Secular vs. Religious Bioethics: Foundations, Applications, and Resolutions for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comparative analysis of the foundational principles and methodological applications of secular and religious bioethical traditions.

Secular vs. Religious Bioethics: Foundations, Applications, and Resolutions for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of the foundational principles and methodological applications of secular and religious bioethical traditions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the distinct epistemological roots of these frameworks, from secular principlism and moral bricolage to the doctrines of Abrahamic faiths. The analysis extends to practical application in clinical and research settings, tackles persistent conflicts such as beginning-of-life and end-of-life issues, and proposes integrative models for ethical deliberation. The goal is to equip biomedical professionals with the understanding necessary to navigate ethical dilemmas in a pluralistic world, fostering both ethical integrity and innovative progress.

Mapping the Ethical Landscape: Core Philosophies of Secular and Religious Bioethics

The field of bioethics represents a critical arena where moral philosophy meets practical decision-making in medicine and scientific research. Within this domain, a fundamental debate has emerged regarding the very nature and foundations of bioethical reasoning. This guide examines the central controversy: whether secular principlism constitutes an emerging moral tradition in its own right or represents a problematic departure from more established ethical foundations. This question carries significant implications for researchers and drug development professionals who must navigate ethical frameworks in their work, particularly as technological advancements in areas like artificial intelligence (AI) accelerate the pace of biomedical innovation [1]. The debate intersects directly with research ethics, influencing how guidelines are formulated for clinical trials, data privacy, and the implementation of new technologies.

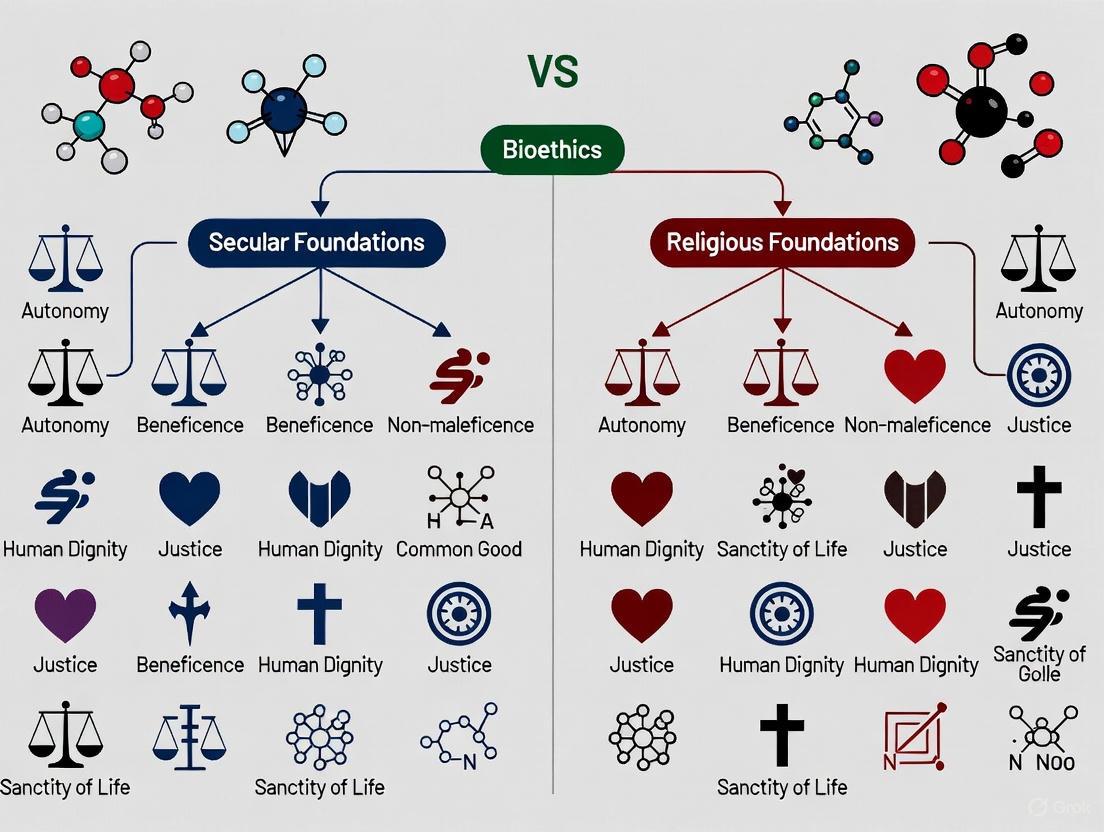

At the heart of this discussion lies secular principlism, often associated with Tom Beauchamp and James Childress's four-principle approach (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice), which has become a dominant framework in contemporary bioethics [2]. Critics and proponents alike are now questioning whether this framework has evolved from a mere methodological tool into a substantive moral tradition with its own distinct history, practices, and community of inquirers [3] [4]. Meanwhile, religious influences in bioethics, though historically foundational, have been increasingly marginalized in mainstream public bioethical discourse, leading to tensions about the sources of moral authority in pluralistic societies [5].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing perspectives, analyzing their core methodological approaches, their claims to moral authority, and their practical implications for biomedical research and drug development. By examining the theoretical frameworks and their applications, we aim to equip professionals with a nuanced understanding of how these ethical foundations shape research paradigms and policy decisions.

Analytical Framework: Core Concepts and Definitions

To navigate the complex debate between secular principlism and religious bioethics, it is essential to first establish clear definitions of the key concepts at play. The table below delineates the central terminology required for this analysis.

Table: Core Conceptual Definitions in the Bioethics "Moral Tradition" Debate

| Concept | Definition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Secular Principlism | A dominant framework in bioethics centered on four core principles: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice [2]. | Methodological focus; appeals to public reason; often described as a "common morality" framework. |

| Moral Tradition | A historically extended, socially embodied argumentative discourse through which a community of inquirers shares beliefs, practices, history, and canonical texts [3] [6]. | Historical continuity; shared narratives; community standards; canonical texts. |

| Moral Bricolage | A methodological approach that takes stock of ethical questions and uses available conceptual resources from various traditions to create solutions [6]. | Pragmatic; eclectic; draws from multiple sources (philosophies, theologies, law). |

| Public Reason | A shared framework for justifying political and ethical decisions without resorting to comprehensive personal doctrines, requiring arguments to be justifiable to all rational persons [5]. | Seeks neutrality; aims for inclusivity in pluralistic societies. |

| Religious Bioethics | Ethical deliberation grounded in the doctrines, teachings, and authority of religious traditions [5]. | Doctrinally based; draws on religious authority; may reference divine commands or theological concepts. |

Comparative Analysis: Secular Principlism as a Moral Tradition

The Emergence Thesis and Its Mechanisms

A significant development in contemporary bioethics is the argument that secular bioethics is evolving from a mere methodological approach into a substantive moral tradition. Proponents of this view, as noted in the Journal of Medical Ethics, reject the notion that bioethics should be limited to analyzing problems or clarifying concepts without offering substantive guidance. They also dismiss Enlightenment accounts based on universal, neutral rational standards. Instead, they posit that bioethics, once a discourse for various moral traditions to engage with ethical challenges, is now becoming "an emerging content-full moral tradition in its own right" [3] [4].

The mechanism driving this evolution is often described as moral bricolage. This process involves tackling pressing ethical questions by drawing upon the available conceptual resources from diverse sources—including philosophy, theology, and law—and reworking them into coherent solutions. Through repeated exercises of building consensus on specific issues, participants in bioethical discourse gradually develop shared beliefs, practices, and historical narratives. These accumulating consensus documents and canonical texts thus form the foundation of an emerging tradition [6].

The Case Against the "Moral Tradition" Designation

Critics challenge the characterization of secular bioethics as a moral tradition, arguing that this claim represents a form of intellectual hegemony. From this perspective, presenting secular bioethics as a established tradition functions as a "way of stacking the deck" in moral debates, potentially marginalizing alternative viewpoints [3]. These critics emphasize that unlike historically grounded religious traditions, secular bioethics lacks the deep historical roots and shared metaphysical commitments that characterize genuine moral traditions.

A central criticism focuses on the problem of moral authority. Detractors argue that because secular bioethics rejects both religious authority and universal rational foundations, it lacks a coherent basis for its normative claims. The field is described as "purely subjective," driven by philosophers, professors, doctors, and lawyers who offer opinions but lack any licensed or authoritative standing [3]. This subjectivity becomes problematic when the consensus reached within this community is presented as binding for public policy or for professionals who fundamentally disagree with its conclusions, such as in debates over medical conscience and euthanasia [3].

Experimental & Methodological Approaches in Ethical Analysis

Research Design in Implementation Science

While bioethics is primarily a philosophical discipline, its claims and frameworks can be empirically tested through implementation science, which studies how to effectively adopt clinical practices in real-world settings. The table below summarizes key research designs relevant to testing the application of ethical frameworks.

Table: Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs in Implementation Ethics Research

| Research Design | Key Features | Application in Ethics Research | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Random assignment; manipulation of independent variable [7]. | Testing effectiveness of specific ethics implementation strategies. | High internal validity; minimizes confounding. | Risk of contamination; may lack generalizability. |

| Cluster-Randomized Trial | Randomization at group level (clinics, sites) [7]. | Evaluating ethics training programs where individual randomization is impractical. | Reduces contamination between groups. | Requires complex analytic models; few sites can cause confounding. |

| Sequential, Multiple-Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART) | Multistage randomization based on ongoing response [7]. | Optimizing sequences of ethics interventions adapted to ongoing needs. | Informs adaptive implementation strategies. | Increased complexity and cost. |

| Stepped Wedge Design | All participants receive intervention in staggered fashion [7]. | Phased rollout of ethics guidelines across multiple sites. | Allows within-site comparisons; useful when intervention is deemed beneficial. | Complex statistical analysis; potential for time-varying confounders. |

Ethical Framework Application in AI-Driven Drug Development

The emergence of AI in drug development provides a concrete context for comparing the application of different ethical frameworks. Researchers have developed a specific ethical evaluation framework centered on the four principles of autonomy, justice, non-maleficence, and beneficence, which are applied across three critical stages of AI-driven drug development [1].

The diagram below illustrates how this principlist framework is operationalized throughout the AI drug development pipeline, mapping ethical principles to specific evaluation dimensions and their corresponding risk points.

This application of principlism demonstrates its methodological approach: translating abstract principles into concrete operational standards across a specific technological domain. The framework addresses particular deficiencies in general AI ethics guidelines by creating quantifiable operational standards for the entire drug development lifecycle [1].

The Religious-Secular Divide: Comparative Foundations

Philosophical and Methodological Differences

The debate between secular and religious approaches to bioethics represents a fundamental divide in how moral knowledge is justified and applied. The following table compares their distinct foundations and methodological approaches.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Secular and Religious Bioethics Foundations

| Aspect | Secular Bioethics | Religious Bioethics |

|---|---|---|

| Moral Foundation | Public reason; common morality [5]. | Religious doctrines and teachings [5]. |

| Epistemological Basis | Reflective equilibrium; democratic discourse [2]. | Religious authority; divine command; sacred texts. |

| Primary Methodology | Moral bricolage; consensus-building [6]. Doctrinal interpretation; theological reasoning. | |

| Scope of Application | Pluralistic public discourse [5]. | Faith communities; individuals with shared beliefs. |

| View of Principles | Guidelines emerging from human experience [2]. | Derivative of fundamental religious commitments. |

| Language Function | Tool for public justification [2]. | Expression of divinely revealed truths. |

The Challenge of Pluralism and Inclusivity

A central point of contention in this debate concerns how each approach handles moral pluralism. Secular bioethics, particularly through the framework of public reason, requires that ethical justifications be accessible to all rational persons regardless of their religious commitments. This approach aims to create an inclusive dialogue where religious and non-religious perspectives can coexist through shared reasoning [5]. However, this very framework obligates religious individuals to translate their convictions into generally acceptable arguments, which some religious scholars argue marginalizes their deeply held beliefs [5].

Proponents of religious inclusion in bioethics, such as Joseph Tham and Aasim Padela, argue that excluding religious perspectives leads to a narrow and incomplete understanding of ethical issues. They contend that religious traditions offer rich sources of moral wisdom and time-tested ethical frameworks that can enrich bioethical discourse [5]. The concept of pluriversality has been proposed as a potential middle ground, advocating for a world where different cultural and religious knowledge systems coexist without being subsumed under a singular universal framework [5]. However, critics question whether this approach can overcome ethical inconsistencies and maintain alignment with established human rights frameworks when religious doctrines conflict with them.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions: Conceptual Toolkit

Just as laboratory research requires specific reagents and tools, comparative analysis in bioethics relies on distinct conceptual frameworks and methodologies. The table below outlines this essential "research toolkit" for investigating the moral tradition debate.

Table: Essential Conceptual Toolkit for Bioethics Foundation Research

| Research 'Reagent' | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Public Reason Framework | Provides justifications accessible to all rational persons [5]. | Formulating public policy on controversial bioethical issues. |

| Moral Bricolage Method | Creates ethical solutions from diverse conceptual resources [6]. | Developing consensus statements on emerging technologies. |

| Principlist Framework | Offers mid-level principles for ethical analysis [1] [2]. | Clinical ethics consultation; research ethics review. |

| Comparative Tradition Analysis | Examines how different traditions approach specific ethical questions [8]. | Understanding cross-cultural perspectives in global bioethics. |

| Consensus-Building Protocols | Formal processes for reaching agreement among diverse stakeholders [6]. | Ethics guideline development; institutional policy creation. |

The debate over whether secular principlism constitutes a moral tradition carries significant practical implications for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals. The resolution of this theoretical question directly influences which ethical frameworks govern research protocols, clinical trial design, and the implementation of emerging technologies like AI in drug discovery [1].

For professionals in this field, understanding this contested terrain is crucial for navigating the ethical dimensions of their work. Each approach offers distinct resources for addressing novel ethical challenges: secular principlism provides a framework for public justification in pluralistic environments, while religious perspectives offer connection to deeply rooted moral traditions that resonate with significant portions of the global population. As bioethics continues to evolve as a discipline, the interaction between these frameworks will likely shape ethical guidelines for future scientific innovation, making this debate particularly relevant for those at the forefront of biomedical research.

The integration of religious doctrines into bioethical discourse represents a critical frontier in medical research and policy development. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals operating in increasingly globalized environments, understanding the foundational ethical frameworks of major religious traditions is essential for designing culturally sensitive studies and implementing equitable healthcare solutions. The Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Catholicism, and Islam—collectively influence the moral frameworks of more than half of the world's population, offering centuries-old wisdom developed through scriptural interpretation and theological reasoning [9]. These traditions provide distinctive perspectives on fundamental questions regarding the origin of human life, the protection of vulnerable populations, and the ethical boundaries of scientific intervention in natural processes.

Recent bioethical conferences, including the World Congress of Bioethics held in Qatar in 2024, have highlighted the ongoing tension between religious and secular approaches to bioethics, sparking important conversations about how to integrate diverse value systems in global health contexts [5]. This analysis offers a structured comparison of doctrinal positions from Islam, Catholicism, and Judaism on key bioethical issues relevant to pharmaceutical research and development, providing a resource for professionals navigating this complex landscape. By understanding these perspectives, researchers can foster more inclusive dialogue and develop methodologies that respect diverse patient populations while advancing scientific knowledge.

Doctrinal Positions on Key Bioethical Issues

Comparative Table of Doctrinal Positions

Table 1: Doctrinal positions of Abrahamic traditions on key bioethical issues

| Bioethical Issue | Islamic Perspectives | Catholic Perspectives | Jewish Perspectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation of Bioethics | Grounded in maslahah (public good) and Maqasid al-Shariah (objectives of Islamic law) [5] [10] | Stresses relational love and sacramentality [5] | Emphasizes covenantal responsibility [5] |

| Assisted Reproduction | Permitted within marriage; gamete donation controversial [9] | Generally prohibited; violates marital unity and natural law [9] [5] | Broadly permitted to fulfill commandment "be fruitful and multiply"; may be mandatory for infertile couples [9] |

| Gamete Donation | Generally prohibited as it confuses lineage [9] | Prohibited as it severs procreation from marital union [9] | Orthodox: prohibited as adultery; Reform: permitted with rabbinic guidance [9] |

| Embryo Status & Research | Early embryo respected; research permitted with restrictions [9] | Human dignity from conception; embryo research prohibited [9] [5] | Soul enters at 40 days; pre-implantation research generally permitted [9] |

| Role of Science | Scientific advancement complements God's creative work [9] | Cautious engagement; technology must respect natural law [9] | Humans partner with God in creation; technology positively viewed [9] |

Conceptual Framework for Religious Bioethical Reasoning

Diagram Title: Religious Bioethical Reasoning Framework

This diagram illustrates the general framework through which Abrahamic traditions derive specific bioethical positions. Each tradition begins with its scriptural sources and develops theological principles, which are then applied through distinctive interpretive methods to contemporary scientific challenges, resulting in formulated bioethical positions [9] [5].

Comparative Analysis of Doctrinal Foundations

Islamic Bioethical Framework

Islamic bioethics derives from the Quran, Sunnah, and centuries of jurisprudential reasoning, with contemporary scholarship addressing novel biomedical technologies through the lens of Maqasid al-Shariah (the higher objectives of Islamic law) [10]. Scholars like Aasim Padela have advocated for incorporating Islamic viewpoints into bioethical discourse, arguing that excluding religious perspectives marginalizes significant portions of the global population [5]. The principle of maslahah (public interest) serves as a crucial tool for addressing new bioethical challenges not explicitly mentioned in primary sources, allowing for flexible application while maintaining theological integrity [5].

On specific issues like assisted reproduction, Islamic perspectives generally permit techniques that preserve genetic lineage and marital boundaries. Gamete donation is typically prohibited due to concerns about confusing lineage, while in vitro fertilization between spouses is widely accepted [9]. The embryo is accorded moral status from early development, though not necessarily full human rights, allowing for some forms of research under specific conditions [9]. This balanced approach demonstrates how Islamic bioethics seeks to both embrace scientific progress and preserve fundamental moral values derived from revelation.

Catholic Bioethical Framework

Catholic bioethics is characterized by its consistent ethic of life, grounded in natural law theory and theological teachings about human dignity. The tradition emphasizes relational love and sacramentality, viewing the human person as created in God's image and deserving of protection from conception to natural death [5]. This foundational principle informs the Catholic perspective on assisted reproduction, which generally prohibits techniques that separate the unitive and procreative dimensions of marital intimacy [9].

The Catholic tradition maintains that human dignity is inherent from the moment of conception, resulting in strict limitations on embryonic research and any procedures that may harm or destroy human embryos [9] [5]. This position reflects the tradition's commitment to protecting the most vulnerable human lives, even at the expense of potential scientific advancements. Scholars like Joseph Tham have argued against the marginalization of religious viewpoints in bioethics, contending that excluding Catholic perspectives leads to an impoverished understanding of ethical issues in healthcare and research [5].

Jewish Bioethical Framework

Jewish bioethics operates within the framework of Halakha (Jewish law), which provides a structured approach to analyzing new technological developments through scriptural interpretation and rabbinic reasoning. The tradition emphasizes covenantal responsibility, viewing humans as partners with God in the ongoing work of creation and healing [5]. This collaborative understanding of the human-divine relationship creates a generally positive orientation toward scientific and medical innovation.

The commandment to "be fruitful and multiply" (Genesis 1:28) holds central importance in Jewish bioethical deliberations about assisted reproduction [9]. This imperative often leads to broad permission of reproductive technologies, with some authorities considering treatment mandatory for infertile couples. Jewish law incorporates a developmental view of embryonic status, with the soul not believed to enter the body until forty days after conception, allowing greater flexibility for pre-implantation research and embryo selection [9]. This approach demonstrates how Jewish bioethics balances respect for potential life with the positive value placed on bringing new life into the world.

Research Methodology and Analytical Approaches

Comparative Religious Bioethics Methodology

Diagram Title: Comparative Analysis Workflow

Research in comparative religious bioethics typically follows a structured methodology beginning with identification of authoritative scriptural sources and interpretive traditions within each faith [9]. Scholars then analyze these texts to extract core theological principles and ethical frameworks, which are applied to specific biomedical cases [5]. The comparative stage identifies areas of convergence and divergence between traditions, ultimately informing policy development that respects pluralistic values while upholding ethical standards [9] [5].

Table 2: Key research reagents and resources for religious bioethics scholarship

| Research Resource | Function & Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Religious Texts | Foundational sources of doctrinal authority | Quran, Bible, Talmud, Torah [9] |

| Contemporary Religious Scholarship | Interpretation and application to modern technologies | Islamic: Padela; Catholic: Tham; Jewish: Feinstein, Tendler [9] [5] |

| Academic Bioethics Literature | Secular ethical frameworks and critical analysis | Journals, conference proceedings [5] |

| Case Studies & Responsa | Applied analysis of specific biomedical scenarios | Rabbinic responsa on ART; Catholic ethical directives [9] |

| Institutional Policies & Guidelines | Formal positions of religious authorities on medical ethics | Vatican directives; Islamic Fiqh Council opinions [9] |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that while Abrahamic traditions share common concerns for protecting human life and dignity, they diverge significantly in their approaches to applying these principles to contemporary biomedical challenges. These differences reflect varying theological anthropologies, interpretive methods, and understandings of humanity's role in creation. For drug development professionals and researchers, this comparative framework offers valuable insights for designing culturally competent research protocols, anticipating ethical concerns in diverse patient populations, and fostering inclusive dialogue about the moral dimensions of scientific progress.

The ongoing debate between religious and secular approaches to bioethics highlights the continued relevance of these traditions in shaping global health policy [5]. Rather than representing obstacles to scientific progress, religious bioethical frameworks offer rich moral heritage and time-tested wisdom that can contribute to more humane and equitable medical care. As biomedical technologies continue to advance, understanding these foundational perspectives will be essential for navigating the complex intersection of science, ethics, and faith in the 21st century.

The field of bioethics increasingly operates at the intersection of secular and religious frameworks, creating fundamental tensions between universalist principles that claim cross-cultural validity and faith-based approaches grounded in specific revelation traditions. This epistemological divide represents one of the most significant challenges in contemporary bioethical discourse, particularly for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating diverse ethical landscapes. Understanding these contrasting foundations is essential for productive collaboration in global health contexts and multinational research initiatives. This analysis examines the epistemological roots, methodological approaches, and practical implications of these competing frameworks to provide researchers with a structured understanding of how different ethical systems approach complex bioethical dilemmas.

Theoretical Foundations and Epistemological Frameworks

Universalist Principles in Bioethics

Universalist approaches in bioethics seek to establish ethical frameworks that transcend particular cultural or religious traditions, aiming for broadly applicable principles grounded in rational discourse. The dominant universalist framework in contemporary bioethics is principism, which organizes ethical analysis around four core principles: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice [11]. This approach attempts to create a common language for ethical deliberation across different value systems by focusing on procedural rationality and shared human values rather than specific metaphysical commitments.

The philosophical underpinnings of universalist bioethics trace primarily to Enlightenment rationalism and Kantian deontology, emphasizing human dignity, rights, and the capacity for reasoned moral deliberation independent of religious revelation. Proponents argue that such frameworks are necessary for pluralistic societies and global bioethical standards, particularly in contexts like international research ethics, pandemic response planning, and emerging technology governance. However, critics contend that universalist approaches often mask particular Western cultural assumptions and fail to adequately accommodate diverse moral traditions [12].

Recent developments in universalist thought include pluriversalism, which attempts to acknowledge cultural and religious diversity while maintaining cross-cultural ethical standards. This framework espouses "bioethical discourse grounded in civility, respect for law, justice, non-domination, and toleration" [12]. Yet this approach faces significant challenges regarding ethical consistency and reconciliation with established human rights frameworks when religious perspectives make claims that conflict with liberal individual rights.

Faith-Based Revelation in Bioethics

Faith-based approaches to bioethics derive their epistemological foundations from religious traditions and sacred texts rather than universal reason. These frameworks ground ethical reasoning in divine revelation, religious authority, and communal traditions that define concepts of human flourishing, moral obligations, and the proper limits of technological intervention. Unlike universalist approaches that prioritize autonomous rational deliberation, faith-based ethics typically emphasizes duties to God, community, and created order.

Major religious traditions provide comprehensive moral frameworks that address bioethical concerns through theological anthropology (understanding human nature), moral cosmology (understanding the purpose and order of creation), and specific moral commands derived from sacred texts and interpretive traditions. For example, Islamic bioethics integrates Quranic revelation, Prophetic traditions, and centuries of juridical scholarship to address contemporary medical dilemmas [10]. Similarly, Christian bioethics draws from biblical texts, theological traditions, and natural law reasoning to develop moral positions on issues from beginning-of-life to end-of-life concerns.

The methodological approach of faith-based bioethics typically involves hermeneutical engagement with authoritative texts, casuistical application of established principles to new circumstances, and communal discernment rather than individual autonomous decision-making. These approaches recognize moral limits to technological intervention based on concepts of divine sovereignty, natural order, or human dignity understood through theological lenses. For researchers, understanding these foundations is crucial when engaging religious communities or working in contexts where religious values significantly influence healthcare policies and research ethics.

Table: Comparative Epistemological Foundations

| Aspect | Universalist Principles | Faith-Based Revelation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source of Knowledge | Human reason, empirical evidence, rational discourse | Divine revelation, sacred texts, religious authority |

| Moral Justification | Principles derived through logical consistency and cross-cultural validation | Commands and values revealed through sacred sources and tradition |

| Scope of Application | Theoretical global applicability regardless of cultural context | Primarily within religious community, with varying engagement with pluralistic society |

| Key Conceptual Frameworks | Principism (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice) | Theological anthropology, natural law, divine command theory |

| Methodological Approach | Rational deliberation, procedural ethics, consensus-building | Hermeneutics, casuistry, communal discernment |

Methodological Approaches and Analytical Frameworks

Research Methodologies for Ethical Analysis

The contrasting epistemological foundations of universalist and faith-based approaches necessitate different methodological frameworks for ethical analysis. Understanding these methodologies is essential for researchers conducting ethical analyses or engaging with diverse ethical perspectives in their work.

Universalist bioethics employs several characteristic methodological approaches. Principle-based analysis systematically applies the four principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice to ethical dilemmas, often using them as a framework for case analysis [11]. Empirical methods in bioethics incorporate quantitative and qualitative research—including surveys, content analysis, focus groups, and individual interviews—to understand ethical dimensions of healthcare practices and policies [11]. These methodological approaches prioritize transparency, replicability, and rational justification accessible to people across different cultural and religious backgrounds.

Faith-based methodologies employ distinctly different approaches to ethical analysis. Textual hermeneutics involves careful interpretation of sacred texts and religious traditions to derive ethical guidance for contemporary issues. Tradition-based reasoning engages with centuries of religious scholarship and ethical deliberation within the tradition, applying established principles to new circumstances through analogical reasoning. Virtue ethics emphasizes character formation and spiritual development as foundational to ethical discernment, focusing on the moral qualities of the decision-maker rather than just the act itself. These methodologies recognize religious authority and spiritual discernment as valid ways of knowing, complementing or sometimes challenging purely rational approaches.

Table: Comparative Analytical Methodologies

| Methodological Approach | Universalist Application | Faith-Based Application |

|---|---|---|

| Case Analysis | Systematic application of mid-level principles | Casuistical reasoning from paradigmatic cases in religious tradition |

| Textual Analysis | Critical engagement with philosophical and legal texts | Hermeneutical engagement with sacred texts and interpretive traditions |

| Empirical Inquiry | Social science research on attitudes and outcomes | Study of religious community practices and beliefs |

| Deliberative Process | Democratic discourse seeking overlapping consensus | Communal discernment respecting religious authority |

| Normative Justification | Appeals to shared rationality and public reason | Appeals to religious authority and revealed truth |

Conceptual Mapping of Ethical Frameworks

The diagram below visualizes the logical relationships and decision pathways within universalist and faith-based bioethical frameworks, highlighting their contrasting structures and focal points:

This conceptual mapping illustrates how universalist frameworks employ a linear analytical process focused on principle application, while faith-based approaches employ a hermeneutical circle engaging authoritative sources and interpretive communities. For researchers, understanding these different pathways is essential when anticipating how various stakeholders will approach ethical dilemmas in research settings.

Experimental Protocols for Ethical Analysis

Protocol 1: Principism-Based Ethical Analysis

The principism framework developed by Beauchamp and Childress provides a systematic methodology for ethical analysis that dominates contemporary secular bioethics [11]. This experimental protocol outlines a standardized approach for applying this framework to bioethical dilemmas, particularly useful for research ethics committees and policy development groups.

Materials and Methodology: The primary materials required include the case description with all relevant factual details, reference materials on the four principles (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice), and documentation of relevant legal and policy contexts. The methodology proceeds through six systematic phases: (1) Case Fact-Finding - gathering all relevant medical, social, and contextual information; (2) Principle Identification - determining which principles are relevant to the case; (3) Specification - translating abstract principles into concrete moral norms for the specific context; (4) Balancing - resolving conflicts between principles through weighting and prioritization; (5) Justification - providing reasoned arguments for the chosen resolution; and (6) Documentation - recording the analytical process and outcome for transparency and review.

Application Context: This methodology is particularly valuable in pluralistic settings like institutional review boards, hospital ethics committees, and public policy development, where participants may hold diverse moral commitments. The framework provides a common vocabulary and structured process for ethical deliberation without requiring agreement on foundational metaphysical questions. Research has shown this approach increases systematic reasoning and transparency in ethical decision-making, though critics note it may obscure deeper philosophical disagreements and cultural biases embedded in the principles themselves.

Protocol 2: Religious Tradition-Based Ethical Analysis

Faith-based ethical analysis follows a different experimental protocol grounded in engagement with religious sources and interpretive communities. This protocol outlines a systematic approach for conducting ethical analysis within a religious tradition, using Islamic bioethics as exemplified by Dr. Padela's work [10] as a model, though adaptable to other religious traditions.

Materials and Methodology: Required materials include sacred texts (e.g., Quran, Bible, Torah), interpretive traditions (commentaries, scholarly works), case precedents from the religious tradition, and consultation with religious authorities. The methodology involves five iterative phases: (1) Textual Exegesis - close reading of relevant scriptural passages; (2) Tradition Engagement - study of historical interpretations and applications; (3) Principle Extraction - identifying overarching ethical principles from specific texts and cases; (4) Contemporary Application - applying derived principles to modern biomedical contexts through analogical reasoning; and (5) Communal Validation - testing interpretations with religious community and authorities.

Application Context: This methodology is essential when researching or implementing healthcare interventions in religious communities, developing culturally sensitive research protocols, or understanding religious objections to certain medical technologies. The protocol recognizes that within religious traditions, ethical reasoning is not merely an individual cognitive process but a communal practice of discernment. For researchers, understanding this process facilitates more meaningful engagement with religious perspectives rather than dismissing them as simply irrational or obstructive.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Analysis

The table below details key conceptual tools and resources essential for conducting rigorous research in comparative bioethics, particularly when analyzing universalist and faith-based approaches:

Table: Essential Research Resources in Comparative Bioethics

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Principism Framework | Structured ethical analysis using four core principles | Secular bioethics deliberation, policy development, clinical ethics consultation |

| Religious Textual Databases | Access to sacred texts and traditional commentaries | Understanding faith-based perspectives on specific bioethical issues |

| Empirical Research Methods | Quantitative and qualitative study of ethical beliefs and practices | Investigating stakeholder perspectives, evaluating ethical outcomes [11] |

| Hermeneutical Analysis Protocols | Systematic interpretation of religious texts and traditions | Faith-based bioethics analysis, engaging religious communities |

| Comparative Ethics Rubrics | Structured comparison of different ethical frameworks | Cross-cultural research, multinational policy development |

| Case Repository Databases | Collections of paradigmatic cases with analyses | Ethics education, case-based reasoning, precedent consultation |

These research tools enable systematic investigation of the epistemological roots and practical implications of different bioethical frameworks. For researchers working in global health or multinational clinical trials, familiarity with these resources is essential for navigating diverse ethical landscapes and anticipating potential conflicts between universalist aspirations and particular religious commitments.

Comparative Analysis and Research Implications

Empirical Findings and Conceptual Tensions

Research reveals significant tensions between universalist and faith-based approaches in bioethics, with important implications for scientific practice and policy development. The 2024 World Congress of Bioethics in Qatar highlighted these tensions, particularly regarding the proper role of religious values in bioethical discourse [12]. Proceedings demonstrated persistent challenges in reconciling universal human rights frameworks with religious traditions that may hold divergent views on issues like gender equality, sexual orientation, or religious authority.

Empirical studies of bioethical deliberation reveal that universalist frameworks tend to prioritize individual autonomy, informed consent, and personal liberty, while faith-based approaches often emphasize community wellbeing, traditional values, and moral constraints on individual choice. These differences manifest practically in areas like end-of-life decision-making, reproductive technologies, and genetic manipulation. For example, where universalist frameworks might focus primarily on patient self-determination in cessation of treatment decisions, religious approaches might emphasize the sanctity of life or divine sovereignty over life and death.

The conceptual mapping below illustrates how these epistemological differences manifest in practical decision-making contexts, particularly showing the different weighting given to various ethical considerations:

Research Applications and Practical Implications

For researchers and drug development professionals, these epistemological differences have significant practical implications. Research protocol development must navigate tensions between universal ethical standards and particular religious values, especially in multinational trials. Informed consent processes may require adaptation to accommodate different understandings of autonomy, family authority, and religious obligations. Emerging technologies like genetic engineering, artificial intelligence in healthcare, and neuroenhancement present particularly challenging frontiers where universalist and faith-based perspectives often diverge sharply.

Successful navigation of these tensions requires methodological flexibility and conceptual clarity about the epistemological foundations of different ethical positions. Researchers should implement structured approaches to ethical analysis that explicitly acknowledge their underlying frameworks while remaining open to constructive engagement with alternative perspectives. This includes developing capacity for religious literacy in research ethics, understanding how different traditions approach fundamental questions of human dignity, moral authority, and the proper scope of technological intervention.

The epistemological divide between universalist principles and faith-based revelation represents a fundamental tension in contemporary bioethics with significant implications for research practice and policy development. Universalist approaches grounded in rational discourse and principle-based analysis provide important frameworks for pluralistic deliberation but risk underestimating the legitimate role of religious perspectives in ethical reasoning. Faith-based approaches rooted in divine revelation and religious tradition offer comprehensive moral frameworks for their communities but face challenges in engaging pluralistic discourse without either dilution or domination.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, navigating this landscape requires both conceptual clarity about these contrasting epistemological foundations and practical methodological skills for engaging diverse ethical perspectives. Rather than seeking simplistic resolution of these tensions, productive way forward involves developing capacity for ethical bilingualism—understanding and respecting both universalist and faith-based approaches while clearly acknowledging their distinctive epistemological commitments. This approach fosters more meaningful engagement with ethical diversity while maintaining intellectual integrity about fundamental differences that cannot be easily reconciled through procedural solutions alone.

The Emergence of 'Moral Bricolage' in Secular Public Bioethics

This analysis examines the conceptual framework of 'moral bricolage' as a defining characteristic of contemporary secular bioethics. Drawing upon recent scholarly literature, we explore how this approach synthesizes diverse philosophical, theological, and legal traditions to address complex ethical challenges in medicine and life sciences. By comparing the methodological foundations of secular and religious bioethics, we identify distinctive strengths and limitations of each paradigm, with particular attention to their applications in pharmaceutical development and clinical practice. The findings demonstrate that moral bricolage represents both an adaptive response to moral pluralism and a potentially contested authority in public bioethics discourse.

The field of secular bioethics operates within a context of significant moral pluralism, where diverse value systems coexist without a shared metaphysical foundation. Moral bricolage has emerged as a central theoretical framework describing how bioethicists navigate this complexity by creatively assembling available conceptual resources from multiple traditions to address contemporary ethical challenges [6]. This approach stands in contrast to both proceduralist models that merely analyze moral problems without offering substantive guidance, and Enlightenment models that seek universal rational principles undeniable by any reasonable person [13].

The theoretical underpinnings of moral bricolage respond directly to Alasdair MacIntyre's "disquieting suggestion" that contemporary moral language suffers from such profound disorder that securing authoritative moral guidance may be impossible [6]. Jeffrey Stout's conceptualization of moral bricolage in Ethics After Babel offers a constructive alternative to MacIntyre's pessimistic assessment, suggesting that ethical guidance can be developed through a process of gathering and reworking available conceptual resources from various traditions—including philosophies, theologies, and legal frameworks [6]. This methodological approach has gained particular traction in public bioethics, which aims to provide moral guidance on questions of public policy, research ethics, and clinical practice in pluralistic societies [6].

Table 1: Theoretical Foundations of Moral Bricolage

| Conceptual Element | Description | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|

| Moral Pluralism | Context of diverse, competing moral frameworks without shared metaphysical foundations | [14] |

| Conceptual Resource Gathering | Drawing upon philosophies, theologies, laws from multiple traditions | [6] |

| Creative Reconfiguration | Adapting and reworking resources to address novel bioethical challenges | [6] |

| Tradition Formation | Developing shared practices, histories, and canonical texts through repeated application | [6] |

Comparative Analysis: Secular versus Religious Bioethical Foundations

The emergence of moral bricolage in secular bioethics must be understood in contrast to religious approaches to bioethical reasoning. Where religious bioethics typically begins with established theological premises and authoritative texts, secular bioethics employs pragmatic integration of multiple moral frameworks without privileging specifically religious sources [14]. This fundamental methodological difference generates distinctive strengths and limitations for each approach.

Secular Bioethics: Universalism and Its Constraints

Secular bioethics is characterized by its aspiration to moral universalism—the development of ethical frameworks acceptable to individuals regardless of religious affiliation or ideological commitment [14]. This universalist ambition manifests in bioethics' foundational precept of "respect for persons," which demands that religious beliefs not be dismissed as merely irrational while simultaneously making it difficult to include religion as a serious element in moral decision-making [14]. This tension inevitably leads to what one analyst terms the "ghettoization" of religion, whereby we find distinct Catholic, Jewish, and Islamic bioethics traditions operating alongside but separate from mainstream secular bioethics [14].

A significant limitation of secular bioethics identified by critics is its movement from "thick" to "thin" ethical reasoning [14]. Early bioethics engaged with substantive questions about human nature and the meaning of life, drawing on both theological and philosophical insights. In its contemporary bureaucratic form, however, bioethics has largely shifted toward thinner, more formal concerns with guidelines and regulations [14]. This thinning process has created a conceptual vacuum regarding existential questions, particularly those surrounding suffering and its meaning. As anthropologist Arthur Kleinman observes, bioethics has largely ceded inquiries into the nature and meaning of suffering to religious traditions, with many professional ethical volumes not even including "suffering" in their indices [14].

Religious Bioethics: Teleology and Tradition

Religious approaches to bioethics differ fundamentally in their retention of teleological perspective—concern with ultimate purpose and meaning that transcends immediate practical considerations [14]. Where secular bioethics typically brackets questions of ultimate meaning, religious frameworks directly address what Kleinman identifies as patients' struggles "to make sense of illness with respect to great cultural codes that offer coherent interpretations of experience" [14]. This teleological orientation enables religious bioethics to engage with what Cassell identifies as the "paradox of suffering"—the recognition that while suffering is inherently negative, it can also reveal greater depths of human experience and meaning, leading to enriched understanding and greater concern for others [14].

The historical development of Western bioethics further complicates the secular-religious distinction. As scholar Yusuf Lenfest notes, the methods of ethical analysis dominant in secular bioethics are themselves "a direct result of a particular European and Western epistemology, which, in turn, has its own Christian origins" [15]. The theories that emerged from the Enlightenment represented a "secularization of the Christian ethic" rather than a complete break from religious moral reasoning [15]. This historical continuity suggests that the relationship between secular and religious bioethics may be more complex than a simple binary opposition.

Table 2: Key Distinctions Between Secular and Religious Bioethics

| Dimension | Secular Bioethics | Religious Bioethics |

|---|---|---|

| Moral Foundation | Reason, principles, consensus | Revelation, tradition, authority |

| Scope of Concern | Primarily "thin" procedural and regulatory questions | Includes "thick" existential and teleological questions |

| Approach to Suffering | Often ignored or addressed procedurally | Central concern with paradoxical meaning and value |

| Methodology | Moral bricolage, principlism | Textual interpretation, traditional application |

| Community Formation | Emerging professional tradition with shared practices | Established religious communities with shared beliefs |

Moral Bricolage in Practice: Applications to Medicines Development

The theoretical framework of moral bricolage finds practical application in the evolving field of pharmaceutical medicine and medicines development. The increasingly complex nature of medical interventions—particularly advanced therapies like gene and cell treatments—requires collaboration among multidisciplinary teams including medically qualified physicians, natural scientists, molecular biologists, geneticists, device engineers, psychologists, and bioethicists [16] [17]. This professional diversity necessitates ethical frameworks capable of integrating perspectives from multiple disciplinary traditions.

Ethical Frameworks for Multidisciplinary Teams

Traditional ethical guidelines for human subjects research have placed primary responsibility on medically qualified physicians, consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki's statement that "It is the duty of physicians who are involved in medical research to protect the life, health, dignity, integrity, right to self-determination, privacy and confidentiality of personal information of research subjects" [17]. However, the growing complexity of modern drug development challenges this physician-centered model. As one analysis notes, in contemporary multidisciplinary teams, "the physicians work as team members, with special ethical responsibility to care for the well-being of the patients," but may lack the specialized knowledge to fully evaluate all aspects of complex interventions [17].

This recognition has led to the development of expanded ethical frameworks that explicitly address the shared ethical responsibility of all team members in medicines development. The International Federation of Associations of Pharmaceutical Physicians (IFAPP) has updated its International Code of Ethical Conduct to create an International Ethics Framework for Pharmaceutical Physicians and Medicines Development Scientists that encompasses both medically qualified and non-medically qualified professionals [17]. This framework acknowledges that all team members influence outcomes and subject safety, and thus must share ethical responsibility, while recognizing that physicians retain overriding responsibility for subject well-being [17].

Ethical Challenges in Translational Medicine

The process of translational medicine—bridging non-clinical studies with early human trials—illustrates both the necessity and challenges of moral bricolage in pharmaceutical development. Problems with reproducibility in basic science research present significant ethical concerns for subsequent human trials. Studies indicate that only 6% of landmark studies published in prestigious journals provide sufficiently robust data to reliably drive human medicines development programs, with industrial R&D experts reporting inability to reproduce approximately 50% of academic publications on potential therapeutic targets [17].

These reproducibility issues create tangible risks for human subjects, exemplified by tragic phase I trial incidents involving compounds like TGN-1412 and BIA 10-2474 [17]. Addressing these challenges requires ethical integration of expertise across the translational continuum, with academic scientists adopting more rigorous research methods similar to those used in clinical trials, and all team members sharing responsibility for ensuring valid and reliable translation from preclinical to clinical studies [17].

Table 3: Core Conceptual Resources for Moral Bricolage in Bioethics

| Resource Category | Specific Components | Function in Ethical Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Frameworks | Principlism (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice); Virtue ethics; Deontological approaches; Utilitarian calculus | Provide systematic methods for identifying and weighing ethical considerations |

| Theological Traditions | Religious perspectives on suffering; Concepts of human dignity; Teleological understandings of human flourishing | Offer resources for addressing existential questions and meaning |

| Legal/Regulatory Frameworks | Declaration of Helsinki; Belmont Report; National regulations; Professional codes of conduct | Establish minimal standards and procedural requirements |

| Empirical Research Methods | Reproducibility standards; Clinical trial methodologies; Qualitative approaches to suffering | Provide evidence base for ethical evaluation and decision-making |

| Cross-Cultural Perspectives | Islamic bioethics; Jewish medical ethics; Catholic social teaching; Various indigenous knowledge systems | Expand conceptual resources beyond Western frameworks |

Critical Perspectives and Controversies

The claim that secular bioethics constitutes an emerging "moral tradition" has generated significant debate within the field. Critics contend that this characterization represents a form of conceptual hegemony that marginalizes alternative perspectives, particularly religious viewpoints [13]. As one commentator argues, "Public-advocacy-focused secular bioethics is largely progressive politics covered with a veneer of expertise" rather than a genuine moral tradition with deep historical roots [13]. This perspective highlights the relatively recent emergence of bioethics as a formal field of inquiry and the absence of licensing or standardized credentialing for bioethicists.

A particular concern raised by critics involves the potential for orthodoxy enforcement under the guise of consensus development. The example of medical conscience exemptions illustrates this tension, where alleged consensus positions may in reality represent agreements among like-minded bioethicists that impose compliance requirements on professionals with divergent moral commitments [13]. In some jurisdictions, such as Ontario, Canada, policies requiring physicians to provide "effective referral" for services they consider morally objectionable have created significant conflicts for professionals whose ethical frameworks prohibit certain medical interventions [13].

Defenders of the moral tradition concept respond that bioethics has indeed developed shared practices, historical narratives, and canonical texts that constitute a tradition in the sociological sense [6]. They acknowledge ongoing disagreement within the field but see such debate as characteristic of living traditions rather than evidence against tradition status [6]. This perspective views moral bricolage not as arbitrary eclecticism but as a disciplined methodology for addressing novel ethical challenges in rapidly evolving technological contexts.

The emergence of moral bricolage as a characteristic methodology in secular bioethics represents a significant adaptation to the conditions of moral pluralism in contemporary societies. This approach enables practical ethical guidance despite deep metaphysical disagreements by creatively synthesizing resources from multiple traditions. However, this very adaptability raises questions about the epistemic authority of bioethical recommendations and their capacity to address fundamental questions of human meaning and suffering.

For researchers and professionals in pharmaceutical medicine and drug development, recognition of this ethical methodology has practical implications for team composition, training, and ethical oversight. The increasingly multidisciplinary nature of medicines development necessitates ethical frameworks that can integrate diverse professional perspectives while maintaining fundamental commitments to human subject protection and scientific integrity [17]. Future research should explore more systematically how moral bricolage functions in specific drug development contexts and how its creative potential might be balanced against the need for consistent ethical standards across research settings.

The ongoing dialogue between secular and religious approaches to bioethics continues to enrich both traditions, with secular bioethics offering procedures for navigating moral disagreement while religious perspectives maintain vital concerns with ultimate meaning and purpose. Rather than representing competing alternatives, these approaches may function as complementary resources for addressing the complex ethical challenges posed by emerging medical technologies.

From Theory to Practice: Applying Ethical Frameworks in Clinical and Research Settings

In biopharmaceutical development, specification limits are critical numerical limits or ranges that define the acceptable quality of a drug substance or product, serving as the final gatekeeper for market release [18]. Establishing these specifications is not merely a technical exercise but one deeply embedded in ethical reasoning. The process balances the imperative for robust, safe, and efficacious medicines with complex moral considerations about resource allocation, risk, and societal benefit. This article examines how different bioethical frameworks—secular and religious—inform the methodologies for setting acceptance criteria, shaping the underlying values and risk tolerances that guide development decisions. These foundations influence how scientists and regulators define what constitutes a "good" and "acceptable" product, ultimately determining the control strategies for manufacturing processes that affect global patient populations [18].

Comparative Analysis of Secular and Religious Bioethical Frameworks

The field of bioethics provides diverse lenses for moral decision-making. The dominant secular approach and various religious perspectives offer distinct rationales that can influence technical standards.

Table 1: Comparison of Secular and Religious Bioethical Foundations

| Aspect | Secular Bioethics | Religious Bioethics (e.g., Catholic, Islamic, Jewish) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Foundation | Principles derived from public reason, philosophy, and law [5] | Doctrinal teachings, sacred texts, and theological traditions [5] |

| Core Principles | Autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice [19] | Stewardship, care for creation, sanctity of life, common good [20] |

| Moral Authority | Rational justification and evidence accessible to all, irrespective of belief [5] | Religious authority and revealed truths [5] [14] |

| Approach to Specification Setting | Risk-based, probabilistic (e.g., pre-defined out-of-specification probabilities) [18] | Duty-based, emphasizing precaution and the protection of life [20] |

| View on Technology & Innovation | Often embraces technological solutions guided by risk-benefit analysis [5] | Cautious, assessing compatibility with divine order and human dignity [21] |

| Goal in Biopharmaceutical Development | Consistent quality, patient safety, and efficacy through controlled processes [18] | Healing as a moral act, production of medicines aligned with a sacred view of life [20] |

A significant debate in contemporary bioethics revolves around pluriversalism, a framework that seeks to create "a world where many worlds fit" by embracing global cultural and religious diversity [22]. Proponents argue that marginalizing religious perspectives unfairly privileges secular language and methods, making bioethics less relevant to a majority of the world's population that identifies as religious [22]. Critics, however, caution that a pluriversal approach may struggle with significant ethical inconsistencies and can be hard to reconcile with universal human rights, particularly when religious doctrines conflict with principles of equality or individual autonomy [5]. This tension is highly relevant to global biopharmaceutical development, where companies must navigate diverse ethical landscapes to establish universally acceptable product specifications.

Quantitative Methods for Setting Acceptance Criteria

The establishment of specifications relies on robust statistical methods applied to process data. The following quantitative approaches are foundational.

Probabilistic Tolerance Intervals

A common method for setting acceptance criteria involves calculating probabilistic tolerance intervals [23]. This approach acknowledges the uncertainty that arises when estimating the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) from a limited sample of data. Instead of simply using the sample mean ± a multiple of the standard deviation, it makes statements of the form: "We are 99% confident that 99% of the measurements will fall within the calculated tolerance limits" [23]. The size of the multiplier (M) depends on the desired confidence level, the proportion of the population to be covered, and, critically, the sample size. Smaller sample sizes require larger multipliers to account for greater uncertainty [23].

Table 2: Sigma Multipliers (M) for One-Sided Tolerance Intervals (99% Confidence, 99.25% Coverage) [23]

| Sample Size (N) | Sigma Multiplier (M) |

|---|---|

| 10 | 4.43 |

| 30 | 3.65 |

| 62 | 3.46 |

| 100 | 3.36 |

| 200 | 3.23 |

For example, with a sample size of 62, a mean of 245.7 μg/g, and a standard deviation of 61.91 μg/g, the upper specification limit would be calculated as 245.7 + (3.46 * 61.91) = 460 μg/g [23].

Process Capability Indices

Process capability indices are metrics that quantify how consistently a manufacturing process produces outputs within specifications [24]. The most common indices, Cpk and Ppk, compare the spread of the process variation to the width of the specification limits. A higher index value indicates a lower probability of an out-of-specification (OoS) outcome. For a centered process with two-sided specification limits, a Cpk of 1.0 corresponds to an OoS risk of approximately 0.27% [24]. These indices are vital for quantifying process performance and justifying specification limits to regulators.

Advanced and Integrated Approaches

Conventional methods like the ±3 standard deviations (3SD) approach have a key limitation: they reward poor process control (high variation leads to wider, easier-to-meet limits) and punish good control (low variation leads to tighter limits) [18]. A more advanced methodology is Integrated Process Modeling (IPM). In an IPM, each unit operation (e.g., a chromatography step) is described by a statistical model that predicts its output quality based on input material attributes and process parameters [18]. These unit operation models are then linked together. Using Monte Carlo simulation, random variability is incorporated, allowing developers to predict the final drug substance quality and its probability of meeting specifications [18]. This allows for the derivation of specification-driven intermediate acceptance criteria that ensure a pre-defined out-of-specification probability while considering real-world manufacturing variability [18].

Experimental Protocols for Specification Setting

Protocol for Deriving Acceptance Limits Using Tolerance Intervals

This protocol provides a step-by-step method for establishing specification limits based on process data [23].

- Data Collection and Distribution Testing: Collect data from multiple pre-production or early production batches (N > 30 is desirable). Test the data for normality using a statistical test like the Anderson-Darling test. A p-value greater than 0.05 suggests the data is not significantly different from a normal distribution.

- Handle Outliers: Review the data for outliers using a test like Grubb's test. Potential outliers should be investigated for recording errors or special cause variation. They should not be removed without a documented rationale.

- Calculate Sample Statistics: Calculate the sample mean (x̄) and sample standard deviation (s).

- Select Sigma Multiplier: Based on the sample size (N), the desired confidence level (e.g., 99%), and the desired population coverage (e.g., 99.25%), select the appropriate sigma multiplier (M) from a reference table [23].

- Calculate Specification Limit: For a one-sided upper limit: USL = x̄ + M * s. For a one-sided lower limit: LSL = x̄ - M * s. For a two-sided interval, use the appropriate multiplier (MUL) for the range: (x̄ - MUL * s) to (x̄ + MUL * s).

Protocol for an Integrated Process Model (IPM) Case Study

This methodology leverages knowledge across multiple manufacturing steps for a more robust control strategy [18].

- Process Segmentation and Data Generation: Define the unit operations in the manufacturing process (e.g., harvest, capture chromatography, viral inactivation). For each unit operation, generate data through small-scale studies like Design of Experiments (DoE) or one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) studies, varying critical process parameters (CPPs) and monitoring critical quality attributes (CQAs).

- Model Building: For each unit operation, build a multilinear regression model. The model should predict the output CQAs (e.g., HCP level, monomer purity) based on the input material attributes and the set-points of the CPPs.

- Model Concatenation: Link the unit operation models sequentially. The predicted output of one unit operation becomes the input for the subsequent unit operation's model.

- Monte Carlo Simulation: Run simulations on the integrated model. Incorporate random variability around process parameter set-points to reflect expected manufacturing variation. Run thousands of iterations to predict the distribution of the final drug substance CQAs.

- Derive Intermediate Acceptance Criteria (iACs): Using the simulation results, determine the range of CQA values at each intermediate process step that ensures the final drug substance will meet its specification limits with a sufficiently high probability (e.g., >99.73%). These ranges become the scientifically justified iACs.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this advanced methodology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Specification Studies

| Item | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) Production System | Serves as the candidate biologic product for process development and validation case studies [18]. |

| Host Cell Protein (HCP) ELISA Kit | An analytical procedure used to monitor the clearance of a host-related impurity, a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA), across downstream unit operations [18]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (UP-SEC) | An analytical procedure used to monitor product-related impurities (e.g., aggregates) and purity (e.g., monomer), which are CQAs [18]. |

| Chromatography Resins | Used in unit operations designed for the purification and clearance of impurities; their performance is modeled in the Integrated Process Model [18]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., JMP, Minitab) | Used for statistical analysis, including normality testing (Anderson-Darling), outlier detection (Grubb's test), calculation of tolerance intervals, and building regression models for the IPM [18] [23] [24]. |

The establishment of specifications in biopharmaceutical development is a critical activity that sits at the intersection of rigorous science and profound ethics. While statistical tools like tolerance intervals and process capability indices provide the technical backbone for setting acceptance criteria [23] [24], the underlying values and risk tolerances are shaped by broader bioethical frameworks. The ongoing dialogue between secular and religious bioethics, particularly through lenses like pluriversalism, challenges the field to create more inclusive and globally relevant moral infrastructures [5] [22]. For researchers and drug development professionals, recognizing this interplay is essential. It fosters a more holistic approach to process validation, where technical excellence is guided by a commitment to justice, stewardship, and the sacred dignity of human life, ultimately ensuring that medicines are not only effective and safe but also developed in an ethically sustainable manner.

Clinical ethics provides a structured approach to navigating complex moral dilemmas that arise at the crossroads of medical technology, human values, and life-and-death decisions. This comparative analysis examines ethical frameworks governing two critical domains: end-of-life care and organ transplantation. These domains represent particularly challenging arenas where advances in medical capabilities have created unprecedented ethical questions that blend philosophical foundations with practical clinical applications [25] [14]. The growing gap between organ supply and demand, coupled with an aging population facing prolonged end-of-life trajectories, has intensified the need for robust ethical frameworks that can guide practitioners, patients, and policymakers [26] [27].

Within bioethics, a fundamental tension exists between secular and religiously-grounded approaches to moral reasoning [14] [15]. Secular bioethics emerged in the late 20th century as a response to moral pluralism, seeking to develop "a set of principles and a method for moral decision-making acceptable to all, regardless of one's religion or ideology" [14]. Meanwhile, religious perspectives continue to shape ethical reasoning, with traditions such as Catholicism, Judaism, and Islam maintaining distinctive approaches to biomedical ethics while sharing common moral foundations with secular frameworks [15]. This analysis examines how these different foundational approaches manifest in concrete clinical contexts and governance models.

Comparative Ethical Frameworks: Secular and Religious Foundations

Philosophical Underpinnings and Key Principles

Table 1: Comparison of Secular and Religious Bioethical Foundations

| Aspect | Secular Bioethics | Religious Bioethics |

|---|---|---|

| Moral Source | Human reason, empirical evidence, and rational deliberation [14] | Divine revelation, sacred texts, and religious tradition [15] |

| Primary Principles | Autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice [26] | Dignity of the person, charity, stewardship, common good [15] |

| Approach to Suffering | Focus on prevention and relief through clinical intervention [14] | Potential meaning in suffering; spiritual response alongside physical care [14] |

| Decision-Making Process | Principlism, casuistry, consensus-based deliberation [27] | Authority of religious tradition, consultation with spiritual leaders [15] |

| Scope of Application | Universalist aspirations across diverse populations [14] | Particular to religious communities with potential for broader engagement [15] |

Secular bioethics is characterized by its systematic application of ethical principles that are theoretically accessible to all rational persons regardless of their metaphysical commitments. As one analysis notes, "Bioethics was born in a context characterized by moral pluralism and shifting ideas about the nature of moral authority; it was, and is, an effort to develop a set of principles and a method for moral decision-making acceptable to all, regardless of one's religion or ideology" [14]. This universalist aspiration, however, faces challenges in fully addressing existential questions of meaning that often arise in clinical contexts, particularly at the end of life [14].

Religious bioethics, while diverse across traditions, typically grounds moral reasoning in theological frameworks and understandings of human nature and purpose. The Catholic tradition, for instance, emphasizes that "the order of things must be subordinate to the order of persons, and not the other way around" [27], establishing a fundamental priority for human dignity over utilitarian calculations. While distinctive in their metaphysical foundations, religious perspectives often arrive at similar ethical positions as secular frameworks through different reasoning pathways, creating potential for collaboration in clinical settings [15].

Ethical Decision-Making Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the comparative decision-making processes in clinical ethics consultation, highlighting parallel pathways for secular and religious approaches:

Ethical Models in End-of-Life Care

Foundational Principles and Clinical Applications

End-of-life care presents distinctive ethical challenges as medical technology has transformed the dying process, creating complex decisions about limiting, withholding, or withdrawing treatments [26]. The universally recognized ethical principles guiding end-of-life care include autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice, with fidelity (truth-telling) representing an additional crucial principle [26]. These principles provide a framework for navigating specific clinical ethical challenges including resuscitation decisions, mechanical ventilation, artificial nutrition and hydration, terminal sedation, and requests for physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia where legally permitted [26].

Patient autonomy represents a cornerstone principle, implemented through advance care planning mechanisms including living wills, healthcare proxies, and "do not resuscitate" (DNR) orders [26]. These instruments allow patients to maintain control over medical decisions even after losing decision-making capacity. As one analysis notes, "Each patient's 'right to self-determination' requires informed consent in terms of medical intervention and treatment. A patient has both the 'right to demand the termination of treatment' (e.g., the discontinuation of life support) and the 'right to refuse treatment altogether'" [26]. However, this autonomy is not absolute and must be balanced against considerations of beneficence (promoting patient well-being) and nonmaleficence (avoiding harm) [26].

Comparative Institutional Approaches

Table 2: End-of-Life Care Models Across Clinical Settings

| Care Model | Ethical Priorities | Decision-Making Process | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital-Based Curative Care | Life extension, disease modification, technological intervention [26] | Physician-driven with patient consent; crisis-oriented decision-making [26] | Survival rates, physiological parameters, treatment success [26] |

| Palliative Care | Symptom relief, quality of life, holistic comfort [28] | Interdisciplinary team approach with patient and family engagement [28] | Pain scores, symptom burden, quality of life measures [28] |

| Hospice Care | Dignity in dying, comfort, family support [28] | Patient-centered goals; focuses on caring rather than curing [28] | Peaceful death, family satisfaction, bereavement outcomes [28] |