Ghost Authorship and Authorship Disputes: A 2025 Guide for Ethical Research and Drug Development

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for navigating the complex landscape of authorship.

Ghost Authorship and Authorship Disputes: A 2025 Guide for Ethical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for navigating the complex landscape of authorship. It covers the foundational definitions of ghost, guest, and gift authorship, explores proven methodological tools like the ICMJE criteria and CRediT for ethical attribution, offers practical strategies for resolving and preventing disputes, and outlines validation techniques to ensure compliance with the latest 2025 journal and institutional policies. The article synthesizes current best practices to uphold research integrity, protect careers, and maintain trust in scientific publication.

Understanding Authorship Misconduct: Definitions, Prevalence, and Impact on Scientific Integrity

Your Troubleshooting Guide to Unethical Authorship Practices

This guide helps researchers identify and avoid unethical authorship practices—ghost, gift, and guest authorship—that can undermine research integrity and lead to disputes.

Quick Definitions

| Practice | Core Issue | Common Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| Ghost Authorship [1] | A person who made a substantial contribution is omitted from the author list. | A professional medical writer employed by a pharmaceutical company drafts a manuscript but is not listed as an author or acknowledged [2]. |

| Gift Authorship [1] [3] | An individual who does not qualify for authorship is credited as a author. | A junior researcher lists their department head as an author as a gesture of gratitude for general supervision or to boost the manuscript's credibility, even though the head had no direct involvement in the research [1]. |

| Guest Authorship [1] [3] | An influential individual is listed to boost the credibility of the study, despite a lack of substantial contribution. | A well-known professor is added to the author list to increase the perceived status of the publication and improve its chances of acceptance in a high-impact journal [1] [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the core ethical problem with each practice?

The table below summarizes the primary ethical breaches and consequences for each practice [1] [2] [4].

| Practice | Ethical Problem | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Ghost Authorship | • Deceives the research community about the true contributors.• Obscures conflicts of interest (e.g., industry involvement).• Withholds credit from those who deserve it. | • Misleads readers about the validity and credibility of research.• Can negatively affect patient care if biased data is presented as independent.• Violates accountability standards. |

| Gift & Guest Authorship | • Misrepresents the actual intellectual contributions to the work.• Dilutes the meaning of authorship and credit.• Unfairly skews academic credit and citation metrics. | • Makes it difficult to determine accountability for the research.• Can implicate non-contributors in cases of misconduct.• Damens the professional reputation of those involved. |

How can I distinguish between a legitimate co-author and a gift/guest author?

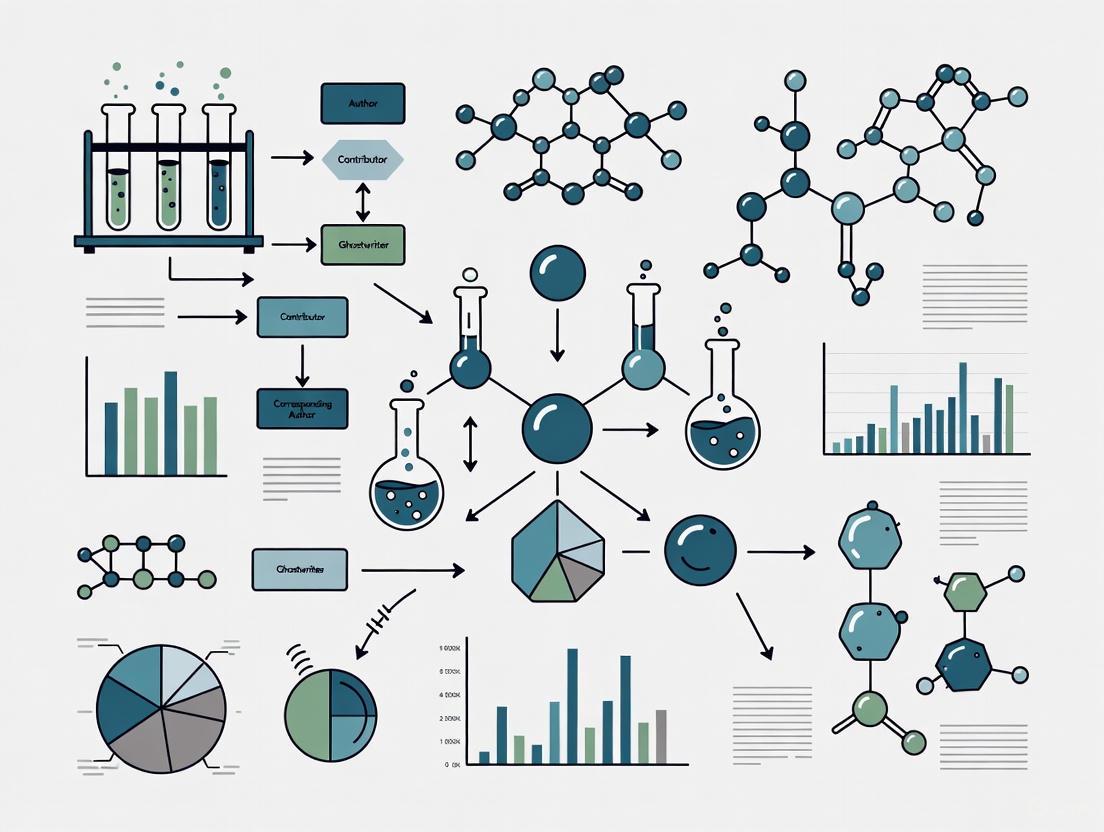

A legitimate co-author must meet specific criteria for substantive contribution and accountability. The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway to determining legitimate authorship based on international guidelines like those from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [3] [5].

What are the real-world scenarios where these practices typically occur?

Ghost Authorship Scenarios [1] [2]:

- Industry-Funded Clinical Trials: A pharmaceutical company sponsors a trial and hires a medical communication agency to write the manuscript. The company's employees or the medical writers who drafted the paper are not listed as authors, and the paper is published under the names of well-known academics to lend it credibility.

- Overcoming Publication Obstacles: A researcher with poor writing skills or limited time hires a professional scientific writer to draft or substantially edit the manuscript but does not credit them in the acknowledgments.

Gift Authorship Scenarios [1] [6]:

- Seniority-Based Inclusion: A junior researcher or PhD student includes their laboratory supervisor or head of department as an author, even if that senior person provided only high-level guidance or resources but no direct intellectual contribution to the research design, execution, or writing.

- Reciprocal Favors: A researcher includes a colleague as an author on their paper in return for the colleague including them on a future paper, or to maintain a good professional relationship, without a substantial contribution justifying it.

Guest Authorship Scenarios [1] [3]:

- Lending Credibility: An influential researcher in a field is added to the author list primarily to increase the manuscript's perceived status and improve its chances during journal review, despite minimal involvement.

- Coercive Inclusion: A principal investigator who secured the research funds insists that their name be included on all papers coming out of their laboratory, regardless of their direct intellectual input—a form of coercive authorship [1].

Our journal has put our manuscript on hold due to an authorship dispute. How can we resolve it?

Many journals, including those from Cell Press, will suspend the review process until the authors resolve the dispute among themselves or with the help of their institutions [5]. The following workflow outlines the recommended steps for resolution, moving from internal discussion to external escalation if necessary [7] [5].

What practical steps can my research team take to prevent authorship disputes?

Preventing disputes requires proactive planning and transparent communication.

1. Draft an Authorship Plan Early: Before the research begins, collaborators should discuss and agree upon expectations for authorship. This includes defining roles and establishing tentative author order based on projected contributions [5]. 2. Use a Contributor Taxonomy: Adopt a standardized taxonomy like CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) to define specific contributions clearly (e.g., conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, funding acquisition) [1] [5]. Many journals now require this. 3. Formalize Authorship with a Checklist: Use a checklist to ensure all contributors understand their responsibilities. The following table serves as a foundational tool for teams.

| Action Item | Completed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| We have held an initial meeting to discuss anticipated contributions and authorship. | ||

| We have consulted the target journal's authorship guidelines and the ICMJE recommendations. | ||

| We have documented tentative author order and the rationale. | ||

| We have assigned roles using a taxonomy like CRediT. | ||

| We have agreed on a process for resolving disagreements. | ||

| We have confirmed that all listed authors meet all four ICMJE criteria. | ||

| We have compiled a list of non-author contributors for the acknowledgments section. |

4. Acknowledge, Don't Gift: Use the Acknowledgments section to credit those who provided support that does not meet the bar for authorship. This can include a laboratory assistant who performed tests, a colleague who provided reagents, or a supervisor who gave general feedback [1]. Always obtain permission from those you plan to acknowledge [3].

| Resource | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| ICMJE Guidelines [1] [5] | The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidelines provide the most widely recognized criteria for authorship in biomedical journals. They define the four core requirements for authorship. |

| CRediT Taxonomy [1] [5] | The Contributor Roles Taxonomy is a high-level taxonomy with 14 standardized roles (e.g., Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft). It helps to clarify and document specific contributions transparently. |

| COPE Resources [1] [5] | The Committee on Publication Ethics provides extensive resources, including flowcharts for handling authorship disputes and case studies. It supports journals, publishers, and researchers in maintaining ethical standards. |

| ORCID iD [4] | A persistent digital identifier that helps ensure that your work is correctly attributed to you, distinguishing you from other researchers with similar names. |

| Institutional Ombuds Office [7] | A confidential, independent, and informal resource within a university or research institution that can help mediate disputes, including those related to authorship. |

Understanding the prevalence and nature of authorship misconduct is crucial for research integrity. Quantitative data helps contextualize the scale of the problem, while clear definitions aid in identification and prevention.

Key Definitions of Authorship Misconduct:

- Ghost Authorship: Occurs when an individual who has made a substantial contribution to the research or manuscript is omitted from the author list [1] [8] [4]. This is often done to conceal conflicts of interest, such as the involvement of pharmaceutical company employees [8].

- Gift/Guest Authorship: The practice of awarding authorship to individuals who have not made a substantial intellectual contribution to the work, often to leverage their seniority or reputation, or as a professional courtesy [1] [4]. Also known as honorary authorship [1].

Prevalence of Authorship Misconduct:

The table below summarizes key statistical findings on the prevalence of authorship misconduct from empirical studies.

Table 1: Statistical Prevalence of Authorship Misconduct

| Study Context/Discipline | Type of Misconduct | Prevalence Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public University in Ethiopia (2025 Survey) [9] | Any Form of Research Misconduct | 37.7% of participants | Self-reported engagement in at least one form of misconduct. |

| Authorship Misconduct | 47.5% of participants | The most common form of self-reported misconduct. | |

| Fabrication & Falsification | 40.6% of participants | Second most common form of self-reported misconduct. | |

| Six Medical Journals (2008 Survey) [8] | Ghost Authorship | Present in ~10% of papers | Survey finding reported in a BMJ study. |

Factors Associated with Misconduct: A 2025 cross-sectional survey identified that publication pressure was significantly associated with research misconduct, with those under pressure being 3.18 times more likely to engage in it [9]. Other contributing factors include the researcher's academic position and level of research experience, with junior researchers being more likely to report misbehavior [9].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs: Addressing Authorship Issues

This section provides direct, actionable guidance on preventing and resolving common authorship problems.

FAQ 1: How can we determine who qualifies as an author on our manuscript?

Answer: The most widely accepted standard is the four criteria from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [10]. To qualify as an author, an individual must meet all of the following conditions:

- Substantial Contribution: Contribute substantially to the conception/design of the work OR the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data.

- Drafting and Revision: Participate in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

- Approval: Approve the final version of the manuscript to be published.

- Accountability: Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part are appropriately investigated and resolved [10].

Individuals who do not meet all these criteria but provided assistance (e.g., general supervision, writing assistance, technical support) should be listed in the Acknowledgments section with a description of their contribution [1] [10].

FAQ 2: Our research team is facing a co-authorship dispute. What steps should we take to resolve it professionally?

Answer: Follow this structured protocol to navigate disputes professionally [11]:

- Establish Clear Guidelines Early: At the outset of any collaboration, have an open discussion to define roles, responsibilities, and authorship order based on expected contributions. Document this agreement.

- Communicate Openly and Respectfully: If a dispute arises, initiate a calm, respectful dialogue focused on the work and the agreed-upon guidelines. Practice active listening to understand all perspectives.

- Seek Mediation or Arbitration: If direct communication fails, involve a neutral third party, such as a senior faculty member not involved in the project or an institutional ombudsperson, to mediate the discussion. As a last resort, formal arbitration may be considered for a binding decision.

- Consider Legal Options as a Last Resort: Legal action is lengthy, costly, and can damage professional relationships. It should only be considered if all other resolution avenues have been exhausted and significant intellectual property rights are at stake.

- Learn from the Experience and Establish a Plan: After resolution, reflect on the causes of the dispute and use this knowledge to create a more comprehensive collaboration plan for future projects.

FAQ 3: A colleague suggested we add our department chair as a co-author as a courtesy, even though their contribution was minimal. Is this acceptable?

Answer: No, this practice, known as gift or guest authorship, is considered unethical [1] [4]. Adding a senior investigator, department head, or other superior who did not make a substantial intellectual contribution to the work misrepresents the actual contributions and undermines research transparency [1]. While it may seem like a gesture of respect or a way to boost the paper's credibility, it dilutes the meaning of authorship and can hold the "gifted" individual accountable for work they were not deeply involved in [1] [4]. Contributions that do not meet authorship criteria should be acknowledged in the Acknowledgments section instead [1].

FAQ 4: What is the proper way to disclose the use of an AI tool or a professional medical writer?

Answer: Transparency is key. AI tools cannot be listed as authors because they cannot take responsibility for the work [10]. However, their use must be explicitly disclosed in the manuscript, typically in the Methods or Acknowledgements section, specifying the tool and purpose (e.g., drafting, editing, translation) [10]. Similarly, professional medical writers or editors must be acknowledged in the Acknowledgements section, and their affiliation or funding source should be disclosed [8]. For extensive writing support, some journals require a detailed description of the writer's contribution and who paid for their services [8].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Authorship Misconduct

To effectively study authorship misconduct, researchers employ specific methodological approaches. The following diagram and protocol outline a standard method for conducting a survey-based study in this field.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for surveying authorship misconduct.

Detailed Methodology for a Cross-Sectional Survey on Authorship Misconduct [9]:

- Study Design: An institutional-based cross-sectional study.

- Population & Sampling: A random sample of researchers is selected from the target population (e.g., a university). A high response rate (e.g., 82%) is crucial for validity [9].

- Data Collection Tool: A self-administered, structured questionnaire. To ensure reliability and validity, the instrument can be adapted from questionnaires used in similar, previously published studies [9].

- Data Collection: The approved questionnaire is distributed to the randomly selected participants for self-completion.

- Data Analysis:

- Descriptive Statistics: Calculate frequencies, percentages, and confidence intervals to describe the basic features of the data and determine the prevalence (magnitude) of different forms of misconduct [9].

- Bivariate Analysis: Analyze crude associations between independent variables (e.g., career level, publication pressure) and the outcome (research misconduct).

- Multivariable Logistic Regression: Perform regression analysis to identify factors independently associated with research misconduct after controlling for other variables. Results are reported as Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) [9].

- Ethical Considerations: Ensure participant anonymity and confidentiality. The study protocol must be reviewed and approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee.

This table lists essential resources and tools for ensuring authorship integrity and conducting research on the topic.

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Addressing Authorship Misconduct

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| ICMJE Recommendations [10] | Guideline | Defines international standards for authorship criteria and ethical conduct in medical publication. |

| CRediT Taxonomy [1] | Contributor Role | Provides a high-level, standardized taxonomy of 14 roles (e.g., Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing) to clarify contributions. |

| ORCID iD [4] | Author Identification | A persistent digital identifier that helps distinguish researchers and ensure their work is correctly attributed. |

| Structured Questionnaire [9] | Research Tool | A validated instrument for collecting self-reported data on the prevalence and factors associated with research misconduct. |

| Focus Group Discussions [12] | Research Tool | A qualitative method to gather in-depth perspectives from various stakeholders (students, faculty, staff) to inform guideline development. |

| Acknowledgments Section [1] [10] | Publication Mechanism | The appropriate place in a manuscript to recognize individuals and entities that contributed but do not qualify for authorship. |

| Author Contribution Statement [12] [10] | Publication Mechanism | A mandatory section in many journals where each author's specific contributions are detailed, promoting transparency. |

FAQs on Authorship

What is the difference between ghost, guest, and gift authorship?

- Ghost Authorship occurs when an individual who has made a substantial contribution to the research or manuscript is not listed as an author. This often involves paid professional writers or researchers whose contributions are omitted from the byline and acknowledgments [1] [13].

- Guest Authorship involves listing an influential individual (e.g., a senior researcher or department head) as an author to boost the manuscript's credibility, despite their lack of substantial contribution to the research. This is sometimes a coercive practice where superiors insist on being included [1] [13].

- Gift Authorship is the practice of granting authorship to someone as a "gift," such as a colleague, junior researcher, or supervisor, as a favor or to maintain good relations, even if they do not meet the authorship criteria [1] [13].

Why are these practices considered unethical? Ghost, guest, and gift authorship are considered questionable research practices (QRPs) because they undermine transparency and accountability in science [1]. They lead to misattribution of credit, where individuals receive either too much or too little credit for the work performed. Furthermore, all listed authors are accountable for the published work; if problems arise, honorary authors could be held responsible for research they were not deeply involved with, while ghost authors avoid accountability [1] [13].

What are the potential consequences of misattributed authorship? Engaging in misattributed authorship can seriously damage a researcher's career and reputation [1]. For individuals, being omitted as an author (ghost authorship) can hinder career advancement, which often depends on publication records [1] [14]. At a broader level, these practices erode trust in scientific institutions and the research record. One study found that increased reports of gift authorship and ghost authorship were associated with lower levels of trust in research institutions [15]. Journals may reject manuscripts or even retract published papers if authorship disputes are discovered [5] [13].

How can I prevent authorship disputes in my research team? Prevention is the most effective strategy [13].

- Have Early Discussions: Before starting research, have a face-to-face meeting with all collaborators to discuss authorship expectations, including who will be an author and the intended order of authors [5] [13].

- Follow Established Guidelines: Adhere to authorship criteria from recognized bodies like the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) or your target journal [1] [13]. The ICMJE recommends four criteria for authorship, including substantial contributions, drafting or revising the work, final approval, and accountability [5] [13].

- Use Contributor Taxonomies: Employ a contributor role taxonomy, such as the CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy), to define and document each person's specific contributions clearly [1] [5] [13].

- Put It in Writing: Keep a record of the decisions made during authorship discussions [13].

What should I do if I am involved in an authorship dispute?

- Internal Resolution: The first step is to try to resolve the dispute directly with the co-authors involved [7] [5].

- Institutional Guidance: If internal resolution fails, contact the research administration at your institution (e.g., department chair, Dean) [15]. However, be aware that power imbalances can make this difficult, and institutional administrators may have limited authority over all team members, especially in multi-institutional collaborations [7] [15].

- Journal Policies: If the dispute involves a manuscript submitted to a journal, inform the handling editor. Journals like those from Cell Press will suspend the manuscript's processing until the authors resolve the dispute [5]. For post-publication disputes, a correction may be required [5].

- Alternative Dispute Resolution: Some researchers have proposed independent mediation or arbitration services to help resolve disputes, particularly when power differentials are large [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: A colleague expects to be an author but did not contribute substantially.

- Solution: Use the acknowledgment section to recognize contributions that do not meet the bar for authorship. This can include providing materials, technical assistance, feedback, or proofreading [1] [13]. Frame the decision by referring to the journal's or your institution's formal authorship guidelines to make the conversation objective rather than personal.

Problem: A contributor was left off the author list (Ghost Author).

- Solution: If you realize a contributor was omitted before publication, immediately bring this to the attention of the corresponding author and all co-authors. Emphasize that ghost authorship is considered scientific misconduct by most journal editors and that its discovery could lead to the paper's rejection or retraction [13]. The author list must be modified to include all qualifying contributors, with their written approval [5].

Problem: Disagreement over the order of authors on the byline.

- Solution: Refer back to the initial authorship discussions and documented agreements. Author order should reflect the relative substantive contributions to the work [7]. Many fields follow the convention where the first author contributes the most, and the last author provides senior oversight [7]. If equal contribution was made, many journals allow for a note designating "co-first authors" or "co-senior authors" [7] [13].

Data on Authorship Misconduct and Trust

The following table summarizes quantitative data from a study on the association between misattributed authorship and trust in research institutions [15].

| Metric | Finding |

|---|---|

| Association with Trust | Increased reporting of gift authorship, author displacement, and ghost authorship was associated with significantly lower trust scores in the institution's administration (P<0.001). |

| Impact of Clear Policies | Institutions that had made their authorship policies known were awarded the highest median trust scores (3.06 on a 1-4 scale). |

| Preferred Dispute Authority | Only 17.8% of respondents favored their own institution's administration as the best authority to honestly investigate an authorship dispute. |

| Tool / Resource | Function |

|---|---|

| ICMJE Guidelines | Provides widely recognized and authoritative criteria for determining who qualifies for authorship [1] [5] [13]. |

| CRediT Taxonomy | A high-level taxonomy with 14 standardized roles (e.g., Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing) to clarify individual contributions transparently [1] [5] [13]. |

| COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics) | Provides resources, case studies, and guidelines for handling complex publication ethics issues, including authorship disputes [5] [13]. |

| Institutional Authorship Policy | An internal document that sets clear, field-specific expectations and procedures for assigning authorship, helping to prevent disputes [15] [13]. |

| Authorship Agreement Form | A documented plan, signed by all collaborators, that outlines anticipated author order and contributions at the start of a project [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Resolving an Authorship Dispute

This methodology outlines the steps recommended by journals and ethics bodies when an authorship dispute arises [7] [5] [13].

1. Initiate Internal Discussion

- Action: The concerned party should communicate their grievance in writing to the corresponding author and all other co-authors.

- Rationale: The first and preferred step is for the researchers to resolve the issue amongst themselves. This direct communication can often clarify misunderstandings.

2. Escalate to Institutional Administration

- Action: If internal discussion fails, the issue should be brought to the relevant institutional administrators (e.g., department chairs, deans) at the institution where the research was primarily conducted.

- Rationale: Institutions are often best positioned to investigate the circumstances surrounding the research and the dispute [15]. However, their authority may be limited in multi-institutional collaborations [7].

3. Engage Journal Editors

- Action: For manuscripts under consideration, the handling editor must be informed of the dispute. For published papers, the journal should be contacted.

- Rationale: Journals have a responsibility to ensure the integrity of their publication record. They will typically halt the peer-review process until the dispute is resolved and may require a formal correction for published articles [5].

4. Seek Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

- Action: If other avenues fail, parties can seek mediation or arbitration from an independent body.

- Rationale: ADR provides a structured, neutral process for resolving disputes, which is particularly valuable when there are significant power imbalances between the parties involved [7].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Pathway for Determining Authorship

A clear, pre-established pathway for determining authorship can prevent many disputes. The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for deciding who should be listed as an author and who should be acknowledged, based on criteria from the ICMJE and other guidelines [1] [5] [13].

In the high-stakes laboratory of academic and industrial research, the "publish or perish" imperative creates a high-pressure environment where authorship disputes frequently erupt. These disputes function like system errors in complex equipment—they reveal underlying flaws in the research ecosystem's design and operation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these errors is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for maintaining research integrity, ensuring proper credit attribution, and preventing the waste of resources on disputes that can derail careers and projects. This technical support center frames authorship disputes within the broader thesis that they are predictable, preventable, and manageable system failures, often rooted in dysfunctional power dynamics and the corrosive effects of the "publish or perish" culture [7].

Diagnosing the Core Malfunction: Authorship Pathology and Prevalence

Authorship disputes often arise from a fundamental misalignment between established ethical guidelines and on-the-ground practices. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) proposes four criteria for authorship, which include substantial contributions to conception/design, drafting/revising the work, final approval, and accountability [16]. However, in practice, these criteria are often circumvented, leading to several common pathologies.

The table below classifies these aberrant authorship types, their definitions, and their estimated prevalence, which can be considered a key performance indicator of system health.

Table 1: Pathology of Authorship Types

| Authorship Type | Definition | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Genuine Author | An individual who meets all established criteria for authorship, including substantial contribution and accountability [17]. | N/A (Ideal State) |

| Honorary/Guest Author | An individual listed as an author despite not making a qualifying contribution; often added due to seniority, to enhance credibility, or as a favor [17]. | Very common (>50% of articles) [17] |

| Ghost Author | An individual who makes a substantial contribution (e.g., writing, analysis) but is not listed as an author, often to conceal industry involvement or conflicts of interest [8]. | Common (20-50% of articles) [17] |

| Gold Author | A paid individual who authors a paper to overstate the merits of a product (e.g., a new drug) while ignoring its drawbacks [17]. | Uncommon (5-20%) [17] |

Quantitative data further illuminates the scale of the problem. A study of retracted articles found that 7.4% of retractions were due directly to authorship disputes [18]. Surveys suggest that between 30% to 66% of researchers have been involved in an authorship disagreement [7]. In medical fields, one study found 21% of articles had honorary authors and 8% had ghost authors [18]. These figures represent significant error rates that undermine system reliability.

System Analysis: The Root Cause of Failures

The 'Publish or Perish' Operating Pressure

The "publish or perish" culture creates an environment where publication volume and placement in high-impact journals become the primary metrics for career advancement, funding, and reputation [16]. This pressure distorts incentives, making authorship a commodity to be hoarded or traded rather than a credit to be earned. For junior researchers, publication is "everything," making them vulnerable to exploitation [16]. Simultaneously, senior researchers are under pressure to "maintain rank or move along the tenure track," which can tempt them to engage in or tolerate abusive authorship practices [16].

Power Dynamics and Circuit Design

Power differentials are a critical fault line. Senior researchers (PIs) often control resources, funding, and career trajectories, creating a system where they can dictate authorship credit [7]. This can lead to "proxy wars," where senior researchers with conflicting advice use a junior researcher as a battleground, leaving the junior researcher confused and intimidated [19]. In extreme cases, a PI may operate under the principle that "everything that was done in his division belonged to the director," leading to the exclusion of genuine contributors [17]. This power imbalance is a primary reason why informal dispute resolution often fails; the vulnerable party fears retaliation [7].

Protocol Ambiguity and Resource Contention

The absence of clear, universally adhered-to protocols for assigning authorship and order is a fundamental design flaw. While guidelines like ICMJE's exist, many researchers are ignorant of them or disagree with their provisions [7]. Furthermore, authorship is a limited resource; positions like first author and last author are particularly valuable for career advancement, creating intense competition [7]. In large, multi-institutional, and interdisciplinary collaborations—increasingly the norm in science—the lack of a pre-established contribution management protocol makes disputes almost inevitable [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Authorship Disputes

When a authorship dispute error occurs, the following systematic troubleshooting protocol is recommended. The flowchart below visualizes the escalation path from informal to formal resolution mechanisms.

Step 1: Informal Resolution Efforts

The first and preferred step is always to attempt informal resolution. This involves:

- Facilitating Open Discussions and Documentation: Organize a team meeting with a clear agenda to discuss the disagreement [19]. The key is to get the conflicting parties, especially senior researchers, in a room to make it their shared problem to solve. It is critical to take clear notes during these discussions and distribute them afterwards to hold all attendees accountable to what has been agreed upon [19].

- Involving Impartial Mediators: If direct discussion fails, confide in a trusted third party [19]. This could be a senior person or colleague not involved in the project who can act as a neutral mediator. A tactful way to do this is to suggest inviting this person to help review the work and figure out where things might have gone wrong [19]. Their involvement can sometimes "shame the supervisor out of their position" without needing to escalate formally [19].

Step 2: Formal Adjudication Mechanisms

When informal efforts fail, and the dispute involves significant power imbalances or intractable positions, formal mechanisms must be initiated.

- Institutional Policies and Procedures: Universities and research institutions have formal policies for dispute resolution. A researcher can inform an institutional administrator, such as a department chair, Dean, or a dedicated research integrity officer [19] [7]. These bodies can review the case, gather evidence, and render a binding decision. However, their authority may be limited in multi-institutional collaborations [7].

- Journal Arbitration: For disputes arising after submission or publication, journals can act as arbiters. Because authors recognize journals' authority over manuscripts, journals are well-placed to facilitate alternative dispute resolution processes, including mediation or arbitration [7]. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) provides guidelines for journals in these situations.

Step 3: The "Scorched Earth" Solution: Retraction

In the worst-case scenario, where a dispute cannot be resolved through any other means, the paper may be retracted. This is a "scorched earth" solution where nobody wins [7]. The authors lose credit, the readers lose access to potentially sound science, and the funders see no return on their investment. It is the ultimate system failure.

Research Reagent Solutions: Proactive System Safeguards

Just as a well-stocked lab has reagents to prevent experimental failure, the following tools are essential for preventing authorship disputes.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Preventing Authorship Disputes

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Team Authorship Policy | A pre-project agreement defining authorship criteria and order [20]. | Draft and sign at the start of a collaboration. Discuss hypothetical scenarios and how they would be handled. |

| CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) | A standardized list of 14 roles (e.g., Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing) to clarify contributions [18]. | Used when submitting the manuscript to provide a transparent, machine-readable record of who did what. |

| ICMJE Guidelines | The most widely recognized benchmark for defining a legitimate author [16]. | Used as a reference point for developing team-specific policies and for training lab members. |

| Written Documentation | Records of meetings, email correspondence, and data management plans. | Serves as evidence of contributions and agreements if a dispute arises. |

| Institutional Ombudsman | A confidential, impartial, and informal resource for conflict resolution [19]. | Consulted early when a researcher feels uncomfortable raising an issue through formal channels. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: A senior colleague demanded to be a co-author on my paper despite minimal contribution. What are my options? This is a classic case of attempted honorary authorship. Your first step should be to refer to your team's pre-established authorship policy or the journal's adopted guidelines (e.g., ICMJE) [16]. Politely explain that according to these criteria, their contribution may not qualify for authorship but could be acknowledged. If this is too difficult due to power dynamics, seek advice from a trusted senior mentor or your institution's ombudsman [19]. Involving an impartial mediator can help navigate this sensitive situation.

Q2: I discovered a "ghost author" from a pharmaceutical company was involved in a study I am referencing. How does this affect the research integrity? Ghost authorship, particularly when used to obscure industry ties, is a serious ethical breach [8]. It deceives the research community about the true origins and potential biases of the work, as the reader cannot properly assess conflicts of interest [8]. This practice may violate standards set by COPE and other bodies. When you encounter this, you should critically evaluate the paper's conclusions, check for undisclosed conflicts of interest, and consider the potential for biased data interpretation [8].

Q3: Our multi-institutional research team is deadlocked on authorship order. How can we break the impasse? When internal discussion fails, especially across institutions, formal mediation or arbitration is the recommended path [7]. Since no single institution may have authority over all parties, consider proposing the use of an independent third-party mediator agreed upon by all institutions. Journals, which have authority over the manuscript, can also be asked to facilitate an alternative dispute resolution process before the paper is accepted [7].

Q4: As a junior researcher, I feel my PI is unfairly excluding me from authorship. What can I do without damaging my career? This is a difficult situation due to the clear power imbalance. Start by gathering all evidence of your contribution (emails, lab notes, data files) [19]. If you have a supportive mentor outside the direct conflict, confide in them to explore options [19]. You can also approach your institution's research degree coordinator, postdoctoral officer, or human resources manager [19]. These offices are designed to help in such situations while aiming to protect vulnerable researchers.

Implementing Ethical Authorship: Frameworks, Tools, and Best Practices for Research Teams

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Resolving Common Authorship Scenarios

This guide helps you diagnose and correct frequent issues in assigning authorship according to ICMJE criteria.

| Observed Problem | Possible Causes (ICMJE Criterion Violation) | Recommended Corrective Action | Prevention Tips for Future Projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghost Authorship: An individual made a substantial contribution but is omitted from the author list [1]. | Failure to recognize a substantive intellectual contribution (Criterion 1); Often involves paid writers or researchers whose roles are not disclosed [1]. | Include the contributor as an author if they meet all four criteria. If their role was limited (e.g., writing assistance only), acknowledge them in the Acknowledgments section with a description of their contribution [21] [1]. | Discuss authorship expectations with all team members early in the project. Implement a transparency policy where all writing assistance is reported. |

| Gift/Guest Authorship: A person is listed as an author despite not meeting all ICMJE criteria [1]. | Inclusion based on seniority, department head status, or to increase credibility without substantive intellectual contribution (Violates Criterion 1); The individual did not participate in drafting/revision (Criterion 2) or give final approval (Criterion 3) [22] [23]. | Remove the individual from the author list. Acknowledge their non-substantive contribution (e.g., general supervision, administrative support, funding acquisition) in the Acknowledgments section [21] [23]. | Establish clear authorship guidelines at the institutional level. Use a contributorship model to detail each author's specific role [24]. |

| Author Displacement: An author is listed in a position that does not reflect their actual contribution [24]. | Although not a direct violation of the four criteria, improper ordering undermines accountability and can be a form of misattribution [24]. | The author group should collectively decide and justify the author order before manuscript submission. Revisit and confirm the order reflects relative contributions [21]. | Decide authorship order early in the project as a team. Document the rationale for the order. Some journals allow a explanation of author order contributions. |

| Dispute over Criterion #2 or #3: A contributor who meets Criterion 1 is denied the opportunity to review the manuscript or give final approval. | Violation of the spirit of the criteria. The ICMJE states that all who meet the first criterion should have the chance to meet criteria 2 and 3 [21]. | Ensure all qualifying contributors participate in the drafting/review process and approve the final version to be published. This is a non-negotiable requirement for authorship [21]. | Circulate drafts to all potential authors in a timely manner. Obtain formal, written final approval from every author before submission. |

| Unclear Accountability: When questions arise about the work, it is unclear which author is responsible for specific parts. | Incomplete fulfillment of Criterion 4, which requires authors to be accountable for their work and to identify which co-author is responsible for other parts [21]. | Authors must reconfirm their specific responsibilities and be able to identify which co-author is accountable for each component of the research [21]. | Use the CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) model to define each author's role clearly during the manuscript preparation process [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Addressing Modern Authorship Challenges

This guide addresses specific scenarios that arise in contemporary research environments, including the use of AI.

| Scenario / Tool | Associated Risk | Application of ICMJE Criteria & Solution | Documentation Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large, Multi-Center Trials (Group Authorship) | Ambiguity in individual accountability; confe credit where it's due [22]. | The group should decide who qualifies as an author before the work begins [21]. All listed group members must meet all four criteria [21]. The corresponding author must specify the group name and identify individual authors [21]. | Clearly state the individual authors who take responsibility. The byline should list the group name with named individuals, or the individuals should be listed as writing on the group's behalf [21]. |

| Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools | Inability of AI to take responsibility; potential for incorrect or biased output; plagiarism [21]. | AI tools cannot be authors [21]. Humans are solely responsible for any submitted material that includes AI-generated content [21]. Use of AI must be disclosed transparently. | For writing assistance: Describe the use in the Acknowledgments section [21]. For data collection, analysis, or figure generation: Describe the use in the Methods section [21]. |

| Local Collaborators in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) | Exclusion of local researchers from authorship when data is from LMICs [21]. | Failure to include qualified local investigators should prompt questioning and may be grounds for journal rejection. Inclusion adds fairness, context, and implications to the research [21]. | Collaborate and offer co-authorship to colleagues in the locations where the research is conducted, provided they meet the four criteria [21]. |

| Industry-Sponsored or Funded Research | Ghostwriting by company-hired writers; hidden conflicts of interest [1]. | All individuals who meet the authorship criteria must be named, regardless of their institutional affiliation (e.g., industry representatives) [23]. The use of undisclosed "ghostwriters" is prohibited [23]. | Disclose all financial support and relevant affiliations. Report and acknowledge the specific role of any professional writers or other contributors provided by the sponsor [1] [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our department head provided the funding and lab space but had no direct involvement in the research design, drafting, or approval. Should they be an author?

A: No. According to the ICMJE, acquisition of funding, general supervision of a research group, or general administrative support alone do not qualify an individual for authorship [21]. These contributions should be rightfully acknowledged in the Acknowledgments section [23].

Q2: A colleague provided a critical reagent that made our entire study possible. Do they deserve authorship?

A: Providing a reagent or material alone is not sufficient for authorship. This type of contribution should be acknowledged in the manuscript's Acknowledgments section rather than conferring authorship [21] [23].

Q3: Can we use a professional editing service to improve the language and clarity of our manuscript before submission?

A: Yes, but this must be transparently reported. If the service was limited to writing assistance, language editing, or proofreading, this does not qualify the editor for authorship. The service should be acknowledged, often with a statement like, "The authors thank [Company/Individual] for providing editorial/proofreading support" [1]. The use of AI-assisted technology for writing must also be disclosed in the acknowledgment section [21].

Q4: What should we do if a co-author refuses to give final approval for the manuscript version we all agreed upon?

A: This is a serious situation that prevents the manuscript from being submitted, as final approval is a mandatory ICMJE criterion [21]. The author group should first try to understand and resolve the co-author's concerns. If an agreement cannot be reached, the institution(s) where the work was performed should be asked to investigate the dispute [21].

Q5: Is the first author always the person who did the experiments and wrote the first draft?

A: While this is a common convention, the ICMJE does not prescribe a specific order. The criteria used to determine the author order are to be decided collectively by the author group [21]. It is the collective responsibility of the authors to determine a fair order that reflects the relative contributions.

Q6: Who is responsible for ensuring all authors meet the ICMJE criteria?

A: It is the collective responsibility of the authors, not the journal editor [21]. The corresponding author often takes a lead role in ensuring administrative requirements are met, but all listed authors must individually and collectively ensure that everyone listed fulfills all four criteria [21].

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions for Authorship Integrity

The following "reagents" are essential procedural tools for preventing authorship disputes and maintaining integrity in research publications.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Maintaining Authorship Integrity |

|---|---|

| ICMJE Authorship Criteria | The definitive standard for determining who qualifies for authorship. Serves as the foundational protocol for all authorship decisions [21]. |

| Contributorship Model (e.g., CRediT) | A detailed taxonomy that allows for a precise description of each author's contribution (e.g., conceptualization, methodology, writing) [1]. This adds transparency and removes ambiguity. |

| Written Authorship Agreement | A document, created early in the project, that outlines expected author roles, responsibilities, and the anticipated order of authorship. This prevents future disputes [23]. |

| Institutional Authorship Policy | A set of clear rules and guidance established by a research institution to govern authorship practices. This fosters a culture of integrity and provides a framework for dispute resolution [24]. |

| Acknowledgments Section | The designated area in a manuscript to recognize individuals and organizations that contributed to the research but do not qualify for authorship, ensuring they receive appropriate credit [21] [23]. |

Leveraging the CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) System for Transparent Contribution Statements

The Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) is a standardized, controlled vocabulary of 14 roles that capture the range of contributions typically made to scholarly research outputs. Developed to address the limitations of traditional author lists, CRediT provides a transparent framework for specifying "who did what" in a research project [25] [26]. This technical support center provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with comprehensive guidance for implementing CRediT to mitigate authorship disputes and enhance research integrity.

The fundamental problem CRediT addresses is the inability of simple author lists to represent the diversity of researcher contributions to published work [25]. This shortcoming has led to several challenging issues in research publication, including authorship disputes, the inability to recognize early career researcher contributions, "ghost authorship" where contributors are not acknowledged, and "guest authorship" where individuals are listed despite minimal contributions [25] [27]. In drug development research, where multidisciplinary teams collaborate on complex projects, these challenges are particularly pronounced.

CRediT was developed following a 2012 workshop hosted by the Wellcome Trust and Harvard University that brought together researchers, research institutions, publishers, and funders [25] [26]. The taxonomy was formally introduced in 2015 and became an ANSI/NISO standard in 2022, ensuring its stability and widespread adoption [26]. It is now used by over 50 major publishers and thousands of journals worldwide [26].

CRediT Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary purpose of the CRediT taxonomy? CRediT aims to provide transparency in contributions to scholarly published work, enabling improved systems of attribution, credit, and accountability [28]. It offers authors the opportunity to share an accurate and detailed description of their diverse contributions to the published work [29].

Q2: Does using CRediT determine who qualifies for authorship? No. CRediT is not intended to determine who qualifies as an author [30]. Each author may have one or more CRediT roles, but having a role does not automatically qualify someone as an author. Authorship is still determined according to journal guidelines which are often based on ICMJE requirements [30].

Q3: Who is responsible for ensuring the accuracy of CRediT statements? The corresponding author is responsible for ensuring that the contribution descriptions are accurate and agreed upon by all authors [29]. This responsibility includes verifying that all authors have approved the CRediT statement before submission.

Q4: Can one contributor have multiple CRediT roles? Yes. Authors may have contributed in multiple roles, and the taxonomy allows for assigning multiple contribution types to a single individual [29]. For example, a researcher might have contributed to Conceptualization, Methodology, and Writing - original draft.

Q5: Where and when should CRediT statements be provided? CRediT statements should be provided during the submission process and typically appear above the acknowledgment section of the published paper [29]. Many publishers now incorporate CRediT directly into their submission systems.

Q6: How does CRediT help address ghost authorship? By requiring transparent documentation of all contributions, CRediT helps reveal individuals who have made substantive contributions but might otherwise not be acknowledged, thereby reducing the potential for ghost authorship [27]. This is particularly valuable in drug development research where multiple stakeholders are involved.

Q7: Are there standardized templates available for creating CRediT statements? Yes. Standardized templates are available in various formats including standard contribution statements, detailed contribution statements, journal-specific formats, and institutional formats [31]. These ensure consistency, accuracy, and compliance with CRediT taxonomy standards.

Troubleshooting Common CRediT Implementation Issues

Problem: Disagreement Among Collaborators About Role Assignments Issue: Team members have different interpretations of their contributions and deserve different CRediT roles.

Solution:

- Initiate early discussions about contributor roles at the project planning stage

- Use the official CRediT definitions as a neutral reference point [29] [30]

- Document proposed contributions in a collaboration agreement

- If disputes arise, refer to journal policies or seek mediation from institutional research offices

- Remember that multiple contributors can be assigned the same role (e.g., multiple investigators)

Problem: Uncertainty About Distinction Between Similar Roles Issue: Confusion about differences between closely related roles, particularly Methodology vs. Investigation, or Validation vs. Formal analysis.

Solution: Consult the official definitions:

- Methodology: "Development or design of methodology; creation of models" [29]

- Investigation: "Conducting a research and investigation process, specifically performing the experiments, or data/evidence collection" [29]

- Formal analysis: "Application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyze or synthesize study data" [29]

- Validation: "Verification, whether as a part of the activity or separate, of the overall replication/reproducibility of results/experiments and other research outputs" [29]

Problem: Journal Has Specific CRediT Requirements Issue: Target journal has unique formatting or implementation requirements for CRediT statements.

Solution:

- Check author guidelines before submission

- Use journal-specific templates when available [31]

- Contact the journal's help desk for clarification

- Consult the CASRAI website for journal-specific implementation guides [31] [32]

Problem: Technical Issues With Submission System Issue: The journal's online submission system doesn't properly accept or display CRediT information.

Solution:

- Ensure you're using the latest browser version

- Contact the journal's technical support team

- Provide the CRediT statement in both the designated fields and as a separate file if necessary

- For persistent issues, consult the CRediT Help Desk [32]

CRediT Taxonomy: Roles, Definitions, and Experimental Context

The 14 CRediT Roles and Their Applications

Table 1: Complete CRediT Taxonomy with Definitions and Experimental Applications

| CRediT Role | Definition | Application in Experimental Research |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptualization | Ideas; formulation or evolution of overarching research goals and aims | Formulating research hypothesis, defining scientific questions, establishing experimental framework |

| Methodology | Development or design of methodology; creation of models | Designing experimental protocols, establishing procedures, creating theoretical models |

| Software | Programming, software development; designing computer programs; implementation of code | Developing data analysis scripts, creating specialized analysis tools, programming simulations |

| Validation | Verification of replication/reproducibility of results/experiments | Repeating key experiments, verifying analytical methods, confirming results robustness |

| Formal Analysis | Application of statistical, mathematical, computational techniques to analyze study data | Performing statistical tests, computational analysis, mathematical modeling of data |

| Investigation | Conducting research investigation; performing experiments; data/evidence collection | Conducting laboratory experiments, collecting field data, performing clinical observations |

| Resources | Provision of study materials, reagents, materials, patients, instrumentation | Providing cell lines, chemical compounds, patient samples, specialized equipment |

| Data Curation | Management activities to annotate, scrub data; maintain research data | Data cleaning, annotation, metadata creation, database management, curation for reuse |

| Writing - Original Draft | Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing initial draft | Drafting manuscript sections, preparing initial figures, substantive translation |

| Writing - Review & Editing | Critical review, commentary or revision by those from original research group | Revising manuscript content, providing critical feedback, editing for clarity and accuracy |

| Visualization | Preparation, creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically visualization/data presentation | Creating figures, diagrams, data visualizations, graphical abstracts |

| Supervision | Oversight and leadership responsibility for research activity planning and execution | Providing research direction, mentoring team members, ensuring research quality |

| Project Administration | Management and coordination responsibility for research activity planning and execution | Coordinating collaborations, managing timelines, ensuring regulatory compliance |

| Funding Acquisition | Acquisition of financial support for project leading to publication | Securing research grants, obtaining institutional funding, identifying funding sources |

Quantitative Analysis of CRediT Implementation

Recent research has analyzed patterns of CRediT implementation across disciplines. A 2024 study examining over 700,000 articles published between 2017-2024 in Elsevier and PLOS journals revealed significant disciplinary differences in contribution patterns [33].

Table 2: Disciplinary Patterns in CRediT Implementation (Based on Analysis of 700,000+ Articles)

| Disciplinary Area | Most Frequent Contribution Roles | Notable Implementation Patterns |

|---|---|---|

| Health Sciences | Investigation, Methodology, Formal Analysis | High prevalence of Writing - Review & Editing across all authors |

| Life Sciences | Investigation, Methodology, Validation | Strong supervision patterns with clear leadership roles |

| Physical Sciences | Software, Formal Analysis, Visualization | High incidence of multiple roles per contributor |

| Social Sciences | Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Data Curation | Significant software development contributions |

| Multidisciplinary | Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization | Balanced distribution across most contribution types |

Experimental Protocols for Contribution Documentation

Protocol 1: Establishing Contribution Management Plans

Purpose: To preemptively address potential authorship disputes by establishing clear contribution expectations at project inception.

Materials Needed:

Procedure:

- Initial Team Meeting: Discuss potential contributions using CRediT taxonomy as framework

- Draft Contribution Plan: Assign anticipated roles to each team member

- Document Agreement: Formalize understanding in collaboration agreement

- Periodic Review: Revisit contribution allocations at project milestones

- Final Verification: Confirm actual contributions before manuscript submission

Expected Outcomes: Reduced authorship disputes, clear expectations, documented agreement for reference in case of disagreements.

Protocol 2: Implementing CRediT in Multi-Center Trials

Purpose: To standardize contribution tracking across multiple research sites in complex drug development studies.

Materials Needed:

- Standardized CRediT data collection form

- Centralized database for contribution tracking

- Communication platform for distributed teams

Procedure:

- Template Distribution: Provide CRediT definitions and collection forms to all site investigators

- Centralized Coordination: Designate corresponding author as contribution coordinator

- Regular Updates: Collect contribution information at regular intervals throughout study

- Verification Process: Confirm contributions with each contributor before manuscript submission

- Statement Generation: Compile final CRediT statement for inclusion in manuscript

Expected Outcomes: Consistent attribution across distributed teams, comprehensive contribution capture, reduced ghost authorship in multi-center trials.

Visualization of CRediT Implementation Workflow

CRediT Implementation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential process for implementing CRediT throughout a research project, from initial planning to final submission.

Research Reagent Solutions for Contribution Documentation

Table 3: Essential Resources for Implementing CRediT in Research Projects

| Resource/Solution | Function | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Standard CRediT Template | Provides consistent format for creating contribution statements | CASRAI website [31] |

| Journal-Specific Templates | Ensures compliance with particular journal requirements | Publisher author guidelines [31] |

| CRediT Help Desk Support | Provides direct assistance with implementation questions | CASRAI Support Center [32] |

| Interactive CRediT Explorer | Allows users to explore all 14 contributor roles in detail | CASRAI website [26] |

| Implementation Guides | Tailored resources for institutions, publishers, and researchers | CASRAI knowledge base [32] |

| Contribution Management Tools | Digital platforms for tracking contributions throughout projects | Various commercial and open-source solutions |

| CRediT Statement Validator | Checks statements for completeness and compliance | JATS4R recommendation tools [28] |

The CRediT taxonomy represents a significant advancement in research transparency by providing a standardized framework for acknowledging diverse contributions to scholarly work. For drug development professionals and researchers working in complex, multidisciplinary teams, systematic implementation of CRediT can substantially reduce authorship disputes, minimize ghost authorship, and ensure proper recognition for all contributors. The troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and resources provided in this technical support center offer practical solutions for integrating CRediT into research workflows, ultimately supporting research integrity and equitable attribution practices.

Why is a collaborative authorship plan necessary?

Authorship plans are crucial because authorship confers credit and has important academic, social, and financial implications, but it also implies responsibility and accountability for the published work [34]. Without a clear plan, teams are more susceptible to disputes, which are often rooted in deeper issues of misconduct and mistrust, and can be exacerbated by institutional pressures to publish [24]. A proactive plan ensures that all contributors who have made substantive intellectual contributions are given credit as authors and understand their responsibilities [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles

Q1: What is the definition of authorship? According to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), an author is someone who meets all four of the following criteria [34]:

- Substantial contributions to the conception/design, data acquisition/analysis/interpretation; AND

- Drafting or critically revising the work for important intellectual content; AND

- Final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Q2: What is ghost authorship and honorary authorship?

- Ghost Authorship: Occurs when an individual who has made a substantial contribution (e.g., a researcher or writer) is omitted from the author list. This is unethical as it withholds credit and can be used to obscure conflicts of interest [6].

- Honorary/Guest Authorship: Occurs when an individual (often a senior researcher) is listed as an author without having provided a significant contribution to the study. This dilutes the credit deserved by the actual contributors [6].

Q3: Who is responsible for determining authorship? It is the collective responsibility of the authors—not the journal or publisher—to determine that all individuals named as authors meet the agreed-upon criteria. Journals generally will not investigate or arbitrate authorship disputes [34] [35].

Planning and Setup

Q4: When should we start discussing the authorship plan? At the very outset of a research project. Ideally, the team should decide on authorship guidelines when planning the work and confirm this before manuscript submission [34] [36].

Q5: What should a written authorship agreement include? A written agreement helps prevent misunderstandings. It should outline [37] [36]:

- The criteria for authorship (e.g., based on ICMJE guidelines).

- The anticipated roles and responsibilities of each contributor.

- The rationale and method for determining the order of authors.

- The process for managing changes to the author list.

- A plan for documenting contributions (see Contribution Matrix below).

Q6: How do we handle authorship in multi-disciplinary collaborations? Different disciplines have varying authorship norms (e.g., order of authors, contribution expectations). It is critical to have open discussions about these differences early on to align expectations and agree on a common standard for the project [37] [36].

Implementation and Tracking

Q7: How can we track contributions fairly? Using a contribution matrix is an effective way to track and quantify each team member's input throughout the project. This provides an objective record to inform authorship discussions [37].

Table: Author Contribution Matrix Template

| Team Member | Conception | Design | Execution | Analysis | Interpretation | Drafting | Critical Revision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Researcher A | |||||||

| Statistician B | |||||||

| Data Analyst C |

Q8: What is the role of the Corresponding Author? The Corresponding Author takes primary responsibility for communication with the journal and ensures that all administrative tasks are completed. This includes [35]:

- Ensuring all listed authors have approved the manuscript before submission.

- Managing all communication between the journal and all co-authors.

- Ensuring that disclosures, declarations, and data statements are included correctly.

Troubleshooting: Resolving Disputes and Making Changes

Q9: What is the process for resolving an authorship dispute? If a dispute arises, address it constructively [37] [36]:

- Listen to concerns from all parties involved.

- Refer to the initial written agreement and contribution records.

- If internal resolution fails, seek informal, impartial guidance from a research governance or ethics office.

- As a last resort, the issue may be referred for a formal institutional review, which could involve an investigation into research misconduct.

Q10: Can we add or remove an author after the manuscript is submitted? Any change to the author list after submission requires the approval of every author. Journals typically require a signed statement of agreement from all listed authors and the author to be removed or added. Changes are generally not permitted after manuscript acceptance [34] [35].

Q11: How should we handle contributors who do not qualify for authorship? Individuals who do not meet all authorship criteria should be listed in the Acknowledgements section with their specific contributions described (e.g., "provided technical editing," "collected data," "acquired funding") [34]. Remember to obtain written permission from acknowledged individuals [34].

Q12: What is the policy on using Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools? AI tools (like LLMs) cannot be listed as authors [34]. Any use of AI-assisted technology for writing assistance, data analysis, or figure generation must be explicitly disclosed in the manuscript, typically in the methods or acknowledgement section. Authors are solely responsible for the accuracy, integrity, and originality of the content, including any parts generated by AI [34].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Creating a Collaborative Authorship Plan

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for establishing a robust and dispute-free authorship plan for a research project.

1. Initial Team Meeting (Project Inception)

- Objective: Align the entire team on authorship expectations.

- Methods: Convene a meeting with all key stakeholders (PIs, co-investigators, statisticians, researchers, etc.) [37]. Discuss and agree upon:

2. Drafting the Written Agreement

- Objective: Create a formal record of the decisions made.

- Methods: A written document should be created and circulated. It must include [37]:

- The specific authorship criteria.

- A preliminary contributor roles and responsibility matrix.

- The agreed-upon process for determining author order.

- A protocol for handling changes in contribution or authorship.

3. Implementation and Ongoing Monitoring

- Objective: Ensure the plan remains relevant as the project evolves.

- Methods:

- Maintain the Contribution Matrix: Regularly update the matrix (see Table above) as the project progresses [37].

- Schedule Check-in Meetings: Periodically revisit the authorship agreement during project meetings to confirm it still reflects reality and make adjustments as needed [36].

- Pre-Submission Verification: Before manuscript submission, confirm that every listed author meets all criteria and has approved the final version [35].

The following workflow diagram visualizes this multi-stage protocol for creating a collaborative authorship plan:

Protocol 2: Authorship Dispute Resolution Pathway

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to resolving authorship disputes, from informal discussion to formal escalation.

1. Informal Resolution

- Objective: Resolve the conflict at the lowest level.

- Methods:

2. Facilitated Mediation

- Objective: Achieve resolution with impartial guidance.

- Methods: If informal talks fail, involve an impartial third party, such as a mediator or the institution's Research Governance office [37] [36]. The mediator facilitates discussion to help parties reach a mutually acceptable agreement.

3. Formal Institutional Review

- Objective: A final adjudication for unresolvable disputes.

- Methods:

The sequence diagram below illustrates the formal dispute resolution process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key "reagents" for conducting a successful collaboration, focusing on documentation and agreement tools rather than laboratory supplies.

Table: Essential Tools for a Collaborative Authorship Plan

| Tool | Function | Key Features / Components |

|---|---|---|

| ICMJE Authorship Criteria | Provides the definitive, internationally recognized standard for qualifying as an author. | Serves as the benchmark for all authorship discussions. The four criteria ensure substantive contribution, intellectual input, approval, and accountability [34]. |

| Written Authorship Agreement | A living document that formalizes the team's decisions and serves as a reference point. | Should outline authorship criteria, roles, author order rationale, and a change-management process [37]. |

| Contribution Matrix | An objective tracking tool to document and quantify each member's input throughout the project lifecycle. | A table (e.g., with rows for team members and columns for project phases) that is updated regularly to provide a clear record of contributions [37]. |

| Institutional Policy Documents | Guidance and official procedures provided by the researchers' host institution(s). | Defines the local definition of authorship, outlines processes for dispute resolution, and provides contacts for research ethics and governance support [36]. |

| Authorship Verification Software | Tools used to confirm the originality of written work and detect potential ghostwriting. | Uses stylometry (writing style analysis) to compare a submitted document against a researcher's previous work, helping to identify undisclosed contributors [38]. |

| 4-iodo-N-(4-methyl-1-naphthyl)benzamide | 4-iodo-N-(4-methyl-1-naphthyl)benzamide | 4-iodo-N-(4-methyl-1-naphthyl)benzamide is a high-purity benzamide derivative for research use only (RUO). It is not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

| GY1-22 | GY1-22|DNAJA1-mutP53 Inhibitor|326903-84-8 | GY1-22 is a small molecule inhibitor that targets the DNAJA1-mutP53R175H interaction, for cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Why is properly acknowledging contributors important?

Properly acknowledging individuals who do not meet the full criteria for authorship is a critical practice in ethical research publishing. It ensures transparency, fairly recognizes all contributions to a research project, and helps maintain the integrity of the authorship process by clearly distinguishing between authors and other contributors [1] [39].

Failing to properly acknowledge contributors, or inappropriately including non-authors in the author list (known as gift, guest, or ghost authorship), distorts the true record of contributions, misleads readers and reviewers, and can unfairly impact researchers' careers [1] [40]. Most scientific journals, including Science and Nature, endorse the practice of using the acknowledgments section for this purpose [1].

Who qualifies for acknowledgment versus authorship?

Authorship Criteria

According to widely accepted guidelines, such as those from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), an author must meet all of the following criteria [39] [40]:

- Make substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Draft the work or review it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Give final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments Criteria

Contributors who do not meet all of the above criteria should not be listed as authors. Instead, their efforts should be recognized in the acknowledgments section [39]. The following table summarizes activities that typically warrant acknowledgment rather than authorship.

Table 1: Contributions for Acknowledgments vs. Authorship

| Category | Examples of Contributions that Belong in Acknowledgments | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Financial & Administrative | Acquisition of funding; General supervision of a research group; General administrative support [39] [40]. | While vital, these activities alone do not constitute a substantive intellectual contribution to the work itself. |

| Technical & Support Services | Technical assistance in data collection or providing materials without intellectual contribution; Writing assistance, technical editing, language editing, and proofreading [1] [39]. | These are supportive roles that do not typically involve the core intellectual work of designing the study or interpreting the data. |

| Advisory & Feedback | A supervisor or senior researcher who provided valuable feedback or general guidance; A colleague who provided specific, non-core help (e.g., with illustrations) [1]. | Valuable feedback alone does not reach the threshold of "critical revision for important intellectual content" required for authorship. |

How should I write an effective acknowledgments section?

An effective acknowledgments section is clear, specific, and concise.

- Be Specific: Clearly state the contribution of each person or group. Avoid vague language [1].

- Use Simple Statements: Directly describe what each person or entity did.

- Follow Journal Guidelines: Always check your target journal's "Instructions for Authors" for any specific requirements regarding the acknowledgments section [1].

Examples of effective acknowledgment statements:

- "The authors thank [Full Name] of [Company/Institution] for providing editorial and proofreading support." [1]

- "The authors are grateful to [Full Name] for their valuable comments on improving this manuscript." [1]