Research Misconduct Investigation Procedures: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the procedures, challenges, and best practices in research misconduct investigations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Research Misconduct Investigation Procedures: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the procedures, challenges, and best practices in research misconduct investigations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational definitions of fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, details the step-by-step institutional process from inquiry to investigation, and addresses complex challenges like protecting whistleblowers and managing confidential cases. Updated for 2025, it also explores the impact of new ORI rules, comparative institutional policies, and future directions for fostering research integrity in the biomedical field.

What Constitutes Research Misconduct? Understanding FFP and Evolving Definitions

Core Definitions and Regulatory Framework

Fabrication, Falsification, and Plagiarism (FFP) are universally recognized as the most serious forms of research misconduct, often termed the "cardinal sins" of research [1]. They fundamentally undermine the integrity of the research enterprise by eroding trust and corrupting the scientific record.

Official Definitions

According to the U.S. Office of Research Integrity (ORI), research misconduct is formally defined as fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results. It explicitly excludes honest error or differences of opinion [2].

The following table summarizes the core definitions of FFP:

| Term | Official Definition | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fabrication | Making up data or results and recording or reporting them [2]. | Inventing data for experiment runs that were never performed; creating a dataset from assumption rather than collection [3] [1]. |

| Falsification | Manipulating research materials, equipment, or processes, or changing or omitting data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record [2]. | Manipulating research instrumentation or images to distort the outcome; omitting conflicting data points to strengthen a correlation [2] [1]. |

| Plagiarism | The appropriation of another person's ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit [2]. | Using another's ideas or text without citation; representing reviewed, unpublished work as one's own [2] [1]. |

The Evolving Oversight Landscape

In the United States, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) Federal Policy established the foundational FFP definition in 2000 [4]. Oversight is continuously updated, with the ORI implementing a new Final Rule effective January 1, 2025, which clarifies key terms and procedures for handling allegations [3]. This framework retains FFP as the core of research misconduct, distinguishing it from other detrimental research practices.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Addressing FFP

FAQ: Common Scenarios and Solutions

Q1: A team member suggests "filling in" missing data points for a few experiment runs using estimated values to complete the dataset. Is this acceptable?

- A1: No, this is fabrication. Research claims must be based on a complete set of authentically collected data. Constructing or adding data that never occurred during the actual experiment is a serious breach of conduct [1]. All data, including outliers and null results, must be reported accurately.

Q2: During image analysis for a manuscript, a researcher adjusts the contrast of a blot to make a faint band more visible. Could this be considered misconduct?

- A2: It could be falsification if the manipulation misrepresents the original data. Any manipulation of images—including contrast, brightness, or cropping—that distorts the factual representation of the raw data or omits relevant information constitutes falsification [1]. All image processing must be explicitly disclosed and must not deceive the reader.

Q3: A researcher paraphrases several sentences from an unpublished grant proposal they reviewed, without citation, in their own grant application. Is this plagiarism?

- A3: Yes, this is plagiarism. Reviewing privileged information (e.g., grant proposals, journal manuscripts) carries an ethical obligation. The work of others cannot be used until it is publicly available and can be properly cited. Using this information constitutes plagiarism [1].

Q4: A researcher reuses lengthy passages from their own previously published paper in a new manuscript without quotation marks or citation. Is this considered plagiarism?

- A4: This is considered "self-plagiarism" or textual recycling. While the 2025 ORI Final Rule explicitly excludes self-plagiarism from the federal definition of research misconduct, it is still widely considered an unethical publication practice and may violate publisher policies or institutional standards [3]. It can also constitute duplicate publication, which misleads readers and publishers about the novelty of the work.

Investigation Protocol: The Institutional Response Workflow

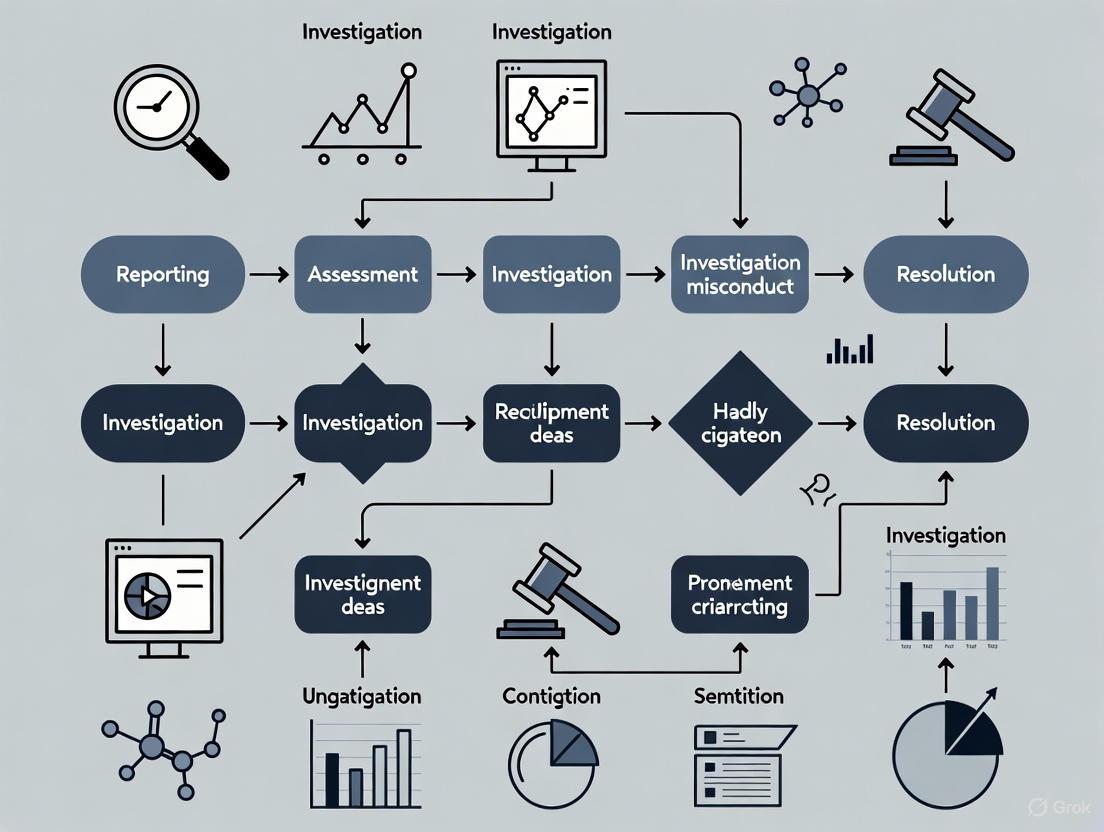

When an allegation of research misconduct is made, institutions follow a formal process defined by federal regulations. The diagram below outlines the key stages of this workflow.

Key Stages in Research Misconduct Investigation:

- Assessment & Inquiry: The institution conducts a preliminary review to determine if the allegation falls within the definition of research misconduct and if there is sufficient evidence to warrant a formal investigation [5].

- Investigation: If the inquiry recommends it, a formal investigation is launched to thoroughly examine the facts, collect evidence, and determine whether misconduct has occurred. The 2025 ORI Final Rule now allows institutions to add new respondents or allegations to an ongoing investigation without restarting the process, improving efficiency [3].

- ORI Notification & Reporting: Institutions are required to notify ORI when an investigation is warranted. If an investigation concludes with a finding of misconduct, a full report must be submitted to ORI [5].

- Adjudication & Actions: Based on the investigation report, the institution and ORI may impose administrative actions, which can include correction of the literature, supervision plans, and for the PHS, potential debarment from federal funding for a set period [5].

Preventing research misconduct requires a proactive approach centered on education, clear policies, and robust infrastructure [3]. The following table details key resources for maintaining a culture of integrity.

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function | Role in Preventing FFP |

|---|---|---|

| Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) Training | Provides education on ethical norms and regulatory requirements [5]. | Builds foundational knowledge of FFP, data management, and authorship, especially critical for trainees from diverse backgrounds [5]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) | Creates a secure, time-stamped, and immutable record of experimental data. | Provides a definitive record to combat allegations of fabrication and falsification; ensures data ownership and retention as required by funders [5]. |

| Plagiarism Detection Software | Scans textual content for similarity with published literature. | Helps researchers identify and correct improper citation before publication, preventing unintentional plagiarism. |

| Image Forensics Tools | Analyzes image files for signs of duplication or manipulation. | Aids in pre-publication verification and is used by journals and sleuths to detect image falsification [3]. |

| Data Management Plan (DMP) | A formal plan for collecting, storing, and sharing research data. | Promotes transparency and accountability, making data fabrication and falsification more difficult to conceal. |

In the rigorous world of scientific research, the integrity of the process is paramount. Allegations of research misconduct—defined by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) as fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism (FFP)—are serious and can have devastating career consequences [6]. However, not every error or scientific dispute constitutes misconduct. This guide provides essential technical support for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in distinguishing between true misconduct and the honest errors and differences of scientific opinion that are inherent to the research process [7]. Understanding this distinction is crucial for maintaining a healthy scientific environment where innovation and collegial debate can thrive without the chilling effect of unwarranted misconduct allegations [7].

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

What Constitutes Research Misconduct?

According to the PHS policies, a finding of research misconduct requires that three conditions are met, all proven by a preponderance of the evidence [6]:

- There is a significant departure from accepted practices of the relevant research community.

- The misconduct is committed intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly.

- The act falls within the definition of fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism.

The following table details the core elements of research misconduct.

Table 1: Core Elements of Research Misconduct

| Element | Official Definition | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fabrication | Making up data or results and recording or reporting them [8]. | Inventing data points for an experiment that was never performed; creating a dataset from imagination. |

| Falsification | Manipulating research materials, equipment, or processes, or changing or omitting data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record [8]. | Manipulating images (e.g., deleting/adding bands on a blot); systematically omitting outlier data without justification; changing results to fit a hypothesis. |

| Plagiarism | The appropriation of another person's ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit [8]. | Copying text from another publication without quotation marks or citation; republishing another scientist's work as one's own. |

What isNotMisconduct: Key Exclusions

The same regulatory frameworks that define misconduct also explicitly state what is excluded. Research misconduct does not include [6]:

- Honest Error(s): Inadvertent or unintentional mistakes made in the design, execution, analysis, or interpretation of research data.

- Difference(s) of Opinion: Disagreements or disputes over research methods, data analysis, interpretation of findings, or scientific judgment.

The critical element that separates misconduct from these exclusions is intent. Misconduct is marked by a deliberate intent to deceive, whereas honest error is unintentional [7]. A difference of opinion, meanwhile, is a legitimate scientific debate, often about the norms or their application, rather than a deliberate violation of them.

Troubleshooting Guide: Is It Misconduct or Not?

This guide addresses common scenarios to help you identify the source of a problem and determine the appropriate course of action.

Question: My colleague used an inappropriate statistical method that inadvertently strengthened their conclusions. Is this misconduct?

- Potential Issue: Honest Error vs. Falsification

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Identify the Norm: Determine the standard statistical practices in your specific field for this type of data and hypothesis.

- Assess Competence: Evaluate the researcher's statistical knowledge and training. Was the method choice a result of a knowledge gap?

- Check for Responsiveness: If the error was pointed out (e.g., by a reviewer or colleague), did the researcher correct it willingly and acknowledge the mistake?

- Likely Conclusion: If the most plausible explanation is a lack of knowledge or an unintentional oversight, and the researcher is corrective, this is honest error [7]. If the researcher has deep statistical knowledge and refuses to correct a known error that misrepresents the data, it may cross into deliberate falsification.

Question: A co-author accuses our lead investigator of misconduct for excluding data points she considered outliers. What should we do?

- Potential Issue: Difference of Opinion vs. Falsification

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reference Community Standards: Consult disciplinary norms for handling outliers. Are there established, objective criteria for exclusion?

- Document the Justification: Review the research records. Was the exclusion decision documented with a clear, scientific rationale?

- Pinpoint the Disagreement: Determine if the dispute is about the existence of a norm (is exclusion ever allowed?) or its application (was the norm correctly followed in this case?).

- Likely Conclusion: If the exclusion falls within a gray area of accepted practices and the disagreement is over scientific judgment, it is a difference of opinion [7]. If the data exclusion systematically and without justification alters the conclusions and violates clear norms, it could be falsification.

Question: I believe a senior researcher has plagiarized my grant application, which they reviewed. How can I be sure?

- Potential Issue: Plagiarism vs. Misuse of Privileged Information

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Compare the Texts: Perform a line-by-line comparison of your grant application and the researcher's subsequent work.

- Check for Attribution: Is your work copied without any citation or acknowledgment?

- Establish Privilege: Confirm that the researcher had access to your work through a confidential channel like grant review.

- Likely Conclusion: The unattributed copying of ideas, text, or data from a confidential document like a grant application is a serious form of plagiarism, often termed "theft of intellectual property" [9]. This is distinct from a authorship dispute and is a potential misconduct allegation.

Decision-Making Protocol for Allegations

When faced with a potential issue, follow a structured decision-making process. The flowchart below outlines the key questions to ask to distinguish between misconduct, honest error, and difference of opinion.

Regulatory Framework and Recent Updates

The U.S. Office of Research Integrity (ORI) has issued a revised Final Rule for the Public Health Service Policies on Research Misconduct (42 C.F.R. Part 93), with key dates that all researchers should know [10] [11].

Table 2: Key Dates for PHS Misconduct Policy Updates (2024 Final Rule)

| Deadline | Description | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| January 1, 2025 | Effective Date of the Final Rule [10]. | Use of the new rule is permitted but not yet mandatory. |

| January 1, 2026 | Applicable Date of the Final Rule [10] [11]. | All PHS-funded institutions must use the updated regulations for allegations received on or after this date. |

| April 30, 2026 | Annual Report Submission Due [10]. | Institutions must report all prior year research misconduct activity to ORI and assure their policies are compliant. |

A significant procedural update under the revised rules is that institutions now have greater flexibility to dismiss allegations on the basis of honest error or difference of opinion at an earlier assessment stage, rather than being required to proceed to a full investigation [11]. This change aims to reduce the burden on both institutions and respondents when an allegation is clearly not misconduct.

| Tool or Resource | Primary Function | Role in Preventing/Mitigating Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Digitally records research procedures and data with timestamps. | Provides an immutable record of work, helping to demonstrate actual practices and distinguish honest errors from fabrication/falsification. |

| Data Management Plan (DMP) | Outlines how data will be handled, stored, and shared throughout and after a project. | Ensures data integrity, traceability, and accessibility for review, mitigating disputes over data ownership and analysis. |

| Plagiarism Detection Software | Compares text against a vast database of published literature and the internet. | Helps researchers self-check manuscripts and proposals for unintentional plagiarism before submission. |

| Statistical Consultation Services | Provides expert guidance on experimental design and data analysis. | Helps prevent honest errors in methodology and analysis, strengthening study validity. |

| Institutional Research Integrity Officer (RIO) | The designated official responsible for overseeing the misconduct allegation process [9]. | A confidential resource for discussing concerns and understanding policies before making any formal allegation. |

FAQ on Distinguishing Misconduct

Q1: Can I be accused of misconduct for using a novel or controversial research method? No, the use of novel or unorthodox methods is not, in itself, misconduct. The National Academy of Sciences emphasizes that misconduct definitions should not discourage innovation [7]. An accusation in this context likely represents a difference of scientific opinion regarding the best methodological approach. The key is whether the method is applied and reported with transparency and without intent to deceive.

Q2: What is the difference between an honest error and reckless misconduct? An honest error is an inadvertent mistake, like a miscalculation due to a software flaw you were unaware of. Recklessness, as defined in the updated PHS regulations, involves acting with a heedless disregard for established norms, such as failing to perform basic data validation checks that are standard in your field, which could lead to a significant departure from accepted practices [6].

Q3: What should I do if I am unsure whether to report a potential misconduct? Always consult your institution's Research Integrity Officer (RIO). They are a confidential resource who can advise you on institutional policies, the nature of your concern, and potential steps forward without initiating a formal process [9]. This can help clarify if the issue is more appropriately resolved through collegial discussion.

Q4: How are disputes over authorship credit handled? Disputes over authorship or credit are explicitly excluded from the PHS definition of research misconduct (which covers plagiarism of ideas/text, not credit allocation) [6] [9]. These should be resolved using institutional policies, journal guidelines, and through dialogue among the collaborators.

The Office of Research Integrity (ORI) has issued its first major regulatory update since 2005, the Final Rule governing Public Health Service (PHS) Policies on Research Misconduct (42 C.F.R. Part 93) [12]. This modernization addresses technological advancements and policy developments that have transformed research over the past two decades. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these changes is crucial for maintaining compliance and upholding the highest standards of research integrity. The Final Rule, effective January 1, 2025, becomes applicable to all institutions on January 1, 2026, providing a critical preparation window [13] [12]. This technical support center outlines the key updates, with particular focus on the clarified definitions of self-plagiarism and recklessness, to equip you with the knowledge needed to navigate these revised procedures confidently.

Key Definitions: Understanding the Core Concepts

What Constitutes Research Misconduct?

Under the Final Rule, research misconduct remains defined by the core elements of fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism (FFP) in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results [3]. To establish misconduct, it must be proven that:

- There was a significant departure from accepted practices of the relevant research community.

- The act was committed intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly.

- The allegation is proven by a preponderance of the evidence [13] [14].

The Crucial Mental States: Intent, Knowledge, and Recklessness

The Final Rule introduces clarified definitions for the mental states required for a finding of research misconduct, which are vital for understanding the boundaries of acceptable conduct [14].

Table: Defined Mental States for Research Misconduct Findings

| Term | Definition in the Final Rule | Practical Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Intentionally | To act with the aim of carrying out the act [14]. | Requires demonstration of purposeful action to commit fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism. |

| Knowingly | To act with awareness of the act [14]. | Involves conscious awareness that one's actions constitute FFP, even without a specific aim to commit misconduct. |

| Recklessly | To act with indifference to a known risk of fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism [14] [15]. | Focuses on a conscious disregard for substantial and unjustifiable risks of FFP in the research process. |

The definition of recklessness is particularly nuanced, especially for senior researchers supervising projects. A finding of misconduct can be based on the theory that their supervision was reckless if it allowed falsified, fabricated, or plagiarized information to enter a publication, even if they did not perform the acts directly [15].

Self-Plagiarism: Excluded from the Federal Definition of Misconduct

One of the most significant clarifications in the Final Rule is the explicit exclusion of self-plagiarism from the federal definition of research misconduct [14] [16] [3]. The revised definition of plagiarism now expressly excludes:

- "The limited use of identical or nearly-identical phrases that describe a commonly-used methodology."

- Self-plagiarism.

- Authorship or credit disputes [16].

This regulatory change aligns with ORI's longstanding guidance. It is crucial to understand that while self-plagiarism is not considered federal research misconduct, it is still widely regarded as unethical publication behavior and may violate institutional policies or publisher standards [17] [3] [18]. The essence of the ethical violation is deception – passing off one's own previously disseminated work as new and original without informing the reader or publisher [19] [17].

Investigator's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Misconduct Proceeding Management

Effectively navigating research misconduct proceedings requires specific "reagent" solutions. The table below details essential components for managing this process under the new regulations.

Table: Essential Reagents for Managing Research Misconduct Proceedings

| Research Reagent Solution | Function & Purpose | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Interview Transcription Service | Creates verbatim records of all interviews conducted during the investigation stage [16]. | - Mandatory for investigation-stage interviews.- Transcripts must be provided to the respondent [16].- Not required for assessment or inquiry stages. |

| Sequestration System | Secures all research records and evidence needed for the proceeding [16]. | - Must occur before the respondent is notified or the inquiry begins.- Can use copies that are "substantially equivalent in evidentiary value" if originals are unavailable [16]. |

| Record Indexing Platform | Generates a detailed inventory of all sequestered evidence and the institutional record [14] [16]. | - Must list all records the institution relied upon.- Requires a general description of records not relied upon.- Critical for the final investigation report. |

| Confidentiality Management Protocol | Protects identities of respondents, complainants, and witnesses during the proceeding [13] [16]. | - Applies only until a final determination is made.- Permits disclosure to external entities (e.g., journals, collaborating institutions) with a "legitimate need to know" [13] [16]. |

| Multi-Institution Coordination Agreement | Establishes a lead institution and procedures for collaboration in cases involving multiple organizations [14] [16]. | - The lead institution is responsible for obtaining research records from others.- ORI plans to issue further guidance on this complex area. |

| Afoxolaner | Afoxolaner, CAS:1093861-60-9, MF:C26H17ClF9N3O3, MW:625.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ambazone | Ambazone, CAS:539-21-9, MF:C8H11N7S, MW:237.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Key Investigation Stages

The following workflows and methodologies are prescribed by the Final Rule for conducting research misconduct proceedings.

Protocol 1: The Assessment and Inquiry Workflow

The initial stages of a misconduct proceeding involve screening allegations and determining if a formal investigation is warranted. The Final Rule provides specific timeframes for these phases.

Methodology Details:

- Assessment: The institution must assess the allegation to determine if it is "sufficiently credible and specific so that potential evidence of research misconduct may be identified" [16]. The Final Rule removes the previously proposed requirement for a formal assessment report, requiring only that the outcome be documented [14] [16].

- Inquiry: If the assessment warrants it, the process moves to inquiry. The Final Rule clarifies that a committee is not required for the inquiry; it can be conducted by the Research Integrity Officer (RIO) or another designated official to streamline the process [16]. The inquiry must be completed within 90 days of initiation, with documentation required if this timeframe is exceeded [14].

Protocol 2: The Investigation and Adjudication Workflow

If the inquiry indicates the allegation "may have substance," the proceeding moves to the formal investigation stage, which involves a comprehensive evidence review.

Methodology Details:

- Investigation: A full review of all evidence is conducted, typically by a committee. The investigation must be completed within 180 days of initiation, with extensions requiring a written request to ORI [14].

- Interviews: A critical procedural requirement is that all interviews during the investigation must be transcribed, and these transcripts must be provided to the respondent [16].

- Report: The investigation report must include an inventory of sequestered evidence and a description of how sequestration was conducted [16].

- Appeal: The Final Rule removes the proposed 120-day time limit for institutional appeals, acknowledging this process is within the institution's purview. However, institutions must promptly notify ORI if an appeal is filed after the institutional record has been transmitted [14].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios: An FAQ Guide

Q1: Our investigation has uncovered evidence implicating a co-author not named in the original allegation. Can we add this person as a respondent? A: Yes. The Final Rule explicitly codifies the ability of institutions to add new respondents and allegations to an ongoing investigation. This allows for a more efficient and comprehensive review when patterns of misconduct surface, without needing to restart the entire process with a new inquiry for the additional respondent [16] [3].

Q2: We need to alert a journal about potential data integrity concerns in a published paper while our investigation is still ongoing. Does the confidentiality rule prohibit this? A: No. The Final Rule clarifies that confidentiality obligations regarding respondent identities apply only until a final determination is made. It explicitly permits disclosures to third parties with a "legitimate need to know," which includes "journal editors, publishers, co-authors, and collaborating institutions" [13] [16]. Furthermore, the rule states that institutions are not prohibited from managing published data or publicly acknowledging that data may be unreliable during an ongoing proceeding [13] [16].

Q3: A respondent has failed to provide their original lab notebooks, claiming they were lost. Can we draw an adverse inference from this? A: The Final Rule specifies that a respondent’s failure to retain records over time is not, on its own, evidence of misconduct [13]. However, an adverse inference can be drawn if the institution proves, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the respondent intentionally or knowingly destroyed the records after being informed of the allegations. If the respondent claims to possess the records but refuses to provide them, this failure can also be evidence of misconduct [13].

Q4: Is it ever acceptable to reuse my own previously published text in a new manuscript? A: This is a nuanced area. While self-plagiarism is not federal research misconduct, it is often considered an ethical violation in publishing. The key factor is transparency and deception. Reusing text describing standard methodologies may be acceptable, but reusing substantial portions of one's own prior work without citation misleads the reader and publisher by presenting old work as new [19] [17] [18]. You should always:

- Check the target journal's policy on text recycling.

- Cite your previous work comprehensively.

- When in doubt, seek permission from the publisher of the original work and the editor of the new journal.

Q5: How does the "subsequent use exception" work under the new rule? A: The six-year statute of limitations for research misconduct allegations can be extended if the respondent uses, republishes, or cites the portion of the research record alleged to be fabricated, falsified, or plagiarized within six years of the allegation being received [13] [14]. The Final Rule clarifies that this exception applies to use in "processed data, journal articles, funding proposals, data repositories, manuscripts, PHS grant applications, progress reports, posters, presentations, and other research records" [14]. Institutions must document their analysis if they determine the exception does not apply, but they no longer need to inform ORI before making this conclusion [13] [14].

Diagram: The Research Misconduct Proceeding Ecosystem

The following diagram maps the complete ecosystem of a research misconduct proceeding under the Final Rule, highlighting key actors, processes, and external interfaces.

FAQ: Which institutions are required to have a research misconduct policy?

Institutions that receive Public Health Service (PHS) funding for research activities must establish and maintain policies and procedures for addressing research misconduct allegations that comply with 42 C.F.R. Part 93 [14]. This includes:

- Universities and colleges

- Academic medical centers and medical schools

- Hospitals and healthcare systems

- Non-profit research institutions [14]

These institutions must file an assurance of compliance with the Office of Research Integrity (ORI), confirming they have written policies and procedures in place [10] [20].

FAQ: Who is considered a "respondent" or covered individual under these policies?

A "respondent" is the person against whom an allegation of research misconduct is directed. Policies cover any person who, at the time of the alleged misconduct, was:

- Employed by the institution

- An agent of the institution

- Affiliated with the institution [13]

This definition broadly includes principal investigators, co-investigators, trainees, students, and staff involved in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or reporting research results supported by PHS funds.

FAQ: What about collaborators or sub-awardees at other institutions?

For collaborations involving multiple institutions, the institutions must agree in writing on which one will take responsibility for conducting the research misconduct proceeding [21]. Sub-recipients of PHS funds (sub-awardees) are also directly responsible for complying with the regulations and must maintain their own active research integrity assurance with ORI [10] [13] [20].

FAQ: Does the policy only apply to currently funded research?

No. The policies apply to allegations of research misconduct involving:

- Research supported by PHS funds

- Applications for PHS support

- Research records related to PHS-supported research or applications [13]

This includes research that has concluded, as long as it was PHS-supported.

FAQ: Are there any time limits on when an allegation can be considered?

Yes, there is a general six-year statute of limitations from the date the institution receives the allegation [11]. However, a "subsequent use exception" may extend this period if the respondent uses, republishes, or cites the specific portion of the research record alleged to be fabricated, falsified, or plagiarized within the six-year window [13] [22] [21].

Key Requirements for Institutional Policies Table

The following table summarizes the core elements that institutional policies must address to comply with the 2024 Final Rule, effective January 1, 2026 [10] [11].

| Policy Requirement | Key Description | Regulatory Citation (42 C.F.R. Part 93) |

|---|---|---|

| Assurance of Compliance | Institution must have written policies and file an assurance with ORI [10]. | § 93.300-304 |

| Definitions | Must define misconduct as fabrication, falsification, plagiarism, committed intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly [22] [21]. | § 93.203, 213, 225-227 |

| Jurisdictional Scope | Applies to PHS-supported research, applications, and related records [13]. | § 93.102 |

| Procedural Stages | Must outline process for assessment, inquiry, and investigation [20] [21]. | § 93.307-310 |

| Confidentiality | Must protect identities of respondents, complainants, and witnesses, with disclosures permitted for those with a "need to know" [13] [22]. | § 93.106 |

| Recordkeeping | Must create, maintain, and provide ORI with a complete institutional record upon final determination [22] [21]. | § 93.317 |

Policy Coverage and Relationships Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the entities covered by institutional research misconduct policies and their relationships under PHS regulations.

Essential Compliance Components

The following table details key elements for maintaining an effective research misconduct compliance framework.

| Component | Function in Compliance Framework |

|---|---|

| Written Policies & Procedures | Foundation for handling allegations; required for ORI assurance [10] [11]. |

| Research Integrity Officer (RIO) | Primary institutional official responsible for overseeing misconduct proceedings [11] [21]. |

| Sequestered Research Records | Preserves evidence; policies must detail procedures for sequestration [21]. |

| Interview Transcripts | Creates verbatim record of interviews during investigation stage; must be provided to respondent [11] [22]. |

| Institutional Record | Comprehensive documentation of entire proceeding, provided to ORI after final determination [22] [21]. |

The Critical Role of the Research Integrity Officer (RIO)

FAQs: Understanding the RIO's Role and Procedures

What is a Research Integrity Officer (RIO)?

The Research Integrity Officer (RIO) is the institutional official responsible for overseeing the assessment, inquiry, investigation, and resolution of allegations of research misconduct [23]. They act as the central point of contact for all parties involved and ensure procedures comply with institutional policy and funding agency requirements, such as those from the Public Health Service (PHS) [24] [23].

When should I contact the RIO?

You should contact the RIO to report observed, suspected, or apparent misconduct in research, which includes fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results [23]. You may also contact the RIO for confidential consultations about concerns of possible research misconduct before making a formal report [23].

What are the stages of a research misconduct proceeding?

The process generally involves several key stages, as outlined in the table below [24] [23]:

| Proceeding Stage | Key Activities & Objectives |

|---|---|

| Allegation & Preliminary Assessment | RIO assesses the allegation to determine if it falls under the definition of research misconduct and if there is sufficient evidence to warrant an inquiry [23]. |

| Inquiry | A preliminary evaluation of evidence to determine if an investigation is warranted. Its purpose is not to reach a final conclusion about whether misconduct occurred [23]. |

| Investigation | A formal development and thorough examination of all relevant facts to determine if misconduct has occurred, and if so, who is responsible [24] [23]. |

| Institutional Decision & Reporting | The Provost or designated official reviews reports, makes a determination, and may impose sanctions. The RIO reports findings to sponsors as required [23] [25]. |

What are my rights and protections as a Complainant?

As a complainant, you have the right to:

- Be interviewed and present evidence during the inquiry [23].

- Testify before the investigation committee [23].

- Be informed of the results of the inquiry and investigation [23].

- Be protected from retaliation [23] [25].

You are responsible for making allegations in good faith, maintaining confidentiality, and cooperating with the inquiry or investigation [23].

What are my rights and protections as a Respondent?

As a respondent, you have the right to:

- Be informed of the allegations when an inquiry is opened [23].

- Be interviewed and present evidence during the inquiry and investigation [23].

- Review draft inquiry and investigation reports and submit comments [23].

- Be accompanied by legal counsel or a personal adviser at interviews or meetings [23].

You are responsible for participating in the process truthfully and in good faith, maintaining confidentiality, and not retaliating against any individual [23].

How does the RIO ensure confidentiality?

The RIO maintains the confidentiality of the proceedings to the extent possible without compromising public health and safety or the thoroughness of the investigation [23]. Disclosure of identities is limited to those who need to know [25]. However, anonymity for a complainant cannot be guaranteed if a case proceeds to a formal investigation and their testimony is required [23].

What is the RIO's role in managing evidence?

The RIO is responsible for the sequestration of research records. After initiating an inquiry, the RIO will promptly secure all relevant research records and materials, inventory the evidence, and store it securely [23] [25]. In modern cases, this can involve managing large volumes of digital data, which presents significant logistical and financial challenges [26].

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Materials for Research Integrity Processes

The following table details essential components for conducting a thorough and fair research misconduct proceeding.

| Item / Component | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Research Integrity Policy | Provides the formal framework and procedural rules for conducting inquiries and investigations into research misconduct allegations [23] [25]. |

| Secure Data Storage System | Preserves relevant research records and evidence (e.g., lab notebooks, digital data, emails) in a confidential and secure manner to ensure evidence integrity [23] [25]. |

| Conflict of Interest Checklist | A tool to ensure that individuals involved in the inquiry or investigation committee are unbiased and without unresolved personal, professional, or financial conflicts [25]. |

| Code of Practice for Research | A guiding document that supports researchers and organizations in upholding the highest standards of integrity, providing practical guidance for daily work [27]. |

| Interview Protocols | Standardized procedures for conducting interviews with complainants, respondents, and witnesses to ensure a consistent, objective, and thorough fact-finding process [23]. |

Research Misconduct Investigation Workflow

The diagram below outlines the general workflow for handling an allegation of research misconduct, from initial assessment to final institutional action.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Research Misconduct Proceedings

Challenge: A collaborative project across multiple institutions is facing an allegation. How is this handled?

- Diagnosis: Multi-institutional collaborations create questions of jurisdiction and parallel investigations [26] [25].

- Solution: Institutions should designate a single lead institution to conduct a joint research misconduct proceeding [25]. By mutual agreement, the investigation committee can include members from the collaborating institutions, and a joint determination can be made [25]. The RIO's role is to ensure collaboration without compromising the process, sharing information appropriately without creating exceptions that weaken standards [26].

Challenge: A complainant fears retaliation for reporting a concern.

- Diagnosis: Fear of retaliation is a significant barrier to reporting misconduct and creating a healthy research culture [27] [23].

- Solution: The RIO has a responsibility to protect complainants from retaliation [23]. Institutions must have a clear, enforceable non-retaliation policy [23] [25]. The RIO should be available to receive complaints regarding alleged retaliation and take appropriate action [23]. Building a culture of trust through transparency and consistent processes is a key preventive measure [26].

Challenge: The research data involved in the allegation is exceptionally large (e.g., terabytes).

- Diagnosis: Modern digital data storage makes the sequestration of research records a significant logistical and financial challenge [26].

- Solution: The RIO must partner with IT support to establish secure infrastructure for data storage and ongoing oversight [26]. This is a critical component of institutional support needed for the RIO to function effectively [26]. The RIO must take "all reasonable and practical steps" to obtain and sequester evidence, which may involve securing copies of data from shared instruments [25].

The Step-by-Step Investigation Process: From Allegation to Adjudication

Defining Research Misconduct and the Assessment Purpose

What is the official definition of research misconduct?

Research misconduct is formally defined as fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism (FFP) in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results [28] [29]. It does not include honest error or differences of opinion [28].

- Fabrication: Making up data or results and recording or reporting them [30] [29]

- Falsification: Manipulating research materials, equipment, or processes, or changing or omitting data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record [30] [29]

- Plagiarism: Appropriating another person's ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit [28] [30]

A finding of research misconduct requires that:

- There is a significant departure from accepted practices of the relevant research community [28] [6]

- The misconduct is committed intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly [28] [6]

- The allegation is proven by a preponderance of the evidence [28] [6]

What is the purpose of a preliminary assessment?

A preliminary assessment is the initial review of an allegation to determine whether it meets the definition of research misconduct and contains sufficient information to proceed with a formal inquiry [31] [23]. This initial screening ensures that matters outside the definition (such as authorship disputes or honest error) are identified early and not pursued through the full misconduct process [28] [29].

When does research misconduct fall under PHS jurisdiction?

For allegations to fall under Public Health Service (PHS) jurisdiction, they must meet three criteria [31]:

- The research in which the alleged misconduct took place must be supported by PHS funds or involve an application for PHS funds

- The alleged misconduct must meet the definition of research misconduct in 42 C.F.R. Part 93

- The allegation contains sufficient information to proceed with an inquiry

The Reporting Process: From Observation to Assessment

What are my responsibilities for reporting misconduct?

All individuals in the research community have a responsibility to report observed, suspected, or apparent research misconduct [28] [23]. If you are unsure whether a suspected incident falls within the definition, you may contact your Research Integrity Officer (RIO) to discuss the situation informally, which may include discussing it anonymously or hypothetically [28].

How do I make a report in good faith?

A good faith allegation means you have a belief in the truth of your allegation that a reasonable person in your position could have, based on the information known to you at the time [28] [5]. An allegation is not in good faith if made with knowing or reckless disregard for information that would disprove it [5]. Importantly, an allegation may be made in good faith even if an investigation subsequently does not support a finding of misconduct [5].

What protections exist for complainants?

Institutions must protect complainants from retaliation and make efforts to protect their privacy [28] [23]. Stanford University explicitly states that "reporting such concerns in good faith is a service to the University and to the larger academic community, and will not jeopardize anyone's employment" [29]. If you request anonymity, institutions will try to honor this request during the assessment phase, though anonymity may not be possible if your testimony is required in a subsequent investigation [23].

What information should a misconduct allegation include?

While procedures vary by institution, a comprehensive complaint should include [30]:

- Name and contact information of the person(s) involved in the alleged research misconduct

- How you became aware of the alleged research misconduct

- Names of any witnesses or others with pertinent information

- Description of the alleged research misconduct with date, time, location, and relevant facts

- Any relevant documents or evidence

- Any facts indicating imminent threat to safety of persons or property

The Preliminary Assessment Procedure

What happens after I submit a report?

The assessment process generally follows these steps:

Assessment and Initial Sequestration Workflow

What criteria does the RIO use during assessment?

The Research Integrity Officer (RIO) assesses whether the allegation [23] [32] [29]:

- Falls within the definition of research misconduct (fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism)

- Is sufficiently credible and specific so that potential evidence may be identified

- Involves PHS-supported research (if PHS jurisdiction is relevant)

What is sequestration and when does it occur?

Sequestration involves securing all original research records and materials relevant to the allegation [23] [32]. At Penn State, this occurs "prior to or at the time the Respondent is notified to preserve the data and protect the Respondent from concerns that they had the opportunity to tamper with evidence" [32]. The institution must take custody of research records and evidence, inventory them, and sequester them securely [30].

What are the possible outcomes of a preliminary assessment?

The assessment may conclude with one of these outcomes:

- Proceed to inquiry: The allegation meets criteria for research misconduct and has sufficient substance [29]

- No further action: The allegation does not meet the definition of research misconduct or lacks sufficient evidence [32]

- Referral to other offices: The matter may be better addressed through other institutional processes (e.g., authorship disputes, personnel issues) [28] [32]

Troubleshooting Common Assessment Scenarios

What if I'm unsure whether what I observed constitutes misconduct?

Solution: Contact your RIO for an informal consultation. You can discuss situations anonymously or hypothetically without making a formal allegation [28]. The RIO can help you determine whether the situation falls within the research misconduct definition before you decide whether to file a formal report.

What if the research isn't federally funded?

Solution: Institutions still typically address allegations involving non-federally funded research using similar procedures, though these cases "need not be reported to the federal government" [28]. The standard of proof and procedural fairness should be maintained regardless of funding source.

What if I need to report an imminent threat to public health or safety?

Solution: Immediately notify your RIO of any special circumstances, including when "health or safety of the public is at risk" or when "there is reasonable indication of possible violations of civil or criminal law" [30]. These situations may trigger exceptions to normal procedures and timelines.

What if I'm concerned about retaliation?

Solution: Document your concerns and report them to the RIO. Institutions explicitly prohibit retaliation against those who report concerns in good faith [23] [29]. The RIO is responsible for addressing allegations of retaliation and "protecting the positions and reputations of those persons who, in good faith, make allegations" [5].

What if the respondent leaves the institution during the assessment?

Solution: The process typically continues. Institutional policies often state they "may be applied to any individual no longer affiliated if the alleged misconduct occurred while the person was employed by, an agent of, or affiliated with the University" [28]. The RIO will coordinate with other institutions as needed.

Essential Research Integrity Tools

Table: Key Contacts and Resources for Research Misconduct Reporting

| Resource | Primary Function | Contact Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Research Integrity Officer (RIO) | Oversees misconduct proceedings; provides procedural guidance | First point of contact for any misconduct concerns |

| Institutional Legal Counsel | Provides legal advice on procedures and confidentiality | When complex legal issues arise |

| Department Chair/Dean | May receive initial reports; facilitates institutional process | Alternative reporting channel if RIO unavailable |

| Office of Research Integrity (ORI) | Provides federal oversight for PHS-funded research | When institutional process is incomplete or problematic |

Table: Documentation Requirements for Research Records

| Record Type | Retention Best Practice | Relevance to Misconduct Proceedings |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory notebooks | Maintain with dated entries; witness significant findings | Primary evidence for fabrication/falsification claims |

| Original data files | Store securely with metadata intact | Evidence of data manipulation or selective reporting |

| Email correspondence | Retain relevant research communications | Documentation of collaboration terms and data sharing |

| Manuscript drafts | Keep all versions with contributor comments | Evidence for plagiarism or authorship disputes |

| Protocol approvals | Maintain approved protocols and amendments | Baseline for assessing protocol deviations |

Regulatory Framework and Institutional Variations

Are there time limitations for reporting misconduct?

Yes, the PHS regulations apply only to research misconduct occurring within six years of the date an institution or HHS receives an allegation, with several exceptions [28] [6]:

- Subsequent use exception: The respondent continues or renews the alleged misconduct through citation or republication

- Health or safety exception: The alleged misconduct would possibly have a substantial adverse effect on public health or safety

How do institutional policies relate to PHS standards?

Institutions must meet PHS regulatory requirements for federally-funded research, but they may have additional or broader standards for other matters [5]. As noted by ORI, "an institution may find conduct to be actionable under its own standards, even though the action does not meet the PHS definition of research misconduct" [5].

What are the confidentiality requirements during assessment?

Confidentiality is maintained by limiting disclosure of identities "to those who need to know in order to carry out a thorough, competent, objective, and fair research misconduct proceeding" [28] [6]. However, institutions must disclose identities to ORI when required, and confidentiality limitations no longer apply once an institution makes a final determination of research misconduct [6].

In research misconduct investigation procedures, the prompt and proper sequestration of physical evidence is a foundational step for ensuring evidence integrity [33]. If evidence is not sequestered systematically and promptly with an identifiable chain of custody, its integrity can be questioned, creating avoidable complications in misconduct cases [33]. This guide provides detailed protocols and troubleshooting advice for researchers and administrators involved in this critical process.

Step-by-Step Sequestration Protocol

Preparation and Notification

- Understand Authorities: Know the policies granting authority to sequester data. Under PHS grant policy, for example, data generated under a grant belong to the grantee institution, not the principal investigator [33].

- Formal Notification: Prepare and deliver formal notification to the respondent (the person against whom the allegation is directed). This notification should identify the authorities, nature of the allegations, process to be followed, and the respondent's rights [33] [28].

Executing the Sequestration

- Timing: Data sequestration should occur concurrent with notifying the respondent [33] [34].

- Assemble a Team: The sequestration team may include an authorized institutional official (often a Research Integrity Officer), the respondent’s supervisor, an expert who understands the research, an IT specialist, legal counsel, and security personnel as needed [33] [34].

- Secure Evidence: Confidentially arrange access to data and related evidence. The focus is on circumstances that protect evidence integrity while allowing discreet, confidential, timely, and efficient sequestration [33] [34]. Prior to identifying physical evidence, take measures to retain unaltered electronic files (e.g., Google Vault hold) [34].

Identifying and Inventorying Evidence

Evidence is anything that tends to prove or disprove an alleged fact and includes [34]:

- Lab records and notebooks (physical and electronic)

- Research data (e.g., micrographs)

- Collateral information (e.g., centrifuge logs, order forms, telephone notes)

- Computer files (hard drives, email, instrument-connected computers)

- Grants, progress reports, manuscripts (drafts and published), abstracts, theses, presentations

- Correspondence with editors and others

Inventory Process: Compile an inventory of all sequestered research records and evidence [34]. For notebooks and folders, count the number of pages and ensure each has a unique identifier [33]. The authorizing official should sign each receipt, and the respondent should be requested to countersign. The respondent should receive copies of the receipt forms [33].

Maintaining Chain of Custody and Storage

- Chain of Custody: Maintain an identifiable chain of custody by inventorying physical evidence, providing receipts, logging supervised access, and documenting when evidence is released and to whom [33] [34].

- Secure Storage: All evidence must be stored as part of the institutional record in a secure location in accordance with institutional and federal policies (e.g., for seven years after an investigation) [34].

- Access to Records: The respondent must be assured supervised access to the original research records or copies of records necessary to continue research during sequestration [33] [34].

Troubleshooting Common Sequestration Issues

Q1: What if the respondent is uncooperative and refuses to identify all potential evidence?

- Solution: Emphasize that evidence offered later in the process may be given less weight [33]. The Research Integrity Officer (RIO) has the authority to remove data and evidence related to the inquiry to fulfill obligations under federal regulations and university policy [34]. Institutional officials, including respondents, have an obligation to provide evidence relevant to research misconduct allegations [28].

Q2: How should we handle electronic data on shared instruments or complex digital formats?

- Solution: For scientific instruments shared by multiple users, custody may be limited to copies of the data or evidence, provided those copies are substantially equivalent to the evidentiary value of the instruments [30]. Involve an IT expert early to retain copies of unaltered electronic files and ensure proper handling of complex digital data [34].

Q3: What steps ensure the integrity of sequestered evidence is not questioned later?

- Solution: The core of evidence integrity lies in a systematic process and a clear chain of custody [33]. Key steps include:

- Prompt Sequestration: Secure evidence immediately upon notification [33].

- Detailed Inventory: Meticulously log all items, including page counts and unique identifiers [33] [34].

- Documented Chain of Custody: Use custody forms, labels, and receipts signed by both the official and the respondent [33] [34].

- Secure, Access-Logged Storage: Store originals securely and log all supervised access [34].

Q4: The allegation involves PHS-funded research. Are there special requirements?

- Solution: Yes. If the inquiry determines an investigation is warranted, the institution must provide ORI with the written finding and a copy of the inquiry report within 30 days [30]. The institution must also notify ORI of special circumstances, such as threats to public health or reasonable indication of criminal violations [30]. The institution must transfer custody or provide copies of the institutional record and any sequestered evidence to HHS upon request [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What constitutes research misconduct? A: Research misconduct is typically defined as fabrication (making up data or results), falsification (manipulating research materials, processes, or data), or plagiarism (appropriating another's ideas or words without credit) in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results. It does not include honest error or differences of opinion [30] [28].

Q: What is the difference between an inquiry and an investigation? A: An inquiry is a preliminary information-gathering and fact-finding step to determine if an allegation warrants a formal investigation [30] [28]. An investigation is the formal development of a factual record and examination of that record to determine if research misconduct occurred [28].

Q: How long does an inquiry take? A: Institutions often aim to complete an inquiry within 60 calendar days of initiation, though circumstances may warrant a longer period. If the inquiry takes longer, the reasons should be documented [30].

Q: What are the rights of a respondent in a misconduct proceeding? A: Key rights include being notified of the allegations, having the opportunity to comment on the inquiry report, being given a copy of the institution's research misconduct policy, and having supervised access to sequestered research records or copies to continue their work [33] [30] [34].

Q: What happens if research records are destroyed or absent? A: The destruction or absence of research records can itself be evidence of misconduct if the institution establishes that the respondent intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly had the records and destroyed them, or failed to maintain or produce them, and that this conduct is a significant departure from accepted research practices [28].

Essential Documentation and Tools

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Evidence Management

| Item or Document | Primary Function in Sequestration |

|---|---|

| Custody Forms & Receipts | Establishes a documented chain of custody; signed by official and respondent [33]. |

| Evidence Labels & Markers | Clearly identifies and tracks all sequestered items [33] [34]. |

| Secure Storage Containers | Protects physical evidence from tampering or damage [33]. |

| Digital Evidence Preservation Tools (e.g., Google Vault) | Retains unaltered electronic files and emails [34]. |

| Inventory Log | A comprehensive list of all sequestered materials, describing the sequestration process [34]. |

| Procedural Aspect | Requirement or Standard | Governing Policy / Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Inquiry Completion | Within 60 days (unless circumstances warrant longer) [30]. | AACP Procedures [30] |

| Investigation Notification | Begin within 30 days after determining an investigation is warranted [30]. | AACP Procedures [30] |

| Record Retention | At least 7 years after the termination of the inquiry or investigation [30] [34]. | AACP, University of Minnesota [30] [34] |

| Standard of Proof | Preponderance of the evidence [30] [28]. | AACP, Harvard FAS [30] [28] |

Experimental Workflow: Research Evidence Sequestration

Definition and Purpose of an Inquiry

An inquiry is the critical first step in the research misconduct process, serving as a preliminary evaluation to determine if a full investigation is warranted. Its purpose is not to reach a final conclusion about whether misconduct definitively occurred or to assign responsibility [35] [23]. Instead, the inquiry functions as an initial screening to separate allegations that deserve further investigation from those that are unjustified or mistaken [36]. It involves a preliminary evaluation of the available evidence and testimony from the respondent, the complainant (whistleblower), and key witnesses [35].

The Inquiry Process: A Step-by-Step Guide

The inquiry phase follows a structured sequence to ensure a fair and thorough preliminary review. The flowchart below illustrates the key stages an allegation passes through during this process.

The specific procedures at each stage are detailed below:

- Initiation and Notification: The process begins after an initial assessment determines the allegation is sufficiently credible, specific, and falls within the definition of research misconduct [36] [23]. The Research Integrity Officer (RIO) must then notify the respondent (the person against whom the allegation is made) in writing of the allegations [36]. This notification should clearly identify the original allegation and any related issues [23].

- Sequestration of Research Records: Upon or before initiating the inquiry, the institution must take all reasonable and practical steps to obtain custody of all research records and evidence needed to conduct the proceeding [30]. This sequestration involves securing data both physically (e.g., copying a hard drive) and remotely (e.g., data from cloud backups) to preserve evidence and protect the respondent from concerns of evidence tampering [32]. An inventory of sequestered materials is required [37].

- Preliminary Scientific Review: The core of the inquiry is a preliminary review of the evidence. This is typically performed by a subject matter expert or an inquiry committee [32] [36]. The review involves interviewing the complainant, respondent, and key witnesses, as well as examining relevant research records [23]. The committee members must be impartial and have no unresolved personal, professional, or financial conflicts of interest [36].

- Inquiry Report and Comment Period: A written inquiry report is prepared, documenting the findings [35] [36]. The RIO provides the respondent and complainant with a draft of this report for comment, typically allowing a 10-day period for feedback [36]. Any comments submitted are attached to the final report [36].

- Decision by Deciding Official (DO): The final inquiry report is sent to a Deciding Official (DO), such as a Provost or Designated Research Official [32] [36]. The DO consults with the RIO and makes a written determination on whether an investigation is warranted [36]. All parties, including the complainant, respondent, and relevant institutional leadership, are notified of this outcome [32].

Quantitative Data: Timelines and Committee Composition

Adhering to established timelines and committee composition is essential for a rigorous and fair inquiry process. The tables below summarize these key quantitative metrics.

Table 1: Inquiry Phase Timelines and Deadlines

| Action | Standard Timeline | Governing Policy / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Assessment | Preferably within 1 week [36] | University of Wisconsin-Madison |

| Complete Inquiry | 60 days from initiation [36] [30] | PHS Regulation 42 CFR § 93 [37] |

| Respondent Comment on Draft Report | 10 calendar days [36] | University of Wisconsin-Madison & Penn State |

| DO Decision after Final Report | Within 20 days of receipt [36] | University of Wisconsin-Madison |

| Begin Investigation (if warranted) | Within 30 days of inquiry decision [36] | University of Wisconsin-Madison |

Table 2: Inquiry Committee Composition and Standards of Proof

| Element | Requirement | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Committee Size | At least 3 members [36] | |

| Committee Expertise | Scientific competence appropriate for the case, without conflicts of interest [36] | Members can be from inside or outside the institution [36] |

| Standard for Investigation | Allegation may have substance [30] | "Reasonable basis" that allegation falls within definition of research misconduct [30] |

| Burden of Proof for Final Misconduct Finding | Preponderance of the evidence [30] | PHS Policies (Also required for proving intentional destruction of records) [13] |

Determining if an Investigation is Warranted

The Deciding Official's determination to proceed to an investigation hinges on two key criteria [30]:

- There is a reasonable basis for concluding that the allegation falls within the definition of research misconduct (fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism) [30].

- The preliminary information-gathering from the inquiry indicates that the allegation may have substance [30].

An investigation is not warranted if the inquiry determines that the allegation does not meet the definition of research misconduct or lacks substantive evidence [36]. In such cases, the DO may still direct the RIO to pursue corrective actions, such as re-training in laboratory practices, even without a formal investigation [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following tools and resources are critical for effectively managing and participating in a research misconduct inquiry.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for the Inquiry Process

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Institutional Policy & Procedures (e.g., RP02, Faculty Policy II-314) | Provides the definitive rulebook for the entire misconduct process, outlining specific institutional steps, rights, and responsibilities [32] [36]. |

| PHS Policies on Research Misconduct (42 CFR Part 93) | The federal regulation governing inquiries and investigations for Public Health Service-funded research, effective in updated form on Jan 1, 2026 [37] [12]. |

| Secure Data Storage & Chain-of-Custody Log | A system (digital and/or physical) for sequestering and inventorying all relevant research records and evidence, crucial for preserving integrity [32] [37]. |

| Confidentiality Agreement Templates | Legal documents to protect the privacy of respondents, complainants, and witnesses by limiting disclosure of information to those who need to know [32] [36]. |

| ORI Sample Policies and Procedures | A non-binding but authoritative template from the Office of Research Integrity to help institutions build compliant frameworks for handling allegations [38] [37]. |

| AZD7254 | `AZD7254 Research Compound|RUO` |

| Fatostatin | Fatostatin, CAS:125256-00-0, MF:C18H18N2S, MW:294.4 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between an inquiry and an investigation? An inquiry is a preliminary fact-finding step to determine if an allegation has enough substance to justify a formal investigation. An investigation is a formal, comprehensive development of the factual record to determine whether misconduct occurred, by whom, and to what extent [35] [36].

What are my rights as a respondent in an inquiry? You have the right to be notified of the allegations in writing, to be interviewed and present evidence during the inquiry, to review and comment on the draft inquiry report, and to be protected from retaliation. You may also consult with legal counsel or a personal adviser at your own expense [23].

What constitutes "sufficient evidence" to move to an investigation? The threshold is not "proof" of misconduct. Instead, an investigation is warranted if there is a reasonable basis to believe the allegation falls within the definition of research misconduct (FFP) and the preliminary information suggests the allegation has merit [30].

How is confidentiality maintained during an inquiry? The identities of respondents and complainants are disclosed only to those with a legitimate need to know to carry out the proceeding [32] [13]. The institution must also protect the identity of research subjects [30]. However, confidentiality is not absolute, and identities may be disclosed to journals, collaborating institutions, or ORI as necessary [13] [30].

Investigation Workflow and Timelines

What is the standard workflow and timeline for a formal investigation?

A formal research misconduct investigation is a multi-stage process defined by strict procedural and documentation requirements. The following diagram illustrates the key phases from allegation to final report.

Key Investigation Phase Timelines

| Phase | Purpose | Maximum Timeline | Key Changes in 2024 Final Rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Evaluate allegation credibility, jurisdiction, and whether it meets research misconduct definition [21] [37] | Not specified | Formalized as mandatory first phase [21] |

| Inquiry | Determine if allegation merits formal investigation [37] | 90 days [37] | Inquiry committee now optional; RIO or designated official may conduct [21] |

| Investigation | Formal examination to develop factual record, make misconduct determination [37] | 180 days [21] [37] | Extended from 120 days; more realistic for complex cases [21] [11] |

Evidence Handling and Sequestration

How should evidence be secured and documented during an investigation?

Proper evidence sequestration is critical for preserving integrity. The process must begin immediately upon receiving a credible allegation [37].

Evidence Sequestration Protocol

| Step | Action | Documentation Required |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Immediate Seizure | Secure all original research records, data, and materials relevant to allegation [37] | Inventory with dates, descriptions, and sequestering official [21] [37] |

| 2. Chain of Custody | Maintain strict control and documentation of all access to sequestered materials [37] | Log of all individuals accessing evidence with dates and purposes [37] |

| 3. Substantially Equivalent Copies | Use certified copies if original records cannot be obtained [21] | Documentation explaining why originals unavailable and equivalence verification [21] |

| 4. Interim Sequestration | Secure new records as they become known during investigation [21] | Supplemental inventory documenting additional materials [21] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Evidence Issues

Issue: Respondent claims records are unavailable or lost.

- Solution: Document the claim. Note that failure to retain records alone is not evidence of misconduct, but intentional destruction after allegation notification can be [13].

Issue: Evidence exists in multiple locations or institutions.

- Solution: Coordinate sequestration with all involved institutions. The Final Rule provides guidelines for multi-institutional proceedings [21].

Issue: Digital evidence requires specialized handling.

- Solution: Engage IT/forensic specialists early to preserve metadata and maintain evidentiary value.

Interview Procedures and Transcripts

What are the requirements for conducting and documenting interviews?

Interview protocols have been significantly enhanced under the new regulations, with specific transcription requirements.

Investigation Interview Requirements

| Requirement | Application | Documentation Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Mandatory Transcription | All interviews conducted during investigation phase [21] [11] | Word-for-word transcripts; audio recording alone insufficient [21] [11] |

| Respondent Access | Respondent must receive copies of all interview transcripts [21] [11] | Transcripts may be redacted to maintain witness confidentiality [11] |

| Exhibit Numbering | Materials shown to interviewees must be numbered as exhibits [21] | Exhibits referenced by number during interview and included in institutional record [21] |

| Investigation vs. Inquiry | Inquiry phase interviews should be transcribed but not required [21] | Inquiry interviews may be documented with summaries or recordings [21] |

FAQ: Interview Process

Q: Can witnesses remain anonymous?

Q: What if a witness refuses to be interviewed?

- A: Document the refusal. Proceed with available evidence and note the absence of testimony in the final report.

Q: How should we handle reluctant internal witnesses fearing retaliation?

Documentation and Reporting Standards

What documentation must be included in the final investigation report?

The institutional record must provide a complete account of the investigation for ORI review [21] [37].

Investigation Report Requirements

| Component | Description | Regulatory Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Committee Composition | Names and qualifications of investigation committee members [21] | §93.310(c) - Appropriate scientific expertise [11] |

| Evidence Inventory | Complete inventory of sequestered research records and description of sequestration process [21] | §93.310(f) - Required component [21] |

| Interview Transcripts | Transcripts of all interviews conducted during investigation [21] [11] | §93.310(g) - Mandatory inclusion [21] |

| Identification of Publications | List all publications, manuscripts, and grant applications containing allegedly falsified data [21] | §93.310(i) - Specific identification required [21] |

| Scientific Analyses | Description of any scientific or forensic analyses conducted [21] | §93.310(j) - Analytical methods documentation [21] |

| Procedural History | Timeline of investigation and key procedural milestones [21] | §93.310(h) - Required component [21] |

Complete Institutional Record for ORI Submission

After final determination, institutions must transmit the full institutional record to ORI, including [21]:

- All records compiled or generated and relied upon in proceedings

- Documentation of assessment stage

- Inquiry report (if inquiry conducted)

- Transcripts of all transcribed interviews

- Record of any institutional appeal

- Index of all research records and evidence compiled

- General description of records sequestered but not relied upon

Research Reagent Solutions for Investigation Support

Essential Research Integrity Tools

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Investigations |

|---|---|---|

| Image Analysis | Image duplication detectors, forensic analysis tools [3] | Identify potential image manipulation in publications |

| Text Similarity | Plagiarism detection software, text-matching algorithms [3] | Detect potential plagiarism across research literature |

| Data Management | Electronic Research Administration (eRA) systems [3] | Track compliance, manage protocols, document training |

| Record Keeping | Secure digital repositories with chain-of-custody features [37] | Maintain sequestration integrity and access logs |

| Reference Validation | Citation analysis tools, bibliography auditors | Verify reference accuracy and identify citation manipulation |

Procedural Complexities and Solutions

How should investigators handle challenging procedural situations?

Addressing Common Investigation Challenges

| Challenge | Regulatory Context | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Respondents | Adding new respondents to ongoing proceeding [21] | No requirement for new inquiry; may add respondents to existing investigation with proper documentation [21] |

| "Subsequent Use" Exception | Narrowed exception applying only to specific portions of research record [13] [21] | Carefully document which "portion(s)" were used, republished, or cited within 6 years of allegation [13] [11] |