Developing an Effective Bioethics Curriculum for Medical Schools: Evidence-Based Strategies for Integrating Ethics into Medical Education

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing, implementing, and evaluating bioethics curricula in medical education.

Developing an Effective Bioethics Curriculum for Medical Schools: Evidence-Based Strategies for Integrating Ethics into Medical Education

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing, implementing, and evaluating bioethics curricula in medical education. Drawing on recent global research and evaluation studies, it addresses foundational principles, innovative teaching methodologies, solutions for common implementation challenges, and robust validation techniques. Designed for medical educators, curriculum developers, and institutional leaders, the content synthesizes evidence from successful long-term programs, including integrated spiral curricula, Team-Based Learning (TBL), and performable case studies, offering practical strategies for creating ethically competent physicians prepared for modern biomedical challenges.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and the Evolving Scope of Bioethics Education

Bioethics, broadly defined as the interdisciplinary study of ethical, legal, and social issues arising in the life sciences and health care, emerged as a formal discipline in the late 1960s against a backdrop of profound medical tragedies and societal transformations [1]. This field has since transformed medical practice and policy-making concerning issues ranging from public health and medical care delivery to agricultural biotechnology. The development of structured bioethics curricula represents a direct response to historical events where medical professionalism and research ethics dramatically failed, creating an imperative to equip healthcare professionals with the ethical reasoning necessary to navigate complex moral dilemmas. This whitepaper traces the journey from these tragic origins to the formalized educational frameworks implemented in modern medical education, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of evidence-based approaches to bioethics curriculum development.

The historical arc of bioethics education reveals a field continually evolving to address emerging challenges—from initial concerns about human subjects research to contemporary issues involving artificial intelligence, genomics, and global health equity. Modern bioethics curricula now represent essential components of medical education, mandated by accrediting bodies like the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and integrated throughout undergraduate and graduate medical training [2] [3]. This paper examines the historical imperative driving this educational evolution, assesses current evidence-based curricular models, and provides methodological frameworks for developing effective bioethics education tailored to contemporary medical and research environments.

Historical Foundations: From Tragedy to Formalized Ethics

The formalization of bioethics as a discipline directly reflects medicine's ethical reckoning with twentieth-century tragedies, particularly those involving abuse of human subjects in research. The Nuremberg Doctors' Trial of 1946-1947, where 23 high-ranking Nazi doctors and administrators were tried for war crimes and crimes against humanity including non-consensual medical experiments, established a pivotal historical foundation for modern bioethics [1]. The trial exposed horrific medical abuses and produced the Nuremberg Code (1947), whose first principle established that "the voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential" [1]. This document, while initially having limited immediate impact on research practices, eventually became the cornerstone for all subsequent research ethics frameworks.

Other historical cases further cemented the need for formal ethics oversight and education. The Guatemala Syphilis Studies (1946-1948), where U.S. researchers intentionally infected more than 1,300 Guatemalan soldiers, prisoners, and mental patients with sexually transmitted diseases without consent, remained buried in archives until 2010 but exemplify the ethical breaches that bioethics education seeks to prevent [1]. In response to these and other ethical failures, various codes and declarations emerged throughout the mid-twentieth century, including the Declaration of Geneva (1948) as a new secular physician's oath, the World Medical Association's International Code of Medical Ethics (1949), and principles adopted by the American Medical Association for permissible human experimentation [1].

Table 1: Historical Foundations of Modern Bioethics

| Year | Event | Significance | Impact on Bioethics Education |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1946-1947 | Nuremberg Doctors' Trial | Exposed horrific medical experiments on prisoners without consent | Established necessity of voluntary consent as foundational principle |

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code | First international document specifying principles for human subjects research | Provided core content for research ethics education |

| 1948 | Declaration of Geneva | Established secular physician's oath in aftermath of WWII | Became model for professional ethics training |

| 1960s-1970s | Bioethics as Formal Discipline | Field emerged addressing ethics of new medical technologies | Created need for structured curricula in medical education |

| 1979 | Belmont Report | Established ethical principles for research in United States | Standardized research ethics education requirements |

The evolution of these historical responses demonstrates a pattern: ethical breach, investigation, policy response, and eventual educational integration. This pattern underscores the preventive function of bioethics education—equipping professionals with ethical frameworks before rather than after crises occur. The formalization of bioethics curricula throughout the 1970s and 1980s represented the institutionalization of this hard-won historical knowledge, transforming tragic lessons into proactive educational frameworks [1].

Current Bioethics Curriculum Frameworks and Evidence

Contemporary bioethics education has evolved from historical foundations to become formally integrated throughout medical education, with evidence supporting specific curricular approaches and methodologies. Current frameworks span undergraduate medical education, graduate medical training, and dual-degree programs, incorporating varied pedagogical methods to address increasingly complex ethical challenges in healthcare and research.

Curriculum Integration Models and Effectiveness

Research demonstrates that effective bioethics curricula share several key characteristics: longitudinal integration throughout training, use of interactive pedagogical methods, and application of ethical principles to real-world clinical scenarios. A comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation of a bioethics curriculum implemented for over a decade in a five-year undergraduate medical program demonstrated significant effectiveness in student development [3] [4]. The quantitative results from this study revealed that the majority of students agreed the curriculum contributed to their knowledge acquisition (60.3-71.2%), skill development (59.41-60.30%), and demonstration of ethical/professional behavior (62.54-67.65%) [3] [4].

Table 2: Bioethics Curriculum Effectiveness in Undergraduate Medical Education

| Learning Domain | Student Agreement (%) | Key Contributing Factors | Implementation Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Acquisition | 60.3-71.2% | Spiral integration across curriculum; relevant content | Basic knowledge acquisition in Years 1-2 with reinforcement in clinical years |

| Skill Development | 59.41-60.30% | Case-based learning; small group discussions | Opportunities for application in clinical settings; ethics consultation simulation |

| Ethical/Professional Behavior | 62.54-67.65% | Role modeling; clinical integration | Involvement of clinical faculty; explicit linking of principles to practice |

The study employed a sequential explanatory mixed methods design, beginning with a structured online questionnaire completed by 500 students across all five years of the medical program, followed by focus group discussions and document review to explain and enrich the quantitative findings [3] [4]. This methodology provided both breadth and depth of understanding regarding curriculum effectiveness. Importantly, the research identified that multi-modal instructional methods were particularly effective, with students and faculty emphasizing the value of small group teaching and shorter sessions for fostering discussion and maintaining engagement, while large class formats were significantly less effective [3].

Graduate Medical Education and Team-Based Learning

At the graduate medical education level, Team-Based Learning (TBL) has emerged as an evidence-based approach to bioethics instruction. A comprehensive TBL curriculum implemented with pediatric residents demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge and ethical analysis capabilities [2]. The curriculum, developed around L. Dee Fink's principles of "Significant Learning" and Jonsen et al.'s "Four-Box Method" of ethical analysis, included 10 adaptable modules covering essential bioethics topics including introduction to medical ethics, assent and consent, professionalism and social media, neonatal and perinatal ethics, and pediatric palliative care [2].

The study methodology employed a three-year longitudinal, integrated approach with 348 total resident encounters. Assessment included Individual and Group Readiness Assessment Tests (iRAT/gRAT), pre-work completion measurement, and satisfaction surveys [2]. Results demonstrated that gRAT scores (mean 89%) showed significant improvement compared to iRAT scores (72%) across all TBL sessions and all post-graduate years (p < .001), indicating that collaborative learning enhanced ethical reasoning capabilities [2]. Higher gRAT scores correlated with more advanced training levels, suggesting developing clinical experience enhances ethical analysis skills. Despite low pre-work completion (28%), satisfaction was high (4.42/5 on Likert scale), indicating strong engagement with the TBL methodology [2].

Core Content Areas and Emerging Topics

Modern bioethics curricula have expanded beyond traditional topics to address emerging ethical challenges at the frontiers of medicine and technology. Core graduate-level courses now include:

- Philosophical Bioethics: Examining fundamental questions about life, death, and the provider-patient relationship through ethical frameworks [5]

- Law and Bioethics: Contrasting legal reasoning and ethical analysis of the same issues [5]

- Clinical Ethics: Developing consultation skills for clinical ethical dilemmas [5]

- Global Bioethics: Examining how varying economic, political, social, and cultural contexts shape ethical issues [5]

- Research Ethics: Addressing challenges in human subjects research and professional scientific conduct [5]

Emerging elective courses reflect evolving ethical frontiers, including:

- AI and Bioethics: Addressing the ethical implications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in healthcare, training ethicists to "help steer AI use in safe and productive ways" [5]

- Animals and Bioethics: Examining ethical issues in the use of non-human animals in biomedical research and emerging technologies [5]

- Pandemic Ethics: Exploring ethical decision-making in infectious disease outbreaks, drawing lessons from COVID-19 and historical pandemics [5]

These content areas reflect the expanding scope of bioethics education as it addresses both perennial ethical questions and emerging challenges created by technological and social changes.

Implementation Methodologies and Curricular Design

Effective bioethics education requires deliberate pedagogical strategies and implementation methodologies. Evidence supports specific approaches to curricular design, teaching methods, and integration frameworks that maximize educational effectiveness across different learner levels and institutional contexts.

Pedagogical Frameworks and Instructional Methods

The Team-Based Learning methodology implemented in graduate medical education provides a robust framework for bioethics instruction [2]. The TBL process comprises five essential components: (1) establishing clear learning outcomes; (2) pre-session preparation; (3) Individual Readiness Assurance Test (iRAT); (4) Group Readiness Assurance Test (gRAT); and (5) Team Application Exercise (TApp) where learners apply knowledge to complex ethical scenarios [2]. This methodology promotes significant learning through active discussion and immediate application of ethical concepts to clinically relevant situations.

The "Four-Box Method" of ethical analysis provides a structured approach for evaluating clinical ethical cases [2]. This method, integrated into TBL application exercises, guides learners to analyze cases through four essential dimensions: medical indications, patient preferences, quality of life, and contextual features. This structured approach provides residents with a consistent method of ethical analysis that can be applied across diverse clinical scenarios, becoming a "deliverable skill" similar to other clinical reasoning algorithms [2].

For undergraduate medical education, research supports multi-modal instructional approaches including lectures, discussions, brainstorming, problem-solving exercises, videos/movies, and case studies [3]. The integration of bioethics within existing problem-based learning (PBL) curricular frameworks facilitates contextual understanding and application of knowledge [3]. Studies indicate that learning embedded in an integrated curriculum helps students recognize, critically analyze, and address ethical dilemmas they will encounter in clinical practice [3].

Integration Strategies and Longitudinal Implementation

Research supports longitudinal integration of bioethics throughout the entire medical education continuum rather than as isolated courses or lectures. An effective bioethics curriculum for undergraduate medical education should run across the five-year curriculum, integrated within modules and clerkships [3]. Basic knowledge and skill acquisition occurs in the first two years, with reinforcement and application in clinical years [3]. This spiral approach allows for repeated exposure to ethical concepts at increasing levels of complexity and clinical relevance.

Critical to successful implementation is the involvement and commitment of clinical faculty in reinforcing ethical principles and concepts learned in earlier years [3]. Studies indicate that better integration in clinical years, role modeling, and providing opportunities for application in clinical healthcare settings significantly strengthen bioethics curricula [3]. Participants in evaluation studies have suggested additional topics for modern curricula, including ethical issues related to social media, public health ethics, and the intersection of ethics and law [3].

For graduate medical education, bioethics curricula must be both practical and flexible in implementation, adaptable to different specialties, virtual formats, and specific institutional needs [2]. The TBL approach has demonstrated effectiveness across different situational factors, disciplines, and levels of clinical experience [2]. This flexibility is particularly important given the "crowding in the curriculum" that represents a significant barrier to graduate medical education innovations [2].

Implementing effective bioethics education requires specific resources, tools, and methodological approaches. The following research reagents and solutions represent essential components for developing, implementing, and evaluating bioethics curricula across educational contexts.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bioethics Curriculum Development

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBL Framework | Structured pedagogical approach for ethics education | Graduate medical education; small group learning | Requires facilitator training; adaptable modules |

| Four-Box Method | Ethical analysis framework for clinical cases | Clinical ethics education; case analysis | Provides consistent approach across cases |

| Mixed Methods Evaluation | Comprehensive curriculum assessment | Program evaluation; quality improvement | Sequential explanatory design: quantitative then qualitative |

| Integrated Spiral Curriculum | Longitudinal educational approach | Undergraduate medical education | Basic concepts in pre-clinical years with clinical application |

| Digital Accessibility Tools | Ensure inclusive educational materials | Online and hybrid education | Color contrast checkers; multiple content modalities |

The TBL framework serves as a primary "research reagent" for effective bioethics education, providing a structured methodology that promotes engagement and application of ethical principles [2]. Essential to this approach are the specific components of iRAT, gRAT, and TApp exercises that create a progressive learning experience from individual knowledge assessment to collaborative application.

The Four-Box Method represents another critical "reagent" for ethical analysis, offering a consistent framework that learners can apply across diverse clinical scenarios [2]. This methodological tool helps structure ethical reasoning while acknowledging the complexity of clinical realities.

Evaluation methodologies, particularly mixed methods approaches combining quantitative surveys with qualitative focus groups and document analysis, serve as essential "reagents" for curriculum assessment and refinement [3] [4]. These methodological tools provide both breadth and depth of understanding regarding curriculum effectiveness, enabling evidence-based improvements.

Future Directions and Emerging Challenges

Bioethics education continues to evolve in response to emerging technologies, changing healthcare systems, and global health challenges. Future curriculum development must address several critical areas to maintain relevance and effectiveness in preparing healthcare professionals for ethical challenges at the frontiers of medicine.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning represent one of the most significant emerging domains requiring ethical analysis. As noted in contemporary curricula, "Computer scientists, coders, and engineers best understand the development and use of Machine Learning, but often lack training in ethics, law, and public policy" [5]. This creates an urgent need for ethicists with understanding of AI to "help steer AI use in safe and productive ways" [5]. Future bioethics curricula must bridge this technical-ethical divide, equipping professionals with the analytical frameworks necessary to address ethical implications of AI in healthcare and research.

Global bioethics represents another expanding frontier, requiring attention to how "varying economic, political, social, cultural, and historical contexts shape these issues" across different regions and resource settings [5]. Multinational research, "reproductive tourism," and differing approaches to end-of-life care across national borders all highlight the need for globally informed ethical frameworks [5]. Bioethics education must prepare professionals for these transnational ethical challenges while respecting cultural diversity and contextual differences.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted persistent challenges in public health ethics, including issues of government preparedness, resource allocation, vaccine development, and public communication [5]. Future curricula must incorporate these lessons, exploring "how bioethical and policy decision-making can have different effectiveness in the context of modern pandemics" [5]. These contemporary challenges underscore the continuing relevance of the historical imperative in bioethics education—applying lessons from past ethical successes and failures to emerging challenges in healthcare and research.

The development of formal bioethics curricula represents a direct response to medicine's ethical failures and a commitment to preventing their recurrence through education. From the tragic origins exemplified by the Nuremberg Trials to contemporary ethical challenges posed by emerging technologies, bioethics education has evolved from historical imperative to educational necessity. Evidence-based approaches including longitudinal integration, Team-Based Learning methodologies, mixed methods evaluation, and structured ethical analysis frameworks provide effective strategies for developing healthcare professionals equipped to navigate complex ethical dilemmas.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this historical imperative and its translation into formal educational frameworks is essential both for their own ethical development and for contributing to the evolution of bioethics education. As medical science continues to advance, bringing new ethical challenges, the lessons of history remain relevant: that ethical education is not peripheral but central to medical professionalism, and that preventing ethical breaches requires proactive education rather than retrospective response. The continued refinement of bioethics curricula represents an ongoing commitment to this principle, ensuring that healthcare professionals at all levels possess the ethical reasoning capabilities necessary to navigate the complex moral landscape of modern medicine.

The evolution of medical education highlights a critical shift from a process-time-based model to a competencies-driven framework, focusing on the definitive outcomes graduates must demonstrate. This transition is underscored by global research revealing significant gaps in essential competencies among medical graduates. A seminal European cross-sectional study evaluating 895 final-year students from 26 medical schools found an overall lack of essential prescribing competencies, including poor knowledge of drug interactions and contraindications, and the selection of inappropriate therapies for common diseases [6]. These deficiencies directly impact patient safety and quality of care, signaling an urgent need for standardized competency frameworks. Within this educational landscape, bioethics education serves as a fundamental pillar, not merely as a discrete subject but as an integrative thread that enables the embodiment of humanistic, professional, and ethical principles across all medical practice. The development of a core competencies framework, therefore, provides the necessary structure to ensure medical schools cultivate professionals who are not only technically proficient but also ethically grounded and socially responsible [7] [8].

Global Landscape of Medical Competencies: Current Status and Identified Gaps

Quantitative Deficits in Core Competencies

Table 1: Documented Deficiencies in Medical Graduate Competencies

| Competency Area | Deficiency Documented | Study Population | Impact on Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics | Poor knowledge of drug interactions/contraindications; inappropriate therapy selection [6] | 895 final-year students across 26 European schools | Leads to prescribing errors and potentially unsafe patient care [6] |

| Bioethics Knowledge & Application | Lack of formal, integrated bioethics curriculum in many regions [8] | Medical schools in Africa, Asia, and Portuguese-speaking countries | Inability to critically process ethical dilemmas in clinical settings [7] [8] |

| Mental, Neurological, Substance Use (MNS) Care | Lack of thorough training for general health-care providers [9] | Medical and nursing students globally | Failure to provide care for one in eight people living with MNS conditions [9] |

Bioethics Curriculum Implementation: A Variable Global Picture

The integration of bioethics into medical curricula remains inconsistent worldwide. Studies from Portuguese-speaking countries reveal that while 65.5% of medical schools met the minimum 30-hour workload recommended by UNESCO, the curricular structure, content, and integration point varied significantly, with most offering ethics sporadically at the program's end [8]. This lack of formalization and standardization is a recurring challenge. In contrast, evaluation studies of longitudinal, spiral bioethics curricula, such as one implemented for over a decade in a Pakistani medical college, show more promising results. In such models, a majority of students agreed the curriculum contributed to their knowledge acquisition (60.3–71.2%), skill development (59.41–60.30%), and demonstration of ethical behavior (62.54–67.65%) [7]. These findings highlight that the structure, duration, and integration of ethics education are as critical as its mere presence.

Defining the Core Competency Domains for Medical Graduates

A comprehensive synthesis of global frameworks and research findings reveals three interdependent competency domains essential for every medical graduate.

Professional Competencies and Bioethical Integration

This domain encompasses the attributes, behaviors, and moral reasoning necessary for trustworthy medical practice. The AAMC categorizes these as "Professional Competencies," which include resilience, interpersonal skills, and a service orientation [10]. The University of Saskatchewan's MD program further elaborates these as "Behavioral and Social Attributes," requiring good judgement, self-awareness, ethical responsibility, and cultural humility [11]. Bioethics education is the scaffold upon which these competencies are built, moving beyond theoretical knowledge to foster the demonstration of ethical and professional behavior in patient care [7]. This involves a commitment to lifelong learning, personal integrity, and the ability to navigate complex interpersonal dynamics with empathy and compassion [10] [11].

Thinking, Reasoning, and Scientific Competencies

This domain involves the analytical and knowledge-based skills required for clinical reasoning and scientific inquiry.

- Critical Thinking & Scientific Inquiry: The ability to analyze complex problems, integrate information from histories, physical exams, and lab data to formulate a differential diagnosis and management plan is a core intellectual-conceptual skill [11]. This aligns with the AAMC's "Thinking and Reasoning" competencies, which include critical thinking and quantitative reasoning to evaluate evidence and solve clinical problems [10].

- Living Systems & Human Behavior: A robust understanding of human biology—from molecular to systemic levels—and the psychological, social, and biological factors that influence health is foundational [10]. These "Science Competencies" underpin the ability to understand disease processes and treatment mechanisms.

Functional and Technical Competencies

These are the observable, practical skills required to perform the duties of a physician.

- Communication Skills: The ability to communicate effectively and sensitively with patients, families, and colleagues across cultural, age, and social boundaries is paramount. This includes verbal, non-verbal, and written communication, and the capacity to recognize and respond to emotional cues [11].

- Observational and Procedural Skills: Graduates must possess the sensory and motor functions to perform physical examinations and procedural skills competently and safely. This requires accurate observation of signs of illness and competent use of medical equipment [11].

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: A modern and essential competency is the ability to contribute to inclusive learning and work environments, address personal biases, and ensure equitable care for all patients [11].

Experimental and Methodological Approaches to Curriculum Development

Research Protocols for Competency Framework Development

Establishing a valid and relevant competency framework requires rigorous, multi-method research approaches.

Protocol 1: Mixed-Methods Curriculum Evaluation

- Objective: To assess the effectiveness of an integrated bioethics curriculum in terms of student achievement, content appropriateness, and instructional method efficiency [7].

- Quantitative Phase: Administer a structured online questionnaire to a large sample of students (e.g., N=500) across all years of the program. Utilize a model like Context, Input, Process, Product (CIPP) to develop questions rated on a Likert scale [7].

- Qualitative Phase: Conduct Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with students and faculty to explain and enrich quantitative findings. Perform document reviews of curriculum materials to check alignment with objectives [7].

- Data Synthesis: Integrate datasets to identify convergent and divergent themes. For example, quantitative data may show high satisfaction with small-group teaching, which qualitative data can then explain by highlighting its interactive nature [7].

Protocol 2: Cross-Sectional Competency Gap Analysis

- Objective: To evaluate the essential competencies of final-year medical students across multiple regions [6].

- Design: International, multicenter, cross-sectional study.

- Sampling: Administer a standardized assessment (e.g., knowledge tests, scenario-based assessments) and questionnaire to a defined number of final-year students (e.g., 50) from each participating medical school [6].

- Analysis: Perform quantitative analysis of assessment scores to identify specific competency gaps at both an aggregate level and per institution.

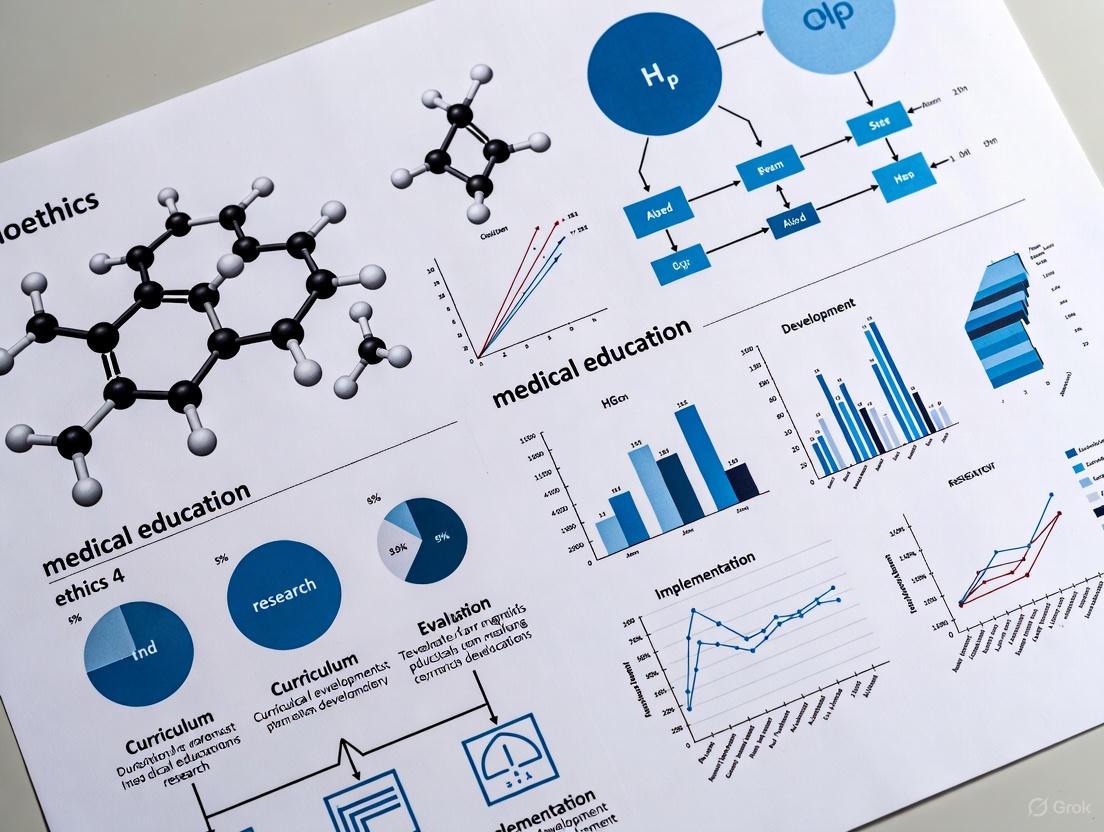

Visualization of Integrated Curriculum Development

The following diagram illustrates the systematic, multi-stakeholder process for developing and evaluating a competencies-based medical curriculum, particularly for bioethics.

Research Reagent Solutions for Educational Research

Table 2: Essential Methodological Tools for Competency Research

| Research 'Reagent' | Function in Curriculum Development | Exemplar Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Questionnaire | Quantitatively measures perceptions of competency achievement, curriculum relevance, and teaching effectiveness. | Used with Likert scales to gauge student agreement on knowledge acquisition (60.3-71.2%) and skill development (59.41-60.30%) [7]. |

| Focus Group Discussion (FGD) Guide | Elicits rich, qualitative data on lived experiences, unexplored challenges, and nuanced suggestions for improvement. | Explains why large class formats are less effective and gathers suggestions for topics like social media ethics [7]. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Guide | Gathers in-depth perspectives from key stakeholders (e.g., faculty, clinical preceptors) on implementation barriers and enablers. | Used with faculty to understand challenges in reinforcing ethics in clinical years and the role of hidden curriculum [7] [12]. |

| Standardized Competency Assessment | Objectively measures specific competency levels across different institutions using a validated instrument. | Employed in a European cross-sectional study to identify prescribing deficits among final-year students [6]. |

| Document Analysis Protocol | Systematically reviews official curriculum documents, syllabi, and learning objectives for alignment with competency goals. | Used to analyze 58 medical school curricula in Brazil and Portugal against the UNESCO Core Curriculum benchmark [8]. |

Discussion and Future Directions: Implementing and Sustaining Competency Frameworks

The path to implementing a successful competencies-based curriculum, particularly in bioethics, is fraught with challenges but rich with opportunity. A primary obstacle is the "hidden curriculum" – the unspoken values and behaviors modeled by clinical faculty that can undermine formal ethics teaching if not aligned [8] [12]. Overcoming this requires more than student assessment; it demands faculty development and the explicit involvement and commitment of clinical faculty to model and reinforce ethical principles [7]. Furthermore, as a study of a diverse student elective highlighted, interactive teaching formats are the most preferred for ethics education, and topics must be contextually relevant, with truth-telling emerging as a critical subject [13]. Future efforts must focus on creating longitudinal and spirally integrated curricula that begin in pre-clinical years and are reinforced and applied throughout clinical training [7] [8]. This ensures that learning is embedded, allowing students to progressively build the ability to recognize, analyze, and address ethical dilemmas. Finally, the global movement towards competencies-based education, exemplified by WHO's competency guide for mental and neurological care, provides a replicable model for other domains, advocating for a framework that is adaptable to local contexts and resource settings without being a rigid, one-size-fits-all solution [9].

The globalization of health challenges, from pandemic diseases to disparities in healthcare access, necessitates a paradigm shift in how bioethics is taught to future medical professionals and researchers [14]. A "transplanted" curriculum, developed in one cultural or national context and directly applied in another, risks being ineffective and ethically problematic. It often fails to equip professionals with the nuanced understanding required to navigate the specific ethical dilemmas they will encounter in their local practice [3]. The core thesis of this whitepaper is that bioethics curriculum development must move beyond a one-size-fits-all model. Instead, it must embrace contextual relevance, a deliberate and systematic approach to curriculum design that integrates local cultural values, prevalent health issues, and specific regional ethical challenges into the core of educational content and pedagogy. This is not merely an educational preference but a fundamental component of ethical rigor, ensuring that the principles of autonomy, justice, and beneficence are interpreted and applied in a manner that is both globally informed and locally resonant [15] [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this contextual understanding is critical for conducting ethical global clinical trials, addressing issues of consent and equity, and ensuring that scientific advancements are implemented responsibly across diverse populations.

Quantitative Landscape of Bioethics Education Integration

A systematic mapping of the field reveals both the progress and the significant gaps in the institutionalization of bioethics. The following table summarizes data from a review of 444 articles on the integration of bioethics in higher education institutions.

Table 1: Institutionalization of Bioethics in Higher Education: A Systematic Analysis

| Aspect of Integration | Metric (%) | Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program Level Focus | Undergraduate: 40.5% | Postgraduate: 19.4% | A predominant focus on undergraduate education, with relatively less structured attention at postgraduate levels [15]. |

| Disciplinary Distribution | Health Sciences: 81.3% | Social Sciences, Humanities, Biological Sciences, Engineering: 18.7% | Bioethics education is heavily concentrated within the health sciences, indicating a need for greater interdisciplinary reach [15]. |

| Use of Active Methodologies & Ed-Tech | 21.4% | The integration of interactive tools and methods is a significant and growing trend, enhancing engagement and learning outcomes [15]. | |

| Research on Institutionalization | 10.3% | A critical lack of empirical studies documenting and validating the process of embedding bioethics within institutions [15]. | |

| Studies on Comparative/Replicated Practices | 2% | A severe deficit in comparative analyses or replicated studies, hindering the sharing of best practices across contexts [15]. |

Furthermore, evaluation studies of specific curricula provide data on educational effectiveness. A decade-long study of an integrated undergraduate medical bioethics curriculum utilized a mixed-methods approach to assess student achievement, gathering quantitative feedback from 500 students across a five-year program [3].

Table 2: Effectiveness of a Longitudinally Integrated Bioethics Curriculum (n=500 students)

| Domain of Achievement | Agreement among Students (%) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Acquisition | 60.3% - 71.2% | A majority of students confirmed the curriculum's role in expanding their understanding of bioethical principles and issues [3]. |

| Skill Development | 59.4% - 60.3% | Students reported development in critical skills, such as identifying and analyzing ethical dilemmas [3]. |

| Ethical & Professional Behavior | 62.5% - 67.7% | Students acknowledged the curriculum's contribution to their personal ethical positioning and professional conduct [3]. |

Theoretical Frameworks for Contextual Relevance

From Culturally Responsive to Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy

The development of a contextually relevant curriculum is underpinned by established pedagogical theories from general education, which have profound implications for bioethics. Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT), a term coined by Geneva Gay, is defined as using students' customs, characteristics, experiences, and perspectives as tools for better classroom instruction [16]. It is validating, comprehensive, multidimensional, empowering, transformative, and emancipatory [17]. This framework builds upon Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, introduced by Gloria Ladson-Billings, which rests on three propositions: student learning (intellectual growth), cultural competence (affirming one's culture of origin while developing fluency in others), and critical consciousness (the ability to identify and challenge societal inequities) [16] [17].

A more recent evolution is Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, which posits that students of color should not be expected to adhere to dominant cultural norms. Instead, their own cultural ways of being should be explored, honored, and nurtured by educators [16]. For bioethics, this means curricula should not simply "add" diverse perspectives but should actively sustain the cultural pluralism that students and their future patients bring to healthcare encounters.

Cosmopolitanism in Global Bioethics

Parallel to these pedagogical theories is the philosophical concept of cosmopolitanism in global bioethics. This perspective aims to further ideals of solidarity, equality, and respect for differences, educating health professionals in their role as 'citizens of the world' [14]. It argues that ethical discourse must first critique the structures of violence and injustice that underlie global health threats. A contextually relevant curriculum, therefore, is not parochial; it situates local ethical challenges within a global framework, enabling professionals to understand the transnational dimensions of issues like resource allocation, pandemics, and medical migration [14] [18].

Experimental and Methodological Protocols for Curriculum Development and Evaluation

Protocol 1: Mixed-Methods Curriculum Evaluation

Objective: To comprehensively assess the effectiveness, relevance, and integration of a bioethics curriculum within a specific institutional context [3].

Workflow:

- Phase 1 - Quantitative Data Collection: Distribute a structured online questionnaire to all student cohorts (e.g., Years 1-5 of a medical program). The questionnaire should be based on an evaluation model like CIPP (Context, Input, Process, Product) and use Likert scales to measure perceived relevance of content, effectiveness of teaching methods, and self-reported achievement in knowledge, skills, and professional behavior [3].

- Data Analysis: Analyze quantitative data to identify trends, strengths, and weaknesses. For example, calculate percentage agreement for key domains as shown in Table 2.

- Phase 2 - Qualitative Data Collection: Conduct Focus Group Discussions (FGDs):

- Separate FGDs with students from different stages of the curriculum (e.g., pre-clinical and clinical years).

- One FGD with faculty involved in teaching bioethics and clinical faculty who reinforce ethics in practice.

- Use semi-structured interview guides to explore quantitative findings in depth, asking about integration, practical application, and specific challenges [3].

- Data Analysis: Transcribe and thematically analyze FGD data to explain and enrich the quantitative results. Key themes might include the need for better clinical integration or the value of specific teaching methods.

- Triangulation and Reporting: Integrate findings from both phases to form a holistic understanding of the curriculum's performance and generate actionable recommendations for improvement [3].

Protocol 2: Digital Tool-Assisted, Discovery-Driven Research

Objective: To leverage educational technology (Ed-Tech) for both teaching bioethics and generating empirical data on the psychological and epistemic factors influencing moral judgment [19].

Workflow:

- Tool Development: Create a mobile application (e.g., "MyBioethics") containing modular lessons on various bioethical topics. Each lesson includes interactive dilemma scenarios [19].

- Data Generation Module:

- Users vote on the ethical alternative in a given scenario.

- Post-vote, users disclose their self-perceived moral certainty and the decisive ethical principle (e.g., autonomy, justice) that guided their choice from a provided list or a free-text field [19].

- The app integrates standardized psychometric and epistemometric surveys to measure users' dispositional tendencies (e.g., optimism, cognitive style) [19].

- Data Analysis: Employ quantitative and explorative data analysis to investigate correlations between users' measured psychological/epistemic traits and their expressed moral judgments. This methodology is hypothesis-generating, aiming to identify previously unarticulated factors behind ethical decision-making [19].

- Educational Feedback: The app provides users with personalized feedback, showing their survey results compared to averages and prompting reflection on how these traits might influence their ethical views. This closes the loop between research and learning [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Bioethics Education Research

Table 3: Key Methodological Tools for Curriculum Development and Evaluation

| Research 'Reagent' | Category | Function in Bioethics Education Research |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Questionnaire (CIPP Model) | Evaluation Framework | Provides a systematic structure (Context, Input, Process, Product) for developing questions to assess all aspects of a curriculum's implementation and impact [3]. |

| Likert Scale | Psychometric Tool | A reliable and replicable measurement instrument for capturing attitudes and perceptions on a quantitative scale (e.g., 1-5, Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree), allowing for statistical analysis of student and faculty feedback [3]. |

| Focus Group Discussion (FGD) Guide | Qualitative Instrument | A semi-structured protocol of open-ended questions used to facilitate in-depth group interviews, generating rich, explanatory data on participant experiences and perspectives [3]. |

| Interactive Dilemma Scenarios | Ed-Tech / Pedagogical Tool | Real-life or hypothetical case studies embedded in digital platforms to engage users, elicit moral judgments, and serve as a data source for analyzing decision-making patterns [19]. |

| Psychometric Surveys (e.g., for cognitive style) | Empirical Research Tool | Standardized questionnaires integrated into digital learning environments to measure psychological and epistemic constructs, enabling research into their correlation with ethical judgments [19]. |

| Systematic Mapping Methodology | Literature Review Protocol | A rigorous process for searching, selecting, and analyzing a broad range of literature to quantify the scope and identify gaps in a research field, such as the institutionalization of bioethics [15]. |

A Conceptual Workflow for Contextual Curriculum Design

The following diagram synthesizes the core principles and processes involved in moving from a transplanted to a contextually relevant bioethics curriculum.

Developing contextually relevant bioethics curricula is an empirical and iterative process, not a one-time event. The data and protocols presented provide a roadmap for researchers and educators. Future efforts must focus on strengthening the evidence base for curriculum implementation, particularly through comparative studies and a greater focus on postgraduate and interdisciplinary education [15]. The promising integration of active methodologies and educational technology, such as the MyBioethics app, points toward a future of more engaging, data-enriched, and personally relevant ethics education [19] [15]. For the global community of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, embracing this contextual paradigm is essential for fostering a generation of professionals who are not only technically proficient but also culturally competent and ethically astute citizens of the world, prepared to tackle the complex moral challenges of globalized health and science [14] [18].

The formal integration of bioethics into medical curricula represents a critical response to the complex moral challenges posed by rapid advancements in biomedical science and technology. As a discipline, bioethics serves as a branch of ethical inquiry that examines the nature of biological and technological discoveries and the responsible use of biomedical advances, with particular emphasis upon their moral implications for our individual and common humanity [20]. The evolution of medical practice, characterized by groundbreaking developments in genetics, neuroscience, and reproductive technologies, has necessitated a parallel evolution in ethics education to ensure medical professionals can navigate the attendant ethical dilemmas with moral clarity and analytical rigor.

This whitepaper establishes a foundational framework for bioethics curriculum development within medical schools, articulating 30 essential topics organized within a cohesive conceptual structure. The proposed taxonomy is designed to equip future physicians with the ethical reasoning competencies necessary for contemporary clinical practice, research integrity, and policy engagement. By surveying core concepts across clinical ethics, research ethics, foundational principles, and emerging technologies, this curriculum aims to address the documented gap between theoretical ethics and practical application that has been identified in medical education literature [7] [21]. The structured approach outlined herein provides medical educators with evidence-based guidance for developing comprehensive ethics education that spans the entire undergraduate medical curriculum, fostering the development of professionals who are not only clinically competent but also ethically discerning.

Essential Bioethics Topics: A Categorical Taxonomy

The following taxonomy organizes 30 essential bioethics topics into four interconnected domains, providing a systematic framework for curriculum development. This classification reflects the core competencies required for ethical medical practice and facilitates logical sequencing of educational content across a medical training program.

Table 1: Core Bioethics Topics for Medical Education

| Domain | Essential Topics |

|---|---|

| Clinical Ethics & Patient Care | 1. Informed Consent2. Confidentiality & Truth-Telling3. End-of-Life Care4. Physician-Assisted Suicide5. Organ Donation & Transplantation6. Allocation of Healthcare Resources7. Professional Boundaries8. Pediatric Ethics & Assent9. Capacity & Surrogate Decision-Making10. Cultural & Religious Competence |

| Research Ethics & Scientific Integrity | 11. Historical Context & Tragic Lessons12. Informed Consent in Research13. Protection of Vulnerable Populations14. Conflict of Interest15. Good Scientific Practice (GSP)16. Data Manipulation & Fabrication17. Authorship & Intellectual Property18. Plagiarism19. Research with Animals20. Compassionate Use of Experimental Drugs |

| Foundational Principles & Theories | 21. Major Ethical Theories (Deontology, Utilitarianism, Virtue Ethics)22. Principles of Bioethics (Autonomy, Beneficence, Non-maleficence, Justice)23. Moral Reasoning & Dilemma Resolution24. Human Dignity & What It Means to Be Human25. Justice and Fairness in Healthcare |

| Emerging Technologies & Special Populations | 26. Reproductive Technologies & Ethics27. Genetic Testing & Intervention (CRISPR)28. Stem Cell Research & Cloning29. Neuroscience & Psychopharmacology30. Gender Variance & Clinical Care |

This categorical framework enables spiral integration of bioethics throughout medical education, where basic principles introduced in pre-clinical years are reinforced and applied with increasing complexity during clinical training [7]. The taxonomy's structure acknowledges the interdisciplinary nature of bioethics, integrating diverse fields including life sciences, medicine, biotechnology, philosophy, theology, public policy, and law [20]. This approach ensures that graduates develop the analytical skills necessary to recognize, critically analyze, and address ethical dilemmas across the spectrum of medical practice, from bedside decisions to broader healthcare policy considerations.

Quantitative Assessment of Bioethics Education Outcomes

Empirical evaluation of bioethics curricula provides critical evidence for their educational impact and areas for improvement. A comprehensive mixed-methods study of an integrated bioethics curriculum delivered over five years in an undergraduate medical program yielded compelling quantitative data on student outcomes across three core competency domains [7].

Table 2: Bioethics Curriculum Effectiveness: Student Self-Assessed Competency Gains

| Competency Domain | Specific Learning Outcome | Agreement Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Acquisition | Understanding of ethical principles and concepts | 71.2 |

| Recognition of ethical dilemmas in clinical practice | 70.5 | |

| Knowledge of professional codes and guidelines | 60.3 | |

| Skill Development | Analytical skills for ethical dilemma resolution | 60.3 |

| Communication skills for ethics discussions | 59.4 | |

| Professional Behavior | Demonstration of ethical professional conduct | 67.7 |

| Application of ethical reasoning in clinical settings | 62.5 |

The data demonstrates that the curriculum was most effective in fostering knowledge acquisition, particularly in understanding ethical principles and recognizing dilemmas, while indicating potential areas for enhancement in skill development components [7]. This pattern suggests the need for increased experiential learning opportunities to bridge the theory-practice gap that often challenges ethics education.

Additional research on Good Scientific Practice (GSP) education reveals startling preliminary knowledge gaps among medical students, with one study showing approximately 25% of students initially unable to recognize forms of plagiarism prior to targeted instruction [22]. However, post-teaching assessment demonstrated statistically significant improvement (<0.0001), with incorrect answers dropping to 3.4%, confirming that structured ethics education effectively addresses these foundational knowledge deficits [22]. These findings underscore the essential role of formal bioethics training in establishing the ethical foundation necessary for both clinical practice and research activities.

Experimental Protocols in Bioethics Education Research

Mixed-Methods Curriculum Evaluation

The effectiveness of bioethics curricula can be rigorously assessed through a sequential explanatory design that combines quantitative and qualitative methodologies [7]. This mixed-methods approach provides comprehensive insights into both the measurable outcomes and experiential dimensions of ethics education.

Phase 1 - Quantitative Assessment: Implement a structured questionnaire administered to students across all years of the medical program (Years 1-5). The survey should utilize Likert-scale items to assess student perceptions of curriculum effectiveness in three domains: (1) knowledge acquisition, (2) skill development, and (3) demonstration of ethical/professional behavior. Employ multiple response rate maximization strategies, including online distribution via curriculum management software, protected time for completion during sessions, and hard copy availability [7].

Phase 2 - Qualitative Analysis: Conduct Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with separate student cohorts (Years 1-2 and Years 3-5) and faculty actively involved in bioethics teaching. Use semi-structured interview guides to explore: course content relevance, integration approaches, instructional method effectiveness, and challenges in theory-to-practice transition. Complement FGDs with document review of curriculum materials and student feedback to assess alignment between planned objectives and implementation reality [7].

This protocol employs the Context, Input, Process and Product (CIPP) model as an evaluative framework, focusing not only on whether the program is working but also identifying specific areas for improvement [7]. The model facilitates development of questions related to context (curriculum integration), input (content relevance), and process (teaching methodologies), enabling a comprehensive curriculum assessment.

Pre-Post Teaching Assessment with Case Vignettes

A specialized protocol for evaluating specific bioethics competencies employs a pre-post questionnaire design utilizing hypothetical case vignettes to assess knowledge and attitude transformation [22].

Instrument Development: Create three fictitious case vignettes, each representing a typical form of scientific misconduct or ethical challenge (e.g., plagiarism, data manipulation). For each vignette, develop assessment items measuring: (1) knowledge (4 dichotomous "yes/no" items), (2) attitudes (4 items using 5-point Likert scales from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree"), and (3) previous topic exposure (1 "yes/no" item) [22].

Implementation Protocol: Administer the pre-teaching questionnaire at the beginning of the first instructional session. Conduct the ethics course using a combination of theory-based lectures and practice-based case discussion rounds, employing problem-based learning (PBL) methodology with hypothetical case vignettes and analysis of core guidelines. Administer the identical post-teaching questionnaire at the conclusion of the instructional sequence, typically spanning 2-4 weeks [22].

Statistical Analysis: Apply appropriate statistical tests based on data distribution, utilizing McNemar test for paired categorical data and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normally distributed continuous data, with significance level set at p<0.05 [22].

This protocol provides robust quantitative data on ethics education effectiveness while simultaneously familiarizing students with the analytical processes essential to ethical reasoning in professional practice.

Conceptual Frameworks for Bioethics Education

Integrated Clinical Ethics Learning Pathway

The translation of theoretical ethics knowledge to clinical practice requires a structured pathway that connects educational content with practical application. The following framework visualizes this integrative process, from foundational knowledge to clinical competence.

This framework highlights the developmental progression from theoretical understanding to practical competence, emphasizing that ethical reasoning skills are built upon a foundation of core knowledge [7]. The pathway acknowledges that effective bioethics education requires both cognitive and practical components, with clinical application serving as the crucial bridge to professional competence.

Clinical Ethics Consultation Analysis System

Modern bioethics education increasingly incorporates empirical data and standardized analysis frameworks to enhance learning effectiveness. The Armstrong Clinical Ethics Coding System (ACECS) represents an innovative approach that transforms clinical ethics consultation data into educational content [21].

This system addresses a fundamental challenge in bioethics education: the theory-practice divide [21]. By utilizing actual clinical ethics data, it provides students with exposure to real-world ethical issues and patterns, enhancing the relevance and practical application of their learning. The interactive nature of the visual analytics dashboard facilitates exploration of ethical issue frequency, relationships, and contextual factors, supporting the development of pattern recognition skills essential for clinical ethics practice [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for Bioethics Education

The following toolkit comprises essential methodological approaches and conceptual frameworks that serve as fundamental "reagents" for effective bioethics education and research.

Table 3: Essential Methodologies and Analytical Frameworks for Bioethics Education

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Four-Box Method | Structured case analysis framework | Clinical ethics decision-making; organizes considerations into medical indications, patient preferences, quality of life, and contextual factors [23] |

| ACECS Coding System | Standardized consultation documentation | Ethics consultation analysis; enables systematic categorization of case types, participants, complexity, and ethical issues [21] |

| Problem-Based Learning (PBL) | Student-centered case-based pedagogy | Classroom instruction; uses hypothetical and real cases to foster analytical skills and ethical reasoning [22] |

| Visual Analytics Dashboard | Interactive data visualization | Curriculum development; identifies patterns in ethics consultation data to inform educational priorities [21] |

| CIPP Evaluation Model | Comprehensive curriculum assessment | Program evaluation; assesses context, input, process, and product dimensions of ethics curricula [7] |

| Sequential Explanatory Design | Mixed-methods research methodology | Curriculum research; combines quantitative and qualitative data for comprehensive program assessment [7] |

These foundational resources enable the systematic implementation and rigorous evaluation of bioethics educational programs. The Four-Box Method, in particular, serves as a widely-adopted analytical framework for clinical ethics case analysis, providing a structured approach to organizing and balancing the diverse considerations inherent in ethical dilemmas [23]. Meanwhile, the ACECS system addresses the critical need for standardized documentation and analysis of ethics consultations, creating a robust empirical foundation for education that reflects actual clinical practice [21].

The 30 essential topics and conceptual frameworks presented in this whitepaper provide a comprehensive blueprint for developing robust bioethics curricula within medical education. The categorical taxonomy spans the critical domains of clinical ethics, research integrity, foundational principles, and emerging technologies, collectively addressing the full spectrum of ethical challenges confronting contemporary medical professionals. This structured approach facilitates the longitudinal integration of ethics education throughout medical training, from pre-clinical instruction through clinical clerkships, ensuring sustained engagement with ethical principles and their practical application.

The quantitative evidence and methodological protocols outlined demonstrate that effective bioethics education requires both theoretical foundation and practical application. As the field continues to evolve in response to technological advancements and societal changes, bioethics curricula must remain dynamic, incorporating empirical data from clinical ethics consultation services and adapting to emerging ethical challenges [21]. The tools and frameworks presented—from the Four-Box Method for case analysis to innovative approaches like the ACECS coding system—provide medical educators with evidence-based resources for developing ethics education that truly prepares graduates for the moral dimensions of medical practice. By implementing such comprehensive bioethics curricula, medical schools can fulfill their essential responsibility to develop professionals capable of navigating the complex ethical terrain of modern healthcare with wisdom, compassion, and moral clarity.

The development of a robust ethical framework is a cornerstone of medical education, essential for preparing clinicians capable of navigating complex moral dilemmas in healthcare. Traditional approaches to ethics education often involved standalone courses or sporadic lectures, which proved insufficient for fostering the deep integration of ethical reasoning into clinical practice. The spiral curriculum model, first conceptualized by Jerome Bruner, offers a transformative alternative by enabling iterative revisiting of core topics with increasing complexity throughout the educational journey [24]. This pedagogical approach recognizes that ethical development is not a singular event but a longitudinal process that evolves with clinical exposure and maturity [25].

In medical education, the spiral curriculum provides the structural foundation for integrating bioethics across a five-year program, ensuring that basic principles introduced in pre-clinical years are reinforced, deepened, and applied in increasingly complex clinical scenarios [3] [26]. This whitepaper examines the implementation, efficacy, and methodological considerations of spiral ethics curricula in undergraduate medical education, drawing upon recent empirical studies to provide a framework for curriculum developers and researchers. By synthesizing quantitative outcomes and qualitative insights from programs implemented in diverse geographical contexts, this analysis aims to establish evidence-based guidelines for optimizing ethics education in medical training.

Theoretical Foundations of the Spiral Curriculum

The spiral curriculum is predicated on cognitive theories advanced by Jerome Bruner, who hypothesized that "any subject can be taught in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development" [24]. This approach challenges linear curriculum models by emphasizing iterative engagement with core concepts at progressively sophisticated levels. Three fundamental principles characterize the spiral curriculum: (1) students revisit topics, themes, or subjects multiple times throughout their educational career; (2) the complexity of the topic increases with each revisit; and (3) new learning continuously relates to and contextualizes previous knowledge [24] [27].

In medical ethics education, this theoretical framework translates to a structured recurrence of ethical concepts across the curriculum, with each encounter building upon previous knowledge while introducing new dimensions appropriate to the learner's clinical experience. The spiral model stands in contrast to non-linear curriculum models that may be better suited to knowledge domains with less structured knowledge domains, such as arts and humanities [27]. Medical ethics, with its foundation in philosophical principles that apply to increasingly complex clinical scenarios, aligns well with the spiral approach's structured progression from simplistic ideas to complicated applications [3] [26].

Table 1: Key Principles of the Spiral Curriculum in Medical Ethics Education

| Principle | Theoretical Basis | Application in Ethics Education |

|---|---|---|

| Iterative Revisiting | Cognitive reinforcement through repeated exposure | Core ethical principles reintroduced in multiple contexts across years |

| Progressive Complexity | Bruner's concept of intellectual development | Basic principles in pre-clinical years advance to complex dilemmas in clinical years |

| Contextual Relationship | Constructivist learning theory | New ethical learning connected to previous knowledge through clinical applications |

Implementation Framework: A Four-Dimensional Model for Ethics Integration

Implementing a spiral curriculum for ethics education requires deliberate structuring across the entire medical program. A recently proposed four-dimensional model offers a comprehensive framework for integrating ethics and professionalism throughout an integrated medical curriculum [26]. This model ensures students learn ethics progressively and apply its principles spontaneously in clinical settings.

The first dimension involves the insertion of ethics issues within modules as part of student-centered activities such as problem-based learning (PBL), case-based learning (CBL), team-based learning (TBL), and hospital-based teaching (HBT). For example, ethical issues related to research are embedded within research methodology modules, while ethical issues of assisted reproduction are integrated into reproductive medicine and women's health curricula [26].

The second dimension consists of structured ethics topics inserted into appropriate modules across all phases of the program. This ensures dedicated attention to fundamental ethical concepts while maintaining their relevance to concurrent coursework.

The third dimension involves implementing a condensed ethics module in the fourth year, which serves to consolidate and synthesize ethical principles before students enter intensive clinical training. This concentrated exposure reinforces previous learning while introducing more nuanced considerations.

The fourth dimension establishes a practice-based ethics course during the internship period, where students encounter ethical issues initially through CBLs and subsequently through direct application with real patients in diverse healthcare situations [26]. This multidimensional approach creates a seamless ethics education trajectory that begins with fundamental principles and culminates in autonomous ethical decision-making.

Table 2: Four-Dimensional Model for Spiral Ethics Curriculum Implementation

| Dimension | Educational Phase | Teaching Modalities | Learning Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Embedded Ethics Issues | Years 1-5 | PBL, CBL, TBL, HBT | Contextual application in relevant clinical topics |

| 2: Structured Ethics Topics | Years 1-5 | Dedicated sessions within modules | Foundational knowledge and principle recognition |

| 3: Condensed Ethics Module | Year 4 | Intensive workshops | Synthesis and consolidation of ethical principles |

| 4: Practice-Based Ethics | Internship | CBLs, clinical rotations | Autonomous application in real healthcare settings |

Quantitative Outcomes: Efficacy of Spiral Ethics Curricula

Empirical evidence demonstrates the effectiveness of spiral ethics curricula in developing knowledge, skills, and professional behaviors in medical students. A comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation of a bioethics curriculum integrated across a five-year undergraduate medical program revealed significant positive outcomes across multiple domains [3] [4].

Quantitative data collected through structured questionnaires administered to students across all years of the program indicated that the majority of students agreed the spiral curriculum contributed substantially to their ethical development. Specifically, 60.3-71.2% of students reported enhanced knowledge acquisition, 59.41-60.30% acknowledged improvement in ethical reasoning skills, and 62.54-67.65% recognized development in demonstrating ethical and professional behavior [3]. These quantitative measures demonstrate consistent positive outcomes across the cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains of learning.

The study employed a mixed methods sequential explanatory design, with quantitative data gathered through structured online questionnaires followed by qualitative data collection through focus group discussions and document review [3]. This methodological approach allowed for comprehensive program evaluation beyond mere satisfaction metrics, capturing substantive learning outcomes across the five-year program.

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes of Spiral Ethics Curriculum Implementation

| Learning Domain | Student Agreement (%) | Key Measured Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Acquisition | 60.3 - 71.2% | Understanding ethical principles, recognition of dilemmas |

| Skill Development | 59.41 - 60.30% | Ethical analysis, moral reasoning, decision-making |

| Professional Behavior | 62.54 - 67.65% | Demonstration of ethical conduct in clinical settings |

Methodological Considerations for Curriculum Evaluation

Rigorous assessment of spiral ethics curricula requires methodological approaches capable of capturing both quantitative outcomes and qualitative insights into the educational process. The mixed methods sequential explanatory design employed in recent studies offers a robust framework for comprehensive curriculum evaluation [3].

In the quantitative phase, researchers utilized a structured online questionnaire administered to 500 students across years 1-5 of the medical program. The questionnaire was developed based on the Context, Input, Process and Product (CIPP) model, which focuses not only on whether the program is working but also identifies areas for improvement [3]. This model facilitated the development of questions related to context (integration in curriculum), input (clarity and relevance of content), and process (teaching methods, assessment, student engagement).

The qualitative phase employed focus group discussions (FGDs) with students and faculty, along with document review, to explain and enrich the quantitative findings [3]. Semi-structured interview guides for FGDs focused on course contents, integration, instructional methods, transition from theory to practice, and student achievement across knowledge, skills, and attitude domains. Faculty FGDs addressed integration, student engagement, course content, methods, assessment, and implementation challenges.

This methodological approach allowed researchers to triangulate findings, with qualitative data providing context and explanation for quantitative results. For instance, while quantitative data indicated overall positive outcomes, qualitative insights revealed specific implementation challenges, such as the need for better integration in clinical years and more opportunities for application in healthcare settings [3].

Instructional Modalities and Pedagogical Approaches

Effective implementation of spiral ethics curricula requires diverse instructional modalities aligned with students' evolving learning needs across the educational continuum. Research indicates that multi-modal instructional methods are particularly effective for ethics education, with student and faculty responses highlighting the value of interactive, engaging approaches [3].

Small group teaching and shorter sessions were identified as preferable formats for fostering discussion and maintaining student engagement and attention [3]. These intimate learning environments facilitate the dialogue and reflection essential for ethical development. In contrast, large class formats were generally perceived as less effective for ethics education, suggesting the importance of personalized interaction in moral development.

Studies highlight the effectiveness of problem-based learning within spiral curricula, using real-life cases and contextually relevant scenarios to facilitate contextual understanding and application of knowledge [3]. In the early years, the content appropriately blends moral philosophy with applied clinical ethics, employing teaching methods that include lectures, discussions, brainstorming, problem-solving exercises, videos/movies, and case studies [3].

As students progress to clinical years, ethics education becomes integrated within clerkships and offered as workshops alongside related topics like gender, culture, and communication [3]. This progression from theoretical foundations to clinical application embodies the spiral approach, reinforcing previously introduced concepts while adding complexity and context-specific considerations.

Digital Infrastructure and Learning Management Systems

The successful implementation of a spiral curriculum requires thoughtful technological support, particularly through Learning Management Systems (LMS) that facilitate students' ability to revisit and build upon previous learning. Research conducted at the University of Cape Town revealed that 70% of medical students revisited previous online courses, primarily to review lecture presentations, lecture notes, and quizzes [28].

This study demonstrated that students perceived significant benefits from maintaining access to previous course materials, particularly for understanding new material, preparation for assessments, and convenience [28]. Although student comments did not always explicitly reference the spiral curriculum, most described processes of building on previous work, with some specifically mentioning the spiral nature of their learning.

These findings have important implications for LMS implementation in medical education. The common practice of archiving and replacing previous online courses may inadvertently hinder the spiral learning process by removing essential reference materials that students use to connect new learning to previous knowledge [28]. Instead, institutions should consider maintaining student access to previous years' course materials to support the iterative revisiting inherent in the spiral approach.

The digital infrastructure should be designed to mirror and support the face-to-face spiral curriculum, with careful attention to how online resource organization either facilitates or impedes students' ability to trace the development of ethical concepts across their educational journey. This alignment between pedagogical philosophy and technological implementation is essential for realizing the full potential of the spiral curriculum model.

Challenges and Implementation Barriers

Despite its theoretical strengths and demonstrated efficacy, implementing spiral ethics curricula presents significant challenges that require strategic addressing. Research identifying a "broken spiral" phenomenon highlights how students may struggle when introduced to more complex new topics without having mastered previous foundational concepts [29].

Studies of spiral curriculum implementation in various contexts reveal several common barriers. Teachers often struggle with the pacing of new concepts, with average instructional time across a year sometimes amounting to less than 30 minutes for 70% of topics [30]. This insufficient exposure time compromises mastery development, essential for the spiral approach. Additional challenges include curriculum congestion, inadequate review periods, and variations in teachers' content knowledge and mastery, all of which impact curriculum continuity [30] [29].

In ethics education specifically, participants have identified needs for better integration in clinical years, enhanced role modeling, and more opportunities for application in clinical healthcare settings [3]. Additionally, both students and faculty have suggested expanding curriculum content to include emerging ethical topics such as ethical issues related to social media use, public health ethics, and the intersection of ethics and law [3].

Faculty development represents another critical challenge, as effective spiral curriculum implementation requires teachers to understand both the philosophical foundations of the approach and its practical application across year levels. Without adequate faculty buy-in and training, the intended spiral progression may fail to materialize in student learning experiences.

Table 4: Essential Methodological Resources for Spiral Ethics Curriculum Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Approaches | Application in Curriculum Development |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Frameworks | CIPP Model (Context, Input, Process, Product) | Comprehensive curriculum assessment across multiple dimensions |

| Research Designs | Mixed Methods Sequential Explanatory Design | Integration of quantitative outcomes with qualitative insights |

| Data Collection Methods | Structured questionnaires, Focus Group Discussions, Document Review | Triangulation of data sources for robust evaluation |

| Assessment Modalities | Portfolios, Ethical Reasoning Assessments, Behavioral Observations | Longitudinal tracking of ethical development |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Bruner's Spiral Curriculum, Constructivist Learning Theory | Philosophical foundation for curriculum structure |

Future Directions and Research Agenda

The evolution of spiral ethics curricula in medical education necessitates continued research and innovation. Several promising directions emerge from current literature. First, establishing Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) in ethics would provide concrete milestones for assessing students' readiness for increasingly independent ethical decision-making [25]. These EPAs could be mapped to specific points in the spiral curriculum, creating clear developmental trajectories.

Second, further exploration of portfolio-based assessment offers potential for capturing the longitudinal development of ethical reasoning and professional identity formation [25]. Portfolios can document the iterative deepening of ethical understanding central to the spiral approach, providing rich data for both assessment and research.