Legally Authorized Representative Informed Consent: A Comprehensive Guide for Ethical Research with Vulnerable Populations

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for the legally authorized representative (LAR) informed consent process.

Legally Authorized Representative Informed Consent: A Comprehensive Guide for Ethical Research with Vulnerable Populations

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for the legally authorized representative (LAR) informed consent process. It covers the foundational ethical and legal principles derived from the Nuremberg Code and federal regulations, outlines practical methodological steps for implementation, addresses common challenges with vulnerable populations, and explores validation techniques to ensure comprehension and regulatory compliance. The article also discusses the implications of the 2025 FDAAA 801 Final Rule, which mandates the public posting of informed consent documents, emphasizing the growing importance of transparent, participant-centered consent processes.

The Bedrock of Ethical Research: Understanding LAR Consent and Its Legal Framework

In clinical research, the principle of informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical practice. However, a significant challenge arises when prospective adult participants lack the decision-making capacity to provide this consent due to cognitive impairment or other conditions. In these circumstances, the role of the legally authorized representative (LAR) becomes critical. An LAR is an individual or entity authorized under applicable law to consent on behalf of a prospective subject to their participation in research [1] [2]. This application note defines the LAR within the context of clinical research, delineating who qualifies for this role, the specific circumstances mandating their involvement, and the associated regulatory and ethical obligations for researchers. Establishing robust protocols for LAR consent is essential for the ethical inclusion of vulnerable populations in research, thereby advancing both scientific knowledge and patient care.

Defining the Legally Authorized Representative

Core Concept and Regulatory Basis

A Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) is an individual or judicial body empowered by law to provide informed consent for research participation on behalf of another adult who lacks the capacity to do so [1] [2]. This concept is distinct from a parent or guardian providing permission for a child to participate in research, as it pertains specifically to adults who have lost, either temporarily or permanently, the ability to make informed decisions [2].

The regulatory foundation for LARs is established in the Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46.102(c) and 21 CFR 50.3(l)), which define an LAR as an entity "authorized under applicable law to consent on behalf of a prospective subject" [1]. It is crucial to recognize that all adults are presumed competent to consent unless they have been legally adjudicated as incompetent [1]. Therefore, the use of an LAR is not based merely on a diagnosis but on a formal determination of impaired capacity.

Distinguishing LARs from Other Roles in the Consent Process

The consent process may involve several parties, and it is important to differentiate the LAR from other roles:

- LAR vs. Parent/Guardian for Minors: A parent or guardian provides permission for a child (a minor) to participate in research. An LAR, in contrast, provides consent for an adult who lacks capacity [2].

- LAR vs. Witness: A witness is an impartial observer of the consent process, often required when a participant cannot read or has a physical impediment to signing. The witness attests to the integrity of the consent process but does not make the decision for the participant [2].

- LAR vs. Healthcare Agent/Proxy: A healthcare agent, appointed through a healthcare proxy document, is a specific type of LAR. The proxy is a legally recognized document that allows a principal to designate an agent to make healthcare decisions, including research participation, upon the principal's loss of capacity [3]. Not all LARs are appointed via a proxy; many are designated by state statute based on their relationship to the patient.

Circumstances Requiring LAR Involvement

LARs are required in specific, legally-defined situations involving adults with compromised decision-making capacity. The table below summarizes the primary circumstances and the governing principles.

Table 1: Circumstances Requiring Legally Authorized Representative Consent

| Circumstance | Description | Governing Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Impairment | Adults with conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, dementia, severe mental illness, or developmental disabilities that impair their ability to understand research and provide reasoned consent [1]. | Protection of a vulnerable population; the mental disability may compromise capacity for reasoned decision-making [1]. |

| Prospective Incapacity | For research involving subjects with progressive or fluctuating conditions (e.g., some organic brain diseases), where capacity may be lost during the study [1]. | Requires ongoing communication with the LAR and periodic re-assessment of the subject's capacity [1]. |

| Medical Emergency | In life-threatening situations where the subject is incapacitated, an LAR may be consulted for consent if it is impracticable to obtain consent from the subject and the research allows for such an exception [4]. | Justified when research has potential clinical relevance and obtaining direct consent is not feasible [4]. |

| Physical Incapacity | Rare cases where a subject has the mental capacity to consent but has a physical impediment that prevents them from documenting consent (e.g., complete paralysis). In such cases, a witness process is typically used, but an LAR may be involved if the physical condition is paired with cognitive issues [2]. | Focus on the ability to communicate a decision, not just the physical act of signing. |

It is important to note that LARs are generally not permitted to consent to certain high-sensitivity research categories. In Virginia, for example, an LAR cannot provide consent for non-therapeutic research that presents more than a minor increase over minimal risk, nor for procedures involving non-therapeutic sterilization, abortion, or psychosurgery [1]. Furthermore, any expressed objection from the prospective subject overrides the LAR's consent [1].

Qualification and Hierarchy of LARs

The qualifications for who may serve as an LAR are typically defined by state law, and the hierarchy can vary by jurisdiction. Researchers must be familiar with the laws of the state in which the research is conducted [1].

Table 2: Example Hierarchy of Legally Authorized Representatives for an Incapacitated Adult (Based on Virginia Law)

| Order of Priority | Legally Authorized Representative | Notes and Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agent under an Advance Directive | The individual appointed by the subject in a healthcare proxy or advance directive, provided the document explicitly authorizes decisions regarding research participation [1] [3]. |

| 2 | Legal Guardian | A court-appointed guardian with authority to make healthcare decisions. |

| 3 | Spouse | Excludes cases where divorce proceedings have been filed and the decree is not yet final [1]. |

| 4 | Adult Child | |

| 5 | Parent | For an adult subject. |

| 6 | Adult Sibling | |

| 7 | Any other person/judicial body authorized by law | Serves as a catch-all for other specific situations defined by state statute [1]. |

Key considerations for LAR qualification:

- Conflict of Interest: Typically, the operator, administrator, or employee of a hospital may not act as an agent unless they are related to the principal. Similarly, a physician who is the subject's attending physician cannot also serve as their healthcare agent [3].

- Multiple LARs: If two or more persons with equal decision-making priority disagree about the subject's participation, the subject should not be enrolled in the research [1].

- Authority Commencement: The authority of a healthcare agent (a type of LAR) commences only after a physician or nurse practitioner makes a formal determination that the principal lacks decision-making capacity. This authority ceases if the principal regains capacity or revokes the proxy [3].

Protocols for LAR Consent and Subject Assent

Implementing a valid consent process involving an LAR requires a structured protocol to ensure ethical and regulatory compliance.

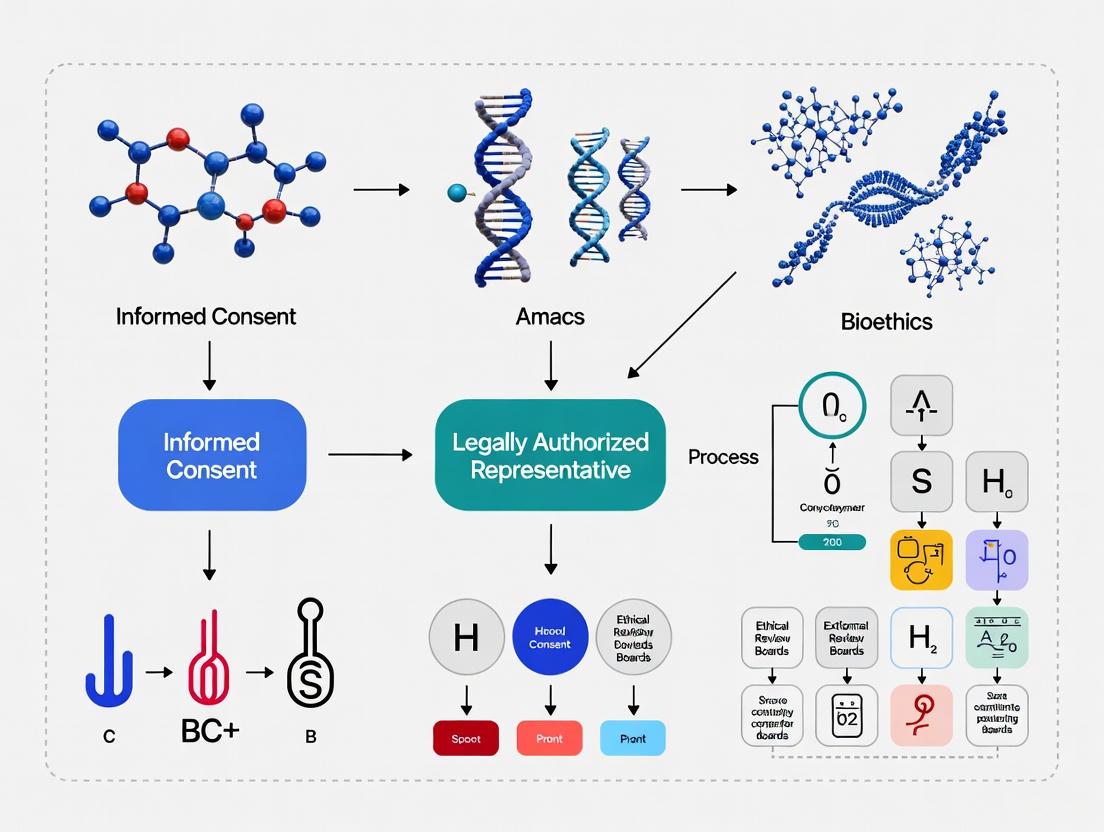

Protocol Workflow: LAR Identification and Consent Process

The following diagram visualizes the key stages of engaging a Legally Authorized Representative in the informed consent process.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Protocol Stages

1. Assessment of Decision-Making Capacity

- Purpose: To determine if a potential subject possesses the capacity to provide independent informed consent.

- Procedure: The Principal Investigator (or qualified designee) must conduct a direct assessment. The protocol submitted to the IRB must detail a specific plan for this assessment [1].

- Method: While no single standardized measure is mandated, the assessment should evaluate the subject's ability to:

- Understand the nature of the research and information relevant to participation.

- Appreciate the consequences of participation for their own situation.

- Understand the alternatives to participation.

- Reach a reasoned decision [1].

- Documentation: The assessment process and its outcome must be documented in the research record. The level of capacity required is proportional to the risks of the protocol.

2. Formal Determination of Incapacity

- Purpose: To legally trigger the authority of the LAR.

- Procedure: For a healthcare proxy to become active, a determination must be made by the subject's attending physician or attending nurse practitioner [3].

- Method: The determination must be in writing and include the clinician's opinion on the cause, nature, extent, and probable duration of the incapacity [3].

- Notification: Notice of this determination must be given to the subject (if able to understand) and to the identified LAR [3].

3. LAR Identification and Consent Discussion

- Purpose: To ensure the correct individual provides surrogate consent.

- Procedure: Consult the applicable state law hierarchy to identify the highest-ranking available LAR (see Table 2) [1].

- Method: The researcher must conduct a comprehensive informed consent discussion with the LAR, covering all elements required for the research study. The discussion must use language understandable to the LAR, and the LAR must be given sufficient time to ask questions.

- Documentation: The LAR's consent must be documented using a written consent form signed and dated by the LAR. Verbal consent from an LAR is not permissible if the study requires written consent [1]. The signature should be witnessed according to institutional policy.

4. Obtaining Subject Assent

- Purpose: To respect the autonomy of the subject, even when they lack full decision-making capacity.

- Procedure: The IRB will typically require that the assent of the subject be obtained whenever possible [1].

- Method: Actively solicit the subject's willingness to participate. Assent is defined as affirmative agreement; mere failure to object does not qualify as assent [1]. The process should be tailored to the subject's level of understanding.

- Handling Objections: If the subject objects to participation, whether to the determination of incapacity or to a decision made by the LAR, that objection prevails. The subject should not be enrolled, or if already enrolled, should be withdrawn, barring a court order to the contrary [1] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for LAR Consent

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for LAR Consent Protocols

| Item | Function in the LAR Consent Process |

|---|---|

| Capacity Assessment Tool | A structured set of questions or a guide (e.g., based on the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research or similar) used by researchers to consistently evaluate a subject's understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and choice regarding the study. |

| State Statute Excerpt/Guide | A document summarizing or containing the full text of the relevant state law defining the hierarchy of who can serve as an LAR. This is crucial for proper LAR identification [1]. |

| IRB-Approved LAR Consent Form | The full-length informed consent document, identical in content to the subject version, but with a dedicated signature line for "Legally Authorized Representative," including a field to specify their legal relationship to the subject and the authority under which they are acting. |

| Subject Assent Script | A simplified, easy-to-understand explanation of the research study used to seek affirmative agreement from subjects with impaired capacity. Multiple scripts may be needed for varying levels of comprehension. |

| Documentation of Capacity Assessment & LAR Determination | A standardized form or note-to-file template for recording the outcome of the capacity assessment, the formal determination of incapacity (if applicable), and the rationale for the identified LAR. |

| Witness Protocol & Short Form Consent | A procedure and corresponding short-form consent document for use when an LAR is unable to read the primary consent form, requiring an impartial witness to the verbal consent process [2]. |

The integration of Legally Authorized Representatives into the informed consent framework is a critical safeguard for protecting the rights and welfare of potential research subjects who lack decision-making capacity. Adherence to a structured protocol—beginning with a rigorous capacity assessment, moving through the precise identification of an LAR as defined by state law, and culminating in a thorough consent process with the LAR coupled with seeking the subject's assent—is fundamental to ethical research practice. By meticulously implementing these application notes and protocols, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure the ethical enrollment of this vulnerable population, thereby upholding the highest standards of research integrity while expanding the scope of scientific inquiry.

The evolution of ethical frameworks governing human subjects research represents a critical foundation for modern clinical trial design and implementation. This application note delineates the historical trajectory from the Nuremberg Code to contemporary FDA and Common Rule regulations, providing researchers with essential context for understanding current informed consent requirements. Particular emphasis is placed on implications for research involving legally authorized representatives, a population of special significance for investigators working with vulnerable subjects or in emergency medicine contexts. The ethical principles codified over the past seven decades continue to inform protocol development, institutional review board (IRB) functions, and the legal underpinnings of human subject protections across the research continuum.

Historical Foundations: The Nuremberg Code

Origin and Context

The Nuremberg Code emerged in 1947 from the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials, specifically during the "Doctors' Trial" of 23 Nazi physicians accused of conducting brutal experiments on concentration camp prisoners [5]. The trial judges developed this 10-point statement to define ethical boundaries for medical experimentation on human beings, establishing foundational principles that would reverberate through subsequent research ethics frameworks [6] [5]. The Code was created, in part, because the Nazi doctors argued that no international laws clearly distinguished between legal and illegal human experimentation, exposing a critical regulatory gap [5].

Core Principles

The Nuremberg Code established ten foundational principles for ethical research, with voluntary consent as its cornerstone [5]. The first principle unequivocally states that "the voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential," requiring that individuals have legal capacity to consent, exercise free power of choice, and possess sufficient knowledge to make an enlightened decision [6]. Additional principles emphasize that experiments should yield beneficial results for society unprocurable by other methods, should be based on animal experimentation and natural history knowledge, and should avoid unnecessary suffering [5]. The Code further establishes that risks should never exceed humanitarian importance, proper preparations must protect subjects, only qualified scientists should conduct research, subjects may terminate participation at any time, and scientists must be prepared to terminate experiments if risks materialize [5].

Table 1: Core Principles of the Nuremberg Code

| Principle Number | Key Focus | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Voluntary consent | Absolute requirement for informed, voluntary participation |

| 2 | Societal benefit | Research must yield meaningful, unprocurable results |

| 3 | Animal research basis | Justification through preliminary data and animal studies |

| 4 | Avoid unnecessary suffering | Minimization of physical and mental harm |

| 5 | No expectation of death/disability | Prohibition of inherently fatal research designs |

| 6 | Risk proportional to benefit | Risk threshold determined by humanitarian importance |

| 7 | Proper preparations and facilities | Adequate infrastructure for subject protection |

| 8 | Qualified researchers | Scientific expertise requirement |

| 9 | Subject termination right | Unconditional right to withdraw without penalty |

| 10 | Investigator termination duty | Obligation to halt experiments when risks emerge |

Historical Connections and Limitations

Historical analysis reveals that the Nuremberg Code drew significantly from earlier ethical frameworks, particularly the 1931 German Guidelines for human experimentation [6]. A point-by-point comparison shows substantial similarities, with six of the ten Nuremberg principles deriving from the 1931 Guidelines [6]. This historical connection was obscured during the trials, where prosecutors appeared ignorant of these pre-existing guidelines [6]. Unlike modern ethical codes that undergo regular revision, the Nuremberg Code has remained static since its creation, limiting its direct applicability to contemporary research contexts [6].

Modern Regulatory Framework

The Common Rule

The Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, known as the Common Rule, establishes comprehensive requirements for IRB review and approval of human subjects research [7]. Recently revised with effective dates in 2018-2019, the Common Rule mandates specific consent form requirements, including that clinical trials post approved consent forms to publicly available federal websites within 60 days of the last study visit [7]. The Revised Common Rule introduces the concept of "broad consent" for storage and secondary research use of identifiable private information and biospecimens, though institutional implementation varies [7]. For multi-site research, the Common Rule generally requires use of a single IRB review to streamline oversight processes [7].

FDA Regulations

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration provides complementary regulations governing clinical research, particularly for drug and device development. Recent FDA draft guidance addresses requirements for informed consent to begin with key information and present information in a manner that facilitates understanding [8]. These provisions, which align with similar requirements in the Revised Common Rule, emphasize the importance of clear, accessible consent processes rather than merely regulatory-compliant documentation [8]. When finalized, these regulations will further harmonize FDA requirements with the Common Rule, pursuant to the 21st Century Cures Act [8].

International Harmonization

Contemporary research ethics increasingly reflect international harmonization efforts, notably through the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines [9]. These international standards incorporate principles from the Nuremberg Code, Declaration of Helsinki, and other foundational documents while providing practical guidance for global research implementation [5]. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research have similarly developed a core set of 75 elements for participant consent documents, grouped into six categories to streamline consent forms while meeting regulatory requirements [9].

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Evolution

Table 2: Evolution of Key Elements in Human Research Ethics Frameworks

| Ethical Element | Nuremberg Code (1947) | Common Rule (1991-2019) | FDA/ICH Guidelines (2024) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consent Requirement | "Absolutely essential" voluntary consent | Written informed consent with specified elements | Beginning with key information; facilitating understanding |

| Vulnerable Populations | Not explicitly addressed | Additional protections for vulnerable subjects | Specific guidance for legally authorized representatives |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment | Risk must be justified by humanitarian importance | Minimization of risks; reasonable risk-benefit ratio | Systematic assessment of risks and benefits |

| Researcher Qualifications | "Qualified persons" requirement | IRB assessment of investigator qualifications | GCP training requirements and documentation |

| Withdrawal Rights | Unconditional right to terminate participation | Right to discontinue without penalty or loss of benefits | Clear procedures for withdrawal and data handling |

| Oversight Mechanism | Individual investigator responsibility | Institutional Review Board review and approval | IRB/IEC review plus regulatory agency oversight |

| Documentation | Implicit in consent requirement | Comprehensive documentation requirements | Written, signed, dated informed consent forms |

Legally Authorized Representatives in Research

Context and Applicability

Research involving legally authorized representatives (LARs) occurs when potential subjects lack capacity to provide independent informed consent due to cognitive impairment, developmental disability, psychiatric conditions, or medical emergencies [4]. The use of LARs represents a practical application of the ethical principle of respect for persons while enabling research participation for those who cannot consent for themselves. This approach acknowledges the relational nature of decision-making in vulnerable populations while maintaining ethical safeguards [9].

Regulatory Framework for LAR Consent

Modern regulations permit LAR consent under specific conditions. The Tri-Council Policy Statement in Canada and similar international guidelines recognize that certain research would be impossible without LAR involvement, particularly for conditions that directly impair decision-making capacity [9]. Emergency research represents a special case where consent may be obtained from LARs after initiation of study procedures, provided that strict criteria are met: the subject must have a life-threatening condition, available treatments are unproven or unsatisfactory, and obtaining prospective consent is not feasible [4]. The Common Rule specifies requirements for LAR-based consent, including that the representative have adequate authority under applicable law and that consent reflects the potential subject's presumed preferences or best interests [7].

Practical Implementation Protocol

Protocol Title: Consent Procedure Using Legally Authorized Representatives

Purpose: To establish standardized procedures for obtaining and documenting informed consent from legally authorized representatives for research subjects who lack decision-making capacity.

Materials:

- IRB-approved informed consent form designed for LAR use

- Capacity assessment tools (e.g., MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research)

- Documentation of LAR authority (e.g., healthcare power of attorney, guardianship papers)

- Educational materials explaining study procedures in LAR-accessible language

Procedure:

Determine Need for LAR Involvement

- Assess potential subject's decision-making capacity using standardized tools

- Document assessment findings in research record

- Confirm absence of capacity for informed consent decision-making

Identify Appropriate LAR

- Establish hierarchy according to state law (typically: court-appointed guardian, healthcare agent, spouse, adult children, parents, adult siblings)

- Verify LAR identity and authority through documentation

- Document LAR relationship to potential subject

Consent Discussion with LAR

- Conduct consent discussion in private setting

- Present information in language appropriate to LAR's understanding

- Emphasize LAR's role as surrogate decision-maker

- Explain difference between research and clinical care

- Discuss potential risks, benefits, and alternatives

- Highlight right to withdraw subject without penalty

- Allow sufficient time for LAR questions and consideration

Documentation

- Obtain LAR signature and date on IRB-approved consent form

- Include signature of person obtaining consent

- Provide copy of signed consent form to LAR

- File original in research record

Ongoing Communication

- Provide ongoing information about study progress to LAR

- Re-consent for significant study changes or protocol modifications

- Inform LAR of new information that may affect continued participation

Special Considerations:

- When subjects regain capacity, seek direct consent for continued participation

- In emergency research, follow exception from informed consent requirements if applicable

- For pediatric populations, follow specific parental permission and child assent requirements

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Consent Process Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Informed Consent Process Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Understanding Assessment Tools | Quantifies participant comprehension of consent information | Evaluation of key information presentation effectiveness in consent forms |

| Readability Analysis Software | Assesses reading level and complexity of consent documents | Ensuring consent forms meet recommended 6th-8th grade reading level |

| Consent Process Templates | Standardizes information disclosure across sites and studies | Implementing core consent elements identified by CIHR [9] |

| Digital Consent Platforms | Facilitates multimedia consent presentation and documentation | Testing impact of interactive content on understanding and retention |

| LAR Authority Verification Checklists | Ensures proper identification of legally authorized representatives | Standardizing documentation requirements for surrogate decision-makers |

| Vulnerable Population Assessment Tools | Identifies needs for additional consent process modifications | Adapting processes for cognitively impaired, pediatric, or non-English speaking populations |

Regulatory Evolution Pathway Visualization

Diagram Title: Evolution of Research Ethics Regulations

Legally Authorized Representative Decision Pathway

Diagram Title: LAR Consent Decision Pathway

The historical trajectory from the Nuremberg Code to contemporary FDA and Common Rule regulations demonstrates an evolving understanding of research ethics while maintaining foundational commitments to voluntary participation, comprehensive information disclosure, and subject protection. For researchers working with populations requiring legally authorized representatives, this historical context provides essential grounding for ethical protocol design and implementation. Modern frameworks have refined rather than replaced core Nuremberg principles, adapting them to complex contemporary research environments while preserving their fundamental ethical commitments. Continued attention to both historical foundations and emerging regulatory guidance remains essential for maintaining public trust and advancing ethical research practices across all participant populations.

Application Notes: Operationalizing Ethical Principles in Informed Consent

The informed consent process is a fundamental application of core ethical principles in human subjects research, serving as both a legal requirement and a continuous ethical dialogue. For research involving legally authorized representatives (LARs), who make decisions on behalf of potential participants who lack decision-making capacity, this process carries additional complexity and moral weight. The following application notes detail how the principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence, and non-domination can be operationalized when obtaining consent from LARs.

Respect for Autonomy Through the Legally Authorized Representative

Respect for autonomy recognizes the right of individuals to make informed, voluntary decisions about their own lives. When a potential research participant cannot exercise this right directly due to incapacity, the role transfers to a legally authorized representative who is entrusted to make decisions reflecting the participant's would-be wishes and best interests.

- Substituted Judgment Standard: Guide LARs to make decisions based on the participant's known values, beliefs, and prior expressed wishes, rather than the LAR's own preferences [10]. The consent process must facilitate this by helping the LAR understand what the participant would have chosen if capable.

- Voluntariness Assurance: The LAR's decision must be free from coercion, undue influence, or pressure. This is particularly crucial in emotionally stressful situations, such as when the participant is critically ill [11] [12]. Researchers must explicitly state that participation is voluntary and that declining will not affect the quality of clinical care.

- Ongoing Process: Consent is not a single event captured by a signature. It is a continuous process that should be reaffirmed throughout the study, especially if the participant's condition changes or new information emerges [13] [11]. This is vital for maintaining the autonomy of the participant through their representative.

Beneficence in Risk-Benefit Analysis and Communication

The principle of beneficence requires researchers to maximize potential benefits and minimize potential harms for the research participant. When working with LARs, this entails a rigorous and transparent risk-benefit analysis.

- Comprehensive Risk Disclosure: Clearly explain all foreseeable physical, psychological, social, and economic risks. For LARs of vulnerable individuals, this disclosure must be especially thorough and may require discussing risks specific to the participant's condition [10] [12].

- Honest Benefit Portrayal: Distinguish between direct therapeutic benefits for the participant and the broader, generalizable knowledge that may benefit future patients. Avoid the therapeutic misconception, where the LAR might mistakenly believe the primary purpose of the research is to provide direct treatment [12].

- Proportionality Assessment: The research protocol itself must be designed so that the risks are reasonable in relation to the potential benefits to the participant and the importance of the knowledge to be gained [12]. The researcher's role is to present this balance honestly to the LAR.

Non-Domination in Mitigating Power Imbalances

Non-domination, as a refinement of the justice principle, focuses on protecting individuals from arbitrary power and coercion. In the LAR consent process, this involves actively identifying and mitigating inherent power dynamics.

- Addressing Structural Vulnerabilities: LARs for individuals with cognitive impairments or rare diseases may feel particularly dependent on the healthcare system and hesitant to refuse a researcher's request [14] [10]. Researchers must be trained to create an environment where the LAR feels empowered to ask questions and decline participation.

- Combatting Therapeutic Misconception: Proactively correct the assumption that the research is solely for the participant's personal treatment. This misconception can dominate a LAR's decision-making, preventing a truly informed choice [12].

- Clarity on Legal Rights and Protections: Explicitly inform LARs of their rights, including the right to withdraw the participant from the study at any time without penalty, and the contact information for the Institutional Review Board (IRB) [11] [12]. This knowledge empowers the LAR against potential arbitrary use of power by the research institution.

Empirical data on the informed consent process helps identify areas for improvement, which is critical when the process is mediated by a LAR. The following tables summarize key findings from recent research.

Table 1: Research Staff Perspectives on the Informed Consent Process (Survey of 115 Staff) [15]

| Concern Area | Percentage of Staff Reporting | Implication for LAR Consent |

|---|---|---|

| Confidence in facilitating consent | 74.4% felt confident or very confident | Highlights need for specialized LAR training for remaining ~25% |

| Concerns about participant understanding | 56% were concerned about understanding of complex information | Suggests LAR comprehension may be similarly challenged, requiring enhanced communication |

| Perception of information materials | 63% felt information leaflets were too long and/or complicated | Underscores need for LAR-specific, plain-language summaries |

| Time constraints as a barrier | 40% felt time pressure was a barrier | LAR decisions often require more time; protocols must allocate adequate time |

Table 2: Participant Preferences in Digital Health Research Consent (Survey of 79 Participants) [16]

| Factor Influencing Preference | Impact on Preference for Modified (More Readable) Text | Application to LAR Communication |

|---|---|---|

| Character Length | Longer original text → less preference for original (P<.001) | Prioritize concise, essential information for LARs |

| Content Type | Text explaining risks significantly preferred in modified form (P=.03) | Use special care and clarity when communicating risks to LARs |

| Age | Older participants tended to prefer original text more than younger (P=.004) | Tailor communication format to the LAR's demographic; avoid assumptions |

Experimental Protocols for Ethical LAR Informed Consent

Protocol: A Multi-Method Consent Process Discussion

This protocol provides a structured methodology for the initial consent discussion between the researcher and the Legally Authorized Representative.

Objective: To ensure the LAR fully comprehends the study's purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives, thereby enabling a decision that respects the participant's autonomy and is free from domination.

Materials:

- IRB-approved consent form and LAR information sheet.

- Visual aids (e.g., flowcharts, simplified diagrams).

- Teach-back method checklist.

- Documentation form (for noting the discussion, questions asked, and confirmation of understanding).

Workflow:

- Pre-Discussion Preparation: Provide the LAR with the consent form and a short, plain-language summary in advance of the meeting.

- Environment Setup: Conduct the discussion in a private, quiet setting with minimal interruptions. Allocate a minimum of 30-60 minutes for the discussion.

- Verbal Explanation & Dialogue:

- Introduce the study's purpose and clarify that it is research, not standard therapy.

- Systematically review all key elements of the consent form using the second person ("You have the right to...") [12].

- Use visual aids to explain complex concepts like randomization or data handling.

- Pause frequently to check for understanding and invite questions.

- Teach-Back Assessment: Ask the LAR to explain in their own words their understanding of a key aspect of the study, such as the main procedures or the primary risk [10]. This assesses comprehension more effectively than simply asking "Do you understand?"

- Documentation: After the discussion and before signature, document the key points covered, the questions raised by the LAR, and the use of the teach-back method in the participant's file or a research note [14].

Diagram 1: LAR Consent Discussion Workflow

Protocol: Evaluating and Improving Consent Form Readability

This protocol outlines a method for developing and refining consent forms to ensure they are accessible to Legally Authorized Representatives of diverse educational backgrounds.

Objective: To create consent materials that meet the recommended 6th to 8th-grade reading level and are responsive to user feedback, thereby promoting true understanding and autonomous decision-making.

Materials:

- Draft consent form.

- Readability analysis software (e.g., online readability calculators).

- Access to a panel of potential user reviewers (e.g., from a community advisory board).

Workflow:

- Initial Drafting: Compose the consent form using plain language principles: short sentences, common words, and active voice.

- Readability Analysis: Input the consent form text into readability software to obtain metrics like Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Reading Ease [11]. The target is ≤ 8th-grade level.

- Text Modification: Rewrite sections that exceed the target reading level. Strategies include:

- Replacing complex jargon with simpler terms.

- Breaking long sentences into shorter ones.

- Using bullet points for lists.

- User-Centered Feedback (Prototyping): Present pairs of text snippets (original vs. modified) to a small group of individuals representing the LAR demographic. Ask them to indicate their preference and explain why [16]. This identifies which versions are perceived as clearer.

- Finalization and IRB Approval: Integrate the feedback to create the final consent form and submit it, along with the readability metrics, for IRB review and approval.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ethical Consent Research

Table 3: Key Resources for Implementing and Studying the LAR Informed Consent Process

| Tool / Resource | Function in Consent Research | Example / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Teach-Back Method | A validated health literacy tool to confirm understanding by asking individuals to explain information in their own words [10]. | After explaining study withdrawal procedures, the researcher asks the LAR, "Can you tell me in your own words what you would do if you wanted to stop the participant's involvement in the study?" |

| Readability Software | Quantitatively assesses the reading grade level and ease of written materials, such as consent forms and information sheets [16] [11]. | Using tools like the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level test in Microsoft Word or online calculators to ensure forms meet the ≤ 8th-grade reading level target. |

| Informed Consent Checklist | A standardized list of required elements (e.g., risks, benefits, voluntariness) to ensure all are thoroughly discussed and documented [17] [12]. | Used by researchers to self-monitor the consent discussion and by IRBs to verify protocol completeness during review. |

| Verbal Consent Script | A structured script for obtaining consent verbally, often used in minimal-risk research or when written consent is impractical [14]. | Provides a standardized dialogue for phone-based consent with an LAR, ensuring consistency and completeness across participants. |

| Experimental Subject's Bill of Rights | A legally mandated document in some jurisdictions that outlines the rights of every research participant, which must be provided to the LAR [17]. | Serves as a foundational document to reinforce the principle of non-domination by explicitly stating the LAR's and participant's rights at the outset. |

Within clinical research, the ethical enrollment of participants hinges on a robust informed consent process. This process becomes complex when potential participants belong to vulnerable populations, defined as groups at an increased risk for health problems and health disparities due to a range of social, economic, and environmental factors [18]. For researchers investigating the legally authorized representative (LAR) informed consent process, a precise and systematic identification of these vulnerabilities is paramount. An LAR is an individual who provides consent on behalf of an adult who lacks the mental capacity to make decisions for themselves [2]. This protocol provides detailed application notes to aid researchers in identifying participants who may require LAR consent due to vulnerabilities impacting their decision-making capacity, thereby ensuring ethical rigor and regulatory compliance in studies focused on LAR-led informed consent.

Vulnerability in clinical research is multidimensional. It is shaped by factors such as age, education, health status, and socioeconomic conditions, which can be exacerbated by life events like abuse or neglect [18]. For the purpose of operationalizing assessments in LAR-informed consent research, vulnerabilities can be categorized into three core domains: physical, psychological, and social. Individuals often experience overlapping vulnerabilities across these domains, which compounds their risk and complicates the consent process [19]. The following tables summarize the key characteristics and prevalence data for each domain.

Table 1: Physical and Psychological Vulnerabilities

| Vulnerability Domain | Key Characteristics | Example Populations | Quantitative Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Vulnerabilities [19] [20] | Presence of chronic illness, disability, or communication barriers that impede the ability to provide independent informed consent. | High-risk mothers & infants, the chronically ill (e.g., respiratory disease, diabetes, cancer), disabled persons, elderly, persons with HIV/AIDS [19]. | - ≈87% of those ≥65 years have ≥1 chronic condition; 67% have ≥2 [19].- Chronic conditions affect ~133M Americans (2005), projected to rise to 171M by 2030 [19]. |

| Psychological Vulnerabilities [19] [20] | Conditions affecting cognitive function, judgment, or emotional state, impairing understanding of research risks/benefits. | Persons with chronic mental conditions (schizophrenia, bipolar, major depression), alcohol/substance dependency, dementia, developmental disorders [19]. | - 17.4M (32.9%) adults with disabilities experience frequent mental distress [20].- >50% of incarcerated individuals have a mental health disorder [20]. |

Table 2: Social Vulnerabilities and Enabling Factors

| Vulnerability Domain | Key Characteristics | Example Populations | Quantitative Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Vulnerabilities [19] [20] | Social, economic, and environmental disadvantages that create barriers to healthcare and research participation. | Homeless, incarcerated, racial/ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+, immigrants/refugees, victims of human trafficking, rural residents [19] [20]. | - Nonwhite, unemployed, uninsured women (45-64) with lower income/education report poorest health [19].- Incarceration rate: 810 per 100,000 U.S. adults [20]. |

| Enabling Factors of Vulnerability [19] | Systemic and economic factors that directly limit access to care and the capacity to engage in research. | Economically disadvantaged, uninsured, those lacking a regular source of care. | - The uninsured are 7x less likely to get needed care and 4.5x more likely to not fill prescriptions [19].- 1 in 5 U.S. adults has multiple risk factors for unmet health needs [19]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Vulnerability and Capacity

A standardized protocol is essential for consistently identifying vulnerabilities that may necessitate LAR consent. The following workflow provides a methodological approach for researchers specializing in the LAR informed consent process.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for assessing participant vulnerability and determining the need for LAR consent. LAR: Legally authorized representative.

Protocol 1: Initial Vulnerability Screening

Objective: To systematically identify participants who may have physical, psychological, or social vulnerabilities that could impair their capacity to provide independent informed consent. Materials: Study participant records, pre-screening questionnaire, vulnerability assessment checklist (derived from Tables 1 & 2). Methodology:

- Pre-Screening Questionnaire: Prior to the formal consent process, administer a questionnaire designed to identify potential vulnerabilities. This should include questions about:

- Checklist Application: Use a standardized checklist based on the vulnerability domains (Tables 1 and 2) to flag participants who meet one or more criteria. The presence of a vulnerability does not automatically preclude self-consent but triggers a formal capacity assessment. Data Analysis: Categorize identified vulnerabilities by domain (physical, psychological, social). Document the rationale for proceeding to a capacity assessment.

Protocol 2: Structured Decision-Making Capacity Assessment

Objective: To evaluate a participant's understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and ability to communicate a choice regarding research participation. Materials: MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) or similar validated instrument, audio recorder (with consent), documentation form. Methodology:

- Structured Interview: Conduct a semi-structured interview using a validated tool like the MacCAT-CR. This assesses four key abilities:

- Understanding: Ability to comprehend the study's purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits.

- Appreciation: Ability to recognize how the research applies to one's own situation.

- Reasoning: Ability to logically weigh the options of participation versus non-participation.

- Expression of a Choice: Ability to communicate a stable decision clearly.

- Scenario-Based Questions: Present the participant with a simplified summary of the research and ask them to explain it back in their own words, state the potential downsides and benefits for themselves, and explain why they would or would not choose to participate. Data Analysis: Score the assessment based on the tool's guidelines. A finding of impaired capacity in one or more domains should trigger the initiation of the LAR consent process, in accordance with applicable state or institutional law [2] [21].

Protocol 3: LAR Identification and Consent Execution

Objective: To identify the correct Legally Authorized Representative and execute the informed consent process in accordance with regulatory and state-specific laws. Materials: Institutional policy documents, state statute guidelines (e.g., Missouri Revised Statutes 431.064 [21]), LAR consent form. Methodology:

- Hierarchy Verification: Consult applicable law to determine the order of priority for LAR designation. For example, the state of Missouri specifies the following order: spouse, adult child, parent, sibling, then relative by blood or marriage [21]. This priority order must be followed without deviation barring specific, documented circumstances (e.g., spouse is physically incapable or whereabouts unknown).

- LAR Informed Consent Process: The researcher must conduct the full informed consent discussion with the LAR. This process must include all basic elements of informed consent as per 45 CFR 46.116(a), such as a statement that the study involves research, an explanation of purposes and procedures, a description of foreseeable risks and benefits, and a statement that participation is voluntary [22].

- Documentation: The LAR must sign the IRB-approved consent document. The researcher should also document in the study records the specific rationale for using an LAR and the verification of the LAR's authority to consent [2] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers conducting studies on the LAR informed consent process, specific tools and materials are essential for ensuring methodological rigor and ethical compliance.

Table 3: Essential Materials for LAR Informed Consent Research

| Item/Tool | Function/Benefit | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Capacity Assessment Tool (e.g., MacCAT-CR) | Provides a standardized, psychometrically valid method for assessing a participant's decision-making capacity. | Critical for producing objective, reproducible data on capacity impairment; strengthens research validity and defends LAR activation decisions. |

| Vulnerability Screening Checklist | Operationalizes the identification of at-risk participants based on physical, psychological, and social domains. | Ensures systematic screening across all participants; can be customized based on specific study population (e.g., geriatrics, psychiatry). |

| IRB-Approved LAR Consent Form Template | Ensures regulatory compliance by including all required elements of informed consent and signature lines for the LAR and witness if needed. | Prevents protocol deviations; templates often available via institutional IRB resource centers [2]. Must not contain exculpatory language [22]. |

| State Statute Guide on LAR Hierarchy | Provides the legally mandated order of authority for identifying a participant's LAR. | Essential for research legality; prevents consent invalidation. Researchers must use the most current version of their local statutes [21]. |

| Documentation & Audit Trail Protocol | Creates a detailed record of the screening, capacity assessment, and LAR consent process. | Serves as primary data for research on LAR processes; vital for regulatory audits and addressing IRB queries. |

Within clinical research, obtaining valid informed consent is a foundational ethical and legal requirement. This process becomes complex when potential participants have impairments affecting their decision-making abilities. A core challenge is determining when an individual lacks the capacity to provide autonomous consent, necessitating the involvement of a Legally Authorized Representative (LAR). This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for researchers on assessing patient capacity and implementing LAR-informed consent processes, framed within broader research on enhancing the ethical rigor of LAR consent.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

A clear understanding of the distinction between key terms is essential for proper application.

Table 1: Key Definitions in Consent and Capacity

| Term | Definition | Determining Authority |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity | A functional, clinical assessment that an individual is or is not capable of making a specific medical or research decision at a given time [23]. | Qualified healthcare professional (e.g., physician, physician assistant, NP) [23]. |

| Competency | A legal status declaring an individual's ability to participate in legal proceedings; broadly referred to as "legal capacity" in modern healthcare contexts [24] [23]. | A court or judge [24] [23]. |

| Informed Consent | The systematic process of patient/participant education and decision-making regarding a treatment or research procedure, involving discussion of nature, risks, benefits, and alternatives [23]. | Researcher or clinician, following a comprehensive discussion with a capable individual or their LAR. |

| Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) | An individual or entity authorized by law to consent on behalf of a prospective participant who lacks capacity [2]. | Defined by state law; often a guardian, spouse, or family member. |

Critically, capacity is decision-specific. A patient with some cognitive impairment may retain the capacity to consent to a simple blood draw but lack the capacity to understand a complex clinical trial [24]. Capacity can also be intermittent or fluctuating, influenced by factors like medication, fatigue, or acute illness [24] [23].

Quantitative Data on Capacity and Consent Triggers

Research and clinical guidelines have identified specific triggers that should prompt a formal capacity assessment. The following table synthesizes this data for easy reference.

Table 2: Quantitative Clinical Triggers for Capacity Assessment

| Trigger Category | Specific Indicators | Rationale & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Decision-Making Patterns | - Blanket acceptance or refusal of care without rationale [23]. - Inability to voice a consistent decision [23]. - Providing excessive or inconsistent reasons for refusing care [23]. | Suggests a lack of appreciation or understanding of the situation and consequences. |

| Behavioral & Emotional State | - Hyperactivity, disruptive behavior, or agitation [23]. - Labile emotions or affect [23]. - Presence of hallucinations [23]. - Clinical intoxication [23]. | Acute behavioral health or neurological issues can temporarily impair reasoning and appreciation. |

| Cognitive & Functional Status | - New inability to perform activities of daily living [23]. - Absence of questions about complex treatment [23]. - Sensory deficits that impair understanding [24]. | Indicates a potential decline in the cognitive abilities required to process information and communicate a choice. |

Protocol for Assessing Decision-Making Capacity

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for conducting a clinically sound capacity assessment, based on established ethical principles and legal standards.

Experimental Protocol: Clinical Capacity Assessment

Objective: To determine if a potential research participant possesses the mental capacity to provide independent informed consent for a specific clinical trial.

Principles Governing Proportionality: The level of capacity required is proportional to the risk and complexity of the research. As the seriousness of the consequences increases, so too must the level of capacity required for a finding of competence [25]. This is often explained as balancing patient autonomy with their wellbeing, or as leaving a greater margin for error when the stakes are high [25].

Materials:

- Patient/participant medical records.

- Informed consent document for the proposed research.

- Capacity assessment checklist (e.g., based on Table 3 domains).

Procedure:

- Preparation: Review the patient's medical history, including any cognitive or psychiatric diagnoses, medications, and baseline functional status. Familiarize yourself with the key elements of the research protocol, especially risks, benefits, and alternatives.

- Environment Setup: Conduct the assessment in a quiet, private environment to minimize distractions. Ensure the participant has any necessary sensory aids (e.g., glasses, hearing aid).

- Capacity Domain Assessment: Engage the participant in a structured interview. The following table outlines the core functional domains to assess and the corresponding lines of questioning.

Table 3: Assessing the Functional Domains of Capacity

| Domain | Assessment Question | Sample Investigator Prompts |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding | Can the participant grasp the fundamental information about the research? | "Please tell me in your own words what this study involves." "What are the major risks or benefits you are expecting?" |

| Appreciation | Can the participant apply the information to their own personal situation? | "Why do you think this research is being offered to you?" "What do you believe will happen if you decide not to participate?" |

| Reasoning | Can the participant logically compare alternatives and consequences? | "Can you talk me through how you reached your decision?" "What makes this option better for you than the alternative treatments?" |

| Expression of Choice | Can the participant communicate a clear and stable decision? | "Having discussed everything, what is your decision about participating?" Re-assess consistency over a short period (e.g., after a break). |

- Documentation: Thoroughly document the assessment in the participant's record. Include the date, time, specific questions asked, the participant's responses, and the clinical justification for the final determination of capacity or lack thereof [23].

- Determination & Next Steps:

- If Capacity is Intact: The participant may proceed with the standard informed consent process.

- If Capacity is Impaired: The researcher must not proceed with enrollment based on the participant's consent. The process for seeking consent from an LAR must be initiated (see Section 5.0). If the impairment may be temporary (e.g., delirium, intoxication), the assessment should be repeated at a later time [24].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the clinical and legal pathways for determining the appropriate consent process.

Protocol for LAR-Informed Consent Process

When a participant lacks clinical capacity, the LAR becomes the decision-maker. This protocol outlines the steps for engaging an LAR.

Experimental Protocol: LAR Consent

Objective: To obtain valid informed consent for research participation from a Legally Authorized Representative on behalf of an incapacitated adult.

Materials:

- IRB-approved informed consent document.

- Signature lines for the LAR and an impartial witness (if required) [2].

- Documentation of the participant's lack of capacity.

Procedure:

- Verify LAR Authority: Confirm the individual's legal authority to serve as an LAR per state law. This may be a court-appointed guardian, a person designated in a durable power of attorney for healthcare, or a family member according to a statutory hierarchy [24].

- Conduct Consent Discussion: The individual conducting the informed consent discussion (e.g., principal investigator) must engage the LAR in a comprehensive conversation. This discussion must cover all elements of the informed consent form, including the purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, alternatives, and the voluntary nature of participation.

- Assess LAR Understanding: Employ the same principles of assessing understanding, appreciation, and reasoning as with a participant (Table 3) to ensure the LAR can fulfill their surrogate role.

- Document Consent: The LAR must sign and date the IRB-approved consent form. The individual who obtained the consent must also sign.

- Witness Involvement (if applicable): An impartial witness (e.g., a nurse not on the study team) is required in specific circumstances, such as when using a "short form" consent process for a participant who cannot read the form due to low literacy, visual impairment, or need for an unexpected translation [2]. The witness attests that the information was accurately explained and that consent was voluntary.

- Honor Participant Assent: Even when lacking capacity, the participant's wishes and feelings should be respected. If the participant objects, this objection should be honored unless the research intervention holds out the prospect of direct benefit and is unavailable outside the study [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and conceptual tools essential for conducting ethical research with participants of impaired capacity.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for Capacity and Consent Research

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Structured Capacity Assessment Tools | Validated instruments (e.g., MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research) provide a standardized framework for evaluating the four capacity domains, improving reliability and objectivity. |

| IRB-Approved LAR Consent Forms | Consent documents must include specific signature lines for the LAR, ensuring the legality and regulatory compliance of the surrogate consent process [2]. |

| Supported Decision-Making (SDM) Agreements | An emerging alternative to guardianship, SDM allows individuals with disabilities to retain decision-making rights with the help of trusted advisors, promoting autonomy as a less restrictive alternative [24]. |

| Impartial Witness | An individual independent of the research study who observes the consent process with an LAR or participant in specific scenarios (e.g., short-form consent) to attest to the integrity of the process [2]. |

Within the framework of legally authorized representative (LAR) informed consent process research, understanding the nuanced legal standards for evaluating consent validity is paramount. These standards establish the criteria by which courts and regulatory bodies assess whether consent was properly obtained, particularly when LARs make decisions on behalf of individuals who lack capacity. The three predominant standards—Subjective, Reasonable Patient, and Reasonable Clinician—provide distinct analytical frameworks for evaluating whether adequate information was provided and properly understood during the consent process [26] [22].

For researchers investigating LAR decision-making processes, these standards represent critical methodological frameworks for designing studies, assessing consent quality, and analyzing how surrogate decision-makers comprehend and balance risks, benefits, and alternatives when authorizing participation in research or treatment. The choice of standard significantly influences how we evaluate the effectiveness of consent processes and the adequacy of information disclosure in both clinical and research settings involving vulnerable populations.

Theoretical Foundations

The Subjective Standard

The Subjective Standard focuses exclusively on what the specific patient or LAR actually understood and considered important when providing consent. This standard requires evaluating whether the disclosure enabled that particular individual to make an informed decision based on their unique values, preferences, and circumstances [26]. Under this framework, the adequacy of information disclosure is measured against the individual's personal informational needs, regardless of whether a reasonable person would have found the disclosure sufficient.

In LAR consent research, this standard presents methodological challenges as it requires investigators to ascertain the specific decision-making factors and comprehension levels of each representative. The subjective standard aligns most closely with the philosophical foundations of informed consent that emphasize individual autonomy and respect for personal values [26]. However, its application in research is complicated by the need to document the specific understanding and priorities of each LAR, which may vary significantly across different representatives.

The Reasonable Patient Standard

The Reasonable Patient Standard establishes an objective benchmark based on the information a hypothetical "reasonable patient" would require to make an informed decision. This standard does not focus on the specific individual but rather on what information would be material to a typical patient in similar circumstances [26]. The materiality threshold encompasses any information that would significantly affect the decision-making process of a reasonable person.

This standard has gained prominence in judicial reasoning, particularly since the landmark case of Canterbury v. Spence (1972), which shifted focus from physician-centered disclosure to patient-centered information needs. For LAR consent research, this standard provides a more consistent and measurable framework for evaluating consent processes, as it establishes objective criteria for necessary disclosure elements rather than attempting to ascertain individual subjective priorities.

The Reasonable Clinician Standard

The Reasonable Clinician Standard (also known as the professional standard) evaluates consent based on what a reasonable medical professional would typically disclose under similar circumstances. This traditional approach defers to medical judgment in determining the appropriate scope and depth of information disclosure [26]. The standard reflects a more paternalistic approach to medical decision-making, where physicians retain significant discretion regarding what information to share.

In contemporary practice, this standard has been largely superseded by patient-centered approaches, though it remains influential in certain jurisdictions and specialized medical contexts. For LAR consent researchers, this standard raises important questions about the tension between professional discretion and patient autonomy, particularly when surrogates make decisions for vulnerable individuals who cannot express their own preferences.

Comparative Analysis of Legal Standards

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Consent Legal Standards

| Evaluation Dimension | Subjective Standard | Reasonable Patient Standard | Reasonable Clinician Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Actual understanding of specific patient/LAR | Information needs of hypothetical reasonable patient | Customary disclosure practices of medical profession |

| Measurement Approach | Individual-specific assessment | Objective, patient-centered materiality | Professional norms and customs |

| Research Methodologies | Qualitative interviews, comprehension assessment | Surveys of patient preferences, outcome studies | Practice guidelines analysis, expert consensus |

| Strengths | Maximizes individual autonomy, respects personal values | Consistent application, prevents under-disclosure | Respects clinical judgment, accounts for medical complexity |

| Limitations | Difficult to administer consistently, variable standards | May not address individual variations in preferences | Potentially paternalistic, may limit patient autonomy |

| Application in LAR Context | Assesses actual LAR understanding and decision factors | Establishes baseline disclosure requirements for surrogates | Guides professionals in LAR communication practices |

Experimental Protocols for Consent Standard Evaluation

Protocol 1: Assessing Information Comprehension Under Different Standards

Purpose: To evaluate how effectively LARs comprehend and retain essential consent information when disclosures are structured according to different legal standards.

Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit three distinct cohorts of legally authorized representatives (n=45 each) including family members, court-appointed guardians, and healthcare agents.

- Stimulus Development: Create three parallel consent documentation sets—(1) Subjective-standard tailored communications, (2) Reasonable-patient standardized materials, and (3) Clinician-standard professional disclosures.

- Implementation: Administer pre-intervention baseline knowledge assessment, deliver standardized educational session, provide consent materials according to assigned protocol, and conduct post-intervention comprehension testing at 24 hours and 1 week.

- Metrics: Measure knowledge retention accuracy, risk-benefit understanding, alternative treatment awareness, and decision uncertainty.

Data Analysis: Employ mixed-effects modeling to account for within-subject changes over time and between-group differences in comprehension trajectories, controlling for representative characteristics and prior medical decision-making experience.

Protocol 2: Decision Quality Assessment Across Standards

Purpose: To evaluate how different consent standards influence the quality of decisions made by LARs, measured by alignment with patient values and clinical outcomes.

Methodology:

- Simulated Decision Scenarios: Develop eight complex medical decision scenarios involving common surrogate decision contexts (dementia progression, terminal illness, severe disability, etc.).

- Participant Groups: Recruit 240 LARs stratified by relationship type (spouse, adult child, parent, unrelated guardian).

- Intervention Arms: Randomize participants to receive consent information structured according to one of the three legal standards.

- Outcome Measures: Assess decision congruence with documented patient values (when available), decision confidence, regret scales, and consultation-seeking behaviors.

- Longitudinal Follow-up: Administer decision regret scale at 1-month and 3-month intervals to evaluate persistence of decision quality.

Analysis Plan: Conduct multinomial logistic regression to identify factors associated with high-quality decisions under each standard, including interaction effects between standard type and representative characteristics.

Research Reagent Solutions for Consent Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Consent Standard Investigation

| Research Tool | Specifications | Application in Consent Research |

|---|---|---|

| Decisional Conflict Scale (DSC) | 16-item validated instrument measuring personal uncertainty in healthcare decision making | Quantifies LAR decision difficulty under different consent standards |

| Modified MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool | Semi-structured interview evaluating understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and choice | Assesses LAR decision-making capacity and comprehension quality |

| LAR Information Preference Inventory | 24-item questionnaire measuring information priorities across clinical domains | Identifies disclosure elements most valued by surrogates across standards |

| Decision Regret Scale | 5-item post-decision evaluation tool measuring distress and remorse | Tracks longitudinal outcomes of consent processes under different standards |

| Standardized Patient Scenarios | Validated clinical vignettes with embedded decision conflicts | Provides consistent experimental stimuli for comparing consent standards |

| Video-Recorded Consent Encounter Protocol | Structured documentation of consent conversations with communication analysis | Enables micro-analysis of information exchange under different standards |

Integration with Legally Authorized Representative Research

The application of these three legal standards to LAR consent processes raises distinctive considerations beyond routine clinical consent. When representatives make decisions for others, the Subjective Standard must account for both the representative's understanding and their accurate representation of the patient's values and preferences [2]. This dual consideration creates complex methodological challenges for researchers evaluating consent quality in surrogate decision-making.

The Reasonable Patient Standard in LAR contexts must be adapted to consider what a reasonable surrogate would find material when making decisions for another person, accounting for the unique responsibilities and perspectives of representation [26]. This may include information about quality of life considerations, caregiving implications, and long-term prognosis that might be weighted differently when making decisions for oneself versus for another.

The Reasonable Clinician Standard applied to LAR interactions emphasizes the professional's duty to ensure representatives adequately understand the implications of decisions they are making on behalf of others [22]. This includes assessing representative comprehension and ensuring they can articulate the potential benefits, risks, and alternatives in a manner consistent with the patient's best interests and previously expressed values.

Data Synthesis and Analytical Framework

The investigation of legal standards within LAR consent research requires sophisticated analytical approaches that account for both quantitative metrics of understanding and qualitative dimensions of decision-making quality. Future research should develop integrated assessment frameworks that combine comprehension scores, value congruence measures, and longitudinal decision regret to provide comprehensive evaluation of how different standards perform in actual practice.

Research in this domain must also consider contextual factors including the type of medical decision, urgency, relationship between representative and patient, and previous experience with healthcare decision-making. These variables likely interact with consent standards to produce different outcomes across the spectrum of surrogate decision-making contexts encountered in clinical practice and research settings.

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to the LAR Consent Process

Within the framework of research involving cognitively impaired populations, the process of obtaining informed consent via a Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) is a critical ethical and legal safeguard. This protocol details the systematic preparation of documents and training of research staff, a foundational element for the integrity of the LAR-informed consent process. Proper pre-consent preparation ensures compliance with federal regulations and institutional policies, protects the rights and welfare of vulnerable subjects, and enhances the reliability of research data [2] [1]. This application note provides a standardized, actionable framework for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in studies where potential subjects may lack decision-making capacity.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

A Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) is "an individual, or judicial or other body authorized under applicable law to consent on behalf of a prospective subject to the subject’s participation in the procedure(s) involved in the research" [1]. An LAR is distinct from a parent or guardian consenting for a child, as their role is specifically for adults who lack the mental capacity to provide informed consent themselves [2].

Decision-making capacity refers to a prospective subject's ability to understand the nature of the research, the consequences of participation, and the alternatives, and to make a reasoned choice. This capacity is not a global trait but is assessed in the context of the specific research protocol, with greater capacity required for higher-risk studies [1]. The pre-consent preparation phase encompasses all activities prior to the consent discussion with an LAR, including document assembly, staff training, and planning for capacity assessment.

Document Assembly and Checklist

A comprehensive document package must be assembled before approaching an LAR. The following checklist and table summarize the core and conditional elements.

Table 1: Essential Document Checklist for LAR Informed Consent

| Document Category | Specific Elements & Requirements | Applicable Regulation/Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Core Consent Form | - Concise Key Information summary at the beginning.- Statement that the study is research, its purpose, and expected duration.- Description of procedures and experimental components.- Reasonably foreseeable risks and discomforts.- Reasonably expected benefits to the subject or others.- Disclosure of alternative procedures.- Confidentiality statement regarding records.- Compensation and treatment information for research-related injuries.- Contact information for questions and research-related injuries.- Voluntary participation statement. | Revised Common Rule [27] |

| Supporting Documents | - IRB-approved protocol for staff reference.- Capacity assessment tool or guide, if applicable.- LAR identity and authority verification form.- Study information sheets or visual aids for the LAR/subject. | FDA Regulations [28] |

| Conditional Elements | - Statement on unforeseeable risks to a subject or embryo/fetus.- Circumstances for termination of participation.- Details of any payment to the subject.- Additional costs to the subject.- Consequences of withdrawal from research.- Statement on provision of significant new findings.- Approximate number of subjects in the study.- Statements on commercial profit from biospecimens and disclosure of research results. | IU HRPP Guidance [27] |

Additional conditional elements are required for specific types of research. For genetic studies, the consent must include statements about the potential for commercial profit from biospecimens and whether the subject will share in those profits, as well as information about whole genome sequencing [27]. For NIH-funded research generating large-scale genomic data, specific language regarding data sharing, de-identification, and potential risks of re-identification must be incorporated [27].

Staff Training Protocols and Competencies

Research staff involved in the LAR consent process must undergo standardized training beyond standard human subjects protection education. The training should be documented for each staff member.

Table 2: Essential Staff Training Modules and Competencies

| Training Module | Key Content | Method of Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| LAR Regulations & Hierarchy | - Definition of LAR versus guardian for a minor.- Understanding the state-specific hierarchy of LAR authority (e.g., agent under advance directive, legal guardian, spouse, adult child, parent).- Conditions limiting LAR use in your jurisdiction. | Written quiz or certification based on state law and institutional policy [1]. |

| Capacity Assessment | - Protocols for assessing a subject's decision-making capacity.- Evaluating understanding of research, consequences, and alternatives.- Differentiating between capacity for low-risk and high-risk protocols. | Observed structured clinical evaluation (OSCE) or role-playing scenarios [1]. |