Integrating Cultural Competence into the Ethical Review Process: A Framework for Researchers and IRBs

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and ethics professionals to integrate cultural competence into the ethical review process for biomedical and clinical research.

Integrating Cultural Competence into the Ethical Review Process: A Framework for Researchers and IRBs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and ethics professionals to integrate cultural competence into the ethical review process for biomedical and clinical research. It explores the ethical imperative of cultural competence, outlines practical methodologies for its application in study design and informed consent, addresses common challenges like implicit bias and communication barriers, and presents strategies for validating and evaluating these efforts. By synthesizing current standards and evidence-based practices, this guide aims to enhance the ethical quality, scientific validity, and equity of research involving diverse populations.

The Ethical Imperative: Why Cultural Competence is Non-Negotiable in Research Review

### Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the core difference between cultural competence and cultural humility?

A: Cultural competence is often viewed as a status or mastery of specific knowledge about different cultures. In contrast, cultural humility is an ongoing process-oriented approach. It is based on self-reflexivity, appreciating patients' or participants' expertise on their own lives, openness to power-balanced relationships, and a lifelong dedication to learning. While competence can risk stereotyping, humility fosters person-centered care [1].

Q: Why is an intersectional approach critical in research and evaluation?

A: Intersectionality suggests that an individual's beliefs, values, and experiences are shaped by the intersection of multiple characteristics, such as race, class, gender, and sexual orientation. An approach that focuses solely on one aspect, like race, risks essentializing the individual and discrediting their unique perspective. Using an intersectional lens prevents oversimplification and allows for a more accurate and respectful understanding of research participants [1].

Q: How can I adapt the informed-consent process for low-literacy or bilingual populations?

A: Key adaptations include simplifying consent forms, translating them into the participant's primary language, and ensuring the process is comprehensible. One project with a Mayan-speaking population in Yucatan, Mexico, provides a strong model. Researchers complied with both U.S. and Mexican regulations by providing forms in both Spanish and Mayan, and paid special attention to the participants' limited literacy and potential diminished autonomy due to age [2].

Q: What are the key components of a culturally competent informed-consent process?

A: A robust process ensures participants receive a complete and comprehensible description of the research. This includes its objectives, why they are being asked to participate, and assurance that participation is voluntary with no negative consequences for declining. Researchers must explain potential risks and benefits, protect confidentiality, and use language and concepts the participant can understand [2].

Q: My research involves a community I am not familiar with. What is the first step I should take?

A: The first step is self-reflection. Cultural competence requires a high degree of self-awareness to understand how your own background and experiences serve as assets or limitations in the evaluation [3]. Adopt a stance of cultural humility, acknowledging what you do not know and demonstrating openness to learning from the community members, who are the experts on their own lives [1].

Q: How does culture fundamentally impact the design and execution of an evaluation?

A: Culture is central to evaluation because it shapes the questions we ask, the data we deem important to collect, how we analyze it, and how we interpret the findings. Evaluations cannot be culture-free; they always reflect the culturally influenced norms and values of those who design them. A culturally competent evaluator acknowledges this and actively engages cultural dimensions to ensure validity [3].

### Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

| Scenario | Potential Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Participant seems hesitant during consent. | Process may not be fully comprehensible or may cause anxiety, especially with low-literacy populations or where official documents are viewed with suspicion [2]. | Simplify language, use verbal explanations alongside documents, and reaffirm the voluntary nature of participation. Consider oral consent if a written signature is a barrier [2]. |

| Evaluation findings seem to miss important context. | The evaluation design may reflect the researcher's cultural norms and worldviews, overlooking culturally specific impacts [3]. | Engage community stakeholders in the design phase. Practice cultural humility by appreciating the "lay expertise" of participants to shape a more relevant evaluation [1]. |

| A participant's behavior doesn't align with your expectations based on their cultural background. | Applying generalized cultural knowledge can lead to stereotyping and ignores intersectionality [1]. | Treat each person as an individual. Remember that culture is dynamic and a person's beliefs are shaped by the intersection of all their social statuses [1]. |

| Disagreement arises with community partners over methodology. | Power imbalances between researchers and communities are being replicated [1]. | Be open to sharing power with patients and community partners. A culturally humble approach involves collaboration and power-balanced relationships [1]. |

| Recruitment yields a non-diverse participant pool. | Organizational practices or researcher biases may be creating barriers for certain groups [4]. | Implement a framework of cultural competence interventions, which can include minority recruitment into research teams and developing more inclusive outreach materials [4]. |

### The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Frameworks & Components

Table: Frameworks for Cultural Competence and Humility

| Framework/Component | Description | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural Humility | An orientation based on self-reflexivity, appreciation of patients' lay expertise, and openness to sharing power [1]. | Shifts the paradigm from "mastering" cultures to lifelong learning and patient-centered care, reducing power imbalances [1]. |

| Intersectionality | A concept recognizing that an individual's experiences are shaped by the intersection of their multiple social statuses (e.g., race, class, gender) [1]. | Prevents stereotyping by ensuring individuals are not reduced to a single cultural or racial identity [1]. |

| Organizational-Level Interventions | Efforts that target the leadership and workforce of an institution [4]. | Addresses disparities by promoting diverse recruitment and institutional policies that support culturally competent practices [4]. |

| Structural-Level Interventions | Changes to the processes of care and research, such as developing interpreter services and language-appropriate materials [4]. | Removes systemic barriers to participation and ensures accessibility for diverse populations [4]. |

| Clinical/Interpersonal-Level Interventions | Training and education for providers and researchers on cross-cultural communication [4]. | Improves the quality of the direct interaction between the researcher/provider and the participant/patient [4]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. The content is framed within the broader thesis that cultural competence—the ability to honor the beliefs, customs, and values of diverse populations—is an ethical imperative grounded in the principles of respect for persons, justice, and beneficence [5]. Providing effective, equitable support requires not only technical skill but also an understanding of the diverse cultural and linguistic contexts in which our research tools are used. This ensures that our scientific work is both ethically sound and universally accessible.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Clinical Data Integration from Diverse Populations

Problem: Researchers are unable to successfully integrate or normalize clinical data collected from multinational trial sites, leading to errors in analysis.

Application to Cultural Competence: Data collection instruments (e.g., surveys, assessments) may not be culturally equivalent, leading to biased or uninterpretable data. Ethical research (justice) requires ensuring data quality and representativeness across all participant groups [5].

Methodology:

- Understand the Problem: Actively listen and ask clarifying questions to determine the exact nature of the integration error (e.g., is it missing data, formatting inconsistencies, or value mismatches?) [6].

- Isolate the Issue:

- Check if the issue is isolated to data from a specific site or region.

- Compare the data structure from the problematic source against a known, correctly integrated source.

- Review translation and cultural adaptation protocols for the original data collection tools to identify potential sources of measurement non-equivalence [5].

- Find a Fix or Workaround:

- Workaround: Implement data-cleaning scripts that account for identified cultural or regional formatting differences (e.g., date formats, numerical separators).

- Settings Update: Collaborate with site investigators to re-harmonize data collection procedures, ensuring they are culturally appropriate and technically consistent.

- Engineering Fix: Request a permanent update to the data integration platform (e.g., the Rare Disease Cures Accelerator-Data and Analytics Platform) to better handle multicultural data formats by design [7].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Access to Collaborative Research Tools

Problem: A international research team member cannot access a shared, cloud-based research platform or database.

Application to Cultural Competence: Barriers to access can inadvertently exclude collaborators based on geography, language, or institutional resources, violating the ethical principle of justice. Furthermore, support interactions must use clear, jargon-free language to be understood by team members for whom English may not be a first language [8] [5].

Methodology:

- Understand the Problem: Gather information from the user. What is the exact error message? From which country and institution are they accessing the platform? Have they successfully accessed it before?

- Isolate the Issue:

- Ask the user to verify their internet connection is stable.

- Check if the user's account permissions and credentials are correctly configured for their role and institution.

- Investigate if the user's regional internet firewall or security settings are blocking access.

- Check for potential service outages that may be specific to certain regions [9].

- Find a Fix or Workaround:

- Workaround: Guide the user to try accessing the platform through a different network or using a VPN, if compliant with security policies.

- Settings Update: Verify the user's identity and update their account permissions or assist them in resetting their password.

- Engineering Fix: If the issue is widespread for a specific region, work with IT to adjust firewall rules or deploy a regional server instance to improve access [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

| Question | Answer and Ethical Context |

|---|---|

| I am setting up a clinical trial database. What key cultural and demographic variables should I include to ensure equitable analysis? | At a minimum, you should collect standardized data on race, ethnicity, preferred language, health literacy level, and socioeconomic indicators [5]. The ethical principle of justice requires this to ensure that trial results are generalizable and that therapies are effective across subpopulations, not just the majority. |

| A translated informed consent document is not displaying correctly in our electronic system. What should I do? | First, ensure the document's file encoding supports special characters (e.g., UTF-8). Then, verify with a cultural liaison that the formatting issue has not compromised the document's readability or meaning. Respect for persons requires that participants fully comprehend consent materials in their preferred language [5]. |

| My computer is running very slowly when analyzing large genomic datasets. How can I improve performance? | Close other energy-intensive programs. Use Task Manager (Windows) or Activity Monitor (macOS) to identify applications consuming excessive CPU or memory. Ensure your operating system and analysis software are up to date. If storage is full, move data to cloud or external storage [9] [10]. Beneficence (maximizing good outcomes) is supported by maintaining efficient research tools. |

| I've accidentally deleted a critical research data file. Can it be recovered? | Yes, act quickly. First, check your Recycle Bin (Windows) or Trash (macOS). If you have a backup system like Time Machine (macOS) or File History (Windows), restore from there. If not, use file recovery software (e.g., Recuva, Disk Drill), but install it on a different drive to avoid overwriting the deleted file [9]. Protecting data is a core aspect of research integrity and beneficence. |

| I received a suspicious email asking for participant data. Is this a phishing attempt? | Almost certainly. Do not click any links or download attachments. Exercise caution with emails from unknown senders, even if they appear legitimate. Forward the email to your IT support team for verification and then delete it [9]. Upholding justice and respect requires protecting participant confidentiality from such threats. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

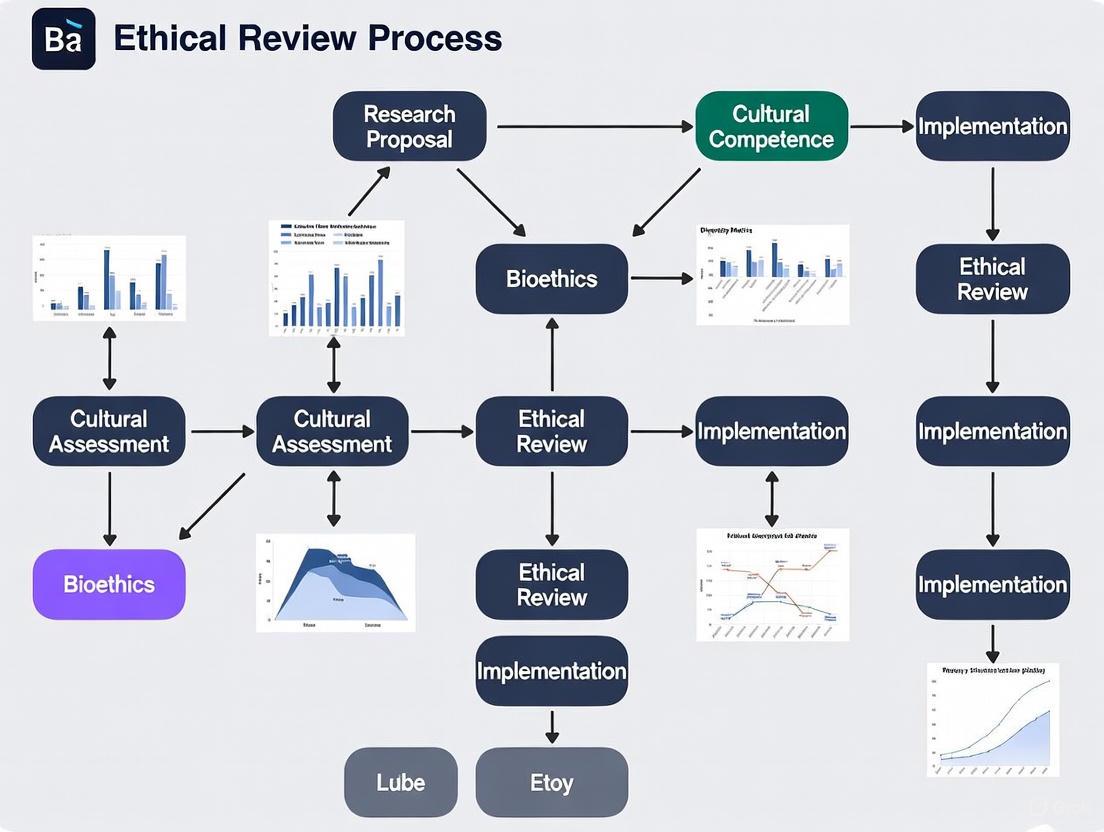

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating cultural competence into the technical and ethical review processes of a research project. This ensures the principles of respect, justice, and beneficence are operationalized at every stage.

Research Ethics and Cultural Competence Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and tools essential for conducting ethically grounded and technically sound research in culturally diverse settings.

| Item/Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Cultural Competence Frameworks (e.g., from OMS) | Provides guidelines for providing culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS), helping to ensure respect and justice in participant interactions [5]. |

| Rare Disease Cures Accelerator-Data and Analytics Platform (RDCA-DAP) | A platform that promotes the sharing and standardization of patient-level data, which is critical for ensuring research includes and benefits diverse patient populations, aligning with beneficence [7]. |

| Alzheimer's Disease Clinical Trial Simulation Tool | A quantitative tool to help optimize clinical trial design. Using such tools ethically requires ensuring the underlying data represents diverse populations to avoid biased outcomes [7]. |

| Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Consortium Measures | Provides validated assessment measures for different therapeutic areas. Their cultural validity and appropriate translation are prerequisites for ethical application (justice) [7]. |

| Remote Desktop Support Tools (e.g., screen sharing) | Allows IT support to assist researchers remotely, reducing downtime. This must be done with clear communication and consent, respecting the user's technical comfort level [8] [11]. |

| Self-Service Knowledge Base & FAQs | Empowers researchers to find solutions to common technical problems independently. Content should be clear and accessible to non-native speakers, a practice of respect [8] [11]. |

The process of informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical clinical research, founded on the principle of respecting individual autonomy [12]. However, the practical application of this principle is deeply influenced by cultural norms and values. International ethical guidelines, often rooted in Western liberal individualism, prioritize the individual's right to make autonomous choices [12]. In many other cultures, decision-making is a communal process, where family members or community leaders play a crucial role [13] [12]. This divergence can create significant challenges in multicultural research settings. For instance, a researcher strictly adhering to Western standards might insist on obtaining consent solely from an individual, potentially disrespecting cultural norms and eroding trust. Conversely, relying solely on family consent could violate the ethical principle of individual autonomy. This technical guide provides troubleshooting advice and frameworks to help researchers navigate these complex cultural landscapes, ensuring that the informed consent process is both ethically sound and culturally respectful.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common cultural barriers to obtaining genuine informed consent?

- Differing Decision-Making Models: In cultures with a communitarian perspective (e.g., influenced by Ubuntu ethics in some African communities or norms in many Asian societies), an individual may not feel empowered to make a decision without consulting the family or community head [12]. Applying a strict individualistic model can be perceived as disrespectful.

- Language and Literacy: Complex, legalistic consent forms can be a barrier, especially when translation is inadequate or when working with populations with varying literacy levels [14]. Meaningful understanding requires more than a verbatim translation.

- Power Dynamics and Trust: Historical exploitation in research, such as the cases of the Havasupai Tribe and the Pfizer Trovan study in Nigeria, has bred deep-seated mistrust in some communities [13] [12]. Potential participants may view the research process with suspicion, and power imbalances between the researcher and participant can impede a truly voluntary decision [14].

- Varied Perceptions of Risk and Benefit: Motivations for participation and perceptions of what constitutes a risk or benefit can vary culturally. Some individuals may participate out of a sense of obligation or a desire to please authority figures, while others may have concerns about how the research could impact their entire community, not just themselves [13].

Q2: How can we adapt the informed consent process for cultures with communal decision-making?

Adapting the process requires a balanced approach that honors cultural traditions while safeguarding individual rights.

- Engage the Community Early: Consult with community leaders and family members in the initial stages of research design and before approaching potential individual participants [12] [14].

- Redefine the Process: Frame the consent process as a series of conversations that involve both the individual and their trusted family members, rather than a single transaction with an individual [14].

- Seek Individual Affirmation: After discussions with the family, privately confirm the individual participant's willingness to join the study and ensure they understand they can withdraw at any time without consequence [12].

Q3: What practical tools can enhance understanding during the consent process?

- The Teach-Back Method: Ask participants to explain the study's key aspects in their own words. This confirms comprehension rather than just assuming it [14].

- Audio-Visual Aids: Use videos, diagrams, and other visual tools to convey complex information, which can be especially helpful for participants with lower literacy [14].

- Trained Interpreters: Employ professional interpreters who understand research terminology and cultural nuances, rather than relying on family members or untrained staff [14] [5].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

| Scenario | Challenge | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The Reluctant Individual | An individual seems willing but defers to family members who are hesitant or unavailable. | Pause the process. Do not pressure the individual. Schedule a follow-up meeting with key family members present to address their concerns collectively. Reframe the benefits in terms of family or community well-being. |

| Complex Protocol | The research involves a scientifically complex intervention that is difficult to explain, leading to low comprehension scores. | Simplify the language in the consent form. Utilize visual aids or flowcharts to illustrate the study design and procedures. Use the "Teach Back Method" to iteratively improve understanding. |

| Historical Mistrust | A community with a history of research exploitation is resistant to engagement and recruitment. | Prior to any research, invest time in building authentic community partnerships. Acknowledge past wrongs transparently. Involve trusted community figures, such as physicians or religious leaders, in the recruitment and consent process [15]. |

| Language Barrier | Consent forms have been translated, but participants still struggle to understand key concepts. | Move beyond written forms. Use a trained interpreter to conduct the entire consent conversation verbally. Employ audio-visual resources in the participant's primary language. Ensure all ongoing communication is also provided in their language. |

Quantitative Data on Cultural Diversity in Research

Table 1: Consequences of a Lack of Diversity in Clinical Research

| Issue | Example | Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Efficacy | Clopidogrel, a heart attack prevention drug, was found to be ineffective for 57% of British South Asians who are intermediate or poor metabolizers. | Increased risk of recurrent heart attacks in a specific population; limited drug effectiveness. | [16] |

| Diagnostic Accuracy | Race-based adjustments for estimating kidney function (eGFR) delayed diagnosis and care for Black patients. | Later-stage diagnosis, limited access to transplants, and perpetuation of health disparities. | [16] |

| Vaccine Uptake | Despite higher risks, COVID-19 vaccine uptake was significantly lower in Black (57-65%) compared to white (90%) communities in London during the first 6 months. | Confusion, hesitancy, and poorer health outcomes during a pandemic due to a lack of representative safety data and trust. | [16] |

| Oncology Trials | Less than 3% of participants in clinical trials for immune checkpoint inhibitors were Black. | Unclear if advanced cancer therapies work equally well across racial and ethnic populations. | [15] |

Table 2: Practical Strategies for Enhancing Diversity and Cultural Sensitivity

| Strategy | Key Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Build Trust via Community Physicians | Engage local doctors as sub-investigators. | Patients feel more comfortable participating with a familiar physician [15]. |

| Community Partnership | Partner with churches, advocacy groups, and local clinics for consistent outreach. | Establishes trust through culturally sensitive environments and trusted leaders [15]. |

| Staff Training | Train research staff in cultural humility, implicit bias, and communication. | Creates a respectful environment that retains diverse participants [15] [5]. |

| Reduce Logistical Barriers | Offer evening/weekend hours, combine visits, provide travel/parking information. | Enhances accessibility for working individuals and underserved populations [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Culturally Competent Research

Protocol 1: Developing Culturally Relevant Informed Consent Guidelines

This protocol is adapted from a study conducted in Lebanon, which used a Design Thinking and Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework [14].

- Objective: To collaboratively create informed consent guidelines that are culturally relevant and acceptable to both researchers and the target community.

- Methodology:

- Form a Partnership: Establish a collaborative team including researchers, community leaders, and potential participants from the affected community.

- Exploratory Phase: Conduct focus groups and in-depth interviews to explore community perceptions, barriers, and facilitators to understanding and providing informed consent. Key themes to investigate include trust-building, motivations for participation, and decision-making dynamics [14].

- Synthesis and Ideation: Analyze qualitative data to identify key themes and challenges. Collaboratively brainstorm potential solutions and components for the new consent guidelines.

- Co-Development: Draft the consent guidelines with the partnership team. Key components may include using simplified language, audio-visual aids, and structuring the process as an ongoing dialogue rather than a one-time signature [14].

- Iterative Testing and Refinement: Pilot the new guidelines with a small group from the community. Use feedback to refine and finalize the guidelines.

- Outcome Measures: Successful implementation is measured by improved participant comprehension scores, higher comfort levels reported by participants and staff, and increased recruitment and retention rates from the target community.

Protocol 2: Integrating Cultural Humility into the Consent Process

This protocol focuses on the internal stance and continuous practice of the research team [5].

- Objective: To cultivate an approach within the research team that emphasizes self-reflection and partnership, leading to more authentic and ethical consent processes.

- Methodology:

- Pre-Study Self-Reflection: Before engaging with participants, the research team should engage in structured self-reflection and implicit bias training. Team members should journal their own cultural backgrounds, assumptions, and potential biases [5].

- Community Mapping: Research and understand the demographic and social context of the community where the research will take place, including resource disparities and historical relations with research institutions [5].

- Culturally Humile Communication: During the consent process, researchers should:

- Explicitly state that the process is collaborative.

- Use open-ended questions (e.g., "What questions do you have for me?" instead of "Do you understand?").

- Ask patients about their background, practices, and preferences to avoid stereotyping.

- Inquire, "Is there anything else you would like to add to be better understood?" at the end of a session [5].

- Post-Encounter Debriefing: The team should regularly debrief after consent sessions to discuss what went well, what challenges arose, and how their own biases may have influenced the interaction.

- Outcome Measures: This is assessed through qualitative feedback from participants on their sense of being heard and respected, as well as through the research team's own reflective journals and debriefing notes.

Conceptual Framework: Navigating Cultural Influences on Informed Consent

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between cultural challenges, the principles of cultural competemility, and the resulting ethical outcomes in the informed consent process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Culturally Competent Research

This table details key conceptual "reagents" and their functions in designing and implementing ethically and culturally sound research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cultural Competence

| Research 'Reagent' | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cultural Humility | The foundational "solvent" for all interactions. It is a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and critique to redress power imbalances, fostering mutually beneficial partnerships rather than a paternalistic dynamic [17] [5]. |

| Community Advisory Board (CAB) | A "catalyst" for trust and relevance. This panel of community members provides invaluable input on study design, recruitment strategies, and consent materials, ensuring the research is acceptable and respectful to the community [13] [14]. |

| Culturally Validated Communication Tools | "Delivery vehicles" for information. These include professionally translated materials, audio-visual aids, and the "Teach Back Method." They ensure that information about risk, benefit, and procedures is not just delivered but is truly understood [14]. |

| Diversity Action Plan | The "experimental protocol" for inclusion. A formal plan required by regulators (e.g., FDA's DEPICT Act) that outlines specific goals and strategies for enrolling a participant population that reflects the demographics of the disease burden [16]. |

| Ethical Framework (e.g., Ubuntu vs. Liberalism) | The "theoretical model" for navigating dilemmas. Understanding different ethical frameworks (e.g., communitarian vs. individualistic) helps researchers anticipate conflicts and design consent processes that respect cultural values while upholding core ethical principles [12]. |

Understanding Historical Trauma and Community Mistrust in Research

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Barriers to Research Participation

Problem: Potential participants from historically marginalized groups express reluctance or refuse to enroll in research studies.

Possible Cause 1: Deep-seated mistrust of the healthcare and research system.

- Diagnosis: This mistrust often stems from knowledge of historical abuses (e.g., the Tuskegee Syphilis Study) and is reinforced by ongoing personal or community experiences with discrimination and inequitable care [18] [19].

- Solution: Acknowledge historical trauma openly. Implement transparent research practices and build long-term, equitable partnerships with communities before initiating research [18] [14].

Possible Cause 2: Concerns about exploitation and lack of benefit.

- Diagnosis: Potential participants may worry that the research findings will be used to reinforce negative stereotypes or will not benefit their community [18].

- Solution: Clearly articulate how the research will benefit the community. Involve community stakeholders in developing the research questions and plans for disseminating findings [18] [14].

Possible Cause 3: Culturally incongruent recruitment and consent processes.

- Diagnosis: Use of complex jargon, lengthy written forms, and lack of consideration for power dynamics can hinder genuine understanding and consent [14].

- Solution: Simplify communication, use the "Teach Back" method, and consider audio-visual aids. Ensure the consent process is a reciprocal dialogue rather than a formality [14].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting the Informed Consent Process

Problem: Participants sign consent forms but demonstrate limited understanding of the research protocol, their rights, or the potential risks and benefits.

Possible Cause 1: Language, literacy, and conceptual barriers.

- Diagnosis: Participant Information Leaflets/Informed Consent Forms (PIL/ICF) are often lengthy, complex, and not in the participant's primary language [14].

- Solution: Develop concise, straightforward materials in the participant's preferred language. Use trained interpreters and avoid technical jargon [14].

Possible Cause 2: Power imbalances between researchers and participants.

- Diagnosis: Participants may agree due to perceived authority of the researcher or institution, not from a place of autonomous understanding [14].

- Solution: Foster an environment of mutual trust and equality. Emphasize that participants can ask questions and withdraw at any time without penalty [14].

Possible Cause 3: Inadequate time for decision-making.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is historical trauma and how does it relate to research mistrust?

A: Historical trauma is the "emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations" resulting from massive cumulative group trauma, such as colonization, genocide, and specific events like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [19] [20]. This trauma is passed down and can manifest as a protective historical trauma response, including a compulsion to distrust the health care system, providers, and research institutions [19]. Mistrust is therefore not an individual character flaw but a rational response to a history of exploitation and broken trust [18] [19].

Q2: Beyond Tuskegee, what are other historical events contributing to this mistrust?

A: While the Tuskegee Syphilis Study is a sentinel event, the history of medical and research abuse of African Americans is extensive [18]. Harriet Washington's work documents this long history of exploitation [18]. More recent examples include a 1990s study where a prestigious university recruited African American boys to test a genetic etiology for aggression, which involved withdrawing medications and administering a drug with potential risks [18]. For First Nations peoples in Canada, the residential school system is a primary source of historical trauma, where children were forced to assimilate and suffered abuse, the effects of which are intergenerational [20].

Q3: How can we build trust with communities that have experienced historical trauma?

A: Trust-building requires a long-term, committed approach [14]:

- Community Partnership: Engage community leaders and members as equal partners from the very beginning of research conceptualization, not just for recruitment [14] [20].

- Cultural Humility: Practice cultural humility, which is a lifelong process of self-reflection to acknowledge one's own cultural biases and build equitable relationships [21].

- Transparency and Accountability: Be transparent about the research goals, methods, and potential outcomes. Report back results to the community in an accessible way [18].

- Sustainable Benefit: Ensure the research provides a direct, tangible benefit to the community and does not merely extract data [14].

Q4: Our Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol is approved. Why do we still face mistrust?

A: An IRB approval is a necessary baseline for ethical research, but it is not sufficient to overcome deep-seated historical and personal mistrust [19]. Regulatory compliance focuses on protecting institutions, while building trust is a relational process that focuses on the community [14]. Earning trust requires going beyond the mandatory IRB requirements to implement the culturally competent and humble practices described in these guides [21].

Experimental Protocols & Data

This table summarizes qualitative data from a study exploring barriers to research participation among African American adults (N=70 across 11 focus groups) [18].

| Theme | Frequency of Mention | Key Illustrative Quotes | Participant Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mistrust of Healthcare System | High; expressed across all groups | "They are not being truthful... they are not telling you everything." | All participants, regardless of prior research experience or SES [18] |

| Historical Exploitation | High | References to Tuskegee and other events | Across all groups [18] |

| Fear of Experimentation | Moderate | Concerns about being "guinea pigs" | Participants without prior research experience [18] |

| Lack of Cultural Diversity | Moderate | Perception of differential treatment compared to Whites | Across all groups [18] |

Protocol 1: Conducting Culturally Grounded Qualitative Research

Aim: To gain an in-depth understanding of community-specific barriers and facilitators to research participation [18] [20].

Methodology:

- Design: Use a grounded theory design, where theory emerges from the data without preconceived hypotheses. Combine with Participatory Action Research (PAR) to actively engage the community in solving problems [18] [14].

- Sampling: Employ a purposive sampling strategy to identify adults from the community, ensuring representation across gender, age, and socioeconomic status. Include individuals with and without previous research experience [18].

- Data Collection: Conduct focus groups in a comfortable, informal atmosphere. Use a conversational moderator guide with introductory, key, and ending questions. Audio-record sessions and have a co-moderator take notes on group dynamics and non-verbal cues [18].

- Data Analysis: Transcribe recordings. Use a whole-text analysis and open-coding method to identify themes. Establish inter-rater reliability among coders. Use qualitative software to manage data. Identify significant themes based on frequency, passion, and use of illustrative stories [18].

- Ethical Considerations: Obtain informed consent approved by a relevant ethics committee. Debrief moderators after each session. Compensate participants for their time [18].

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Trust-Building Research Workflow

Diagram 2: Historical Trauma Impact Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Community Advisory Board (CAB) | A group of community stakeholders that provides ongoing guidance, ensures cultural relevance, and helps build trust between researchers and the community. |

| Culturally Adapted Consent Tools | Simplified guides, audio-visual materials, and translated documents that make the informed consent process genuinely accessible and understandable. |

| Trained Cultural Brokers/Interpreters | Individuals who can bridge cultural and linguistic gaps between the research team and participants, ensuring clear communication and mutual understanding. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., QSR N6) | Software used to systematically code, manage, and analyze qualitative data from focus groups and interviews to identify key themes [18]. |

| Partnership Agreements (MOU) | Formal Memoranda of Understanding that outline the roles, responsibilities, and data sharing agreements between the research institution and community partners. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Ethical Review Challenges in Culturally Diverse Research

Problem: Research protocols are delayed because the informed consent process is not adequate for populations with low literacy or limited English proficiency.

Solution: Implement a culturally competent informed consent process.

- Step 1: Assess Participant Needs. Before protocol submission, identify the specific communication needs of your target population, including primary language, literacy level, and common cultural beliefs about research [2].

- Step 2: Adapt Consent Materials. Simplify forms for low literacy and translate them into the participant's primary language. Ensure translations are culturally appropriate, not just literal [2].

- Step 3: Implement Verbal Explanation. Use trained interpreters or bilingual staff to explain the research project verbally. Allow ample time for questions and discussion, ensuring comprehension beyond a signed form [2].

- Step 4: Verify Understanding. Use "teach-back" methods where participants explain the study in their own words to confirm true informed consent [2].

- Step 5: Document the Process. For IRB compliance, document the steps taken to ensure understanding, which may include audio recording of oral consent in lieu of a written signature if approved by the IRB [2].

Preventive Measures: Consult with cultural or community leaders during the study design phase to proactively address potential barriers to consent.

Guide 2: Addressing Cultural Competence Gaps in Research Teams

Problem: The research team lacks the cultural awareness to effectively engage with a study population, leading to low recruitment or poor data quality.

Solution: Integrate NASW's cultural competence standards into team training and protocol development.

- Step 1: Conduct a Self-Assessment. Team members should engage in self-awareness activities to understand their own cultural identities, privileges, and potential biases, as outlined in NASW Standard 2 [22].

- Step 2: Acquire Cross-Cultural Knowledge. Develop specialized knowledge about the history, traditions, values, and family systems of the population you are studying, in line with NASW Standard 3 [22].

- Step 3: Apply Cross-Cultural Skills. Use communication and engagement skills that demonstrate respect for the population's culture. This includes using appropriate non-verbal cues and addressing cultural norms in interactions (NASW Standard 4) [22].

- Step 4: Practice Empowerment and Advocacy. Ensure the research design and implementation empower the community. Share findings with participants and advocate for services that address identified gaps, reflecting NASW Standard 6 [22].

Preventive Measures: Include a cultural competence lead on the research team and budget for ongoing training and consultation with cultural experts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key federal regulatory milestones for an Investigational New Drug (IND) application?

A: The IND process is a critical federal regulatory pathway. The following table summarizes the key phases and requirements [23]:

Table 1: Key Milestones in the Investigational New Drug (IND) Application Process

| Phase | Primary Objective | Typical Sample Size | Data Required to Proceed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical | To determine if the product is reasonably safe for initial human use and exhibits pharmacological activity that justifies commercial development [23]. | N/A (Animal studies) | Data on toxic and pharmacologic effects through in vitro and in vivo laboratory animal testing [23]. |

| Phase 1 | Initial introduction into humans to determine metabolic and pharmacological actions, side effects, and early evidence on effectiveness [23]. | 20-80 subjects [23] | Successful preclinical data and FDA authorization (30 days after IND submission if not contacted by FDA) [23]. |

| Phase 2 | To obtain preliminary data on the effectiveness of the drug for a particular indication and to determine common short-term side effects and risks [23]. | Several hundred patients [23] | Safety and pharmacological data from Phase 1 trials. |

| Phase 3 | To gather additional information about effectiveness and safety to evaluate the overall benefit-risk relationship and provide an adequate basis for physician labeling [23]. | Several hundred to several thousand people [23] | Promising evidence of efficacy and acceptable safety from Phase 2 trials. |

Q2: When is an IND required for clinical investigation?

A: An IND is required if you are conducting a clinical investigation with an investigational new drug. However, an IND may not be required for the clinical investigation of a marketed drug if all these conditions are met [23]:

- The investigation is not intended to support a new indication or significant labeling change.

- It does not involve a route of administration or dosage level that increases risks.

- It is conducted in compliance with IRB review and informed consent regulations (21 CFR parts 56 and 50).

- It does not intend to invoke exception from informed consent requirements (21 CFR 50.24) [23].

Q3: How do I properly cite the NASW Code of Ethics in APA style?

A: Proper citation is crucial for academic and professional integrity. Use the following format [24]:

- Reference List Entry: National Association of Social Workers. (2021). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

- In-text Citation (Parenthetical): (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2021)

- In-text Citation (Narrative): National Association of Social Workers (NASW, 2021)

- Citing a Specific Section: (NASW, 2021, Standard 1.05)

Q4: What is the role of an Institutional Review Board (IRB) in protecting culturally diverse populations?

A: The IRB is formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research to ensure the rights and welfare of human subjects. This is especially critical for marginalized populations. An IRB must have at least five members with varying backgrounds to provide a complete and adequate review of research protocols, ensuring they are culturally acceptable and minimize coercion. IRBs are required for FDA-regulated research, even when subjects are not institutionalized [23].

Q5: Where can researchers find training on cultural competency?

A: Free, accredited e-learning programs are available. For example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services offers a course called "Improving Cultural Competency for Behavioral Health Professionals." This training covers self-awareness, understanding a client's cultural background, and building stronger therapeutic relationships, which is directly applicable to researcher-participant dynamics [25].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Ethical Review Process with Integrated Cultural Competence

This protocol details a methodology for integrating cultural competence into the ethical review of research involving human subjects, framed within a binational research context [2].

- Objective: To ensure that the ethical review process adequately protects the rights and welfare of participants from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

- Materials:

- Research protocol document

- Draft informed consent forms (ICFs)

- Access to cultural and linguistic experts

- IRB submission forms

- Methodology:

- Pre-Submission Cultural Review: Submit the research protocol and draft ICFs for review by a panel of cultural experts or community representatives from the target population.

- Adaptation of Materials: Based on feedback, simplify and translate the ICFs. Develop verbal scripts for explaining the study to ensure consistency across participants with low literacy [2].

- IRB Submission: Submit the adapted materials, along with a detailed description of the culturally competent consent process (e.g., use of verbal consent, teach-back method), to the IRB for approval [23] [2].

- Investigator Training: Train all research staff on the specific cultural considerations of the population, including communication styles, cultural humility, and the approved consent process [22] [25].

- Process Documentation: During the study, meticulously document the consent process for each participant, noting how verbal explanations were provided and understanding was verified [2].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow:

Protocol 2: Framework for Applying NASW Cultural Standards in Research Design

This protocol provides a framework for applying the NASW Standards for Cultural Competence directly to the research design process [22].

- Objective: To embed the principles of cultural competence at every stage of research development, from conceptualization to dissemination.

- Materials:

- NASW Standards and Indicators for Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice [22].

- Research design documents.

- Methodology:

- Ethics and Values (Standard 1): Frame the research question and methodology to align with social work values of social justice, dignity, and worth of the person. Ensure the research aims to empower, not merely observe, the community [22].

- Self-Awareness (Standard 2): The research team engages in structured self-assessment activities to identify and mitigate personal and professional biases that could influence the research [22].

- Cross-Cultural Knowledge (Standard 3): Conduct a thorough literature review and engage with community stakeholders to build a foundational understanding of the cultural group's history, traditions, and social systems [22].

- Empowerment and Advocacy (Standard 6): Design the research methodology to include community participation (e.g., Community-Based Participatory Research) and plan for the dissemination of results back to the community in an accessible format [22].

- Leadership (Standard 10): Position the research project as a change agent by using findings to challenge structural oppression and advocate for policy changes that benefit the population studied [22].

The conceptual relationship between these standards and the research lifecycle is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key conceptual "reagents" – the frameworks and guidelines essential for conducting ethically and culturally competent research.

Table 2: Essential Frameworks and Guidelines for Culturally Competent Ethical Research

| Item Name | Function/Application in Research | Source/Access |

|---|---|---|

| NASW Code of Ethics | Serves as the primary ethical framework, guiding decision-making in situations involving confidentiality, informed consent, professional boundaries, and social justice. The 2021 update includes explicit guidance on cultural competence and technology use [26]. | NASW Website [26] |

| NASW Standards for Cultural Competence | Provides 10 specific standards with indicators to guide the implementation of culturally competent practice. Critical for designing research protocols that are respectful and effective with diverse populations (e.g., Standards on Self-Awareness, Cross-Cultural Skills, and Empowerment) [22]. | NASW Website [22] |

| FDA IND Regulations | Provides the legal and regulatory requirements for conducting clinical investigations of new drugs. Understanding these is mandatory for research in drug development to ensure participant safety and data integrity [23]. | FDA Website [23] |

| HHS Cultural Competency Training | Provides free, accredited training modules for professionals to increase their cultural and linguistic competency. Useful for certifying and improving the cultural awareness of research staff [25]. | Think Cultural Health HHS Website [25] |

| IRB Guidebook | Outlines the policies and procedures for the protection of human subjects. Serves as a manual for navigating the ethical review process, including special considerations for vulnerable populations [23]. | Institutional IRB / OHRP Website |

A Practical Framework: Operationalizing Cultural Competence in Study Protocols and IRB Deliberations

Conducting a Cultural Context Assessment for Your Research Population

Troubleshooting Guides

How do I initiate a cultural context assessment when starting research with a new population?

Begin by conducting a thorough preparatory review to understand the community's historical, social, and political background. This involves gathering information about shared values, beliefs, and practices that may influence research participation and outcomes [27] [28].

Key Steps:

- Review Existing Literature: Examine published research about the community and consult with cultural experts or community leaders to gain foundational knowledge [29].

- Engage Stakeholders: Identify and involve key community representatives, leaders, and potential participants early in the planning process. This fosters trust and ensures diverse perspectives are considered [29] [27].

- Develop a Structured Plan: Create a detailed assessment plan outlining methods, timelines, and required resources. Anticipate potential barriers such as language differences or cultural sensitivities to mitigate challenges later [27].

What are the most effective methods for gathering meaningful cultural data?

A mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative and qualitative techniques provides the most comprehensive view of the cultural landscape [27].

Recommended Methodologies:

- Focus Groups & Interviews: Facilitate open dialogue to gain deep insight into cultural values, perceptions, and experiences. These methods reveal nuances that surveys might miss [30] [27].

- Surveys: Use questionnaires to gather broad, quantitative data on participant attitudes, experiences, and cultural phenomena from a larger sample [31] [27].

- Observational Techniques: Provide real-time insight into workplace or community dynamics and interpersonal relationships [27].

- Collaborative Workshops: Foster an exchange of ideas and bring different community perspectives together to ensure a comprehensive understanding [27].

How can I ensure the ethical principle of informed consent is respected in diverse cultural contexts?

Standard consent procedures may not be effective across all cultures. It is crucial to adapt the process to be culturally relevant and accessible [14] [28].

Common Challenges and Solutions:

- Challenge: Language, literacy barriers, and complex consent forms hinder genuine understanding.

- Solution: Collaborate with trained interpreters and involve community members in translating materials. Simplify language in consent forms and use audio-visual methods to enhance comprehension. Employ the "Teach Back Method," where participants explain the information back to you, to confirm understanding [14].

- Challenge: Power dynamics between researchers and participants can undermine voluntary consent.

- Challenge: In societies where oral traditions are valued, written consent may be ineffective or distrustful.

- Solution: Where appropriate and ethically approved, consider oral consent processes that are documented via audio recording or a witnessed verbal agreement, rather than relying solely on written forms [14].

What should I do if my research team lacks cultural or linguistic expertise?

A lack of internal expertise is a common hurdle that can be overcome through strategic partnerships and resources.

- Engage Bicultural Researchers or Cultural Consultants: Include team members who share the cultural background of the population or hire expert consultants. They can provide critical insight into cultural norms and help navigate the research context [28].

- Utilize Trained Interpreters: Work with professional interpreters who are trained in research ethics and terminology, not just casual bilingual speakers. This ensures accurate translation and cultural mediation [28].

- Invest in Team Training: Provide cultural competence training for your research team. This should focus on developing self-awareness of one's own biases, knowledge about the specific cultural dimensions, and skills for appropriate engagement [31] [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is a cultural context assessment critical for the ethical review of my research?

Cultural context is vital because all behaviors are learned and displayed within a cultural framework. An assessment ensures that your research practices are respectful, relevant, and do not unintentionally pathologize culturally normative behaviors [32] [30]. It directly impacts core ethical principles by ensuring genuine informed consent, minimizing exploitation, and building trust with communities that may have historical reasons for distrusting research [29] [14] [28].

How does culture specifically influence the informed consent process?

Culture shapes communication styles, including norms for directness, indirectness, and the importance of nonverbal cues [32]. For instance, expectations of what constitutes a "good listener" during a consent conversation—such as maintaining direct eye contact versus allowing respectful silence—vary significantly across cultures and influence perceived responsiveness and trust [32]. Furthermore, concepts like individual autonomy, which is central to Western consent models, may be viewed differently in collectivist cultures, where family or community decision-making might be the norm [32] [28].

Are there specific populations that require special consideration?

Yes, certain groups are recognized as needing special protection and tailored approaches throughout all research phases due to vulnerability or unique lifestyles. Key populations include [33]:

- Indigenous peoples

- Quilombola communities and other traditional peoples

- People deprived of liberty

- Children and adolescents

- Pregnant and lactating women

- People with disabilities that affect decision-making

Research with these populations often requires a more intensive, culture-centered approach that harnesses community-based knowledge and practices [29].

What are the key components of a cultural assessment framework?

A comprehensive framework should integrate several core competencies. The following table summarizes the key components based on established models [31]:

| Component | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural Competence | Ability to acknowledge, respect, and respond effectively to diverse cultural backgrounds [31]. | Cultural awareness, cross-cultural communication, harnessing community knowledge [31] [29]. |

| Ethical Competence | Upholding moral principles (accountability, transparency, integrity) in decision-making [31]. | Navigating differing cultural interpretations of ethical values like honesty and equity [31]. |

| Transnational Competence | Skills to effectively navigate diverse national, cultural, and institutional contexts [31]. | Analytical skills to interpret international events, adaptability, and self-awareness [31]. |

How can I visually plan and track the cultural assessment process?

The following workflow outlines the key stages of a cultural context assessment, from preparation to implementation.

How do cultural competencies integrate into the ethical review framework?

Cultural competencies are not standalone; they must be woven into the core of your research ethics framework. The diagram below illustrates how these elements interact to support ethical research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Cultural Assessment

The following table details key methodological "reagents" essential for conducting a robust cultural context assessment.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) | A collaborative approach that equitably involves community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process [29]. This co-creation improves intervention efficacy and sustainability by integrating Indigenous-based theories and knowledge systems [29]. |

| Design Thinking (DT) & Participatory Action Research (PAR) | A combined framework that uses empathetic, user-centered design (DT) to explore problems and solutions, strengthened by the collaborative, social-change focus of PAR. This is highly effective for developing culturally relevant guidelines, such as for informed consent [14]. |

| Therapeutic Assessment (TA) Model | A semistructured, collaborative assessment intervention model from psychology. Its core values of collaboration, humility, and curiosity make it culturally responsive. It allows clinicians to tailor steps and content to the client's unique cultural background [30]. |

| Cultural Adaptation & Grounding | The process of systematically changing an evidence-based intervention to be compatible with a client's cultural values, meaning, and language. "Cultural grounding" places the cultural context at the very core of the intervention, which is advocated over more superficial adaptations for Indigenous populations [29] [30]. |

| Composite Theoretical Framework | A research framework that combines multiple theories (e.g., Cultural Relativism, Ethical Climate Theory, Transnationalism) to avoid oversimplifying the complex interplay of cultural backgrounds, experiences, and ethical decision-making in multicultural settings [31]. |

Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Informed Consent Processes

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides practical solutions for researchers facing challenges in obtaining genuine informed consent from diverse populations. The following guides address common operational hurdles, framed within the broader thesis that cultural competence is not an add-on but a fundamental component of rigorous and ethical research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Consent Barriers and Solutions

| Problem | Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Comprehension & High Illiteracy | Use of complex medical jargon; mismatch between patient health literacy and consent form language. | - Use plain language.- Implement the "Teach Back" method.- Employ interactive media and graphical tools. [34] | [34] |

| Language Barriers | Inadequate use of professional interpreters; reliance on family members or untrained staff. | - Use certified medical interpreter services for all non-proficient patients.- Ensure ASL interpreters are available for hearing-impaired patients. [34] | [34] |

| Cultural Distrust & Power Imbalances | Historical exploitation of marginalized communities in research (e.g., Tuskegee Study); perceived authority of clinicians. | - Build long-term, sustained relationships with communities.- Engage community leaders and trusted physicians.- Acknowledge historical contexts and emphasize transparency. [35] [15] [13] | [35] [15] [13] |

| Individual vs. Collective Decision-Making | Western standards prioritize individual autonomy, while many cultures use collective or family-based decision-making. | - Embrace relational approaches.- Involve family or community representatives in the consent process as appropriate.- Allow for collective discussion. [35] [34] | [35] [34] |

| Inadequate Documentation & Process Rushing | Consent obtained in high-stress settings (e.g., pre-op); time pressures on clinicians. | - Conduct consent discussions in a calm, office setting.- Allow patients time for reflection.- Ensure all key elements (risks, benefits, alternatives) are thoroughly documented. [34] | [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical steps to improve understanding during the consent process for participants with low literacy?

A: Focus on a process-based approach rather than a form-based one.

- Use the "Teach Back" method: Ask participants to explain the study back to you in their own words to confirm understanding. [34]

- Simplify language: Replace medical jargon with plain, everyday terms.

- Utilize visual aids: Employ graphics, charts, or short videos to convey complex information about risks and procedures. [14] [34]

Q2: How can we build trust with Indigenous or other communities that have historically been harmed by research?

A: Trust is built through respect for community sovereignty and sustained engagement.

- Community-Driven Processes: Engage communities in the research design and the development of the consent process itself. This is a form of decolonizing research. [35] [14]

- Use "Wise Practices": These include land-based consenting, involving Elders and knowledge holders in decision-making, and recognizing that consent for an individual cannot be isolated from their family and community. [35]

- Transparency and Benefit: Be clear about how the research will benefit the community and commit to sharing the results in an accessible format. [15]

Q3: We are required to get a signed form, but in some cultures, written consent is viewed with mistrust. What should we do?

A: A culturally competent approach respects local customs while upholding ethical standards.

- Flexible Documentation: Explore alternative documentation methods approved by your IRB/REB. This could include oral consent witnessed by a community leader and audio-recorded, or a thumbprint accompanied by a signature from a trusted witness. [14]

- Explain the Purpose: Clearly explain that the form is for the participant's protection, to ensure they have received all the information and that their agreement is voluntary.

Q4: What is the difference between cultural competence and cultural humility, and why does it matter for consent?

A: This distinction is central to moving beyond a checklist mentality.

- Cultural Competence is the product—the skill of understanding and applying knowledge about a cultural group. [5]

- Cultural Humility is the process—a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, recognizing one's own implicit biases and the power imbalances in the client-professional relationship. [5]

- Why it matters: The merging of the two, termed "competemility," allows a researcher to use cultural knowledge while remaining open-minded and other-oriented, ensuring each participant is treated as a unique individual. [5]

Quantitative Data on Consent Challenges

The following data, synthesized from the literature, highlights specific challenges in the informed consent process.

Table: Documented Deficiencies in Informed Consent Forms and Processes

| Deficiency | Quantitative Finding | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Consent Forms | Only 26.4% of consent forms were documented to include all four required elements: nature of the procedure, risks, benefits, and alternatives. [34] | Bottrell et al. (as cited in StatPearls) [34] |

| Underrepresentation in Oncology Trials | Less than 3% of participants in clinical trials for immune checkpoint inhibitors were Black, despite higher cancer mortality rates in this population. [15] | Unger et al., 2020 [15] |

| General Underrepresentation | Black and Hispanic populations frequently account for less than 10% of participants in clinical trials. [36] | WCG Clinical Insights [36] |

Experimental Protocols for Improving Consent

Here are detailed methodologies for implementing two key evidence-based strategies.

Protocol 1: Implementing the Teach-Back Method

Objective: To ensure and verify participant comprehension of the informed consent information.

Materials: Simplified consent document, visual aids (if any).

Procedure:

- Explain: Present one key concept or section of the consent form to the participant using plain language.

- Ask: Instead of asking "Do you understand?", use an open-ended question like, "I want to make sure I explained this clearly. Could you please tell me back in your own words what this means?"

- Clarify: If the participant explains the concept correctly, move on to the next section. If there is a misunderstanding or omission, re-explain the information using a different approach. Avoid blaming the participant (e.g., say "I didn't explain that well enough").

- Repeat: Continue this process for all critical elements of the consent: procedures, risks, benefits, alternatives, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw.

- Document: Note in the research record that the Teach-Back method was used to confirm understanding. [34]

Protocol 2: Developing Community-Driven Consent Guidelines

Objective: To co-create culturally relevant informed consent guidelines with the target population.

Materials: Meeting space, recording equipment, facilitators trained in cultural humility.

Procedure (Based on the Lebanon Study using Design Thinking and PAR): [14]

- Empathize and Define: Conduct focus groups and interviews with community members and researchers to explore barriers, facilitators, and perceptions of consent. Identify specific points of friction (e.g., distrust, language, power dynamics).

- Ideate: Hold collaborative workshops with community members, researchers, and local leaders. Brainstorm solutions to the identified problems. Ideas from such sessions have included using audio-visual methods, involving trusted community interpreters, and ensuring timing and setting are convenient. [14]

- Prototype: Draft a guideline for the consent process that incorporates the brainstormed solutions. This may include scripts for researchers, templates for visual aids, and protocols for community engagement.

- Test: Pilot the new consent guideline in a small-scale study. Observe the process and gather feedback from both participants and researchers.

- Implement and Refine: Finalize the guideline based on feedback and implement it in broader research, with a commitment to ongoing refinement.

Visualizing a Relational Consent Process

The following diagram illustrates a community-engaged consent model, contrasting with a traditional, linear approach. This responds to evidence that effective consent with Indigenous and other collectivist cultures requires honoring relational networks. [35]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential "reagents" or tools for implementing culturally and linguistically appropriate informed consent processes.

Table: Essential Tools for Culturally Competent Consent

| Tool / Solution | Function in the "Experiment" | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Professional Medical Interpreter | Facilitates accurate, unbiased communication between researcher and participant. | Certified, trained in research terminology and ethics; not a family member. [34] |

| Plain Language Consent Form | Serves as the baseline document for explaining the study. | Written at a 6th-8th grade reading level; uses short sentences and active voice; avoids medical jargon. [34] |

| Visual Aids & Multimedia | Acts as an adjunct to text to improve comprehension of complex procedures, risks, and benefits. | Culturally relevant imagery; simple diagrams; short, focused videos in the participant's primary language. [14] |

| Community Advisory Board (CAB) | Functions as a catalyst for trust and cultural relevance, guiding study design and consent process. | Comprised of respected community members, potential participants, and local leaders. [35] [15] |

| Cultural Humility Training | The buffer solution that prepares the research team to engage effectively and respectfully. | Focuses on self-reflection, recognizing implicit bias, and understanding power dynamics. [5] |

Developing Inclusive Recruitment and Retention Strategies

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing High Attrition in Research Teams

Problem: Research team members, particularly from underrepresented groups, are leaving within the first year.

Diagnostic Questions:

- What is the first-year attrition rate, and does it differ between demographic groups? [37]

- Do exit interviews indicate issues with culture, inclusion, or alignment with values? [38]

- Is there a perceived lack of fairness or equity in organizational processes? [39]

Solutions:

- Implement Stay Interviews: Proactively ask team members about their engagement, challenges, and what would make them stay.

- Audit and Adjust Onboarding: A robust onboarding process can boost new hire retention by up to 82%. Ensure it includes mentorship, clear objectives, and integration into the team culture. [38]

- Reinforce Inclusive Culture: Employees are three times more likely to stay when they perceive organizational processes as fair. Foster accountability for diversity goals and support practices like mentorship programs and flexible work arrangements. [39]

Guide: Overcoming a Non-Diverse Candidate Pipeline

Problem: Your recruitment process is not attracting a diverse pool of qualified applicants.

Diagnostic Questions:

- Are you using the same sourcing channels repeatedly? [37]

- Does your job description use inclusive language and focus on essential skills? [40] [41]

- Are degree requirements necessary for the role, or are they excluding skilled candidates? [42]

Solutions:

- Widen Sourcing Channels: Move beyond traditional channels. Use diverse job boards, partner with professional organizations for underrepresented groups, and leverage employee resource groups for outreach. [40]

- Revise Job Descriptions: Use tools like Textio or Gender Decoder to identify and remove biased language. Focus on essential skills and competencies rather than a long list of nice-to-have qualifications. [41]

- Eliminate Unnecessary Degree Requirements: 27% of organizations have eliminated degree requirements for certain roles, and 76% of those have successfully hired candidates who would have previously been disqualified. Conduct a job analysis to ensure requirements are based on necessary skills, not credentials. [42]

Guide: Ensuring Ethical and Culturally Competent Informed Consent

Problem: Research participants from diverse cultural backgrounds may not fully understand or feel comfortable with the informed consent process.

Diagnostic Questions:

- Are consent forms overly lengthy, complex, or reliant on Western-centric concepts? [31] [14]

- Does the process account for varying cultural norms, language barriers, and power dynamics between researcher and participant? [14]

- Are you using a "one-size-fits-all" approach to consent? [14]

Solutions:

- Adopt a "Reciprocal Dialogue": Move beyond a transactional signing of a form. Build mutual trust and allow for ongoing questions and dialogue throughout the research engagement. [14]

- Use Culturally Relevant Materials: Employ multimedia resources (videos, websites) and the "Teach Back Method," where participants explain the information back to you, to ensure comprehension. Develop guidelines that are co-created with the communities involved. [14]

- Involve Trained Interpreters: Address language and literacy barriers by using trained interpreters, not family members, to ensure accurate communication and mitigate power imbalances. [14]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the most effective strategies for attracting top talent in today's market? A: The most effective strategies are candidate-centric. Research shows that offering flexible work arrangements (61%) and improving compensation (61%) are top. Streamlining the application process (49%) and including pay ranges in job postings (48%) are also highly effective. [42]

Q: How can we reduce unconscious bias in our hiring process? A: Several strategies can help:

- Use Skills-Based Assessments: Tools like Vervoe use AI to score candidates based on performance in role-specific tasks, shifting focus from background to proven abilities. [41]

- Implement Structured Interviews: Ask all candidates the same set of questions to allow for fairer comparison. [41]

- Provide Bias Awareness Training: Training hiring teams on unconscious bias, especially using immersive methods, can improve hiring diversity. One study showed a 25% improvement in diversity over two years. [41]

- Create Diverse Interview Panels: This ensures a wider range of perspectives are considered during candidate evaluation and signals inclusivity. [41]

Q: What is the business case for investing in inclusive hiring and retention? A: Inclusive hiring is a business imperative, not just a moral one. Diverse teams are 35% more productive and creative, and inclusive organizations are 36% more profitable. They also see improved decision-making, better customer connection, and higher employee engagement. [40] [41]

Q: Our retention rates are low. What is the most impactful place to start? A: Start by hiring for cultural fit. Research indicates that 58% of employees would consider leaving for a company with a better culture. Ensuring new hires align with your organization's core values and mission fosters a sense of belonging and commitment from the start. [38]

Q: How can we make our research team's digital tools and career sites more inclusive? A: Ensure your digital presence follows Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) [43] [41]:

- Navigation: Use clear headers for screen readers.

- Color Palette: Ensure strong color contrast for visually impaired users.

- Video Captions: Provide transcripts and captions for all video content.

- Keyboard Accessibility: Ensure the site is fully navigable without a mouse. [41]

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Recruitment Metrics for Tracking Inclusivity

| Metric | Description | Target/Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| First-Year Attrition [37] | Tracks new hires who leave within the first year, indicating poor fit or unmet expectations. | Monitor for disparities between demographic groups. |

| Adverse Impact [37] | Analyzes if hiring rates for any protected group are significantly less than the group with the highest hiring rate. | A ratio of less than 0.8 may indicate discrimination. |

| Source of Hire [37] | Identifies which channels (job boards, referrals, social media) bring in successful, diverse candidates. | Double down on channels that deliver diverse, qualified candidates. |

| Selection Ratio [37] | The number of hired candidates divided by the total number of candidates. | A very low ratio can indicate overly restrictive criteria. |

| Time to Hire [37] | Days from a candidate's application to offer acceptance. A long process can cause you to lose top talent. | Aim for efficiency; global averages vary by field (e.g., 21 days for customer service, 29 for engineering). |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Diversity and Inclusion Strategies

| Strategy | Quantitative Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Accountability for D&I Goals | Employees are 2x as likely to stay. | [39] |

| Perceived Fairness | Employees are 3x as likely to stay. | [39] |

| Diverse Team Performance | Can outperform non-diverse teams by ~35% in productivity and creativity. | [40] |

| Inclusive Organizations | Are 36% more profitable than less diverse competitors. | [41] |

| Effective Onboarding | Can boost new hire retention by up to 82%. | [38] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Conducting a Pay Equity Audit

Objective: To identify and rectify unjustified pay disparities based on gender, ethnicity, or other protected characteristics.

Methodology: