Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature: A Methodological Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to conducting systematic reviews of ethical literature (SREL) for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature: A Methodological Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to conducting systematic reviews of ethical literature (SREL) for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It addresses the foundational principles, adapted methodologies, and common challenges unique to synthesizing normative and argument-based literature. Covering the complete process from protocol design to dissemination, the guide explores specialized frameworks like PRISMA-Ethics, strategies for mitigating bias, and techniques for validating review impact. By offering evidence-based best practices and a forward-looking perspective, this resource aims to enhance the rigor, transparency, and utility of ethical syntheses in informing biomedical research and policy.

The What and Why: Defining Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature and Their Role in Research

Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature (SREL) represent a specialized methodological approach within evidence-based research, designed specifically to address normative questions in bioethics and related fields. Unlike standard systematic reviews that primarily synthesize empirical data to assess healthcare interventions, SREL aim to provide comprehensive, systematically structured overviews of ethical issues, arguments, concepts, and reasons found in scholarly literature [1] [2]. These reviews have emerged as distinct scholarly products over the past three decades to address the unique challenges of synthesizing normative literature, with their number steadily increasing and their methodology becoming increasingly standardized [1].

The fundamental purpose of SREL is to identify, analyze, and synthesize normative content relating to morally challenging topics in healthcare, medicine, and biotechnology. This normative literature typically consists of theoretical discussions evaluating practices, processes, or ethical outcomes of courses of action, though it may also include empirical studies used as sources for ethical arguments or descriptions of ethical issues [1] [2]. As the field has evolved, SREL have been referred to by various names including "systematic reviews of argument-based ethics literature," "systematic reviews of reasons," "systematic reviews of normative bioethics literature," and "ethics syntheses," reflecting the methodological diversity within this emerging field [1] [2].

Key Conceptual Differences Between SREL and Standard Systematic Reviews

Nature of Source Material and Research Questions

The most fundamental distinction between SREL and standard systematic reviews lies in the nature of their source materials and research questions. Standard systematic reviews typically address questions of effectiveness, efficacy, or safety of healthcare interventions by synthesizing empirical findings from clinical studies, particularly randomized controlled trials [3]. In contrast, SREL address normative questions about what is ethically justified or desirable, synthesizing theoretical arguments, ethical principles, values, and conceptual analyses found in the bioethics literature [1] [2].

Table: Comparative Analysis of Source Materials and Research Questions

| Aspect | Standard Systematic Reviews | Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature (SREL) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Research Questions | Focus on intervention effectiveness, safety, efficacy (e.g., "Is treatment A better than treatment B for condition X?") | Address normative ethical concerns (e.g., "What are the ethical arguments for and against intervention Y?" "What ethical issues arise in context Z?") |

| Source Materials | Empirical research studies (RCTs, observational studies, qualitative research) | Theoretical normative literature, argument-based publications, conceptual analyses, ethical frameworks |

| Data Extracted | Quantitative outcomes, effect sizes, quality assessments, risk of bias | Ethical issues, moral arguments, ethical principles, values, conceptual distinctions, moral reasoning |

| Typical Applications | Inform clinical guidelines, evidence-based practice, health technology assessments | Identify ethical considerations, map moral arguments, support ethical deliberation, inform policy discussions |

Methodological Adaptations in SREL

SREL require significant methodological adaptations compared to standard systematic reviews, particularly in the analysis and synthesis phases. While standard systematic reviews of quantitative evidence often employ statistical meta-analysis, and qualitative evidence syntheses use thematic analysis, SREL must develop approaches appropriate for synthesizing normative arguments and ethical concepts [1] [4]. The defining characteristic of systematic reviews – the application of explicit, systematic methods to minimize bias – remains crucial in SREL, but the techniques for search, selection, analysis, and synthesis require customization for ethical literature [1].

Analysis of published SREL reveals considerable variation in how these reviews handle methodological challenges. A systematic review of reviews found that while most SREL reported adequately on search and selection methods, reporting was much less explicit for analysis and synthesis methods – 31% did not fulfill any criteria related to the reporting of analysis methods, and only 25% reported the ethical approach used to analyze and synthesize normative information [4]. This methodological gap has prompted the development of specialized reporting guidelines for SREL, known as "PRISMA-Ethics" [1] [2].

Methodological Framework and Protocols for Conducting SREL

Search and Selection Strategies

The search and selection process for SREL shares some commonalities with standard systematic reviews but requires adaptations to identify relevant ethical literature effectively. SREL typically employ comprehensive search strategies across multiple databases, including both biomedical databases (e.g., PubMed, Web of Science) and philosophy/ethics-specific databases (e.g., PhilPapers) [4]. The search syntax must be carefully constructed to capture the conceptual and argument-based nature of ethical literature, often requiring broader search terms and more iterative refinement than searches for empirical literature.

Table: Protocol for SREL Search and Selection Process

| Stage | Standard Systematic Review Protocol | SREL-Specific Adaptations |

|---|---|---|

| Database Selection | Biomedical databases (PubMed, Cochrane Central, Embase) | Combination of biomedical AND ethics/philosophy databases (PubMed, PhilPapers, Google Scholar) |

| Search Strategy | PICO-focused terms, methodological filters | Broader conceptual terms, argument-based terminology, ethical frameworks |

| Selection Criteria | Based on study design, population, intervention, outcomes | Based on relevance to ethical question, type of ethical analysis, normative content |

| Quality Assessment | Risk of bias tools, methodological quality appraisal | Argument quality assessment, conceptual clarity, logical consistency |

| Handling Duplicates | Standard deduplication processes | Additional challenges with overlapping arguments in different publications |

The selection process for SREL involves identifying literature relevant to the ethical question, which may include various types of normative documents such as ethical analyses, conceptual frameworks, position papers, and argument-based discussions. The screening criteria must be developed to capture the breadth of relevant ethical discourse while excluding literature that lacks substantive ethical analysis or merely mentions ethical issues without developing arguments [4].

Data Extraction and Analysis Methods

Data extraction in SREL focuses on capturing normative content rather than empirical outcomes. The development of customized data extraction forms is essential, with fields designed to capture the key elements of ethical discourse relevant to the review question.

Extraction Framework for Normative Content:

- Ethical Issues and Dilemmas: Identification of specific ethical problems, conflicts, or challenging situations

- Ethical Arguments and Reasons: Extraction of premises, conclusions, and logical structure of moral arguments

- Ethical Principles and Values: Documentation of fundamental ethical principles (e.g., autonomy, beneficence, justice) and values invoked

- Ethical Concepts and Theories: Identification of ethical frameworks, theoretical approaches, and conceptual distinctions

- Stakeholders and Perspectives: Analysis of whose interests are considered and how different viewpoints are represented

- Contextual Factors: Documentation of circumstances that influence the ethical analysis [1] [2]

The analytical approach in SREL must be tailored to the nature of normative literature. While some reviews employ qualitative content analysis or thematic synthesis to identify patterns and themes in ethical arguments, others may use more specialized approaches such as ethical analysis frameworks or argument mapping techniques [1]. The synthesis should aim to create a coherent overview of the ethical landscape rather than arriving at a single definitive conclusion, acknowledging the legitimate plurality of ethical perspectives while clarifying points of agreement and disagreement [1] [2].

Applications and Implications of SREL in Research and Policy

Actual Use Patterns of SREL in Scientific Literature

Empirical research on how SREL are actually used reveals important insights about their impact and applications. A recent explorative study analyzing 1,812 citations of 31 published SREL found that these reviews are predominantly cited to support claims about ethical issues, arguments, or concepts, or to mention the existence of literature on a given ethical topic [1] [2]. Interestingly, SREL were cited predominantly within empirical publications across various academic fields, indicating broad, field-independent use of such systematic reviews [2].

Contrary to theoretical expectations, the study found that SREL were rarely used to develop guidelines or to derive specific ethical recommendations, which is often postulated as a primary purpose in methodological discussions [1] [2]. Instead, SREL served as methodological orientations for conducting further ethical reviews or for the practical and ethically sensitive conduct of empirical studies [2]. This gap between expected and actual uses of SREL highlights the need to align methodological development with the real-world applications of these reviews.

Ethical Considerations in Conducting SREL

The conduct of SREL raises unique ethical considerations that distinguish them from standard systematic reviews. While systematic reviewers typically do not collect primary data from human participants and are seldom required to seek institutional ethics approval, SREL nonetheless involve significant ethical dimensions related to voice, representation, and potential impact [5].

Key Ethical Frameworks for SREL:

- Consequentialist Ethics: Focus on maximizing benefit and minimizing harm through cost-benefit analysis of potential impacts on all stakeholders

- Deontological Ethics: Emphasis on inherent rightness or wrongness of actions, adherence to principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, and honesty

- Virtue Ethics: Focus on cultivating virtuous character traits and relationships with various stakeholders

- Ethics of Care: Prioritizes attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness in the review process

- Foucauldian Ethics: Attention to power-knowledge relationships and questioning of taken-for-granted assumptions [5]

Systematic reviewers operating in the ethical domain must practice "informed subjectivity and reflexivity," acknowledging their own perspectives while employing transparent methods to minimize bias [5]. This requires careful consideration of how different stakeholder interests are represented in the review and vigilance about potential conflicts of interest that might influence the review process or findings [5].

Research Reagents and Tools for SREL

Table: Essential Methodological Tools for Conducting SREL

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application in SREL |

|---|---|---|

| Search Databases | PubMed, PhilPapers, Google Scholar, Ethics databases | Comprehensive identification of normative literature across biomedical and philosophical sources |

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA-Ethics (in development), PRISMA | Ensuring transparent and complete reporting of review methods and findings |

| Data Extraction Frameworks | Customized extraction forms for normative content | Systematic capture of ethical issues, arguments, principles, and concepts |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Argument quality appraisal frameworks | Critical evaluation of the strength and validity of ethical arguments |

| Synthesis Methods | Thematic synthesis, ethical analysis, argument mapping | Integration and presentation of normative patterns and ethical positions |

| Citation Tracking | Google Scholar, Scopus | Analysis of usage patterns and impact of published SREL |

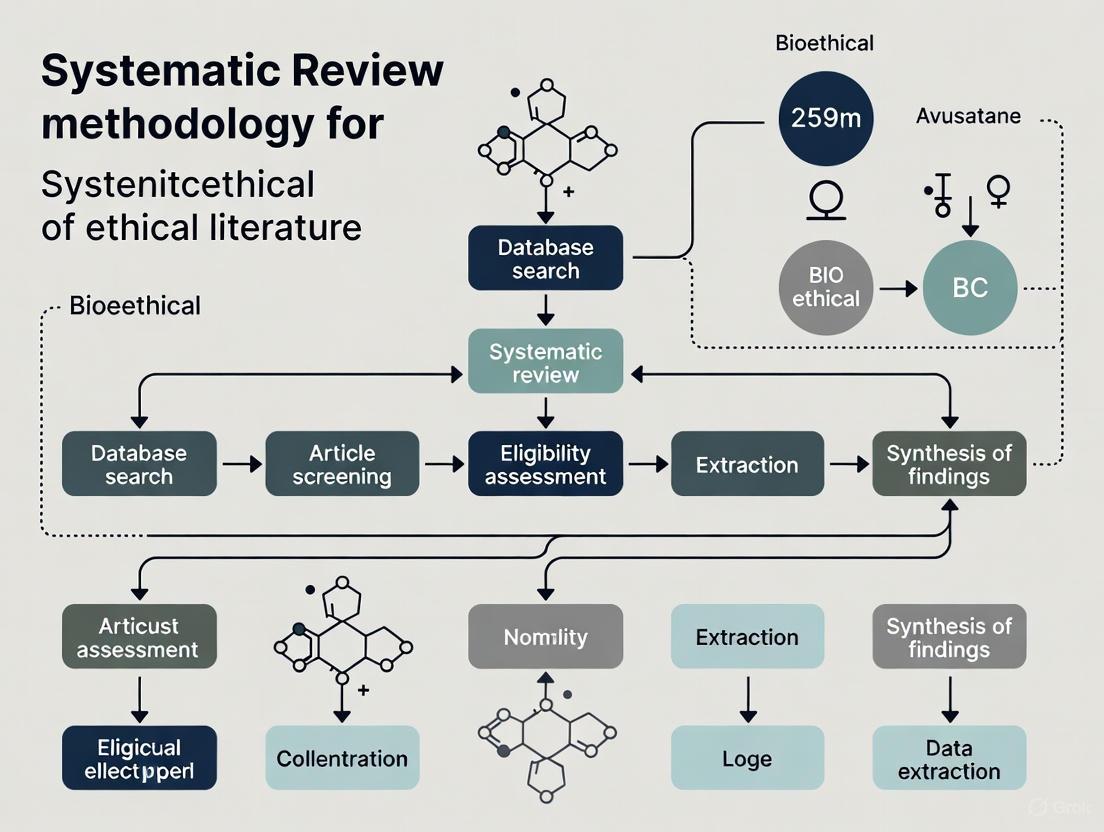

Visualization of SREL Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the complete methodological workflow for conducting Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature, highlighting key stages and decision points:

SREL Methodology Workflow: This diagram illustrates the systematic process for conducting Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature, from question formulation through to application of findings.

Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature represent a distinct and important methodology within the broader landscape of evidence synthesis. While sharing the fundamental systematic approach of standard systematic reviews, SREL differ significantly in their focus on normative questions, their adaptation of methods for handling ethical literature, and their applications in research and policy contexts. The continued methodological refinement of SREL, including the development of specialized reporting guidelines like PRISMA-Ethics, will enhance their rigor, transparency, and utility for addressing complex ethical challenges in healthcare, biotechnology, and beyond. As empirical research on the use of SREL develops, methodology can be further refined to align with the actual needs of researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders who engage with these specialized reviews.

Systematic Reviews for Ethical Literature (SREL) represent a rigorous methodology for synthesizing evidence on ethical considerations in healthcare and policy. As a specialized form of systematic review, SREL applies explicit, accountable methods to identify, select, critically appraise, and synthesize all relevant research on ethical questions [6]. Unlike traditional literature reviews, SREL follows strict, predefined protocols to minimize bias and provide the most comprehensive and transparent overview possible of the ethical landscape surrounding medical interventions, public health policies, and clinical practices [7] [8].

The methodology has evolved from its origins in evidence-based medicine to address increasingly complex questions at the intersection of ethics, policy, and clinical practice. SREL occupies the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence, providing the most reliable foundation for ethical decision-making [9]. By transparently summarizing available evidence, SREL helps ensure that clinical guidelines and health policies reflect not only clinical effectiveness but also ethical considerations, including patient values, risk-benefit assessments, and social implications of healthcare interventions [10] [8].

Methodological Framework for SREL

Core Principles and Protocol Development

The SREL process is built upon foundational principles of transparency, reproducibility, and comprehensiveness [8]. Before commencing a review, researchers must develop a detailed protocol that explicitly defines all methodological approaches. This a priori protocol development is crucial for maintaining methodological rigor and minimizing bias throughout the review process.

The protocol should clearly articulate the ethical research question, often structured using frameworks such as PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) or SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation) for ethical questions. Additionally, the protocol specifies inclusion and exclusion criteria, search strategies, quality assessment tools, data extraction methods, and synthesis approaches appropriate for ethical literature [7] [6].

Table: Key Components of a SREL Protocol

| Protocol Element | Description | Considerations for Ethical Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Research Question | Focused question addressing an ethical issue | May incorporate patient values, stakeholder perspectives, or normative considerations |

| Inclusion Criteria | Explicit criteria for study selection | Often includes diverse study designs (qualitative, quantitative, theoretical) |

| Search Strategy | Comprehensive search approach | Multiple databases with tailored ethical terminology; grey literature inclusion |

| Quality Assessment | Tool for critical appraisal | Must be appropriate for diverse study types (e.g., ROBIS, CASP, JBI) |

| Data Extraction | Systematic data collection | May include ethical frameworks, reasoning patterns, stakeholder positions |

| Synthesis Method | Approach to combining evidence | Narrative, thematic, or qualitative synthesis; meta-ethnography for qualitative studies |

Comprehensive Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive search strategy is fundamental to SREL, aiming to identify all relevant published and unpublished literature to minimize publication bias [7]. The search strategy should be developed in consultation with information specialists and include multiple electronic databases, grey literature sources, and manual searching of reference lists and relevant journals [6].

For ethical literature, search strategies typically combine subject terms (e.g., "amyotrophic lateral sclerosis") with ethical concepts (e.g., "informed consent," "risk-benefit assessment," "patient autonomy") and methodological filters. The search process must be documented thoroughly enough to be reproducible, including specific databases, search dates, and exact search terms used [10].

The study selection process involves a rigorous, multi-stage approach:

- Initial screening of titles and abstracts against predefined inclusion criteria

- Full-text review of potentially relevant articles

- Final selection of studies meeting all eligibility criteria

- Documentation of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion

This process is typically conducted by multiple independent reviewers to minimize selection bias, with disagreements resolved through consensus or third-party adjudication [7] [11].

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Evaluation

Critical appraisal of included studies is essential for assessing the methodological rigor and potential biases in SREL. Various tools are available for assessing risk of bias, with selection dependent on study design [12] [13].

For randomized trials, the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool is recommended, while for non-randomized studies, ROBINS-I is appropriate [12] [13]. Systematic reviews themselves can be assessed using ROBIS, and qualitative studies may be appraised using JBI checklists or CASP qualitative criteria [13]. The risk of bias assessment evaluates potential systematic errors or deviations from the truth in study findings, considering domains such as selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias [13].

Table: Risk of Bias Assessment Tools for Different Study Designs

| Study Design | Assessment Tool | Key Domains Assessed |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic Reviews | ROBIS | Study eligibility criteria; identification and selection of studies; data collection and study appraisal; synthesis and findings |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | Cochrane RoB 2.0 | Randomization process; deviations from intended interventions; missing outcome data; outcome measurement; selection of reported result |

| Non-randomized Studies | ROBINS-I | Confounding; selection of participants; classification of interventions; deviations from intended interventions; missing data; measurement of outcomes; selection of reported results |

| Qualitative Research | JBI Checklist | Philosophical perspective; research design; sampling; data collection; data analysis; interpretation; researcher reflexivity |

| Case-Control/Cohort Studies | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | Selection; comparability; exposure (case-control) or outcome (cohort) |

Data Extraction and Evidence Synthesis

Data extraction in SREL involves systematically collecting relevant information from included studies using standardized forms or templates [7]. For ethical reviews, extraction typically includes both descriptive information (e.g., study characteristics, population, ethical issue) and analytical content (e.g., ethical frameworks, reasoning patterns, stakeholder perspectives, conclusions).

The synthesis approach must be appropriate to the nature of the included studies. For quantitative studies addressing ethical questions, meta-analysis may be appropriate if studies are sufficiently homogeneous [7] [11]. For qualitative evidence, approaches such as thematic synthesis, meta-ethnography, or qualitative content analysis are more appropriate [6]. Many SRELs will use narrative synthesis to summarize findings thematically, particularly when including diverse study designs [6].

The synthesis should explicitly explore relationships in the data, patterns across studies, and sources of heterogeneity. For ethical reviews, this includes considering how contextual factors influence ethical positions and conclusions [6].

Application of SREL in Clinical Guideline Development

Informing Risk-Benefit Assessments

SREL plays a crucial role in informing risk-benefit assessments for clinical interventions, particularly for serious conditions with limited treatment options. For example, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), SREL has revealed that patients are generally willing to accept greater risks than other patient populations when evaluating potential new therapies [10]. This ethical insight directly influences clinical trial design and regulatory decisions, as reflected in FDA guidance that acknowledges the progressive and fatal nature of ALS may affect risk tolerance considerations [10].

The process involves systematically synthesizing evidence on:

- Patient preferences and values regarding potential benefits and acceptable risks

- Clinical outcomes and their relative importance to patients

- Quality of life considerations beyond traditional clinical endpoints

- Burden of treatment and its impact on daily functioning

These syntheses enable guideline developers to balance efficacy evidence with patient-centered considerations, ensuring that recommendations reflect not only what is clinically effective but also what is ethically acceptable and personally meaningful to patients [10].

Supporting Patient-Centered Outcome Selection

SREL methodology helps ensure that clinical trials and guidelines incorporate outcomes that matter to patients, moving beyond traditionally measured endpoints to include patient-experience data and patient-relevant outcomes [10]. For instance, SREL has informed discussions about acceptable endpoints for ALS clinical trials, where the community has expressed that survival alone may not be an ideal endpoint because its use mandates large, long-duration trials [10].

The integration of SREL in outcome selection involves:

- Synthesizing qualitative evidence on patient experiences and priorities

- Identifying outcomes that reflect meaningful functional changes from patient perspectives

- Balancing clinician-reported outcomes with patient-reported outcomes

- Considering novel endpoints that may better capture treatment benefits as perceived by patients

This approach ensures that clinical guidelines recommend treatments based not only on statistical significance but also on clinical meaningfulness from the patient perspective [10].

SREL in Policy Formation and Implementation

Bridging Evidence and Policy Decision-Making

SREL serves as a critical bridge between research evidence and policy decision-making by providing transparent, comprehensive syntheses of complex ethical issues in a format accessible to policymakers [6] [8]. The application of systematic review methods to policy evaluation represents a relatively recent but important development, with the majority of systematic reviews of public policy published after 2014 [6].

The unique contribution of SREL to policy formation includes:

- Identifying policy-relevant ethical considerations across diverse contexts

- Synthesizing evidence on unintended consequences of policy interventions

- Highlighting distributive justice implications and equity considerations

- Clarifying value conflicts underlying policy debates

For example, SREL has been applied to evaluate environmental public policies, where it helps address methodological challenges related to contextual factors and synthesis approaches [6]. This application demonstrates how SREL can incorporate complexity while maintaining methodological rigor.

Addressing Contextual Factors in Policy Implementation

A key challenge in applying SREL to policy is appropriately accounting for contextual factors that influence policy effectiveness and ethical implications [6]. Unlike clinical interventions, policy interventions are highly context-dependent, with social, cultural, and institutional factors significantly modifying outcomes and ethical considerations.

SREL addresses this challenge through:

- Explicit analysis of contextual elements in included studies

- Subgroup analysis exploring how effects vary across settings

- Qualitative comparative analysis identifying configurations of contextual factors associated with particular outcomes

- Realist synthesis approaches examining what works, for whom, and under what circumstances

This contextual sensitivity makes SREL particularly valuable for policy transfer—helping policymakers understand whether and how policies successful in one context might be adapted for different settings [6].

Essential Methodological Tools for SREL Implementation

Research Reagent Solutions for SREL

Implementing rigorous SREL requires specific methodological tools and resources. The table below details essential "research reagents" for conducting high-quality systematic reviews of ethical literature.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for SREL

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Development | PRISMA-P; Cochrane Methodology | Guides structured protocol development; defines scope and methods a priori |

| Search Strategy | Boolean operators; Database thesauri; Grey literature resources | Enables comprehensive search across multiple sources; minimizes publication bias |

| Study Management | Covidence; Rayyan; EndNote | Facilitates duplicate screening; manages references; tracks decisions |

| Risk of Bias Assessment | ROBIS; RoB 2.0; ROBINS-I; JBI checklists | Assesses methodological quality; identifies potential systematic errors |

| Data Extraction | Customized extraction forms; REDCap; Excel templates | Standardizes data collection; ensures consistent information capture |

| Synthesis Tools | RevMan; NVivo; SUMARI | Supports quantitative and qualitative synthesis; facilitates thematic analysis |

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA; ENTREQ; GRASE | Ensures transparent and complete reporting of methods and findings |

specialized SREL Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for conducting Systematic Reviews for Ethical Literature, highlighting key decision points and methodological considerations.

SREL Workflow Diagram: This flowchart illustrates the standard methodology for conducting Systematic Reviews for Ethical Literature, from initial protocol development through to application in guidelines and policy.

Ethical Analysis Framework Integration

The diagram below illustrates how ethical analysis frameworks integrate with standard systematic review methodology to create the specialized SREL approach.

Ethics and Review Integration: This diagram shows how standard systematic review methods combine with ethical analysis frameworks to create the specialized SREL methodology.

Systematic Reviews for Ethical Literature represent a methodologically rigorous approach to synthesizing evidence on ethical considerations in healthcare and policy. By applying explicit, systematic methods to ethical questions, SREL enhances transparency, reduces bias, and provides comprehensive overviews of complex ethical landscapes [7] [8]. The methodology supports both clinical guideline development and policy formation by integrating diverse evidence types, including patient perspectives and contextual considerations [6] [10].

As healthcare continues to grapple with complex ethical challenges, SREL offers a structured approach to ensuring that decisions reflect not only clinical evidence but also ethical principles and patient values. The ongoing methodological development of SREL, including adaptation of synthesis methods for qualitative evidence and approaches to addressing contextual factors in policy applications, will further enhance its utility for informing clinical guidelines and shaping health policy [6].

Application Notes: Core Ethical Theories in Systematic Reviews

Systematic reviews of ethical literature require a clear understanding of the philosophical foundations that underpin moral reasoning. The four major theories—consequentialism, deontology, virtue ethics, and care ethics—provide distinct frameworks for analyzing ethical issues in research contexts, particularly in fields like drug development and healthcare. The following table summarizes their core principles and applications in research.

Table 1: Core Ethical Theories and Their Application to Research

| Ethical Theory | Core Principle | Application in Systematic Reviews | Key Research Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consequentialism | Morality of an action is determined by its outcomes or consequences [14] [15]. | Assessing the potential benefits and harms of a study or intervention; cost-benefit analysis of research impact [5]. | Do the potential benefits of this research outweigh its risks? Which option produces the greatest good for the greatest number? |

| Deontology | Morality is based on adherence to universal duties, rules, and rights, regardless of consequences [14] [15]. | Evaluating adherence to ethical codes (e.g., informed consent, privacy); upholding research integrity and participant rights [5]. | Does this action violate a fundamental moral rule or duty? Are the rights and dignity of all participants being respected? |

| Virtue Ethics | Morality stems from the character and virtues of the moral agent, focusing on "being" rather than "doing" [14] [15]. | Examining the moral character and integrity of researchers and institutions; fostering a culture of research integrity [5]. | What would a virtuous researcher do in this situation? What character traits does this research practice promote or discourage? |

| Care Ethics | Morality centers on empathy, compassion, and maintaining relationships within specific contexts [15]. | Prioritizing the needs and voices of vulnerable participants; ensuring responsive and attentive research relationships [5]. | How does this research impact the well-being of vulnerable groups? Are the caring relationships and specific contexts fully considered? |

Experimental Protocol: Applying a Pluralistic Ethical Framework

Objective: To conduct a systematic review of an ethical dilemma in drug development (e.g., ventilator allocation during a pandemic, inclusion of vulnerable populations in clinical trials) using a pluralistic framework that integrates all four ethical theories.

Methodology:

- Case Identification: Define the specific ethical dilemma and gather relevant research literature, policy documents, and case studies.

- Multi-Perspective Analysis: Analyze the dilemma through each distinct ethical lens:

- Consequentialist Analysis: Identify all stakeholder groups. Map and weigh the potential positive and negative outcomes (e.g., health outcomes, economic costs, social trust) for each group resulting from different policy options [15].

- Deontological Analysis: Identify relevant moral rules, duties, and rights (e.g., duty to care, right to life, principle of justice). Evaluate which options uphold or violate these duties, irrespective of outcomes [15] [5].

- Virtue Ethics Analysis: Reflect on the character traits a "good" healthcare institution or researcher should exemplify (e.g., compassion, justice, wisdom). Determine which course of action aligns with these virtues [14] [15].

- Care Ethics Analysis: Focus on the specific relationships and contexts involved. Assess how different options affect the most vulnerable parties and whether they are based on attentive, responsive care [15].

- Synthesis and Resolution: Compare the results from each analytical lens.

- Note where the different theories converge on a recommended action.

- Where they conflict, document the ethical tensions. Use these insights to develop a nuanced, context-sensitive recommendation that acknowledges the complexity of the dilemma [15].

Visualization of Ethical Decision-Making

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for applying a pluralistic ethical framework to a problem in systematic reviews, integrating the four core theories.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents for Ethical Analysis

Table 2: Essential Conceptual Tools for Ethical Analysis in Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Ethical Analysis |

|---|---|

| Ethical Framework | Serves as a structured heuristic or model to guide decision-making in complex moral situations [16]. |

| Systematic Review Protocol | Defines the plan for the review a priori; ensures transparency, minimizes bias, and upholds methodological rigor (deontology) [5]. |

| Stakeholder Map | Identifies all parties affected by a decision or research outcome; crucial for consequentialist and care ethics analyses. |

| PRISMA Guidelines | Provides a standardized framework for reporting systematic reviews; ensures transparency and reproducibility (deontology) [17]. |

| Informed Consent Template | A procedural tool designed to operationalize the deontological principle of respect for persons and autonomy [18] [17]. |

| Code of Conduct / Ethics | Establishes explicit rules and professional duties for researchers, underpinned by deontological ethics [18] [16]. |

| Reflexivity Journal | A practice from qualitative and participatory research that fosters virtue ethics by encouraging researcher self-awareness and critical examination of their own biases and positionality [5]. |

| (+)-Thienamycin | (+)-Thienamycin, CAS:59995-64-1, MF:C11H16N2O4S, MW:272.32 g/mol |

| Imipramine Hydrochloride | Imipramine Hydrochloride, CAS:113-52-0, MF:C19H25ClN2, MW:316.9 g/mol |

Application Notes: Core Ethical Constructs in Systematic Reviews

Systematic reviews are a powerful methodology for synthesizing research to inform policy and practice, yet they introduce distinct ethical considerations that extend beyond conventional research ethics. Unlike primary researchers, systematic reviewers typically use publicly accessible documents and are seldom required to seek institutional ethics approval [5]. However, given their influence, ethical conduct is paramount to ensure the integrity and social responsibility of the synthesized evidence [18].

The ethical deliberation in systematic reviews can be navigated through several key constructs, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Ethical Constructs and Principles in Systematic Review Methodology

| Ethical Construct | Definition & Core Arguments | Application in Systematic Review |

|---|---|---|

| Consequentialism/Utilitarianism | An ethical theory that judges actions based on their outcomes; the goal is to maximize overall benefit and minimize harm [5]. | Reviewers conduct a cost-benefit analysis to justify the review's purpose and resource use, aiming for the greatest positive impact on policy, practice, and further research [5]. |

| Deontology/Universalism | A rights-based theory asserting that certain actions are inherently right or wrong, regardless of their consequences. It is guided by principles like beneficence (do good), non-maleficence (prevent harm), and justice [5]. | Reviewers adhere to strict, a priori protocols, define constructs operationally, and use exhaustive search strategies to minimize bias and ensure procedural justice [5]. |

| Virtue Ethics | Focuses on the character and virtues of the moral agent rather than on rules or consequences; emphasizes integrity, care, and reflexivity [5]. | Reviewers practice "informed subjectivity and reflexivity," continuously examining their own biases, values, and relationships with various stakeholders throughout the review process [5]. |

| Ethics of Care | Prioritizes attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness within relational contexts [5]. | Applied in participatory reviews where practitioners are co-reviewers, ensuring the review addresses their lived experiences and generates actionable knowledge for their local context [5]. |

| Foucauldian Ethics | Highlights the relationship between power and knowledge, focusing on questioning dominant discourses and metanarratives [5]. | Reviewers problematize taken-for-granted assumptions in a field, giving voice to marginalized perspectives and challenging power imbalances in the existing literature [5]. |

| Research Misconduct | Includes fabrication, falsification, plagiarism, and other practices that seriously deviate from accepted ethical standards [18]. | Addressed by promoting transparency, data sharing, establishing robust detection mechanisms, and educating researchers to uphold integrity [18]. |

| Conflict of Interest | A situation where a reviewer's personal, professional, or financial interests could unduly influence their judgment or the review's findings [18] [5]. | Reviewers must disclose all funding sources and manage potential conflicts, for example, by seeking diverse funding to avoid undue influence from a single vested interest [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Ethical Review Conduct

Protocol for an Interpretive Thematic Synthesis

Thematic synthesis is a common method for integrating qualitative findings, which involves a rigorous process to ensure ethical representation of the original study participants' voices [19].

Title: Ethical Thematic Synthesis for Qualitative Evidence

Objective: To construct holistic understandings of educational, social, or health-related phenomena by ethically synthesizing subjective experiences from diverse populations, with particular attention to less-represented viewpoints.

Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Identifying an Appropriate Epistemological Orientation: The review must be positioned within an interpretive epistemology, which is aligned with teleological ethics and focuses on constructing understanding from subjective experiences [5].

- Line-by-Line Coding: Textual findings from the included primary studies are coded line-by-line [19]. Ethically, this stage requires a "questioning gaze" and genuine engagement to ensure the original meanings and contexts are preserved.

- Develop Descriptive Themes: The codes are organized into descriptive themes that summarize the content of the primary studies [19].

- Generate Analytical Themes: The descriptive themes are developed further into analytical themes that go beyond the primary studies to address the specific review question, constructing a new, ethically sound interpretation [19].

Protocol for a Quantitative Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis provides a statistical synthesis of quantitative data, and its ethical conduct hinges on transparency and the mitigation of bias at every stage.

Title: Ethical Meta-Analysis Workflow for Quantitative Data

Objective: To statistically combine data from multiple studies to calculate an overall effect, while ethically addressing issues of publication bias, data quality, and transparent reporting.

Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Formulate Review Question: The research question is structured using a framework like PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) to ensure clarity and focus [20].

- Define A Priori Inclusion Criteria: Before commencing the review, pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies are established and documented in a protocol. This is a key deontological practice to prevent biased post hoc decisions [5].

- Systematic Search and Study Selection: An exhaustive search is conducted across multiple databases to identify all relevant published and unpublished work, mitigating publication bias [21].

- Extract and Group Data: Quantitative data related to outcomes are extracted from included studies and grouped for analysis. Data is often presented in tables for clarity [19].

- Statistical Analysis and Forest Plot Generation: Data from individual studies are combined using statistical methods to calculate an overall effect [19]. The results are typically displayed using a forest plot, which graphically shows the point estimate and confidence interval for each study and the pooled result [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Conducting Ethical Systematic Reviews

| Item | Function & Ethical Rationale |

|---|---|

| A Priori Protocol | A detailed, pre-published plan for the review methods. It decreases biased post hoc changes and increases transparency, a core tenet of deontological ethics and research integrity [20] [21]. |

| Bibliographic Databases (e.g., Scopus, MEDLINE) | Repositories of peer-reviewed literature. An exhaustive search across multiple databases is a methodological and ethical imperative to minimize selection bias and give a fair representation of existing evidence [18] [20]. |

| Grey Literature Sources | Includes theses, reports, and unpublished studies. Searching these sources helps counter publication bias, ensuring that studies with null or negative findings are included, which is crucial for an unbiased, consequentialist assessment of an intervention's true effect [20]. |

| Data Extraction Tools | Software or structured forms used to consistently capture data from included studies. This ensures accuracy and reliability, upholding the ethical principle of beneficence by producing trustworthy findings [19]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, RevMan) | Applications for performing meta-analyses. Using robust, reproducible scripts (e.g., in R) aligns with the ethical push for open science and transparency, allowing others to verify and build upon the work [18] [22]. |

| Quality Appraisal Tool (e.g., JBI Checklists) | Standardized checklists to evaluate the methodological quality of primary studies. This is an ethical duty of care to the review's audience, signaling the confidence they can place in the synthesized findings [20]. |

| Conflict of Interest Disclosure Form | A formal document for declaring competing interests. Its use is a fundamental practice of virtue ethics, demonstrating honesty and integrity to maintain public trust in the review's conclusions [5]. |

| Dihydrocapsaicin | Dihydrocapsaicin, CAS:19408-84-5, MF:C18H29NO3, MW:307.4 g/mol |

| Isoforskolin | Isoforskolin, CAS:64657-21-2, MF:C22H34O7, MW:410.5 g/mol |

Systematic reviews represent the highest level of evidence synthesis in research, and their application to ethical literature is increasingly crucial in navigating complex moral landscapes in fields like healthcare, technology, and drug development. Unlike traditional narrative reviews, systematic reviews of ethical literature employ rigorous, pre-defined methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesize all relevant research addressing a specific ethical question [23]. This methodology minimizes bias and provides a robust foundation for evidence-based ethical decision-making [23] [24].

The distinctive nature of ethical inquiry—often dealing with normative claims, principles, and qualitative arguments—necessitates a tailored approach to systematic review methodology. This application note establishes clear criteria for when to conduct such reviews and provides detailed protocols for their execution, framed within the broader context of advancing systematic review methodology for ethical literature research.

Decision Framework: When to Conduct a Systematic Review of Ethical Literature

A systematic review of ethical literature is resource-intensive and should not be undertaken for every ethical question. The following criteria provide a structured framework for determining when such a rigorous approach is justified. These conditions are often interdependent, and the presence of multiple criteria strengthens the case for conducting a systematic review.

Table 1: Decision Criteria for Conducting a Systematic Review of Ethical Literature

| Criterion | Description | Indicators for Need |

|---|---|---|

| Contentious or Unresolved Debate | The ethical issue is subject to significant disagreement in academic, professional, or public discourse. | Polarized literature; conflicting guidelines; ongoing public or policy disputes. |

| Emerging Technology or Field | Novel developments create new ethical terrains where norms are not yet established. | New capabilities (e.g., AI, gene editing); preliminary ethical discussions; anticipated societal impact. |

| Guideline or Policy Development | A concrete need exists to inform authoritative documents, institutional policies, or regulatory frameworks. | Commissioned reviews; legislative processes; development of professional standards. |

| Identifying Conceptual Gaps | The goal is to map the conceptual structure of the literature to identify under-explored areas. | Fragmented research; lack of conceptual clarity; need for theoretical synthesis. |

| Substantial and Growing Literature | A critical mass of publications exists, making a narrative synthesis impractical or prone to bias. | Hundreds of potentially relevant papers; literature spanning multiple disciplines. |

The following decision pathway synthesizes these criteria into a practical workflow for researchers:

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Systematic Review of Ethical Literature

This section provides a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for conducting a systematic review of ethical literature, from initial planning to final dissemination.

Protocol Development and Registration

Before commencing the review, a detailed protocol must be developed. This serves as a blueprint, ensuring transparency and reducing bias [23] [25].

Define a Clear Research Question: Formulate a focused, answerable question. While the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework is standard for clinical questions, ethical reviews may adapt this to focus on stakeholders, ethical interventions or principles, comparators, and ethical outcomes [23] [24]. Example: "In the context of AI-driven drug development (Stakeholders), how is the principle of accountability (Intervention) operationalized compared to human-involved research (Comparator) in terms of assigned responsibility in case of error (Outcome)?"

Develop and Register the Protocol: The protocol should detail all subsequent steps. Registering the protocol in a public registry like PROSPERO enhances transparency, reduces the risk of reporting bias, and allows for peer feedback on the methodology [23] [25].

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive, unbiased search is fundamental to the systematic review process.

Information Sources: Identify relevant bibliographic databases. These typically include:

- Philosophy/Ethics Databases: PhilPapers, EthicsWeb

- Multidisciplinary Databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar

- Biomedical/Life Science Databases: PubMed, EMBASE (for bioethics topics) [26] [27]

- Grey Literature: Institutional repositories, conference proceedings, and policy documents should be considered based on the review's scope [23].

Search String Formulation: Develop sensitive and specific search strings using keywords, synonyms, and Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) [23] [26]. For ethical topics, this must encompass both conceptual language (e.g., "autonomy", "justice") and context-specific terminology (e.g., "dementia", "AI"). An iterative approach is recommended, refining the search based on initial results.

Study Selection Process: Implement a two-stage screening process using pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria [23] [26].

- Title/Abstract Screening: Screen all retrieved records against eligibility criteria.

- Full-Text Screening: Obtain and assess the full text of potentially relevant records.

The study selection process is a critical, multi-stage workflow that ensures the final included studies are relevant and of high quality:

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data Extraction: Develop and pilot a standardized data extraction form to ensure consistency [23] [26]. Data fields may include:

- Bibliographic information

- Study context (e.g., population, technology)

- Ethical principles or frameworks discussed (e.g., autonomy, beneficence, justice) [27]

- Methodological approach (e.g., conceptual analysis, empirical ethics)

- Key findings and conclusions

- Implications stated by authors

Quality Assessment (Critical Appraisal): Assessing the quality of ethical literature is complex due to its often non-empirical nature. Use appropriate tools and criteria for different study types. One approach is to assess the clarity of the research question, the rigor of the argumentation, the consideration of counter-arguments, and the coherence of the conclusions [26].

Data Synthesis and Visualization

Synthesis in ethical reviews is typically qualitative, as meta-analysis is usually not appropriate for normative content.

Qualitative Thematic Synthesis: This method is specifically designed for synthesizing qualitative reports and involves three stages [27]:

- Line-by-line coding of the text of the findings/results sections of included studies.

- Grouping codes into related content areas to construct descriptive themes.

- Developing analytical themes that go beyond the original content to generate new interpretive constructs.

Data Visualization: Effective visualizations are essential for communicating the results of complex syntheses. The field has seen a "graphics explosion," with over 200 different graph types now available [29] [30]. Key visualizations for ethical systematic reviews include:

- PRISMA Flow Diagram: To illustrate the study selection process [28].

- Evidence Atlases: To display the geographical or contextual distribution of studies [28].

- Heat Maps: To show the volume of evidence across different ethical principles and contexts, helping to identify knowledge clusters and gaps [28].

- Conceptual Models/Logic Models: To visualize the complex systems and relationships between technologies, actions, and ethical outcomes [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ethical Systematic Reviews

Unlike wet-lab research, the "reagents" for a systematic review are primarily conceptual and methodological tools. The following table details the essential components required for a rigorous review of ethical literature.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Registries | PROSPERO, Open Science Framework | Pre-register review protocol to enhance transparency, reduce bias, and allow for peer feedback. |

| Search Databases | PhilPapers, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar | Identify relevant scholarly literature across disciplines (philosophy, biomedicine, technology). |

| Reference Management | EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley | Manage bibliographic data, deduplicate records, and facilitate citation. |

| Screening Software | Rayyan, Covidence | Streamline the title/abstract and full-text screening process with blind collaboration between reviewers. |

| Data Extraction Tools | Custom Excel/Google Sheets forms, REDCap | Systematically extract and manage data from included studies using standardized, pilot-tested forms. |

| Quality Appraisal Tools | Custom critical appraisal checklists for normative literature | Assess the rigor, clarity, and coherence of ethical analyses and arguments within included studies. |

| Synthesis Software | NVivo, Citavi, Tableau | Support qualitative thematic synthesis and create dynamic visualizations of findings [31]. |

| Ailanthone | Ailanthone, CAS:981-15-7, MF:C20H24O7, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gomisin M2 | Gomisin M2|CAS 82425-45-4|For Research Use | Gomisin M2 is a natural lignan with research applications in cancer, immunology, and virology. This product is for research use only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

Conducting a systematic review of ethical literature is a methodologically demanding but invaluable process for clarifying contentious debates, informing policy in emerging fields, and mapping the conceptual landscape of ethical scholarship. By applying the decision framework and detailed protocols outlined in this application note, researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals can ensure their reviews are conducted with the rigor, transparency, and comprehensiveness that the complexity of ethical questions demands. This structured approach ultimately generates more reliable, trustworthy, and actionable syntheses to guide ethical decision-making.

The Practitioner's Guide: Executing a Rigorous SREL from Protocol to Synthesis

Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature (SREL) represent a rigorous methodological approach designed to provide a comprehensive overview of ethical issues, arguments, or concepts on a specific ethical topic. Unlike traditional systematic reviews that primarily synthesize empirical data, SREL analyzes and synthesizes normative literature, discussing ethical issues, evaluating practices, and formulating ethical judgments. The fundamental purpose of a SREL is to bring transparency, objectivity, and systematic structure to the exploration of ethical questions, thereby minimizing bias and ensuring reproducible results. As the number of SREL has steadily increased over recent decades, the methodology has become increasingly subjected to critical considerations, particularly regarding its appropriate application and impact [1].

The distinction between SREL and conventional systematic reviews is profound. While medical systematic reviews often focus on quantitative data meta-analysis, SREL must navigate theoretical normative content that requires alternative reviewing approaches. This unique characteristic of ethical literature necessitates specific methodological adjustments to ensure the reviews remain comprehensive and systematically structured. The development of a robust protocol is therefore not merely a procedural formality but a foundational element that determines the scientific rigor, credibility, and ultimate utility of the review [1]. Proper protocol development ensures that SREL can fulfill their potential as valuable inputs for clinical decision-making, guideline development, or health technology assessments, despite current evidence suggesting they are rarely used specifically to develop guidelines or derive ethical recommendations as often postulated in theoretical literature [1].

Foundational Elements of a SREL Protocol

The SREL Research Question

Formulating a precise and answerable research question is the critical first step in developing a SREL protocol. The question must be specific enough to provide clear boundaries for the review while encompassing the core ethical dimensions to be explored. A well-constructed research question in ethical reviews typically captures the central ethical problem, the stakeholders affected, the context in which the ethical issue arises, and the normative concepts relevant to its analysis.

The PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome), widely used in clinical systematic reviews, often requires adaptation for SREL. A more suitable framework for ethical reviews may focus on ethical agents, actions or interventions, contextual factors, and ethical values or principles. For instance, a research question might be framed as: "In the context of critical care decision-making (context), what ethical arguments (ethical principles) do healthcare professionals (ethical agents) invoke regarding the limitation of life-sustaining treatment (actions) for incapacitated adult patients (population)?" This structured approach ensures the research question captures the normative nature of the inquiry while maintaining the systematic rigor required for a comprehensive review [32].

Defining the Scope and Objectives

Clearly defining the scope and objectives of a SREL establishes its conceptual boundaries and guides all subsequent methodological decisions. The scope should explicitly state what the review will include while implicitly indicating what it will exclude. Key considerations when defining scope include:

- Ethical Focus: Specify the precise ethical aspect under investigation (e.g., ethical issues, arguments, concepts, or principles).

- Domain Limitations: Delineate the practical or clinical domain in which the ethical considerations arise (e.g., specific medical specialties, research contexts, or healthcare settings).

- Literature Boundaries: Identify the types of literature that will be considered relevant (e.g., philosophical analyses, empirical ethics studies, policy documents, or case discussions).

The objectives flowing from this scope should be articulated as clear, actionable goals that the review intends to accomplish. These may include mapping the landscape of ethical concerns in an emerging field, analyzing the quality and structure of arguments on a contested issue, identifying consensus and disagreement points in ethical debates, or tracing the evolution of specific ethical concepts over time. A well-defined scope prevents mission creep during the review process and ensures the final product remains focused and manageable [25].

Table 1: Key Differences Between SREL and Conventional Systematic Reviews

| Characteristic | Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature (SREL) | Conventional Systematic Reviews |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Material | Normative literature (ethical arguments, concepts, issues) [1] | Empirical studies (clinical trials, observational studies) |

| Analytical Focus | Ethical issues, reasons, arguments, and conceptual analyses [1] | Quantitative data, effect sizes, statistical significance |

| Synthesis Method | Structured analysis and synthesis of normative content [1] | Meta-analysis of quantitative data |

| Primary Output | Overview of ethical landscape, argumentative patterns, conceptual clarity | Pooled effect estimates, risk-benefit assessments |

| Common Applications | Identifying ethical considerations, informing policy debates, clarifying concepts [1] | Informing clinical guidelines, establishing treatment efficacy |

Developing Eligibility Criteria for SREL

Principles and Purpose of Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria serve as the foundational framework that determines which studies or articles will be included in a systematic review. In the context of SREL, these criteria ensure the review's relevance, reliability, and validity while minimizing bias and increasing transparency. Eligibility criteria function similarly in systematic reviews as in primary research—they reflect the analytic framework and key questions derived from the research question. These criteria are powerful tools for either widening or narrowing the scope of a review and provide essential information for determining whether different reviews can be compared or combined [32].

The overarching goal when developing eligibility criteria is to strike a balance between obtaining adequate information to answer the research question without obscuring the results with irrelevant literature. Inappropriate eligibility criteria may limit the applicability of the review or result in the inclusion of studies that either overestimate or underestimate certain perspectives. For example, using studies of twin pregnancies in a review of preterm labor management for low-risk women would represent a significant misapplication of criteria. Review teams must work collaboratively to find this balance, always prioritizing the minimization of bias related to which studies are selected [32].

Structured Approach to Eligibility Criteria: The PICOTS Framework

A systematic approach to developing eligibility criteria for SREL involves adapting the PICOTS framework (Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes, Timing, Setting) to the specific context of ethical literature [32]:

- Population: Define the relevant moral agents, stakeholders, or patient populations affected by the ethical issue. This may include conditions, disease severity and stage, comorbidities, and patient demographics.

- Intervention/Exposure: Specify the ethical interventions, technologies, or situational exposures that raise ethical considerations. This could include dosage, frequency, method of administration for medical interventions, or specific ethical dilemmas.

- Comparators: Identify relevant comparison points, which may include alternative ethical frameworks, different ethical positions, placebo, usual care, or active control.

- Outcomes: Determine the ethical outcomes of interest, such as ethical issues identified, arguments advanced, concepts applied, or resolutions proposed.

- Timing: Consider the duration of follow-up in empirical studies or the historical period for theoretical works.

- Setting: Define the contexts where ethical issues arise, such as primary care, specialty care, inpatient settings, or research institutions, including consideration of co-interventions.

Table 2: SREL Eligibility Criteria Framework with Examples

| PICOTS Element | Considerations for SREL | Example Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Moral agents, stakeholders, patient groups | "Adults with decision-making capacity in critical care settings" |

| Intervention/ Phenomenon | Technologies, treatments, situations raising ethical issues | "Genetic testing for late-onset neurological conditions" |

| Comparators | Alternative ethical positions or frameworks | "Deontological vs. consequentialist approaches to truth-telling" |

| Outcomes | Ethical issues, arguments, concepts | "Identification of autonomy-related concerns in shared decision-making" |

| Timing | Publication date ranges, historical periods | "Literature published from 2000 to present reflecting contemporary bioethics" |

| Setting | Context where ethical issues emerge | "Tertiary care hospitals in high-income countries" |

| Study Types | Normative and empirical ethics literature | "Peer-reviewed articles presenting ethical analysis; empirical studies of ethical attitudes" |

Additional Eligibility Considerations for SREL

Beyond the core PICOTS framework, several additional considerations require careful deliberation when establishing SREL eligibility criteria:

- Types of Studies: Determine which study designs will be included. While SREL traditionally focus on normative and theoretical literature, there may be justification for including empirical studies that illuminate ethical perspectives or practices. The team must decide whether to limit to specific publication types or include a broader range of scholarly work [32].

- Language Restrictions: Consider whether to include studies in languages other than English. While positive findings may be more likely to be published in high-profile English-language journals, limiting to English-only publications might introduce bias. Empirically, the bias associated with limiting to English-language reports has been shown to be small, but this must be balanced against comprehensive coverage [32].

- Gray Literature: Decide whether to include "gray" or "fugitive" literature such as government reports, conference proceedings, book chapters, and published dissertations. Since journals may publish positive or statistically significant results in empirical ethics, finding gray literature of unpublished nonsignificant or null results may indicate publication bias [32].

- Publication Date: Establish date parameters for the literature search, particularly when there has been a change in policy, practice, or technology that makes older ethical discussions less applicable to contemporary contexts [32].

Methodology and Workflow Design

Developing a comprehensive search strategy is paramount to ensuring the SREL captures all relevant literature. The strategy should be designed to maximize sensitivity while maintaining specificity, balancing the risk of missing relevant studies against including excessive irrelevant material. Key elements include:

- Database Selection: Identify relevant multidisciplinary and specialized databases (e.g., Philosopher's Index, PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science) that cover bioethical and related literature.

- Search Terms: Develop a structured vocabulary of controlled terms and keywords related to the ethical concepts, contexts, and populations under review. These should be iteratively refined through preliminary scoping searches.

- Search Syntax: Document the exact search syntax for each database, including Boolean operators, proximity searching, and field restrictions.

- Supplementary Approaches: Implement citation tracking, reference list scanning, and contact with experts in the field to identify additional relevant literature.

The search strategy should be documented with sufficient detail to allow replication, and consideration should be given to the use of emerging AI-assisted search tools that can enhance the efficiency and accuracy of literature identification [25].

Study Selection and Data Extraction Process

A transparent, reproducible process for study selection and data extraction forms the core of SREL methodology. The selection process should involve:

- Piloting: Initial calibration exercises to refine eligibility criteria and ensure consistent application across review team members.

- Dual Review: Independent screening of titles/abstracts and full-text publications by at least two reviewers, with procedures for resolving disagreements through consensus or third-party adjudication.

- Documentation: Maintenance of detailed records of the selection process, typically using a PRISMA flow diagram to document the number of studies identified, included, and excluded at each stage.

For data extraction, the protocol should specify:

- Structured Forms: Development of standardized data extraction forms, either paper-based or electronic, that capture all relevant information from included studies.

- Pilot Testing: Preliminary testing and refinement of data extraction forms to ensure they capture all necessary information.

- Dual Extraction: Independent data extraction by multiple reviewers for at least a subset of studies to ensure consistency and accuracy.

The protocol should explicitly address how normative content will be extracted and categorized, including definitions of ethical concepts, classification of argument types, and documentation of ethical reasoning structures [1] [25].

Diagram 1: SREL Development Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential stages in developing a Systematic Review of Ethical Literature, from initial protocol definition through final reporting.

Data Synthesis and Analysis Approach

The synthesis and analysis phase represents the most methodologically challenging aspect of SREL. Unlike quantitative meta-analysis, synthesis of ethical literature requires a structured approach to analyzing and integrating normative content. The protocol should specify:

- Analytical Framework: The theoretical approach that will guide analysis, which may be based on principle-based ethics, casuistry, narrative ethics, or other methodological frameworks.

- Categorization Scheme: How ethical concepts, issues, and arguments will be identified, categorized, and compared across studies.

- Relationship Mapping: Procedures for identifying relationships between different ethical positions, tracing the development of arguments, and identifying consensus and disagreement points.

- Quality Assessment: Approaches for assessing the quality of ethical arguments, which may differ substantially from quality assessment tools for empirical research.

The synthesis should aim to produce more than merely a summary of included studies; it should generate novel insights through the systematic organization and analysis of the ethical literature [1].

Implementation and Reporting

The Research Toolkit for SREL

Conducting a high-quality SREL requires both methodological expertise and appropriate tools to manage the complex review process. The following table outlines essential components of the SREL research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Conducting SREL

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in SREL Process |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Registration | PROSPERO, Open Science Framework | Pre-register review protocol to enhance transparency and reduce bias [25] |

| Reference Management | EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley | Manage citations, remove duplicates, organize full-text articles |

| Screening Tools | Covidence, Rayyan, DistillerSR | Facilitate blinded screening process, manage conflicts, track decisions [33] |

| Data Extraction | Custom electronic forms, REDCap | Standardize data collection from included studies, maintain consistency [25] |

| Quality Assessment | Custom quality appraisal tools tailored to normative literature | Assess robustness of ethical arguments and conceptual analyses |

| Synthesis Support | NVivo, Qualitative analysis software | Facilitate coding and categorization of ethical concepts and arguments |

| Reporting Guidelines | PRISMA, PRISMA-Ethics [1] | Ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting of review methods and findings |

| Taraxerone | Taraxerone|SIRT1 Activator for Research | Taraxerone is a potent SIRT1 activator for research into acute lung injury and inflammation. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

| Ergosterol Peroxide | Ergosterol Peroxide|High-Purity Research Compound |

Protocol Registration and Reporting Standards

Registering the SREL protocol before commencing the review proper represents a critical step in ensuring methodological rigor and transparency. Protocol registration:

- Minimizes Bias: Prevents post hoc changes to methods based on emerging findings.

- Enhances Transparency: Makes the review methods publicly accessible for scrutiny.

- Promotes Collaboration: Helps avoid duplication of effort and identifies potential collaborators.

- Facilitates Peer Review: Allows for methodological feedback before substantial work has been completed.

Several registries accept systematic review protocols, with PROSPERO being the most prominent for health-related reviews. When reporting the completed review, authors should adhere to relevant reporting guidelines such as the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement, with consideration of emerging extensions specifically designed for ethical reviews, such as PRISMA-Ethics [1] [25].

Diagram 2: SREL Protocol Components. This diagram shows the essential and supporting elements that constitute a comprehensive protocol for Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature.

Developing a robust protocol for Systematic Reviews of Ethical Literature requires careful attention to the unique characteristics of normative literature while maintaining the systematic rigor expected of all scholarly reviews. By formulating precise research questions, developing comprehensive eligibility criteria through frameworks like PICOTS, designing transparent methodologies, and implementing appropriate synthesis approaches, researchers can produce SREL that provide meaningful contributions to ethical discourse. The exponential growth in SREL publications in recent years reflects increasing recognition of their value in mapping ethical landscapes, clarifying conceptual issues, and informing policy debates [1].

As the methodology continues to evolve, emerging trends such as living systematic reviews, AI-assisted literature screening, and the integration of real-world evidence offer promising avenues for enhancing the efficiency, relevance, and impact of SREL [25]. By adhering to rigorous protocol development standards and maintaining flexibility to incorporate methodological innovations, researchers can ensure that SREL continue to fulfill their vital role in providing systematic, transparent, and comprehensive overviews of ethical literature across diverse domains of inquiry.

Systematic reviews of ethical literature represent a critical methodological tool for synthesizing normative and empirical research in bioethics, sociology, and related fields. Unlike systematic reviews of clinical interventions, ethical literature reviews face unique challenges including diverse publication venues, non-standardized terminology, and a significant volume of grey literature [34] [35]. The methodological rigor required for comprehensive searching in this domain is essential for minimizing bias and ensuring the validity and reliability of review findings [5]. This article establishes detailed application notes and protocols for conducting systematic searches of ethical literature, addressing both traditional academic databases and non-traditional grey literature sources while navigating the distinctive lexical challenges inherent to this field.

Database Search Strategies for Ethical Literature

Core Database Selection

Identifying relevant literature on ethical topics requires searching beyond standard biomedical databases to encompass philosophical and interdisciplinary sources. The following table summarizes essential databases for ethical literature reviews:

Table 1: Core Databases for Ethical Literature Searches

| Database | Primary Focus | Search Considerations | Subject Headings Available |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | Biomedical literature | Includes bioethics journals; uses MeSH terms | Yes (MeSH) |

| Philosopher's Index | Philosophical literature | Covers ethics-specific publications | Limited |

| Web of Science | Multidisciplinary | Good for identifying citing references | No |

| EMBASE | Biomedical and pharmacological | Strong European coverage | Yes (EMTREE) |

| CINAHL | Nursing and allied health | Contains clinical ethics content | Yes (CINAHL Headings) |

| Scopus | Multidisciplinary | Broad coverage of social sciences | No |

As demonstrated in a systematic review of normative ethics literature, searches should typically incorporate multiple databases to ensure adequate coverage, with 93% of published reviews reporting the databases used [35]. Specialized philosophical databases like Philosopher's Index are particularly valuable for capturing explicitly normative content that may not be indexed in biomedical databases [36].

Search Syntax and Term Development

Developing effective search strategies for ethical literature requires addressing the disciplinary diversity of publication venues and terminology. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach:

- Preliminary Scoping: Conduct limited searches of key articles to identify relevant terminology and indexing practices [35].

- Term Harvesting: Extract keywords from relevant articles, including synonyms, related terms, and disciplinary-specific phrasing.

- Boolean Structure: Construct search strings using Boolean operators that account for conceptual complexity:

- Adaptation for Databases: Modify syntax according to database-specific requirements, including appropriate field codes and truncation characters [37].

A review of normative literature found that only 39% of reviews provided replicable search strings, highlighting the need for greater transparency in reporting search methodologies [35].

Grey Literature Search Protocol

Grey literature represents a substantial component of ethical literature reviews, particularly for identifying policy documents, institutional guidelines, and emerging ethical discourses not yet captured in academic publications. Grey literature is defined as materials "produced on all levels of government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats, but which is not controlled by commercial publishers" [38]. Incorporating grey literature minimizes publication bias and provides access to the most current guidelines and reports [39] [38].