged from the pivotal 1970s represents both a break from physician paternalism and a continuation of ongoing negotiations between expert authority and public accountability. Its frameworks, institutions, and principles continue to evolve in response to new technological and social challenges, but remain deeply shaped by the confluence of forces that defined their origins a half-century ago.

The institutionalization of bioethics in the United States represents a pivotal transformation in how society addresses ethical challenges arising from medical and scientific progress. This formalization process was profoundly shaped by three seminal thinkers: Van Rensselaer Potter, who coined the term "bioethics" and envisioned it as a global discipline bridging science and humanities; Andre Hellegers, who established the first academic bioethics institute and helped define the field's early institutional agenda; and Paul Ramsey, whose groundbreaking work provided the first systematic framework for addressing pressing medical ethical dilemmas. These pioneers represented diverse perspectives—oncology, obstetrics, and theological ethics respectively—yet collectively established the conceptual and institutional foundations for bioethics as a distinct field of inquiry. Their contributions emerged during a period of rapid medical advancement and social change in the 1960s and 1970s, when new technologies forced a reexamination of medicine's moral dimensions [3] [21]. This whitepaper examines their distinctive contributions and the enduring legacies they left on the institutionalization of bioethics within American research and clinical practice.

Van Rensselaer Potter: Coining a Discipline and the Original Vision of Global Bioethics

Conceptual Foundations and Key Publications

Van Rensselaer Potter, an American biochemist and professor of oncology, first introduced the term "bioethics" in 1970 as a "science of survival" aimed at addressing the fundamental problems of human flourishing [22]. His conceptualization was notably broader than how the field would later develop, envisioning bioethics as a bridge between biology, ecology, medicine, and human values. Potter's foundational work, Bioethics: Bridge to the Future (1971), argued for a discipline that would integrate biological knowledge with ethical reasoning to ensure long-term human survival on a threatened planet [23]. He described bioethics as forming a bridge "between present and future, nature and culture, science and values, and finally between humankind and nature" [22].

Disappointed that bioethics became largely synonymous with medical ethics, Potter later introduced the term "global bioethics" in his 1988 book Global Bioethics: Building on the Leopold Legacy [24]. He defined this as "Biology combined with diverse humanistic knowledge forging a science that sets a system of medical and environmental priorities for acceptable survival" [24]. Potter distinguished between two complementary approaches: medical bioethics with its short-term view focused on individual patient care, and environmental bioethics with a long-term perspective concerned with species survival [23]. For Potter, both were essential components of a comprehensive global bioethics that acknowledged the entanglement of science and ethics in a non-hierarchical relationship [23].

Table: Van Rensselaer Potter's Evolving Bioethics Framework

| Dimension | Initial Concept (1970-1971) | Later Refinement (1988) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | "Science of survival" and human flourishing | "Global bioethics" integrating environmental concerns |

| Scope | Bridge between biology, ecology, medicine, human values | Encompasses both medical and environmental ethics |

| Temporal View | Present to future orientation | Short-term (medical) and long-term (environmental) perspectives |

| Defining Metaphor | "Bridge to the future" | System of "medical and environmental priorities" |

Methodological Approach and Lasting Influence

Potter's methodology was characterized by holistic integration rather than disciplinary separation. He insisted that "ethical values cannot be separated from biological fact," though he advocated for a non-reductionist, ecological understanding of biology that acknowledged chance, feedback loops, and disorder as raw materials for creativity and ethical development [23]. His approach called for educated leaders trained in both science and humanities and even proposed a "Council on the Future" that would function as an independent fourth power alongside traditional government branches to safeguard long-term human interests [23].

While Potter's specific proposals received limited immediate institutional uptake, his core insight—that ethics must engage with broad environmental and future-oriented concerns—has experienced a resurgence in contemporary bioethics. Recent scholarship acknowledges that his original vision of a bioethics concerned with planetary health and survival is "more timely than ever" in an era of climate change and global health crises [22] [23]. Critics note that some aspects of his framework, particularly his focus on population control, reflected ableist assumptions and insufficient engagement with Global South perspectives [23]. Nevertheless, his foundational concept of bioethics as a bridge discipline continues to inform efforts to address the ethical dimensions of environmental crises and technological change.

Andre Hellegers: The Institutional Architect of Bioethics

Founding the Kennedy Institute of Ethics

Andre Hellegers, a Dutch-born obstetrician and fetal physiologist, played a pivotal role in institutionalizing bioethics through his founding of the Kennedy Institute of Ethics (KIE) at Georgetown University in 1971 [25]. While Potter coined the term, Hellegers was instrumental in establishing the first academic structures dedicated to the field. Hellegers brought to bioethics a distinctive combination of scientific expertise and strategic vision, recognizing the growing need for ethical analysis of emerging medical technologies. His "passionate, integrating intellect" was crucial to creating an interdisciplinary home for the nascent field [25].

Under Hellegers' leadership, the KIE quickly became a central hub for bioethics scholarship and education. The Institute established the first bioethics library, which evolved into the world-renowned Bioethics Research Library, and launched key publications including the Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal [25]. Hellegers recognized that for bioethics to have practical impact, it required dedicated institutional spaces where scholars from different disciplines could collaborate on pressing ethical questions in medicine and the life sciences.

Shaping the Early Bioethics Agenda

Hellegers significantly influenced the early direction of bioethics through strategic collaborations and funding initiatives. He facilitated Paul Ramsey's immersion in clinical settings by arranging for the theologian to serve as Visiting Professor of Genetic Ethics at Georgetown with support from the Joseph P. Kennedy Foundation during the spring semesters of 1968 and 1969 [21] [26]. This innovative approach gave Ramsey direct exposure to the ethical challenges faced by clinicians and researchers, informing the development of his landmark work The Patient as Person.

Hellegers' vision for bioethics differed from Potter's more expansive planetary concerns, focusing instead on the immediate ethical dilemmas created by advances in medical technology and practice. This clinically-oriented approach would become dominant in American bioethics, particularly as the field gained traction in academic medical centers and research institutions. The KIE under Hellegers' leadership helped establish the pattern of bioethics as a field intimately connected with medical practice and policy development, a legacy that continues through the institute's ongoing work in research, education, and public engagement [25].

Paul Ramsey: Forging the Conceptual Framework for Medical Ethics

Groundbreaking Publications and Methodological Innovations

Paul Ramsey, a Protestant theologian and the Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University, delivered the seminal Lyman Beecher Lectures at Yale University in April 1969—a year before Potter's first publication using the term "bioethics" [21] [26]. These lectures, published in 1970 as The Patient as Person: Explorations in Medical Ethics, have been rightly described as "the founding preaching and scriptures of the field of bioethics" [21]. At a time when ethical discussions of medical technologies occurred mainly in "obscure scientific gatherings," Ramsey provided the first systematic, comprehensive framework for addressing these issues [21].

Ramsey's methodology was characterized by several innovative approaches. First, he insisted on grounding ethical analysis in clinical reality. Prior to his lectures, he spent significant time at Georgetown University Medical Center alongside internists, transplant surgeons, obstetricians, and geneticists, observing their work and discussing moral aspects of their practice [21]. This immersion enabled him to address ethical questions with unusual specificity and relevance to actual medical dilemmas. Second, Ramsey developed a principle-based framework rooted in the Judeo-Christian concept of covenant, which he described as exploring "the meaning of care, to find the actions and abstentions that come from adherence to covenant, to ask the meaning of the sanctity of life" [26]. Though the theological foundations sometimes receded in his published work, the emphasis on fidelity and care remained central to his approach.

Core Doctrinal Contributions and Lasting Impact

Ramsey's lectures and subsequent book addressed then-emerging ethical questions that would define the early bioethics agenda, including: defining death, caring for the dying, organ transplantation, and research with human subjects [21]. His analysis of informed consent as a "canon of loyalty" in medical experimentation represented a significant advancement beyond legal formulations, grounding the requirement for consent in fundamental principles of fidelity and respect for persons [26]. This approach influenced later formulations in the Belmont Report and established consent as a central concern in research ethics.

Ramsey's work established several enduring features of mainstream bioethics. First, he demonstrated that complex medical ethical issues could be addressed through systematic ethical analysis rather than ad hoc responses. Second, his approach, while theologically grounded, was presented in terms accessible to professionals from various backgrounds, establishing the interdisciplinary nature of bioethics. Third, he focused on the patient-physician relationship as a primary locus of ethical concern, emphasizing concepts of covenant, fidelity, and the sanctity of life that would inform subsequent secular principles of respect for persons [21] [26]. Albert Jonsen notes that if Ramsey examined bioethics today, "he would be dismayed to see that it remains conflicted about its ethical foundations" and "would decry the wavering about principle and cases," particularly the field's predominant focus on autonomy at the expense of other principles [21].

Diagram: Conceptual Relationships Among Bioethics Founders

Comparative Analysis: Integration and Tension in Foundational Approaches

Methodological Frameworks and Disciplinary Orientations

The three founders represented distinct methodological approaches that continue to influence bioethics. Potter's methodology was ecological and future-oriented, emphasizing humanity's place within broader biological systems and the long-term consequences of technological development. His approach might be characterized as "macro-bioethics," concerned with planetary health and survival across generations. By contrast, Hellegers embodied a pragmatic institutional approach, focused on creating structures that would enable interdisciplinary collaboration and address immediate ethical challenges in medicine and research. Ramsey developed a principled conceptual framework grounded in theological ethics but applied to concrete clinical dilemmas, establishing what would become "micro-bioethics" focused on individual relationships and specific cases.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Foundational Methodologies

| Dimension | Van Rensselaer Potter | Andre Hellegers | Paul Ramsey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Discipline | Biochemistry, Oncology | Obstetrics, Fetal Physiology | Theological Ethics |

| Methodological Approach | Holistic, Ecological, Future-oriented | Pragmatic, Institutional, Clinical | Conceptual, Principled, Case-based |

| Scope of Concern | Global survival, Environmental ethics | Medical technology, Research ethics | Patient care, Clinical research |

| Key Institutional Role | Conceptual founder, Coined terminology | Institutional founder, Built infrastructure | Intellectual founder, Established framework |

The Institutionalization Process and Lasting Tensions

The integration of these approaches through the institutionalization of bioethics created enduring tensions within the field. Potter's disappointment that bioethics became predominantly associated with medical ethics reflected a fundamental divergence in how the field's scope was conceptualized [22] [23]. The institutional model advanced by Hellegers, while crucial for establishing bioethics as a recognized field, inevitably privileged certain types of questions—particularly those arising in clinical and research settings—over Potter's broader environmental concerns. This tension between global bioethics and medical bioethics continues to shape debates about the field's priorities and identity [23] [24].

Similarly, Ramsey's grounding in theological ethics contrasted with the increasingly secular, principle-based approach that would come to dominate mainstream bioethics, particularly after Beauchamp and Childress's Principles of Biomedical Ethics (1979) established the famous four principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice [23] [18]. The transition from Ramsey's covenant-based framework to a primarily autonomy-focused approach represents a significant shift in the field's ethical foundations. Albert Jonsen observed that Ramsey would be "appalled to see the intricate structure of ethical argument, with its exceptionless principles, collapse into a principle of autonomy, which, as he once said, merely 'enthrones arbitrary freedom'" [21].

Table: Research Framework for Analyzing Bioethics Institutionalization

| Research Dimension | Data Sources | Analytical Approach | Historical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Development | Foundational texts, Archives (KIE), Early publications | Conceptual analysis, Historical tracing | Post-WWII medical advances, Civil rights movement |

| Institutional Formation | Institute records, Funding sources, Organizational charts | Network analysis, Institutional theory | Growing public scrutiny of medicine, Congressional hearings |

| Methodological Evolution | Journal articles, Conference proceedings, Teaching curricula | Comparative analysis, Discourse analysis | Rise of interdisciplinary studies, Technology assessment |

| Professional Identity | Biographies, Professional society records, Oral histories | Ethnographic methods, Prosopography | Academic professionalization, Ethics consultation services |

The foundational contributions of Potter, Hellegers, and Ramsey established bioethics as both an intellectual discipline and an institutional practice within American medicine and research. Their diverse backgrounds and approaches created a rich foundation for a field that continues to grapple with fundamental questions about its scope, methods, and priorities. Potter's original vision of a globally-oriented bioethics concerned with environmental sustainability and human survival has gained renewed urgency in the context of climate change and global health crises [23]. Hellegers' institutional model has proven remarkably durable, with ethics institutes and programs now established throughout academic medicine. Ramsey's focus on the moral dimensions of the patient-physician relationship and his systematic approach to ethical analysis established methodological standards that continue to influence bioethics education and practice.

For contemporary researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these foundational approaches provides critical perspective on current ethical frameworks and their limitations. The tension between Potter's expansive vision and the more clinically-focused bioethics that emerged illustrates ongoing debates about how broadly the field should cast its ethical gaze. Similarly, Ramsey's concerns about the reduction of ethics to autonomy principles remain relevant in an era of personalized medicine and complex research ethics oversight. As bioethics continues to evolve in response to new technological challenges—from gene editing to artificial intelligence—the foundational insights of these three pioneers continue to offer valuable resources for navigating the ethical dimensions of scientific progress.

The field of bioethics in the United States did not emerge solely from philosophical discourse; it was profoundly shaped and institutionalized through landmark legal cases that transformed abstract ethical principles into enforceable standards. During the mid-to-late 20th century, as medical technology advanced rapidly, the traditional paternalistic model of medicine became increasingly inadequate for addressing growing concerns about patient autonomy and provider responsibility. The courts became critical arenas for defining new norms, with two cases in particular—Canterbury v. Spence and Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California—serving as pivotal moments in the legal entrenchment of bioethical principles. These cases translated the foundational ethics of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice into practical legal duties that now govern clinical practice and research. This article examines how these landmark decisions helped establish the legal architecture underlying modern bioethics, creating enduring frameworks for managing the complex ethical challenges that continue to emerge in healthcare and scientific research.

Canterbury v. Spence: The Foundation of Informed Consent

Case Background and Factual Context

In 1958, Jerry Canterbury, a 19-year-old clerk-typist, experienced severe back pain and consulted Dr. William Spence, a neurosurgeon [27]. After diagnostic procedures revealed a spinal abnormality, Dr. Spence recommended a laminectomy—surgical excision of the posterior arch of a vertebra—to correct what he suspected was a ruptured disc [27]. Canterbury consented to the procedure without significant discussion of its risks. The surgery was performed on February 11, 1959, at Washington Hospital Center [27]. Dr. Spence did not inform Canterbury or his mother of the specific risk of paralysis associated with the procedure, later testifying that communicating this risk "might deter patients from undergoing needed surgery and might produce adverse psychological reactions" [27].

Following the operation, Canterbury recuperated normally initially but suffered a fall while unattended during voiding [27]. Several hours later, he became paralyzed from the waist down and required emergency second surgery [27]. Despite further medical interventions, Canterbury sustained permanent disabilities including paralysis of the bowels, urinary incontinence, and reliance on crutches for mobility [27]. The subsequent lawsuit alleged negligence in the performance of the operation and, critically, failure to disclose the inherent risks of the procedure [27].

The Legal Shift from Physician-Centered to Patient-Centered Disclosure

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit delivered a transformative opinion that fundamentally reshaped the doctrine of informed consent [27]. Prior to Canterbury, the standard for disclosure was governed by what has become known as the "professional standard" or "physician-centered" approach, which required physicians to disclose only what a reasonable medical practitioner would disclose under similar circumstances [28]. This approach placed the medical community as the sole arbiter of what information patients should receive.

The Canterbury court explicitly rejected this physician-centered framework, declaring that "the duty to disclose does not remain the responsibility of the medical community alone" [27]. Instead, the court established what has become known as the "reasonable patient" or "material risk" standard, holding that "a risk is material when a reasonable person, in what the physician knows or should know to be the patient's position, would be likely to attach significance to the risk or cluster of risks in deciding whether or not to forego the proposed therapy" [27]. This shift transferred the focus from medical custom to patient needs for decision-making, fundamentally altering the physician-patient relationship by prioritizing patient autonomy over medical paternalism.

Methodological Framework for Determining Material Risk

The Canterbury decision established a systematic methodology for determining when a risk becomes "material" and therefore requires disclosure. The court outlined specific factors that physicians must consider when evaluating which risks to disclose:

- Nature of the Risk: The character of the risk itself and its potential impact on the patient's life [27]

- Probability of Occurrence: The statistical likelihood that the risk will materialize [27]

- Magnitude of Harm: The severity of potential injury should the risk occur [27]

- Relationship to Procedure: The directness of connection between the proposed treatment and potential harm [27]

- Alternatives: The availability and feasibility of alternative approaches [27]

- Patient-Specific Factors: Any particular circumstances of the individual patient that might affect their assessment of risks [27]

This framework created an objective standard for disclosure based on what a reasonable person would consider significant to their decision-making process, rather than deferring to medical tradition or convenience.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Informed Consent Practices

Research evaluating informed consent practices following Canterbury has employed various methodological approaches to assess comprehension, voluntariness, and disclosure adequacy:

- Structured Interviews: Utilizing standardized questionnaires to assess patient understanding of disclosed information, risks, benefits, and alternatives [27]

- Control Group Comparisons: Comparing consent processes between groups receiving standard disclosure versus enhanced disclosure protocols [27]

- Comprehension Assessment Tools: Implementing validated instruments to measure retention and understanding of key information [27]

- Observational Studies: Documenting actual consent conversations and coding for completeness of disclosure [27]

Table 1: Key Methodological Approaches for Evaluating Informed Consent

| Method Type | Primary Measures | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Interviews | Understanding of risks, benefits, alternatives | Pre- and post-consent comprehension assessment |

| Control Group Design | Differences in understanding between standard and enhanced consent | Randomized trials of consent processes |

| Observational Coding | Completeness of disclosure, patient questions, physician responses | Analysis of recorded consent conversations |

| Validated Instruments | Standardized scores of comprehension and retention | Comparison across institutions and specialties |

Tarasoff v. Regents: The Duty to Protect and Its Evolution

Case History and Factual Background

The Tarasoff case originated in 1969 when Prosenjit Poddar, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, disclosed to Dr. Lawrence Moore, a psychologist at the university's health service, his intention to kill Tatiana Tarasoff, a young woman who had rejected his romantic advances [29] [30]. Dr. Moore, concerned about this threat, notified campus police both verbally and in writing, requesting that Poddar be detained for psychiatric evaluation [29] [30]. The police briefly detained Poddar but released him after he appeared rational and promised to stay away from Tarasoff [30]. Dr. Moore's supervisor, Dr. Harvey Powelson, later directed the destruction of Moore's therapy notes and the letter to police [29]. No one warned Tarasoff or her family of Poddar's threats [29] [30].

After Tarasoff returned from a trip abroad, Poddar went to her home on October 27, 1969, and fatally stabbed her [29] [30]. Tarasoff's parents subsequently filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the university, its health service, and the therapists involved [30]. The case underwent several judicial considerations before the California Supreme Court's landmark 1976 ruling established the "duty to protect" for mental health professionals [29] [30].

From Confidentiality to Protective Action: The Legal Transformation

The California Supreme Court's decision fundamentally transformed mental health practice by establishing that the therapeutic relationship creates a special relationship that may generate a duty to protect foreseeable victims of a patient's violence [30]. The court famously declared that "the protective privilege ends where the public peril begins" [29] [30]. This ruling created an exception to therapist-patient confidentiality, prioritizing public safety in circumstances where a specific threat exists.

The court initially articulated a "duty to warn" in its 1974 opinion but modified this in the 1976 rehearing to a broader "duty to protect" [31]. This distinction proved significant, as it acknowledged that warning potential victims represents only one of several potential protective actions available to therapists. The court outlined that this duty could be fulfilled through various means, including:

- Warning the intended victim directly of the threat [31]

- Notifying law enforcement authorities [31]

- Arranging for civil commitment of the patient [31]

- Taking other reasonable steps to protect the foreseeable victim [31]

This framework acknowledged clinical discretion while establishing clear legal accountability for managing threats of violence.

Methodological Framework for Violence Risk Assessment

The Tarasoff decision necessitated the development of structured methodologies for assessing violence risk, which have evolved significantly since the original ruling. Contemporary violence risk assessment typically incorporates:

- Structured Professional Judgment (SPJ) Tools: Implementing validated instruments like the HCR-20 (Historical, Clinical, Risk Management-20) to guide systematic evaluation [31]

- Historical Factors Analysis: Reviewing past history of violence, substance use, psychopathology, and noncompliance [31]

- Dynamic Clinical Factors Assessment: Evaluating current symptoms, attitudes, and mental state [31]

- Future Risk Management Considerations: Assessing potential stressors, support systems, and responsive measures [31]

- Collateral Information Gathering: Obtaining records and reports from additional sources beyond patient self-report [31]

Table 2: Core Components of Violence Risk Assessment Post-Tarasoff

| Assessment Domain | Key Elements | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Historical Factors | Previous violence, criminal history, psychopathy traits, substance abuse history | Record review, collateral contacts |

| Clinical Presentation | Current symptoms, impulsivity, treatment compliance, violent ideation | Clinical interview, mental status exam |

| Risk Management Factors | Future stressors, support systems, treatment responsiveness, plan feasibility | Discharge planning, treatment formulation |

| Protective Factors | Social supports, treatment engagement, coping skills, environmental stability | Strength-based assessment, treatment planning |

State-by-State Legal Implementation

The Tarasoff ruling initially applied only in California, but its influence spread across the United States through various legislative and judicial pathways. Current implementation varies significantly by jurisdiction:

- Mandatory Duty States: 23 states have statutorily mandated reporting laws requiring mental health professionals to warn or protect when specific threats are made against identifiable victims [29]

- Common Law Duty States: 10 states impose a duty to warn under common law through court decisions rather than specific statutes [29]

- Permissive Duty States: 11 states allow but do not require clinicians to breach confidentiality to warn potential victims, granting discretion based on clinical judgment [29]

- No Clear Guidance: 6 states have no established position or guidance regarding the Tarasoff duty [29]

This jurisdictional variation creates important implications for mental health practice and necessitates that clinicians maintain current knowledge of their specific state requirements.

The Institutionalization of Bioethics: From Courtrooms to Clinical Practice

The Emergence of Bioethics as a Discipline

The legal principles established in Canterbury and Tarasoff emerged alongside and contributed to the broader development of bioethics as a distinct field. Prior to the 1960s, medical ethics remained largely the domain of physicians, grounded in the Hippocratic tradition and focused primarily on professional conduct and patient welfare [3] [4]. The post-World War II period witnessed unprecedented advances in medical technology and therapeutic interventions, which simultaneously created novel ethical dilemmas that traditional medical ethics frameworks proved ill-equipped to address [3] [32].

Several converging factors catalyzed the emergence of bioethics as a discipline:

- Medical Technology Advances: New capabilities in life support, organ transplantation, and critical care raised fundamental questions about quality of life, resource allocation, and the definition of death [3] [4]

- Research Ethics Abuses: Revelations concerning the Tuskegee syphilis study, Willowbrook experiments, and other ethical violations highlighted the need for stronger patient protections [3] [32]

- Consumer Rights Movement: President John F. Kennedy's 1962 Consumer Bill of Rights emphasized rights to safety, information, choice, and being heard—principles that directly influenced patient rights [3]

- Cultural Shifts Toward Autonomy: Growing emphasis on individual rights and self-determination across American society challenged medical paternalism [3] [4]

These factors created fertile ground for the establishment of dedicated bioethics institutions, most notably The Hastings Center (founded 1969) and the Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown University (founded 1971), which provided organizational homes for the systematic study of ethical issues in medicine and biology [3].

Legal Principles as Catalysts for Bioethics Infrastructure

Landmark cases like Canterbury and Tarasoff served as crucial catalysts in the development of formal bioethics infrastructure within healthcare institutions. The legal standards established in these cases necessitated systematic approaches to addressing ethical dilemmas, leading to the creation of:

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): Required for oversight of human subjects research, ensuring informed consent and risk-benefit analysis [32]

- Hospital Ethics Committees: Multidisciplinary groups providing consultation, policy development, and education on clinical ethics issues [4]

- Ethics Consultation Services: Available to patients, families, and healthcare providers for addressing specific ethical dilemmas in patient care [4]

- Patient Rights Advocates: Designated individuals or offices to protect and promote patient rights, particularly regarding informed consent [3]

This infrastructure formalized the integration of ethical analysis into healthcare delivery and research, ensuring that the principles articulated in landmark cases became operationalized in daily practice.

Diagram: Legal Foundations of Modern Bioethics Principles

The Researcher's Toolkit: Analytical Frameworks for Bioethics Integration

Essential Methodologies for Bioethics Legal Analysis

Research into the intersection of law and bioethics employs distinct methodological approaches for analyzing the impact and implementation of landmark cases: