From Hippocrates to CRISPR: The Historical Development of Christian Bioethics in Medicine and Research

This article traces the historical development of Christian bioethics from its roots in Graeco-Roman medical traditions to its modern engagement with biotechnology and drug development.

From Hippocrates to CRISPR: The Historical Development of Christian Bioethics in Medicine and Research

Abstract

This article traces the historical development of Christian bioethics from its roots in Graeco-Roman medical traditions to its modern engagement with biotechnology and drug development. It explores the foundational theological principles, such as the sanctity of life and imago Dei, that have shaped Christian moral reasoning in medicine. The content provides a methodological framework for applying this tradition to contemporary issues, including reproductive technologies, end-of-life care, and genetic engineering. It also addresses current challenges like secularization and technological acceleration, offering troubleshooting insights for researchers and clinicians. Finally, it compares Christian perspectives with secular bioethical frameworks, validating the distinct contributions and ongoing relevance of a theologically informed approach to biomedical science.

From Antiquity to Modernity: Tracing the Theological and Historical Roots of Christian Bioethics

The historical development of Christian bioethics, while distinctive in its theological conclusions, did not emerge in a vacuum. Its foundational bedrock was laid through a complex interplay of Graeco-Roman and Early Jewish precedents, which first established the principle that medical practice must be governed by a moral framework deeply infused with religious conviction. The Hippocratic Oath, originating from the Greek island of Kos in the 5th to 3rd centuries BC, represents the most seminal and systematic expression of this integration in the Western tradition [1]. This oath, though a product of its polytheistic context, established enduring ethical pillars—beneficence, non-maleficence, and confidentiality—that would transcend its original setting [2] [3]. Simultaneously, Jewish medical thought, as reflected in texts like the Book of Sirach, developed a parallel tradition that respected medical skill while subsuming it under a monotheistic understanding of God as the ultimate healer [4]. This article examines these twin pillars, analyzing their core ethical tenets and demonstrating how they created a syntheses of spiritual morality and clinical practice that would later provide the essential raw material for the development of specifically Christian bioethics.

The Hippocratic Oath: A Graeco-Roman Ethical Framework

Historical Context and Core Content

The Hippocratic Oath is arguably the most well-known text of the Hippocratic Corpus, though modern scholars generally do not attribute it directly to Hippocrates himself, estimating its composition to the fourth or fifth century BC [1]. It functioned as a vow taken by new physicians, swearing by deities including Apollo, Asclepius, Hygieia, and Panacea to uphold specific ethical standards [1] [3]. Its purpose was to define the medical profession, setting it apart from mere craft and establishing a moral community bound by shared principles [3] [4].

Table 1: Key Ethical Directives in the Original Hippocratic Oath

| Ethical Directive | Original Text Example (Translation) | Modern Ethical Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Beneficence & Non-Maleficence | "I will use treatment to help the sick... but I will never use it to injure or wrong them." [2] | Beneficence, Non-maleficence |

| Prohibition of Euthanasia | "I will not give a deadly drug to anybody though asked to do so, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect." [1] [2] | Sanctity of Life |

| Prohibition of Abortion | "Similarly I will not give a pessary to a woman to cause abortion." [1] [2] | Sanctity of Life |

| Confidentiality | "Whatsoever I shall see or hear in the course of my profession... I will never divulge, holding such things to be holy secrets." [1] | Confidentiality, Privacy |

| Sexual Integrity | "I will keep myself free from... fornication with woman or man, bond or free." [2] | Professional Boundaries |

| Respect for Teachers | "To hold him who taught me this art as equal to my parents..." [1] | Professional Guild Loyalty |

Religious and Philosophical Underpinnings

The Oath's framework, while containing pragmatic professional guidelines, was deeply embedded in a religious worldview. The invocation of Apollo (god of healing and plagues) and Asclepius (demigod of medicine) was not merely ceremonial; it called upon these deities as witnesses, placing the oath-taker's life and career under divine scrutiny [1] [3]. The promise to guard one's life and art "in purity and holiness" further underscores the sacred character assigned to the medical vocation [1]. This heavily religious tone distinguishes the Oath from other, more secular, texts in the Hippocratic Corpus [1].

The Oath can also be understood as a proactive solution to the essential moral dilemma of medicine: the healer's capacity to wound. As Cavanaugh argues, the foundational problem of medicine is "healers wounding," given that therapeutic interventions often involve inherent harm (e.g., surgery, side effects of drugs) [3]. The Oath serves as a public promise that the physician will not engage in intentional harm or "role conflation," where the healer becomes a wounder for purposes like assassination, abuse, or social engineering [3].

Table 2: Interpretation of Key Ethical Prohibitions in the Hippocratic Oath

| Prohibition | Historical Context & Interpretation | Modern Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Euthanasia | Possibly aimed at preventing physicians from being used as political assassins, as well as rejecting mercy killing. Accounts exist of ancient physicians assisting suicides, suggesting the Oath was not universally followed on this point [1]. | Central to debates on physician-assisted suicide and the role of medicine in ending life [5]. |

| Abortion | Debate existed even in antiquity; some practitioners saw it as a blanket ban, while others, like Soranus, believed it was permissible for the mother's health. The specification of "pessary" led to debate on whether other methods were allowed [1]. | Remains a highly controversial issue in medical ethics, with many modern oaths omitting the explicit prohibition [1] [5]. |

| Surgery | "I will not use the knife, not even on sufferers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of such as are engaged in this work." This likely reflects a guild division between physicians and surgeons, acknowledging limits of expertise [1] [3]. | Underpins modern concepts of specialization and referral, and the ethical duty to practice within one's scope of competence. |

Early Jewish Medical Ethics: A Monotheistic Integration

Alongside the Graeco-Roman tradition, Early Jewish thought developed a distinct approach to integrating faith and medicine. Unlike the Hippocratic model, which created a separate professional guild with its own oath, Jewish ethics embedded medical practice within the broader religious and moral framework of the Torah and wisdom literature.

The core principle underpinning Jewish medical ethics is pikuach nefesh—the obligation to save a human life, which overrides almost all other religious commandments [6]. This established healing as a supreme religious duty. The Book of Sirach (circa 2nd century BCE), a text from the Hellenistic period, provides a clear window into this synthesis. It states: "Hold the physician in honor, for he is essential to you, and God it was who established his profession. From God the doctor has his wisdom... God's creative work makes the doctor necessary... Then let the doctor take over—for God created him too—and do not let him leave you, for you need him." [4]

This passage demonstrates a nuanced view: God is the ultimate healer and source of medical wisdom, but the human physician, endowed by God with knowledge and skill, is an essential instrument in the divine plan for healing [4]. The physician is called "distinguished" and admired among the great for applying skills with personal integrity shaped by religious devotion [4]. This framework allowed for a positive regard for professional medicine while maintaining theological consistency.

Comparative Analysis: Synthesizing the Precedents

The Graeco-Roman and Early Jewish traditions, while theologically distinct, shared crucial similarities that would make them amenable to later Christian adoption and adaptation. Both traditions rejected a purely mechanistic view of the body and healing, insisting that medicine was a moral enterprise.

Table 3: Comparison of Graeco-Roman and Early Jewish Medical Ethical Precedents

| Aspect | Graeco-Roman (Hippocratic) Precedent | Early Jewish Precedent |

|---|---|---|

| Theological Foundation | Polytheistic; oath sworn to Apollo, Asclepius, and other healing deities [1]. | Monotheistic; healing power ultimately resides with the God of Israel [4]. |

| Role of the Physician | Member of a sworn professional guild; a technician who upholds a sacred art [1] [3]. | A skilled and honored craftsman whose ability is granted by God; an instrument of divine will [4]. |

| Core Ethical Principles | Non-maleficence ("do no harm"), confidentiality, prohibitions on abortion/euthanasia [1] [7]. | Preservation of life (pikuach nefesh), compassion, the physician's duty to heal [6] [4]. |

| Concept of the Body | The body was a natural system (humors), but the Oath imbued it with moral inviolability [1]. | The body is created by God and belongs to Him; human beings are stewards of their own bodies [4]. |

| Primary Motivation | Professional integrity, honor among men, fear of divine retribution from the oath's gods [1]. | Religious duty to save life and alleviate suffering, in obedience to God's law [6]. |

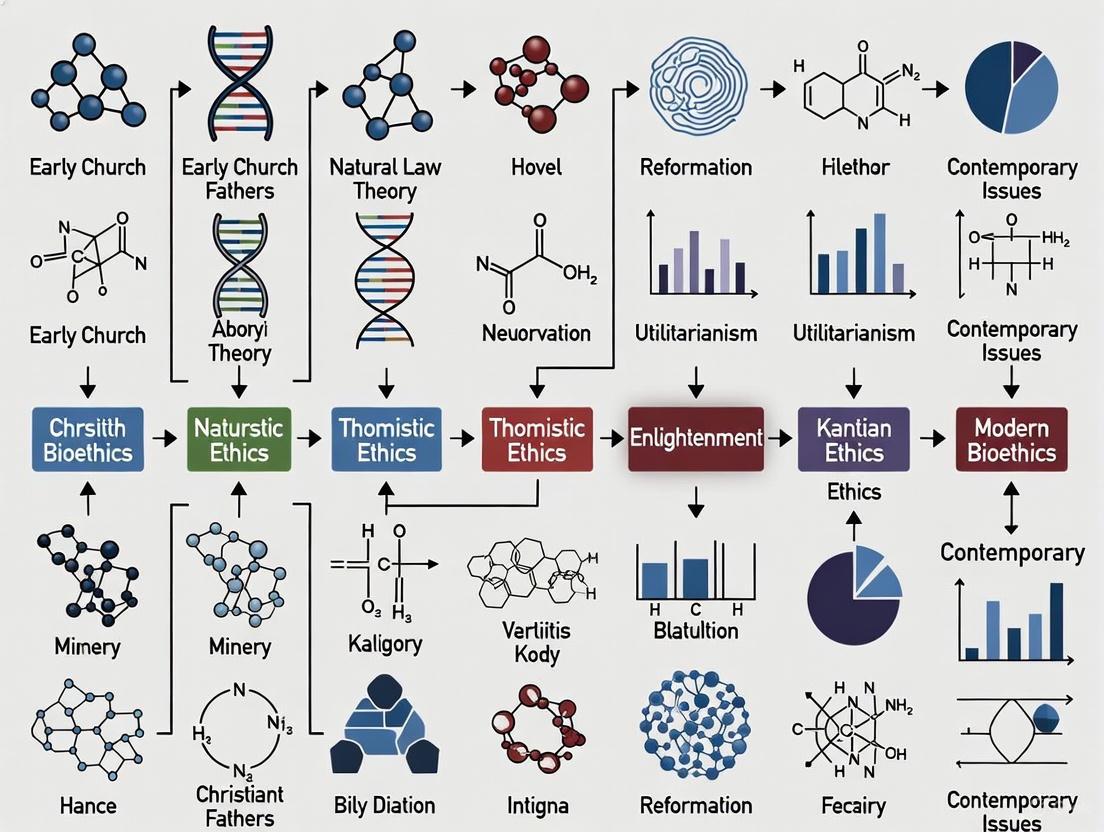

The flowchart below illustrates the conceptual relationship and historical influence of these precedents on later Christian bioethics.

Conceptual Synthesis of Precedents

Methodological Toolkit for Historical-Ethical Research

Research in historical medical ethics requires a distinct set of methodological tools and conceptual frameworks. Unlike laboratory science, the "reagents" are textual and philosophical sources, and the "protocols" are methods of historical and ethical analysis.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Historical-Bioethical Analysis

| Research 'Reagent' (Source/Concept) | Function in Analysis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Textual Editions | Provide authoritative versions of ancient texts, with variant readings and historical context. | Using the 1923 Loeb edition or Francis Adams' translation of the Hippocratic Oath for accurate primary source analysis [1] [7]. |

| Historical Contextualization | Situates ethical texts within their specific societal, political, and religious milieu to avoid anachronism. | Understanding the Hippocratic Oath's prohibitions in light of Greek cultic practices and guild structures, or Sirach in the context of Hellenistic Judaism [1] [4]. |

| Philosophical Frameworks | Provides lenses (e.g., virtue ethics, deontology) to systematically analyze the moral structure of historical texts. | Interpreting the Hippocratic Oath not as a set of rules but as a description of the virtuous physician, emphasizing character and intent [3]. |

| Comparative Religious Analysis | Identifies parallels and divergences between different religious traditions' approaches to similar ethical dilemmas. | Juxtaposing the Hippocratic Oath with the Oath of Asaph (Jewish) or later Islamic medical vows to identify shared cross-cultural values [2] [6]. |

| Reception History | Traces the interpretation and influence of a text (e.g., the Oath) through different historical periods and cultures. | Examining how early Christian writers like Jerome and Gregory of Nazianzus adopted or critiqued the Hippocratic Oath [4]. |

Analytical Protocol: Tracing an Ethical Principle

A core methodological protocol in this field involves tracing the development of a specific ethical principle from its pre-Christian origins into early Christian thought.

- Source Identification: Locate the primary textual sources for the principle in both Graeco-Roman and Early Jewish traditions. For example, the principle of confidentiality is explicitly stated in the Hippocratic Oath: "Whatever I may see or hear in the lives of my patients... I will keep to myself" [1]. In Jewish tradition, while not explicitly outlined in a medical oath, it is derived from broader principles of guarding secrets and avoiding gossip (lashon hara).

- Conceptual Mapping: Analyze the justification and scope of the principle in each tradition. In the Hippocratic Oath, confidentiality is tied to what is "shameful to be spoken," treating patient information as "holy secrets" [1] [3]. In Jewish thought, it would be framed as a duty to protect a neighbor's dignity and privacy.

- Synthesis Point Analysis: Identify how the two streams were synthesized by early Christian thinkers. For instance, early Christian physicians adopted the Oath's strict confidentiality rule but within a monotheistic framework, seeing the body and its secrets as part of God's creation, thus making violation of confidence a sin against God and neighbor [5] [4].

- Outcome Assessment: Evaluate the resulting Christian ethical position. The synthesis led to a robust, theologically grounded commitment to patient privacy that became a cornerstone of Western medical ethics, later codified in Christian medical guilds and institutions [4].

The Graeco-Roman and Early Jewish traditions provided the indispensable raw material for the subsequent development of Christian bioethics. The Hippocratic Oath established a durable framework of professional virtue, patient-centered duties, and sacred boundaries, all undergirded by a religious conception of the medical art [1] [3]. Simultaneously, Early Jewish ethics embedded the practice of medicine within a monotheistic worldview, establishing the duty to heal and affirming the physician as a legitimate, God-endowed agent of care [6] [4]. Together, these precedents established a powerful synthesis of religious morality and medical practice, creating a legacy that would be adopted, debated, and transformed by Christian theologians and physicians for centuries to come. The critical engagement of early Christian writers like Jerome with the Hippocratic tradition demonstrates that this was not a simple adoption but a dynamic process of critical reception, setting a pattern for the ongoing dialogue between faith, ethics, and medicine that continues to shape bioethical discourse today [4].

The integration of classical medical knowledge with Christian theology during the early centuries of the Church represents a critical transformation in the history of medicine and bioethics. This synthesis created a distinct framework for healthcare that valued empirical practice while reorienting its purpose toward charity, witness, and divine grace. Figures such as Saints Cosmas and Damian, and Luke the Evangelist, embody this synthesis, demonstrating how early Christians adopted the technical medical knowledge of the Greco-Roman world while fundamentally transforming its ethical foundations through a theological lens. This historical development established foundational principles that continue to inform Christian bioethics research, particularly in its approach to healing, the patient-practitioner relationship, and the integration of faith and reason.

Historical and Theological Context

The Classical Medical Landscape

In the 3rd to 4th centuries CE, medicine was largely based on trial and error with substances derived from the animal, plant, and mineral kingdoms [8]. Surgical approaches, as gleaned from surviving instruments and texts, were characterized by cutting, scraping, and probing [8]. Most medical lore of the era was deeply grounded in religious belief, with both the causes of illness and successful treatments widely ascribed to the acts of gods or God [8]. This created a fertile environment for the integration of medical practice with Christian theology.

The region of Antioch, a crossroads of Western civilization during these early centuries, served as a literal and figurative nexus for this synthesis [8]. Founded in 293 BC in ancient northern Syria (now southern Turkey), this region hosted multiple cultures and religions and produced at least four patron saints of medicine, including Cosmas, Damian, Luke the Apostle, and Saint Panteleimon [8]. The route between Antioch and Rome witnessed the emergence of a distinctly Christian approach to medicine that would influence healthcare for centuries.

Foundations of Christian Medical Ethics

Early Christian medical ethics emerged from several key theological principles that transformed classical approaches:

- The Imago Dei: The concept that all humans are created in God's image established the inherent dignity of every patient.

- Kenotic Service: The self-emptying model of Christ informed the concept of service without expectation of reward.

- Sacramental Worldview: The physical world, including the human body, was viewed as a vehicle of divine grace.

- Charity as Mandate: Healing was understood as fulfilling Christ's command to love one's neighbor.

These principles created what would later be articulated as the Unmercenary Physician ideal (in Greek, anargyroi or "without silver"), who healed purely out of love for God and humanity, strictly observing Christ's command: "Freely you have received, freely give" (Matthew 10:8) [9] [10].

Case Studies in Early Christian Medical Synthesis

Saints Cosmas and Damian: The Unmercenary Ideal

Saints Cosmas and Damian were Arabian twins, born of devoutly Christian parents around 270 CE [8] [9]. They grew up with three other brothers in Aegeae, a small town between Turkey and Syria on the route from Antioch to Tarsus [8]. Following their medical studies in Antioch, they returned to Aegeae to practice medicine and proselytize [8]. Historical accounts consistently depict them holding boxes, tubes, or vessels associated with medications, symbols that later became associated with the medical and pharmaceutical professions [8].

Medical Practice and Innovations

As physicians, Cosmas and Damian never accepted payment for their services, earning them the title anargyroi (Greek for "without silver") [8] [9]. Their practice addressed a wide range of conditions, including:

- Infectious diseases: tuberculosis, malaria, typhus, and diphtheria [8]

- Surgical conditions: wounds, fractures, and dislocations [8]

- Chronic conditions: blindness, paralysis [9]

Their therapeutic approaches combined traditional methods like blood-letting with spiritual practices including prayer and incubation (where the sick would move into churches or sanctuaries to be closer to God) [8]. According to 15th-century Italian physician Saladino d'Ascoli, the medieval electuary known as opopira—a complex compound medicine used to treat paralysis and other maladies—was invented by Cosmas and Damian [9] [10]. This medication contained approximately 70 ingredients, including opium, mandrake, henbane, fragrant roots, resin, herbs, and honey, usually administered mixed with wine [10].

Table 1: Medical Practices of Saints Cosmas and Damian

| Medical Aspect | Description | Theological Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Payment Policy | Never accepted payment for services | Embodied Christ's command: "Freely you have received; freely give" (Matthew 10:8) |

| Treatment Modalities | Combined herbal remedies, surgery, blood-letting with prayer and spiritual guidance | Viewed healing as both physical and spiritual process |

| Pharmacological Innovation | Developed opopira electuary with 70+ ingredients | Understood material creation as gift for healing |

| Patient Selection | Treated all regardless of faith or status | Reflected God's universal love and compassion |

The Miracle of the Black Leg: An Early Transplantation Narrative

The most famous account of Cosmas and Damian's medical prowess is the "miracle of the black leg"—a posthumous miracle reportedly occurring hundreds of years after their martyrdom [8] [9]. According to legend, a devout deacon named Justinian who worked in the Saints' Basilica on the outskirts of Rome developed a gangrenous or cancerous leg [8]. During incubation in the church, he experienced a dream where Cosmas and Damian appeared and amputated his diseased limb, replacing it with the leg of a recently deceased Ethiopian man [8] [9].

Upon awakening, the deacon discovered his body intact, free of disease, but with the dark-skinned limb attached [8]. When people checked the Ethiopian donor's tomb, they found the deacon's original white leg attached to the deceased man's body [9]. This story, documented in the Golden Legend and depicted in numerous artistic works, represents an early narrative of transplantation and raises profound questions about bodily integrity, race, and divine healing that continue to resonate in contemporary bioethics [9].

Martyrdom and Legacy

During the persecution under Emperor Diocletian, Cosmas and Damian were arrested by the Prefect of Cilicia, Lysias, for refusing to renounce their faith [8] [9]. According to tradition, they survived multiple execution attempts—including crucifixion, stoning, and being pierced by arrows—before ultimately being beheaded alongside their three brothers [8] [9]. Their martyrdom cemented their status as Christian witnesses who applied their medical skills as an expression of faith rather than professional advancement.

Their legacy includes:

- Patronage of physicians, surgeons, pharmacists, and dentists [9]

- Dedicated churches throughout the Middle East, Europe, and North America [8]

- Feast days on September 26 (Catholic Church), September 27 (pre-1970 calendar), and November 1 (Eastern Orthodox) [9]

- Relics venerated across Europe, including in Madrid, Munich, and Vienna [9]

Saint Luke the Evangelist: Physician and Historian

While less information is available in the search results specifically addressing St. Luke's medical practice, he is traditionally known as the "beloved physician" (Colossians 4:14) and is commonly regarded as a patron saint of physicians [10]. His detailed accounts of healing miracles in the Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles demonstrate a particular interest in medical themes, suggesting his medical background informed his theological narrative.

Analysis of the Early Christian Synthesis

Theological Transformation of Medical Practice

The early Christian approach to medicine represented both continuity and discontinuity with classical traditions:

Table 2: Transformation of Medical Practice through Christian Theology

| Classical Medicine Element | Christian Adoption & Transformation |

|---|---|

| Empirical Observation | Retained but understood within framework of God's created order |

| Herbal & Mineral Remedies | Adopted but accompanied by prayer for divine efficacy |

| Professional Fees | Rejected in favor of charitable service |

| Disease Etiology | Acknowledged physical causes while recognizing spiritual dimensions |

| Healer Authority | Shifted from technical expertise to God as ultimate healer |

This synthesis created a distinctively Christian medical ethos characterized by:

- Therapeutic Orientation: Healing as participation in God's restorative work

- Kenotic Practice: Medicine as self-emptying service rather than profession

- Sacramental Approach: The body as temple of the Holy Spirit requiring reverent care

- Eschatological Perspective: Healing as foretaste of complete restoration in Kingdom of God

Methodological Framework for Historical Research

Research Reagent Solutions for Historical-Bioethical Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Framework for Historical Christian Bioethics

| Research Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Textual Analysis | Critical examination of primary sources (hagiographies, liturgical texts, artistic depictions) | Analyzing variations in "Miracle of the Black Leg" narratives across traditions [8] [9] |

| Historical Contextualization | Situating medical practices within broader cultural, political, and theological developments | Examining Cosmas & Damian's practice within Diocletian persecutions [8] |

| Conceptual Mapping | Tracing evolution of key bioethical concepts (dignity, charity, vocation) | Tracking anargyroi ideal from early Church to contemporary bioethics [9] [10] |

| Comparative Analysis | Identifying continuities and discontinuities with classical and other religious medical traditions | Contrasting Christian incubation with Asklepian temple healing [8] |

Experimental Protocol for Analyzing Historical Medical Ethics

Protocol Title: Multidimensional Analysis of Early Christian Medical Synthesis

Research Question: How did early Christians adopt and transform classical medical knowledge through theological frameworks?

Methodology:

Source Identification and Validation

- Collect hagiographical texts, liturgical materials, and artistic depictions

- Apply source criticism to establish reliability and historical context

- Identify theological motifs and their integration with medical content

Conceptual Mapping

- Extract key medical ethical principles from primary sources

- Map relationships between theological concepts and medical practices

- Trace historical development of identified principles

Comparative Analysis

- Compare Christian approaches with contemporary classical medical texts

- Identify distinctive features of Christian medical synthesis

- Analyze regional variations in medical-theological integration

Contemporary Relevance Assessment

- Evaluate potential applications to modern bioethical challenges

- Identify continuities in Christian medical ethics

- Formulate conceptual frameworks for contemporary practice

Visualizing the Early Christian Medical Synthesis

Theological Foundations of Early Christian Medicine

Integration of Classical and Christian Medical Elements

The early Christian synthesis of classical medicine through a theological lens established foundational principles that continue to inform Christian bioethics research and practice. The model of Saints Cosmas and Damian—combining technical medical skill with selfless service oriented toward divine grace—represents a significant development in the history of medicine that transformed the healer-patient relationship and established medicine as a vocation rather than merely a profession.

This historical analysis reveals three key insights for contemporary Christian bioethics:

- Integration of Faith and Reason: The early Christian approach refused to dichotomize empirical medical knowledge and theological truth, instead viewing them as complementary aspects of a unified reality.

- Medicine as Kenotic Service: The anargyroi ideal challenges contemporary commodification of healthcare, presenting an alternative model grounded in self-giving love.

- Theological Framing of Medical Ethics: Early Christians demonstrated how medical practice could be reoriented through theological concepts like creation, incarnation, and eschatological hope.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this historical framework offers resources for considering how technological advances might be shaped by theological understandings of human dignity, the common good, and service to the most vulnerable. The early Christian synthesis provides not merely historical context but a conceptual framework for developing a distinctively Christian approach to contemporary bioethical challenges that remains grounded in both scientific excellence and theological wisdom.

The medieval period was a formative era in the history of Western medicine and bioethics, establishing intellectual and institutional frameworks that would endure for centuries. This epoch was characterized by the synergistic integration of classical medical knowledge, religious care practices, and emerging ethical philosophy. The convergence of these elements created a unique foundation for what would later evolve into systematic bioethical thought. Within the context of Christian tradition, the preservation and transmission of Galenic medical theories through monastic institutions, coupled with the scholastic development of natural law theory, created a coherent system for understanding the human body, disease, and moral responsibility. This article examines these three pivotal developments—Galenic medicine, monastic care, and natural law theory—as essential precursors to contemporary Christian bioethics, providing researchers and healthcare professionals with historical context for modern ethical frameworks.

The Dominance of Galenic Medicine

Core Principles and Theoretical Framework

The medical system of Galen of Pergamon (129–216 CE) became the dominant paradigm in Western medicine for nearly 1,500 years, largely through its alignment with medieval Christian thought. Galen's approach was systematized around several core principles that would define medical practice and theory throughout the medieval period [11].

Central to Galenic medicine was the humoral theory, which posited that the human body contained four fundamental liquids or "humors": phlegm, blood, yellow bile, and black bile. Health was understood as the proper balance of these humors, while disease resulted from their imbalance [11]. This theoretical framework dictated diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for centuries, with physicians employing techniques like bloodletting and purgatives to correct perceived humoral excesses [11].

Galen's work frequently referenced a divine rationality evident in the human body's design, a concept that resonated deeply with medieval Christian theology [12]. His monotheistic beliefs, unusual for a Roman of his time, aligned with early Christian views and facilitated the Church's eventual endorsement of his medical system [12]. This compatibility would prove crucial to the preservation and transmission of Galenic thought following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

Institutional Endorsement and Transmission

The enduring influence of Galenic medicine can be largely attributed to its institutional adoption by the Christian Church. During the European Dark Ages, when much classical knowledge was lost in the West, monasteries became the primary centers for preserving and studying Galenic texts [12]. The Church's endorsement provided Galen's theories with an authority that remained largely unchallenged until the Renaissance [11].

Table: Key Factors in the Church's Endorsement of Galenic Medicine

| Factor | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Theological Compatibility | Galen's monotheism and concept of divine design in the human body | Alignment with Christian creation theology and moral framework |

| Institutional Preservation | Monastic copying and study of Galenic texts | Ensured continuity of medical knowledge during cultural instability |

| Educational Integration | Incorporation into medieval university curricula | Established Galenism as authoritative medical science for centuries |

| Philosophical Consistency | Compatibility with Aristotelian philosophy favored by Scholastics | Allowed integration into comprehensive theological worldview |

The scholastic integration of Galenism into medieval university education, particularly through the work of theologians like Thomas Aquinas, further solidified its authority [12]. This institutional support meant that Galenic theories persisted even as more advanced medical knowledge developed, only facing substantial challenge during the Renaissance with figures like Andreas Vesalius and William Harvey [11] [12].

Monastic Medicine: Institutionalizing Care

Foundations and Infrastructure

Monastic institutions developed into comprehensive medical centers during the medieval period, creating an enduring model for integrated patient care. The philosophical foundation for this system derived from the Benedictine Rule, which instructed that "before all things and above all things care is to be had of the sick, that he be served in very deed as Christ Himself" [13]. This theological framing positioned healthcare as both a spiritual and practical obligation.

Monasteries established sophisticated medical infrastructures that integrated therapeutic spaces with religious life. The ninth-century plan of St. Gall monastery in Switzerland exemplifies this approach, featuring a dedicated House of Physicians, medicinal herb garden, House for Bloodletting, and a large Monk's Infirmary [13]. These facilities were strategically positioned within the monastic complex, with the physician's house adjacent to key therapeutic spaces and the kitchens, demonstrating thoughtful consideration of both clinical efficacy and patient comfort [13].

The conceptual integration of physical and spiritual health is vividly illustrated in manuscripts like National Library of Medicine MS E8 from Bury St Edmunds Abbey, which combines medical recipes with miracle stories and hymns to the Virgin Mary [14]. This combination provided monastic practitioners with resources for addressing both bodily ailments and spiritual concerns, reflecting a holistic understanding of health that characterized the monastic approach.

Practical Applications and Historical Significance

Monastic medicine balanced traditional herbal knowledge with emerging clinical practices. The herb garden at St. Gall contained sixteen different medicinal plants that, along with vegetables and orchards, provided materials for poultices, purges, and infusions [13]. Monasteries also maintained extensive medical libraries that preserved and transmitted classical knowledge, training monk-practitioners and serving as resources for theological and philosophical writers [13].

Table: Monastic Medical Infrastructure at St. Gall (9th Century)

| Facility | Function | Design Features |

|---|---|---|

| Monk's Infirmary | Primary care for sick brethren | Separate from laity facilities; integrated into complex |

| House of Physicians | Residence and practice space for physicians | Adjacent to key therapeutic areas and kitchens |

| House for Bloodletting | Phlebotomy procedures | Multiple fireplaces for patient warmth during recovery |

| Medicinal Herb Garden | Cultivation of therapeutic plants | Sixteen specific medicinal species; near vegetable gardens |

The regulatory landscape for monastic medicine evolved throughout the medieval period. The Second Lateran Council of 1139 prohibited "monks and canons regular" from practicing medicine "with a view to temporal gain," creating a distinction between care for the body and care for the soul that continues to influence modern healthcare [13]. Despite this regulation, the original ideal of brethren caring for their own health remained fundamental to monastic communities throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance [13].

Natural Law Theory: Ethical Foundations

Philosophical Development and Key Concepts

The scholastic engagement with natural law theory provided a crucial ethical framework that would later inform systematic bioethical reasoning. Natural law theory posits the existence of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles discoverable through reason [15]. This concept, with origins in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, was systematically developed within medieval Christian thought, particularly by Thomas Aquinas, who synthesized classical philosophy with Christian theology [15].

Aquinas argued that because human beings possess reason—understood as a spark of the divine—all human lives are sacred and of infinite value compared to any other created object [15]. This foundation established the principle of fundamental human equality and intrinsic basic rights that could not be removed [15]. The theological integration of natural law positioned it as a universal moral standard accessible to all people through reason, while being consistent with Christian revelation.

The conceptual relationship between natural law and conscience was a significant development in medieval moral psychology. Conscience (conscientia) was understood as the mental faculty that applies general moral principles to specific situations [16]. The Apostle Paul contributed significantly to this understanding, describing how Gentiles, though without Mosaic law, "do by nature things required by the law" because its requirements are "written on their hearts, their consciences also bearing witness" [16].

Structural Framework and Moral Application

The systematic formulation of natural law theory by Aquinas established a hierarchical understanding of law that would profoundly influence Western ethical traditions. According to this framework, natural law participates in the eternal law of God but is accessible through human reason [15]. This provided a foundation for moral reasoning that integrated theological and philosophical approaches.

The operational mechanism of natural law in moral decision-making involved the interplay between synderesis (the understanding of fundamental moral principles) and conscientia (the application of these principles to specific cases) [16]. This distinction allowed medieval philosophers to account for both the universal accessibility of moral truths and the potential for erroneous moral judgments in particular situations.

Table: Medieval Development of Conscience and Natural Law Concepts

| Concept | Origin | Function | Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Law (lex naturalis) | Cicero, Stoic philosophy | Objective moral standard based on nature | Christianized by Aquinas; foundation of universal morality |

| Synderesis | Jerome's commentary on Ezekiel | Habit of understanding fundamental moral principles | Philosophical distinction for intuitive grasp of first principles |

| Conscience (conscientia) | Greek playwrights; Pauline epistles | Application of principles to specific cases | Understood as subjective norm implementing objective natural law |

The ethical implications of natural law theory extended to medicine through the concept of the body's divine design and purpose. This framework provided a basis for evaluating medical practices according to their conformity with natural ends and purposes, establishing precedents that would later inform Catholic bioethical positions on issues ranging from surgical ethics to end-of-life care.

Synthesis and Interconnections

Conceptual and Practical Integration

The three foundational developments of Galenic medicine, monastic care, and natural law theory formed an integrated system of thought and practice in the medieval period. The theoretical framework of Galenic medicine provided a comprehensive understanding of human physiology and pathology; monastic institutions created practical structures for delivering care informed by Christian values; and natural law theory established ethical principles for guiding medical practice and moral reasoning.

The structural relationship between these elements can be visualized through their functional connections:

This conceptual integration created a coherent worldview in which medical theory, clinical practice, and ethical reasoning mutually informed one another within a overarching theological framework. The body was understood as a divine creation whose functioning could be comprehended through Galenic theory, whose care was a spiritual duty institutionalized in monastic practice, and whose treatment was guided by ethical principles accessible through natural law.

Knowledge Preservation and Transmission

The scholastic methodology of reconciling classical medical knowledge with Christian theology enabled the preservation and transmission of Galenic medicine while situating it within a morally and theologically acceptable framework. Monastic scriptoria played a crucial role in this process, copying and preserving medical manuscripts alongside religious texts [13]. The Abbey of Bury St Edmunds in England, for instance, became a renowned center for medical learning, with manuscripts containing dozens of medical texts alongside religious materials [14].

The intellectual synthesis achieved by figures like Constantine the African, who translated Arabic medical texts at the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, demonstrates how monastic institutions facilitated the cross-cultural transmission of medical knowledge [13]. Constantine's work incorporated Arabic medical advancements while adapting them to the moral context of monastic life, as seen in his modification of treatments for "the burden of eros" to align with monastic celibacy [13].

Research Tools and Methodologies

Analytical Framework for Historical Research

Contemporary research into medieval medical and ethical developments requires interdisciplinary methodologies that integrate historical, philosophical, and textual approaches. The specialized nature of this research demands familiarity with both historical medical concepts and theological frameworks.

Table: Essential Research Resources for Medieval Medical Ethics

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Manuscript Collections | National Library of Medicine MS E8; British Library medical manuscripts | Primary source analysis of medical and religious text integration |

| Historical Analyses | Monastic architectural plans (e.g., St. Gall); regulatory documents (e.g., Lateran Council decrees) | Contextual understanding of medical practice structures and limitations |

| Philosophical Texts | Aquinas's Summa Theologica; commentaries on natural law and conscience | Tracing development of ethical frameworks and their application to medicine |

| Specialized Scholarship | Studies on humoral theory transmission; monastic infirmary practices | Secondary literature providing interpretive frameworks and historical context |

The interpretive challenge for contemporary researchers lies in understanding these medieval developments within their proper historical context, avoiding both anachronistic judgments and uncritical acceptance of medieval perspectives. This requires careful attention to how medical practices were understood within their original frameworks and how ethical principles were applied in specific historical circumstances.

Contemporary Research Applications

For modern drug development professionals and researchers, understanding these historical foundations provides important context for contemporary bioethical discussions. The historical development of natural law theory continues to inform Catholic approaches to bioethical issues, while the monastic integration of spiritual and physical care offers precedents for holistic patient approaches.

The conceptual framework of medieval natural law theory, with its emphasis on fundamental human dignity and the moral accessibility of natural principles, provides an important historical foundation for understanding certain approaches to contemporary bioethical issues. Research into these historical developments can inform current debates by illuminating the philosophical and theological underpinnings of various positions on issues ranging from genetic technologies to end-of-life care.

The medieval synthesis of Galenic medicine, monastic care, and natural law theory created an enduring foundation for Western medical ethics that continues to influence contemporary bioethical discourse. The integration of these three elements provided a comprehensive framework for understanding health, disease, and moral responsibility that shaped medical practice and ethical reasoning for centuries. For modern researchers and healthcare professionals, understanding these historical developments provides crucial context for engaging with the philosophical and theological dimensions of current bioethical challenges. The medieval legacy demonstrates the enduring importance of integrating empirical knowledge, practical care, and ethical reflection in pursuing both health and healing.

The 1960s marked a definitive turning point in the history of bioethics, characterized by the emergence of a new, systematic field of inquiry that increasingly distanced itself from its theological foundations. This period witnessed a profound shift from ethics embedded within religious traditions to a secularized discipline oriented toward public policy and clinical application [17]. Prior to this transition, Christian theological perspectives had provided fundamental frameworks for understanding the relationship between medicine, morality, and the sacredness of life [18]. The contemporary bioethics that emerged, however, was largely structured around principlism and secular philosophical frameworks, effectively marginalizing theological voices that had historically shaped medicine's moral landscape [17] [19].

This paper examines the historical development of this shift, analyzing the forces that precipitated the marginalization of theological perspectives and tracing the consequent formation of a bioethics discipline where religious contributions were often relegated to the periphery. Understanding this transition is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who engage with bioethical frameworks, as it illuminates the historical context that shapes contemporary ethical discourse in clinical research and medical practice.

Historical Foundations: The Pre-1960s Landscape of Medical Ethics

Before the transformative period of the 1960s, medical ethics was predominantly shaped by religious traditions and professional guild standards. The Hippocratic tradition, originating in ancient Greece, established early practitioner ethics that emphasized healer virtuosity and duties to patients [4]. Within the Christian tradition, medical ethics was understood as an "expression of faithfulness," where life was viewed as a "precious gift from God" that physicians were called to serve rather than master [18] [4].

Key Features of Pre-Contemporary Medical Ethics

- Guild-Based Standards: Medical ethics primarily functioned as moral expectations for physicians, encompassing guild etiquette and vocational virtuosity [4].

- Theological Framework: Christian theological anthropology recognized humans as created in God's image (imago Dei), establishing a foundation for human dignity and the sanctity of life [18].

- Virtue-Based Approach: Emphasis was placed on the character of the medical practitioner rather than on abstract principles or decision-making procedures [4].

- Pastoral Focus: Early Christian writings on medical ethics often addressed issues related to sacraments, obedience to God's commandments, and the spiritual needs of patients rather than research ethics specifically [19].

This traditional approach began to fracture under the pressure of technological advancements and cultural shifts. Enormous advances in biology, particularly in genetics, raised new ethical questions that existing frameworks struggled to address [18]. Furthermore, a philosophical transition occurred from recognizing the "holiness of life" to talking about the "quality of living," representing a significant shift in how life's value was perceived [18].

The 1960s as Catalyst: Forces Driving a New Bioethics

The 1960s served as a catalytic decade during which multiple converging forces precipitated the emergence of contemporary bioethics as a distinct field. This period witnessed unprecedented technological and social changes that fundamentally challenged existing ethical paradigms.

Technological and Social Catalysts

Table 1: Primary Catalysts for the Emergence of Contemporary Bioethics in the 1960s

| Catalyst Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Bioethical Discourse |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Advances | Homologous and heterologous procreation in laboratory; human genome manipulation; genetic engineering [18] | Created novel ethical dilemmas beyond the scope of traditional medical ethics |

| Cultural Shifts | Transition from "holiness of life" to "quality of life" perspectives; growing emphasis on patient autonomy [18] | Challenged theological understandings of life's sacredness and purpose |

| Research Disclosures | Public revelation of abusive research practices (e.g., Nuremberg trials, Tuskegee study) [19] | Generated demand for formal ethical guidelines and oversight mechanisms |

| Religious Polarization | Controversy over contraceptive technology in the 1960s [17] | Accelerated the exodus of scholars from theological ethics to the burgeoning bioethics field |

The biotechnological revolution fundamentally altered medicine's capabilities, while simultaneously, a "point of transition from holiness of life to its quality had an impact on the quality of human relationships" [18]. This shift in perspective meant that "life is no longer perceived as being exclusively in God's hands, but in our hands as well," leading to a more subjective comprehension of life that diverged from traditional Christian views [18].

The Contraceptive Debate: A Critical Turning Point

The intense debate surrounding contraception in the 1960s served as a particularly significant test case that demonstrated the limitations of traditional theological ethics in addressing novel technological developments. This controversy caused "an exodus of scholars to join the burgeoning field of bioethics," as many found themselves in dissent against official church teaching [17]. This migration of intellectual capital from theological ethics to the emerging secular bioethics field substantially weakened the influence of theological voices while simultaneously strengthening the new discipline.

Mechanisms of Marginalization: How Theological Voices Were Sidelined

The marginalization of theological perspectives in bioethics occurred through several interconnected mechanisms that transformed bioethics from a discipline with significant religious participation to one dominated by secular frameworks.

The Ascendancy of Principlism

The development and adoption of principlism as the dominant framework for bioethical decision-making represented a crucial mechanism in the marginalization of theological voices. Principlism provided a "dominant philosophical model to be applied in policymaking and at the bedside" that appeared neutral and universally accessible [17]. This framework, most famously articulated in the Belmont Report's three principles (respect for persons, beneficence, and justice), was subsequently expanded into the "famous four principles of bioethics" that came to monopolize practical ethical deliberation [19].

The appeal of principism lay in its claim to secular universality – it offered a common language for ethical discussion that did not require adherence to any particular religious or philosophical tradition. However, this very feature meant that "the practical influence of Christian values in the ethics of biomedical research has been weakened and its historical meaning forgotten" [19]. The dominance of this approach in research ethics committees and institutional review boards created a structural barrier to theological contributions, as deliberations increasingly "turn[ed] around some fixed and recurrent topics" derived from principism rather than theological concepts [19].

Institutional and Structural Changes

Table 2: Institutional Mechanisms Marginalizing Theological Voices

| Mechanism | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Formalized Ethics Review | Establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and Research Ethics Committees (RECs) requiring application of standardized principles [19] | Created procedural barriers to theological ethical considerations |

| Regulatory Frameworks | Development of documents like the Belmont Report (1979) and revisions to the Declaration of Helsinki that codified secular principles [19] | Institutionalized secular frameworks in research regulation |

| Professionalization | Emergence of bioethics as a distinct professional field with its own training programs, journals, and career paths [17] | Marginalized theologian bioethicists in favor of secular professionals |

| Academic Secularization | Bioethics increasingly situated within secular philosophy departments rather than theological institutions [17] | Reduced influence of theological methodologies and assumptions |

The standardization of ethical review processes increasingly excluded theological considerations as irrelevant to public policy and regulatory decision-making. This institutionalization of secular bioethics created a self-reinforcing cycle: as theological voices were excluded from dominant discourse, their perspectives were perceived as less relevant, justifying further exclusion [19].

Consequences of Marginalization: The Contemporary Landscape

The marginalization of theological voices has produced a bioethics field with distinctive characteristics, limitations, and ongoing tensions.

Characteristics of Secularized Bioethics

Contemporary bioethics, shaped by the forces of secularization, displays several key features:

- Emphasis on Public Justification: Secular bioethics prioritizes arguments that can be justified through "public reason" rather than religious doctrines [20].

- Procedural Orientation: The focus has shifted toward processes (e.g., informed consent procedures) rather than substantive visions of the good life [19].

- Fragmentation of Ethical Frameworks: With the decline of principism's dominance, secular bioethics has witnessed a "plethora of competing models," many of which "seek to relocate ethics in the context of the situation or the character of the moral agent" [17].

- Path Toward Relativism: According to some critics, the secularization of bioethics has unwittingly put the field "on the path toward ethical relativism, liberalism and nihilism" [17].

Ongoing Tensions and Recent Developments

Despite the dominant secular paradigm, theological perspectives continue to contribute to bioethical discourse, particularly within specific religious traditions. Catholic bioethics has developed its approach with an "Agape structure of love" and emphasizes that "our biological nature must not be observed apart from the sense it has for us" [18]. Orthodox bioethics bases its ethical judgments on the "Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition" and emphasizes the concept of theosis (divinization) as the fulfillment of human potential [18].

Recent years have witnessed renewed debates about the proper role of religious perspectives in bioethics. The 2024 World Congress of Bioethics in Qatar, with its theme "Religion, Culture, and Global Bioethics," sparked controversy and highlighted the ongoing tension between secular and religious approaches [20]. Some scholars have argued for a pluriversal framework that would incorporate religious values more substantively, though this approach faces critiques regarding its consistency with human rights frameworks [20].

Analytical Framework: Visualizing the Historical Shift

The following diagram illustrates the key transitional period in the 1960s and the mechanisms through theological voices became marginalized in bioethics.

Research Toolkit: Analyzing the Bioethical Shift

For researchers investigating the historical development of bioethics and the marginalization of theological voices, the following conceptual toolkit provides essential frameworks and methodologies for rigorous analysis.

Table 3: Research Toolkit for Analyzing the Bioethics Historical Shift

| Research Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Historical Discourse Analysis | Examines how language and concepts change in bioethical literature over time | Tracking the declining frequency of theological terms in bioethics journals from 1960-1990 |

| Institutional History Mapping | Traces the development of ethics committees, regulations, and professional societies | Analyzing the founding principles of IRBs and their exclusion of theological members |

| Conceptual Framework Analysis | Identifies and compares underlying ethical frameworks and their assumptions | Contrasting the "sanctity of life" framework with "quality of life" approaches |

| Comparative Religious Ethics | Examines how different religious traditions approach bioethical questions | Analyzing differences in Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant responses to new technologies |

| Archival Research | Accesses primary historical documents from key figures and institutions | Studying personal papers of early bioethics pioneers to understand deliberate exclusion of theology |

The emergence of contemporary bioethics in the 1960s and the concomitant marginalization of theological voices represents a fundamental reorientation of how medicine and society approach ethical questions. This shift from theologically-grounded virtue ethics to secular principism has created a bioethics field that prioritizes procedural safeguards and public justification over substantive visions of human flourishing [17] [19].

For today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this history is crucial for several reasons. First, it illuminates the historical contingency of current ethical frameworks, revealing that they emerged from particular historical circumstances rather than representing inevitable or neutral approaches. Second, recognizing the limitations of secular bioethics – including its tendencies toward relativism and proceduralism – opens space for reconsidering what might be valuable in theological perspectives that were sidelined [17]. Finally, as contemporary bioethics grapples with unprecedented challenges posed by artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and global health inequities, there may be valuable resources in theological traditions that emphasize human dignity, the common good, and the proper limits of technological control over life [18] [21].

The ongoing tension between secular and religious approaches to bioethics, recently visible in forums like the 2024 World Congress of Bioethics, suggests that the question of theology's proper role in bioethics remains unresolved [20]. As the field continues to evolve, a more inclusive dialogue that engages both secular and theological perspectives may enrich bioethical discourse and provide more adequate resources for addressing the complex ethical challenges of contemporary biomedical research.

This whitepaper delineates the core theological principles that constitute the foundational bedrock for Christian bioethics, specifically contextualized within the historical development of this field. For researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development, understanding this framework is not merely an academic exercise but a critical lens through which the ethical dimensions of biomedical research and clinical application can be interpreted and navigated. The principles of Imago Dei (the image of God), the sanctity of life, stewardship, and agape love provide a coherent structure for evaluating emerging biotechnologies, from assisted reproductive technologies to end-of-life care. This document synthesizes these concepts into a structured format, complete with analytical tables and conceptual models, to serve as a technical reference for interdisciplinary engagement between theology, ethics, and the life sciences.

Foundational Principles: Conceptual Analysis and Definitions

The following table summarizes the core theological principles, their biblical foundations, and their primary bioethical implications.

Table 1: Core Theological Principles and Their Bioethical Correlates

| Theological Principle | Core Definition | Key Scriptural Foundations | Primary Bioethical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imago Dei (Image of God) | The unique designation of human beings as created to reflect and represent God, establishing inherent dignity, relational capacity, and God-given creativity [22] [23] [24]. | Genesis 1:26-27; Genesis 9:6; James 3:9 | Establishes inherent, non-contingent human dignity; grounds human rights; prohibits unjust killing; mandates respect for all persons regardless of capacity or function [25] [22] [24]. |

| Sanctity of Life | The belief that human life is sacred because it is created by and belongs to God, thus possessing intrinsic value that is not derived from human assessment or qualitative criteria [25] [26]. | Genesis 1:26-27; Job 33:4; Psalm 100:3; Matthew 5:21-22 | Opposes practices like abortion, euthanasia, and involuntary experimentation; demands positive duties to protect and preserve life, especially for the vulnerable [25] [27] [26]. |

| Stewardship | A limited, accountable dominion granted to humanity, characterized by service and responsible management of creation, health, and the physical body [23] [24]. | Genesis 1:28; Genesis 2:15; Psalm 8 | Frames human authority over nature (including biotechnology) as delegated and accountable; promotes sustainable practices and responsible innovation; opposes exploitation [23] [24]. |

| Agape Love | Self-sacrificial, unconditional love that seeks the genuine good of the other, modeled on God's love and the self-giving of Christ [23]. | Mark 12:30-31; John 13:34-35; 1 Corinthians 13 | Provides the ultimate motivational and normative framework for all bioethical principles; moves beyond mere rules to shape the character of care and the goals of medicine [23]. |

In-Depth Principle Exposition

1Imago Dei: The Ground of Human Dignity

The Imago Dei is the linchpin of a Christian anthropological framework. It is not located in a single human faculty (e.g., reason or will) but encompasses the whole person—intellect, emotion, volition, and body [23]. This "relational humanity" defines the human being in relation to God, meaning human identity and worth are derived from this divine reference point rather than from intrinsic properties alone [28]. The implications are profound: human dignity is universal and immutable, applying to all members of the human species regardless of age, cognitive capacity, physical ability, or social utility [22] [23]. This principle directly challenges bioethical frameworks that seek to ground personhood and moral status in variable criteria such as autonomy, rationality, or sentience. In laboratory and clinical settings, this translates to a mandatory ethical posture of respect for every human biological sample, embryo, fetus, patient, and research participant [22] [27].

Sanctity of Life: From Principle to Practice

The sanctity of life principle flows directly from the Imago Dei. Because human life is created by God and bears His image, its value is sacred [25] [26]. This principle was robustly affirmed by Jesus Christ, who expanded the prohibition against murder to include unjust anger and contempt, thereby addressing the heart attitudes that can lead to the devaluation of life (Matthew 5:21-22) [25] [26]. In bioethics, this principle imposes both negative and positive obligations. Negatively, it forbids the intentional taking of innocent human life. Positively, it commands the active protection and promotion of human flourishing [25]. This has clear relevance for debates concerning abortion, where the potentiality of the embryo argues strongly for its protection, and euthanasia, where the inherent value of life is separated from a subjective assessment of its quality [25] [27]. For the research scientist, this necessitates rigorous ethical review processes that vigilantly guard against the instrumentalization of human life at any stage.

Stewardship: The Framework for Technological Engagement

The creation mandate (Genesis 1:28) grants humanity a form of dominion over the natural world. However, this is correctly understood as "accountable dominion" or stewardship, modeled after God's own caring and creative governance [23] [24]. This dominion is not a license for exploitation but a call to loving service and cultivation, as illustrated by God placing Adam in the garden "to work it and keep it" (Genesis 2:15) [24]. In the context of modern biotechnology, stewardship provides a critical framework for engaging with powerful new technologies. It affirms the goodness of scientific inquiry and technological innovation as means to alleviate suffering and improve human health—a manifestation of agape love. Simultaneously, it sets boundaries, demanding that such power be exercised with humility, wisdom, and a profound sense of accountability to the Creator for its consequences on human life and the wider creation [29].

4AgapeLove: The Unifying Norm

While the previous principles provide specific ethical directives, agape love serves as the unifying and supreme norm that animates and integrates them all [23]. This love, defined by self-giving and commitment to the good of the neighbor, is the ultimate fulfillment of the moral law (Matthew 22:37-40). In bioethics, it moves the discussion beyond compliance with rules toward the formation of moral character and the motivation for compassionate action. It calls the researcher and clinician not merely to avoid harm, but to actively seek the well-being of the patient and participant, prioritizing the vulnerable and modeling the love of Christ. This principle ensures that Christian bioethics remains fundamentally personal and relational, rather than descending into a cold, impersonal application of rules.

Conceptual and Historical Development Model

The following diagram maps the logical and historical relationships between the core theological principles and their impact on the development of Christian bioethics.

Diagram 1: Theological Foundations of Bioethics

Analytical Framework for Research Methodology

The application of these theological principles to concrete bioethical issues requires a structured methodology. The following table outlines a potential analytical framework for evaluating bioethical questions, translating theological concepts into research parameters.

Table 2: Analytical Framework for Theological Bioethics Research

| Research Phase | Methodological Action | Theological Input | Output/Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem Definition | Identify the specific bioethical issue or technology (e.g., germline editing, AI in diagnostics). | N/A | A clearly defined research problem statement. |

| 2. Anthropological Analysis | Analyze the issue through the lens of the Imago Dei. | Doctrine of humanity as relational, embodied, and possessing inherent dignity [28] [23]. | How does the technology impact the understanding of human identity, dignity, and relationality? |

| 3. Sanctity Evaluation | Assess the technology's impact on human life. | The sanctity of life principle, including its positive (protect) and negative (do not kill) demands [25] [26]. | Does the technology preserve, threaten, or destroy human life? Does it promote human flourishing? |

| 4. Stewardship Assessment | Evaluate the scope and exercise of human authority. | Stewardship as accountable dominion, oriented toward service and the common good [23] [24]. | Is this technology a responsible exercise of our creative power? To whom are we accountable for its use and consequences? |

| 5. Normative Integration | Apply the principle of agape love as the final norm. | Agape as self-sacrificial, neighbor-loving action [23]. | Does the application of this technology reflect Christ-like love? Does it prioritize the vulnerable? |

| 6. Ethical Conclusion | Synthesize findings into a normative position. | The coherent integration of all principles. | A theologically grounded ethical stance on the technology or issue. |

Essential Research Reagents for Theological Bioethics

Engaging in rigorous bioethical research from a Christian perspective requires a "toolkit" of core resources. The following table details these essential conceptual reagents.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Christian Bioethics

| Research Reagent | Function | Key Compositions / Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Scriptural Foundation | Provides the primary source material and ultimate authority for normative claims. | Genesis 1-3; Psalm 8; Matthew 5-7; Pauline epistles (e.g., Romans, Ephesians) [25] [23] [24]. |

| Historical Theology | Offers the developed understanding of key doctrines across church history. | Augustinian relational anthropology [28]; Reformation covenant theology [30]; modern theological anthropology [22]. |

| Philosophical Frameworks | Provides logical structure and analytical tools for argumentation. | Natural law theory (when properly grounded in divine law) [27]; virtue ethics; phenomenology. |

| Scientific Literature | Supplies empirical data on the technical aspects, capabilities, and consequences of biotechnologies. | Peer-reviewed journals in genetics, neuroscience, artificial intelligence, and clinical medicine. |

| Existing Bioethical Analysis | Serves as a point of engagement, critique, and dialogue. | Works by thinkers addressing the intersection of theology, philosophy, and medicine [27] [29]. |

The core theological principles of Imago Dei, the sanctity of life, stewardship, and agape love form a robust and non-arbitrary foundation for Christian bioethics. This framework provides a comprehensive account of human dignity, moral obligations, and the proper scope of human technological activity. For the scientific and research community, engagement with this framework is not a call to abandon reason but to situate technical reason within a broader context of wisdom, purpose, and moral commitment. As biotechnology continues to advance at a rapid pace, this theological bedrock offers a stable point of reference for ensuring that scientific progress remains aligned with a authentic and truly human—flourishing.

A Framework for Ethical Decision-Making: Applying Christian Principles to Modern Biomedical Challenges

The Christian engagement with bioethical issues concerning the taking of human life represents a complex tradition spanning two millennia. Rooted in both divine revelation and natural law reasoning, Christian perspectives on abortion, physician-assisted suicide (PAS), and euthanasia have evolved within specific historical and theological contexts while maintaining certain foundational commitments. This paper examines the historical development of these perspectives, analyzing how Christian thought has consistently emphasized the sanctity of human life while navigating changing medical technologies and social circumstances. From the early Church's stand against prevailing Greco-Roman practices to contemporary debates about medical assistance in dying (MAiD), Christian bioethics has served as a counter-cultural force in discussions about life's value and limits [31] [32].

Framed within a broader thesis on the historical development of Christian bioethics research, this analysis demonstrates how Christian approaches to these "taking life" dilemmas integrate theological commitments with philosophical reasoning. The historical review of euthanasia reveals a pivotal transition from ancient Greek and Roman acceptance to Christian prohibition, followed by contemporary re-evaluation [31]. Similarly, Christian opposition to abortion represents what historian W.E.H. Lecky acknowledged as "one of the most important services of Christianity" in elevating protection for nascent life [33]. This paper traces these developmental trajectories while providing researchers with analytical frameworks for understanding current debates.

Historical Development of Christian Perspectives

Foundations in Early Christian Thought

Early Christian writings universally condemned abortion and the intentional taking of innocent life, distinguishing Christian communities from their surrounding cultures. The Didache (c. 1st-2nd century AD) explicitly prohibited abortion: "You shall not murder a child by abortion nor kill that which is born" [33] [32]. This stance contrasted sharply with Greco-Roman society, where, as Lecky notes, "The practice of abortion was one to which few persons in antiquity attached any deep feeling of condemnation" [33]. Similarly, euthanasia, which had been accepted in ancient Greece and Rome as a means to avoid suffering or maintain honor, was re-evaluated through a Christian worldview [31].

Early Christians grounded their opposition to these practices in several key theological premises: the Imago Dei (humanity created in God's image), the sanctity of life as a divine gift, and the prohibition against killing the innocent [34] [32]. As David Braine's study concludes: "For the whole of Christian history until appreciably after 1900… there was virtually complete unanimity amongst Christians, evangelical, catholic, orthodox, that, unless at the direct command of God, it was in all cases wrong directly to take innocent human life" [33]. This consensus formed the foundation for Christian bioethics throughout most of Church history.

Key Historical Transitions and Developments

Table 1: Historical Transitions in Christian Bioethical Perspectives

| Historical Period | Cultural Context | Christian Stance | Key Developments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greece & Rome | Abortion common; Euthanasia accepted for honor/suffering | Emerging opposition based on sanctity of life | Contrast with pagan practices; Development of moral theology |

| Early Church (1st-4th C.) | Persecution; Infant exposure common | Universal condemnation in Christian writings | Didache; Church fathers consistently oppose abortion & euthanasia |

| Middle Ages | Catholic dominance in Europe | Formal theological development | Thomas Aquinas condemns suicide; Double Effect principle formulated |

| Reformation Era | Religious fragmentation | Doctrinal continuity on life issues | Calvin describes fetus as "already a human being" |

| 19th-early 20th C. | Medicalization; Eugenics movement | Opposition to non-therapeutic killing | Response to eugenics; AMA early abortion restrictions |

| Post-WWII | Nazi euthanasia programs revealed | Strengthened protection of vulnerable | Connection between euthanasia and eugenics recognized |

| Late 20th C. | Legalization of abortion & PAS | Denominational statements; Political engagement | Roe v. Wade (1973); First PAS laws (1990s); Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (1973) |

| 21st Century | Expanding MAiD laws | Continued opposition with palliative care emphasis | Canada's MAiD (2016); Mental illness as sole indication (2027) |

The Middle Ages witnessed significant theological development regarding these issues. Thomas Aquinas condemned suicide in the 13th century, arguing that it "interferes with the natural inclination of self-perpetuation, injures communities, and violates God's authority" [35]. Ironically, Aquinas also formulated the Rule of Double Effect in his Summa Theologica, which would later become important in end-of-life ethical decisions [35]. This principle acknowledges that sometimes morally permissible actions (like relieving pain) may have foreseen but unintended negative consequences (like potentially hastening death).

The modern era brought significant challenges to traditional Christian perspectives. The 20th century witnessed the legalization of abortion in many jurisdictions, beginning with the 1967 Abortion Act in England and Wales [33]. Similarly, PAS and euthanasia gained traction, with Jack Kevorkian's activities in the 1990s drawing significant attention to assisted suicide [35] [36]. Christian responses varied, with some denominations maintaining absolute opposition while others developed more nuanced positions that considered maternal health or extreme circumstances [37].

Conceptual Frameworks and Ethical Foundations

Theological and Philosophical Foundations

Christian approaches to "taking life" dilemmas rest on several foundational principles. The sanctity of life doctrine serves as the cornerstone, asserting that human life possesses intrinsic value because humans are created in God's image (Imago Dei) [34]. This perspective contrasts with utilitarian approaches that assess life's value based on quality-of-life metrics or capacity for meaningful experiences [36]. As the Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity notes, dignity is "rooted in being created in the image and likeness of God," meaning it cannot be lost regardless of one's physical or mental state [38].

Christian bioethics typically employs a deontological ethical framework that recognizes certain duties and moral absolutes, rather than the consequentialist approach of utilitarianism [36]. This aligns with natural moral law theory, which posits that fundamental moral principles are accessible through reason and grounded in human nature [36]. From this perspective, acts like intentionally killing innocent human beings are intrinsically wrong, regardless of consequences [36].

Key Ethical Distinctions and Principles

Several key distinctions shape Christian ethical analysis of these issues:

- Killing vs. Allowing to Die: Traditional Christian ethics distinguishes between intentionally causing death (prohibited) and withholding or withdrawing burdensome treatments when death is imminent (permissible) [36].

- Ordinary vs. Extraordinary Treatments: Christians have generally held that patients are not obligated to pursue medically futile or disproportionately burdensome interventions [36].

- Principle of Double Effect: An action with both good and bad effects may be permissible if the bad effect is not intended and is proportionate to the good effect [35].

These distinctions allow for nuanced approaches to end-of-life care while maintaining a commitment to the sanctity of life.

Abortion: Christian Perspectives and Historical Development

Historical Christian Position on Abortion