Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Interdisciplinary Methods in Empirical Bioethics for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of interdisciplinary approaches in empirical bioethics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Interdisciplinary Methods in Empirical Bioethics for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of interdisciplinary approaches in empirical bioethics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It addresses the foundational need to integrate empirical data with normative analysis, moving beyond traditional philosophical inquiry to ground ethical guidance in the realities of clinical practice and research. The scope covers established methodological frameworks for combining qualitative and quantitative research with ethical reasoning, tackles common challenges such as interdisciplinary conflict and the 'is-ought' gap, and evaluates the rigor and acceptability of different approaches. By synthesizing current methodologies and their practical applications, this guide aims to equip professionals with the tools to conduct robust, ethically-informed research that can effectively navigate the complexities of modern healthcare innovations.

The 'Is' and the 'Ought': Laying the Groundwork for Empirical Bioethics

Interdisciplinary Empirical Bioethics (IEB) represents a significant methodological evolution within bioethics, emerging from the concerted effort to bridge the gap between theoretical normative analysis and the lived reality of ethical issues in healthcare, medicine, and science [1]. This field is fundamentally characterized by its integration of empirical research methods from the social sciences—such as sociology, anthropology, and psychology—with the normative analytical frameworks of philosophy and law [2] [3]. The rise of IEB is often attributed to a dissatisfaction with a purely philosophical approach, which was perceived as insufficient to address the complex, context-specific nature of bioethical issues encountered in practice [2]. By systematically incorporating data about the actual beliefs, behaviors, and experiences of relevant stakeholders, IEB seeks to ground ethical analysis in a richer, more nuanced understanding of the practical contexts in which ethical dilemmas arise [4].

The "interdisciplinary" component is crucial; it moves beyond a mere multidisciplinarity where different disciplines work in parallel, and instead fosters a integrative dialogue where empirical findings and normative reasoning mutually inform and reshape one another [5]. This integration aims to produce ethical recommendations that are not only philosophically sound but also practically relevant and applicable [6]. The empirical "turn" in bioethics has been substantial. Surveys of bioethics researchers in twelve European countries found that 87.5% report using or having used empirical methods in their work, indicating a widespread adoption of this interdisciplinary approach [3]. This article outlines the core frameworks, methodologies, and practical protocols that define and guide research in this dynamic field.

Theoretical Frameworks and Classifications

The theoretical foundation of IEB is built upon various models that classify its ambitions and describe the process of integrating empirical data with normative analysis. These frameworks help to structure research projects and clarify the intended contribution of empirical work to bioethical discourse.

Hierarchical Aims of Empirical Bioethics

One influential framework classifies the objectives of empirical research in bioethics into a hierarchy of four levels, ranging from the purely descriptive to the directly normative [6]. This classification helps to map the diverse ambitions of IEB projects, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Kon's Hierarchical Framework for Empirical Research in Bioethics

| Category | Description | Exemplary Research Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Lay of the Land | Seeks to define current practices, opinions, beliefs, or other aspects of the status quo [6]. | "What do patients want regarding Z?" "How do nurses perceive Y?" [6]. |

| Ideal vs. Reality | Assesses the extent to which actual clinical or research practice reflects established ethical ideals or norms [6]. | "To what extent is valid informed consent obtained in clinical trials?" "Do healthcare resources get allocated equitably?" [6]. |

| Improving Care | Uses empirical research to develop and test interventions aimed at bringing practice closer in line with ethical ideals [6]. | "Does a new ethics consultation service improve the alignment of care with patient values?" |

| Changing Ethical Norms | Brings together data from multiple empirical studies to inform, critique, and potentially change our ethical ideals and principles [6]. | "Do findings from long-term studies on quality of life compel a re-evaluation of norms surrounding life-sustaining treatment?" |

Recent empirical research on the views of IEB scholars themselves reveals nuanced attitudes towards these objectives. While identifying ethical issues in practice and understanding their context receives nearly unanimous agreement, objectives like "developing and justifying moral principles" are more contested, reflecting ongoing philosophical debates about the is-ought gap [4]. This gap, however, is increasingly viewed not as an insurmountable obstacle but as a warning sign to critically reflect on the normative implications of empirical results [4].

The Mapping-Framing-Shaping Process Framework

A complementary framework conceptualizes the entire IEB research process through a landscaping metaphor of Mapping-Framing-Shaping [5]. This model is particularly useful for designing and planning research projects.

- Mapping: This initial phase involves surveying the existing terrain of a bioethical issue. The researcher conducts comprehensive literature reviews, analyzing previous scholarship from relevant disciplines to understand the "state of the art," identify gaps, and hone research questions. It is primarily a desk-based, analytical stage [5].

- Framing: In this phase, the researcher zooms in to explore specific areas of the mapped terrain in depth. This typically involves qualitative empirical work (e.g., interviews, focus groups) to understand how key issues are "framed" and experienced by relevant stakeholders (e.g., patients, clinicians, researchers). The goal is to gather finely-grained, perspectival data on the lived experience of the ethical problem [5].

- Shaping: The final phase involves seeking to (re)shape the terrain by formulating normative recommendations. Informed by the findings from both the mapping and framing phases, the researcher develops a justified vision for a way forward, issuing guidance, policy recommendations, or theoretical corrections [5].

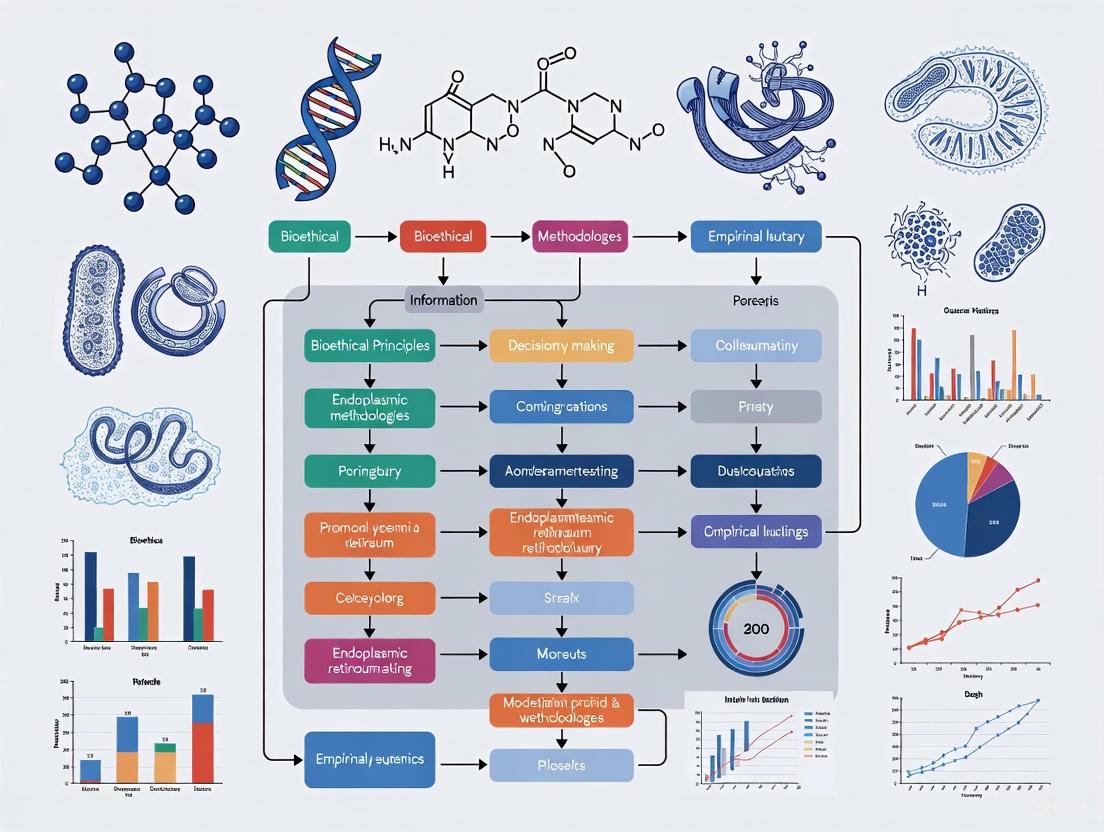

This framework underscores that integration is not a single event but a process that spans the entire research project, with each phase building upon the last [5]. The following diagram illustrates this workflow and its iterative nature.

Methodological Integration: Protocols and Practices

The defining challenge of IEB is the methodological integration of empirical data with normative analysis. This process must be transparent and rigorous to produce credible results.

Common Integration Methodologies

A systematic review has identified at least 32 distinct methodologies for integration, which can be grouped into several categories [2]:

- Consultative Approaches: The researcher acts as the sole integrator, analyzing empirical data and independently developing a normative conclusion. The most prominent example is Reflective Equilibrium, a process where the researcher engages in a back-and-forth deliberation between ethical principles, intuitions, and empirical facts until a state of coherence ("equilibrium") is achieved [4] [2].

- Dialogical Approaches: Integration occurs through structured dialogue among stakeholders (e.g., researchers, participants, professionals). In these methods, the normative conclusion is developed collectively through deliberation, with the ethicist often acting as a facilitator rather than the sole authority [2].

- Inherent Integration Approaches: In some projects, the normative and empirical are intertwined from the outset, with the research design making it difficult to separate the two components [2].

Despite this variety, scholars report that the practical application of these methodologies is often characterized by an "air of uncertainty and overall vagueness" [2]. This highlights the need for clear protocols and standards of practice.

A Protocol Template for Empirical Bioethics Research

To ensure scientific rigor and ethical soundness, IEB research should be guided by a structured protocol. The following table adapts a template specifically designed for humanities and social sciences in health, making it suitable for IEB projects [7].

Table 2: Core Elements of a Research Protocol for Interdisciplinary Empirical Bioethics

| Section | Key Content and Considerations for IEB |

|---|---|

| Title & Abstract | Clearly describe the nature of the study and the interdisciplinary approach used (e.g., "a qualitative empirical bioethics study using reflective equilibrium") [7]. |

| Problem & Rationale | Explain the importance of the bioethical problem and justify the need for an interdisciplinary approach, summarizing key scholarly work [7] [8]. |

| Objectives/Questions | Present specific, answerable research questions. IEB questions often have both an empirical and a normative component (e.g., "How do oncologists experience moral distress in early-phase trials, and what should be done to address it?"). |

| Disciplinary Field & Research Paradigm | Explicitly state the project's location in IEB. Present and justify the methodological framework (qualitative/quantitative/mixed) and the theoretical normative framework (e.g., principlism, care ethics) that will be used [7]. |

| Methodology: Data Collection | Detail the procedures for sampling participants, data collection (e.g., interview guides, surveys), and data management. Justify all choices in relation to the research questions [7] [8]. |

| Methodology: Integration & Normative Analysis | This is a crucial, defining section. Clearly articulate and justify the chosen method for integrating empirical data with normative analysis (e.g., reflective equilibrium, a dialogical approach). Explain how this process will be conducted [2] [5]. |

| Ethical Considerations | Describe issues like informed consent, confidentiality, and management of psychosocial risks. Even studies using only interviews or questionnaires must undergo ethics review [7] [9] [8]. |

This protocol structure ensures that researchers plan for integration from the beginning, rather than treating it as an afterthought.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Conducting robust IEB requires a toolkit composed of both conceptual "reagents" and practical methodological skills. The following table details key components.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Interdisciplinary Empirical Bioethics Research

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in IEB Research |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guides | Data Collection Instrument | Elicits rich, qualitative data on stakeholder perspectives, experiences, and moral reasoning while allowing for flexibility to explore unanticipated themes [3]. |

| Validated Survey Instruments | Data Collection Instrument | Quantifies attitudes, beliefs, or prevalence of practices across a larger population, providing data for "Lay of the Land" or "Ideal vs. Reality" studies [6] [3]. |

| Focus Group Protocols | Data Collection Instrument | Facilitates the collection of data through group interaction, revealing shared views, cultural norms, and points of contention on a bioethical issue [3]. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo, MAXQDA) | Data Analysis Tool | Assists in the systematic organization, coding, and analysis of large volumes of qualitative data (e.g., interview transcripts) [2]. |

| Reflective Equilibrium | Integration Methodology | Provides a structured, consultative process for the researcher to critically move back-and-forth between empirical data, ethical principles, and intuitive judgements to achieve normative coherence [4] [2]. |

| Deliberative Dialogues | Integration Methodology | Creates a structured forum for stakeholders to discuss empirical findings and ethical arguments, aiming to produce ethically robust and shared recommendations [2]. |

| Ethical Theory Framework (e.g., Principlism) | Normative Analytic Tool | Provides a coherent set of concepts and principles (e.g., autonomy, beneficence) to systematically analyze the ethical dimensions of the issue under study [7]. |

The effectiveness of these tools is contingent upon researcher competence. Surveys indicate a training gap, with over a fifth of bioethics researchers using empirical methods reporting no formal methodological training [3]. This underscores the need for interdisciplinary education that combines empirical research skills with normative analytical expertise.

Emerging Frontiers: Digital Bioethics

The digital transformation of society has given rise to a novel frontier in IEB: digital bioethics. This emerging sub-field leverages methods from computational social science to study bioethical issues as they are articulated and debated in online spaces [1]. Digital bioethics treats the online space—social media platforms, forums, and other digital agoras—as a legitimate site for rigorous empirical research in bioethics [1].

The methods of digital bioethics include:

- Automated analysis of hyperlink structures to map networked relationships between websites discussing bioethical issues.

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) to trace the emergence and evolution of bioethical discourse and public attitudes at scale.

- Digital ethnography to understand the cultures and practices that form around bioethical issues in virtual worlds and online communities [1].

This "digital turn" expands the empirical gaze of bioethics, allowing researchers to investigate how ethical issues are framed by the public and various stakeholders in real-time, offering new avenues for understanding the societal shaping of bioethical dilemmas [1]. The following diagram outlines the workflow of a typical digital bioethics study.

Interdisciplinary Empirical Bioethics is a maturing field that systematically integrates social science research with normative analysis to address complex ethical challenges in science and medicine. Its strength lies in its methodological commitment to grounding ethical reflection in a deep understanding of real-world contexts, stakeholder experiences, and empirical facts. While theoretical frameworks like Kon's hierarchy and the Mapping-Framing-Shaping process provide structure, the field's vitality comes from its practical, method-driven approach. The ongoing development of detailed protocols, together with the critical adoption of novel methods from fields like computational social science, ensures that IEB will continue to enhance the relevance, rigor, and impact of bioethics research. For researchers and drug development professionals, engaging with these methodologies offers a powerful means to ensure that ethical guidance is not only philosophically sound but also practically applicable and responsive to the complexities of modern science and healthcare.

Empirical bioethics has emerged as a critical interdisciplinary field that integrates empirical research with normative analysis to address complex ethical challenges in healthcare and biomedicine [2]. This field navigates the traditional philosophical tension between "is" (empirical facts) and "ought" (ethical norms) by developing systematic approaches to connect descriptive research with normative conclusions [6] [10]. The growth of empirical methods in bioethics has been substantial, with one analysis of nine major bioethics journals demonstrating a significant increase in empirical research publications from 5.4% in 1990 to 15.4% in 2003 [11].

This application note presents a four-stage hierarchical model for conceptualizing and conducting empirical bioethics research. The framework progresses from fundamental descriptive studies through increasingly sophisticated research that directly engages with ethical norms [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this hierarchy provides a structured methodology for designing studies that effectively integrate empirical findings with ethical analysis, ensuring research remains both scientifically rigorous and ethically relevant.

The model addresses a fundamental challenge in interdisciplinary bioethics research: the need for clear methodologies that bridge the empirical-normative divide [2] [10]. By providing a structured pathway from observation to normative recommendation, the framework enables more systematic and transparent empirical bioethics research that can effectively inform both clinical practice and policy development in pharmaceutical and medical research.

Theoretical Framework: Competence and Research Progression

The Four Stages of Competence Learning Model

The psychological process of acquiring new skills through progressive stages provides a valuable framework for understanding research development in empirical bioethics. The Four Stages of Competence model, originally developed in the 1960s, describes the psychological states involved in progressing from incompetence to competence in any skill [12] [13]. This model comprises four distinct stages:

- Stage 1: Unconscious Incompetence - The individual does not understand or know how to do something and does not recognize the deficit

- Stage 2: Conscious Incompetence - Though the individual does not understand or know how to do something, they recognize the deficit and the value of new skills

- Stage 3: Conscious Competence - The individual understands or knows how to do something but requires conscious effort and concentration to execute the skill

- Stage 4: Unconscious Competence - The skill has become "second nature" and can be performed easily, often while executing another task [12] [14]

When applied to empirical bioethics research methodology, this competence model mirrors the researcher's journey from recognizing methodological limitations to achieving integrative mastery in combining empirical and normative approaches.

The Four-Stage Research Hierarchy

Parallel to the competence model, empirical bioethics research can be conceptualized through a four-stage hierarchical framework that progresses from basic description to normative engagement [6]. This research hierarchy provides a systematic approach to interdisciplinary inquiry:

- Stage 1: Lay of the Land - Foundational studies mapping current practices, opinions, beliefs, or status quo

- Stage 2: Ideal Versus Reality - Investigates the alignment between ethical ideals and actual clinical practice

- Stage 3: Improving Care - Develops and tests interventions to bridge gaps between ideal and actual practice

- Stage 4: Changing Ethical Norms - Synthesizes empirical findings to inform and potentially modify ethical norms [6]

The relationship between these frameworks can be visualized through the following competence-research alignment diagram:

Competence-Research Alignment Diagram

Quantitative Landscape of Empirical Bioethics Research

Growth of Empirical Research in Bioethics

The integration of empirical methods into bioethics has steadily increased over recent decades. Analysis of peer-reviewed literature reveals significant trends in publication patterns and methodological approaches. The following table summarizes the prevalence of empirical research in major bioethics journals between 1990-2003:

Table 1: Prevalence of Empirical Research in Bioethics Journals (1990-2003)

| Journal | Total Articles | Empirical Studies | Percentage | Primary Research Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing Ethics | 367 | 145 | 39.5% | Clinical ethics, patient-provider relationships |

| Journal of Medical Ethics | 762 | 128 | 16.8% | Physician practices, institutional ethics |

| Journal of Clinical Ethics | 604 | 93 | 15.4% | Clinical decision-making, ethics consultation |

| Bioethics | 333 | 22 | 6.6% | Theoretical empirical integration |

| Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics | 287 | 19 | 6.6% | Healthcare policy, organizational ethics |

| Hastings Center Report | 487 | 10 | 2.1% | Policy analysis, ethical frameworks |

| Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics | 287 | 9 | 3.1% | Methodological discussions |

| Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal | 287 | 6 | 2.1% | Philosophical bioethics |

| Christian Bioethics | 287 | 3 | 1.0% | Religious perspectives in bioethics |

| Total/Average | 4029 | 435 | 10.8% |

Data adapted from [11]

The period from 1997-2003 showed a statistically significant increase (χ² = 49.0264, p<.0001) in empirical studies (n=309) compared to 1990-1996 (n=126) [11]. This trend has likely continued, reflecting growing acceptance of empirical approaches in bioethics.

Methodological Approaches and Research Topics

Empirical bioethics research employs diverse methodological approaches, with particular dominance of certain paradigms and subject areas:

Table 2: Methodological Approaches and Research Topics in Empirical Bioethics

| Research Characteristic | Frequency | Percentage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methodological Paradigm | |||

| Quantitative Methods | 281 | 64.6% | Surveys, structured observations |

| Qualitative Methods | 154 | 35.4% | Interviews, focus groups, ethnography |

| Primary Research Subjects | |||

| Healthcare Providers | 187 | 43.0% | Physicians, nurses, other clinicians |

| Patients | 153 | 35.2% | Patients, family members |

| Policy-makers/Institutions | 95 | 21.8% | Administrators, policy documents |

| Primary Research Topics | |||

| Prolongation of Life and Euthanasia | 68 | 15.6% | End-of-life decision making |

| Informed Consent | 59 | 13.6% | Consent processes, understanding |

| Patient Autonomy and Rights | 57 | 13.1% | Decision-making, preferences |

| Research Ethics | 49 | 11.3% | IRB processes, participant protection |

| Professional Ethics | 47 | 10.8% | Codes of conduct, professionalism |

| Resource Allocation | 42 | 9.7% | Priority setting, rationing |

Data synthesized from [11]

Most empirical studies (64.6%) employed quantitative methodologies, while qualitative approaches accounted for 35.4% of studies [11]. This distribution reflects different epistemological traditions and research questions within the field.

Stage 1: Lay of the Land Research

Protocol for Descriptive Foundational Studies

Objective: To establish baseline understanding of current practices, opinions, beliefs, or behaviors related to a specific bioethical issue.

Methodology:

- Research Design: Cross-sectional surveys, systematic documentation, qualitative interviews, or observational studies

- Sampling Strategy: Purposeful or representative sampling of relevant stakeholders (patients, providers, administrators)

- Data Collection: Structured instruments (surveys, questionnaires) or semi-structured approaches (interview guides, observation protocols)

- Analysis Plan: Descriptive statistics for quantitative data; thematic analysis for qualitative data

Application Example: Mapping hospital ethics committee composition and function through structured surveys of committee chairs and members [6]. This research documents variation in committee structure, case volume, consultation processes, and policy development roles.

Key Outputs:

- Baseline data on current states and practices

- Identification of patterns and variations

- Foundation for subsequent hypothesis-driven research

Implementation Framework

The workflow for Stage 1 research follows a systematic process from conceptualization to dissemination:

Stage 1 Research Workflow

Stage 2: Ideal Versus Reality Research

Protocol for Gap Analysis Studies

Objective: To assess the alignment between accepted ethical ideals/norms and actual clinical or research practices.

Methodology:

- Research Design: Comparative analysis, audit studies, or mixed-methods approaches

- Normative Framework Identification: Explicit statement of ethical norms or ideals being evaluated

- Data Collection: Direct observation, chart review, or participant reporting of actual practices

- Analysis Plan: Comparison between ideal standards and observed practices with gap characterization

Application Example: Investigating disparities in healthcare delivery by comparing treatment patterns across racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups [6]. This research begins with the ethical premise of equitable care and measures deviations from this ideal.

Key Outputs:

- Documentation of practice-norm misalignments

- Quantification of implementation gaps

- Identification of systemic barriers to ethical practice

Implementation Framework

Stage 2 research requires parallel tracking of normative standards and empirical observations:

Stage 2 Research Workflow

Stage 3: Improving Care Research

Protocol for Intervention Studies

Objective: To develop and evaluate interventions that bridge identified gaps between ethical ideals and clinical reality.

Methodology:

- Research Design: Interventional studies, quality improvement initiatives, or implementation science approaches

- Intervention Development: Co-design with stakeholders based on Stage 2 findings

- Evaluation Framework: Mixed-methods assessment of process and outcome measures

- Analysis Plan: Pre-post comparisons, comparative effectiveness, or process evaluation

Application Example: Designing and testing enhanced consent processes for clinical research participation that address previously identified deficiencies in subject comprehension [6]. This directly addresses the gap between the ideal of informed consent and actual understanding.

Key Outputs:

- Tested interventions for improving ethical practice

- Implementation strategies for ethical ideals

- Evidence for practice change initiatives

Stage 4: Changing Ethical Norms Research

Protocol for Normative-Integrative Studies

Objective: To synthesize empirical findings from multiple studies to inform, refine, or potentially modify ethical norms and principles.

Methodology:

- Research Design: Systematic integration, meta-ethnography, or reflective equilibrium approaches

- Data Synthesis: Aggregation of empirical findings across related studies

- Normative Analysis: Critical evaluation of existing ethical frameworks in light of empirical evidence

- Integration Method: Explicit methodology for moving from empirical findings to normative conclusions

Application Example: Reconsidering autonomy frameworks in chronic illness management based on cumulative empirical findings about patient preferences, decision-making patterns, and relational dynamics in ongoing care [2] [10].

Key Outputs:

- Refined ethical frameworks or principles

- Evidence-informed normative recommendations

- Revised practice guidelines or policies

Integration Methodologies

Stage 4 research requires sophisticated integration of empirical and normative approaches, with several methodological options available:

Table 3: Integration Methodologies for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Methodology | Description | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective Equilibrium | Back-and-forth process between ethical principles and empirical data to achieve coherence [2] | Individual researcher analysis; theoretical refinement | Requires transparency about weighting of different elements |

| Dialogical Empirical Ethics | Structured dialogue between researchers and stakeholders to develop shared understanding [2] | Practice guideline development; policy formation | Demands skilled facilitation and representative participation |

| Ground Moral Analysis | Iterative process of data collection and normative analysis to develop contextually grounded recommendations [2] | Emerging ethical issues; novel technologies | Time-intensive; requires interdisciplinary team |

| Symbiotic Ethics | Integration of empirical and normative elements throughout research process [2] | Complex practice environments; organizational ethics | Challenges traditional research boundaries |

Researchers report that the most contested objectives in empirical bioethics are "striving to draw normative recommendations" and "developing and justifying moral principles," while "understanding the context of a bioethical issue" and "identifying ethical issues in practice" receive nearly unanimous support [10]. This reflects both methodological challenges and disciplinary tensions within the field.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Methodological Resources for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Research Component | Essential Tools & Methods | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Mixed-methods frameworks, Case study protocols, Comparative analysis templates | Enables comprehensive approach to complex questions | Integrating quantitative practice data with qualitative experience data |

| Data Collection | Validated survey instruments, Semi-structured interview guides, Systematic observation protocols | Ensures reliable and valid data collection | Assessing quality of life; exploring decision-making experiences |

| Normative Framework | Ethical principle checklists, Deliberative frameworks, Case analysis templates | Provides structure for ethical analysis | Applying four-principles approach; utilizing casuistry methods |

| Integration Methodology | Reflective equilibrium protocols, Dialogical procedure guides, Interdisciplinary team facilitation methods | Supports systematic empirical-normative integration | Translating patient preference data into practice recommendations |

| Analysis Tools | Qualitative analysis software (NVivo, MAXQDA), Statistical packages (R, SPSS), Ethical analysis frameworks | Facilitates robust data analysis and interpretation | Identifying themes in interview data; testing associations in survey data |

Integrated Research Workflow Protocol

The complete four-stage research process can be implemented through the following comprehensive workflow:

Comprehensive Four-Stage Research Workflow

This integrated protocol provides researchers with a systematic approach to addressing bioethical issues through sequential, cumulative stages of inquiry. Each stage builds upon the previous one, creating a comprehensive evidence base for ethical analysis and decision-making.

For drug development professionals and researchers, this framework offers a structured methodology for investigating ethical dimensions of pharmaceutical research, clinical trials, and therapeutic implementation. By progressing through these stages, research teams can ensure their empirical bioethics work progresses from basic understanding to meaningful impact on ethical practice and policy.

Application Notes: Integrating Empirical Data and Normative Analysis

The Challenge of Integration in Empirical Bioethics

Empirical bioethics constitutes an interdisciplinary endeavor that centers on integrating empirical findings with normative, philosophical analysis [2]. This integration is crucial for addressing the complexity of human practices in healthcare and biological sciences, moving beyond purely philosophical approaches that may lack contextual sensitivity [15] [2]. The fundamental challenge lies in successfully merging social scientific, empirical data with philosophical analysis to generate normatively sound and practically applicable conclusions [15].

Despite consensus that empirical research is relevant to bioethical argument, integrating empirical research with normative analysis remains methodologically challenging [2]. A systematic review has identified at least thirty-two distinct methodologies for integration, reflecting both the richness and uncertainty within the field regarding aims, content, and domain of application [2]. Many researchers report an "air of uncertainty and overall vagueness" surrounding integration methods, which represents a double-edged sword—allowing flexibility while potentially obscuring a lack of methodological understanding [2].

Methodological Approaches to Integration

Table 1: Primary Methodological Approaches for Empirical-Normative Integration

| Method Category | Key Characteristics | Representative Methods | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consultative | Researcher as external thinker analyzing data independently to develop normative conclusions | Reflective Equilibrium, Reflexive Balancing | Issues requiring coherentist moral justification; theoretical analysis of empirical data |

| Dialogical | Reliance on stakeholder dialogue to reach shared understanding of analysis and conclusions | Inter-ethics, Dialogical Empirical Ethics | Clinical ethics support; policy development; stakeholder engagement contexts |

| Inherent Integration | Normative and empirical components intertwined from research project inception | Grounded Moral Analysis, Symbiotic Ethics | Exploratory research; contexts where normative frameworks emerge from empirical data |

Quantitative Data Presentation in Comparative Studies

Effective presentation of quantitative data is essential for empirical bioethics research that incorporates comparative studies. The following table demonstrates proper summarization of quantitative variables across different groups:

Table 2: Exemplary Quantitative Data Summary for Group Comparisons

| Group | Mean | Standard Deviation | Sample Size (n) | Median | Interquartile Range (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 2.22 | 1.270 | 14 | 1.70 | 1.50 |

| Group B | 0.91 | 1.131 | 11 | 0.60 | 0.85 |

| Difference | 1.31 | N/A | N/A | 1.10 | N/A |

When comparing quantitative variables between groups, researchers should calculate differences between means and/or medians, while recognizing that standard deviation and sample size metrics do not apply to these difference measurements [16]. Appropriate visualization methods include back-to-back stemplots for small datasets with two groups, 2-D dot charts for small to moderate amounts of data across multiple groups, and boxplots for larger datasets [16].

Experimental Protocols for Empirical Bioethics Research

Comprehensive Research Protocol Template

A robust protocol template suitable for empirical bioethics investigations must accommodate the epistemological and methodological frameworks specific to humanities and social sciences in the health domain [7] [17]. The following protocol structure has been specifically adapted for empirical bioethics research:

Table 3: Core Protocol Template for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Section | Key Components | Considerations for Empirical Bioethics |

|---|---|---|

| Title & Identification | Nature of study, approach, data collection methods | Clearly identify as empirical bioethics; specify interdisciplinary nature |

| Administrative Information | Sponsors, investigators, research teams | Include ethics committee/IRB details; specify interdisciplinary team composition |

| Study Summary | Context, primary objective, general method | Articulate both empirical and normative dimensions concisely |

| Problem & Objectives | Problem significance, literature, specific research questions | Frame to demonstrate need for empirical-normative integration |

| Disciplinary & Paradigmatic Framework | Disciplinary field, research paradigm, theoretical framework | Explicitly state methodological framework (qualitative/quantitative/mixed) and theoretical framework (e.g., principlism) |

| Methodological Details | Site, duration, participant characteristics, sampling, data collection | Justify participant sampling; specify empirical methods and normative analysis approach |

| Ethical Considerations | Consent procedures, information notices, data protection | Adapt consent approaches (implicit/explicit, oral/written) based on study context; balance autonomy with methodological needs |

Data Collection and Processing Protocols

For data collection in empirical bioethics, researchers should specify the types of data collected, procedures, instruments (interview guides, questionnaires), and equipment used [7]. The protocol should address whether any changes in instruments might occur during the study and whether public members will participate in the process [7].

Data processing, storage, protection, and confidentiality procedures require particular attention in empirical bioethics [17]. Rather than imposing excessive anonymization that might limit analytical depth, responsible pseudonymization is often more appropriate, particularly when working with qualitative data from semi-directed interviews or open-ended questionnaires that may require follow-up data collection [17].

Integration Methodology Protocol

The integration of empirical findings with normative analysis represents the core methodological challenge in empirical bioethics. Researchers must transparently document their approach to integration:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Empirical Bioethics

Table 4: Essential Methodological Resources for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Research 'Reagent' | Function/Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Realism Framework | Philosophical foundation for integrating empirical data with philosophical analysis | Provides mature interdisciplinary approach; addresses fact-value distinction [15] |

| Reflective Equilibrium Methodology | Structured approach for back-and-forth dialogue between ethical principles and empirical data | Enables researcher to achieve moral coherence between normative underpinnings and empirical facts [2] |

| Standardized Protocol Templates | Adapted research protocols for humanities and social sciences in health | Based on SRQR standards but modified for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods [7] [17] |

| Dialogical Integration Methods | Facilitates stakeholder collaboration in normative analysis | Particularly valuable when multiple perspectives essential to ethical analysis [2] |

| Adapted Consent Procedures | Flexible informed consent approaches specific to empirical ethics contexts | Balances methodological needs with ethical requirements; considers implicit/oral consent where appropriate [17] |

| Empirical Data Collection Instruments | Interview guides, questionnaires, observation protocols | Must be designed to minimize bias from prior information while maintaining ethical standards [17] |

Implementation Framework and Best Practices

Professional Standards and Quality Assessment

The development of professional standards in empirical bioethics remains contested, with ongoing debates about what constitutes expertise in this interdisciplinary field [18]. Suggested criteria for quality empirical bioethics research include:

- Understanding and executing appropriate empirical and analytic methods [18]

- Awareness of relevant standards and requirements for bioethics research and related disciplines [18]

- Contextualizing findings in relation to further important ethical questions [18]

Peer review processes serve as a primary mechanism for quality assessment, though limitations exist due to varied reviewer attitudes, diverse publication genres within bioethics, and the absence of an established canon of literature against which standards could be judged [18].

Ethical Considerations in Empirical Bioethics Protocols

Ethical review of empirical bioethics research requires special consideration of several factors that distinguish it from biomedical research. The physical or mental health risks to participants are generally small or nonexistent, at least in the domain of empirical bioethics [17]. This risk profile allows for adaptations to standard ethical requirements:

Information notices that are too exhaustive or oriented may influence participant behavior or responses, potentially increasing study bias and decreasing result pertinence [17]. Written consent may be difficult or inappropriate to obtain systematically, particularly in qualitative approaches such as non-participant observations in hospital settings [17]. Excessive anonymization requirements may limit researchers' ability to deepen certain imperative analyses, particularly with qualitative data from interviews or open-ended questionnaires [17].

These considerations support a case-by-case contextualization approach that does not ignore fundamental research policies, standards, and legislations, but adapts them to the specific methodological requirements of empirical bioethics research [17].

Empirical bioethics is an interdisciplinary field that integrates empirical research findings with normative philosophical analysis to address complex ethical challenges in healthcare and scientific research [2]. This hybrid approach recognizes that a purely theoretical ethical analysis is often insufficient for grappling with the nuanced realities of human practices in medicine and scientific investigation [2]. The growing consensus in the field indicates that empirical evaluations alone cannot ensure that practices in areas such as eHealth and neurotechnology are ethically sound, necessitating the integration of robust ethical frameworks into research design and implementation [19] [20]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing four dominant ethical theories—utilitarianism, deontology, principlism, and virtue ethics—within interdisciplinary empirical bioethics research, with particular emphasis on contexts relevant to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Table 1: Core Ethical Theories in Empirical Bioethics Research

| Ethical Theory | Central Principle | Primary Advocates | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utilitarianism | Maximize overall happiness/utility; greatest good for greatest number | Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill [21] | Provides clear framework for resource allocation; emphasizes measurable outcomes | Can justify sacrificing minority interests; requires difficult utility calculations [21] |

| Deontology | adherence to moral rules and duties; actions inherently right or wrong | Immanuel Kant [22] | Protects individual rights and autonomy; provides consistent moral framework | Can lead to rigid outcomes that ignore consequences; may conflict with pragmatic solutions [22] |

| Principlism | Balance of four core principles: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice | Beauchamp and Childress [23] | Flexible framework for clinical ethics; comprehensive consideration of moral dimensions | Lacks hierarchical structure; principles may conflict without resolution method [23] |

| Virtue Ethics | Cultivation of moral character and virtues in practitioners | Aristotle [23] [24] | Focuses on moral motivation and character; emphasizes practical wisdom | Less specific action guidance; challenges in assessing virtuous qualities [24] |

Theoretical Foundations and Research Applications

Utilitarian Ethics: Consequentialist Framework

Utilitarianism is a consequentialist ethical theory that posits the morality of actions should be judged solely by their consequences, with the goal of achieving the greatest balance of good over bad consequences for the greatest number of people [21]. In its modern applications, utilitarianism provides a vibrant moral resource for contemporary bioethics, particularly in contexts requiring resource allocation and public health policy decisions [21]. Unlike deontological approaches, utilitarian ethics judges acts exclusively on the basis of their outcomes, seeking to maximize either happiness, pleasure, or other specified utilities depending on the particular variant endorsed [21].

Within research environments, utilitarianism provides a structured approach for evaluating the potential benefits and harms of studies involving human participants, particularly when dealing with scarce resources or when research might impose burdens on some individuals while generating knowledge that benefits many others [21]. However, critics have highlighted significant limitations, including the theory's potential to justify the sacrifice of minority interests for the greater good and the challenge of making accurate utility calculations in morally pluralistic societies where definitions of "good" consequences may vary substantially [21]. The theory has also been criticized for creating emotional distance between researchers and participants by reducing ethical decisions to mathematical calculations [21].

Deontological Ethics: Duty-Based Framework

Deontology, derived from the Greek "deont" meaning "that which is binding," is an ethical approach centered on rules and professional duties, most famously associated with the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) [22]. Kantian deontology stems from the belief that humans possess the ability to reason and understand universal moral laws applicable across situations [22]. Unlike consequentialist approaches, deontology does not focus on the outcomes of individual actions but rather on the intent behind chosen actions and their adherence to moral principles [22].

Kant divided deontological beliefs between hypothetical and categorical imperatives, with the latter representing unconditional moral absolutes [22]. One of Kant's most famous categorical imperatives requires that individuals never treat people solely as a means to an end, emphasizing respect for each individual's unique worth and dignity [22]. In healthcare contexts, Kantian deontology would strongly emphasize truth-telling, full disclosure of medical errors, and respect for patient autonomy, regardless of potential negative consequences that might result from these actions [22]. This stands in direct contrast to utilitarian approaches that might justify withholding information if it produced better overall outcomes [22].

Principlism: Bridging Theory and Practice

Principlism represents a pluralistic approach to bioethics that balances multiple mid-level principles rather than deriving moral guidance from a single overarching theoretical foundation [23]. This framework dominates contemporary clinical ethics and medical education, offering a structured yet flexible approach to ethical decision-making [23] [24]. The framework incorporates four core principles: respect for autonomy (honoring an individual's right to make informed decisions about their own healthcare), beneficence (the obligation to act in the patient's best interest and promote well-being), non-maleficence (the commitment to "do no harm" and avoid causing unnecessary injury or suffering), and justice (ensuring fairness in the distribution of healthcare resources and treatments) [23].

In research contexts, principlism provides a comprehensive checklist of ethical considerations that must be balanced when designing and implementing studies [23]. For example, in eHealth evaluation research, principlism helps researchers navigate tensions between promoting innovative care (beneficence) and ensuring equitable access to technology (justice) [19]. The approach is particularly valuable in interdisciplinary empirical bioethics because it offers a shared vocabulary and structured framework that team members from different backgrounds can apply to complex ethical dilemmas without requiring deep philosophical expertise [23].

Virtue Ethics: Character-Based Framework

Virtue ethics represents a character-based approach to morality that centers on the moral agent rather than specific actions or their consequences [23]. Originating from Aristotelian philosophy, this perspective emphasizes the cultivation of virtuous character traits such as compassion, honesty, and practical wisdom [23] [24]. In bioethical contexts, virtue ethics encourages healthcare professionals and researchers to develop these moral virtues as guides for ethical behavior in practice [23].

Recent applications in neuroethics research have argued for integrating virtue ethics to address ethical challenges in cutting-edge brain research, emphasizing the development of "moral sensitivities, practical reasoning skills, and other ethical competencies" rather than relying solely on regulations and rules [20]. This approach is particularly valuable for navigating complex conflicts of interest and promoting collaborative ethical deliberation among researchers, ethicists, and participants [20]. In medical ethics education, virtue ethics is increasingly incorporated through a hybrid approach that combines principlist methodologies with virtue cultivation, using tools such as exemplars and case-based learning to foster both moral knowledge and character development [24].

Table 2: Research Applications of Ethical Frameworks in Empirical Bioethics

| Research Context | Utilitarian Approach | Deontological Approach | Principlist Approach | Virtue Ethics Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eHealth Evaluation | Focus on maximizing population health benefits through technology implementation [19] | Emphasis on truth-telling and full disclosure of technology limitations [22] | Balancing patient autonomy, beneficence, and justice in technology access [19] | Cultivating honesty and integrity in reporting both positive and negative outcomes [20] |

| Invasive Neurotechnology Research | Weighing potential knowledge benefits against risks to participants [20] | Strict adherence to informed consent protocols and never using participants merely as means [22] [20] | Ensuring equitable participant selection (justice) while minimizing harm (non-maleficence) [23] | Developing researchers' moral character to navigate complex conflicts of interest [20] |

| Pharmaceutical Drug Development | Prioritizing research on diseases affecting largest populations [21] | Absolute duty to disclose all trial results, including unfavorable findings [22] | Balancing access to experimental drugs (autonomy) with safety protections (non-maleficence) [23] | Fostering compassion and scientific integrity throughout development process [24] |

| Rare Disease Therapy Development | Allocating resources to interventions with greatest overall health utility [21] | Duty to provide research opportunities for all patient groups regardless of size [22] | Special consideration of justice implications for orphan drug development [23] | Cultivating perseverance and commitment to underserved patient populations [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Ethical Integration

Protocol 1: Reflective Equilibrium for Empirical Bioethics Integration

The reflective equilibrium method represents a systematic approach to integrating empirical findings with normative analysis through iterative deliberation [2]. This protocol adapts the methodology for interdisciplinary research teams in empirical bioethics.

Objective: To achieve coherence between empirical data, ethical principles, and considered moral judgments through a structured reflective process.

Materials Required:

- Empirical research data (qualitative or quantitative)

- Documentation of initial ethical positions

- Framework of relevant ethical principles/theories

- Recording device or notebook for process documentation

Procedure:

- Initial Position Mapping: Research team members individually document their initial ethical judgments about the research dilemma based on intuition and preliminary understanding.

- Principle Formulation: Identify relevant ethical principles and theories applicable to the dilemma, with explicit justification for their selection.

- Data Integration: Systematically compare empirical findings with identified principles, noting areas of alignment and tension.

- Iterative Adjustment: Engage in reflective deliberation to adjust either principles or judgments to achieve greater coherence.

- Equilibrium Achievement: Document the point at which researchers reach a stable equilibrium between principles, judgments, and empirical data.

- Resolution Documentation: Create a comprehensive record of the reflective process, including all adjustments and final normative conclusions.

Validation Method: Peer review by interdisciplinary ethics advisory board to assess coherence and justification of the resulting ethical position.

Expected Timeline: 4-6 weeks for complete process, depending on complexity of ethical dilemma.

Protocol 2: Dialogical Empirical Ethics for Stakeholder Engagement

Dialogical empirical ethics emphasizes collaborative sense-making through structured dialogue between researchers and stakeholders [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing ethical aspects in emerging technologies like eHealth and neurotechnology.

Objective: To co-construct ethical guidance through deliberative dialogue that incorporates diverse stakeholder perspectives.

Materials Required:

- Trained facilitator with ethics expertise

- Diverse stakeholder participants (researchers, patients, clinicians, community representatives)

- Recording and transcription equipment

- Ethical framework guide

- Anonymous voting technology

Procedure:

- Stakeholder Mapping: Identify and recruit relevant stakeholders representing all affected parties.

- Pre-Dialogue Assessment: Administer survey to assess initial ethical positions and concerns.

- Structured Dialogue Sessions:

- Session 1: Case presentation and initial reactions

- Session 2: Ethical principle identification and application

- Session 3: Deliberation on points of disagreement

- Session 4: Consensus-building on ethical recommendations

- Data Analysis: Thematic analysis of dialogue transcripts to identify key ethical considerations.

- Recommendation Formulation: Co-create ethically justified recommendations for practice.

- Implementation Planning: Develop strategy for integrating ethical recommendations into research practice.

Validation Method: Member checking with participants to ensure accurate representation of dialogue and consensus.

Expected Timeline: 8-10 weeks for complete dialogue process and analysis.

Integration Workflow Visualization

Empirical Bioethics Integration Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Ethical Analysis Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Empirical Bioethics Research

| Tool Category | Specific Method/Instrument | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Instruments | Semi-structured interview guides | Gather rich qualitative data on stakeholder moral experiences | Understanding researcher perspectives on ethical challenges in neurotechnology [20] |

| Ethical Analysis Frameworks | Principlism checklist | Systematic application of four core principles to ethical dilemmas | Clinical ethics consultation and research ethics review [23] |

| Integration Methodologies | Wide reflective equilibrium | Achieve coherence between empirical data and ethical principles | Bridging empirical findings and normative analysis in bioethics research [2] |

| Deliberative Processes | Structured stakeholder dialogues | Facilitate collaborative ethical sense-making among diverse stakeholders | Addressing ethical aspects in eHealth evaluation research [19] [2] |

| Educational Resources | AI-assisted virtue cultivation tools | Develop moral sensitivity and practical wisdom through exemplars | Medical ethics education for students and researchers [24] |

| Validation Instruments | Interdisciplinary peer review | Ensure robustness and justification of ethical conclusions | Quality assessment in empirical bioethics research publications [2] |

Implementation Guidelines and Case Applications

Case Application: Ethical Integration in eHealth Evaluation Research

The protocol for examining ethical aspects in eHealth evaluation research demonstrates the practical integration of ethical frameworks into empirical research design [19]. This scoping review protocol systematically investigates how ethical considerations are addressed in original studies evaluating remote patient monitoring (RPM) applications for cancer and cardiovascular diseases [19]. The protocol employs Joanna Briggs Institute methodology and PRISMA-ScR guidelines, implementing a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases including MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and Philosopher's Index [19].

The ethical analysis within this protocol focuses on two key domains: process domain ethical aspects (concerned with power distribution and value judgments in the research process) and outcome domain ethical aspects (addressing unintended consequences and dual uses of eHealth technologies) [19]. The protocol specifically examines how evaluation studies address issues such as health disparities, data security, and selection bias, with analysis applying inductive-deductive qualitative content analysis to map ethical considerations [19]. This approach enables the identification of opportunities for more holistic integration of ethics into eHealth evaluation practices and informs future practical guidance for researchers [19].

Implementation Framework for Neuroethics Research

Recent qualitative research with NIH BRAIN Initiative-funded investigators reveals the complex ethical challenges in invasive brain research with humans [20]. The study identifies two major themes: (1) the difficulty of navigating complex conflicts of interest arising from research funding, team structure, data collection and sharing obligations, commercialization, innovation, and the boundaries between research and care; and (2) the need for increased collaboration, community, and participation in neuroethics deliberation [20].

Based on these findings, researchers argue for a shift from focusing solely on ethical guidelines to promoting neuroethical competencies through virtue ethics integration [20]. The proposed implementation framework includes:

- Targeted neuroethics education that develops moral sensitivities and practical reasoning skills

- Opportunities for collective moral deliberation among researchers, ethicists, and participants

- Enhanced engagement practices that recognize researchers as unique stakeholders with significant agency and experiential knowledge [20]

This approach addresses limitations of principle-based and regulatory approaches alone by cultivating the moral character and virtues necessary to navigate ethical issues that emerge throughout the research lifecycle [20].

Protocol 3: Virtue Ethics Integration for Researcher Competency Development

This protocol outlines a structured approach to integrating virtue ethics into research team development, based on findings from neuroethics research demonstrating the value of moral competencies for navigating ethical challenges [20].

Objective: To cultivate neuroethical competencies among research team members through virtue ethics education and collective moral deliberation.

Materials Required:

- Case studies representing ethical challenges in specific research domain

- Exemplar narratives of ethical leadership in science

- Facilitated discussion guides

- Reflective journal templates

- Assessment rubrics for ethical competencies

Procedure:

- Pre-assessment: Evaluate team members' current ethical competencies and identified challenges.

- Exemplar Identification: Select and analyze exemplars of virtuous practice in relevant research contexts.

- Case-Based Deliberation: Engage team in structured analysis of ethical dilemmas using virtue framework.

- Moral Reflection: Implement regular reflective practice sessions for research team.

- Competency Development: Focus on cultivating specific virtues identified as essential for research context.

- Integration Planning: Develop strategies for applying virtuous practice to current research projects.

- Ongoing Support: Establish structures for continued ethical development and consultation.

Assessment Metrics:

- Pre/post self-assessment of ethical confidence

- Peer evaluation of collaborative ethical decision-making

- Documentation of ethical issues identified and addressed

- Reflection journal quality and depth

Implementation Timeline: 12-week intensive program with quarterly follow-up sessions.

The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) with persistent global health disparities represents a critical frontier for empirical bioethics. This field, characterized by its integration of normative ethical analysis with empirical evidence, provides the essential framework for navigating the complex societal, technical, and ethical challenges of this era [26] [27]. The "empirical turn" in bioethics emphasizes that ethical deliberation must be grounded in the realities of how technologies are developed and how they impact diverse populations [27]. AI's rapid adoption in healthcare underscores an urgent need for this approach. While 88% of organizations report using AI in some business function, most remain in early experimental phases, and a significant 95% of generative AI pilot programs fail to deliver measurable revenue impact [28] [29]. Simultaneously, global health progress is faltering; global life expectancy fell by 1.8 years between 2019 and 2021, reversing a decade of gains and highlighting the vulnerability of health systems [30]. This article applies the lens of empirical bioethics to analyze these parallel challenges, proposing structured application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in fostering equitable and ethically sound innovation.

Application Note 1: AI Adoption and Value Realization

Quantitative Landscape of AI Implementation

The current state of AI adoption is a paradox of widespread experimentation and scarce enterprise-wide value. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from recent global surveys.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Indicators of AI Adoption and Impact in 2025

| Indicator | Metric | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Overall AI Adoption | 88% of organizations report regular use in at least one business function [28]. | McKinsey Global Survey |

| Generative AI Pilot Success | Only 5% of generative AI pilot programs achieve rapid revenue acceleration [29]. | MIT NANDA Initiative |

| AI Agent Experimentation | 62% of organizations are at least experimenting with AI agents [28]. | McKinsey Global Survey |

| Enterprise-Level EBIT Impact | 39% of respondents attribute any level of EBIT impact to AI use [28]. | McKinsey Global Survey |

| Leading Driver for AI High Performers | 80% of companies set efficiency as an AI objective, but high performers prioritize growth and innovation [28]. | McKinsey Global Survey |

Protocol for Interdisciplinary AI Impact Assessment

This protocol is designed to evaluate the real-world impact and ethical implications of AI deployments in healthcare and research settings, aligning with empirical bioethics methodologies [26].

Protocol 1.1: Mixed-Methods AI Impact and Ethics Assessment

- Objective: To quantitatively measure AI implementation outcomes and qualitatively understand the associated ethical challenges and workforce perceptions.

- Materials:

- Data Integration Platform: Secure computing environment for aggregating pre- and post-AI implementation performance metrics (e.g., process efficiency, diagnostic accuracy).

- Structured Interview Guides: Semi-guided questionnaires for leadership, focusing on strategic objectives and perceived value [28] [29].

- Focus Group Frameworks: Discussion guides for line managers and end-users to explore workflow changes, trust, and accountability.

- Bias Audit Toolkit: Software for running statistical analyses on AI model outputs across different demographic subgroups [31] [32].

- Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement: Establish key performance indicators (KPIs) prior to AI integration. Examples include time-to-completion for target tasks, error rates, and resource costs.

- Post-Implementation Measurement: Collect the same KPI data after a minimum of two full operational cycles with the AI tool.

- Stakeholder Engagement:

- Conduct individual interviews with senior leaders to understand strategic drivers.

- Facilitate focus groups with operational staff to gather lived experiences of AI integration.

- Ethical Scrutiny and Bias Audit: Apply the bias audit toolkit to the AI system using a hold-out dataset or simulated cases to test for discriminatory performance patterns.

- Data Triangulation: Integrate quantitative performance data with qualitative thematic analysis from interviews and focus groups. The normative ethical analysis, central to bioethics, is applied here to evaluate findings against principles of justice, fairness, and accountability.

- Output: A comprehensive report detailing quantitative ROI, qualitative insights into organizational disruption, and an ethical impact assessment with recommendations for mitigation.

Visualizing the AI Integration Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for a responsible AI implementation and assessment, a process that should be iterative and guided by ethical principles.

Application Note 2: AI and Global Health Equity

Quantitative Landscape of Health Disparities and AI Exclusion

The promise of AI in healthcare is starkly contrasted by the reality of global health disparities and the risk of technological exclusion. The data reveals a pressing challenge.

Table 2: Health Disparities and AI Exclusion Risks in 2025

| Category | Metric | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Global Health Setbacks | Global life expectancy fell by 1.8 years between 2019-2021 [30]. | World Health Statistics |

| Maternal Health in Crises | 60% of preventable maternal deaths occur in displacement settings [33]. | Project HOPE |

| AI Diagnostic Bias | Algorithmic bias can lead to 17% lower diagnostic accuracy for minority patients [32]. | ScienceDirect Review |

| Genomic Data Gap | >80% of genetics studies include people of European descent (<20% of global population) [31]. | Deutsche Welle / WEF |

| Digital Divide | 29% of rural adults are excluded from AI-enhanced healthcare tools [32]. | ScienceDirect Review |

| Scale of Exclusion | AI in healthcare risks excluding nearly 5 billion people in low and middle-income countries [31]. | World Economic Forum |

Protocol for Equity-Centric AI Development and Validation

This protocol provides a methodology for developing and validating AI health tools with equity as a core objective, directly addressing the data biases and exclusion risks identified above.

Protocol 2.1: Co-Design and Equity Validation for AI Health Tools

- Objective: To create and validate AI-powered health tools that are effective across diverse genetic, environmental, and demographic populations.

- Materials:

- Diverse Data Repositories: Curated datasets from multiple global regions, ensuring representation of different genetic backgrounds, skin tones, and disease presentations [31] [32].

- Community Engagement Panel: A structured group of stakeholders, including community health workers, patient advocates, and local ethicists from target populations.

- Model Validation Suite: A standardized set of test cases covering a wide spectrum of demographic and clinical scenarios.

- Digital Literacy Materials: Culturally and linguistically appropriate resources to facilitate informed consent and tool usage.

- Procedure:

- Problem Scoping with Communities: Convene the community engagement panel at the outset to define the health priority and design parameters, ensuring the tool addresses a locally relevant need.

- Federated Learning & Data Sourcing: Procure diverse training data. Where data sovereignty is a concern, employ federated learning techniques that train algorithms across multiple decentralized data sources without transferring the data itself.

- Iterative Co-Design Prototyping: Develop initial prototypes and present them to the community panel for feedback on usability, cultural appropriateness, and integration into local workflows.

- Rigorous Equity-Centered Validation: Test the final model using the validation suite. Performance metrics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity) must be disaggregated and reported by subgroup (e.g., ethnicity, gender, geographic location) to identify any performance gaps.

- Implementation with Support: Deploy the tool alongside the necessary digital literacy training for both providers and patients, and with a plan for ongoing monitoring and maintenance.

- Output: An AI health tool documented with performance metrics across diverse subgroups, a report on the co-design process, and implementation guidelines for low-resource settings.

Visualizing the Equity-Centric AI Development Pathway

An equity-first approach requires a fundamental shift in the development lifecycle, as illustrated in the following pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers embarking on the empirical bioethics studies and technical developments outlined in these protocols, the following toolkit details essential "research reagents" – the conceptual frameworks and practical resources required.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Interdisciplinary Bioethics Research

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Empirical Bioethics Methodology [26] [27] | The core framework for integrating descriptive empirical research (e.g., surveys, interviews) with normative ethical analysis. It provides the philosophical grounding for the entire research process. |

| Stakeholder Engagement Panel | A pre-recruited and structured group of community representatives, patients, and end-users. Its function is to provide grounded, lived-experience input throughout the technology development lifecycle, from scoping to validation (Protocol 2.1). |

| Bias Audit Toolkit [31] [32] | A suite of software and statistical measures (e.g., fairness metrics, disparate impact analysis) used to proactively identify and quantify algorithmic bias in AI models against protected or underrepresented subgroups. |

| Mixed-Methods Data Collection Instruments | Validated questionnaires, structured interview guides, and focus group protocols. Their function is to systematically gather both quantitative performance data and qualitative perceptual data for triangulation (Protocol 1.1). |

| Federated Learning Infrastructure | A distributed machine learning approach that allows for model training on data that remains in its original location. Its function is to enable the use of diverse datasets while respecting data privacy and sovereignty regulations [31]. |

Synthesis and Forward-Looking Perspective

The interplay between the sluggish, often unsuccessful adoption of AI and the persistent crisis of global health disparities reveals a common root: a lack of deep, integrative, and ethically attuned implementation. The quantitative data shows that high-performing organizations succeed by embedding AI into redesigned workflows and pursuing growth and innovation, not just efficiency [28]. Similarly, overcoming health equity challenges requires more than just advanced algorithms; it demands intentional co-design, investment in local digital infrastructure, and the creation of fair governance frameworks [31] [32]. The empirical bioethics approach is not merely an academic exercise; it is a practical necessity. It provides the methodological rigor to move from simply identifying these complex problems to developing and testing actionable, evidence-based solutions. For researchers and drug development professionals, the path forward lies in embracing this interdisciplinary ethos, ensuring that the powerful drivers of AI and biomedical innovation are steered by a commitment to justice, equity, and tangible human benefit.

The Integrative Toolkit: Methodologies for Combining Empirical Research and Ethical Analysis

Empirical bioethics is an interdisciplinary endeavor that seeks to integrate empirical data with normative analysis to address bioethical questions [34]. Within this field, consultative models represent a distinct methodological approach where the researcher acts as an external thinker who analyzes empirical data and ethical theory independently to develop normative conclusions [2]. This contrasts with dialogical models that rely on direct stakeholder dialogue to reach shared understanding [2]. The consultative approach is particularly valuable when research requires specialized ethical expertise or when dealing with sensitive topics where direct stakeholder engagement may be impractical or ethically problematic.

The systematic review by Davies et al. identified 32 distinct empirical bioethics methodologies, with consultative models representing a significant proportion of these approaches [34]. These methodologies share a common characteristic: the researcher maintains responsibility for the integrative process, systematically moving between empirical findings and normative frameworks to arrive at justified ethical conclusions. This paper provides application notes and protocols for implementing one prominent consultative methodology—Reflective Equilibrium—within interdisciplinary empirical bioethics research, with particular attention to contexts relevant to drug development professionals and clinical researchers.

Theoretical Foundations of Reflective Equilibrium

Conceptual Framework

Reflective Equilibrium (RE), particularly in its "wide" form, is a method of moral justification that seeks coherence among different types of moral considerations [35]. Originally developed by John Rawls and later adapted for bioethics, RE involves a deliberative process where researchers move back-and-forth between ethical principles or theories and concrete moral judgements or empirical data until a state of equilibrium is reached [2]. This process acknowledges that both initial moral intuitions and ethical principles are subject to revision in pursuit of a coherent moral perspective.

The method is fundamentally consultative because the researcher conducts this deliberative process internally, consulting various sources of moral insight but ultimately taking responsibility for the normative conclusions [2]. In empirical bioethics, RE has been tailored to serve research projects by providing a structured approach to integrate empirical findings with ethical analysis [2]. The process does not simply apply pre-existing ethical theories to empirical data but allows for mutual adjustment between theory and data, recognizing that ethical understanding emerges through this iterative process.

Variants and Adaptations

Several adaptations of RE have been developed specifically for empirical bioethics contexts. Wide Reflective Equilibrium expands the elements considered beyond principles and judgements to include ethical theories, background philosophies, and empirical data [35]. Collective Reflective Equilibrium extends the process to incorporate multiple perspectives, making it particularly valuable for policy development where diverse stakeholder views must be considered [36] [37]. This variant is especially relevant for drug development professionals addressing ethical questions that span multiple constituencies including patients, clinicians, researchers, and regulators.

Another significant adaptation is Reflexive Balancing, which emphasizes the critical examination of one's own presuppositions throughout the research process [35]. This approach acknowledges that researchers bring their own moral frameworks and biases to the analytical process and encourages explicit engagement with these factors. For researchers in pharmaceutical contexts, this reflexivity is crucial when addressing ethically complex areas such as clinical trial design, access to experimental medicines, or ethical allocation of scarce resources.

Implementation Protocol: Applying Reflective Equilibrium

Phase 1: Research Preparation and Scoping

Objective: Establish the foundational elements for the RE process and define the ethical question to be addressed.

Procedure:

- Define the Normative Question: Precisely formulate the ethical question or dilemma to be addressed. In drug development contexts, this might involve questions about inclusion criteria for clinical trials, ethical approaches to risk-benefit assessment, or fair allocation of research resources.

- Identify Preliminary Moral Intuitions: Document initial moral judgements about the question. These may include:

- Researcher's own intuitions

- Common moral positions identified in preliminary literature review

- Institutional or professional guidelines

- Regulatory frameworks

- Select Relevant Ethical Theories: Identify ethical frameworks potentially relevant to the question (e.g., utilitarianism, deontology, principlism, virtue ethics, capabilities approach).

- Design Empirical Component: Develop methodology for gathering empirical data that will inform the ethical analysis. This may involve:

- Qualitative interviews with stakeholders

- Survey of professional attitudes

- Analysis of existing practices through document review