Beyond the Bench: How the Belmont Report's Ethical Framework Validates Modern Gene Therapy Trials

This article explores the critical and ongoing validation of the Belmont Report's ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—within the complex landscape of contemporary gene and cell therapy trials.

Beyond the Bench: How the Belmont Report's Ethical Framework Validates Modern Gene Therapy Trials

Abstract

This article explores the critical and ongoing validation of the Belmont Report's ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—within the complex landscape of contemporary gene and cell therapy trials. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it connects foundational bioethics to current regulatory trends, including the FDA's 2025 guidance on innovative trial designs for small populations. By examining methodological applications, troubleshooting common ethical challenges, and assessing the report's direct influence on policy, this analysis provides a comprehensive framework for integrating these timeless ethical standards into cutting-edge clinical development, ensuring that scientific advancement proceeds with unwavering patient protection.

The Bedrock of Bioethics: Tracing the Belmont Report from Past Principles to Present-Day Relevance

The Ethical Foundations: Nuremberg, Tuskegee, and the Path to the National Commission

The evolution of ethical standards for human subjects research represents a direct response to historical moral failures. The Nuremberg Code (1947) emerged from the post-World War II Doctors' Trial, establishing the foundational principle that "the voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential" [1] [2] [3]. This standard was created specifically to prevent a recurrence of the atrocities committed by Nazi physicians who conducted horrific experiments on concentration camp inmates without their consent [2] [3]. The Code's first principle emphasizes that participants must have sufficient knowledge and comprehension to make an "understanding and enlightened decision" free from force, fraud, or coercion [1] [3].

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1972) represented a profound domestic ethical failure within the United States. Conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service, this study enrolled 600 African American men under the guise of treating "bad blood" while actually observing the natural progression of untreated syphilis [4]. Researchers actively prevented participants from receiving penicillin even after it became the standard treatment for syphilis in 1947, leading to unnecessary deaths and complications [2] [4]. The study continued until 1972 when a whistleblower exposed it, generating public outrage and prompting Congressional action [3] [4].

These historical events directly led to the National Research Act of 1974, which created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [5] [3]. This Commission was charged with identifying comprehensive ethical principles for human subjects research, resulting in the 1979 Belmont Report [5] [3]. The Belmont Report established three fundamental principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—that continue to govern human subjects research in the United States [5] [3].

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Events in Research Ethics

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Nuremberg Code | Established voluntary consent as absolutely essential after Nazi experiments [2] [3] |

| 1932-1972 | Tuskegee Syphilis Study | U.S. Public Health Service withheld treatment from African American men with syphilis [2] [4] |

| 1964 | Declaration of Helsinki | World Medical Association recommendations distinguishing therapeutic/non-therapeutic research [5] [2] |

| 1974 | National Research Act | Created National Commission after Tuskegee scandal exposed [5] [3] |

| 1979 | Belmont Report | Published ethical principles of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice [5] [3] |

Validation of Belmont Report Principles in Contemporary Gene Therapy Research

Application of Ethical Principles in Modern Trials

The ethical framework established by the Belmont Report demonstrates ongoing relevance and validation through its application to complex challenges in gene therapy clinical trials. The principle of Respect for Persons is operationalized through informed consent processes that have evolved to address the unique characteristics of gene therapies, including their one-time administration and potential long-term risks [6]. Current guidelines emphasize ensuring participant comprehension through methods like "Teach-Back" techniques, where participants explain study information in their own words, confirming their understanding of complex concepts such as vector biology and long-term follow-up requirements [6].

The principle of Beneficence requires careful assessment of risks and benefits, which is particularly challenging in gene therapy given the potential for transformative benefit alongside serious, sometimes fatal, risks [7]. The 2025 safety events surrounding Elevidys (a gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy) exemplify this ongoing balancing act, where reports of patient deaths from acute liver failure led the FDA to temporarily halt the trial and implement additional safeguards, including a Black Box Warning for liver injury [7]. This case demonstrates the continued need for careful risk-benefit assessment aligned with the beneficence principle.

The Justice principle addresses fair subject selection, which is being tested by emerging regulatory pathways for ultra-rare diseases. The FDA's recently developed "N-of-1" pathway addresses justice concerns by creating mechanisms for customized gene therapies for single patients with extremely rare genetic conditions, as evidenced by the approval of a custom CRISPR therapy for an infant with CPS1 deficiency [7]. This approach helps ensure that patients with ultra-rare diseases have access to potentially lifesaving treatments.

Quantitative Evidence from Recent Gene Therapy Trials

Recent clinical trial data provides compelling evidence of how Belmont principles are applied while advancing innovative treatments. The table below summarizes key findings from recent gene therapy trials across different disease areas, demonstrating both efficacy outcomes and safety considerations that reflect ethical implementation.

Table 2: Recent Gene Therapy Clinical Trial Outcomes (2025 Data)

| Therapy | Condition | Trial Phase | Key Efficacy Outcomes | Safety and Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMT-130 [8] | Huntington Disease | Phase 1/2 | 75% slowing of disease progression at 36 months (p=0.003) | Long-term follow-up ongoing for AAV vector-based therapy |

| RGX-121 [8] | MPS II (Hunter syndrome) | Phase 1/2/3 | 82% median reduction in disease biomarker at 1 year; neurodevelopmental stability | Pursuing accelerated approval with biomarker surrogate endpoints |

| DTX401 [8] | Glycogen Storage Disease Type Ia | Phase 3 | 61% reduction in daily cornstarch intake at 96 weeks; improved hypoglycemia control | Ongoing monitoring of metabolic parameters and immune responses |

| CER T-Cell Therapy [8] | Ovarian Cancer | Phase 1 | One patient alive at 28+ months exceeding median survival benchmarks | Dose escalation ongoing (30-fold increase) with no limiting toxicities reported |

| Del-Zota [8] | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | Phase 1/2 | Functional improvements on PUL2 test versus decline in natural history | Includes both ambulatory and non-ambulatory patients in trial population |

Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Therapy Development

The development and ethical implementation of gene therapies requires specialized reagents and materials that ensure both scientific rigor and patient safety. The following toolkit outlines essential components for gene therapy research and their functions in the context of ethical research conduct.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Gene Therapy Trials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Gene Therapy Research | Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| AAV Vectors [9] | Viral delivery system for therapeutic genes; most common vector platform | Extensive characterization required to minimize immune responses and off-target effects [7] |

| Lentiviral Vectors [9] | Viral vector for ex vivo gene modification (e.g., CAR-T therapies) | Integration site analysis needed to assess mutagenesis risk; strict manufacturing controls |

| CRISPR Components [7] | Gene editing machinery for precise genetic modifications | Specificity verification essential to prevent off-target edits; ethical review of heritable changes |

| Biomarker Assays [8] | Quantify target engagement and treatment response (e.g., HS D2S6 for MPS II) | Validation as surrogate endpoints can accelerate approval while ensuring benefit [8] |

| Long-Term Follow-up Protocols [6] | Structured monitoring for delayed adverse events years after administration | Balance between safety data collection and participant burden through patient-centered design |

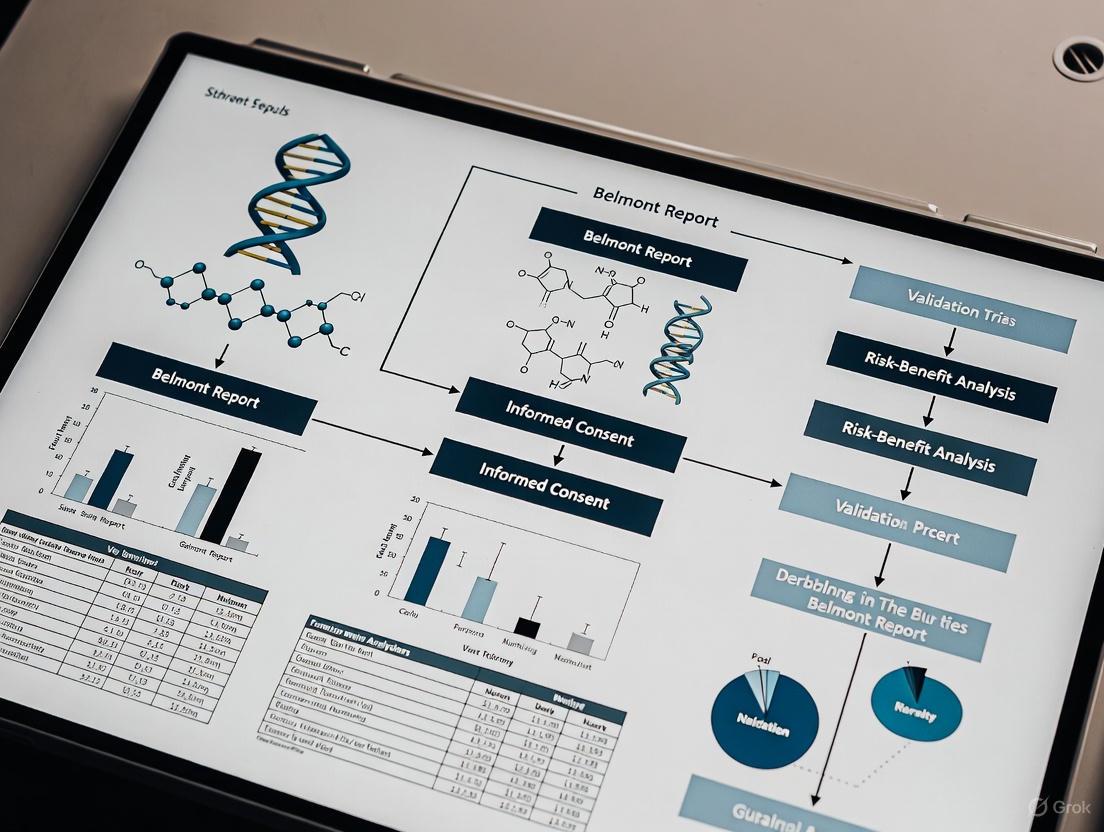

Logical Workflow: From Historical Abuses to Modern Protections

The diagram below illustrates the causal relationship between historical ethical failures and the systematic protections implemented in contemporary gene therapy research, demonstrating how past abuses directly informed current ethical frameworks.

The Belmont Report, formally titled "Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research," was created in 1979 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [5] [3]. This foundational document emerged in response to ethical abuses in research, most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where researchers deliberately denied treatment to African American men with syphilis and prevented them from accessing known cures [3] [10]. The National Commission was established under the National Research Act of 1974, charged with identifying basic ethical principles to guide human subjects research [10].

The Report established three core ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—which form the ethical foundation for modern research regulations in the United States, including the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (the "Common Rule") [11] [12]. These principles were designed to ensure that research values the rights and welfare of individuals, especially in pioneering fields where ethical boundaries are tested.

This analysis examines the validation and application of these three pillars within gene therapy clinical trials, where novel therapeutic interventions present unique ethical challenges. The transition of gene therapies from preclinical research to first-in-human trials represents one of the most ethically significant moments in medical research, making the Belmont framework particularly crucial for this field [5] [13].

The Historical Context and Creation of the Belmont Report

The ethical foundation of the Belmont Report did not emerge in isolation but was shaped by historical events that revealed profound ethical failures in human subjects research.

Key Historical Influences

Table: Historical Events Influencing the Belmont Report

| Event | Time Period | Ethical Failure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuremberg Code | 1947 | Non-consensual, harmful experiments on concentration camp prisoners | Established that "voluntary consent is absolutely essential" for research [3] [10] |

| Thalidomide Disaster | Late 1950s-1962 | Drug testing without adequate safety disclosure or consent | Led to Kefauver Amendments requiring drug efficacy and safety proof [10] |

| Tuskegee Syphilis Study | 1932-1972 | Denied treatment and information to African American men with syphilis | Prompted National Research Act of 1974 and commission creating Belmont Report [3] [10] |

| Willowbrook Hepatitis Studies | 1960s | Deliberate infection of children with disabilities with hepatitis | Raised concerns about vulnerable population exploitation [10] |

| Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study | 1963 | Injection of live cancer cells into elderly patients without consent | Highlighted informed consent deficiencies [10] |

The National Commission that drafted the Belmont Report included theologians, physicians, philosophers, and lawyers who brought diverse perspectives to the challenge of research ethics [5]. The Commission's deliberations recognized that previous ethical codes like the Nuremberg Code and Declaration of Helsinki had significant limitations, particularly regarding protection of vulnerable populations and application beyond traditional medical research [5].

The Report was named after the Belmont Conference Center where the Commission met to draft the document [14]. When published in the Federal Register in 1979, it represented a consensus framework that would influence all federally funded research in the United States [5] [11].

Analytical Framework: The Three Ethical Pillars

The Belmont Report's three ethical principles provide a systematic framework for analyzing research ethics. Each principle carries distinct moral requirements and practical applications.

Respect for Persons

The principle of Respect for Persons incorporates two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [15] [14]. This principle acknowledges the personal dignity and self-determination of individuals, requiring that subjects enter research voluntarily and with adequate information.

In practice, this principle divides into two moral requirements: the requirement to acknowledge autonomy and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy [14]. The application of Respect for Persons occurs primarily through the process of informed consent, which must contain three critical elements: information, comprehension, and voluntariness [15] [10].

For research involving vulnerable populations with diminished autonomy (such as children, prisoners, or individuals with cognitive impairments), additional safeguards are required [14] [12]. The extent of protection is proportionate to the risk of harm and likelihood of benefit, with judgments about autonomy being periodically reevaluated [14].

Beneficence

The principle of Beneficence extends beyond merely avoiding harm to encompass an affirmative obligation to secure participants' well-being [15] [14]. This principle is expressed through two complementary rules: first, "do not harm" and second, maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [15] [10].

Beneficence requires a systematic assessment of risks and benefits [15]. Investigators must thoroughly assess the nature and scope of risks and benefits, considering both individual and societal implications [14]. This assessment serves multiple functions: for investigators, it ensures proper research design; for review committees, it determines whether risks are justified; and for prospective subjects, it informs their participation decision [15].

The principle recognizes that research involving human subjects may not directly benefit participants but must yield "fruitful results for the good of society" that cannot be obtained by other means [3].

Justice

The principle of Justice addresses the fair distribution of research burdens and benefits [15] [16]. This principle requires that the selection of research subjects be scrutinized to ensure that classes of subjects are not selected simply because of their easy availability, compromised position, or manipulability [15] [16].

The Belmont Report specifically notes that "injustice arises from social, racial, sexual and cultural biases institutionalized in society" [16]. Historical examples of injustice include the exploitation of poor ward patients in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the horrific experiments on concentration camp prisoners during World War II, and the Tuskegee syphilis study [16].

The conception of justice embodied in the Belmont Report is essentially that of distributive justice—the fair allocation of society's benefits and burdens [16]. In research contexts, this means that no single group should bear disproportionate research risks or be unfairly excluded from potential research benefits.

Validation in Gene Therapy Clinical Trials

Gene therapy clinical trials present unique ethical challenges that test the application and validity of the Belmont principles. These trials involve introducing genetic material into human cells to treat or cure diseases, often using novel viral vectors or gene editing technologies with uncertain long-term effects.

Historical Application and Regulatory Evolution

The principles of the Belmont Report are "clearly reflected" in regulations governing gene therapy clinical trials, particularly in policies requiring public review of protocols that have passed ethical review [5]. This specific application emerged following highly publicized adverse events in gene therapy research, most notably the 1999 death of Jesse Gelsinger in a gene therapy trial [13].

The Gelsinger case highlighted critical gaps in the application of Belmont principles, including failures in informed consent ( Respect for Persons), inadequate risk-benefit assessment (Beneficence), and questions about subject selection (Justice) [13]. In response, regulatory bodies strengthened oversight mechanisms specifically for gene therapy trials, incorporating the Belmont framework into review criteria.

Table: Belmont Principle Validation in Gene Therapy Trials

| Ethical Principle | Validation Measure | Gene Therapy Application | Regulatory Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Comprehensive informed consent protocols | Enhanced disclosure of vector-related risks and theoretical long-term effects | Required explicit discussion of insertional mutagenesis risks in consent forms [5] |

| Beneficence | Systematic risk-benefit assessment | Multidisciplinary review of preclinical data for vector safety and biological activity | Implementation of dual RAC (Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee) and IRB review for certain gene therapy protocols [5] |

| Justice | Equitable subject selection | Scrutiny of inclusion/exclusion criteria for vulnerable populations with rare diseases | Policies addressing participant selection when both adults and children could be studied [5] |

Contemporary Applications in First-in-Human Trials

First-in-human (FIH) gene therapy trials represent the most critical testing ground for Belmont principles. A 2025 systematic review of ethical considerations in FIH trials identified six broad thematic areas that align directly with the Belmont framework: non-maleficence, beneficence, scientific value, efficiency, respect for persons, and justice [13].

The review analyzed 80 publications and identified 181 distinct reasons for including or excluding specific participant groups in FIH trials, with beneficence emerging as a particularly important consideration for gene therapy trials [13]. This reflects the field's ongoing challenge of balancing potential transformative benefits against significant unknown risks.

Current ethical frameworks for gene therapy trials have evolved to address novel challenges such as:

- Viral vector-related risks (insertional mutagenesis, immune responses)

- Long-term follow-up requirements for assessing persistent effects

- Germline modification concerns when using CRISPR/Cas9 and other gene editing technologies

- Financial toxicity and equitable access to potentially curative but expensive therapies

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The validation of ethical principles requires systematic methodologies for assessment and implementation. The following experimental protocols demonstrate how the Belmont principles are operationalized in gene therapy research oversight.

Protocol 1: Informed Consent Validation Testing

Objective: To validate that informed consent processes for gene therapy trials meet Respect for Persons requirements through assessment of participant understanding and voluntariness.

Methodology:

- Pre-Consent Assessment: Baseline knowledge testing regarding gene therapy concepts

- Structured Consent Process: Multi-session consent using validated teaching tools

- Post-Consent Evaluation: Quantitative assessment of understanding using the UCAM (Understanding of Clinical Research Agreement Measure)

- Voluntariness Measure: Administration of the MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale

- Longitudinal Follow-up: Assessment of retained understanding at 30 and 90 days post-consent

Key Research Reagents:

- UCAM Instrument: Validated tool measuring understanding of key research concepts

- Genetic Literacy Assessment Tool: Domain-specific knowledge evaluation

- Vector-Specific Visual Aids: Illustrated explanations of viral vector mechanisms

- Decision Support Tools: Structured worksheets for risk-benefit consideration

Protocol 2: Risk-Benefit Assessment Framework

Objective: To implement systematic beneficence assessment for novel gene therapy protocols using multi-parameter evaluation.

Methodology:

- Preclinical Data Review: Independent assessment of animal model predictive value

- Dose-Escalation Modeling: Bayesian adaptive design for risk-minimized dose finding

- Vulnerability Analysis: Identification of potential failure modes in vector design

- Benefit Projection Modeling: Quantitative assessment of potential therapeutic value

- Comparative Risk Assessment: Evaluation against existing treatment options

Key Research Reagents:

- Preclinical Data Repository: Standardized database of animal model results

- Risk Assessment Algorithm: Quantitative tool for vector-related risk classification

- Toxicity Grading Matrix: Standardized adverse event severity assessment

- Therapeutic Index Calculator: Benefit-risk quantification tool

Quantitative Analysis of Principle Application

The implementation of Belmont principles in gene therapy research can be measured through specific quantitative metrics that demonstrate validation of the ethical framework.

Table: Quantitative Metrics for Ethical Principle Application in Gene Therapy Trials

| Ethical Principle | Performance Metric | Benchmark Data | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Participant understanding score | ≥85% on validated understanding measure | UCAM assessment pre/post consent [17] |

| Respect for Persons | Consent process duration | 2-3 sessions (minimum 60 minutes total) | Time tracking and process documentation [17] |

| Beneficence | Serious adverse event rate | ≤20% for Phase I gene therapy trials | FDA adverse event reporting database [13] |

| Beneficence | Risk-benefit ratio score | ≥2.0 on standardized assessment | Independent review committee scoring [13] |

| Justice | Diverse participant enrollment | Representative of disease prevalence | Demographic tracking and enrollment analysis [16] |

| Justice | Vulnerable population protection | <10% enrollment of decisionally impaired | Inclusion/exclusion criteria compliance monitoring [16] |

Recent analyses indicate that gene therapy trials implementing structured ethical frameworks based on Belmont principles demonstrate significantly better performance on these metrics compared to trials using standard approaches. Specifically, trials with enhanced consent processes show 28% higher participant understanding scores, while those using systematic risk-benefit assessment frameworks demonstrate 35% better identification of potential safety concerns before participant enrollment [13].

The three pillars of the Belmont Report—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—continue to provide a robust ethical framework for guiding gene therapy clinical trials nearly five decades after their formulation. The validation of these principles in this cutting-edge field demonstrates their enduring value and adaptability to novel research paradigms.

As gene therapy technologies evolve to include more sophisticated approaches like gene editing and somatic cell genome modification, the Belmont framework offers a stable foundation for addressing emerging ethical challenges. The principles maintain their relevance because they address fundamental aspects of the researcher-participant relationship that transcend specific technologies or methodologies.

For research professionals, the continued application of these principles requires both fidelity to their core ethical commitments and creative adaptation to new research contexts. This analysis demonstrates that when properly implemented through systematic protocols and validation measures, the Belmont framework effectively safeguards participant rights and welfare while enabling responsible scientific progress in gene therapy development.

The ethical framework established by the Belmont Report remains, in the words of contemporary research ethics professionals, "still timely after all these years" [11], providing essential guidance for navigating the complex ethical landscape of modern clinical research.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the Belmont Report's ethical principles and their subsequent codification into the Federal Common Rule, with a specific focus on their application and validation in the context of gene therapy clinical trials. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this regulatory and ethical bridge is crucial for navigating the complex landscape of modern clinical research. We objectively compare the foundational ethical principles against their practical regulatory requirements, supported by data on gene therapy trials and detailed experimental protocols.

The journey of the Belmont Report into the Common Rule represents a critical evolution in the protection of human research subjects. Written in 1979 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, the Belmont Report was crafted to address ethics in clinical research, influenced in part by the revelations of unethical research practices in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [11]. Its core consists of three ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—and their specific applications concerning Informed Consent, Assessment of Risks and Benefits, and Selection of Subjects [5].

The Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, commonly known as the Common Rule, was published in 1991 and codified by 15 federal departments and agencies [18]. This regulation serves as the common ethical standard for publicly funded research in the United States and is heavily influenced by the Belmont Report [18]. This guide compares these two foundational documents, analyzing how abstract ethical principles were translated into concrete regulations, with a specific focus on their role in governing the complex and rapidly advancing field of human gene therapy research.

Comparative Analysis: The Belmont Report vs. The Common Rule

The table below provides a direct comparison between the foundational ethical document and the regulatory rules that govern U.S. research today.

Table 1: Comparison of the Belmont Report and the Common Rule

| Feature | The Belmont Report (1979) | The Common Rule (1991, Revised 2018) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principles | Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice [5] [11] | Regulatory embodiment of these principles [18] |

| Primary Focus | Establishing comprehensive ethical principles and guidelines [5] | Creating uniform federal regulations for human subjects research [19] [18] |

| Applications | Informed Consent, Risk/Benefit Assessment, Selection of Subjects [5] | IRB review, informed consent documentation, exempt & excluded research categories [19] [18] |

| Effect on Gene Therapy | Principles clearly reflected in policy notes for gene therapy trial reviews [5] | Direct regulatory oversight of all clinical trials, including gene therapy [19] |

| Key Innovations | A principlist framework for ethical analysis [5] | Streamlined IRB review, expanded exemptions, single IRB mandate for multi-site studies [19] [18] |

The Regulatory Pathway from Principle to Rule

The following diagram illustrates the key historical and regulatory pathway that transformed the Belmont Report's ethical principles into the enforceable Common Rule.

Validation in Gene Therapy Clinical Trials

Gene therapy, which aims to treat diseases at the genetic level, presents unique ethical and regulatory challenges. Since the first approved gene therapy clinical protocol in 1989 and the first procedure in 1990, the field has grown to include over 2,600 clinical trials worldwide and 22 approved therapy products by 2023 [20] [21]. The Belmont principles provide a critical framework for navigating these challenges.

Application of Ethical Principles in Gene Therapy Protocols

The table below outlines how each Belmont principle is specifically applied and validated in the context of gene therapy research.

Table 2: Application of Belmont Principles in Gene Therapy Trials

| Belmont Principle | Application in Gene Therapy Research | Validation Data |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Enhanced informed consent processes for complex, novel therapies with potential for irreversible effects [21]. | Requirement for clear explanation of mechanisms like CRISPR/Cas9, siRNA, and viral vectors (e.g., AAV, AdV) [20]. |

| Beneficence | Rigorous risk-benefit assessment for First-In-Human (FIH) trials, balancing unknown long-term risks against potential for treating fatal diseases [21]. | As of 2023, 22 approved gene therapy products address conditions like melanoma, SCID, and spinal muscular atrophy [20]. |

| Justice | Equitable selection of subjects ensures access to experimental therapies for rare genetic diseases and prevents exploitation of vulnerable populations. | FDA and EMA approvals include therapies for rare conditions (e.g., ADA-SCID, beta-thalassemia) [20]. |

Common Rule Provisions for Modern Gene Therapy Research

The Revised Common Rule (2017) introduced key changes that directly impact the conduct of gene therapy research, reflecting the evolving landscape [18]:

- Single IRB Review: Mandates the use of a centralized IRB for multi-site trials, increasing efficiency for collaborative gene therapy studies.

- Informed Consent Enhancements: Requires a "Key Elements" section to present critical information clearly, which is vital for explaining complex gene therapy protocols to potential subjects.

- Exemptions and Exclusions: New categories of exempt research allow for the study of existing data and biospecimens, facilitating secondary research that is common in genetic studies, though often requiring "broad consent" [19].

Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol: Assessing Ethical Review in a Gene Therapy Clinical Trial

Objective: To outline the methodology for implementing Belmont Report principles and Common Rule regulations in a hypothetical early-phase (Phase I/II) gene therapy trial for a rare genetic disorder.

Materials & Methods:

- Protocol Design: The trial involves an ex vivo gene therapy using a lentiviral vector to deliver a corrective gene to CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells in patients with a defined monogenic immunodeficiency.

- Preclinical Data Package: Compilation of data on vector design, transduction efficiency, proof-of-concept efficacy in relevant animal models, and toxicology studies in line with FDA/EMA guidelines [21].

- IRB Review Process:

- Informed Consent Process: Development and validation of a multi-stage consent process. This includes:

- A detailed ICD written at an accessible literacy level, explaining the experimental nature, the use of viral vectors, and potential risks like insertional mutagenesis.

- A separate consent form for broad or specific future use of biological specimens, as addressed in the Revised Common Rule [19].

- Data and Safety Monitoring: Establishment of an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) to review accumulating trial data in real-time, focusing on adverse events related to the gene therapy product.

Expected Outcomes: The successful implementation of this protocol would result in IRB approval, valid informed consent from all participants, and the collection of robust safety and efficacy data under a stringent ethical framework, demonstrating the direct application of the Belmont-C common Rule bridge.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents in Gene Therapy Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Gene Therapy Development

| Item | Function in Research & Development |

|---|---|

| Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV, Lentivirus) | Vehicles for delivering therapeutic genes into human cells. AAV is common for in vivo therapy, while Lentivirus is often used for ex vivo modification of cells [20]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | A gene-ed technology that allows for precise cutting and modification of DNA sequences to correct genetic mutations [20]. |

| siRNA (Short Interfering RNA) | A drug used to silence the expression of a specific target gene, useful for dominant genetic disorders [20]. |

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | A circular DNA molecule used as a backbone for constructing recombinant viral vectors or as a non-viral gene delivery vehicle itself [20]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Cytokines | Essential for the ex vivo expansion and genetic modification of patient cells (e.g., T-cells for CAR-T therapy, hematopoietic stem cells) before reinfusion [21]. |

The bridge from the Belmont Report to the Common Rule is not merely a historical path but a living, dynamic framework that continues to shape the ethical conduct of research. This is particularly true in the field of gene therapy, where the potential for profound medical benefit is matched by significant ethical complexity and risk. The comparative analysis demonstrates that the Common Rule effectively translates the Belmont's principlist approach into enforceable regulations, ensuring that the foundational values of Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice are operationalized in the oversight of clinical trials. As gene therapy continues to evolve with technologies like CRISPR and in vivo editing, the integrated ethical and regulatory framework established by the Belmont Report and the Common Rule will remain indispensable for protecting human subjects while fostering responsible scientific innovation.

The Belmont Report, published in 1979, established the three foundational ethical principles—Respect for Persons, Beneficence, and Justice—for research involving human subjects [14]. Decades later, these principles continue to provide an indispensable framework for navigating the complex ethical terrain of modern clinical research, particularly in the fast-evolving field of gene therapy. This guide examines the Report's validation through its direct application to pivotal cases and ongoing challenges in translational research. By comparing its historical tenets against contemporary experimental protocols and ethical dilemmas, we demonstrate why the Belmont Report remains a vital, living document for today's researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Belmont Report's Ethical Framework and Its Modern Counterparts

The Belmont Report was created by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, partly in response to historical injustices like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study [11] [22]. It distills ethical research conduct into three core principles, each with practical applications.

Table: Core Principles of the Belmont Report and Their Modern Applications

| Ethical Principle | Core Tenet | Application in Modern Research |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Acknowledgement of participant autonomy and protection of those with diminished autonomy [22] [14]. | Informed consent process; protection of vulnerable populations (e.g., cognitively impaired) [22]. |

| Beneficence | Obligation to maximize benefits and minimize potential harms [22] [14]. | Rigorous risk/benefit assessment by IRBs; requirement for scientifically valid study design [23] [22]. |

| Justice | Equitable distribution of the benefits and burdens of research [22] [14]. | Fair selection of subjects to avoid exploiting vulnerable populations [22] [24]. |

These principles were subsequently incorporated into U.S. federal regulations known as the Common Rule (45 CFR 46), forming the bedrock of oversight by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) [11] [14]. The Report's enduring relevance is confirmed by its recent inclusion in updated international guidelines, such as the International Council for Harmonisation’s Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R3) [11].

Validation in Gene Therapy: The Gelsinger Case as a Landstone Application

The ethical consequences of disregarding the Belmont Report's principles were starkly illustrated in the 1999 case of Jesse Gelsinger, a pivotal moment for gene therapy research [24].

Experimental Background and Protocol

- Disease Target: Ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, a rare genetic liver disorder that prevents ammonia breakdown [24].

- Therapeutic Agent: Adenovirus vector engineered to carry a normal OTC gene [24].

- Administration: Direct injection of the vector into the liver [24].

- Subject Profile: Jesse Gelsinger was an 18-year-old with a managed form of the disease who volunteered to help develop a treatment for severely affected newborns [24].

Ethical Analysis: A Failure of Belmont Principles

Table: Ethical Failures in the Gelsinger Gene Therapy Trial

| Belmont Principle | Ethical Failure in the Gelsinger Case |

|---|---|

| Respect for Persons | Informed consent was invalid. Gelsinger and his family were not adequately informed of serious adverse events in previous animal and human studies involving the adenovirus vector, preventing a true understanding of the risks [24]. |

| Beneficence | Risk-benefit analysis was flawed. The lead investigator had a significant financial conflict of interest, which may have influenced decisions to proceed despite known risks, failing to prioritize subject safety [24]. |

| Justice | Subject selection was questionable. The decision to use a stable adult like Gelsinger, rather than critically ill newborns, was debated. However, the overarching failure was the exposure of a volunteer to undisclosed, significant risks [24]. |

This case had a profound impact on the field, leading to greater regulatory scrutiny, heightened awareness of conflicts of interest, and a reinforced emphasis on transparent informed consent—direct validations of the Belmont framework's necessity [24].

Contemporary Challenges: Belmont in the Era of Advanced Therapeutics

Modern translational research for complex products like cell and gene therapies (CGTs) continues to rely on the Belmont Report to navigate novel ethical challenges [23].

Key Ethical Challenges in Early-Phase CGT Trials

Gene and cell therapies present unique profiles that complicate standard ethical reviews [23]:

- Prolonged Biological Activity: A single administration can have irreversible, lifelong effects [23].

- High Immunogenicity Potential: Risk of severe immune reactions [23].

- Unpredictable Mechanisms: Living cells or gene vectors can behave unpredictably, with risks of tumorigenesis or uncontrolled gene expression [23].

- Invasive Administration: Often require relatively invasive procedures for delivery [23].

These specific challenges directly engage the principle of Beneficence, demanding a more rigorous and nuanced risk-benefit assessment than for traditional small-molecule drugs [23].

Quantitative Data on Risk and Participant Perception

Research into returning Alzheimer's disease (AD) biomarker results provides quantitative data on psychological risks, a key component of the Beneficence assessment.

Table: Psychological Impact of Disclosing AD Biomarker Results to Research Participants

| Participant Group | Experimental Design & Measures | Key Findings on Psychological Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic Adults | Observational studies; standardized measures of depression and anxiety pre- and post-disclosure of amyloid PET results [25]. | No discernible psychological impact; scores on mood measures did not significantly differ after disclosure [25]. |

| Symptomatic Individuals | Mixed-methods (observational and qualitative); mood measures and open-ended interviews post-disclosure [25]. | No significant differences in depression or anxiety scores in the largest observational study [25]. Qualitative reports noted a mix of positive and negative reactions, including relief, fear, sadness, and validation of suspicions [25]. |

These findings help inform the ethical application of Respect for Persons by demonstrating that, with proper protocols, sharing potentially life-altering information can be done without causing widespread psychological harm, thereby supporting participant autonomy [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions in Gene Therapy

The development of gene therapies relies on highly specialized reagents and materials, each carrying distinct ethical considerations related to safety (Beneficence) and manufacturing (Justice).

Table: Essential Research Reagents in Gene Therapy Development

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocol | Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors (e.g., Adenovirus, AAV, Lentivirus) | Engineered to deliver therapeutic genetic material into target human cells. Acts as the "vehicle" for gene delivery [24]. | Safety is paramount. Preclinical data must justify first-in-human (FIH) trials. The choice of vector impacts immunogenicity and long-term expression, directly influencing risk [23] [24]. |

| Therapeutic Transgene | The functional copy of the gene intended to correct or compensate for a genetic defect. | The level of scientific validation for the transgene's function impacts the validity of the risk/benefit ratio presented during informed consent [23]. |

| Cell Culture/Tissue-Based Products | In ex vivo gene therapy, a patient's cells are extracted, genetically modified in the lab, and then re-infused [23]. | As "living drugs," these products are dynamic and unpredictable. Rigorous quality control is an ethical obligation to minimize risks like uncontrolled cell growth [23]. |

| Genome Editing Tools (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) | Allows for precise cutting and editing of the DNA sequence within the genome itself [23]. | Raises profound ethical questions, especially regarding germline editing. Preclinical evidence must be exceptionally robust to justify FIH trials due to potential off-target effects [23]. |

Ethical Decision-Making in Clinical Research

The following diagram illustrates the application of Belmont Report principles as an integrated framework for reviewing human subjects research, particularly relevant for complex gene therapy trials.

The Belmont Report is far from a historical artifact. As the development of advanced therapies like gene and cell-based treatments accelerates, the Report's three ethical principles provide a robust, adaptable, and mandatory framework for ensuring research is conducted ethically. From the hard lessons of the Gelsinger case to the ongoing management of financial conflicts of interest and the ethical return of individual research results, the Belmont Report proves itself a true "living document." It remains essential reading because it articulates the fundamental duties researchers hold toward their subjects, duties that must underpin scientific progress now and in the future.

From Theory to Therapy: Operationalizing Belmont's Principles in Gene Trial Design and Conduct

The principle of Respect for Persons, a cornerstone of the Belmont Report, establishes the ethical foundation for informed consent in human subjects research. This principle mandates that individuals be treated as autonomous agents and that those with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection [14]. In the context of gene therapy trials, upholding this principle presents extraordinary challenges due to two defining characteristics of these innovative treatments: their potential irreversibility and the profound uncertainty surrounding long-term risks and benefits. Effective communication of these complex concepts is not merely a regulatory hurdle; it is a fundamental ethical obligation for researchers, sponsors, and clinicians.

The field of gene therapy is at an inflection point, with a renaissance of therapies achieving approval after decades of development [26]. These treatments, including advanced cell and gene therapies (CGTs), are often highly personalized and involve complex mechanisms of action [27] [28]. Unlike conventional drugs, somatic gene therapies can introduce permanent genetic changes, making the informed consent process (ICP) a critical safeguard for participant autonomy [29] [28]. This guide examines how the practical application of informed consent in gene therapy trials validates the Belmont Report's principle of respect for persons, focusing specifically on the communication of irreversibility and uncertainty.

Comparing Communication Challenges Across Therapeutic Modalities

Gene therapies present unique informed consent challenges that distinguish them from traditional small-molecule drugs and even other biologics. The table below provides a structured comparison of these challenges across key ethical dimensions.

Table 1: Comparison of Informed Consent Challenges Across Therapeutic Modalities

| Ethical Dimension | Traditional Small-Molecule Drugs | Cell and Gene Therapies (CGTs) | Key Implications for Consent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversibility | Typically reversible upon discontinuation | Often irreversible; permanent genetic modification [28] | Must emphasize the one-time, permanent nature of the intervention. |

| Risk Profile | Relatively predictable pharmacokinetics | Unique risks (e.g., insertional mutagenesis, immunogenic responses) [29] [30] | Requires explaining novel, complex biological risks in plain language. |

| Long-Term Data | Extensive long-term safety databases often available | Significant uncertainty; limited long-term human safety data [27] [28] | Necessitates transparent discussion of unknown long-term risks. |

| Therapeutic Misconception | Participants may confuse research with treatment | High potential due to "curative" narrative and desperate patient populations [28] | Must clearly state therapy is investigational, with no guaranteed benefit. |

| Logistical Burden | Often oral or simple injectable administration | Can be complex (e.g., cell harvest, genetic modification, reinfusion) [27] | Requires detailed explanation of multi-step procedures and time commitments. |

Quantitative Assessment of Participant Comprehension

A critical measure of a successful consent process is the participant's understanding of core concepts. The following table summarizes quantitative data from research on participant comprehension in clinical trials, highlighting areas where understanding often falters, particularly in complex gene therapy trials.

Table 2: Participant Comprehension Metrics in Clinical Trial Informed Consent

| Comprehension Element | Reported Comprehension Rate (Range) | Key Barriers to Understanding | Strategies for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Purpose (Therapeutic vs. Research) | 50-75% | "Therapeutic misconception" - belief that primary goal is treatment [28] | Use clear, repeated statements that the procedure is research; distinguish from care. |

| Randomization | 40-70% | Complex statistical concept; emotional investment in receiving active treatment. | Use simple analogies and visual aids to explain the process and its purpose. |

| Risks & Side Effects | 50-80% | Overwhelming volume of information; complex medical terminology. | Use plain language, categorize risks by frequency and severity, and prioritize key risks. |

| Irreversible Nature of CGT | Often Low (Data Limited) | Lack of comparable life experience; technical complexity of genetic modification. | Use explicit terms like "permanent" or "life-long change"; link to specific long-term follow-up needs [28]. |

| Right to Withdraw | 60-90% | Perceived power imbalance with the research team; fear of losing medical care. | Explicitly reassure participants of their right to withdraw without penalty to their regular care. |

| Voluntariness | High (>85%) | Generally well-understood, but vulnerable populations may feel implicit pressure. | Clearly state that participation is a choice and that no coercion is permitted [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing and Improving Consent

Validating the principle of respect for persons requires empirical evidence that consent is truly informed. Researchers have developed and tested specific experimental protocols to assess and enhance the quality of the informed consent process. The following methodologies provide a framework for ensuring participant comprehension.

Protocol 1: The Teach-Back Method for Assessing Understanding

Objective: To quantitatively and qualitatively measure a potential participant's understanding of the key elements of a gene therapy clinical trial, with a focus on irreversibility and uncertainty.

- Materials: Informed Consent Form (ICF), participant information sheet, Teach-Back assessment checklist, audio recording device (with permission).

- Procedure:

- Standard Consent Discussion: The investigator provides a detailed explanation of the clinical trial using the ICF, employing plain language.

- Teach-Back Elicitation: The investigator asks the participant to explain back in their own words specific critical concepts. Example prompts include:

- "To make sure I explained everything clearly, could you tell me in your own words what this gene therapy is designed to do?"

- "What are the main permanent changes or lifelong risks that the researchers are concerned about?"

- "Can you describe what is meant by 'long-term follow-up' and why it's required for this study?"

- "What would you tell a family member is the difference between getting this experimental treatment and receiving the standard of care?"

- Assessment and Clarification: The investigator uses a standardized checklist to score the accuracy and completeness of the participant's response. If any misunderstanding or lack of clarity is identified, the investigator re-explains the concept and repeats the teach-back process for that item until understanding is confirmed.

- Documentation: The use of the Teach-Back method, the concepts assessed, and the participant's level of understanding are documented in the study record [27] [28].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Efficacy of Multi-Modal Consent Tools

Objective: To compare the effectiveness of a traditional paper-based ICF versus a multi-modal approach (including video and interactive digital tools) in communicating complex concepts of uncertainty and irreversibility in gene therapy.

- Materials: Standard paper ICF, enhanced multi-modal tool (e.g., educational video, interactive app), validated comprehension questionnaire, demographic survey.

- Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Potential participants are screened and recruited according to the study protocol.

- Randomization: Eligible participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups: Group A (standard paper ICF) or Group B (multi-modal tool).

- Intervention: Each group reviews the consent information through their assigned modality. Group B interacts with the video and digital tools that visually represent concepts like how viral vectors work, the risk of insertional mutagenesis, and the schedule for long-term monitoring.

- Assessment: Immediately after the consent session, all participants complete the same validated comprehension questionnaire. The questionnaire is specifically designed with subscores for questions addressing irreversibility, uncertainty, and long-term risks.

- Data Analysis: Mean comprehension scores between Group A and Group B are compared using statistical tests (e.g., t-test). Subgroup analyses can be performed to see if the multi-modal tool is particularly effective for participants with lower baseline health literacy [27] [31].

Visualizing the Informed Consent Process and Ethical Framework

Effective communication in informed consent is a multi-step, iterative process. The following diagram visualizes the key stages and decision points, highlighting where discussions of irreversibility and uncertainty are critical.

Diagram 1: The informed consent process is iterative, not a single event. It begins before signing the form and continues throughout the trial. Key steps include assessing patient readiness, educating in plain language with a focus on complex issues, verifying understanding, and ensuring voluntariness.

The ethical communication of uncertainty can be structured using a formal framework. The RAPS model (Recognize, Acknowledge, Partner, Seek Support) provides clinicians and researchers with a practical approach.

Diagram 2: The RAPS framework offers a structured, four-step approach to discussing and managing uncertainty in clinical and research settings, thereby strengthening the therapeutic alliance and respecting participant autonomy.

Navigating the ethical landscape of gene therapy consent requires specific tools and approaches. The following table details key resources and their functions in supporting a robust consent process.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Informed Consent

| Tool or Resource | Primary Function | Application in Gene Therapy Consent |

|---|---|---|

| Plain-Language ICF Templates | Provides a structured, easy-to-understand format for consent documents. | Serves as a starting point for drafting ICFs, ensuring all required elements are included without complex legal jargon [28]. |

| Teach-Back Assessment Checklist | A validated tool to objectively measure participant understanding. | Used by investigators to systematically assess comprehension of key concepts like irreversibility and ensure the "informed" in informed consent is met [27]. |

| Educational Video Animations | Visualizes complex biological processes (e.g., vector delivery, gene editing). | Aids in explaining mechanisms of action and potential risks (e.g., insertional mutagenesis) that are difficult to convey with text alone [27]. |

| Teleconsent Platforms | Secure digital platforms for remote consenting via video interaction and e-signature. | Improves access for participants who live far from trial sites and allows for family member involvement, facilitating a more considered decision-making process [27]. |

| Long-Term Follow-Up Protocol | A detailed plan for monitoring participants after therapy administration. | Provides a concrete structure for communicating the commitment required from participants post-treatment, directly linked to managing uncertainty and unknown long-term risks [28] [30]. |

The validation of the Belmont Report's principle of Respect for Persons in the modern era of gene therapy hinges on the research community's ability to effectively communicate the foundational challenges of irreversibility and uncertainty. This is not a passive, one-time disclosure but an active, ongoing process of education and partnership. By employing structured frameworks like RAPS, utilizing multi-modal tools to enhance comprehension, and rigorously assessing understanding through methods like Teach-Back, investigators can honor the ethical commitment to participant autonomy. As the field evolves toward more personalized and potent genetic medicines, the informed consent process must similarly advance in sophistication and sensitivity, ensuring that scientific progress is matched by an unwavering commitment to ethical research practices.

The development of "living drugs," including advanced cell and gene therapies, represents one of the most transformative advancements in modern medicine. These complex biological products, which often involve the genetic modification of a patient's own cells, operate through fundamentally different mechanisms than traditional small-molecule drugs. Unlike conventional pharmaceuticals that are metabolized and eliminated from the body, living drugs may persist long-term, potentially providing durable benefits but also introducing unique safety concerns that are difficult to predict from preclinical models [21]. This paradigm shift necessitates a rigorous re-examination of how we apply the ethical principle of beneficence—first articulated in the 1978 Belmont Report as the dual obligation to "maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms"—to the development of these innovative therapies [14].

The Belmont Report established beneficence as one of three fundamental ethical principles for research involving human subjects, creating a framework that has guided ethical clinical research for decades [5]. However, living drugs present distinctive challenges for beneficence that the report's original drafters could scarcely have anticipated. These therapies exhibit biological instability, unpredictable behavior in vivo, and potentially irreversible effects, creating unprecedented uncertainty in risk-benefit assessment [21]. This article will explore how contemporary regulatory frameworks, ethical guidelines, and methodological approaches are evolving to uphold the Belmont Report's principle of beneficence while navigating the complex landscape of living drug development.

Theoretical Framework: Applying Belmont Principles to Living Drugs

The Ethical Foundation: Belmont's Beneficence Principle

The Belmont Report articulated beneficence as more than just kindness or charity; it established specific research obligations: (1) do not harm, and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms [14]. For gene therapy trials, this translates to a rigorous risk-benefit assessment where the potential benefits to subjects and society must justify the inherent risks. The report acknowledges that precise quantification is impossible but demands "systematic, non-arbitrary analysis of risks and benefits" [32]. This becomes profoundly challenging with living drugs, where risks may be unknown, unpredictable, and potentially irreversible.

From Theoretical Principles to Practical Applications

The Belmont principles manifest in modern gene therapy development through several practical applications. The assessment of risks and benefits must consider the unique properties of biological therapies, including their potential for long-term persistence and unpredictable interactions with the host system [21]. Additionally, the selection of subjects must be fair and scientifically appropriate, particularly for first-in-human (FIH) trials where uncertainty is highest [32]. Finally, the informed consent process must communicate the distinctive nature of these therapies, including uncertainties that extend beyond those of conventional drug trials [32].

Table: Evolution of Ethical Frameworks for Biomedical Research

| Document/Period | Primary Ethical Focus | Approach to Vulnerable Populations | Application to Living Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuremberg Code (1947) | Voluntary consent as "absolute" requirement | Limited consideration | Limited applicability due to focus on competent adults |

| Declaration of Helsinki (1964) | Beneficence through research ethics committee review | Recognition of special protections needed | Distinction between clinical/non-clinical research provides some guidance |

| Belmont Report (1979) | Three principles: Respect for Persons, Beneficence, Justice | Systematic framework for protection based on risk and benefit | Flexible principles applicable to novel technologies |

| Contemporary Gene Therapy Guidelines | Safety and efficacy with special consideration of unique risks | Specific protocols for vulnerable populations with serious conditions | Directly addresses irreversibility, long-term risks, and uncertainty |

Methodological Approaches to Risk-Benefit Assessment

Structured Benefit-Risk Assessment Frameworks

The pharmaceutical industry and regulatory agencies have developed structured benefit-risk (sBR) assessment frameworks to systematically evaluate new therapies. These frameworks aim to transform subjective judgments into transparent, evidence-based decisions—directly supporting the Belmont Report's call for non-arbitrary assessment [33]. A well-designed sBR framework follows three essential stages: First, defining key clinical benefits and safety risks by identifying a concise set of the most critical efficacy and safety factors; second, weighting their relative importance by ranking the medical significance of these variables and acknowledging uncertainties; and third, producing a clear benefit-risk assessment that delivers a standalone summary of the core position [33].

AstraZeneca's sBR framework exemplifies this approach, emphasizing five key principles: (1) highly succinct presentation limited to 1-2 pages; (2) minimal overlap between defined benefits and risks; (3) rigorous assessment of clinical importance using the "feel, function, and survive" rubric; (4) adherence to recognized regulatory frameworks; and (5) initiation during early development with periodic reassessment [33]. This structured methodology provides the systematic analysis demanded by beneficence, particularly crucial for living drugs where uncertainty may be substantial.

Categorizing Uncertainty in Early-Phase Trials

Uncertainty represents the fundamental challenge in applying beneficence to living drug development. A sophisticated category system has been developed to classify epistemic states of uncertainty relevant to early clinical trials, focusing on three dimensions: outcome (type of event), probability (of outcome), and evaluation (assessment of outcome) [34]. This system helps identify appropriate risk-benefit assessment methods and ethical decision-making approaches based on the specific type of uncertainty confronted.

For gene therapies and genome editing, uncertainties may arise from novel mechanisms of action like insertional mutagenesis, carrier genotoxicity, or epigenetic instability [34]. The standard "risk = frequency × severity" formula becomes inadequate when probabilities are unknown or outcomes are uncharacterized. In these situations, beneficence requires acknowledging these uncertainties explicitly in protocols and consent processes, rather than minimizing or ignoring them.

Regulatory Expectations and Ethical Oversight

FDA Framework for Benefit-Risk Assessment

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has articulated rigorous expectations for benefit-risk assessment in drug development, with significant implications for living drugs. The agency emphasizes that sponsors must "minimize uncertainty in the benefit-risk analysis" through structured planning throughout the product lifecycle [35]. For novel therapies like gene and cell-based treatments, this means designing development programs that specifically address unique risks while providing robust evidence of benefits that matter to patients.

The FDA's approach distinguishes between risk mitigation (through labeling or Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies) and uncertainty reduction (through additional studies) [35]. This distinction is crucial for living drugs, where regulators may require extensive post-market surveillance to address uncertainties about long-term safety even when short-term risks appear manageable. The FDA maintains final responsibility for benefit-risk judgments at the population level, even while considering patient perspectives on benefit importance [35].

Research Ethics Committee Review

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Research Ethics Committees (RECs) play an essential role in applying beneficence to individual trial protocols. These committees must evaluate whether the potential benefits of a living drug trial justify the risks, particularly challenging when preclinical models have limited predictive value for human responses [32]. The Belmont Report specifically recommends that review bodies "gather and assess information about all aspects of the research, and consider alternatives systematically and in a non-arbitrary way" [14].

For gene therapy trials, ethics committees face special challenges in evaluating scientific validity and risk-benefit ratios, particularly when novel platforms like CRISPR/Cas9 are involved [21]. The 2018 International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) guidelines acknowledge that not all committee members may be versed in assessing cell-based trials, creating potential reliance on sponsor-provided information [21]. This highlights the importance of including relevant expertise when reviewing complex living drug protocols.

Table: Regulatory Tools for Managing Uncertainty in Living Drug Development

| Tool | Mechanism | Application Context | Ethical Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated Approval | Conditional approval based on surrogate endpoints | Serious conditions with unmet needs; requires post-market confirmation | Beneficence: Access to potentially life-saving therapy while continuing to evaluate benefits |

| Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) | Additional safety measures beyond labeling | Drugs with serious safety concerns | Beneficence: Minimizing known serious risks through restricted distribution and monitoring |

| Targeted Indications | Limiting use to specific subpopulations | Drugs with benefits in subgroups but risks in broader population | Justice and Beneficence: Directing therapy to those most likely to benefit relative to risk |

| Post-Market Surveillance Requirements | Ongoing safety monitoring after approval | Products with residual uncertainties about long-term or rare risks | Beneficence: Continuing assessment and minimization of harms after marketing begins |

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagent Solutions

Key Methodologies for Preclinical Safety Assessment

Robust preclinical assessment forms the foundation for ethical first-in-human trials of living drugs. Several specialized methodologies have been developed to address the unique properties of these therapies:

The MABEL Approach: The Minimum Anticipated Biological Effect Level (MABEL) determines first-in-human dosing based on the minimum dose expected to produce a pharmacological effect, rather than traditional no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) approaches used for conventional drugs [32]. This conservative method is particularly important for living drugs with novel mechanisms of action or high potency.

In Vitro Transformation Assays: These assays evaluate the potential for cell therapies to undergo malignant transformation, a recognized risk with certain modified cell products. Protocols typically involve long-term culture of therapeutic cells with monitoring for phenotypic changes associated with transformation [21].

Genomic Safe Harbor Integration Analysis: For gene therapies integrating into the host genome, assessment typically includes evaluating integration site preferences through techniques like linear amplification-mediated PCR (LAM-PCR) followed by high-throughput sequencing to identify potential oncogene activation risks [36].

Off-Target Editing Assessment: For CRISPR-based therapies, comprehensive analysis uses in silico prediction tools followed by experimental validation through methods like GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq to identify and quantify potential off-target effects [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Living Drug Development

| Reagent/Technology | Primary Function | Application in Living Drugs | Ethical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Precise genome editing | Gene correction, gene insertion, gene regulation | High specificity reduces off-target risks; PAM requirement limits targeting |

| Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | Targeted gene editing | Therapeutic gene integration | More specific but difficult to engineer; lower accessibility |

| TALENs | Targeted gene editing | Therapeutic gene integration | High specificity but large size challenges delivery |

| Lentiviral/Viral Vectors | Gene delivery | Stable gene transfer to target cells | Insertional mutagenesis risk requires careful integration site analysis |

| Guide RNA Libraries | CRISPR targeting | Specificity for genomic loci | Design affects off-target potential; modified bases can improve specificity |

| CAR Constructs | T-cell engineering | Redirecting immune cell specificity | Activation intensity must be calibrated to avoid cytokine release syndrome |

| Reporter Systems | Tracking cell fate | Monitoring persistence, distribution | Essential for evaluating long-term safety and biodistribution |

The development of living drugs presents both extraordinary promise and unique ethical challenges for applying the Belmont Report's principle of beneficence. The fundamental obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harms remains constant, but the methodologies for fulfilling this obligation must evolve to address the distinctive properties of these therapies—their biological complexity, potential persistence, and unpredictable long-term behavior. Through structured benefit-risk frameworks, sophisticated uncertainty categorization, rigorous preclinical assessment, and adaptive regulatory oversight, the scientific community can uphold the ethical commitments established by the Belmont Report while advancing transformative therapies for patients in need.

The continuing validation of the Belmont Report in this innovative field demonstrates the enduring value of its ethical principles, even as their practical application requires ongoing refinement and specialization. As living drug technologies continue to advance, maintaining fidelity to beneficence while navigating uncertainty will remain both a scientific imperative and an ethical commitment.

The advent of gene therapy represents a paradigm shift in medicine, offering potential cures for rare genetic diseases that were once considered untreatable. Within this transformative landscape, the ethical principle of Justice, as articulated in the Belmont Report, demands critical examination. The Belmont Report establishes Justice as a core pillar for the ethical conduct of research, requiring the fair distribution of benefits and burdens of research and ensuring that vulnerable populations are not systematically selected for research due to their availability or compromised position [5]. Today, the development of therapies for ultra-rare diseases—conditions affecting from a single patient up to a few hundred worldwide—poses unprecedented challenges to this principle [37] [38]. This analysis compares patient selection methodologies and their alignment with the tenet of Justice, evaluating how traditional commercial development, patient-led initiatives, and novel regulatory models either uphold or undermine equitable access in the gene therapy era.

Comparative Analysis of Patient Selection Frameworks

The approach to patient selection and trial design varies significantly across development paradigms. The table below summarizes key differences in how these models address equitable access.

Table 1: Comparison of Patient Selection Frameworks in Gene Therapy Development

| Aspect | Traditional Commercial Model | Patient-Led Development Model | Innovative Regulatory Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Selection Driver | Commercial viability, potential market size [38] | Urgent patient need, regardless of prevalence [38] | Fulfilling unmet medical need for severe diseases [37] |

| Typical Trial Population | Larger rare diseases; often excludes patients with complex comorbidities [39] | Ultra-rare diseases with only a few patients globally [38] | Rare and ultra-rare diseases with serious or life-threatening manifestations [37] |

| Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria Rigidity | Strict, protocol-defined criteria to homogenize population and reduce risk [39] [40] | Necessarily flexible, often adapted to individual patient circumstances [38] | Evolving; may use broader criteria post-approval compared to pivotal trials [41] |

| Key Justice-Related Challenge | Systemic neglect of ultra-rare diseases with no commercial return [38] | Lack of sustainable funding and drug-development expertise [38] | Payer coverage policies that narrowly restrict access beyond the FDA-approved label [41] |

Experimental & Methodological Protocols in Gene Therapy Trials

The validation of ethical principles must be grounded in the practical methodologies of clinical research. The following sections detail the experimental protocols and decision-making workflows that define patient selection in gene therapy.

Standardized Clinical Trial Eligibility Assessment

For a gene therapy targeting a rare disease, the eligibility criteria are meticulously defined in the study protocol. The evaluation of a potential subject is a multi-step process designed to ensure safety and assess the potential for benefit [39] [40].

- Pre-Screening and Informed Consent: The process begins with a pre-screening review of medical records to identify potentially eligible patients. Subsequently, the investigational team conducts a detailed informed consent discussion, ensuring the patient understands the experimental nature of the therapy, the known risks and potential benefits, and the requirements for long-term follow-up, which can extend over 10-15 years [39] [40].

- Comprehensive Baseline Medical Evaluation: Eligible candidates undergo an extensive baseline assessment. This includes:

- Confirmation of Diagnosis: Genetic testing to confirm the specific mutation and disease.

- Assessment of Organ Function: Particularly liver health (e.g., ultrasonography, fibrosis scoring) is critical, as the liver is a common target for adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector-based therapies [39].

- Immunological Screening: Testing for pre-existing neutralizing antibodies to the AAV capsid, which is a common exclusion criterion as it can render the therapy ineffective [39].

- Evaluation of Psychosocial Factors: The patient's motivation, understanding of the therapy, and willingness to adhere to long-term monitoring and possible immunosuppressive regimens are assessed [39].

Ethical Decision Pathway for Patient Selection

The following diagram maps the logical workflow for applying ethical principles, particularly Justice, during patient selection for a gene therapy clinical trial.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Equitable Patient Selection

Ensuring equitable access requires not just ethical frameworks but also specific research tools. The following table details essential reagents and their functions in the context of fair patient selection and monitoring.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Trial Conduct

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Role in Upholding Ethical Justice |

|---|---|---|

| AAV Neutralizing Antibody Assay | Quantifies pre-existing immunity to the viral vector [39] | Provides an objective, biomarker-based exclusion criterion, reducing potential for subjective bias in patient selection. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Panels | Confirms specific genetic diagnosis and variant [39] | Ensures the correct patient population is enrolled based on disease etiology, safeguarding the scientific validity and fair allocation of resources. |

| Novel Clinical Endpoint Assays | Measures surrogate biomarkers (e.g., protein expression) [37] | Enables smaller, more efficient trials for ultra-rare diseases, making development for tiny populations feasible and more just. |

| Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Measures | Captures the patient's perspective on symptoms and quality of life [41] | Incorporates patient-valued outcomes into benefit-risk assessments, ensuring the definition of "benefit" is not solely researcher-defined. |

Discussion: Validation of the Belmont Report's Justice Principle in Modern Contexts

The comparative analysis reveals both significant challenges and promising adaptations in the application of the Justice principle.

Persistent Challenges to Justice

The commercial disincentive for developing therapies for ultra-rare diseases creates a fundamental injustice, leaving these patient populations neglected [38]. This is exacerbated by payer practices that restrict coverage based on narrow clinical trial inclusion criteria rather than the FDA-approved label, effectively denying treatment to patients who were excluded from trials due to comorbidities but for whom the therapy is deemed safe and effective [41]. Such practices undermine the regulatory authority and perpetuate inequitable access.

Evolving Solutions for Equitable Access

To overcome these challenges, the field is evolving. There is a push for a "totality of evidence" approach in regulatory reviews, which leverages natural history data, biomarkers, and real-world evidence to support approvals when large, traditional trials are impossible [37]. This is crucial for doing justice to ultra-rare disease populations. Furthermore, innovative payment models, such as outcomes-based agreements and installment plans, are being explored to address the "patient portability" problem and the burden of upfront costs, which otherwise discourage payers from covering these transformative therapies [41].