The Belmont Report in Practice: Applying Ethical Principles to Modern Human Subjects Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Belmont Report's three core ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—and their critical application in contemporary biomedical and behavioral research.

The Belmont Report in Practice: Applying Ethical Principles to Modern Human Subjects Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Belmont Report's three core ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—and their critical application in contemporary biomedical and behavioral research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the historical foundation of these principles, offers methodological guidance for their implementation in study design and IRB protocols, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and validates their enduring relevance through comparison with other ethical frameworks and adaptation to modern research contexts like internet-mediated studies.

The Bedrock of Bioethics: Understanding the Belmont Report's History and Core Principles

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted by the United States Public Health Service (PHS) from 1932 to 1972, stands as one of the most egregious violations of human rights in the history of biomedical research [1]. This 40-year study of untreated syphilis in African American men ultimately triggered a national reckoning, leading to the National Research Act of 1974 and the creation of the Belmont Report, which established the foundational ethical principles for human subjects research in the United States [2] [3]. The journey from exploitation to ethical safeguards represents a critical evolution in scientific practice, framing a broader thesis on the indispensable role of the Belmont Report's principles. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this historical context is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for conducting ethically sound research that maintains public trust and upholds the dignity of every participant.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Methodology and Ethical Failures

Study Design and Original Protocol

Initiated in 1932, the "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male" was designed to observe the natural progression of untreated syphilis over a planned six to eight months [1] [4]. Investigators enrolled 600 impoverished African American sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama; 399 had latent syphilis, and 201 served as uninfected controls [1] [5]. The study was conceived after the retrospective "Oslo Study of Untreated Syphilis" in white males, with U.S. Public Health Service officials seeking to build a prospective study to complement it [1]. A misguided racial hypothesis underpinned the research, as physicians at the time believed syphilis affected African Americans differently than whites, with more pronounced cardiovascular effects rather than neurological impact [1].

Table 1: Tuskegee Syphilis Study Participant Demographics and Outcomes

| Category | Enrollment Figures | Long-Term Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Total Participants | 600 African American men [1] | Only 74 subjects alive at study termination in 1972 [1] |

| Syphilitic Group | 399 men with latent syphilis [1] | 28 died directly from syphilis; 100 died from related complications [1] |

| Control Group | 201 men without syphilis [1] | Outcomes not fully documented but exposed to same study procedures |

| Secondary Victims | Not enrolled | 40 wives infected; 19 children born with congenital syphilis [1] |

Research Protocol and Methodological Flaws

The study's methodology involved repeated data collection without therapeutic intent. Key procedures included:

- Deceptive Recruitment and Retention: Participants were recruited with promises of free medical care for "bad blood," a colloquial term encompassing various conditions including syphilis, anemia, and fatigue [1]. They were not informed of their syphilis diagnosis or the study's true purpose [1]. To ensure compliance with painful procedures like diagnostic lumbar punctures, researchers sent a misleading letter titled "Last Chance for Special Free Treatment" [1].

- Withheld Treatments and Active Prevention of Care: When penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis by 1947, researchers actively withheld it from participants [1]. During World War II, when 256 subjects were diagnosed with syphilis at military induction centers and ordered to obtain treatment, PHS researchers intervened to prevent them from receiving care [1]. Similarly, researchers prevented participants from accessing other venereal disease treatment campaigns that came to Macon County [1].

- Use of Placebos and Ineffective Treatments: Participants were administered disguised placebos, ineffective methods, and diagnostic procedures that were misrepresented as treatments [1]. Early in the study, some subjects received mildly effective but highly toxic compounds like salvarsan ("606"), mercurial ointments, and bismuth, but these treatments were discontinued when study funding was lost [1] [4].

Table 2: Chronology of Key Events in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study

| Year | Event | Ethical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1932 | Study begins as 6-8 month observational study [1] | Initial deception about study purpose and duration |

| 1936 | First major report published [1] | Study continues despite availability of some treatments |

| 1947 | Penicillin becomes standard syphilis treatment [1] | Critical decision to withhold effective treatment |

| 1969 | PHS committee reviews study; votes to continue [1] | Institutional failure to terminate ethically indefensible study |

| 1972 | Peter Buxtun leaks story to press; study ends [1] [4] | External whistleblower forces termination after 40 years |

Diagram 1: Tuskegee Ethical Failure Sequence

The Researcher's Toolkit: Deceptive Practices and Their Functions

Table 3: Research "Reagents" and Methodological Components in the Tuskegee Study

| Research Component | Function in Study | Ethical Concern |

|---|---|---|

| "Bad Blood" Diagnosis | Colloquial term used to obscure true nature of syphilis from participants [1] | Deliberate deception preventing informed consent |

| Lumbar Punctures | Diagnostic spinal taps presented as "special free treatment" [1] | Therapeutic misconception; painful procedure with no clinical benefit |

| Placebos (Aspirin, Supplements) | Maintain participant engagement and compliance without providing real treatment [4] | Withholding of effective treatment despite availability |

| Free Burial Insurance | Incentive to ensure families permitted autopsies [1] | Exploitation of economic vulnerability |

| Eunice Rivers, Nurse | Trusted African American intermediary to maintain participant compliance [4] | Exploitation of community trust and racial solidarity |

The Path to Reform: National Research Act and Belmont Report

Public Revelation and Political Response

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was terminated in 1972 following a leak to the press by Peter Buxtun, a former PHS social worker who had repeatedly raised ethical concerns internally before contacting journalists [1] [4]. On July 25, 1972, The Washington Star broke the story, followed by coverage in The New York Times, creating public outrage that forced the government to act [4]. In response, an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel was convened by the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs, which recommended terminating the study immediately [5]. This congressional hearing, directed by Senator Edward Kennedy, exposed the systemic ethical failures and created the political momentum for legislative action [2].

The National Research Act of 1974

The National Research Act, signed into law by President Richard Nixon on July 12, 1974, was the direct legislative response to the Tuskegee scandal [2]. The Act contained two pivotal provisions that would permanently reshape the U.S. research landscape:

- Establishment of the National Commission: The Act created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, charging it with developing guidelines for human subject research and overseeing the use of human experimentation [2].

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): The Act formalized a regulated IRB process through local institutional review boards to provide independent review of research protocols [2]. This ensured that an independent panel would evaluate studies for ethical acceptability before they could begin.

The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines

In 1979, the National Commission published the Belmont Report, which identified three fundamental ethical principles that should guide all human subjects research [3]:

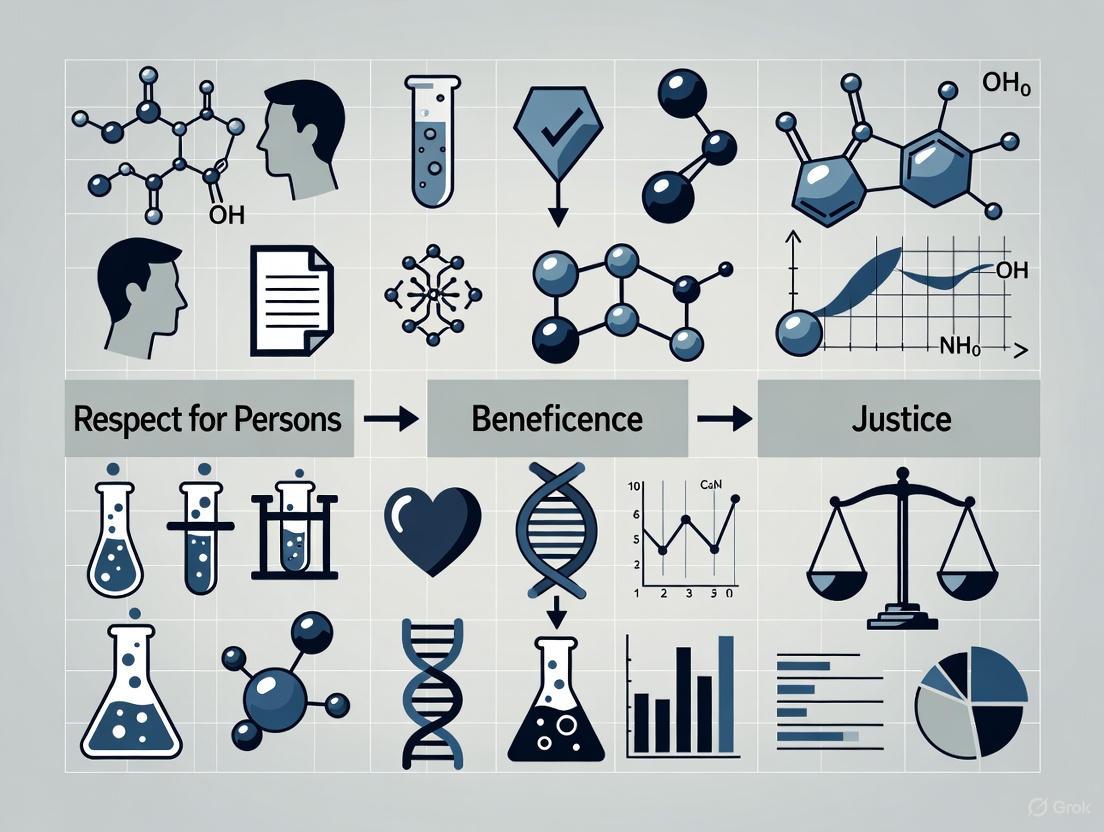

Diagram 2: Belmont Report Ethical Framework

- Respect for Persons: This principle acknowledges the dignity and autonomy of individuals and requires that subjects with diminished autonomy (such as children or those with cognitive impairments) are entitled to additional protections [3]. In practice, this principle is implemented through the process of informed consent, where participants must be given all relevant information about a study and voluntarily decide whether to enroll [6] [3].

- Beneficence: This principle describes an obligation to maximize possible benefits for society and science while minimizing possible harms to individual subjects [3]. The risk-benefit ratio must be favorable, and researchers have a continuous obligation to monitor participant welfare throughout the study [6].

- Justice: The principle of justice requires the fair distribution of both the burdens and benefits of research [3]. It addresses concerns about vulnerable populations being systematically selected for risky research while more privileged populations reap the benefits, which was starkly evident in the Tuskegee study where impoverished African American men bore all the risks with no prospect of benefit [1] [3].

Analysis: Connecting Tuskegee to Modern Ethical Protections

Direct Regulatory Responses to Tuskegee Failures

The ethical failures of the Tuskegee Study directly informed specific regulatory requirements in contemporary human subjects protections:

- Informed Consent: Tuskegee participants were deliberately deceived about their diagnosis and the study's purpose [1]. The Belmont Report's emphasis on respect for persons mandates meaningful informed consent where participants understand the research purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits [3]. Modern regulations require documentation of consent and ongoing communication of new information that might affect participation decisions [6].

- Vulnerable Populations: The exploitation of impoverished, poorly educated African American men in Tuskegee highlighted the need for special protections for vulnerable populations [1]. Current regulations require additional safeguards when research involves participants with diminished autonomy or those who may be susceptible to coercion [3].

- Justice in Subject Selection: The principle of justice directly addresses the Tuskegee legacy by requiring that the selection of subjects be scrutinized to avoid systematically recruiting vulnerable populations for risky research [3]. Researchers must ensure that the populations bearing the risks of research are positioned to enjoy its benefits [6].

Implementation in Modern Research Practice

For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, the Tuskegee-Belmont narrative translates into concrete practices:

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): The National Research Act's requirement for independent review means all research protocols must undergo scrutiny by an IRB to ensure ethical acceptability before initiation and during conduct [2] [6]. IRBs evaluate whether risks are minimized and reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, selection of subjects is equitable, and informed consent will be properly obtained [6].

- Ongoing Ethical Vigilance: The Belmont Principles recognize that ethical conflicts can emerge during research [3]. For instance, respect for persons (a child's dissent) might conflict with beneficence (potential for direct therapeutic benefit), requiring careful case-by-case analysis [3]. Researchers must maintain ethical awareness throughout the research lifecycle.

- Transparency and Accountability: Modern research requires transparency in methods, assumptions, and analyses, allowing for public scrutiny and maintaining trust [7]. Researchers must keep good records and be prepared to give an account of their decisions and actions [7].

The trajectory from the Tuskegee Syphilis Study to the National Research Act and the Belmont Report represents a profound transformation in research ethics. What began as a 40-year violation of human dignity ended by establishing a principled framework that continues to guide researchers today. The three principles of the Belmont Report—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—provide a robust structure for navigating complex ethical dilemmas in human subjects research. For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this history serves as both a cautionary tale and a compelling mandate: scientific advancement must never come at the expense of human rights and dignity. The ethical safeguards born from this dark chapter remain essential for maintaining public trust and ensuring that research continues to be a force for benefit rather than exploitation.

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was created through the National Research Act of 1974, a legislative response to profound ethical failures in research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [8] [9]. This study, which ran from 1932 to 1972, intentionally withheld treatment from African American men with syphilis without their informed consent. The public revelation of this study in 1972 sparked national outrage and created the necessary political momentum for formalizing ethical protections for research participants [9] [8]. The Commission's primary congressional charge was to identify the fundamental ethical principles that should govern research involving human subjects and to translate these principles into actionable guidelines for researchers and institutions [9] [10]. The result of this four-year effort was the Belmont Report, published in 1979, which continues to serve as the ethical foundation for human subjects research regulations in the United States [3] [9] [8].

The National Commission's Composition and Work

Commission Formation and Membership

The National Commission was composed of eleven members who represented a diverse range of expertise, including medicine, law, ethics, and the social sciences [9]. The membership included eight men and three women, with Dorothy I. Height noted as the only African American commissioner [9]. This diversity was crucial for tackling the complex ethical issues at the intersection of research, medicine, and societal values. The Commission met regularly over nearly four years, with an intensive four-day discussion period in February 1976 at the Belmont Conference Center in Maryland, from which the final report takes its name [9] [10].

Core Mandate and Key Questions

The Commission's specific mandate, as outlined in the Belmont Report itself, directed it to consider several boundary areas critical to research ethics [9] [10]:

- The distinctions between biomedical research and routine medical practice

- The role of risk-benefit assessment in determining the appropriateness of research

- Appropriate guidelines for selecting human subjects

- The nature and definition of informed consent across various research settings

Table: Key Questions in the National Commission's Mandate

| Mandate Area | Core Ethical Question |

|---|---|

| Practice vs. Research | When does an activity stop being care for an individual and start being generalizable knowledge production? |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment | What systematic approach ensures that the potential benefits of research justify the risks to participants? |

| Subject Selection | How do we select subjects fairly to avoid exploiting vulnerable populations? |

| Informed Consent | What information must be conveyed and comprehended for consent to be truly informed and voluntary? |

The Ethical Framework of the Belmont Report

The Belmont Report established three fundamental ethical principles that form an "analytical framework" for resolving ethical problems in research involving human subjects [8].

Respect for Persons

This principle incorporates two ethical convictions. First, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, capable of self-determination [11]. Second, that persons with diminished autonomy (e.g., children, individuals with cognitive impairments, prisoners) are entitled to special protections [9] [11]. The practical application of this principle is realized through the process of informed consent, which requires that prospective subjects are provided with all relevant information about the study in a comprehensible manner and that their participation is voluntary, free from coercion or undue influence [3] [9] [11].

Beneficence

This principle extends beyond the simple injunction to "do no harm" to an affirmative obligation to maximize potential benefits and minimize potential harms [8] [11]. The Belmont Report frames beneficence as an obligation, not just an aspiration. Researchers must systematically assess the risks and benefits of their proposed research, not only at the outset but throughout the conduct of the study [9] [11]. This requires a rigorous analysis to ensure that the knowledge gained is proportionate to the risks assumed by the participants.

Justice

The principle of justice addresses the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [8] [11]. It demands that the selection of research subjects be scrutinized to avoid systematically recruiting participants simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or socioeconomic status [11]. The report explicitly references the Tuskegee Syphilis Study as a gross injustice, where disadvantaged, rural African American men bore the burdens of research while the benefits of medical knowledge were available to others [9]. This principle ensures that no single group is unfairly burdened or excluded from the benefits of research.

Operationalizing the Ethical Principles

The Belmont Report does not merely state principles; it provides a framework for their application in the conduct of research. The following table outlines how each principle translates into concrete research requirements.

Table: Application of Belmont Principles in Research Practice

| Ethical Principle | Application Area | Key Requirements for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Informed Consent | • Provide all relevant information [11]• Ensure participant comprehension [9]• Guarantee voluntariness (free from coercion) [9] [11] |

| Beneficence | Risk-Benefit Assessment | • Systematically analyze risks and benefits [11]• Maximize possible benefits [8]• Minimize possible risks [8] [11] |

| Justice | Selection of Subjects | • Ensure fair selection procedures [11]• Avoid exploiting vulnerable populations [9]• Distribute burdens and benefits equitably [8] |

The Informed Consent Process

The Belmont Report details that informed consent is not a single event but a process, comprising three key elements [9]:

- Information: Researchers must disclose all information that a reasonable person would want to know to make an informed decision. This includes the research procedure, purposes, risks, benefits, and alternatives to participation [11].

- Comprehension: The information must be presented in a manner and language that is understandable to the subject. The report acknowledges that some populations require special provisions to ensure understanding [9].

- Voluntariness: The agreement to participate must be freely given, without the presence of coercion or undue influence. This is particularly relevant when researchers hold authority over potential subjects, such as in prisoner or student populations [9].

Systematic Risk-Benefit Assessment

The obligation of beneficence requires a thorough and systematic assessment of risks and benefits. This assessment must be explicit and detailed, considering the probability and magnitude of harm, as well as the potential for new knowledge and direct therapeutic benefit to the subject [11]. The Belmont Report encourages IRBs to be precise and factual in their communications with investigators regarding this assessment, moving beyond arbitrary judgments to a more rigorous analytical process [11].

Legacy and Regulatory Impact

The most direct regulatory outcome of the Belmont Report was the development and implementation of the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, known as the "Common Rule" (45 CFR Part 46) [9]. First adopted in 1991 by 15 federal departments and agencies, the Common Rule codifies the Belmont principles into enforceable regulations for all federally funded research [9]. The report also led to the strengthening of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), which are tasked with reviewing research protocols to ensure they conform to these ethical standards [9] [11]. The Belmont Report's framework provides IRB members with a method to determine if the risks of a study are justified by the potential benefits in a systematic and non-arbitrary way [11]. The report's enduring legacy is that it established a compass for ethical decision-making rather than a simple checklist, allowing its principles to adapt to new and complex ethical challenges in evolving research fields [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Ethical Research

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, implementing the Belmont principles requires specific tools and processes. The following table details key components of a modern ethical research program.

Table: Essential Components for Ethical Research Governance

| Component | Function & Purpose | Ethical Principle Served |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | An independent committee that reviews, approves, and monitors research involving human subjects to protect their rights and welfare. | Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice |

| Protocol & Informed Consent Template | Standardized documents ensuring all necessary information is presented to potential subjects in a consistent, comprehensive, and understandable format. | Respect for Persons |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment Framework | A systematic methodology for identifying, quantifying, and justifying the potential harms and benefits of a research study. | Beneficence |

| Vulnerable Population Safeguards | Additional protective procedures for groups with diminished autonomy (e.g., children, prisoners, cognitively impaired persons). | Respect for Persons, Justice |

| Equitable Recruitment Plan | A pre-defined strategy for subject recruitment that ensures fair selection and prevents the systematic targeting of vulnerable groups. | Justice |

| Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) | An independent group of experts that monitors patient safety and treatment efficacy data while a clinical trial is ongoing. | Beneficence |

| Federalwide Assurance (FWA) | A formal commitment by an institution to the U.S. government that it will comply with federal regulations for the protection of human subjects. | All Three Principles |

The Belmont Report, formally issued in 1979, established a foundational ethical framework for human subjects research in the United States [12]. It was developed by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in response to historical abuses, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and to strengthen human research protections [3] [12]. The report articulates three core ethical principles: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [12] [8]. This paper provides an in-depth examination of the principle of Respect for Persons, which embodies the ethical conviction that individuals are autonomous agents and that those with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [3] [11]. This principle is the bedrock of the informed consent process and the special protections afforded to vulnerable populations in research.

Conceptual Foundations of Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two distinct but related ethical convictions [11]. First, it affirms that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents [13]. An autonomous person is capable of self-determination; they can deliberate on personal goals and act under the direction of that deliberation [11]. The second conviction is that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to additional protections [13]. The obligation to respect autonomy requires that researchers acknowledge an individual's right to hold views, make choices, and take actions based on their personal values and beliefs [11].

The application of this principle leads to two separate moral requirements in the research context:

- The requirement to acknowledge autonomy and protect the autonomous decisions of individuals.

- The requirement to protect individuals with diminished or impaired autonomy [11].

The extent of protection required is not uniform and should be contingent upon the risk of harm and the likelihood of benefit. The judgment that an individual lacks autonomy should be periodically re-evaluated and is often situation-dependent [11].

Operationalizing Respect for Persons: The Informed Consent Process

The primary practical application of the Respect for Persons principle is the informed consent process [14]. This process is designed to ensure that subjects' participation is voluntary and that they have adequate information to make an informed decision.

Key Elements of Informed Consent

The Belmont Report specifies that informed consent must encompass three critical components: information, comprehension, and voluntariness [12].

- Information: Researchers must disclose all relevant information about the study that a reasonable person would need to make a decision [3]. The Belmont Report recommends including:

- The research procedure and its purposes.

- Any reasonably foreseeable risks and anticipated benefits.

- Alternative procedures available (particularly when the research involves therapy).

- A statement offering the subject the opportunity to ask questions and to withdraw from the research at any time without penalty [12] [11].

- Comprehension: The manner and context in which information is conveyed must ensure that the prospective subject adequately understands it [12]. This involves presenting information in a language and format that is comprehensible to the subject, avoiding technical jargon, and ensuring that the subject has the capacity to make a decision. For some subjects, this may require additional measures, such as using plain-language forms, interpreters, or staged consent processes [15].

- Voluntariness: Consent must be given voluntarily, free from coercion or undue influence [13]. Coercion occurs when an overt threat of harm is presented to secure compliance. Undue influence, often more subtle, involves offering excessive or inappropriate rewards to overcome a person's better judgment [12]. The voluntariness of a decision can be compromised by situational factors, such as power dynamics in a doctor-patient relationship or institutional hierarchies [15].

Assessment of Vulnerabilities in the Consent Process

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to assessing vulnerabilities that can impair the consent process, guiding researchers toward appropriate safeguards.

Protections for Persons with Diminished Autonomy

A critical function of the Respect for Persons principle is to mandate additional protections for individuals with diminished autonomy [13]. The Belmont Report recognizes that not all individuals are capable of self-determination and that the extent of this capacity can vary [11].

Defining and Identifying Vulnerability

Vulnerability in research is a condition, either intrinsic or situational, that puts some individuals at greater risk of being used in ethically inappropriate ways [15]. The Common Rule explicitly identifies several vulnerable categories requiring special protections: pregnant women, human fetuses, neonates, prisoners, and children [16]. However, vulnerability extends beyond these categories to include any individual with a reduced ability to protect their own interests [15]. This can include individuals with cognitive or communicative impairments, those who are economically or educationally disadvantaged, and employees or students [16].

Two primary approaches to understanding vulnerability are used:

- The Categorical Approach: This method classifies certain groups as vulnerable. While practical for regulation, it can be limiting as it does not account for individuals with multiple vulnerabilities or variations in the degree of vulnerability within a group [15].

- The Contextual Approach: This more nuanced method identifies situations in which individuals might be considered vulnerable. It recognizes that vulnerability can be fluid and dependent on specific circumstances [15]. For example, an otherwise autonomous person may become vulnerable in an emergency medical situation.

Key Vulnerability Categories and Corresponding Safeguards

Table 1: Vulnerability Categories and Safeguards for Persons with Diminished Autonomy

| Vulnerability Category | Description and Examples | Recommended Safeguards and Protections |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive/Communicative [15] | Difficulty comprehending information or making decisions. Examples: children, adults with cognitive impairment, persons speaking a different language than the researcher, individuals in acute distress (e.g., pain). | Use of plain-language consent forms; objective assessment of capacity; use of surrogates or legally authorized representatives; translated materials and interpreters; staged consent processes; delaying enrollment until transient impairment resolves [15]. |

| Institutional [15] | Persons under formal authority of others who may have different priorities. Examples: prisoners, military personnel, students. | Insulated consent procedures (e.g., having neutral parties approach potential subjects); careful scrutiny of participant selection; ensuring that refusal to participate does not affect institutional standing [15]. |

| Deferential [15] | Persons under informal authority based on power, knowledge, or social inequalities. Examples: doctor-patient relationships, gender or class-based deference. | Scrutiny of the consent process to ensure decisions are free from undue influence; ensuring the subject knows participation is voluntary and refusal will not affect care [15]. |

| Societal/Economic [17] [16] | Economically or educationally disadvantaged persons who may be susceptible to undue influence due to perceived financial or other rewards. | Ensuring that monetary payments are not coercive but function as compensation for time and burden; equitable selection of subjects so that no class bears disproportionate research burdens [17]. |

Special Considerations: The Case of Children

Research involving children exemplifies the potential for the Belmont principles to conflict and the need for careful balancing. Children, due to their developmental immaturity and legal status, cannot provide full informed consent [3]. Instead, a parent or guardian provides permission, and the child, when capable, provides assent [3]. Respect for Persons requires honoring a child's dissent when they do not want to enroll [3]. However, there are circumstances where Beneficence (the obligation to secure well-being) and Justice (fair distribution of benefits and burdens) may override a child's dissent. For instance, in greater-than-minimal risk research with potential for direct benefit to the child, an IRB may allow a parent's permission to override the child's wishes to secure that benefit [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Frameworks for Ethical Practice

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, applying the principle of Respect for Persons requires practical tools and frameworks.

Table 2: Essential Frameworks and Applications for Upholding Respect for Persons

| Tool/Framework | Primary Function | Application in Research Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent Document | To document the process of providing information and obtaining voluntary, comprehending agreement. | Serves as a checklist and record that key study information (risks, benefits, alternatives, etc.) was disclosed and understood by the subject [12]. |

| Capacity Assessment Protocol | To objectively evaluate a potential subject's ability to understand information and make a voluntary decision. | Used when a subject's decision-making capacity is in question; may involve simple questioning or standardized tools to assess understanding of the study [15]. |

| Vulnerability Screening Checklist | To systematically identify potential vulnerabilities during study design and participant recruitment. | Helps researchers proactively identify subjects who may need additional safeguards due to cognitive, institutional, deferential, or economic vulnerabilities [15]. |

| IRB Review Process | To provide independent, ethical oversight of research protocols to ensure subject protections. | The IRB scrutinizes the informed consent process, participant selection, and study design to ensure Respect for Persons is upheld, especially for vulnerable groups [3] [11]. |

| Waiver of Consent Criteria | To define the rare circumstances in which informed consent may be altered or waived. | Guides researchers and IRBs on when consent may not be required, such as for minimal risk research where seeking consent is impractical, provided privacy safeguards are in place [13]. |

The principle of Respect for Persons is a cornerstone of ethical human subjects research. It imposes a dual mandate: to honor the autonomous choices of self-determining individuals and to provide robust protection for those with diminished autonomy. For researchers and drug development professionals, this translates into a rigorous commitment to a meaningful informed consent process and a proactive duty to identify and safeguard vulnerable populations. As research contexts and capabilities continue to evolve, the foundational principles of the Belmont Report, particularly Respect for Persons, remain an essential compass for navigating ethical challenges and maintaining public trust in the research enterprise [14].

The principle of beneficence forms a cornerstone of ethical research involving human subjects, establishing a fundamental obligation for researchers to maximize potential benefits while minimizing possible harms. This principle, first formally articulated in the Belmont Report of 1979, provides the ethical foundation for modern research regulations and practices [3]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and implementing beneficence extends beyond regulatory compliance—it represents a core professional responsibility to protect research participants while advancing scientific knowledge. The Belmont Report defines beneficence as an obligation to protect subjects from harm by maximizing possible benefits and minimizing possible harms, creating a dual mandate that requires careful balancing throughout the research lifecycle [3]. This technical guide explores the practical application of this principle, providing methodologies, analytical frameworks, and implementation tools to systematically integrate beneficence into research design and execution.

Theoretical Foundations: Beneficence Within the Belmont Framework

The Belmont Report established three fundamental principles guiding human subjects research: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice [3] [18]. These principles emerged in response to historical ethical failures and provide the framework for contemporary research ethics. Beneficence specifically addresses the researcher's obligation to ensure participant well-being through a systematic process of risk-benefit assessment [3]. This principle transcends the simple medical maxim "do no harm" to incorporate active efforts to maximize potential benefits [19]. In practice, beneficence requires that researchers thoroughly assess and justify risks, ensure risks are minimized, and confirm that the potential benefits outweigh these risks [3]. The application of beneficence often requires balancing against other ethical principles, particularly when working with vulnerable populations or in contexts where immediate benefits to participants may be limited [3].

The Nuremberg Code and Declaration of Helsinki provide important historical context for the development of beneficence as a research principle [18]. These foundational documents emphasize that research must yield fruitful results for the good of society, unattainable by other methods, and that risks should not exceed humanitarian importance [18]. The Belmont Report built upon these foundations to establish the comprehensive risk-benefit analysis framework that guides modern research ethics.

Methodological Framework: Implementing Beneficence in Research Design

Systematic Risk-Benefit Assessment Protocol

Implementing beneficence requires a structured methodology for identifying, quantifying, and balancing potential benefits and harms. The following systematic protocol ensures comprehensive assessment:

Risk Identification and Categorization: Conduct a thorough review of all potential physical, psychological, social, and economic harms. Categorize risks as minimal, minor, moderate, or severe based on probability, magnitude, and duration. This process should involve literature review, expert consultation, and preliminary studies where appropriate [20] [3].

Benefit Maximization Strategy: Identify all potential direct benefits to participants and collateral benefits to society. Develop explicit strategies to enhance these benefits through optimal study design, participant selection, and ancillary care provisions. The principle of beneficence requires not merely avoiding harm but actively promoting well-being [19].

Risk Minimization Engineering: Implement methodological safeguards to reduce the probability and severity of identified risks. This includes appropriate exclusion criteria, data monitoring procedures, safety endpoints, and stopping rules. The Belmont Report emphasizes that researchers must take all necessary steps to prevent harm, including physical, emotional, or psychological harm [20].

Equitable Benefit Distribution: Ensure that the populations bearing research risks stand to benefit from the knowledge gained, addressing the intersection of beneficence and justice [3]. This requires careful consideration of participant selection and post-trial access to interventions.

Quantitative Methodologies for Within-Subjects Benefit-Risk Analysis

Within-subjects designs provide powerful methodological approaches for measuring intervention effects while minimizing participant risks. The following quantitative methodologies enable precise benefit-risk assessment:

Paired Difference Analysis: When each participant provides both experimental and control observations (through baseline measurements or crossover designs), compute within-individual differences to quantify intervention effects while controlling for between-subject variability [21]. The appropriate numerical summary involves calculating the mean of these differences across all participants, not by subtracting summary statistics between groups [21].

Case-Profile Plot Methodology: For studies with multiple longitudinal measurements per participant, employ case-profile plots to visualize individual trajectories of benefit and harm indicators [21]. This graphical approach reveals patterns that might be obscured in group-level analyses and helps identify participants who may be experiencing disproportionate harms or benefits.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of IgE Reduction Intervention [21]

| Measurement Point | Mean (μg/L) | Standard Deviation (μg/L) | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before Intervention | 1690.5 | 1615.53 | 11 |

| After Intervention | 1387.4 | 1354.28 | 11 |

| Reduction | 303.2 | 325.28 | 11 |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates how within-subjects analysis can quantify benefits while using participants as their own controls, potentially reducing the sample size needed to detect significant effects and thereby minimizing overall research risks [21].

Multi-Timepoint Benefit-Risk Tracking: For studies with more than two measurement points, calculate changes from baseline for each subsequent assessment to track the evolution of benefits and risks over time [21]. This approach is particularly valuable in dose-escalation studies or when investigating delayed treatment effects.

Table 2: Pain Threshold Changes Following Therapeutic Intervention [21]

| Measurement Time | Mean (kPa) | Std Dev (kPa) | Sample Size | Mean Increase from Baseline | SD Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre: 5 minutes | 446.5 | 175.18 | 16 | - | - |

| Post: 5 minutes | 479.6 | 199.61 | 16 | 33.1 | 73.93 |

| Post: 15-20 minutes | 506.9 | 214.36 | 16 | 60.4 | 102.72 |

Table 2 illustrates how benefit accumulation can be tracked over time, providing crucial data for evaluating whether increasing benefits justify continuing exposure to research risks [21].

Analytical Tools: Visualization and Decision-Support Frameworks

Beneficence Implementation Workflow

Risk-Benefit Analysis Matrix

Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Ethical Implementation

| Item/Category | Function in Ethical Research | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Assessment Tools | Precisely measure benefits and harms using reliable instruments | Standardized quality of life measures, psychological distress scales, and physiological monitoring devices |

| Data Monitoring Systems | Continuous safety surveillance during study conduct | Electronic data capture with automated adverse event alerts and scheduled interim analyses |

| Confidentiality Protection Tools | Safeguard participant privacy and data security | Encryption software, secure storage solutions, and data anonymization protocols [20] |

| Informed Consent Documentation | Ensure comprehensive participant understanding | Multi-format consent materials (written, visual, interactive) with comprehension assessment [3] [22] |

| Unblinding Procedures | Emergency access to treatment assignment when clinically indicated | Secure, 24/7 accessible unblinding system with documentation protocols |

Advanced Applications: Beneficence in Complex Research Scenarios

Benefit Enhancement in Novel Therapeutic Contexts

Recent ethical scholarship has proposed expanding the beneficence framework beyond harm reduction to incorporate benefit enhancement strategies, particularly in novel therapeutic contexts such as psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy [19]. This approach acknowledges that some interventions may offer substantial benefits when used in supportive settings, and ethical practice requires not merely minimizing potential harms but actively facilitating positive outcomes [19]. In psychedelic research, this involves creating optimal set and setting, providing psychological support, and integrating experiences to maximize therapeutic benefits [19]. This expanded beneficence model maintains harm reduction as essential while adding positive obligation to enhance potential benefits through methodological optimization.

Ethical Conflict Resolution Framework

The principle of beneficence may sometimes conflict with other ethical principles, particularly respect for persons, requiring a structured approach to resolution [3]. In pediatric research, for example, a child's dissent (respect for persons) may conflict with potential therapeutic benefit (beneficence) [3]. The ethical framework suggests that:

- When research offers direct therapeutic benefit and exceeds minimal risk, beneficence may sometimes outweigh a child's dissent, particularly when the benefit is significant [3].

- When research offers no direct benefit but generates vital knowledge for others with the same condition (justice), additional safeguards are required, such as two-parent permission [3].

- In all cases, researchers should make every effort to resolve conflicts through compromise and respect for participant perspectives [3].

The principle of beneficence requires ongoing vigilance throughout the entire research process, from initial design to post-study follow-up. By implementing the systematic methodologies, analytical frameworks, and practical tools outlined in this technical guide, researchers can fulfill their ethical obligation to maximize potential benefits while minimizing possible harms. The frameworks presented enable quantitative assessment of risk-benefit ratios, structured approaches to ethical challenges, and practical strategies for enhancing research outcomes. As scientific methodologies advance and new research contexts emerge, the foundational principle of beneficence remains essential for maintaining public trust and ensuring that research continues to serve humanitarian ends while protecting those who make knowledge advancement possible.

The principle of Justice constitutes one of three core ethical tenets outlined in the 1979 Belmont Report, a foundational document for protecting human subjects in research. This principle specifically addresses the timeless and weighty question of "Who ought to receive the benefits of research and bear its burdens?" [23]. Justice requires a fair distribution of both research advantages and disadvantages across society, ensuring that no single group is systematically overburdened or excluded from benefits [24] [25]. This ethical mandate serves as a crucial safeguard against the exploitation of vulnerable populations and promotes equity in the selection of research subjects and the allocation of research-derived benefits.

The historical significance of this principle is rooted in egregious ethical violations witnessed in studies like the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, where the burdens of research were imposed exclusively upon African American males while benefits were withheld, even after effective treatment became available [23]. Such historical precedents established a persistent distrust of research institutions among minority communities and underscored the critical necessity for distributive justice in research ethics [23]. In contemporary contexts, from COVID-19 clinical trials to behavioral intervention studies, the operationalization of justice remains equally vital for ethical research conduct [26] [23].

Theoretical Framework of Distributive Justice

Conceptual Foundations

The principle of justice encompasses fair treatment of human subjects across multiple domains, including equitable distribution of research risks and benefits, representative subject pools, and appropriate recruitment practices [23]. This distributive dimension focuses on the formulations of justice, which include:

- To each person an equal share

- To each person according to individual need

- To each person according to individual effort

- To each person according to societal contribution

- To each person according to merit [23]

These formulations provide a framework for evaluating whether the selection of research subjects is systematically biased toward groups for reasons of manipulability, vulnerability, or convenience rather than for reasons directly related to the research problem [23].

Core Components of Justice in Research

Table 1: Key Aspects of the Principle of Justice

| Component | Ethical Requirement | Historical Violation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Burden Distribution | Research burdens should not fall disproportionately on any particular group | Tuskegee syphilis study imposed burdens exclusively on African American men [23] |

| Benefit Distribution | Benefits should be accessible to those who bear burdens, including future access to interventions | Participants in Tuskegee study were denied effective treatment when it became available [23] |

| Subject Selection | Selection should be based on scientific objectives, not convenience or manipulability | Vulnerable populations selected due to limited autonomy rather than scientific relevance [23] |

| Recruitment Practices | Procedures must be fair and avoid exploitation of vulnerable circumstances | Recruitment exploited participants' limited access to healthcare and financial constraints [23] |

Quantitative Assessment of Equity in Research

Metrics for Evaluating Distributive Justice

The assessment of justice in research requires both qualitative evaluation and quantitative measurement. Key metrics for evaluating equity include participant demographic data compared to disease prevalence rates, economic analyses of benefit distribution, and comparative burden assessments across population subgroups.

Table 2: Quantitative Measures for Assessing Research Equity

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Representation | Disparity ratios between disease burden and trial participation; Percentage of underrepresented groups in trials | African American and Hispanic/Latinx patients substantially underrepresented in clinical trials despite COVID-19 disproportionately affecting these groups [26] |

| Geographic Distribution | Number of trial sites in low/middle-income countries (LMICs) versus high-income countries; Applicability of research findings across regions | WHO Solidarity Trial included only a few sites in Africa, Latin America, and South/Southeast Asia, limiting local applicability of results [26] |

| Benefit Accessibility | Patent barriers; Pricing structures; Post-trial access provisions | Patent protections enabling high monopoly prices effectively block portions of global population from accessing developed products [26] |

| Burden Compensation | Analysis of compensation adequacy relative to participant time, risk, and inconvenience; Barrier mitigation effectiveness | Travel vouchers and extended hours to mitigate participation barriers for underserved communities [23] |

Data Visualization for Equity Assessment

Effective visualization of equity data enables researchers to identify disparities and monitor progress toward justice goals. The following diagrams illustrate essential workflows and relationships for implementing and evaluating justice in research.

Equity Implementation Workflow

Barriers and Mitigation Strategies

Experimental Protocols for Equitable Research

Protocol 1: Inclusive Participant Recruitment

Objective: Ensure participant enrollment reflects the demographic distribution of the disease population.

Methodology:

- Disease Burden Analysis: Conduct comprehensive review of epidemiological data to identify populations disproportionately affected by the target condition [26].

- Recruitment Strategy Design: Implement multi-faceted recruitment incorporating:

- Barrier Mitigation: Implement practical accommodations including:

- Monitoring and Adjustment: Continuously track enrollment demographics against predetermined targets and modify strategies as needed to address disparities [26].

Validation Metrics:

- Percentage of enrolled participants from underrepresented groups relative to disease prevalence

- Recruitment yield by strategy and demographic group

- Participant retention rates across demographic segments

Protocol 2: Equitable Global Trial Design

Objective: Ensure clinical trials generate globally applicable knowledge while avoiding exploitation of resource-limited settings.

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Identify trial locations based on disease relevance rather solely on regulatory convenience or participant manipulability [26].

- Local Capacity Building: Incorporate plans for strengthening local research infrastructure and expertise.

- Contextual Adaptation: Modify intervention protocols to account for local healthcare infrastructures, genetic differences, and comorbidity prevalence [26].

- Access Planning: Develop pre-trial strategies for ensuring successful interventions become accessible to host communities post-trial [26].

Validation Metrics:

- Number of trial sites in LMICs relative to global disease burden

- Percentage of interventions developed through research that remain accessible to host communities

- Measurement of local research capacity enhancement

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Justice-Oriented Research

| Tool Category | Specific Resources | Function in Promoting Justice |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment Materials | Culturally adapted informed consent documents; Multilingual recruitment materials; Health literacy-appropriate educational resources | Ensures comprehension and authentic informed consent across diverse populations, including those with limited English proficiency or lower health literacy [26] |

| Community Engagement Resources | Community advisory board frameworks; Partnership development guidelines; Trust-building consultation protocols | Facilitates meaningful collaboration with affected communities, building trust and ensuring research relevance to community needs [23] |

| Barrier Mitigation Tools | Transportation voucher systems; Flexible scheduling software; Childcare coordination services; Mobile research units | Reduces practical barriers to participation for working individuals, those with limited transportation, and caregivers [23] |

| Data Equity Instruments | Demographic data collection standards; Disparity assessment metrics; Equity monitoring dashboards | Enables continuous monitoring of recruitment equity and identification of disparities requiring intervention [26] |

| Access Enforcement Mechanisms | Patent pooling agreements; Affordable pricing frameworks; Technology transfer protocols | Ensures beneficial research outcomes remain accessible to communities that participated in and contributed to the research [26] |

Case Study: Justice in COVID-19 Research

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a compelling test case for the application of justice principles in global health research. Several critical equity challenges emerged that highlight both violations of and adherence to justice principles.

The geographic distribution of clinical trials raised significant justice concerns. Early in the pandemic, statements suggesting that COVID-19 trials should be conducted in Africa to take advantage of weaker healthcare infrastructure were rightly condemned as reflecting a "colonial mentality" [26]. Conversely, the exclusion of LMICs from major trials like the WHO Solidarity Trial, which included only a few sites in Africa, Latin America, and South/Southeast Asia, created a different justice problem by limiting the applicability of research findings to these regions [26].

The recruitment disparities in COVID-19 trials within the United States further illustrated justice challenges. Despite African American and Hispanic/Latinx patients experiencing disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection and mortality, these groups remained substantially underrepresented among clinical trial participants [26]. This representation disparity threatens the generalizability of trial findings and violates the justice principle that those bearing disease burdens should have access to potential research benefits.

Promisingly, the pandemic also witnessed innovative approaches to promoting justice. Some education researchers chose to make evidence-based online educational curricula available to all schools in need rather than just partner research schools [23]. Additionally, significant efforts emerged to establish patent pooling mechanisms for COVID-19 products, making technologies more accessible to generic manufacturers who could produce them at affordable prices [26].

Implementation Framework for Research Institutions

Institutional Review Board Guidelines

IRBs play a critical role in enforcing the principle of justice through rigorous protocol review. Key considerations for IRBs include:

- Scrutiny of Subject Selection: IRBs must ensure research subjects are not selected systematically because of "their manipulability, susceptibility to coercion, or convenience for researchers" [23]. Instead, populations should be selected based on characteristics directly related to the research questions.

- Benefit-Risk Analysis: IRBs must evaluate whether the benefits of study participation are commensurate with the burdens participants will experience [23]. This is particularly crucial for studies involving populations with nuanced vulnerabilities.

- Accessibility Review: IRBs should assess whether researchers have implemented adequate accommodations to ensure all qualified individuals have realistic access to participation opportunities [23].

Researcher Accountability Measures

Individual researchers bear responsibility for implementing justice principles throughout the research lifecycle:

- Pre-Study Equity Assessment: Conduct formal analysis of how recruitment plans align with disease burden demographics before protocol finalization.

- Community Consultation: Engage representatives from affected communities during study design to identify potential barriers and concerns.

- Continuous Monitoring: Track recruitment and retention metrics by demographic group throughout study conduct.

- Post-Study Benefit Planning: Develop explicit plans for ensuring successful interventions become accessible to participant communities.

The principle of justice requires ongoing commitment throughout the research process—from initial study design through post-trial access. For researchers working with groups with nuanced vulnerability, this is especially important due to histories of exploitation and neglect [23]. The ethical imperative extends beyond mere compliance with IRB requirements to embrace a proactive stance toward identifying and eliminating structural barriers to equitable participation.

Successful implementation of justice principles requires researchers to approach their work with cultural sensitivity, structural competence, and collaborative ethos [23]. By introducing elements of flexibility and cooperation within research designs, investigators can ensure they are not withholding benefits from marginalized communities while simultaneously enhancing the scientific validity and generalizability of their findings. Through such comprehensive integration of justice considerations, the research community can fulfill the ethical mandate for equitable distribution of research benefits and burdens.

This technical guide examines the definitive pathway through which the Belmont Report's ethical principles became codified into the U.S. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, known as the Common Rule (45 CFR 46). Framed within a broader thesis on the enduring role of the Belmont Report in human subjects research, this paper provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed analysis of this regulatory evolution. We explore the historical catalysts for the Belmont Report, deconstruct its three core ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—and detail the mechanisms of their translation into enforceable regulations. The document includes structured data presentations, analytical frameworks for ethical review, and practical tools for navigating modern compliance requirements, underscoring the continued relevance of this foundational ethical framework in contemporary research.

The creation of the Belmont Report was a direct response to grave ethical failures in human subjects research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1972), during which hundreds of African American men were denied treatment for syphilis without their knowledge or consent [27] [12]. Public disclosure of this study prompted the U.S. Congress to pass the National Research Act of 1974, which led to the establishment of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [9] [12]. This Commission was charged with identifying the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of research involving human subjects.

The Commission deliberated for four years, including a pivotal four-day meeting at the Belmont Conference Center in Maryland in February 1976, which gave the report its name [9] [28]. The final Belmont Report was published in 1979 [9]. Its primary achievement was the articulation of three comprehensive, unifying ethical principles to guide the conduct of human subjects research. While the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki provided earlier ethical foundations, the Belmont Report was distinctive in its aim to provide a more flexible framework applicable to a wide range of research disciplines [28] [12].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones Leading to the Common Rule

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code | Established the absolute necessity of voluntary consent after the Nazi war crimes trials [28]. |

| 1964 | Declaration of Helsinki | Distinguished therapeutic from non-therapeutic research and emphasized beneficence [28]. |

| 1974 | National Research Act | Created the National Commission and mandated the establishment of IRBs [9] [12]. |

| 1978/1979 | Belmont Report Published | Articulated the three core principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [11] [9]. |

| 1981 | HHS Issues 45 CFR 46 | Department of Health and Human Services codified regulations based on Belmont principles [12]. |

| 1991 | Federal Policy (Common Rule) Adopted | 14 other federal agencies adopted a uniform set of rules identical to HHS regulations [9] [12]. |

| 2019 | Revised Common Rule Effective | Updated the regulations to address modern research contexts while retaining Belmont principles [29]. |

The Foundational Ethical Principles of the Belmont Report

The moral framework of the Belmont Report is built upon three ethical principles, which are stated as "comprehensive general prescriptive judgements" relevant to all research involving human subjects [11] [12].

Respect for Persons

This principle incorporates two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to special protections [11]. An autonomous agent is an individual capable of deliberating about personal goals and acting under that deliberation. The application of this principle leads to the requirement that subjects must voluntarily participate in research and must be provided with adequate information to make an informed decision. This ensures the research participation is based on their own understanding and free will, free from coercion or undue influence [11] [9]. For individuals with diminished autonomy—such as children, prisoners, or those with cognitive disabilities—this principle requires seeking permission from authorized surrogates and affording additional safeguards to protect their well-being [12].

Beneficence

This principle extends beyond the simple injunction to "do no harm" to a positive obligation to maximize potential benefits and minimize potential risks [11] [28]. The principle of beneficence requires a systematic assessment of risks and benefits associated with the research. The Belmont Report stresses that "brutal or inhumane treatment of human subjects is never morally justified" and that risks must be reduced to those necessary to achieve the research objective [12]. Investigators are obligated to ensure the research design is sound, that they are qualified to perform the procedures, and that the gathered knowledge justifies any inherent risks to the subjects. The benefits and risks must be carefully balanced, and the resulting risk-benefit ratio must be favorable [11].

Justice

The principle of justice requires the fair distribution of the burdens and benefits of research [11]. It addresses the question of which persons or classes of persons ought to bear the risks of research, and which should reap its rewards. The Belmont Report explicitly condemns the selection of subjects based on convenience, compromised position, or societal biases (e.g., racial, sexual, economic) [11] [12]. This principle was formulated in direct response to historical abuses where economically disadvantaged, socially marginalized, or institutionalized individuals were systematically selected for high-risk research. Justice demands that research subjects not be drawn disproportionately from groups unlikely to benefit from the subsequent applications of the research [9] [12].

The Regulatory Pathway: From Ethical Principles to Enforceable Rule

The transformation of the Belmont Report's ethical principles into the binding regulations of the Common Rule was a deliberate, multi-stage process. The following diagram illustrates this regulatory pathway and the key applications that bridge ethical principles with regulatory requirements.

The diagram above shows how historical events led to legislative action, which commissioned the ethical framework of the Belmont Report. The report's three principles were then operationalized through specific applications, which directly informed the creation of the HHS regulations and, ultimately, the multi-agency Common Rule.

The Common Rule as the Operationalization of Belmont

The Common Rule is the informal term for the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, which was unified across multiple federal departments and agencies in 1991 [12]. For the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Common Rule is codified at 45 CFR Part 46, with Subpart A representing the core policy [12] [30]. The Rule legally mandates requirements for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), informed consent, and assurance of compliance for all federally funded research [31].

The Common Rule directly embeds the principles of the Belmont Report. The Code of Federal Regulations explicitly states that department or agency heads retain final judgment on coverage and "this judgment shall be exercised consistent with the ethical principles of the Belmont Report" [29]. Furthermore, the authority to waive certain procedural requirements is contingent upon the alternative procedures being "consistent with the principles of the Belmont Report" [29].

Table 2: Mapping Belmont Report Principles to Common Rule Requirements

| Belmont Report Element | Operational Application | Common Rule (45 CFR 46) Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Informed Consent [11] | Detailed requirements for consent document content and process (§46.116), criteria for waiver of consent (§46.117) [31] [27]. |

| Beneficence | Assessment of Risks and Benefits [11] | IRB criteria for approval include risks minimized and justified by anticipated benefits (§46.111) [11] [31]. |

| Justice | Selection of Subjects is Equitable [11] | IRB must ensure subject selection is equitable (§46.111) [11]. Vulnerable populations get additional protections in Subparts B, C, and D [32] [12]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Applying Belmont Principles in Practice

For the research professional, understanding the interplay between the Belmont Report and the Common Rule is essential for designing and conducting ethically sound and compliant research. The following diagram and table provide a practical framework for navigating this process.

Key Research Reagent Solutions: Ethical and Regulatory Components

For a researcher, the following components are as essential as any laboratory reagent for successfully conducting human subjects research.

Table 3: Essential Components for Human Subjects Research

| Component | Function & Purpose | Belmont Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | An independent ethics committee that reviews, approves, and monitors research protocols to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects [31]. | All Three |

| Informed Consent Document | A process and document that ensures prospective subjects understand the research risks, benefits, and alternatives, allowing for a voluntary decision to participate [11] [27]. | Respect for Persons |

| Protocol Risk-Benefit Analysis | A systematic assessment within the research protocol that justifies the risks to subjects by the anticipated benefits to them or to society [11] [12]. | Beneficence |

| Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Scientifically justified criteria for subject selection that ensure equitable distribution of the burdens and benefits of research, avoiding exploitation of vulnerable groups [11]. | Justice |

| Single IRB (sIRB) of Record | For multi-site research, a designated single IRB that conducts the review for all sites, streamlining the process while maintaining protections [31]. | Beneficence, Justice |

| Data Use/Sharing Agreement | A governance document specifying how participant data will be used, shared, and protected, especially for de-identified data or biospecimens [27]. | Respect for Persons |

Experimental Protocol for Ethical Review

The following methodology outlines the standard operational procedure for securing approval for human subjects research, reflecting the application of Belmont principles through the Common Rule's regulatory mechanisms.

Protocol Development: The investigator designs a research protocol that incorporates ethical considerations from the outset. This includes:

- Designing a robust informed consent process with a document written in language understandable to the prospective subject [11].

- Conducting a preliminary risk-benefit analysis and implementing design features to minimize risks [11] [12].

- Defining inclusion/exclusion criteria that are equitable and scientifically sound [11].

IRB Submission & Review: The investigator submits the complete protocol, consent documents, and supporting materials to their institution's IRB. The IRB then conducts a review, which can be full board, expedited, or a determination that the research is exempt, based on the level of risk presented [31].

- The IRB evaluates the protocol against the criteria of 45 CFR 46.111, ensuring risks are minimized and reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, subject selection is equitable, and informed consent will be properly sought and documented [31].

IRB Approval & Implementation: Upon approval, the investigator may begin subject recruitment and enrollment. All activities must conform to the approved protocol. The consent process must be followed meticulously, and any proposed changes to the research must receive further IRB review and approval before implementation [33].

Ongoing Compliance and Reporting: The investigator is responsible for maintaining ongoing compliance. This includes:

The pathway from the Belmont Report to the Common Rule represents a seminal achievement in research ethics, successfully translating a foundational ethical framework into a durable and enforceable regulatory system. For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, an in-depth understanding of this relationship is not merely a matter of regulatory compliance but a cornerstone of rigorous and responsible science. The three principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice continue to provide the essential moral compass for navigating the complex ethical challenges inherent in human subjects research. As the regulatory landscape evolves, as seen in the 2018 revisions to the Common Rule and ongoing policy updates from agencies like the NSF [31] [33], the bedrock principles of the Belmont Report remain the constant foundation upon which the protection of human subjects is built.

From Theory to Protocol: Operationalizing Belmont Principles in Study Design and IRB Submissions

The principle of Respect for Persons, as articulated in the 1979 Belmont Report, forms the ethical bedrock for the requirement of informed consent in human subjects research [3]. This principle acknowledges the autonomy of individuals and obligates researchers to treat them as autonomous agents capable of making their own decisions [34]. For persons with diminished autonomy, it necessitates additional protections [8]. The practical application of this principle is the informed consent process—a comprehensive educational interaction that empowers prospective participants to make a voluntary, informed decision about their involvement in research [35]. This guide details the implementation of a meaningful consent process that transcends regulatory compliance, fulfilling the ethical duty of Respect for Persons.

Core Components of a Meaningful Consent Process

A meaningful consent process is not a single event but a continuous, dynamic interaction. It is built upon three foundational pillars, as derived from the Belmont Report's applications section on informed consent [9].

Information Disclosure

Researchers must provide complete and understandable information about the study. The key information must be presented in a concise and focused manner at the beginning of the consent process to help prospective subjects understand why one might or might not want to participate [35]. This includes:

- Purpose and Nature: A clear explanation that the activity is research, its duration, and the procedures involved [35] [36].

- Risks and Benefits: A thorough description of any foreseeable risks, discomforts, and potential benefits, both to the participant and to society [37].

- Voluntary Participation: An explicit statement that participation is voluntary and that refusal to participate involves no penalty or loss of benefits [38].

Participant Comprehension

Simply providing information is insufficient. Researchers must ensure the information is truly understood by the prospective participant [9]. This involves:

- Appropriate Language: Presenting information in language that is understandable to the subject or their representative, typically at or below an 8th-grade reading level [35] [36].

- Avoiding Technical Jargon: Replacing complex scientific terms with common, lay language [36].

- Assessing Understanding: Allocating sufficient time for questions and discussion, and confirming the participant's comprehension of key study elements [35].

Voluntariness

The decision to participate must be made without coercion or undue influence [9]. This requires:

- Freedom from Coercion: Ensuring no explicit or implied threats of penalty are used [34].

- Managing Undue Influence: Carefully considering compensation and other inducements to ensure they do not become an overpowering influence, particularly for vulnerable populations [37].

- Right to Withdraw: Explicitly stating that the participant can discontinue involvement at any time without penalty [38].

Table 1: Core Components of Informed Consent and Their Practical Applications

| Core Component | Key Requirements | Practical Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Information Disclosure [9] | - Concise presentation of key information- Complete details of risks/benefits- Clear description of procedures | - Use a 2-page key information summary [35]- Organize information to facilitate understanding [35] |

| Participant Comprehension [9] | - Understandable language- Assessment of understanding- Opportunity for questions | - Write at an 8th-grade reading level [36]- Use Flesch-Kincaid readability tests [36] |

| Voluntariness [9] | - Free power of choice- Absence of coercion or undue influence- Right to withdraw without penalty | - Scrutinize compensation for undue influence [37]- Explicitly state the right to withdraw [38] |

Regulatory Framework and Documentation

The ethical principles of the Belmont Report are codified in federal regulations, primarily the Common Rule (45 CFR 46) and FDA regulations [39]. While the specific rules may vary, the foundational requirements for informed consent are consistent.

General Requirements for Informed Consent

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) mandates that the consent process must provide sufficient information, time, and opportunity for discussion for the participant to make an informed decision [35]. The process must:

- Begin with a brief, focused presentation of the most important information [35].

- Be sought under conditions that minimize coercion or undue influence [35].

- Be in language understandable to the participant and free of exculpatory language [35].

Required Elements of Informed Consent

The regulations stipulate specific elements that must be present in the consent process. These are categorized into basic and additional elements [35].

Basic Elements include a statement that the study involves research, an explanation of its purpose and duration, a description of procedures, and a disclosure of any foreseeable risks or benefits [37]. Additional Elements may include a statement that participation may involve unforeseen risks, circumstances under which the participant's involvement may be terminated, and the consequences of a participant's decision to withdraw [35].

Table 2: Essential Elements of a Consent Form

| Element Category | Specific Requirements | Regulatory Reference |